ABSTRACT

In August 2023, residents of Graaff-Reinet received news that the town’s name is being considered for a change to Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe. Community reactions to the proposed name change have sparked a need to scientifically investigate the opinions of a representative sample of the community regarding the proposed name change. The study employed a quantitative approach, utilizing a representative sample survey with stratified random sampling to ensure diverse population representation from the town. Three strata were identified: former white and former coloured group areas, and the township. A total of 367 interviews were conducted, determined by the physical count of residential erven (7,748) to achieve a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error. The questionnaire gathered data on demographics, opinions on renaming, and connections to Graaff-Reinet. Results indicated that 83.6% expressing the opinion that the name should not change, a sentiment prevalent across all three strata. Reasons against change included familiarity, historical significance, and a focus on service delivery. The study revealed a strong sense of community identity and place attachment. The study highlighted the resistance to changing toponyms as a unifying force in Graaff-Reinet, emphasizing the significance of place names in shaping identity and community dynamics.

1. Introduction

A place name (toponym) serves as one of the elements defining the identity of a place. Toponyms utilize a single word or a series of words to differentiate and characterize one location from another. Beyond aiding in physical navigation, toponyms evoke potent images and connotations, playing a crucial role in shaping and enriching the development of a profound sense of place (Alderman, Citation2008). In a society such as South Africa, marked by a diversity of political and cultural values, alterations in place names can act as either a unifying or divisive catalyst. The re-naming of places in the wake of political transfers of power is a worldwide phenomenon (E. Jenkins, Citation2009). Place name changes is often seen as a symbolic and tangible effort to address the historical injustices and impacts of colonization on indigenous peoples. It reflects a broader movement towards acknowledging and rectifying the negative consequences of colonialism. By renaming places with indigenous names or names that hold cultural significance, there is an attempt to reclaim and preserve indigenous languages, cultures and histories. This process is viewed as a step towards recognizing the rights, identities and contributions of indigenous communities, and challenging the colonial legacy (Andersson, Citation2020; Belshaw, Citation2005; Berg & Kearns, Citation1996; Dube, Citation2018; Helleland, Citation2002; Mbenzi, Citation2019; Swart, Citation2008).

As signifiers of place, ‘place-names can evoke powerful emotions within individuals and groups and they thus conform to the most classic definitions of symbolism’ (Berg & Kearns, Citation1996, pp. 103–104). A member of the ministerial task team for the transformation of the heritage landscape in South Africa stated that as South Africans we should collectively embrace the idea of name changes and unite to establish a set of names that not only mirrors our diversity but also upholds our constitutional principles. According to him, the persistence of numerous unchanged place names is a direct challenge to the dignity of the majority of South Africa’s people. It serves as a tangible reminder of the historical power imbalances in our society. While it is acknowledged that altering names alone won’t bring about a more egalitarian society, it can serve as a symbolic shift (Webb, Citation2018). According to Irvine et al. (Citation2021, p. 333)

toponyms can be conceptualised as both symbolic capital and symbolic resistance – as means to express hegemonic power or to resist it. They have been cast as a means of transformation and restitution in the post-apartheid landscape of South Africa. The naming and renaming process has, therefore, been seen as a political act of representation and part of the nation-building project.

Place names can function as symbols, mobilizing and fostering a political and historical awareness of shared identity, alter identities and foster community unity (Guyot & Seethal, Citation2007). While this phenomenon is frequently demonstrated through activism opposing name changes and the decolonization of urban toponyms, its influence endures (Rammile & Matamanda, Citation2022). Similarly, according to Chauke (Citation2015), the act of changing names can serve as a unifying tool, specifically aimed at promoting and rediscovering the country’s heritage. Webb (Citation2018, n.p.n.) argued that nation building during the Mandela-era was

(mis)interpreted as not tampering with the history and culture of the minority … Those objecting to name changes appear to have failed to grasp that changing geographical names was an integral part of establishing colonial hegemony. Transforming place names should, therefore, form part of decolonising society. There is nothing sacrosanct about colonial and apartheid place names.

The influence and political dynamics associated with naming are particularly conspicuous on the cultural landscape. The South African Geographical Names Council (SAGNC) serves as an advisory body, facilitating name changes through community consultations to provide recommendations to the Minister of Sport, Arts, and Culture. This process involves collaboration with provincial councils and encompasses various geographical features such as cities, towns, villages, rivers, and mountains. Until 1994, the majority of place names in South Africa predominantly mirrored the colonial and apartheid history, values, and interests of the white community. Consequently, it could have been anticipated that under a democratic dispensation certain place names would have been renamed. A case in point in the paper is the small town of Graaff-Reinet located in the Eastern Cape. More than 10 years ago, Ndletyana (Citation2012, p. 93) wrote:

the Eastern Cape has not changed any of its numerous Eurocentric town names, such as … Graaff-Reinet … Instead, the province has preoccupied itself with correcting the spelling of existing names, such as Bisho to Bhisho, Umtata to Umthatha, Idutywa to Dutywa. Jongela Nojozi, chairperson of the province’s Geographical Names Committee, once remarked on South Africa’s public broadcaster’s television programme Asikhulume that the reason the Eastern Cape prioritised orthographic corrections is that it is the least controversial and thus easiest to do. By implication, Nojozi’s committee has avoided major toponymic changes for fear of inciting public outcry.

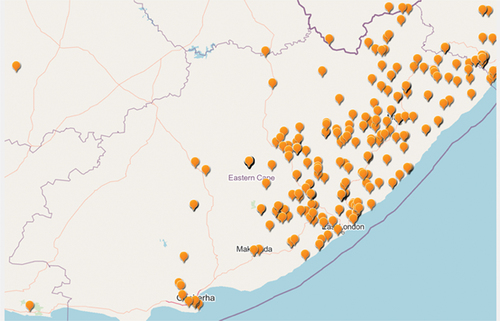

Following the aforementioned statement, several notable towns and cities in the Eastern Cape named after colonial figures have undergone renaming. For instance, Port Elizabeth was renamed Gqeberha, and Grahamstown was renamed Makhanda. The accompanying place-name change map () for the Eastern Cape from the SAGNC illustrate transformations in city, town, and village names, as well as alterations to post office and station names. Most notably in the western part of the province – where Graaff-Reinet is situated – has largely retained its original place name identity without significant transformation.

Figure 1. Distribution of place name changes in the Eastern Cape, December 2023 (https://www.sagns.gov.za/GeographicNameLookupTool/).

On 29 August 2023, during a special session of the Dr. Beyers Naude Local Municipality, a proposal from the Eastern Cape Provincial Government’s Department of Sport, Recreation, Art, and Culture was introduced to the Council. The recommendation put forward suggested changing the names of four towns within the municipal area. This presentation marked a significant step in the process of potential place name modifications in this part of the province. The proposed name changes are: Graaff-Reinet to Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe or Fred Hufkie (however, family of the late Hufkie requested that the name be removed from the nomination list); Adendorp to Kwa Mseki Bishop Limba; Aberdeen to Camdeboo; and Nieu-Bethesda to Kwa Noheleni. The origin of the name Graaff-Reinet dates back to 1786 when the new district boundaries were finalized and named after the Dutch Governor, Cornelis Jacob van der Graaff and Reinet, the maiden name of his wife Cornelia. In turn, the person after which the town is proposed to be renamed is Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe. He was born in Graaff-Reinet on 5 December 1924 and was a political activist and founder of the Pan Africanist Congress (Burden, Citation2024). Considering Graaff-Reinet’s historical context and role in this part of the former Cape colony, and the contemporary significance in tourism, it is anticipated that there would be strong resistance to a name change. Despite the fact that understanding the dynamics of renaming places can provide insights into the cultural and political shifts within society at all scales, and shedding light on historical narratives and power relations (Mkhize & Naidoo, Citation2023), South African geography scholarship has largely neglected this research topic. Guyot and Seethal (Citation2007) suggested that geographers might examine the impacts of place name changes on local identities, historical interpretations, and broader societal changes. There was no more opportune time than the present to investigate the opinions of the town’s residents regarding the proposed name change.

This study explores whether Graaff-Reinet residents support the suggested name change and examines how their perspectives align with considerations of place identity, social cohesion, and place attachment, particularly at the initial stages of the renaming process. In South Africa, there is a lack of evidence regarding the utilization of scientific studies to assess residents’ opinions before a name change, making this study a pioneering endeavour in this context. The paper’s main argument is that if a survey indicates strong social cohesion across all demographic groups within the town, along with a predominant sense of identity, place attachment, and toponymic connection, then these findings can serve as a compelling argument either for or against the proposed name change.

2. Literature and conceptual context

2.1. Toponomy

Colonialism aimed to impose order and significance on non-European landscapes through the practice of place naming. Thus the historical context of colonial and apartheid toponymy, which affirmed white identity while suppressing indigenous history, is acknowledged (Ndletyana, Citation2012). Naming or renaming played a crucial role in the expansion of imperial control over both physical and human environments (Williamson, Citation2023). The connection between place names and issues of identity and power, particularly in plurilingual and multicultural countries, often introduces complexity into these processes (Andersson, Citation2020). Whether evolving naturally or being consciously bestowed, place names assume significance as signs, signals, and symbols within dynamic cultural landscapes. Over time, these names can acquire multiple meanings or be interpreted differently by various communities. Furthermore, they play a crucial role in establishing a sense of cultural and social continuity between the past and the present. For many residents, place names serve as mental maps imbued with codified knowledge, historical legacies, and symbolic representations (Savage, Citation2020). Place names can be regarded as one of the oldest living aspects of human cultural heritage, having been orally transmitted from generation to generation for hundreds (in some cases thousands) of years at their respective locations of origin. They hold a unique position in our cultural heritage by offering insights into both the places they describe and the individuals who bestowed these names. As such, they serve as valuable supplements to the history of settled areas, forming connections to the past. In essence, place names function as textual representations of the historic landscape (Helleland, Citation2012). The significance of a place name imbued with a sense of history and meaning lies in its role as a linguistic artefact and a toponym (Thornton, Citation1997). Such names offer valuable insights into the ways in which humans perceive and interact with the world.

Place naming is an administrative and political act and therefore ‘constitutes an expression of power’ (Belshaw, Citation2005, p. 9). Additionally, Radding and Western (Citation2010, p. 394) argue that

in different ways, linguistics and geography each observe that a name’s significance is connected to a society. According to lexical theory, a word is arbitrary: its sound and meaning have no intrinsic link, and its function is grammatical. Names, however, are special words… Toponyms, in turn, are special names, and in some cases, a toponym reveals that names reflect the experience of the people who use them.

They further argue that ‘[N]ames are given intentionally to impart a certain meaning. They can be the opposite of arbitrary. Yet, over time, people can fail to remember the original, specifically intended meaning and attribute other ones’ (Radding & Western, Citation2010, p. 396). As a place-name becomes opaque and the original meaning is lost over time, ‘the name comes to feel like a word, in that it feels like an arbitrary combination of sounds used to refer to a certain item or idea’ (Radding & Western, Citation2010, p. 396).

Toponymy was criticized as atheoretical, apolitical and uncritical until the toponymic turn in the latter half of the 1980s and early 1990s (Spocter, Citation2018). After a political transition, especially in a post-colonial and post-communist context, it is common for place names and street names to be changed as a way of recognizing and honouring the victims of atrocities and conflicts. Thus the practice of name changes is a significant aspect of transitional justice. In this process, the names of oppressive leaders from a previous regime are substituted with names that symbolize the values of the emerging new order (Swart, Citation2008). Changes in place names are inherent to historical shifts, reflecting the ebb and flow of political and cultural forces. These names, serving as identifiers of geographical landmarks and cultural identities, are particularly susceptible to alterations driven by political transitions, such as the rise and fall of Communism in Eastern Europe (Azaryahu, Citation1986). Instances of renaming, like those witnessed in Africa following the end of the colonialism (and apartheid in South Africa) are often spurred by shifts in dominant political ideologies (Chilala & Hang’ombe, Citation2020; Mbenzi, Citation2019). Similarly, in post-colonial contexts such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, initiatives to acknowledge and respect indigenous languages have resulted in the prominence of indigenous place names, reflecting the impact of changing cultural perspectives on the landscape of names (Kearns & Lewis, Citation2019; Kostanski, Citation2009; Shields, Citation2023).

2.2. Toponymic-and-place attachment

Toponymic attachment plays a crucial role in shaping an individual’s understanding of a location. It is also characterized as the emotional or symbolic bonding of individuals or communities to place names, and it encompasses both positive and negative connections. This phenomenon speaks to the way people form a deep-seated relationship with specific toponyms, influencing their understanding and perception of a place. The concept of sense of place encompasses three interconnected elements: place identity, place dependence, and place attachment (McKercher et al., Citation2015). Often conflated with image, identity refers to how various stakeholders, such as residents, tourists, and investors, perceive and experience a city (Gilboa et al., Citation2015, p. 50). This means that a city’s identity may differ from the image it presents to its audiences. The six dimensions, known as the P-dimensions, provide a comprehensive framework for understanding a city or small town’s image: (Presence: the international reputation of a city; Place: perceptions of the physical characteristics of cities; Potential: economic and educational opportunities; Pulse: urban lifestyle; People: the relationship between residents and outsiders; and Prerequisites: the perceived essential qualities of a city (Anholt, Citation2006).

Attachment can be deeply rooted in cultural, historical, or personal associations, contributing to the identity and sense of belonging people feel towards a certain location (Kostanski, Citation2016; Sancho Reinoso, Citation2022). Place names play a foundational role in fostering place attachment and shaping spatial identity (Kayster, Citation2024). The study of the etymology of place names is closely intertwined with the phenomenological understanding of place as any environmental locus in and through which individual or group actions, experiences, intentions, and meanings are drawn together spatially. Connecting places with individuals cultivates significant locales to which people develop attachments giving rise to the concept of place attachment (Sancho Reinoso, Citation2022).

The term identity is employed to describe both stable and enduring conditions as well as ongoing processes. What is encompassed by identity frequently undergoes changes over time, influenced by external circumstances and the prevailing mood and mindset of individuals or groups. It is important to note that the concept of identity for one generation may not necessarily be identical for the subsequent generation (Helleland, Citation2012). Place names play a significant role in fostering a sense of belonging to both a specific area and the social group residing within it. Whether individuals grow up and reside in rural or urban landscapes, they develop familiarity with their surroundings from an early age, forming emotional connections to these places (Helleland, Citation2012).

Place identity encompasses the emotional connection inherent in place attachment and is intertwined with the symbolic significance of place relationships. The development of place identity can influence communal expectations regarding activities and behaviours within specific locales (Kostanski, Citation2014). As a subjective and enigmatic social construct, place identity is rarely contemplated in individuals’ daily thoughts and communications. People typically only become cognizant of place identity when their sense of place is threatened (Proshansky, Citation1978). A toponym constitutes one of the vectors in the definition of the identity of a place and in a society characterized by a multiplicity of diverse political and cultural values, changes in place names can be a unifying or dividing catalyst.

The concept of sense of place revolves around the emotional relationship that individuals establish with specific locations. This emotional connection is intensified by both the physical characteristics of a place and the activities and meanings associated with it. The physical attributes not only contribute to the character of a particular setting, defining its nature, but also imbue it with significant meanings. The perception of the sense of place is shaped by individuals’ past experiences, backgrounds, memories, personalities, knowledge, culture, attitudes, motivations, and so on. Fundamentally, the sense of place emerges from the ongoing interaction between individuals and their living space (Relph, Citation1976; Shamai & Ilatov, Citation2005). Additionally, place attachment is commonly perceived as closely linked to time; specifically, the longer one resides in a particular area, the stronger the emotional connection to it tends to become (Rammile & Matamanda, Citation2022).

2.3. Social cohesion

Social cohesion refers to ‘the extent of connectedness and solidarity among groups in society. It identifies two main dimensions: the sense of belonging of a community and the relationships among members within the community itself’ (Manca, Citation2014, p. 6026). Measuring and understanding social cohesion will vary greatly depending the geographic scale of analysis (for example, from national to town level to neighbourhood level). However, drawing from the broad range of literature on social cohesion Fonseca et al. (Citation2019) identified three key perspectives for studying social cohesion: the community level, focusing on shared values and social bonds; the individual level, examining personal connections and participation; and the institutional level, considering factors like social behaviour and trust. Similar to discussions on social cohesion, it’s crucial to move beyond vague prescriptions and normative assertions in order to critically delve into the examination of social capital at the neighbourhood (or small town) level (Forrest & Kearns, Citation2001). The aim is to delineate various aspects of social cohesion and strong communities, demonstrating how the concept can be broken down for the creation of research tools such as structured or semi-structured questionnaires to investigate it further.

The characteristics of a strong community are summarized in (which also guided the formulation of questions in the survey – refer to the methodology section). Strong social ties promote trust, cooperation, and mutual support among residents, contributing to community resilience in the face of serious challenges such as economic downturns, natural disasters, and social disruptions. Additionally, social cohesion enhances residents’ quality of life by fostering a sense of belonging, inclusion, and connectedness, which are essential for individual well-being and community vitality.

Table 1. Characteristics of strong communities and related counter-indicators.

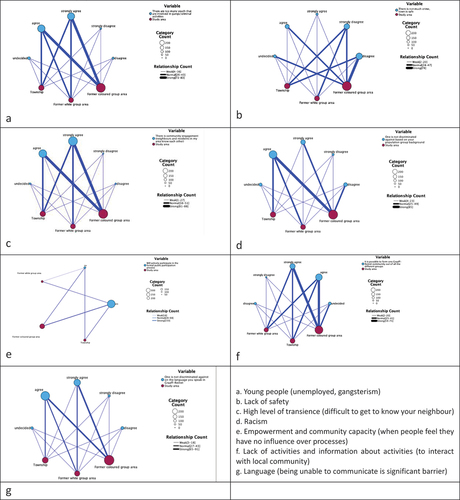

Despite its importance, social cohesion can be undermined by various challenges. A society characterized by lacking cohesion would exhibit social disorder and conflict, divergent moral values, significant social inequality, limited social interaction both between and within communities, and a diminished sense of place attachment (Forrest & Kearns, Citation2001). According to Bertotti et al. (Citation2012), there are specific obstacles to social cohesion, and they include the following: young people (unemployed, gangsterism); lack of safety; high level of transience (difficult to get to know your neighbour); racism; empowerment and community capacity (when people feel they have no influence over processes); lack of activities and information about activities (to interact with local community); language (being unable to communicate is significant barrier), and provision of free accessible community spaces. All these aspects were investigated in the survey.

3. Study area

According to Burden (Citation2024) numerous historical sources erroneously label Graaff-Reinet as the 4th oldest town in South Africa. The designation of ‘town’ (referring to the Western or colonial concept of a settlement, excluding indigenous communities for which the designation of ‘town’ did not apply at the time) traditionally implied the presence of a magistrate or magisterial district, yet many settlements in South Africa were established without this administrative feature. Therefore, a more precise characterization of Graaff-Reinet’s status would describe it as the 4th oldest magistrate or magisterial district in South Africa. Preceding Graaff-Reinet, only Cape Town, Stellenbosch, and Swellendam served as seats for a magistrate and court. Notably, several other settlements, including Paarl (originally Drakenstein), Tulbagh, Simon’s Town, and Malmesbury (originally Zwartland), were established prior to Graaff-Reinet, thereby placing it as the 8th oldest town (Burden, Citation2024).

Despite where it ranks in terms of historic origin the fact remains that Graaff-Reinet is deeply rooted in colonial history. On 19 July 1786, a proclamation delineating the boundaries of the newly established district was issued. This district was named after Dutch Governor Cornelis Jacob van der Graaff and Reinet, which was the maiden name of his wife Cornelia, initially spelled as ‘Graaffe-Rijnet’ (Burden, Citation2024). As is the case in the establishment of most small towns in the country the first church in the town was the Dutch Reformed Church, established in 1792 but destroyed by fire in 1799. In 1886 a fourth church was built and is still today in use and the historic landmark and focal point of the town (). The 1820 Settlers, who migrated from Great Britain and arrived at Algoa Bay over a span of approximately four years, faced challenges in establishing themselves as farmers on the eastern border of the Cape Colony. Within the first two decades, many of them abandoned their farms and relocated to neighbouring towns, where they pursued careers as merchants and artisans. A significant number settled in Graaff-Reinet, fundamentally altering the town’s landscape heralding a period of commercial advancement and unprecedented growth in building construction. Following the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), the colonial residents of Graaff-Reinet encountered immense challenges in resuming their pre-war way of life. Bitterness, animosity, and despair permeated the town. The outbreak of World War I further exacerbated divisions within the community of Graaff-Reinet. English-speaking residents lauded General Botha’s decision to enlist in the war effort and support the United Kingdom. In contrast, Afrikaans-speaking individuals, still harbouring resentment towards the British following the Anglo-Boer War, vehemently opposed participation in the conflict (Burden, Citation2024). The year 1948 marked a significant turning point in South African history with the National Party’s election victory, leading to profound changes in government and politics that impacted South Africans for decades. The enactment of the Group Areas Act of 1950 formalized and enforced mass forced removals, notably affecting the coloured community in Graaff-Reinet, with the first 50 families relocated in 1954 to Kroonvale (Kayster, Citation2024). However, the area known as Sunnyside was established in 1940 before the group areas act when 46 houses were built for coloured residents (). While black residents largely resided in a township named Umasizakhe (the township only received its name in the 1980s) (), they faced the emotional toll of seeing their coloured neighbours forcibly separated, yet remained resiliently loyal to Graaff-Reinet despite apartheid’s injustices (Burden, Citation2024). The historical part of the town () was earmarked by apartheid legislation for white occupancy only.

Figure 2. The fourth church in Graaff-Reinet, dating to 1886, the gothic revival styled NG Church based on the lines of Salisbury Cathedral in England (photo: Author, 2023).

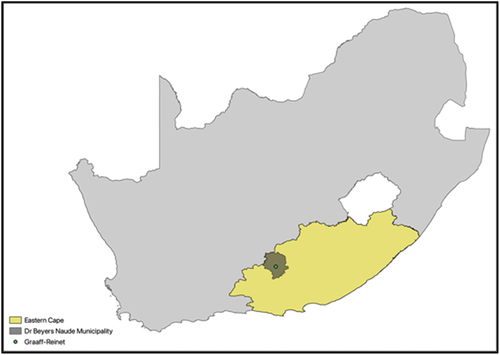

In a post-apartheid context the town is located in the Eastern Cape Province (). In an effort to address the historical marginalization of the Khoikhoi people, the Cacadu District was renamed the Sarah Baartman District in 2015, in honour of a Khoikhoi woman (1789‐1815) who tragically experienced exploitation through performing in London freak shows and posthumously being exhibited until 1974 (Drummond, Citation2018). As the largest of the eight districts in the Eastern Cape, it encompasses 34% of the province’s land area, spanning 58,243 square kilometres – larger than several small countries such as the Netherlands. The Sarah Baartman District previously comprised nine local municipalities, but in 2016, three municipalities (Baviaans, Camdeboo, and Ikwezi) were amalgamated into a single entity, the Dr Beyers Naudé Local Municipality (Drummond, Citation2018). Named after the prominent Afrikaner clergyman and anti-apartheid activist Beyers Naudé, the municipality’s administrative hub is located in Graaff-Reinet. The decision to merge these municipalities was made by the Municipal Demarcation Board in 2015 and was widely perceived as gerrymandering, attributed to the declining support for the African National Congress (ANC) in the region. Presently, the municipality is governed by a slim ANC majority, achieved through a coalition with a smaller party.

Figure 6. Study area (Light, Citation2023b, p. 5).

Located in the heart of the expansive geographical region called Great Karoo, Graaff-Reinet experiences the challenges of a semi-desert climate with scarce rainfall. Between 2015 and 2021, the town experienced an unprecedented drought, the severity of which had not been witnessed in recent memory. In response to this crisis, the shared goal of addressing the drought, coupled with effective and trusted leadership, facilitated collaboration between a local community forum and the Dr Beyers Naude Municipality (Light, Citation2023a). Renowned for its rich history, Graaff-Reinet boasts more than 220 heritage sites and is encompassed by the Camdeboo National Park and agricultural landscapes. The town’s economy thrives primarily on agriculture and tourism, while its urban structure remains significantly shaped by the apartheid-era Group Areas Act.

4. Methodology

The research design employed a quantitative approach, utilizing a representative sample survey with stratified random sampling to ensure a diverse representation of the population. Stratified random sampling were employed. This sampling method is usually followed in diverse population groups (such as income, racial, language, etc.). The population (Graaff-Reinet households) was divided into three subgroups (strata), and samples were randomly selected from each stratum (). The strata for the sample frame were the three previous Group Areas Act areas (the apartheid spatial imprint – dividing the population into different racial groups, mainly black, white and coloured – of the town): Graaff-Reinet (inclusive of Spandauville) which represents the former white group areas, the township (uMasizakhe), and the former coloured group areas (Kroonvale and Asherville and their respective sub areas). Data on the number of zoned residential erven in each of strata were counted from the 2023 municipal zoning map. Erven per definition was thus considered representative of a household/erf. By utilizing the physical count of residential erven, which amounted to 7,748 as indicated on the municipal zoning map the sample size of 367 interviews was determined to achieve a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error, providing statistically reliable insights into the sentiments and opinions of the broader population. A sample calculator was used to determine the size of the sample - https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html?type=1&cl=95&ci=5&pp=50&ps=7748&x=Calculate.

Table 2. Sample size distribution according to zoned residential erven.

A structured questionnaire was designed to gather data on three aspects. First, background demographics and personal information were collected, including age, gender, home language, length of residence in Graaff-Reinet, employment status, highest educational qualification, number of individuals living on the property, frequency of interaction with residents from diverse language or cultural backgrounds, and involvement in community groups. Population group was also noted by the fieldworkers. Second, questions were focused on the proposed name change and its process. Participants were asked about their awareness of the proposed name change, how they were informed about it, whether they agreed with the proposal and reasons for their answers, their knowledge about the current name’s origin and about Robert Sobukwe, and whether they found the current name offensive or associated it with any particular connotation. The necessity of changing town names to address colonial and apartheid legacies was also explored. Additionally, participants were asked if they had signed a petition against the name change, how they intended to participate in the public consultation process, and their perceptions of the fairness of that process. Third, the questionnaire included Likert-type scale questions assessing the value participants placed on various aspects of Graaff-Reinet, such as the community, historic landmarks, natural scenery, and feelings of belonging – these relate to issues of place attachment. Opinions on the town as a whole were also sought, covering topics like social cohesion and community strength among residents from different backgrounds, the performance of the local municipality, employment and crime conditions, and the prevalence of racism in the town.

The interviews were carried out by an independent research consultancy that hired university students to conduct the interviews. The diverse team of fieldworkers, reflected the town’s population dynamics and language demographics. There were eight trained fieldworkers involved in the study. Three conducted interviews in the township: one black male PhD geography candidate, a black female honours geography student, and a black male undergraduate economics student. All three were fluent in English and isiXhosa, with one also fluent in Afrikaans. Two white female honours geography students conducted interviews in the former white group area of the town. In the former coloured group areas, interviews were conducted by four honours geography students: two white males, one coloured male, and one coloured female. All four were fluent in Afrikaans and English.

The fieldwork took place between December 13 and 16 December 2023, strategically timed to maximize respondent availability. Data analysis was performed using SPSS. The study’s methodology aligns with the cornerstone principle in social science, emphasizing the importance of a probability-based sampling strategy for reliable statistical deductions. The fieldworkers visited the three strata sites, starting each day at a randomly selected point from which every 21st property served as sample point. In cases where there were no one present or the residents were not willing to take part then any of the surrounding properties were sampled as substitute. Additionally, in-house sampling were employed as far as possible using the ‘who’s birthday is next’ strategy to determine which individual in the household aged 18 and older will participate in the survey. If this failed then an adult member from the household who was willing, was interviewed This approach aimed to minimize bias in participant selection. It was not deemed necessary for this study to record the response rate (i.e. capturing information on refusals) because respondents were eager to participate in the survey and the survey is solely on analysing the responses received and not about measuring the methods employed.

5. South Africa’s place name process

By international standards, the pace of place name changes in South Africa was comparatively gradual. The initial reluctance of the ANC government under Mandela as president to implement widespread name changes can be attributed, in part, to the peaceful transition in South Africa, facilitated through compromise and negotiated settlements. Fifteen years into democracy, some scholars argued that, in practice, the majority of changes made by then were more corrective than assertive of the new political reality (E. Jenkins, Citation2009; N. Swanepoel, Citation2009), a trend that has persisted to the present day. In a map analysis conducted by E. R. Jenkins (Citation2017), the unpublished list of geographical names registered by the South African Geographical Names Council between 2000 and 2014 was scrutinized. The study revealed a notable increase in names from African languages; however, the registration of new names and the alteration of existing ones remained at a moderate level. However, it was not merely the act of renaming, but rather the overwhelming number of changes coupled with the insensitivity in the selection of names that attested to a shift in attitude by the authorities. This, in turn, provoked anger and protests across various sectors of society (Lubbe, Citation2019). As a multi-disciplinary theme scholarly investigation in South Africa into aspects of place name changes came from public management and anthropology. Renaming of streets appear to be the most investigated toponym type of study (Adebanwi, Citation2017; De Villiers & Kesselring, Citation2014; Erlank, Citation2017; Goodrich & Bombardella, Citation2012; Ndletyana, Citation2012; N. J. Swanepoel, Citation2012).

Public participation encompasses any process that actively involves the public in decision-making, ensuring thorough consideration of public input in the decision-making process. The South African Constitution mandates a significant role for the state in public participation, as all provincial legislatures are required to facilitate public engagement, as outlined in Chapter 10 of the Constitution of South Africa 1996. The creation of SANGC was driven by the goal of ensuring that name changes align with broader objectives such as nation-building, transformation, and consultation. In theory, these objectives closely correspond to the goals of transitional justice (Swart, Citation2008). The SAGNC is a consultative committee appointed by the national Minister of Arts and Culture. The ultimate authority to make final decisions on name changes lies with the Ministry alone. The SAGNC is tasked with examining incorrectly spelled names, ‘corrupted’ names, and proposed changes to the names of towns and cities. In 2003, the SAGNC underwent decentralization to the provincial sphere. While the SAGNC is mandated to facilitate name changes, the proposals for these changes must originate from the community, although they may be influenced significantly by community leaders (Guyot & Seethal, Citation2007). According to South African Geographical Names Council’s (Citation2002, p. 4) (within the ambit of the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture) Handbook on Geographical Names:

(a) A Provincial Geographic Name Committee (PGNC) is responsible for advising local authorities and working with them to ensure that they apply the principles of the South African Geographic Names Council (SAGNC) to the names under their jurisdiction.

(b) A PGNC makes recommendations to the SAGNC on the names of geographical features that fall within its provincial boundaries. It should do preparatory work for the submission of names to the SAGNC, and is responsible for seeing to it that local communities and other stakeholders are adequately consulted.

(c) A PGNC liaises with the SAGNC on promoting research and ensuring that unrecorded names are collected.

Although numerous place name changes end up in court, the example of Louis Trichardt exemplifies the importance of public participation best (E. Jenkins, Citation2009; Musitha, Citation2016). It remains however undeniable that even after consultations have occurred and panels of experts have provided their advice, political decisions will ultimately need to be made. The study of Mudau (Citation2009) also warns that not abiding by the rules of SAGNC, results in the polarization of communities, whereas the study Sepota and Madadzhe (Citation2007) showed that it is nevertheless evident that such problems can be prevented if the authorities conduct proper consultations and avoid using personal names. According to Phalane (Citation2007) it is crucial for municipalities to be attentive to three procedural steps when initiating a name change. These steps include providing ample notice regarding the timing of public meetings, engaging with as many communities and stakeholders within the municipality as possible, and affording sufficient time for public and stakeholder debates before recommending name changes to the Minister. Neglecting these steps may compel municipalities to revisit the planning stage and incur the costs associated with protracted litigation (Phalane, Citation2007), as the Louis Trichardt case clearly showed. The process of renaming places is expected to persist as South Africa undergoes ongoing redefinition.

6. Survey results and discussion

6.1. Respondent profile

Out of the 367 respondents interviewed, 18.8% identified as white, 27.2% as black, and 54% as coloured and slightly more female respondents (50.7%) than male respondents (49.3%) participated in the survey. Both of these demographic variables provide a representative reflection of the town’s population and gender demographics. Afrikaans is the predominant language in the town (72.1%) followed by isiXhosa (21.1%) an English 6.6%. Just less than half (48.1%) of respondents only have a secondary school education, 22% primary or no schooling and the remainder have some form of post school qualification (30%). Regarding employment status, 46.4% reported having some form of employment (full-time or part-time), while the majority (53.6%) indicated no form of employment (unemployed, retired, or other categories such as students and individuals with disabilities). The majority of respondents’ parents were born in Graaff-Reinet (71.9%), and a significant percentage of these parents still reside in the town (49.3%) – though many have since passed away. Impressively, the average number of years that respondents have been living in the town is 36.5 years (with a median of 36 years). Three quarters of respondents have been residing in Graaff-Reinet for more than 20 years, indicative of a stable and long-standing community.

6.2. Knowledge and opinions on the proposed name change

The questionnaire survey commenced by querying respondents about their awareness of a proposed name change, revealing that more than three-quarters (77.7%) were indeed aware of the proposal. Among the 82 respondents who were unaware of the name change, 48.8% were from the township, 42.7% from the former coloured group areas, and 8.5% from the former white areas ().

Table 3. Opinion on name change according to three strata.

Anticipating resistance to toponymic changes, particularly from South Africa’s white community, is evident in other case studies (Kabinde Machate et al., Citation2022; Lubbe, Citation2019). In contrast to findings in studies on name changes in Tshwane (Kabinde Machate et al., Citation2022; Njomane, Citation2009), where residents’ perceptions in the City of Tshwane are still influenced by race – whites perceiving no need for renaming, while blacks believe the process is necessary and long overdue – this dynamic appears not to be the case in Graaff-Reinet. A significant majority of respondents (83.6%) expressed the opinion that the name should not change. Even when cross-tabulated with the three sampling strata, it becomes apparent that, contrary to expectations, a majority in the township wishes for the name to remain. Black respondents were the most undecided (13%) and the highest percentage who said that the name should change, albeit not a majority (32%). Interesting to note, Kayster (Citation2024, p. 42) stated that since the 1960s many Xhosa-speaking residents elected ‘to use the word “Irafhu”’, a phonetic rendition of the word Graaff-Reinet.

Public outcry to place name changes in South Africa predominantly revolves around issues of identity and history. These perspectives unavoidably mirror South Africa’s racial divisions. Detractors argued that renaming amounted to an assault on their identity, interpreting it as an attempt to erase their presence from South African history. Advocates, on the other hand, embraced renaming as a means of reaffirming their identity and integrating their historically marginalized narratives into the public record (Ndletyana, Citation2012). Why should a place name not change? Frequently, the argument against changing the names of cities, roads, rivers, or geographic regions in South Africa revolves around the perceived cost involved. Critics often juxtapose the expenses associated with name changes against the potential for building houses or feeding the homeless. While this perspective is emotive and may be factually accurate, it tends to overlook the broader context and underlying significance of the renaming process (Buckland, Citation2007). Categorized into three strata areas regarding the reasons why the name should not change, common themes emerging from the responses include familiarity with the current name, its long-standing historical significance, and the necessity to redirect focus towards service delivery. The most poignant of the statements were from a respondents from an unemployed male from the former coloured group areas in the age category 45–64 who has been living for 57 years in Graaff-Reinet, who said ‘If you name a child and then change the name it is someone else’. Other selected main theme-related quotes from respondents were:

From the former coloured group areas:

‘We grow with the town and the history of the town’ [translated from Afrikaans]

‘It is part of our history therefore should not change’

‘Graaf-Reinet’s name has a history and we don’t want to lose the history’ [translated from Afrikaans]

‘I grew up with the name and want my descendants to grow up under the same name as me’ [translated from Afrikaans]

‘It is a historic town and all the places are connected to the name’ [translated from Afrikaans]

From the township:

‘The name we have represents us as it currently is’

‘The history of the town revolves around the current name’

Since it is an old town it has identified the name as a significant trademark, no need to change

From the former white group areas:

‘You do not have to change history’

‘The name is historical not political’

‘You cannot change the past i.e. a place, person’s name such as town does not change’ [translated from Afrikaans]

‘It is not offence and is historical in nature’

‘Everyone knows the name’ [translated from Afrikaans]

Overall, respondents highlight the town’s rich history, the economic importance of its current brand, and the potential risks associated with rebranding efforts. The unified stance against the name change reflects a shared commitment to preserving Graaff-Reinet’s identity and heritage.

6.3. Awareness about historic-and-proposed name

Three-quarters of the respondents attempted to explain the origin of the town’s name. The majority (69.8%) simply stated that the town is named after a man (Graaff) and his wife (Reinet). However, there was a common misconception, with almost all mistaking ‘Reinet’ as a first name rather than a surname. Another portion (16.7%) correctly identified that the town is named after a Governor and his wife, although the same misconception about ‘Reinet’ persisted. A minority (13.5%) provided alternative origins, such as the first people who lived in Graaff-Reinet, the first mayor, the first dominee, two settlers/colonialists, Afrikaners, white people, and even Rupert’s ancestors. A similar question was asked to assess how much residents know about the person after whom the town is proposed to be named. Of the 251 respondents who tried to identify who Sobukwe was 29.9% associated him with the PAC (either as a prominent figure, founder, or member); 32.7% associated him with the freedom struggle, seeing him as a freedom fighter or activist; and 24.6% indicated that he had some roots in Graaff-Reinet (i.e. that he was born there, lived there, worked there).

6.4. Opinions on the name Graaff-Reinet

The SAGNC Handbook specifies two valid reasons for changing an existing South African place name: (1) objectionable replacement of an existing name that some wish to restore; and (2) linguistic modifications that may be deemed offensive (South African Geographical Names Council, Citation2002, p. 6). Concerning the proposed renaming of Graaff-Reinet to Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, it aligns with two categories cautioned against in the Handbook – names being excessively long or awkwardly compounded, and names solely composed of a personal name without an additional generic component. The reason for the application to change the name of Graaff-Reinet is not known because the Geographical Names Committee of the Eastern Cape Province has not made it available yet (Burden, Citation2024).

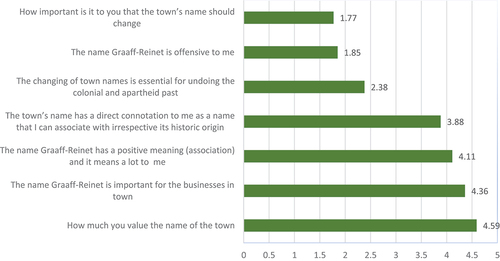

Scholars often delve into the ways in which toponyms convey meaning and facilitate the transmission of cultural and historical information. The phrase ‘we are known as Graaff-Reineters’ was commonly used by respondents in the survey. Place names can encapsulate narratives, traditions, and memories, serving as linguistic markers that embody the collective identity of a community (Helleland, Citation2012). These names can also carry implicit meanings, reflecting the geography or cultural significance of a place (Kayster, Citation2024). Place names may be used as symbols to mobilize and develop a political and historical consciousness of common identity (Guyot & Seethal, Citation2007). shows the mean scores (ranging from 1= not important/strongly disagree to 5 = very important/strongly agree) for a range of statements about the name Graaff-Reinet. Toponymic attachment refers to the positive or negative connections individuals and groups establish with a place name. Building upon the principles of place attachment, Kostanski’s (Citation2009) theory explores various avenues for research within the geographical domain. It delves into subdomains such as toponymic identity, which involves emotional associations, and toponymic dependence, which relates to functional associations. The findings clearly indicate a significant toponymic identity associated with the town’s name, particularly evident in the reasons against its change and the level of value attributed to it. Additionally, there exists a toponymic dependence, notably observed in its significance to the town’s business sector. There also appears to be less emphasis on the functional significance of altering place names as a post-apartheid project.

6.5. Strength of place identity

Some studies have made attempts to measure place identity and attachment with a single question (Hamann, Citation2019; Peng et al., Citation2020). In the survey, Pretty et al. (Citation2003) statement which they asked for residents’ responses to a statement to test their identification with their residential community was used, namely: ‘I would really rather live in a different town. This one is not the place for me’. They argued that one’s town is not the place ‘for me’ is to suggest that one’s town is not constituted as part of one’s self-identity. The evidence is overwhelmingly indicating that there is a very strong sense of community identity and place attachment with 90.3% who said that they disagree with the statement, 6.6% agreed (low community identity) and 3.0% were undecided.

6.6. Value, identify and place attachment

Characteristics of place attachment are diverse. An emotional bond that individuals develop to a specific place based on personal experiences, memories, and feelings associated with it together with a feeling of belongingness and identity, where individuals feel a deep sense of rootedness and connection to the place are pertinent to this study. Gamma was used in SPSS to determine the statistical correlation between the ‘value that respondents attach to the name of the town’ and a number of other variables which can be considered important characteristics of sense of place and place attachment (all measured on ordinal scale) ().

Table 4. Correlation between the ‘value that respondents attach to the name of the town’ and selected sense of place-related variables.

A relative importance index (RII) was calculated for the social and environmental values that respondents attach to Graaff-Reinet. The importance of each of the value statements were then ranked from most to least importance (). The name of the town ranked third out of the eight value statements. It must be noted that all the value statements scored very high index values which affirms the fact that the respondents have a strong bond with the town and its people and name.

Table 5. Relative importance index for social and environmental issues.

6.7. Name change and social cohesion

The issue of name changes as a means of promoting social cohesion has elicited varied arguments in both the literature and society in South Africa. Scholars contend that these changes reflect the evolving character of governance on both a national and normative level. Within society, assertions regarding history, even histories considered incompatible with the collective national democratic ideal, find a place across South Africa’s diverse population spectrum. Frequently, there is significant resistance from communities either indifferent to the need for altering older names or deliberately intent on preserving them for posterity or as a form of national adherence (Abrahams, Citation2021, p. 25).

Except for the aspect of ‘provision of free accessible community spaces’, the eight specific obstacles to social cohesion identified by Bertotti et al. (Citation2012) earlier in the paper were addressed in the questionnaire survey. Without exception, a robust relationship exists between the three study area strata and the various obstacles to social cohesion, pointing to general agreement in terms of opinions on these aspects ().

According to Kayster (Citation2024, p. 241) the Graaff-Reinet example ‘demonstrates that the slow pace, and limited extent, of renaming in post-apartheid society contradicts the notion that leadership, intent on change, should be actively engaged in the rapid manifestation of change through methods such as toponymy’ and that the ‘presence of political interference in name changing processes in Graaff-Reinet cannot be repudiated, as the entire process is fundamentally a political activity aimed at political gain’.

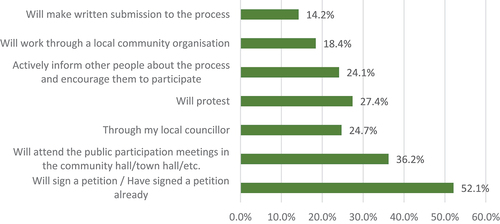

6.8. Public’s intended participation in the process

The first stakeholders’ consultation session (public meeting) occurred on 22 November 2023, drawing participants from diverse backgrounds, many dressed in green T-shirts with the slogan ‘Hands off Graaff Reinet’. The so-called green movement also arranged for a number of street protests (). A review of media reporting on place name changes in South Africa indicates that, while numerous communities have utilized petitions to express their opinions on renaming a place, Typically, retrospective studies are conducted in such cases. However, it’s essential to note that while petitions may have some advantages (for example petitions provide a platform for individuals to collectively express their opinions on a particular issue and petitions create a documented record of public sentiment at a specific point in time, etc.), they also have limitations. They may not capture the full diversity of opinions within a community, and the number of signatures alone doesn’t necessarily reflect the depth or nuance of those opinions. In the case of Grahamstown whose name changed to Makhanda, the Keep Grahamstown Grahamstown (KGG) movement collected over 6000 signatures of objectors, yet the name was changed (Maclennan, Citation2018, n.p.n). Additionally, the effectiveness of a petition depends on how well it is organized, promoted, and the context in which it is presented. In the case of place name changes, combining petition efforts with other methods, such as scientific surveys or community forums, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of public sentiment and contribute to a more inclusive decision-making process. At the time of the report writing there were a number of petitions being facilitated by a number of different lobby groups in Graaff-Reinet: The Democratic Alliance collected 500 signatories as at 5 December 2023; Singaphezulu Ngabeyis NPC collected as at 11 December 2023, 4 341 online and 2106 door to door; and the Graaff-Reinet Residents and Ratepayers Association as at 14 December 2023 collected 1 317 signatories.

Figure 9. Street protest against the proposed name change (Photo courtesy of L. Hoffman, December 2023).

A majority of respondents (76.7%) expressed their intention to actively participate in the formal process of public participation in various ways (). This indicates a notable level of engagement and interest among the surveyed population regarding the proposed name change and the associated public participation process.

For a South African place name change application, the applicant must fulfil three criteria outlined by the South African Geographical Names Council (SAGNC) Handbook (Citation2002). At the start of the Graaff-Reinet process, despite numerous written and oral requests, the application was not shared with other stakeholders, leaving uncertainty about meeting these requirements (Burden, Citation2024). It is evident that the contestation of the name will play itself out in the courts in the coming year(s), similar to the cases of Grahamstown, Louis Trichardt, Pretoria, to name but a few.

7. Conclusion

The Graaff-Reinet case stands out as exceptional in terms of community response to place name changes in South Africa. Unlike other cities marked by clear racial divisions in opinions, Graaff-Reinet demonstrates a notable cross-race resistance to name changes. In Graaff-Reinet, it was observed that resistance to altering a toponym can act as a unifying force, with the majority expressing the view that it should remain unchanged. With reference to strong characteristics of Bertotti et al. (Citation2012) study – refer back to – the survey findings empathically presents a strong community scenario in Graaff-Reinet. Although spatial racial divides exist does it appear not to be the same for interrelations. Shared values about the town, its people and history, its place in the broader geographical region and its characteristic features, physical and man-made built structures are evident from the data. Residents feel empowered and there is capacity to participate in local associations and organizations. It is also a town where residents generally feel safe (refer to ).

Overall, respondents overwhelmingly support the preservation of the historical, cultural, and linguistic heritage embedded in the town’s geographical name. The study underscores the significant role toponyms play in defining a place’s identity. In other words toponymic identity and attachment do exist and is reinforced by connection to community. The findings affirms that Graaff-Reinet’s name has evolved in meaning which has been fostered by strong connections to the town they call home. Few respondents today associate the town Graaff-Reinet with its colonial origins. It has taken on a new meaning, and the toponym is now close to opaque. Once a name becomes opaque,

we frequently reassign meaning to it via a folk etymology because we generally want to link form and meaning, especially in terms of names that we care about. We add a meaning, which may have nothing to do with the name’s original sign (Radding & Western, Citation2010, p. 397)

It is clear from the empirical evidence collected in the survey that the place name Graaff-Reinet, once relatively innocuous and neutral, has evolved in meaning and been subverted in the modern era. It is recognized that toponyms serve both a utilitarian (denotative) and a symbolic (connotative) function. However, despite their initial intent, toponyms gradually become more closely linked to the geographical space they designate than to the commemoration of past heroes or events (Steenkamp, Citation2015). The (re)naming of geographical spaces should not simply be a matter of political correctness, but rather used as a vital tool to achieve fair cultural and political representation, while at the same time preventing the loss of social groups and historical identities, especially in the wake of regime change (Cantile, Citation2016; Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2010).

For ‘Graaff-Reineters’, the names of places hold a significance that goes beyond mere sentiments and culture; they are repositories of cherished memories. A name serves as a reference point encompassing a multitude of associations, with two particularly noteworthy aspects. Firstly, it encapsulates the local history of a place, providing a lens through which the community perceives its identity. Secondly, it plays a pivotal role in the branding and packaging of the town, holding particular importance for economic drivers, notably tourism. The name, in this context, becomes a crucial factor in shaping perceptions and attracting visitors, contributing significantly to the town’s economic landscape.

Place-names constitute a crucial aspect of our geographical and cultural milieu. They serve to identify various geographical entities and embody irreplaceable cultural values that hold vital significance for people’s sense of well-being and belonging. Given their major social importance, society bears the responsibility of preserving the place-name heritage. This involves ensuring that place-name planning is conducted in a manner that preserves the functionality of the place-name inventory and safeguards the cultural heritage, especially in the face of rapid societal changes (Helleland, Citation2002). The Ninth UN Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names acknowledged that toponyms are, indeed, integral components of the intangible cultural heritage. From the study findings it is evident that overall a large percentage of respondents were in agreement with the principle of the SAGNC’s Handbook that ‘[G]eographical names are part of the historical, cultural and linguistic heritage of the nation, which it is more desirable to preserve than destroy’ (South African Geographical Names Council, Citation2002, p. 7).

The study findings confirms Kayster’s (Citation2024, pp. 40–241) observations that:

[M]any residents expressed their desire to retain the name: a sentiment which also breached the colour divide. For these residents, the name Graaff-Reinet had long since rid itself of negative colonial associations and spoke to their particular identity and the resulting futility, and apparent frivolity, of the exercise, motivated their opposition to a name-change … The name Graaff-Reinet has thus become a new repository of the past which both conveys the desire of the residents to assert their identity and serves as an indicator of how Graaff-Reinetters perceive themselves, and their history, in the present. The current meaning and association that residents have adopted, with respect to the name of the town, has therefore adapted and changed from the time of establishment and naming of the town, to the present. This meaning, and association, is primarily positive as residents elect not to recall past humiliations, especially under apartheid, but instead choose to subconsciously substitute negative memories with more recent and meaningful ones.

In conclusion, the study recommends a thoughtful approach to toponymic changes, considering their impact on identity, community unity, and economic dynamics. A nuanced approach, considering both historical context and community sentiments (through scientific based studies such as the Graaff-Reinet example), to guide decisions on potential place name modifications is recommended. Kayster’s proposal (Citation2024, p. 266) suggesting that Graaff-Reinet be both Graaff-Reinet/Irafhu is perhaps not far-fetched.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrahams, C. (2021). Social cohesion as imposition of national identity. In L. Fortaillier (Ed.), Discussing social cohesion in South Africa (pp. 24–30). IFAS.

- Adebanwi, W. (2017). Colouring “rainbow” streets: The struggle for toponymic multiracialism in urban post-apartheid South Africa. In R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, & M. Azaryahu (Eds.), The political life of urban streetscapes: Naming, politics and place (pp. 218–240). Taylor & Francis.

- Alderman, D. H. (2008). Place, naming and the interpretation of the cultural landscapes. In B. Graham (Ed.), The Routledge research companion to heritage and identity (pp. 195–213). Routledge.

- Andersson, D. (2020). Indigenous place-names in (post)colonial contexts: The case of Ubmeje in Northern Sweden. Scandinavian Studies, 92(1), 104–126. https://doi.org/10.3368/sca.92.1.0104

- Anholt, S. (2006). The Anholt-GMI city brands index: How the world sees the world’s cities. Place Branding, 2, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990042

- Azaryahu, M. (1986). Street names and political identity: The case of East Berlin. Journal of Contemporary History, 21(4), 581–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200948602100405

- Belshaw, K. J. (2005, December). Decolonising the land-naming and reclaiming space. Quality Planning. https://www.qualityplanning.org.nz/sites/default/files/Decolonising%20the%20Land.pdf

- Berg, L. D., & Kearns, R. A. (1996). Naming as norming: ‘race’, gender, and the identity politics of naming places in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14(1), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1068/d140099

- Bertotti, M., Adams-Eaton, F., Sheridan, K., & Renton, A. M. (2012). Key barriers to community cohesion: Views from residents of 20 London deprived neighbourhoods. Geo Journal, 77(2), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-009-9326-1

- Buckland, M. (2007). Name changes: ‘cost argument’ is nonsense. https://thoughtleader.co.za/name-changes-cost-argument-is-nonsense/

- Burden, M. (2024). The name change process of Graaff-Reinet: Background report on the history and cultural history of Graaff-Reinet [ Unpublished report]. Stellenbosch University.

- Cantile, A. (2016). Place names as intangible cultural heritage: Potential and limits. In A. Cantile & H. Kerfoot (Eds.). Place names as intangible cultural heritage-Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium Firenze 26th - 27th March 2015 (pp. 11–16). IMGI, Firenze.

- Chauke, M. T. (2015). Name changes in South Africa: An indigenous flavour. Anthropologist, 19(1), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2015.11891662

- Chilala, C., & Hang’ombe, K. (2020). Eponymic place names in Zambia: A critical toponymies perspective. Journal of Law and Social Sciences, 3(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.53974/unza.jlss.3.1.442

- De Villiers, I., & Kesselring, R. (2014). What’s in a name? Street names and the fine line between silencing and predicating history. Tsantsa, 19, 150–162.

- Drummond, F. (2018). Cultural clusters as a local economic development strategy in rural, small town areas: The Sarah Baartman District in the Eastern Cape of South Africa [ Master of Commerce thesis]. Rhodes University.

- Dube, L. (2018). Naming and renaming of the streets and avenues of Bulawayo: A statement to the vanquished by the victors? Nomina Africana: Journal of African Onomastics, 32(2), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.2989/NA.2018.32.2.1.1325

- Erlank, N. (2017). From main reef to Albertina Sisulu Road: The signposted heroine and the politics of memory. The Public Historian, 39(2), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2017.39.2.31

- Fonseca, X., Lukosch, S., & Brazier, F. (2019). Social cohesion revisited: A new definition and how to characterize it. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 32(2), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1497480

- Forrest, R., & Kearns, A. (2001). Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Studies, 38(12), 2125–2143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120087081

- Gilboa, S., Jaffe, E. D., Vianelli, D., Pastore, A., & Herstein, R. (2015). A summated rating scale for measuring city image. Cities, 44, 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.01.002

- Goodrich, A., & Bombardella, P. (2012). Street name-changes, abjection and private toponymy in Potchefstroom, South Africa. Anthropology Southern Africa, 35(1–2), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2012.11500020

- Guyot, S., & Seethal, C. (2007). Identity of place, places of identities, change of place names in post-apartheid South Africa. South African Geographical Journal, 89(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2007.9713873

- Hamann, C. (2019). Social attitudes in Gauteng. In R. Ballard (Ed.), Social cohesion in Gauteng (pp. 44–113). Gauteng City-Region Observatory GCRO.

- Helleland, B. (2002). The social and cultural value of place names. Eighth United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names, Berlin. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/geoinfo/ungegn/docs/8th-uncsgn-docs/crp/8th_UNCSGN_econf.94_crp.106.pdf

- Helleland, B. (2012). Place names and identities. Oslo Studies in Language, 4(2), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.5617/osla.313

- Irvine, P. M., Memela, S., Dlongolo, Z., & Kepe, T. (2021). Navigating community and place through colloquial street names in Fingo Village, Makhanda (Grahamstown). Urban Forum, 32(3), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-021-09416-w

- Jenkins, E. (2009). Attitudes towards geographical renaming in South Africa. In G. Teulié & M. Joseph-Vilain (Eds.), Healing South African wounds. (pp. 307–332). Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée.

- Jenkins, E. R. (2017). Some aspects of South African geographical names registered between 2000 and 2014. South African Geographical Journal, 99(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2015.1052844

- Kabinde Machate, M., Madoda Cekiso, M., & Mandende, P. (2022). Analysing City of Tshwane residents’ perceptions of street renaming. Nomina Africana: Journal of African Onomastics, 36(2), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.2989/NA.2022.36.2.2.1368

- Kayster, A. F. (2024). The complexities of heritage production in a South African Community from the 1900s to the present: Graaff-Reinet, a case study [ PhD dissertation in History]. Stellenbosch University.

- Kearns, R. A., & Lewis, N. (2019). City renaming as brand promotion: Exploring neoliberal projects and community resistance in New Zealand. Urban Geography, 40(6), 870–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1472445

- Kostanski, L. (2009). Toponymic books and the representation of indigenous identities. In H. Koch & L. Hercus (Eds.), Aboriginal placenames: Naming and re-naming the Australian landscape. Aboriginal history monographs (pp. 175–187). ANU Epress.

- Kostanski, L. (2014). Duel-names: How toponyms (placenames) can represent hegemonic histories and alternative narratives. In I. D. Clark, L. Hercus. & L. Kostanski (Eds.), Indigenous and minority placenames. Australian and international perspectives (pp. 273–292). ANU Press.

- Kostanski, L. (2016). Toponymic attachment. In C. Hough (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of names and naming. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199656431.013.42

- Light, R. (2023a). Collaborative governance, social capital and drought: A case study of a collaborative governance regime in Graaff-Reinet. In R. Donaldson (Ed.), Socio-spatial small town dynamics in South Africa (pp. 79–106). Springer.

- Light, R. (2023b). Collaborative governance, social capital, and drought: A case study of Graaff-Reinet. thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts, geography and environmental studies. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University.

- Lubbe, J. (2019, September 18–20). The role of politics, culture and linguistic factors in the naming and re-naming of street and suburb names a case study. In C. R. Loth (Ed.). Recognition, regulation, revitalisation place names and indigenous languages-Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Place Names 2019 Jointly organised by the Joint IGU/ICS Commission on Toponymy and the UFS Clarens (pp. 181–195). South Africa. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/59094/1/9781928424697.pdf#page=194.

- Maclennan, S. (2018). Campaign cries foul over name change. Online. https://grocotts.ru.ac.za/2018/06/29/campaign-cries-foul-over-name-change/

- Manca, A. R. (2014). Social cohesion. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 6026–6028). Springer.

- Mbenzi, P. A. (2019). Renaming of places in Namibia in the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial era: Colonising and decolonising place names. Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 25, 71–99. https://doi.org/10.59670/jns.v25i.177

- McKercher, B., Wang, D., & Park, E. (2015). Social impacts as a function of place change. Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.11.002

- Mkhize, T., & Naidoo, Y. (2023). Gender and race representation in street renaming in Pretoria/Tshwane. Map of the Month. Gauteng City-Region Observatory. https://doi.org/10.36634/YNCH9140

- Mudau, N. S. (2009). A critical analysis of the name change of Louis Trichardt to makhado with special reference to principles and procedures [ Unpublished MA-thesis]. African Languages, University of Limpopo.

- Musitha, M. (2016). The challenges of name change in South Africa: The case of Makhado Town. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2016.42010

- Ndletyana, M. (2012). Changing place names in post-apartheid South Africa: Accounting for the unevenness. Social Dynamics, 38(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2012.698949

- Njomane, A. (2009). A sociological study of public involvement in decision making, with special reference to the re-naming of the city of Pretoria. Mini-dissertation, master of arts in social impact assessment. Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg.

- Peng, J., Strijker, D., & Wu, Q. (2020). Place identity: How far have we come in exploring its meanings? Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00294

- Phalane, I. (2007). Renaming places. Place Branding, 2(1), 18–31. https://bowmanslaw.com/insights/dispute-resolution/renaming-of-places/

- Pretty, G., Chipuer, H. M., & Bramston, P. (2003). Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00079-8

- Proshansky, H. M. (1978). The city and self-identity. Environment and Behavior, 10(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916578102002

- Radding, L., & Western, J. (2010). What’s in a name? Linguistics, geography, and toponyms. Geographical Review, 100(3), 394–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2010.00043.x

- Rammile, S., & Matamanda, A. (2022, October 3–6). A place called home: Understanding toponyms. Unpublished paper, 58th ISOCARP world planning congress, Brussels, Belgium. https://isocarp.org/app/uploads/2022/11/ISOCARP_2022_Rammile_ISO397-1.pdf

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. Pion.

- Rose-Redwood, R., Alderman, D. H., & Azaryahu, M. (2010). Geographies of toponymic inscription: New directions in critical place-name studies. Progress in Human Geography, 34(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132509351042

- Sancho Reinoso, A. (2022). From place attachment to toponymic attachment: Can geographical names foster social cohesion and regional development? The case of South Carinthia (Austria). In O. R. Ilovan & I. Markuszewska (Eds.), Preserving and constructing place attachment in Europe (Vol. 131, pp. 239–254). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09775-1_14

- Savage, V. R. (2020). Place names. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International encyclopedia of human geography (2nd ed., pp. 129–138). Elsevier.

- Sepota, M. M., & Madadzhe, R. N. (2007). Renaming geographical entities and its effects: A case of Limpopo. South African Journal of African Languages, 27(4), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.2007.10587293

- Shamai, S., & Ilatov, Z. (2005). Measuring sense of place: Methodological aspects. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 96(5), 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00479.x

- Shields, R. (2023). ‘Rename the streets’: The challenges of decolonizing toponymy in Toronto Canada. Ukrainian Historical Review, II(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.47632/2786-717X-2023-2-139-153

- South African Geographical Names Council (SAGNC). (2002). Handbook on geographical names. Department of Sport, Arts, Culture.

- Spocter, M. (2018). A toponymic investigation of South African gated communities. South African Geographical Journal, 100(3), 326–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2018.1498382

- Steenkamp, J.-M. (2015). A toponymical study of place name heritage in Mossel Bay (Western Cape). MA (Linguistics) thesis, Department of Linguistics and Language Practice in the Faculty of the Humanities at The University of the Free State.

- Swanepoel, N. (2009). Capital letters: Material dissent and place name change in the ‘new’ South Africa, 2005–2006. Anthropology Southern Africa, 32(3–4), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2009.11499984

- Swanepoel, N. J. (2012). At the crossroads of history: Street names as monuments in the South African cityscape. Image & Text, 12(19), 80–91.

- Swart, M. (2008). Name changes as symbolic reparation after transition: The examples of Germany and South Africa. German Law Journal, 9(2), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2071832200006337

- Thornton, T. F. (1997). Anthropological studies of Native American place naming. American Indian Quarterly, 21(2), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.2307/1185645

- Webb, D. (2018). Change the names to rid SA of its colonial, apartheid past. Retrieved January 21, 2024, from https://mg.co.za/article/2018-09-21-00-change-the-names-to-rid-sa-of-its-colonial-apartheid-past/

- Williamson, B. (2023). Historical geographies of place naming: Colonial practices and beyond. Geography Compass, 17(5), e12687. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12687