ABSTRACT

This critical review paper expands on the meaning of place. It opens a new narrative on how the geographic concept of place is conceptualized in smallholder farmers and climate change adaptation literature in Sub-Saharan Africa. The review suggested that place is not only the ‘where’ of a location but a location geographically connected and interdependent to illustrate how smallholder farmers’ experiences in adapting to climate shocks interact with global efforts such as improving food security, eliminating poverty and building sustainable rural livelihood. Through the various climate change adaptation strategies exhibited by different farmer groups, the paper demonstrated that people in places have the agency to make choices that control their destinies irrespective of whatever global force overwhelms them. The paper argues sense of place expressed through ecological place meaning shapes people’s intuition, beliefs, actions and experiences as illustrated by smallholders’ perception of the determinant and barriers to effective adaptation strategies. The ecological place meaning also influences the ‘glocalization’ of climate impact on agroecological-based livelihoods at different locations and how maladaptive outcomes are perceived. Place gives people identity by (re)shaping actions and experiences and vice versa. There is an undeviating relationship between power, place and people’s experience. Further exploration of the relationship between lifeworld experiences, people, and power is central in understanding the meaning of place in smallholder farmers and climate change interaction.

1. Introduction

Adaptation to climate change is not a new phenomenon to smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa (hereafter SSA) (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2018; Dixon & Stringer, Citation2015). While research on climate adaptation is extensive, further exploration of the topic within rapidly changing climatic conditions is echoed by academics and practitioners alike. According to the IPCC (Citation2014) report, extreme weather variations such as droughts, floods and storms will pose significant challenges to the agriculture sector in SSA (Adger et al., Citation2003; Niang et al., Citation2014). The last two decades have seen a growing number of literature produced from research to further explore the topic within rapidly changing climatic conditions, mostly how farmers practice place-based adaptation strategies to mitigate against climate stress on their farm-livelihood. This paper is a critical review of smallholder farmers and climate change adaptation literature to understand how the geographic concept ‘place’ is conceptualized within the broad theme; smallholder farmers and climate change adaptation.

The paper is divided into six sections, and these are;

background context on place and smallholder agriculture in SSA;

globalization of places to demonstrate the global implication of climate change impact on SSA rural farmers;

smallholder farmers’ place-based adaptation strategies to climate shocks;

Sense of place and determinant of smallholders’ adaptation strategies and barriers to effective adaption to climate shocks;

place sustainability and maladaptation outcome of adaptation strategies; and

the key argument that unveils further opportunity to explore the concept of place with people and power.

The conclusion highlights how the geographic concept of place was used in the climate change adaption literature. Through this critical review work, the paper expands on the meaning of place in geography by opening a new narrative of how the geographic concept of place is conceptualized in smallholder farmers and climate change adaptation experiences in SSA to guide effective climate change adaptation practices for efficiency.

2. Background context

2.1 Geographic concept of place

Place is an essential concept in geography, which has gained much attention from both physical and human geographers. However, place is and meant different things in both subfields of geography and other disciplines (Gregory, Citation2009). Both subfields of geography believe in place – a particular part of space where there is an interaction between organisms and their environment (Castree, Citation2009; Gregory, Citation2009). Scholars like Relph (Citation1976, p. 29) note, ‘places are sensed in a chiaroscuro of setting, landscape, ritual, routine, other people, personal experiences, care and concern for home and the context of other places.’ Physical geographers argue that place is a specific location or point on the earth’s surface (Castree, Citation2009), be it the atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere or the lithosphere (Gregory, Citation2009). However, human geographers have gone a step further to bring more understanding of place; not only as a location on the earth’s surface but that which comprises of the soil, natural and cultural landscapes, climate, habits, beliefs and way of life of people which includes their action and inaction (Cresswell, Citation2009). The concept of place has other meaning such as a sense of place’ (which is the subjective feeling (imaginative and affective feeling) of a place carried inside an individual or group that gives them an identity); and ‘place as locale’ (which set place as where people have lived experiences in real-time and could be shared by many people at different places each having their own lived experiences) (Castree, Citation2009; Cresswell, Citation2009).

There is no single definition of place. Different kinds of places have different meanings (Gustafson, Citation2001) to both physical and human geographers depending on the process or phenomenon under consideration, which is primarily influenced by the human-environment relationship. In recent times, the upscaling of place expressed through research studies by both human and physical geographers continues to (re)shape our thinking on how we perceive human-environment relationship issues like climate change.

2.2 Ecological place meaning

The last two decades have witnessed a growing body of literature exploring a dimension of our sense of place, i.e. ecological place meaning, which is the natural or environmental dimensions of our perception of places (Brehm et al., Citation2013; Farnum et al., Citation2005; Kudryavtsev et al., Citation2012; Russ et al., Citation2015; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010). The ecological place meaning is ‘the extent to which ecosystem-related phenomena are viewed as valued or important characteristics of places’ (Russ et al., Citation2015, p. 75). Geographers argue that the viewing of nature as a valued component of a place, and most often in combination with solid place attachment, tends to influence pro-environmental behaviour or decision making related to natural resources (Brehm et al., Citation2013; Kudryavtsev et al., Citation2012; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010). Ecological place meaning influences how agroecosystems respond to climate change impact, choice of place-based adaptation options and care for the environment. Places or aspect of a place that holds meaning to people tends to be protected (Manzo & Perkins, Citation2006; Stedman, Citation2003). According to Russ et al. (Citation2015), the protection of nature-related elements of places is inspired by people’s strong ecological place meanings. For example, the use of various climate adaptation strategies by smallholder farmers in SSA to protect their livestock, crops and other agroecological-based livelihoods from climate change impact is a demonstration of ecological place meaning.

2.3 Smallholder Agriculture and place-identity in Sub-Saharan Africa

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), agriculture continues to play a significant role in nations’ economies, accounting for almost 61% of the workforce and contributing about 25% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), Citation2018; Christiaensen & Lionel Demery, Citation2018). The sector is dominated by smallholder farmers who constitute a little over 60% of the region’s entire household population and own 80% of the SSA farmlands, producing about 85% of Africa’s agricultural output (Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), Citation2018; Ayanlade & Radeny, Citation2020). Most of these smallholder farmers owned farmlands with sizes less than 2 ha under rainfed cultivation and predominantly rely on family members as labourers for farm production (Lowder, Citation2016). These farmers identify themselves as peasants – a name that gives them place identity and place attachment (Bryceson, Citation2002; Kansanga et al., Citation2018).

Recently, smallholder farmers’ place-identity has come under pressure from multiple challenges, which has resulted in low productivity of smallholder agriculture (Afful-Koomson et al., Citation2015; Bryceson, Citation2002; Harris & Orr, Citation2014). The chiefest of the challenge is adapting to changing environments and adopting new technologies, including climate-smart technologies, to improve efficiency (Banerjee, et al. Citation2017; Mngoli et al., Citation2015). The challenge of low productivity and some of the proposed solutions, such as increasing smallholder farm sizes, commercialization, livelihood diversification (Harris, Citation2019), are noted to erode farmers’ identity as smallholders, which affect their sense of place (Bryceson, Citation2002; Kansanga et al., Citation2018). A situation Bryceson (Citation2002) describes as deagrarianizationFootnote1 and depeasantizationFootnote2 of smallholding agriculture and rural communities.

3. Place connectedness and place interdependency: globalization of climate change impact on smallholders in Sub-Saharan Africa

Both the discipline of human and physical geography conceptualize place as a location. However, Castree (Citation2009) went a step further to argue that place is not just location but place interconnected and location interdependence. Two different places could be considered homogenous and one based on a phenomenon taking place across them, particularly when giving a local experience a global perspective. Scholars like (Acquah et al., Citation2017; Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2018; Egyir et al., Citation2015; Kumasi et al., Citation2019) were able to show that rural experience of climate change stresses in SSA, such as drought, storms, and floods, have a global implication on food security and rural poverty reduction. The literature (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2018; Acquah et al., Citation2017; Egyir et al., Citation2015; Kumasi et al., Citation2019) used the upscaling of place experience in SSA to illustrate how the local experience of climate-related stress undermines global effort to tackle food production shortfalls to achieve the SDG zero hunger target of 2030. This phenomenon of the oneness of multiple locations is associated with the ‘glocalization’ of places (Castree, Citation2009).

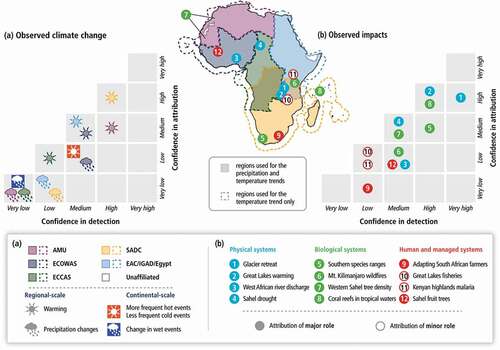

The conceptualization of a globalized world, which is places connected and interdependent, explains how the local place phenomenon has global implications. For instance, place experiences such as harvest failures, low crop yields, poverty, malnutrition, reduced biological productivity, forest loss, continuous land degradation, reduction in livestock, loss of non-timber products, and the loss of arable lands for crop cultivation in rural Ghana are the externalities of global climate change (Asante & Amuakwa-Mensah, Citation2014; Sadiq et al., Citation2019). This place experience is considered to undermine global effort in tackling issues such as rural poverty and food insecurities (Dixon & Stringer, Citation2015; E. Fraser et al., Citation2016). It is also essential to mention that literature use place as a geographic location () (Niang et al., Citation2014) to show the climate change observe and impact across different geographic regions in Sub-Saharan Africa. This illustration altogether draws attention to Geographer Yi-Fu Tuan classically definition of place as ‘field of care and center of meaning’ (Tuan, Citation1977, p. 235)

Figure 1. Observed climate change and impact across Sub-Saharan Africa.

4. Place-based adaptation strategies to climate change by smallholder farmers

Human Geographers have argued that there is interconnection and place interdependence, which makes two places look homogenous. Nevertheless, there are no two same places (Dicken, Citation2004). Furthermore, human geographers have argued that different places react to and are moulded differently even when subjected to the same global force (Castree, Citation2009; Cresswell, Citation2009). Climate change is a global force, and farmers at various SSA locations react differently to this phenomenon, as noted in the literature. According to Agyei (Citation2016), Antwi-Agyei et al. (Citation2015), Williams et al. (Citation2017), and Wrigley-Asante et al. (Citation2019), farmers adopt three main strategies: on-farm strategies, off-farm strategies and indigenous adaptation strategies as risk mitigation measures to reduce climate change impact on their livelihood. These adaptation strategies and lifeworld experiences give meaning to place (Nyong et al., Citation2007).

4.1 On-farm adaptation strategies

4.1.1 Agricultural intensificationFootnote3 at old farm location

Giving another definition of place as location, which is a particular point in space with coordinates according to Cresswell (Citation2009) and place(s) as lived experiences and lifeworld (Castree, Citation2009), the literature conceptualizes place as where farmers go to and what they do there to adapt to climate variability. For instance, in Ghana’s semi-arid regions, farmers use the same piece of farmland to practice mixed crop farming, stone bonding, dry season farming using irrigation, and or turn to adopt improved seeds (Ahmed et al., Citation2016; Ndamani & Watanabe, Citation2016). Another place-based experience noted by (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2015; Kumasi et al., Citation2019; Sadiq et al., Citation2019; Wrigley-Asante et al., Citation2019) suggested that intensification by some smallholders involves the use of drought resistance variety crop, fertilizer application and efficient use of labour on that same piece of land. To other farmers, adaptation at a particular location involves intercropping and mulching practices (Acquah et al., Citation2017; Fagariba et al., Citation2018; Appiah, Citation2019; Wrigley-Asante et al., Citation2019; thereby leading to increased productivity. In cocoa-growing locations in Ghana, farmers usually plant shade trees to protect the cocoa plants from the effect of high temperatures (Abdulai et al., Citation2018). These place experiences and human-environment interaction give these farmers identity as smallholders and shapes how they adapt to climate perturbation to build a sustainable livelihood. Ultimately, environmental phenomena such as climate change and people’s sense of place influence local communities’ adaptation decision-making (Russ et al., Citation2015).

4.1.2. Re(new) location: agricultural extensificationFootnote4

Human geographers have argued that place, which could mean a particular location or points in space and or people’s action that gives them identity (Castree, Citation2009; Gregory, Citation2009), helps us better understand human-environment relationship interaction. The literature highlighted that what gives farmers identity in some places at the height of climate shocks is to choose a new place to farm, an act known as agricultural extensification. Agriculture extensification to some farmers means cultivating multiple farms at different locations and stage seedlings between them (Derbile et al., Citation2016). Other smallholders practice land rotation, which involves relocating farm plots to use new lands (Lawson et al., Citation2019). This farming experience at the new location contributes significantly to environmental preservation through agrochemical and fertilizer reduction on old farm plots. This action promotes better environmental stewardship of old farm places through improved soil and water conservation practices (Kumasi et al., Citation2019; Sadiq et al., Citation2019). Research findings from Agyei (Citation2016) suggest that the choice of a new location for some other smallholders is the river bank. From the literature, we can conceptualize a place as a location where farmers cultivate new farms and a place that embodies lived experiences largely influenced by human-environment interaction. These experiences are different from one person to another, but they give identity to these smallholder farmers. This experience confirms Castree’s (Citation2009) and Cresswell’s (Citation2009) assertions that different places react to and are moulded differently when subjected to the same global force.

4.2. Place as location of off-farm adaptation strategies

Place experience, difference, and lifeworld have been much of an attention to human geographers as people in places would either have their agency to practice what attached them to a place or be victims of global forces that overwhelm them (Castree, Citation2009). According to Castree (Citation2009, p. 153), places could mean the ‘scale of everyday life.’ This embodies lived experience and action of people, which gives them an identity in a particular place. Furthermore, ‘people do things in place. What they do, in part, is responsible for the meanings that a place might have’ (Cresswell, Citation2009, p. 2). Smallholder farmers grappling with the impact of climate change on their livelihood in SSA have found a coping mechanism through their human agency. In a most remote part of West African nations, coping mechanisms, such as engagement in seasonal labour jobs like mason, carpentry, motor mechanic, vehicles tyre repairs, were noted to be the practices that keep some farmers at the place they call home (Acquah et al., Citation2017; Assan et al., Citation2018; Fagariba et al., Citation2018). Place experiences of other farmers is the engagement in livelihood diversification through petty trading activities like selling charcoal and or firewood gathered from the forest as well as selling of livestock (Abdulai et al., Citation2018; Assan et al., Citation2018; Kumasi et al., Citation2019; Ndamani & Watanabe, Citation2016; Yaro et al., Citation2015). In rural Tanzania, increased dependency on provisioning ecosystem services and exhausting of assets holdings are noted as smallholders’ adaption strategies (Enfors & Gordon, Citation2008). These, according to the literature, unleash farmers’ capacity to adapt to climate change, diversify their income, reserve food for their household and enhance their livelihood (Enfors & Gordon, Citation2008).

As climate vulnerability exacerbates, some farmers migrate to look for work as the only option to deal with climate shocks (Agyei, Citation2016; Assan et al., Citation2018; Kumasi et al., Citation2019). Scholars such as Agyei (Citation2016), Antwi-Agyei et al. (Citation2018), and Sadiq et al. (Citation2019) note that only male farmers predominantly migrate to cities and urban areas to look for a job. In contrast to the assertion that only men migrate to search for job opportunities, Kumasi et al. (Citation2019) note that most females also migrate to urban areas and other rural areas temporarily in search of job opportunities. The place concept helps us understand how farmers’ activities and experiences away from the normal farm work in rural communities can enhance their resilience to climate change. Smallholders migrating action to a new place as an adaptation to climate shocks at their former place is shaped by what their former place means to them. As Geographers suggested, what people do in place is responsible for the meaning place has (Cresswell, Citation2009). In arid and semi-arid regions in Ghana, the singular agency that keeps smallholder farmers attached to their place but detached from their farms in times of climate vulnerability is a complete change in social behaviour (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2015, Citation2018). The literature notes that farmers change diets or reduce food consumption to adapt to climate change (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2015, Citation2018). Scholars like Assan et al. (Citation2018) note that frequent borrowing of money from neighbours and other social groups is the strategy most female farmers use to adapt to climate shocks on their livelihood. Furthermore, Kumasi et al. (Citation2019) note that smallholder farmers usually get involved in communal pooling, joint ownership, and sharing of either wealth, labour, or incomes across households; as an adaptation strategy to climate change impact. The action of these farmers gives meaning to place and how climate perturbations shape place experiences.

4.3 Sense of place and indigenous adaptation strategies

Geographers argue that historical and experiential knowledge of a place that helps us imagine a sustainable future reflects our sense of place (Adams, Citation2016). Indigenous or traditional knowledge and experiences are practices passed down by people in places from generation to generation. Personal experiences, stories, emotions, and actions are an expression of different dimensions of our lives, and such function is a description of our sense of place (Adams, Citation2016; Horlings, Citation2015). Ostensibly, geographers have argued a linear relationship between the sense of place and people’s actions (Raymond et al., Citation2017; Seamon & Sowers, Citation2008). The literature illustrated how the sense of place is conceptualized in smallholders’ indigenous adaptation strategies to climate shocks using life experiences passed down to adapt to climate change. Ahmed et al. (Citation2016) note the experience of seed and water preservation, land and post-harvest management practices to adapt to climate change by some farmers is an expression of their sense of place. Antwi-Agyei (Citation2015) notes that farmers use the flowering and fruiting of certain trees like the Baobab and Shea tree to indicate the coming rainy season to plough farms for cultivation. In this instance, the lens through which the environment is observed enables farmers to make meaning from signs and signifiers. For example, based on their life experiences, the flowering and fruiting of particular plants predict a rainy season. This experience confirms the longstanding argument that some people’s sense of place becomes the lens through which life experiences makes meaning at a particular place (Russ et al., Citation2015). Beyond the emotional connections and how needs are met to inform a sense of place and environmental awareness about a place, the physical characteristics of a place, activities and images of place also tell a sense of place.

Furthermore, apart from nomadic pastoralist mobility through seasonal movement, smallholder farmers in the Sahelian region of Africa are known to decide on cropping patterns, use of emergency fodder in times of drought, and multi-species composition of herds to survive extreme shocks (Nyong et al., Citation2007). The knowledge to undertake these activities and the activities themselves, the literature argues, is shaped by these farmers’ meaning of place. For instance, Nyong et al. (Citation2007) argue that knowledge on climate change adaptation creates a moral economy with culturally attached rules that provide a sense of community, belonging and stability to smallholder farmers.

Geographers such as Adams (Citation2016) and Nyong et al. (Citation2007) assert the use of indigenous knowledge, and in this case, indigenous adaptation technique to climate change is an expression of smallholder farmers’ sense of place because such action agrees with smallholders’ identities, social interactions, and lived experiences. Furthermore, scholars such as Relph (Citation2015), Seamon and Sowers (Citation2008), and Turner and Turner (Citation2006) note that the bond between people and places reflects their attachment to a place and its given expression in their action. According to Derbile et al. (Citation2016), some indigenous adaptation strategies that help farmers bond with their place cultivate multiple farms and stage seedlings between them. Some other indigenous knowledge used by smallholders in SSA to adapt to climate change is changing planting dates and reducing farm size (Acquah et al., Citation2017). Other smallholders use simple farm tools, root and tuber processing, and social grouping (Egyir et al., Citation2015) to demonstrate traditional or indigenous knowledge passed on to enhance resilience to climate change in their communities. What is evident from the literature is that farmers’ sense of place in times of climate perturbations is expressed in how they use indigenous knowledge passed on to them to build resilience to climate-related stress on their livelihood.

5. Sense of place and determinant and barriers to effective adaptation strategies

People’s thoughts, perceptions and feelings towards a particular place are as real and tangible as the place in question (Castree, Citation2009; Cresswell, Citation2009; Creswell, Citation2014:Seamon & Sowers, Citation2008). Furthermore, geographers argue that the feeling or perception people carry about fosters a sense of attachment and belonging to a particular place they inhabit (Adams, Citation2016; Agnew, Citation1989; Altman & Low, Citation1992). Likewise, the perception about a particular place-phenomenon might differ among different people due to the singularity of sense of place (Dicken, Citation2004; Preston, Citation2015). The literature conceptualizes determinants of adaptation strategies and barriers to effective adaption by smallholder farmers as an expression of their sense of place.

According to Agyei (Citation2016), the choice of farmers’ adaptation strategies to climate shocks depends on farmers’ intuition, historical experiences, knowledge of a particular strategy, and resources’ availability to implement the strategy. Ndamani and Watanabe (Citation2016) note smallholders perceive their level of education, family size, annual household income, access to climate information, access to financial credits and being a member of a farmer-based organization plays a crucial role in influencing a particular adaptation strategy. The literature notes that some smallholders perceive farmers’ age, residential status (immigrant/indigene), and power relations at home are the key factors influencing female farmers’ choice of adaptation strategies (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2015; Lawson et al., Citation2019). Elsewhere in the Nile Basin of Ethiopia, Ayanlade et al. (Citation2018) note, years of farming experience, social capital, and agro-ecological settings influence farmers’ perception of climate change and choice of adaptation strategies. Other suggestions such as; the degree of soil fertility in a particular place (Tambo, Citation2016); rainfall patterns (Sadiq et al., Citation2019); other socioeconomic factors and land tenure system (Acquah et al., Citation2017; Fosu-Mensah et al., Citation2012) are what some farmers perceive and carry within them as place-based challenges that influence their ability to adapt to local climate perturbations. Elsewhere, physical characteristics and component place such markets, roads (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2012), farm equipment, soil texture (Acquah et al., Citation2017), waterbody and trees (Apuri et al., Citation2018), as well as the experiences and activities that surround them influences adaptation strategies through smallholders’ sense of place.

In demonstrating the nuances of sense of place, the literature notes that apart from financial constraints, some rural farmers perceive institutional and technological barriers (Antwi-Agyei 2015; Acquah et al., Citation2017; Fosu-Mensah et al., Citation2012) are the bottlenecks that hinder effective adaptation to the vagaries of climate change. Ahenkan et al. (Citation2018) note some farmers feel the lack of participation from private sector groups like insurance companies, agro-input dealers due to inadequate government incentives hinders effective adaptation to climate shocks. The place intuition and conviction, such as farmers’ beliefs that adverse climate effects are due to ancestral curses or punishment from their deity (Ndamani & Watanabe, Citation2016), also act as barriers to effective adaptation to climate change. The literature notes the perceptions of place-based constraints and determinants of adaptation strategies differ from farmer to farmer. The differences in perceptions of various farming groups across SSA point to the fact that there is no two sense of place. However, these multiple senses of places are interconnected and influence each other through farmers’ lived experiences and other stakeholders’ actions.

6. Place sustainability and maladaptation outcome of adaptation strategies

Geographers such as Gregory (Citation2009, p. 173) note that ‘place warrants greater explicit attention by physical geographers in relation to the management of sustainable physical environment.’ According to Gregory (Citation2009), the environmental management of places could be done well through a more culturally accepted model that agrees with the United Nations (UN) meaning of sustainable development, i.e. respects future generations’ life quality through the enhancement of earth’s resources and the ecosystem. Nevertheless, when it comes to climate change adaptation among smallholder farmers in Ghana, Antwi-Agyie et al. (Citation2018) and Agyei (Citation2016) mentioned that most of the place-based adaptation strategies employed by these smallholder farmers erodes sustainable development and leads to maladaptation outcomes.

For instance, smallholders’ behaviour, such as the overuse of fertilizer on farms or near riverbanks, ends up either enriching soil nutrients that kill soil microbes or leaks into water bodies Agyei (Citation2016) to cause eutrophication. This situation later results in excessive algae bloom, depleting the amount of oxygen in water, thereby destroying other marine organisms. Also, neither the destruction of woodland for firewood and inefficient charcoal burning, as noted by Yaro et al. (Citation2015), nor the deforestation and burning of other places to make room for farming in a new location as Appiah et al. (Citation2018) noted leads to sustainable development. The scenario above conceptualizes place as locations connected and interdependence to explain that environmental problems such as water pollution and loss of soil microbes result from human-environment interaction at another location. However, the externalities of such action are experienced at another location.

In another instance, the literature noted adaptation strategies like migration impact negatively on social amenities in major cities. Migration is recognized to increase pressure on dwindling social services provision in urban areas and reducing farm labour efficiency if migrants don’t return early before the farming season begins (Antwi-Agyei et al., Citation2018). This situation affects farm labour productivity and operations, according to Antwi-Agyei et al. (Citation2018). Furthermore, place experiences such as the lack of irrigation facilities tend to increase conflict in these farming communities because of competing demand for water resources during the dry season. Again, adaptation strategies such as livestock selling deplete the population of livestock, exacerbating poverty levels in rural communities (Haggblade et al., Citation2010). A look at another adaptation strategy, such as selling manpower labour to other farmers, rob smallholders of the time needed to plough their farms (Antwi-Agyie et al., Citation2018). These assertions point to the fact that place-based adaptation strategies adopted by smallholder farmers in Ghana are not sustainable within the context of rapidly changing climatic conditions and lead to maladaptation outcomes. In recent times, a lot of question has been asked about the sustainability of indigenous adaptation strategies since average temperature across Ghana, and other Sub-Saharan Africa nations are projected to increase approximately +2.0°C and +4.5°C by 2100 (Müller, Citation2009). What is evidence in literature from all these maladaptation outcomes is that place as location, sense of place, experiences and lifeworld activities that give smallholder farmers identity warrant greater attention to enhancing sustainable livelihood.

7. Key argument and critical standpoint

The paper argues that place as a geographic concept was used in diverse ways in climate change adaptation and smallholders’ literature. First, to show how places are interconnected and interdependent of locations. Whatever is happening at a remote location could be upscaled to represent a global phenomenon, a situation Castree (Citation2009) refers to as the ‘glocalization’ of places. The literature illustrated how a local phenomenon in smallholding communities, such as harvest failures, low crop yields, poverty, malnutrition, reduced biological productivity, forest loss, continuous land degradation, and reduction in livestock, are externalities of climate change in SSA. However, these externalities undermine global efforts to reduce poverty, achieve global food security and build a sustainable livelihood.

Place as locale shows how people have a degree of agency to decide how to control their destiny irrespective of what global forces impact their livelihoods. The review illustrated this gesture by explaining how smallholders use multiple strategies to adapt and mitigate climate impact on their livelihood. What is critical about this place experience is that farmers make personal choices that are heavily influenced by place experience. A striking feature in this paper is that sense of place could be carried inside people and reflect their actions. The sense of place plays a critical role in what farmers perceive to be barriers to climate change adaptation as well as influencing the choice of farmers’ adaptation strategies. The review illustrated how indigenous knowledge, which binds people and places together, is scale-out as climate mitigation and adaptation measures among smallholders. Ostensibly, how people behave and act is essentially a reflection of their sense of place. illustrates how the literature engages the concept of place to describe smallholder farmers’ adaptation strategies to change Ghana.

Table 1. Place concept in smallholders and climate change adaptation literature

The review opens up an opportunity to explore how place as locale is conceptualized in the farmer–market relationship (i.e. demand and supply of farm produce) to influence smallholder farmers’ adaptation strategies. For instance, Antwi-Agyie et al. (Citation2015), Kumasi et al. (Citation2019), Wrigley-Asante et al. (Citation2019), and Sadiq et al. (Citation2019) suggested that some farmers adapt to climate shocks by using improved seeds, fertilizer and other agrochemicals, which tends to improve their yield. However, it is essential to mention that the availability and accessibility of the market for farm produce have the tendency to act as a ‘global force’ to shape farmers’ response to climate vulnerability, considering the financial investment required to adopt such a strategy. Scholars such as Polanyi (Citation2001) note that markets play a critical role in labour division within societies. They serve as the force that pulls production, and hence when it is omitted in the production value chain of the division of labour; it trickles down to affect production. Therefore, it makes sense to argue that farmers who invested in improved technologies do so because the market is available for farm produce and those who don’t lack market access. The presence or absence of a market then acts as a place that influences another place’s experience. This scenario confirms the interconnection and interdependence of place to influence people’s behaviour, according to Castree (Citation2009) and Cresswell (Citation2009).

In the case of farmers who use migration as an adaptation strategy (Agyei, Citation2016; Assan et al., Citation2018; Kumasi et al., Citation2019), the literature presents us with another opportunity to explore how smallholders’ sense of place is interrupted by the pull/push factors acting as a catalyst for migration. Geographers like Gustafson (Citation2001) note that continuity is an essential aspect of a place’s self-related meanings. This implies, people’s actions and experiences in a particular place are bound to continue unless their sense of place attachment is interrupted, as it were. Talking about discontinuity, Lindsay et al. (Citation2012) notes that indigenes who lose their lands and forest in the Philippines to big companies for palm plantations had to shift their sense of place to a new landscape. The use of migration as an adaptation strategy to climate shocks on rural livelihood presents us an opportunity to explore how the interruption of smallholders’ sense of place by push/pull factors interplay here. Scholars like E. D. G. Fraser et al. (Citation2011) note that migrants escaping the vagaries of climate stress on their livelihood in their homeland will search for new opportunities in another place. These new opportunities are for survival and not necessarily borne out of choice (Ellis, Citation2000), with others having grave implications on eroding farmers’ identity and sense of place (Bryceson, Citation2002).

Again, we can deduce from the literature another opportunity to understand how place as locale is conceptualized in how government policy and decision-making machinery influences smallholder farmers’ adaptation strategies. According to geographers, place is continuously shaped by people with power and authority (Lowan-Trudeau, Citation2017; Upham et al., Citation2018). This review-work noted that in the West African nation of Ghana, cocoa farmers were able to invest in shade trees as an adaptation strategy (Abdulai et al., Citation2018) because they received government incentives and subsidies to boost cocoa production due to cocoa’s importance as a foreign exchange earner to the economy (MoFA, Citation2018). In contrast, Williams et al. (Citation2017) note that the lack of government incentives and subsidies to pineapple producers constrains effective adaptation to climate perturbations. The connection between people, place and power is worth investigating to understand how place and place experience is (re)shaped by people in power through policy.

From the literature, ecological place meaning was central to how farmers perceived climate change vagaries, determinants of adaptation strategies, and barriers to effective adaptation strategies (). This confirms the longstanding argument that ‘ecological place meaning is nurtured through direct experiences with the urban environment’ (Russ et al., Citation2015, p. 74). The extent to which the literature glocalized climate experience in SSA and draws attention to smallholders’ experiences and adaptation strategies such as on-farm, off-farm and indigenous techniques demonstrates that places or aspect of a place holding meaning to people tends to be protected (Manzo & Perkins, Citation2006; Stedman, Citation2003).

8. Conclusion

This paper expands on the meaning of place in geography by opening a new narrative of how the geographic concept of place is conceptualized in smallholder farmers and climate change adaptation literature in SSA. We can see from the literature how places are connected and interdependent to represent a homogenous place. Whatever is happening at a remote location could be upscaled to represent a global phenomenon, a situation Castree (Citation2009) refers to as the ‘glocalization’ of places. The paper pointed out that people in places have the agency to control their destinies irrespective of whatever global force overwhelms their livelihoods and means of survival, something which is demonstrated in the various adaptation strategies employed by smallholder farmers in Ghana. Ostensibly, people’s sense of place, which is subjective in themselves, is carried within by each person and reflects in their actions.

The literature describes place as the ‘where’ of a location and locations geographically interconnected and interdependent to draw a connection between how climate change impact and farmers’ experience in SSA interact with global efforts such as improving food security, eliminating poverty and building a sustainable rural livelihood. We also expand on the geographic concept of place by asserting there is no one meaning of place as suggested by Castree (Citation2009), Cresswell (Citation2009), and Gregory (Citation2009). Places shape people’s intuition, believes, actions and experiences. The concept of the place gives people identity and how they respond to global forces that influence their way of life. Place influences people’s actions and vice versa. What gives meaning to a place goes beyond a geographic location in space. It embodies people’s thoughts, perceptions and feelings. The paper argues that there is an undeviating relationship between what place is and humans’ lifeworld experience and as it could be re(shaped) by people in power. Further exploration of the relationship between lifeworld experiences, people, and power is central in understanding the meaning of place.

Author's note: What is place, and how does it mean in the daily experiences of smallholder farmers adapting to the brunt of global climate change? Is it a location, a locale and or a sense of place? This paper is part of the author's doctoral research work, which explores to understand how adaptation to climate change, particularly the use of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices and technologies, promotes sustainable food systems outcomes for smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgments

I thank my academic supervisor, Prof. Evan D.G Fraser, for his continuous support of my studies. I commend Prof. Noella Gray for her excellent facilitation of the Geography course, particularly concerning geographic concepts, philosophical approaches, debates etc., and most importantly, for inspiring this work. I thank Richard Nyiawung and Emily Smit for their review and constructive feedback on this paper’s first draft. Finally, I appreciate the valuable suggestions from the two anonymous reviewers. I am entirely responsible for any remaining shortcomings in interpretation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Deagrarianization is defined as a long-term process of occupational adjustment, income earning reorientation, social identification and spatial relocation of rural dwellers away from strictly agricultural-based modes of lively hood. Depeasantization has now begun, representing a specific form of deagrarianization in which peasantries lose their economic capacity and social coherence, and shrink in demographic size relative to non-peasant populations (Bryceson, Citation1996; Bryceson, Citation2002, p. 726).

2. Depeasantization … represents a specific form of deagrarianization in which peasantries lose their economic capacity and social coherence, and shrink in demographic size relative to non-peasant populations (Bryceson, Citation2002, p. 727).

3. Agriculture Intensification involves the use of scientific tools, techniques, approaches and mechanisms to increase agricultural yield from existing agricultural footprint or same piece of land at a given location (Evans, Citation2009; Godfray & Garnett, Citation2014).

4. Agricultural Extensification refers to taking over new farming territories, including forest and reserved lands for agricultural purposes (Godfray & Garnett, Citation2014). The choice for farm relocation, a new or an additional farm investment similar to the adage ‘don’t put all your eggs in one basket’ is another approach used by farmers to adapt to climate change in rural Ghana.

References

- Abdulai, I., Jassogne, L., Graefe, S., Asare, R., Asten, P. V., Läderach, P., & Vaast, P. (2018). Characterization of cocoa production, income diversification and shade tree management along a climate gradient in Ghana. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0195777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195777

- Acquah, S., Kendie, S., & Agyenim, J. B. (2017). Determinants of rural farmers’ decision to adapt to climate change In Ghana. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 62(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18551/rjoas.2017-02.23

- Adams, J. (2016, May 26). Sense of place. The Nature of Cities. https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2016/05/26/sense-of-place/

- Adger, W., Huq, S., Brown, K., Conway, D., & Hulme, M. (2003). Adaptation to climate change in the developing world. Pds, 3, 179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1464993403ps060oa

- Afful-Koomson, T., Fonta, W., Frimpong, S., & Amoh, N. (2015). Economic and financial analyses of small and medium food crops agro-processing firms in Ghana. Accra: United Nations University Institute for Natural Resources in Africa (UNU-INRA.

- Agnew, J. (1989). The devaluation of place in social science. In J. Agnew & J. Duncan (Eds.), The power of place (pp. 9–30). Allen & Unwin.

- Agyei, F. K. (2016). Sustainability of climate change adaptation strategies: Experiences from Eastern Ghana. Environmental Management and Sustainable Development, 5(2), 84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5296/emsd.v5i2.9845

- Ahenkan, A., Osei, J., & Owusu, E. H. (2018). Mainstreaming Green Economy: An Assessment of Private Sector Led Initiatives in Climate Change Adaptation in Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(2), 77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v11n2p77

- Ahmed, A., Lawson, E. T., Mensah, A., Gordon, C., & Padgham, J. (2016). Adaptation to climate change or non-climatic stressors in semi-arid regions? Evidence of gender differentiation in three agrarian districts of Ghana. Environmental Development, 20, 45–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2016.08.002

- Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). (2018). Africa’s agriculture status report.

- Altman, I., & Low, S. M. (1992). Preface. In I. Altman & S. M. Low (Eds.), Place attachment (pp. xi–xii). Plenum Press.

- Antwi-Agyei, P., Dougill, A. J., Stringer, L. C., & Codjoe, S. N. A. (2018). Adaptation opportunities and maladaptive outcomes in climate vulnerability hotspots of northern Ghana. Climate Risk Management, 19, 83–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2017.11.003

- Antwi-Agyei, P., Dougill, A. J., & Stringer, L. C. (2015). Barriers to climate change adaptation: Evidence from northeast Ghana in the context of a systematic literature review. Climate and Development, 7(4), 297–309. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.951013

- Antwi-Agyei, P., Fraser, E. D. G., Dougill, A. J., Stringer, L. C., & Simelton, E. (2012). Mapping the vulnerability of crop production to drought in Ghana using rainfall, yield and socioeconomic data. Applied Geography, 32(2), 324–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.06.010

- Appiah, D. O. (2019). Climate policy research uptake dynamics for sustainable agricultural development in Sub-Saharan Africa. GeoJournal, 1–13. ABI/INFORM Global; Agricultural & Environmental Science Collection; International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09976-2

- Appiah, D. O., Akondoh, A. C., Tabiri, R. K., & Donkor, A. A. (2018). Smallholder farmers’ insight on climate change in rural Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 4(1). Agricultural & Environmental Science Collection. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1436211

- Apuri, I., Peprah, K., & Achana, G. T. W. (2018). Climate change adaptation through agroforestry: The case of Kassena Nankana West District, Ghana. Environmental Development, 28, 32–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2018.09.002

- Asante, F., & Amuakwa-Mensah, F. (2014). Climate change and variability in Ghana: Stocktaking. Climate, 3(1), 78–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/cli3010078

- Assan, E., Suvedi, M., Schmitt Olabisi, L., & Allen, A. (2018). Coping with and adapting to climate change: A gender perspective from smallholder farming in Ghana. Environments, 5(8), 86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/environments5080086

- Awunyo-Vitor, D. (2017). Factors Influencing Choice Of Climate Change Adaptation Strategies By Maize Farmers In Upper East Region Of Ghana. 13(2), 15

- Ayanlade, A., & Radeny, M. (2020). COVID-19 and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of lockdown during agricultural planting seasons. Npj Science of Food, 4(1), 13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-020-00073-0

- Ayanlade, A., Radeny, M., & Akin-Onigbinde, A. I. (2018). Climate variability/change and attitude to adaptation technologies: A pilot study among selected rural farmers’ communities in Nigeria. GeoJournal, 83(2), 319–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9771-1

- Banerjee, S. G., Malik, K., Tipping, A., Besnard, J., & Nash, J. (2017). Double dividend: Power and agriculture nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Group.

- Brehm, J. M., Eisenhauer, B. W., & Stedman, R. C. (2013). Environmental concern: Examining the role of place meaning and place attachment. Society and Natural Resources, 26, 522–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2012.715726

- Bryceson, D. F. (1996). Deagrarianization and rural employment in sub-Saharan Africa: A sectoral perspective. World Development, 24(1), 97–111

- Bryceson, D. F. (2002). The scramble in Africa: Reorienting rural livelihoods. World Development, 30(5), 725–739. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00006-2

- Castree, N. (2009). Place: Connection and boundaries in interdependent world. In A. C. Stuart & G. Valentine (Eds.), Approaches to human geography: Philosophies, theories, people and practices (2nd ed., pp. 153–172). Sage Publication.

- Christiaensen, L., & Lionel Demery, E. (2018). Agriculture in Africa; Telling the myth from the fact. Direction in development. The WorldBank Group.

- Cresswell, T. (2009). Place. Elsevier Inc.

- Creswell, T. (2014). Place. In N. C. Roger Lee (Ed.), The sage handbook of human geography (Vol. 1, pp. 1–21). Sage Publication.

- Derbile, E. K., Jarawura, F. X., & Dombo, M. Y. (2016). Climate change, local knowledge and climate change adaptation in Ghana. In J. A. Yaro & J. Hesselberg (Eds.), Adaptation to climate change and variability in rural West Africa (pp. 83–102). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31499-0_6

- Dicken, P. (2004). Geographers and “globalization”: (Yet) another missed boat? Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00111.x

- Dixon, J. L., & Stringer, L. C. (2015). Towards a theoretical grounding of climate resilience assessments for smallholder farming systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Resources; Basel, 4(1), 128–154. http://dx.doi.org.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/10.3390/resources4010128

- Egyir, I. S., Ofori, K., Antwi, G., & Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y. (2015). Adaptive capacity and coping strategies in the face of climate change: A comparative study of communities around two protected areas in the coastal savanna and transitional zones of Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v8n1p1

- Ellis, F. (2000). The Determinants of Rural Livelihood Diversification in Developing Countries. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 51(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2000.tb01229.x

- Enfors, E. I., & Gordon, L. J. (2008). Dealing with drought: The challenge of using water system technologies to break dryland poverty traps. Global Environmental Change, 18(4), 607–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.006

- Evans, A. (2009). The feeding of the nine billion: Global food security for the 21st century. Royal Institute of International Affairs.

- Fagariba, C., Song, S., & Soule Baoro, S. (2018). Climate change adaptation strategies and constraints in northern ghana: evidence of farmers in Sissala West District. Sustainability, 10(5), 1484. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051484

- Farnum, J., Hall, T., & Kruger, L. E. (2005). Sense of place in natural resource recreation and tourism: An evaluation and assessment of research findings (PNW-GTR-660; p. PNW-GTR-660). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2737/PNW-GTR-660

- Fosu-Mensah, B. Y., Vlek, P. L. G., & MacCarthy, D. S. (2012). Farmers’ perception and adaptation to climate change: A case study of Sekyedumase district in Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 14(4), 495–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-012-9339-7

- Fraser, E., Legwegoh, A., Kc, K., CoDyre, M., Dias, G., Hazen, S., Johnson, R., Martin, R., Ohberg, L., Sethuratnam, S., Sneyd, L., Smithers, J., Van Acker, R., Vansteenkiste, J., Wittman, H., & Yada, R. (2016). Biotechnology or organic? Extensive or intensive? Global or local? A critical review of potential pathways to resolve the global food crisis. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 48, 78–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2015.11.006

- Fraser, E. D. G., Dougill, A. J., Hubacek, K., Quinn, C. H., Sendzimir, J., & Termansen, M. (2011). Assessing vulnerability to climate change in dryland livelihood systems: Conceptual challenges and interdisciplinary solutions. Ecology and Society, 16, 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03402-160303

- Godfray, H. C. J., & Garnett, T. (2014). Food security and sustainable intensification. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 369(1639), 1–10.

- Gregory, K. (2009). Place: The management of sustainable physical environments. In A. C. Stuart & G. Valentine (Eds.), Approaches to human geography: Philosophies, theories, people and practices (2nd ed., pp. 173–198). Sage Publication.

- Gustafson, P. (2001). Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 5–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2000.0185

- Haggblade, S., Hazell, P., & Reardon, T. (2010). The rural non-farm economy: Prospects for growth and poverty reduction. World Development, 38(10), 1429–1441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.008

- Harris, D. (2019). Intensification benefit index: How much can rural households benefit from agricultural intensification? Experimental Agriculture, 55(2), 273–287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479718000042

- Harris, D., & Orr, A. (2014). Is rainfed agriculture really a pathway from poverty? Agricultural Systems, 123, 84–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2013.09.005

- Horlings, L. G. (2015). Values in place; A value-oriented approach toward sustainable place-shaping. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 257–274.

- IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Kansanga, M., Andersen, P., Kpienbaareh, D., Mason-Renton, S., Atuoye, K., Sano, Y., Antabe, R., & Luginaah, I. (2018). Traditional agriculture in transition: Examining the impacts of agricultural modernization on smallholder farming in Ghana under the new Green Revolution. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 26(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2018.1491429

- Kudryavtsev, A., Stedman, R., & Krasny, M. (2012). Sense of place in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 18(2), 229–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.609615

- Kumasi, T. C., Antwi-Agyei, P., & Obiri-Danso, K. (2019). Smallholder farmers’ climate change adaptation practices in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 21(2), 745–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-0062-2

- Lawson, E. T., Alare, R. S., Salifu, A. R. Z., & Thompson-Hall, M. (2019). Dealing with climate change in semi-arid Ghana: Understanding intersectional perceptions and adaptation strategies of women farmers. GeoJournal. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09974-4

- Lindsay, E., Convery, I., Ramsey, A., & Simmons, E. (2012). Changing place: Palm oil and sense of place in borneo. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography, 6(2), 45–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5719/hgeo.2012.62.45

- Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2017). Indigenous environmental education: The case of renewable energy projects. Educational Studies, 53(6), 601–613. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2017.1369084

- Lowder, S. K., Skoet, J., & Raney, T. (2016). The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Development, 87, 16–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.041

- Manzo, L. C., & Perkins, D. D. (2006). Finding common ground: The importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 20(4), 335–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412205286160

- Mngoli, M., Mkwambisi, D., Fraser, E.D.G. (2015). An evaluation of traditional seed conservation methods in Malawi. Journal of International Development. 27(1): 85–98

- MoFA. (2018). National agriculture investment plan: An Agenda for transforming Ghana’s Agriculture (2018-2021). http://mofa.gov.gh/site/images/pdf/National%20Agriculture%20Investment%20Plan_IFJ.pdf

- Müller, C. (2009). Climate change impact on Sub-Saharan Africa: An overview and analysis of scenarios and models.

- Ndamani, F., & Watanabe, T. (2016). Determinants of farmers’ adaptation to climate change: A micro level analysis in Ghana. Scientia Agricola, 73(3), 201–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-9016-2015-0163

- Niang, I., Urquhart, P., Padgham, J., Lennard, C., Essel, A., Abdrab, M. A., & Ruppel, O. C. (2014). Africa. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 67.

- Nyong, A., Adesina, F., & Osman Elasha, B. (2007). The value of indigenous knowledge in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the African Sahel. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 12(5), 787–797. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-007-9099-0

- Philip Antwi-Agyei, Andrew J. Dougill, Thomas P. Agyekum & Lindsay C. Stringer (2018) Alignment between nationally determined contributions and thesustainable development goals for West Africa. Climate Policy, 18:10, 1296–1312, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1431199

- Polanyi, K. (2001). Evolution of market pattern. In Great transformation: The political and economic origins of our time (pp. 59–70).

- Preston, L. (2015). A global sense of place: geography and sustainability education in a primary context. Social educator, 33(3), 29–41

- Raymond, C. M., Kyttä, M., & Stedman, R. (2017). Sense of place, fast and slow: The potential contributions of affordance theory to sense of place. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01674

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and Placelessness. Pion.

- Relph, E. (2015). Placeness, place, placelessness | Exploring the concept of place, sense of place, spirit of place, placemaking, placelessness and non-place, and almost everything to do with place and places. https://www.placeness.com/

- Russ, A., Peters, S. J., E. Krasny, M., & Stedman, R. C. (2015). Development of ecological place meaning in New York City. The Journal of Environmental Education, 46(2), 73–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2014.999743

- Sadiq, M. A., Al-Hassan, R. M., Alhassan, S. I., & Kuwornu, J. K. M. (2019). Assessing Maize farmers’ adaptation strategies to climate change and variability in Ghana. Agriculture, 9(5). Agricultural & Environmental Science Collection. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9050090.

- Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2010). The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.010

- Seamon, D., & Sowers, J. (2008). Place and placelessness, Edward Relph. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446213742.n5

- Stedman, R. C. (2003). Sense of place and forest science: Toward a program of quantitative research. Forest Science, 49, 822–829.

- Tambo, J. A. (2016). Adaptation and resilience to climate change and variability in north-east Ghana. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 17, 85–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.04.005

- Tuan, Y. F. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Turner, P., & Turner, S. (2006). Place, sense of place and presence. Presence, 15, 204–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.2006.15.2.204

- Upham, P., Johansen, K., Bögel, P. M., Axon, S., Garard, J., & Carney, S. (2018). Harnessing place attachment for local climate mitigation? Hypothesising connections between broadening representations of place and readiness for change. Local Environment, 23(9), 912–919. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2018.1488824

- Williams, P. A., Crespo, O., Atkinson, C. J., & Essegbey, G. O. (2017). Impact of climate variability on pineapple production in Ghana. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(1), 26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-017-0104-x

- Wrigley-Asante, C., Owusu, K., Egyir, I. S., & Owiyo, T. M. (2019). Gender dimensions of climate change adaptation practices: The experiences of smallholder crop farmers in the transition zone of Ghana. African Geographical Review, 38(2), 126–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2017.1340168

- Yaro, J. A., Teye, J., & Bawakyillenuo, S. (2015). Local institutions and adaptive capacity to climate change/variability in the northern savannah of Ghana. Climate and Development, 7(3), 235–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.951018