Abstract

This article considers what would happen if unemployed people in South Africa had a right to a minimum level of regular work on decent terms. It looks at the example of India, where a law was passed in 2005 guaranteeing rural households up to 100 days of work a year at minimum wage rates. More than 55 million households now participate in this programme – a rare example of a policy innovation bringing about significant change in a society. India's employment guarantee has important implications for social and economic policy and gives new meaning to the concept of ‘a right to work’. The article explores how structural inequality limits South Africa's development options, and considers early lessons from South Africa's Community Work Programme to make the case for an employment guarantee in South Africa.

1. Introduction: The unemployment crisis

Footnote1 South Africa has one of the highest unemployment rates in the world, with formal unemployment at 25.7% in the second quarter of 2011 and a rate of 37% when discouraged work seekers are included (Stats SA, Citation2011). But bad as these unemployment statistics are, worse is that national averages conceal the spatially uneven distribution of unemployment, with levels being far higher in many former Bantustans and informal settlements; for example, 67% in Sakhisizwe Municipality in the Eastern Cape, 58% in Umzumbe Municipality in Kwazulu-Natal, and 57% in Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga (Stats SA, Citation2007). The extra burden of unemployment in poor areas is evidence of the extent of structural inequality in South Africa.

1.1 Structural inequality makes employment creation difficult

South Africa's structural inequality makes it unusually hard to create employment in marginalised areas of the country; rather, the effect is to perpetuate economic marginalisation (Philip, Citation2010a).

Analysis of these issues informed the outcomes of a process initiated by the Presidency during 2007–2009, and managed by TIPS (Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies), to develop strategies for the ‘second economy’.Footnote2 The conclusion was that, while the concept of the second economy was intended to focus policy attention on the wide disparities in South Africa, the concept itself was potentially misleading. South Africa has one economy, characterised by high levels of structural inequality; the challenge is to understand how this translates into poverty and economic marginalisation – and what to do about it (TIPS, Citation2009).

Structural inequality in South Africa is, to a large extent, a consequence of three main legacies of apartheid: the structure of the economy, spatial inequality and unequal access to human development. Philip Citation(2010a) explores the way the structure of the economy affects opportunities in the most marginal economic contexts and examines how this interacts with issues of spatial inequality. The starting point for the discussion is a South African conundrum: the question of why South Africa's informal and micro-enterprise sector is so small, despite the high levels of open unemployment.

While this is usually blamed on lack of entrepreneurship, lack of skills, and lack of access to credit (Herrington et al., Citation2008), these explanations overlook the way that the structure of the economy makes market access difficult. Most manufactured or processed goods bought by poor people are mass-produced in South Africa's core economy and are easily accessible in even the most remote spaza shops. This limits the opportunities for small-scale manufacturing of products that target poor consumers, which is the market environment that new entrepreneurs understand best. For this reason, local economic development strategies in other countries often focus on promoting an approach described by Philip as ‘local production for local consumption’ (2010a:7). In South Africa, however, a lack of viable opportunities for small-scale manufacturing of consumption goods aimed at poor consumers contributes to the bias in favour of retail activity in South Africa's informal sector, including street trading, spaza shops and shebeens.

Spatial inequality compounds the way the structure of the economy limits economic opportunities on the margins. A significant effect of the 1913 Land Act and later apartheid policy was to limit black people's access to land and force them into the labour market (Wolpe, Citation1972). For a while, land-based livelihoods supplemented the low wages of migrant workers. But mounting pressures on land led to rising dependence of the rural economy on remittances from migrant labour, coupled with a process of deagrarianisation in former Bantustan areas. As evidence, an average of less than 50% of rural households say they participate in agriculture; by March 2004, only 1.1% of those participating in agriculture earned their main income from it, and only 2.8% earned any additional income from agriculture (Aliber, Citation2005). While many other developing countries rely on the rural sector to act as an economic sponge, providing a level of subsistence or economic opportunity for large numbers of people who are not able to find other employment, rural areas in South Africa are unable to play this role to any great extent.

Small-scale manufacturing and small-scale agriculture are two of the most important avenues through which poor people typically enter into market activity. In South Africa, both are severely constrained. In addition, returns from economic effort in both these sectors are also often too low to lift people out of poverty (Du Toit, Citation2009; Neves, Citation2011). The combined effect of the constraints on these sectors is to make poor people in South Africa unusually dependent on wage remittances or social grants, and limits the scope for local economic development from below in the poorest areas. This dependence is deeply structural; it is not a state of mind or a consequence of a lack of skills or entrepreneurship. It could in fact be argued that the day-to-day reality of structural dependence is responsible to a large extent for the lack of economic dynamism and the levels of economic desperation that characterise many of South Africa's poorest areas. Structural solutions will therefore be required to resolve the problem; it is not one that markets – left to their own devices – can resolve. In the absence of broader processes of structural change, strategies that rely on creating employment by promoting self-employment, expecting poor people to navigate their way into markets from below, are destined to have a high failure rate – as they already do.

1.2 The costs of unemployment are unfairly distributed

Structural inequality makes employment creation difficult – and unemployment worsens inequality. John Maynard Keynes argued that unemployment is a function of economic cycles and is not the fault of the individuals directly affected; as a result, the costs of unemployment need to be treated as social costs, with the burden shared by society as a whole (Keynes, Citation1936). Ways of doing so have been central to the levels of equity achieved in much of Western Europe.

In South Africa there is no instrument in place to socialise the costs of unemployment; instead, the full brunt of these costs is borne by the individuals directly affected, and by their households. Important as South Africa's system of cash transfers has been in combating poverty, it mainly targets people whom society does not expect to work: children, pensioners and those with disabilities. For most unemployed people there is a significant social protection gap, with only about 3% of the unemployed receiving unemployment support at any one point in time (Klasen & Woolard, Citation2008). As a result, large numbers of unemployed people are economically dependent on goodwill transfers from family members who receive some form of social grant, on the diversion (and hence dilution) of the child support grant to support adults as well, or on wage remittances from friends or relatives who are employed. This ‘private safety net’ exists unevenly, creating high levels of vulnerability and placing the unemployed in a dependent relationship both socially and economically. Those who provide this safety net also have to shoulder a considerable burden, with unemployed household members dragging households deeper into poverty, and most of the unemployed living in households in the lowest two income quintiles (Klasen & Woolard, Citation2008).

This situation reinforces inequality and the insider-outsider dynamic. Those who manage to get a job can get ahead, with all the inter-generational advantages to them and their households. Those who cannot are not only economic outsiders – most are also outside the ambit of social protection, locked into dependent social and economic relationships and caught in a downward spiral of inter-generational disadvantage for them and the households on whom they rely.

1.3 Poverty is not only financial

A new form of cash transfer for unemployed people could help. But the crisis of unemployment in South Africa is about more than the money. Nearly 60% of the unemployed have never worked, and 59% of those who have worked have been unemployed for a year or more. The youth are worst affected (Banerjee et al., Citation2006).

It is well established that those who lose employment start to lose the skills, habits and disciplines of work (Irvine, Citation1984), while those who have never been employed never learn them, which also limits their chances of success in self-employment. Those who have never worked are less likely to obtain employment (Banerjee et al., Citation2006), and statistics show that those who have never been employed are the least likely to succeed in self-employment. As a result, large numbers of South Africans have only a tenuous relationship with the world of work. For many, the link between work and remuneration is simply absent from their experience: their access to income is through secondary sources, and via dependent relationships.

The over-riding priority in South Africa is to break this cycle: to provide work for those who need it, to instil the practices and disciplines of work, to institutionalise and embed the causal link between work and remuneration, to unlock the economic contribution of those excluded, and to give people access to the dignity of being productive rather than dependent (Philip, Citation2010b).

1.4 An employment safety net is needed while structural solutions take effect

A headline in a local newspaper quotes Cosatu General Secretary Zwelinzima Vavi as warning that the problem of jobless youth is a ‘ticking time bomb’ for South Africa (Business Day, Citation2011). Continued failure to create employment at the scale required is likely to heighten social tension, and this in turn is likely to limit the scope for economic growth and sustainable employment outcomes. The need to break this cycle is the core rationale for a form of employment safety net in South Africa. The aim would be to provide scope for economic participation even where markets do not do so – a minimum level of work for those who need it, not as an alternative to the other economic policies that are required but as a necessary condition for a longer-term process of economic change.

The argument that the state should act as employer of last resort where markets fail has a history in economic thought but only limited precedents in practice (Wray, Citation2007). India's introduction of an Act that guarantees rural households a minimum of 100 days of work a year changes that, creating a level of entitlement to work underwritten by the state. This model, described in Section 2 below, is of obvious interest for South Africa.

2. The policy context in South Africa

South Africa already has a policy commitment to public employment, through the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP), but achieving the scale required relative to the scale of the crisis remains a challenge. In Phase 1, from 2004/05 to 2008/09, the EPWP exceeded its target of achieving one million work opportunities (DPW, Citation2009). Important though this was, the target was cumulative over five years, and low relative to the number of unemployed people. In Phase Two, the targets have been significantly increased, to 4.5 million work opportunities, averaging 100 days per work opportunity, over five years to 2013/14. These figures are, however, still cumulative. An intergovernmental incentive to encourage additional employment creation has also been introduced.

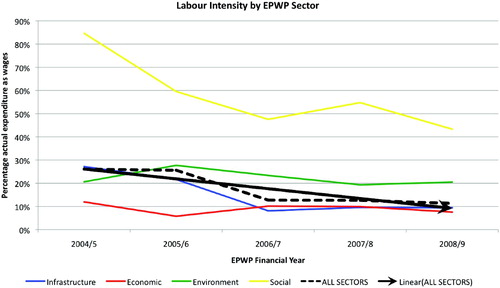

Certain features of the EPWP model mean it is not easy to scale it up significantly or to convert it into an employment guarantee. This is particularly so for infrastructure, where the EPWP was designed to increase the labour intensity of existing government investments. This is good spending policy, and increasing the labour intensity of existing expenditure is important for employment creation. However, with the exception of the social sector, most of the employment creation effects achieved by the EPWP are tied to outputs that are not intrinsically labour intensive, as shows. If the purpose is to take public employment to greater scale, it does not make sense to try to do so through the expanded delivery of programmes in which the labour content is low – unless such expansion is justified for other developmental reasons.

Figure 1: Labour intensity in the Expanded Public Works Programme FootnoteNotes.

Finally, because the core activities of the EPWP are tied to wider processes of delivery, it is often hard to target the poorest areas, where unemployment is highest. These are the areas where government delivery is typically weakest, and where the capacity to apply labour-based methods is often the most constrained. To go to scale and target the areas of greatest need, a complementary model for the delivery of public employment is required. We need to ask what such an approach might look like, and how the concept of an employment guarantee might be adapted to meet South Africa's particular set of needs – and constraints.

It was to find answers to these questions that the Community Work Programme (CWP) was initiated in 2007 by the Second Economy Strategy Project, in TIPS. The design phase of the CWP was run outside of government, with donor funding and strategic oversight from a steering committee comprising representatives of the Presidency and the Department for Social Development, and later also from National Treasury, the Department of Cooperative Governance and the Department of Public Works (TIPS, Citation2010).

In the June 2009 State of the Nation address, President Jacob Zuma committed government to ‘fast-tracking’ the implementation of the CWP. It was recognised as a new component of the EPWP, and was transferred into the Department of Cooperative Governance from April 2010.

The CWP is not, in its current form, an employment guarantee, because there is no legal entitlement to work on the scheme, and the number of people able to participate is limited by the budget available at each site. It is, however, a new modality for the delivery of public employment, designed with the explicit intention of developing and testing an approach that could be used to implement an employment guarantee in South Africa.

While still only an ant compared to India's elephant, the CWP's growth in two years, from 1500 participants in April 2009 to 99 179 participants in April 2011, demonstrates its potential to go to significant scale (DCoG, Citation2011). With a labour intensity of 65% at site level, it is highly cost effective not only compared with the EPWP but also by international standards (the Indian programme MGNREGA, described in the next section, has a labour intensity of 60%).

The CWP's current target is to establish a presence for the CWP in every municipality by 2014. If this is achieved, the institutional architecture required to roll out an employment guarantee will be in place. The steps required to make such a transition would not be huge but the development implications could be. The decision by the South African Cabinet in July 2011 to support the CWP to scale up to a million participants by 2013/14 improves the likelihood of achieving that goal (GCIS, Citation2011).

3. Innovation in India: The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) was promulgated in India in 2005 and renamed the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in 2009. Implementation began in February 2006. Through the Act, the state guarantees a minimum of 100 days of wage employment to every rural household with unemployed adult members willing to do unskilled work. By mid 2010, more than 55 million households were participating in the scheme – or approximately 4.5% of India's population. The equivalent participation rate in South Africa would be 2.2 million people.

MGNREGA aims to provide a strong social safety net for vulnerable groups by providing a fall-back employment source when other employment alternatives are scarce or inadequate. It aims to act as a growth engine for sustainable development in the agricultural economy, strengthen the natural resource base for rural livelihoods, create durable assets in rural areas, and empower the rural poor through the processes of a rights-based law, providing a model of governance reform ‘anchored on the principles of transparency and grass root democracy’ (Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, Citation2008).

Households apply to the local Gram Panchayat (village-level council) for a job card. Once this has been issued, they may submit a written application for employment, stating the time and duration for which work is sought. The Gram Panchayat must issue a dated receipt for the application, and make work available within 15 days of the application. This makes MGNREGA a system of work on demand, posing a significant planning challenge at the local level (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al., Citation2010). MGNREGA specifies that ‘if an applicant under this Act is not provided such employment within 15 days of his application seeking employment, s/he shall be entitled to a daily unemployment allowance which will be paid by the state government’ (Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, Citation2005).

Work is identified and planned by the local state, and must have a 60 : 40 wage : material ratio. Contractors are prohibited, and work should be provided within five kilometres of the village or else extra wages of 10% are payable (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al., Citation2010). The kind of work performed is specified at national level, and has focused on water conservation, drought proofing, constructing irrigation canals and other works to do with land, rural infrastructure and environmental services.

According to Amita Sharma, Joint Secretary of the Ministry of Rural Development, responsible for MGNREGA, ‘The most significant features of the NREGA are that it creates a rights-based framework and that it is a law’ (Sharma, Citation2010). This in turn creates an implementation paradox: work is an entitlement, but accessing that entitlement requires a certain level of information and organisation of rights-holders. As she explains:

Exercising rights, making choices, wresting entitlements from entrenched systems requires capabilities and most wage seekers lack these. How can they avail of the rights invested in them by the Act? There are no simple solutions. (Sharma, Citation2010)

MNREGA is implemented within a context of high public scrutiny and ongoing public debate. The Act was passed at the same time as India's Right to Information Act, which was promulgated as a consequence of a mass campaign against corruption, focused in part on public works programmes. In the state of Rajasthan, a grassroots organisation discovered large-scale fraud in the local public works programme and demanded information from local authorities. The situation is well described by Burra:

Soon villagers realised they had been defrauded and millions of rupees worth of work shown as having been completed was, in fact, never even taken up in the first place. Old public works were passed off as new. Local contractors and elites had received payments for nonexistent structures. Wages were supposed to have been paid to people who did not exist in the village. (Burra, Citation2008)

This level of electronic transparency is complemented by social processes. The Act requires that social audits be undertaken bi-annually at each site, with a community assembly held to verify the reported information. This has introduced unprecedented levels of local accountability – but the social audits pose their own challenges. In some cases, they have been criticised as merely a rubber stamp because villagers lack the capacity to hold officials to account. In yet other cases, public accusations of corruption leave little scope for due process for those accused – and no village is without its own particular history of scores to be settled. In addition, where the social audit becomes adversarial, the scope to use it to reflect on real constraints and challenges is easily lost, and even honest officials can find the process daunting. The crucial issue is the way space has been opened to strengthen local processes of holding public officials accountable – and the institutional practices emerging to address the risks described (see Philip, Citation2010b).

However, despite the ongoing contestation over the impacts of the programme, some important outcomes can be seen that illustrate its potential to transform rural India in profound ways. MGNREGA is setting the floor for labour market standards. In India, despite minimum wages in the agriculture sector, workers have had little alternative but to work for wages below this minimum. By paying a set minimum wage, MGNREGA provides an alternative – albeit limited to 100 days a year. Despite an outcry from landowners and the construction sector, complaining that MGNREGA has created labour shortages, and despite uneven impacts across states, the employment guarantee offers a powerful new instrument for setting minimum standards in contexts where they are unacceptably low. Linked to this has been the impact of equal pay for women and men – largely unprecedented in rural India. The provision of childcare facilities at increasing numbers of sites has enabled the economic participation of women – who make up over 50% of the participants.

MGNREGA is credited with reducing distress migration, and although the programme focuses on unskilled work, it has also created new skilled jobs in rural areas. Wages are paid through bank accounts, and this has stimulated financial inclusion. The sheer scale of MGNREGA has enabled wider ATM rollout in rural areas, and innovations such as using hand-held devices to capture bio-metric information, such as thumbprints, to confirm attendance at work sites (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al., Citation2010).

While all of these outcomes may still be ‘processes set in motion’, and their impacts and possibilities still in flux and often contested, MGNREGA has given the impetus to new development trajectories in rural India, and created a statutory right to work that is taking rights-based approaches into important new territory.

4. The Community Work Programme

4.1 Important design features of the CWP

The CWP is not an employment guarantee, but it was inspired by India's example, and was initiated to test ways in which such an approach could be adapted in South Africa. It provides participants with regular part-time work, typically two days a week or the monthly equivalent – adding up to 100 days a year, as in MGNREGA. The base wage rate in 2011 was R60 a day, aligned with the Ministerial Determination on minimum wage levels for workers in the EPWP. The CWP is an area-based programme, targeting poor communities in rural and urban areas. It was designed as ‘an employment safety net' providing a minimum level of regular and predictable work while wider policy processes to create decent work take effect (TIPS, Citation2010:5).

The CWP was also designed to demonstrate ways of taking development delivery to significant scale, where economic programmes targeting poor people in South Africa have tended not to do so. It has a target minimum of 1000 people per site. The sites vary in geographical size, currently covering an average of five wards. However, because the CWP is not a guarantee, work still has to be ‘rationed’ at sites, with participation rates defined not by the scale of demand but by the budgets that have been allocated. It is designed to be an ongoing programme, and while it may help participants access other opportunities, there is no forced exit back into poverty where such opportunities do not exist (TIPS, Citation2010). Where such work is rationed, however, issues of equity arise in terms of access to these work opportunities, with pressure to share the opportunities among those who need them – potentially diluting the poverty impacts of participation.

The work performed must be ‘useful work’ – work that contributes to the public good or to the quality of life in communities. It is identified and prioritised through participatory processes at community level. In a report to the CWP, the Implementing Agent, Seriti Institute, describes the role of these processes:

Part of the reason for the easy uptake of the CWP is that the consultation and community mapping exercises in each place have brought commitment to the process from a wide range of local actors. In each site there is an active Reference Group for the CWP, which draws in councillors, officials from the local municipality and relevant government departments, ward committee representatives and other community leadership. The existence of active reference groups has ensured that the CWP aligns with and contributes to the Integrated Development Plan in each locality and benefits from the insights and expertise of reference group members. (Andersson & Mkhize, Citation2009:4)

In the design phase, the concept was operationalised by two Implementing Agents, Seriti Institute and Teba Development. The CWP model initially required high levels of institutional innovation – and learning through trial and error. Funding flows were highly erratic. This negatively affected continuity and certainty at site level: not ideal for a programme testing the impacts of ‘regular and predictable’ work. However, uneven as these processes were, the lessons learnt informed the norms and standards of the programme.

CWP Implementing Agents devolve key functions to local level over time, but provide the capacity for work to start. Innovative methods of community consultation and skills transfer have been encouraged. For example, a methodology called the Organisation Workshop, first developed by Clodomir Santos de Morais in Brazil and adapted by Seriti Institute, is a three to four week action-learning process that can involve large numbers of people at community level. It teaches collective organisation, work organisation and task management skills – all crucial to the effective running of the CWP (Langa, Citation2011).

4.2 The rationale for a focus on regular and predictable work

The focus on regular access to part-time work is a response to the structural nature of unemployment in South Africa, which means that short-term, project-based work opportunities do not necessarily act as a stepping stone into formal labour markets and decent work. Where the market is not creating employment at the scale required, the CWP's priority is to provide participants with a predictable and ongoing earnings floor. Based on the typical patterns of expenditure observed in the context of social grants, the assumption is that a sustained increase in income is more likely to contribute to a sustainable improvement in nutrition, health and school attendance than a short-term spike in income from project-based work (Neves et al., Citation2009).

It is also recognised that unemployment leads to a lack of structure in people's lives, to isolation, and loss of self-esteem. The social consequences can include alcoholism, aggression, domestic violence, depression, anti-social behaviour and gangsterism (Irvine, Citation1984). The focus on regular work is intended to counter this by providing a level of predictability, structure and social inclusion. People who are unemployed are, however, rarely idle; they rely on a mix of casual work, income-generating activity and other livelihood strategies that nevertheless leave them underemployed. While these activities may not be lifting them out of poverty, it nevertheless makes economic sense to supplement rather than displace them. Part-time work enables this. Finally, a regular increase in income means a regular increase in consumption spending. In marginal rural economies and informal settlements, a boost of about R480 000 in local monthly spending creates new opportunities for small traders and local service providers.

4.3 The transformative potential of useful work

Demand for work exceeds the targets, with waiting lists at most CWP sites – and there is no shortage of useful work at the local level. Community mapping exercises and consultation have been used to inform the work agenda, with a common set of themes emerging across most sites.

Food security is a strong focus; by March 2011, the CWP had developed more than 27 000 food gardens (TIPS, Citation2011), with a direct link to care work:

Food gardens have been created in almost all communities, in the grounds of schools and clinics, on wasteland and in the backyards of vulnerable households… Schools receiving the food report that it can make an immediate and dramatic difference to learners' ability to participate in class, and improve their general performance. In many HIV/AIDS affected households, there is a decline in the availability of labour both from the person who is ill and from caregivers in the family. This contributes to a downward poverty spiral. By providing labour to food gardens for such households, this cycle can be averted or reversed. In some cases access to food has allowed patients being treated with antiretrovirals to regularise their treatment. (TIPS, Citation2010:6)

As these examples show, not all CWP work is unskilled, and not all CWP participants are unskilled either – among them are unemployed matriculants and university graduates. Institutional support is also being provided at schools. In Bushbuckridge, in partnership with local school governing bodies, the Bohlabela CWP has placed 550 education assistants in local schools, all of whom are unemployed matriculants or graduates from the area. Their tasks include helping teachers in classrooms with as many as 80 pupils, helping with homework classes and sports activities, and assisting in libraries where these exist and with administrative tasks (Cochrane, Citation2011; DCoG, Citation2011). In Gauteng, the CWP has partnered with the Natural Resource Management programme of the Department of Environmental Affairs to clean rivers in the Hartebeespoort Catchment area – many of which pass through human settlements, such as Bez Valley, Alexandra, Diepsloot and Mogale City. Community safety is also a recurrent theme. In Pfefferville in the Eastern Cape, dense bush alongside the Buffalo River was cleared to destroy criminals' hiding places: ‘Where before there was a dreaded forest there is now community parkland and vegetable gardens along the banks of the river’ (Andersson & Mkhize, 2009:10).

5. Social, economic and institutional impacts

We used to go bed with empty stomachs but now we are swiping cards like educated people. (Translated from a Zulu song of CWP participants in Nongoma, KwaZulu-Natal, in reaction to being paid into their own bank accounts by the CWP)

The outcomes of the CWP are still uncertain. Processes are in motion, nascent and in flux; some outcomes were intended, many have been unanticipated, and many challenges remain. As Oupa Ramachela (Chief Director, Special Projects Unit, Department of Social Development and CWP Steering Committee) explained:

The process of creating the CWP was not straightforward, it was not simple, it did not happen without tensions, contradictions and setbacks – and these are inevitably still part of the process. This is to be expected. (Comment made at the conference on ‘Overcoming Structural Poverty and Inequality in South Africa’, Boksburg, September 2010)

Some of the social impacts have been unanticipated. Malose Langa and Karl Von Holdt identify the combination of the Organisation Workshop and the CWP in Bokfontein, near Hartebeespoort, as critical factors giving a community wracked with conflict the tools to prevent an outbreak of xenophobic violence (Langa, Citation2011).

Regular access to the labour power of 1000 people is a valuable resource at local level, and one whose transformative capacity is only starting to be seen and understood in social and economic terms and in the lives of participants. Some early indications of impacts are the following:

| • | The transformative benefits of participation in work on the lives of participants, rekindling their sense of dignity, self-esteem and social and economic agency. | ||||

| • | The social and economic effect of the incomes earned on poverty indicators and the benefits for the local economy. | ||||

| • | The effect of the work on public goods and services delivered, with benefits for the community, local economy and local market development processes. | ||||

| • | The institutional benefits, including stronger participation in local development planning, growth in local capacity to identify, organise and manage work, strengthened forms of local accountability, and the deepening of democracy that this entails. | ||||

6. Conclusion: Building a society that works

This paper argues that an employment guarantee in South Africa is needed because of the deeply structural nature of inequality, the uneven distribution of unemployment, the spatially specific constitution of economic disadvantage, and the limits of market-driven approaches to employment creation in marginal areas. To solve these problems requires structural change, but such change will take time, and its benefits will reach the most marginalised last. The social implications and impacts of unemployment mean that urgent solutions are required in a country where there is no meaningful social protection targeted at unemployed people, and where the burden of unemployment is borne disproportionately by poor communities, with further disequalising and impoverishing effects on those who are already poor and disadvantaged.

This is the rationale for introducing a form of employment guarantee – to create access to employment where markets are failing to do so, to provide not only income but also the dignity of being productive rather than dependent, and to unlock their contribution to the economy.

An employment guarantee can take many forms. It differs from other forms of public employment, however, in being a rights-based approach to employment, obliging society to provide a minimum level of access to employment. As Sharma argues:

The creation of an Act that gives citizens a right to work does not have to be so daunting for government. What the Act simply does is to give citizens the leverage to hold government accountable for delivery, so that access to public employment is responsive to citizen need and so ensures a more efficient use of resources. Building the accountability of government in this way deepens and strengthens democracy, and it builds an active citizenry. (Interview, Amita Sharma, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Rural Development, Turin, 26 May 2010)

The paper also argues that, while the emphasis of arguments for the CWP and for an employment guarantee have been on the need for an employment safety net while wider processes of economic change deliver sustainable employment, it is possible that, taken to scale, an employment guarantee could also be an instrument for the structural change needed in marginal areas. Not the only one, certainly, but nevertheless a new policy instrument in which it is employment that drives public investment at the local level – in a way that addresses many of the necessary conditions for such structural change.

A sustained rise in local incomes is a necessary condition for wider local economic development, yet no such rise has yet been possible in South Africa. The incomes provided by an employment guarantee could break this cycle, making a direct investment in human development, community goods and services and natural capital and thus enhancing the potential for sustained social and economic development. The CWP model could achieve this in ways that also build local institutions, strengthen participatory development planning, deepen local democracy, and unlock the potential agency within communities. An employment guarantee need not be just a safety net where markets fail; it could also be an instrument of structural change in marginal areas, investing in people as well as in community assets and services, and in the process, creating new opportunities for sustainable economic development.

Notes

1This paper was first presented at the national conference on ‘Overcoming structural poverty and inequality in South Africa’, September 2010. It is available at www.tips.org.za (see Philip, Citation2010b).

2This strategy process was led by the author. The analysis in this article builds on the outcomes of that process.

Source: McCutcheon & Taylor Parkins Citation(2010).

References

- Aliber, M , 2005. "Synthesis and conclusions". In: Aliber, M , De Swardt, C , Du Toit, A , Mbhele, T , and Mthethwa, T , eds. Trends and Policy Challenges in the Rural Economy . Pretoria: HRSC (Human Sciences Research Council) Press; 2005. pp. 87–108.

- Andersson, G & Mkhize, S. 2009. Proposal to the Community Works Programme Steering Committee, October. Seriti Institute, Johannesburg..

- Banerjee, A, Galiani, S, Levinsohn, J & Woolard, I, 2006. Why has unemployment risen in the new South Africa? Working Paper No. 134, Centre for International Development (CID), Harvard University..

- Burra, N, 2008. Transparency and accountability in employment programmes: The case of NREGA in Andhra Pradesh. Occasional Paper, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, New York. www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/EFFE/Transparency_and_accountability_in_employment_programme_Final_version.pdf Accessed 29 October 2011..

- Business Day, 2011. Jobless youth a ‘ticking time bomb’ for SA, Vavi warns. 7 June, p. 1..

- Cochrane, M, 2011. Studying the impact of the community work programme on its participants. Unpublished paper, Teba Development, Johannesburg..

- DCoG (Department of Cooperative Governance), 2011. Communities at Work: Community Work Programme 2010/2011. TIPS (Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies), Pretoria..

- DPW (Department of Public Works), 2009. Expanded Public Works Programme five year report 2004/05–2008/09 – Reaching the one million target. www.epwp.gov.za/downloads/EPWP_Five_Year_Report.pdf Accessed 8 January 2011..

- Du Toit, A , 2009. Adverse incorporation and agrarian policy in South Africa or, how not to connect the rural poor to growth . Presented at In proceedings of the BASIS Conference on Escaping Poverty Traps. Washington, DC, 26–27, February, www.basis.wisc.edu/ept/dutoitpaper.pdf Accessed 28 July 2011.

- GCIS (Government Communications and Information System), 2011. Statement on the Cabinet Lekgotla of 26–28 July, Pretoria. www.info.gov.za/speech/DynamicAction?pageid=461&sid=20345&tid=38379 Accessed 2 November 2011..

- Herrington, M, Kew, J & Kew, P, 2008. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South African Report 2008, Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town. www.gsb.uct.ac.za Accessed 28 July 2011..

- Irvine, B , 1984. "The psychological effects of unemployment: An exploratory study". In: Carnegie Enquiry into Poverty and Development in Southern Africa (2nd), April . Cape Town. 1984.

- Keynes, J M , 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money . London: Palgrave Macmillan; 1936.

- Klasen, S , and Woolard, I , 2008. Surviving unemployment without state support: Unemployment and household formation in South Africa , Journal of African Economies 18 (1) (2008), pp. 1–51.

- Langa, M , 2011. "Bokfontein: The nations are amazed". In: Von Holdt, K , Langa, M , Molapo, S , Mogapi, N , Dlamini, J , and Kirsten, A , eds. The Smoke that Calls: Insurgent Citizenship, Collective Violence and the Struggle for a Place in the new South Africa . Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation; 2011.

- Lieuw-Kie-Song, M , Philip, K , Tsukamoto, M , and Van Imschoot, M , 2010. "Towards the right to work: Innovations in public employment programmes (IPEP)". In: Employment Intensive Investment Programme . Geneva: International Labour Office; 2010.

- McCutcheon, R , and Taylor Parkins, F , 2010. Rhetoric, reality and opportunities foregone during the expenditure of over R40 billion in the infrastructure sector, 2004 to 2009 . Presented at TIPS & DPRU (Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies & Development Policy Research Unit) Annual Forum 2010. Johannesburg, 27–29, September.

- Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, 2005. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). www.nrega.nic.in Accessed 28 July 2011..

- Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, 2008. The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) Operation Guidelines 2008, 3rd edn . New Delhi. 2008, http://nrega.nic.in/Nrega_guidelinesEng.pdf Accessed 18 November 2011.

- Neves, D , 2011. Money and Sociality in South Africa's Informal Economy. Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) . School of Government, University of the Western Cape; 2011.

- Neves, D , Samson, M , Van Niekerk, I , Hlatshwayo, S , and Du Toit, A , 2009. The Use and Effectiveness of Social Grants in South Africa . Johannesburg: Finmark Trust; 2009, www.finmarktrust.org.za Accessed 2 August 2011.

- Philip, K, 2010a. Inequality and economic marginalisation: How the structure of the economy impacts on opportunities on the margins. Law, Democracy and Development 14, 1–28. www.ldd.org.za/images/stories/Ready_for_publication/philip_doi.pdf Accessed 1 November 2011..

- Philip, K , 2010b. Towards a right to work: The rationale for an employment guarantee in South Africa . Presented at Paper presented at the national conference on ‘Overcoming Structural Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: Towards Inclusive Growth and Development’, co-hosted by SPII (Studies in Poverty and Inequality Institute), PLAAS (Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies), the Isandla Institute and the PSPPD (Programme to Support Pro-Poor Policy Development) unit within the Presidency. Boksburg, Johannesburg, 20–22, September, www.tips.org.za/files/philip_rationale_for_an_employment_guarantee_.pdf Accessed 15 November 2011.

- Sharma, A , 2010. "Rights-based Legal Guarantee as Development Policy: The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act". New Delhi, India: UNDP (United Nations Development Programme); 2010, www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/reports-documents/rights-based-legal-guarantee-development-policy-mahatma-gandhi-national-rural Accessed 18 November 2011.

- Stats SA (Statistics South Africa), 2007. Community Survey 2007 . Pretoria: Stats SA; 2007.

- Stats SA (Statistics South Africa), 2011. Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Second Quarter 2011 . Pretoria: Stats SA; 2011.

- TIPS (Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies), 2009. "Second Economy Strategy Project, 2009". In: Addressing Inequality and Economic Marginalisation: A Framework for Second Economy Strategy . Pretoria: TIPS; 2009, www.tips.org.za/programme/2nd-economy-strategy-project Accessed 1 November 2011.

- TIPS (Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies), 2010. Community Work Programme Annual Report 2009/10 . Pretoria: TIPS; 2010.

- TIPS (Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies), 2011. Community Work Programme: March 2011 Outputs Report . Pretoria: TIPS; 2011.

- Wolpe, H , 1972. Capitalism and cheap labour power in South Africa: From segregation to apartheid , Economy and Society 1 (4) (1972), pp. 425–56.

- Wray, L R , 2007. "The employer of last resort programme: Could it work for developing countries?". In: Economic and Labour Market Papers . Geneva: International Labour Office; 2007.