Abstract

The Green Fund is a national fund aimed at supporting South Africa's transition towards a green economy. The Fund, managed by the Development Bank of Southern Africa on behalf of the Department of Environmental Affairs, is a three-year programme promoting innovative and high-impact green interventions. The Green Fund is mandated to provide catalytic finance to project initiation and development; policy and research development; and capacity-building initiatives that have the potential to support South Africa's transition to a green economy. This paper provides insights into the establishment of the Green Fund and draws out lessons for the development and growth of environmental finance capabilities in southern Africa.

1. Introduction

The shift to a green economy is expressed as a ‘just transition to a resource-efficient, low carbon and pro-employment growth path’ in South Africa's National Strategy for Sustainable Development and Action Plan (DEA, Citation2011:7). Since the Green Economy Summit in 2010, a suite of supportive macro-economic policies, framework and strategy documents, and sector-specific policies now echo the South African government's commitment to this green transition. This policy framework set the stage for the introduction of the Green Fund in 2012 – a national environmental programme managed and implemented by the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) on behalf of the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA).

Targeted public finance is regarded as vital in catalysing the transition to a green economy by decreasing investment risk, creating a stimulus for green investments and leveraging private finance for green investments (UNEP, Citation2010; Venugopal & Srivastava, Citation2012). Like other environmental funds (EFs) in southern Africa, for instance the Environmental Investment Fund of Namibia and Maurice Ile Durable in Mauritius, the Green Fund was established with fiscal support. Among the key mandates of the Green Fund is to leverage and attract additional resources to support South Africa's transition to a green economy by using public finance as a stimulus for green investments (Green Fund, Citation2014).

This paper will explore the initiation of the Green Fund by outlining the origin and establishment of the Fund, evaluating its governance systems; and investigating the fund disbursement and delivery in its first two years of operation. It will extract key lessons from EFs and assess the Green Fund's initial performance against key criteria used to evaluate EFs. Central criteria for the successful establishment and operation of EFs have been discussed extensively in the literature, most notably by the Global Environmental Facility and the Interagency Planning Group on EFs. These studies, as well as other key insights from the EF literature, are discussed below.

2. Environmental funds: An overview

The past 20 years have seen the creation of a number of EFs, with the period 1994–1997 witnessing a doubling of national EFs (Bayon et al., Citation1999). This can be attributed to some extent to the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Rio Summit). In the years leading up to and immediately following the Rio Summit, EFs were seen as important financing mechanisms for the implementation of national environmental action plans and agendas (Bayon et al., Citation1999; GEF, Citation1999; Norris, Citation2000).

Interest around the establishment of EFs has grown and a number of studies providing an overview of the origin, governance structure, scope of activities, priorities, funding instruments and the limitations and successes of EFs now exist (GEF, Citation1999; Norris, Citation2000; Scholtens, Citation2011; Thualt et al., Citation2011; Roux, Citation2013). Moreover, the importance of climate finance in addressing both climate change and sustainable development objectives has also broadened the scope and mandate of EFs (Schalatek & Bird, Citation2012; Venugopal & Srivastava, Citation2012; Amin et al., Citation2013). This section draws on this literature to provide a backdrop for the lessons learnt in respect of the subject matter of this article; that is, the establishment and functioning of the Green Fund of South Africa since its creation in 2012.

2.1 Origins, governance and structure of environmental funds

As alluded to earlier, the Rio Summit was instrumental in the creation of a number of EFs and highlighted the potential of these funds as financing mechanisms for the implementation of national (and global) environmental agendas. There is great variety in the structure, governance, funding priorities and purposes of EFs (GEF, Citation1999; Norris, Citation2000; Oleas & Barragán, Citation2003), but among the key success factors of EFs, as outlined in a GEF evaluation of EFs, is strong government commitment. Although fund mobilisation, priorities and delivery mechanisms vary across countries and regions, they tend to exhibit common elements of integration into national environmental and development agendas. EFs are said to be institutions with multiple roles that vary in accordance with the purpose and national context (GEF, Citation1999). Their scope has included the development of national environmental and conservation strategies, providing funding and technical expertise, building capacity and, more recently, supporting the transition to low carbon development paths (Whande, Citation2011).

The governance structures of EFs will vary in relation to their origins; that is, from the public or private sphere. According to Oleas & Barragán (Citation2003), a key lesson emerging from Latin American and Caribbean EFs is that the most successful EFs are those that are created in the private domain and which involve both government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in a balanced relationship. Government entities are minority stakeholders, and the governing bodies of these EFs include representatives from both the public and non-governmental sectors. While it is becoming more common for government ministries to have oversight for EFs, as is the case of FONERWA (Rwanda) and the Green Fund, there are strong suggestions from the literature that transparent and accountable governance systems, which have representation of diverse stakeholders, are required to ‘guarantee greater transparency in management’ (Thualt et al., Citation2011:5; WIOMSA, Citationn.d.).

2.2 Financial structure and focus of environmental funds

Studies highlight that EFs are structured in three main ways: endowments (which invest their capital and only use income from those investments to finance activities), sinking funds (which are designed to disburse their entire principal and investment income over a fixed period of time) and revolving funds (which receive new resources on a regular basis) (Bayon et al., Citation1999; Norris, Citation2000). Transition economies, in Central and Eastern Europe, use public EFs to mitigate their pollution and related environmental challenges through public finance mechanisms. Funds are mobilised from government and quasi-governmental institutions that are capitalised through diverse revenue streams (Norris, Citation2000). This model, using public finance to act as a stimulus for private and donor investments, is being mooted in a number of publications dealing with financing of the green economy (UNEP, Citation2009; Venugopal & Srivastava, Citation2012).

Fund priorities and focus areas vary across countries and regions. One study on EFs in Latin America and the Caribbean highlights the main thematic areas of EFs as protected areas, environmental conservation and sustainable development (Oleas & Barragán, Citation2003). Other funds such as FONERWA (Rwanda) and Maurice Ile Durable (Mauritius) provide funding across a wide range of thematic financing windows and programmes such as conservation and sustainable natural resources management, green economy, technology transfer and implementation, environment and climate change mainstreaming, and energy (Mahomed, Citation2013; Roux, Citation2013).

Priority setting has been identified as a critical operational tool for EFs. It is noted that establishing clear priorities facilitates effective grant cycle management and that broad and ill-defined priorities can bring administrative difficulties (Oleas & Barragán, Citation2003). Funds that lack a focused strategy run the risk of spreading their resources too thinly, financing many discrete efforts but cumulatively failing to achieve any significant impact. Furthermore, experience has shown that several ‘grant funds’ were overwhelmed with project proposals during their first year or two and spent considerably more time and resources to respond to them than they had planned (Oleas & Barragán, Citation2003). Authors have taken the view that EFs should therefore invest in building the capacity of key stakeholders in the development of concept notes and project proposals targeting priority areas (Bayon et al., Citation1999; Roux, Citation2013).

While there are a number of EFs operating in South Africa, the Green Fund was established with the express purpose of supporting South Africa's transition to a green economy. The section below will outline the origins, structure and implementation of the Fund and draw out key lessons for environmental finance mechanisms. The discussion will be structured primarily around three critical areas – fund establishment and mobilisation, fund administration and governance, and fund disbursement and delivery.

3. The Green Fund: Transitioning South Africa to a green economy

Directives in support of South Africa's transition to a low carbon and greener economy are captured in a number of national macro-economic and sectoral policy documents (). This policy commitment, which can be traced back to the Green Economy Summit in 2010, led to coordinated efforts by the DEA, DBSA, Economic Development Department and Industrial Development Corporation to undertake an extensive process of research and consultation to identify green economy programmes, as well as the resource requirements for transitioning to a green economy (DBSA, Citation2011a; Naidoo, Citation2013). Upon the release of the DBSA (Citation2011a) report Programmes in Support of Transitioning South Africa to a Green Economy, the DEA and DBSA began to address the financing pathway to transition South Africa to a green economy – the Green Fund emerged from this process.

3.1 Origins and establishment of the Green Fund

The Green Fund has been structured to reflect national green economy policy priorities and the complex cross-linkages between macro-economic and sectoral policy focus areas. Unlike neighbouring Mozambique, South Africa has not yet adopted a national green economy strategy or roadmap, but uptake of the concept by government has been significant and several provinces have drafted green economy strategies (GCRO, Citation2011; LEDET, Citation2013; Western Cape Government, Citation2013). Sectoral strategies, such as an energy efficiency strategy, biofuels strategy and a roadmap for electrical vehicles, have also been developed at national level to explore the role of key sectors in the green economy transition. Policy support for the transition to a green economy in South Africa is notable in key macro-economic policies, as well as sectoral and cross-cutting policy documents such as the National Climate Change Response White Paper (DEA, Citation2010) and the Industrial Policy Action Plan 2 (dti, Citation2010) ().

Following the 2010 Green Economy Summit, a process to identify the scope, focus and financing of the green economy transition was initiated. This process involved a number of initiatives, which included a public call for expressions of interest for green projects managed by the DEA, a green economy programme identification process (DBSA, Citation2011a), and an investigation into the resource requirements to kick-start South Africa's green economy transition, conducted by the DBSA. The programme identification exercise, which included the responses to the expressions of interest, outlined key green economy focus areas that were aligned with government priorities (DBSA, Citation2011a). Thereafter, the DBSA undertook a market scan of available environmental finance mechanisms including fiscal, private and public funding sources (Naidoo, Citation2013). Engagement with key stakeholders confirmed the need to establish a public EF that could play a catalytic role in facilitating investment in green economy initiatives. The Green Fund was regarded as additional and complementary to existing fiscal allocations supporting South Africa's green transition.

In February 2012, the Minister of Finance pronounced an allocation of ZAR 800 million over three years to the DEA for the set-up and operationalisation of the Green Fund. DEA and the DBSA signed a Memorandum of Agreement, effective from 1 April 2012, whereby the DBSA was appointed as the implementing agent of the Fund.

The Green Fund was designed on the basis of transition fund principles, in as much as it would endeavour to finance ‘activities that enable systemic societal shifts towards the desired transition impact’ (DBSA, Citation2011b:6) – in this case a green economic path. Transition funds can be structured for a defined period of time to focus on targeted interventions, such as providing an evidence base for developing a new government policy or new sector. With this intent, the Fund had to identify and remove market barriers through policy feedback loops which would then assist government in structuring an enabling environment supportive of a green transition. Transition funds also have to allow for refinement based on the evidence base drawn from interventions financed. The operational parameters of the Green Fund, from the governance structures to focus areas and financial instruments, can thus be recalibrated based upon the lessons learnt.

The Green Fund aims to provide catalytic finance to facilitate investment in high-impact, innovative green initiatives that reinforce policy objectives. The Fund supports initiatives which are at various phases of the innovation value chain, but will, in time, shift its focus from the preparation of robust demonstration projects to the replication and scaling of projects that advance the green economy agenda. The Green Fund will respond to market barriers currently hampering South Africa's transition to a green economy by:

Promoting innovative and high-impact green programmes and projects;

Reinforcing sustainable development and climate policy objectives through green interventions;

Building an evidence base for the expansion of the green economy; and

Attracting additional resources to support South Africa's green economy development. (Green Fund, Citation2014)

While the Green Fund was conceptualised as a public EF and capitalised with an initial fiscal allocation over a three-year period, one of the strategic objectives of the Fund is to leverage additional financial resources. This is expressed in its investment philosophy (Green Fund, Citation2013a). While fiscal commitment has been extended to five years, the Fund has not yet leveraged the aggregated matching funds that demonstrate investor confidence in green economy initiatives. This has only been achieved at a project level where applicants have been required to provide a percentage of the full project cost as matching funds to illustrate commitment.

3.2 Governing the Green Fund

The operationalisation of the Green Fund required the establishment of an investment team, a dedicated secretariat for the administration and policy advisory services, and governance structures (Green Fund, Citation2014). These structures include a Management Committee (Mancom) and a Government Advisory Panel.

The Green Fund team, based at the DBSA, assumed duty between August 2012 and February 2013 and brought together a range of skill sets, including investment and portfolio analysis, project preparation and evaluation, environmental policy analysis and research, monitoring and evaluation, and environmental expertise. The team draws on DBSA systems and procedures where appropriate, for example project preparation, appraisal and contracting processes. While the DBSA-based team is responsible for project identification, assessment and evaluation, policy and advisory services and monitoring and evaluation, all funding approvals are made by the Green Fund Mancom.

The Mancom was established in April 2012 to provide strategic oversight for the implementation of the Fund in addition to approving funding of all project proposals. The committee meets at least quarterly and is chaired by the Director-General of DEA. Mancom members are made up of representatives from DEA, National Treasury and the DBSA. The committee is also responsible for approving all operational documents of the Fund, such as the monitoring and evaluation framework, investment strategy and intellectual property policy. A Government Advisory Panel, which met for the first time in July 2012, was also initiated to advise on the positioning of the Green Fund and to share information with relevant departments on public-sector environmental and green economy initiatives. This structure meets on a bi-annual basis and is attracting growing participation by key sector departments.

3.3 Fund disbursement and delivery

3.3.1 Focus areas and financial instruments of the Green Fund

The Green Fund has been set up around three functional areas: project development and/or investment in high-impact green projects and programmes; capacity-building in green initiatives; and research and development initiatives that feed into the green economy policy and regulatory environment. In the run-up to the establishment of the Fund, the DBSA commissioned a study on priorities and opportunities for the Green Fund (Green Fund, Citation2012a). This study, which included stakeholder consultation with public-sector, private-sector and community-sector organisations, was instrumental in delineating the focus areas, as well as the thematic windows of the Green Fund.

Based on extensive research and consultation, three thematic windows, which reflect policy priorities, were identified as the initial thematic windows of the Fund (Green Fund, Citation2012a). These also provide coherence to enable the Fund to focus on projects that have the highest impact and catalytic effect in a particular sector. The thematic windows were identified as Green Cities and Towns, Low Carbon Economy and Environmental and Natural Resource Management. The focus areas and eligibility criteria for each window is different and informed by key national policies. However, all applications to the Green Fund would be appraised in relation to four central principles: relevance, which requires demonstration of alignment to thematic funding windows; innovation, which requires that the initiative be new and unique in the green economy space (innovation can relate to any of the following aspects: technology, business model, institutional arrangements, or financing approach); additionality, by which financing complements available resources and does not substitute or crowd out private investment; and the ability to scale up and/or replicate, whereby the project has the potential to be rolled out to other sites and/or to be implemented on a large scale (Green Fund, Citation2014).

Financial support in all three focus areas of the Fund, project development, research and capacity-building, would be provided along these thematic areas. The Fund prioritises impact-focused green economy initiatives and has made available a suite of financial instruments, which are detailed in its Investment Strategy (Green Fund, Citation2013a). These instruments encourage risk sharing through co-investment, and seek multiple outcomes including a reasonable financial return. The instruments through which funding is provided include grants (recoverable and non-recoverable), loans (at concessional rates and terms), and equity. The rationale for the selection of these instruments is outlined in the Fund's Investment Strategy (Green Fund, Citation2013a).

The following section will outline the initiation of the Green Fund by considering the Fund's delivery mechanisms. It provides a snapshot of the emerging green economy market in South Africa, and outlines the key sectors, applicant types and financial modalities that emerged from the first two years of the Fund's operations.

3.3.2 Gearing up for the green economy in South Africa: Operationalising the Green Fund

The mandate of the Fund, to play a catalytic role in supporting South Africa's green economy transition, was put into motion through a public request for proposals (RFP). Thus far, this has been implemented in two of the three functional focus areas outlined earlier – project finance and research and policy development. Two public RFPs were initiated for the project development and research focus areas in 2012 and 2013 respectively, while the design and programming of the capacity-building funding facility of the Green Fund is still under consideration. The overwhelming response to these calls is indicative of the growing demand for environmental finance in South Africa. The process to solicit, screen, evaluate and fund green economy initiatives is discussed below.

3.3.2.1 The first request for proposals: Financing green economy projects

The first RFP, with a focus on project development across the three thematic windows, was initially allocated 75% of the Green Fund budget, as per the Memorandum of Agreement between the DBSA and DEA. The RFP was launched in September 2012 and closed a month later in October 2012. A total of 590 applications, valued at almost ZAR 10 billion, were successfully submitted. Projects were submitted by private, public and civil society organisations with an interest in developing and implementing green economy projects across the innovation value chain, from pilot and demonstration to implementation stage. The RFP application process was conducted on the basis of a set of prescribed application guidelines (Green Fund, Citation2012b), which communicated the eligibility criteria, the thematic windows, the available funding instruments and the instructions for completing the application process.

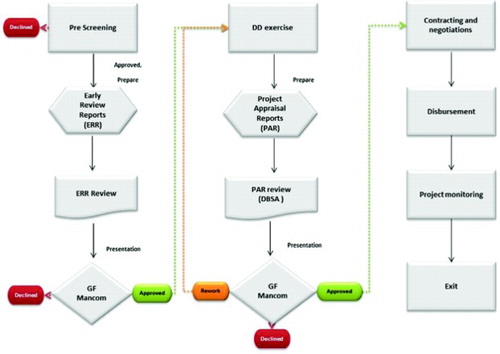

The initial project screening, which was conducted online based on the completeness of the submissions, retained 67% of the 882 registered applications. The 590 submitted projects were then reviewed and screened by a panel comprising sector specialists from the Green Fund and DBSA, in accordance with the eligibility criteria of the Fund. Of the three thematic windows, the Green Cities and Towns window (51%) dominated the applications, followed by the Environmental and Natural Resources Management (25%) and Low Carbon Economy windows (24%) (). Upon completion of the screening process, approximately 88 projects remained. These were then subjected to initial review by the Green Fund investment team who subsequently prepared Early Review Reports (ERRs) with decision recommendations to the Mancom.

ERRs summarise a project's key business concept and assesses each project's perceived contribution to the transition to a green economy and related developmental benefits. Early risk assessment and potential deal-breaking elements are also identified at this stage. Upon completion of the screening, evaluation and early review process, the Mancom recommended about 62% of the projects (50) for due diligence. The appraisal process is outlined in .

During the due diligence process, an assessment of the full business potential and risks as well as an investigation into the bankability, scalability, additionality, replicability and sustainability of the project is undertaken. This process also draws on sector specialists if required. A detailed project appraisal report is then put before the Mancom for a funding decision. To date, the Mancom has approved 22 project applications.

Of the 22 projects approved to date, 17 have advanced to the contracting and disbursement stage. The Green Cities and Towns window (60%) continues to dominate the portfolio while Environmental and Natural Resource Management and Low Carbon Economy share 22% and 15% of the funding (). This is aligned to the trends that emerged at the application stage.

The majority of the projects (89%) are grant-funded while the balance of 11% was availed through concessionary loans. The grants were further split into recoverable (40%) and non-recoverable grant (49%). This scenario was largely attributed to the fact that the majority of the projects were from the NGO, local and national government departments and needed de-risking before graduating to commercial funding options.

The underlying objective of the first RFP was to support projects that catalyse the transition to a green economy. The process was instrumental in identifying the key sectors driving the green economy transition in South Africa, as well as highlighting sectors that could require additional support. Notwithstanding the wealth of lessons emerging from this process, several challenges were experienced during the first call. The application process was onerous for some applicants who either deferred submission towards the close of the call or had poor Internet connectivity. The short application period of one month did not facilitate the application process either. Mixed feedback was received from applicants during the due diligence process regarding the online application process. While some viewed it as a transparent and efficient way of handling publicly-funded projects, others suggested that alternative application submission methods such as hard-copy or email applications be considered in future calls.

The screening and evaluation process of the applications was rigorous and was modelled on the project appraisal and evaluation processes of the DBSA. The Green Fund endeavoured to communicate funding decisions in a timely manner and established a grievance system by which applicants could interrogate the evaluation and decision-making processes. Lessons learnt from the first call were instrumental in shaping the design and implementation of the second public call.

3.3.2.2 The second request for proposals: Research and policy development to advance a green economy

The conceptualisation of South Africa's transition to a green economy, in theory and in practice, is still at the beginning stages. This second RFP, entitled ‘Research and Policy to Advance the Green Economy in South Africa’, sought to improve the quality and effectiveness of research on green economy policy, planning and implementation in South Africa. It was also set up in response to the Fund's mandate, which assigned 5% of the budget allocation to support research and development. Research and policy development grants would be awarded to successful applicants who submitted applied and/or policy research applications that advance the national green economy policy vision.

This RFP also supported the efforts of the DEA to strengthen the science–policy interface in the green economy sector, as set out in its Environment Sector Research, Development and Evidence Framework (DEA, Citation2012). The Green Fund was thus well positioned to assume the role of a knowledge-broker by ensuring that the transition to a green economy is driven by a robust, evidence-based policy-making process. The RFP required applicants to formulate research questions that addressed green economy policy objectives; articulated innovative and practical research solutions to policy implementation problems; and translated research findings into formats that are intelligible to a range of stakeholders (Green Fund, Citation2013b).

The RFP opened on the 1 February 2013 and closed on 28 March 2013. Applicants were invited to apply in the existing thematic windows of the Green Fund or to submit applications under a new thematic window – Innovation for the Green Economy, which examined innovative approaches (planning, technological, policy development) that advance green economy objectives. The rationale behind this window was to invite research applications that would provide innovative solutions – financial, institutional, planning and technological – to support South Africa's transition to a green economy.

The RFP incorporated the lessons learnt during the first RFP by extending the application period, improving access to technical support and communicating frequently with applicants. Despite efforts to streamline the application process, there were still a significant number of applicants who were not able to complete the application online. By the deadline, 317 applications were registered on the online application system. Of these, 155 applications, valued at ZAR 1.6 billion based on total funding requested, were finalised and submitted by the due date. The screening and evaluation process now had to identify the research applications that were aligned with the thematic windows; produced clear lessons to deepen understanding of green economy policy and practice in South Africa; and were innovative and contributed to policy or practical solutions to advance the green economy agenda.

The initial findings reveal that the thematic window Green Cities and Towns (35%) received the highest number of applications while the remaining categories were more evenly distributed: Low Carbon Economy (20%), Environmental and Natural Resource Management (24%) and Innovation for the Green Economy (21%) ().

The 155 submitted applications were subjected to the evaluation process outlined in . Both the application guidelines and review process of the public requests for proposals were made available online and were therefore accessible to applicants. A review team, consisting of environmental specialists from the Green Fund and DBSA and representatives from both the DEA and Department of Science and Technology, was constituted to screen and evaluate the research applications. A team approach was preferred to reduce subjectivity of the screening and review processes. After the review stage, 25 applications were short-listed for decision by the Mancom.

Steps 1 to 3 of the evaluation process were completed in three months; that is, by the end of June 2013. Delays were experienced in the allocation of funding, thus having an impact on the approval and contracting of the research grants. Sixteen of the 25 short-listed applications have since been approved, contracted and funded.

The research RFP was initiated to build a knowledge economy supportive of South Africa's green transition, and initiate an evidence-based green economy policy development process. Initial lessons that can be distilled from this RFP process relate to process as well as the substance of green economy research in South Africa. The online application process, which some applicants found fairly straightforward, posed a challenge to others. A similar recommendation to the first RFP was made whereby applicants requested to have an option to submit hard-copy submissions or to email applications.

The screening and evaluation process was designed to maximise opportunities for peer review, and individual reviewers could also draw on technical experts if required. In the future, research institutes could be drawn into the review team to enrich the evaluation system. While the Green Fund has communicated with applicants throughout the screening and evaluation process, the length of time that has elapsed since the closing date and the approval process has created a level of uncertainty and frustration amongst applicants. This has been largely due to an unexpected misalignment with funding allocations. One way to address this in future would be to publish the time-frame of the evaluation process at the application stage.

The overwhelming response to this RFP confirms that this knowledge sector should be prioritised within the research agenda of the country. National research bodies should provide more opportunities for the research community to interrogate South Africa's transition to a green economy. Moreover, this science–policy interface should be mediated by an independent process in which all knowledge sectors and actors can present their views on South Africa's green transition.

3.3.2.3 Building capacity to transition South Africa to a green economy

Funding capacity-building projects and programmes that support the transition to a green economy constitutes the third functional focus areas of the Green Fund. The Fund seeks to support innovative and strategic capacity-building initiatives that will strengthen capabilities (infrastructure, resources and products, skills) to pursue green economy policy development, planning and implementation. In contrast to the approach adopted in addressing the project and research support (i.e. by way of a public RFP), the approach to operationalising this focus area has been to understand the policy framework; undertake a stakeholder engagement process; and, based upon these, design the capacity-building support facility of the Fund.

A policy review of capacity-building was initially undertaken and this informed the multi-stakeholder (government, private and civil society) engagement process in the form of a roundtable discussion, Building Capacity for a Green Economy, convened in May 2013. The purpose of the roundtable was to identify priority capacity-building areas that require support, opportunities for partnerships, and insights on the formulation and design of the Green Fund's capacity-building support facility. Participants identified the need for strategic, targeted interventions that could begin to coordinate green economy initiatives, and effect the systemic changes required to develop the requisite green skills for the transition to a green economy. In addition to identifying key programmatic interventions, participants also outlined key barriers to green economy capacity-building, including lack of knowledge of the skills requirements of the green economy. The Green Fund's capacity building support will be initiated upon approval of the design by the Mancom.

The RFP processes and variety of stakeholder engagement processes such as the roundtable discussion have provided insights into the emerging green economy landscape of South Africa. Energy, natural resources and waste initiatives appear to be driving the transition to the green economy, while the NGO sector has thus far dominated in the funding allocations of the Green Fund. Private-sector investments are vital in achieving a green economy transformation and engagements with the private sector reflect growing interest in supporting green investments. Co-finance opportunities that display greater risk tolerance, such as development and donor finance, also need to be explored because they are more likely to support green economy initiatives, many of which are still in the early stages of the innovation value chain (Green Fund, Citation2013a).

The lessons that are emerging from the Green Fund portfolio illustrate the potential of public environmental finance instruments to direct and shape the green economy transition of the country. However, when assessed against key criteria for the implementation of EFs, it is clear that there are critical areas that will need to be addressed going forward.

4. Mobilising environmental finance in southern Africa: Lessons from the Green Fund

The Green Fund, operating effectively for close to two years now, will be assessed in relation to the four conditions deemed essential for the functioning of EFs according to the GEF evaluation of EFs (GEF, Citation1999). These conditions were also highlighted in the Handbook of Environmental Funds (Norris, Citation2000) and echoed in more recent studies on EFs. The preceding discussion on the Green Fund's first two years of operation will be drawn upon to assess the Fund's performance in relation to these four critical conditions for the establishment of EFs: a strong governance system, with representation from diverse sectors; long-term financial commitment (10 to 15 years); active government support; and strong legal and financial practices.

While the existing competencies within the governance structures of the Green Fund serve as a safeguard against overlapping mandates of public environmental finance expenditure, its governance structures are currently dominated by public-sector representation. Thualt et al. (Citation2011) caution against this, while WIOMSA (Citationn.d.) specifically advocates that the Board members of EFs should be comprised of a mix of governmental and NGOs, as well as private-sector institutions. The involvement of key stakeholders in the public and private environmental finance space, for instance, could enable environmental and climate finance resources to be targeted in a coordinated manner, building the partnerships required to mobilise investment in South Africa's green economy transition. Critical mass from diverse sectors and stakeholders, civil society organisations in particular, has been identified as one of the success factors for EFs by several other studies (Bayon et al., Citation1999; Thualt et al., Citation2011). Broader stakeholder representation in the governance structures of EFs builds more robust, transparent and inclusive management systems that could serve to demonstrate the judicious management of public funds.

The Green Fund was capitalised with fiscal funding unlike many EFs discussed in the literature review, which were established mainly with private and donor funding. In this way, the Fund is more in line with current trends in environmental and climate finance that promote the use of public funds to leverage and attract private and donor funding (Venugopal & Srivastava, Citation2012; Amin et al. Citation2013). While the Fund was initially envisioned as a medium to long-term financing mechanism (DBSA, Citation2011b; Green Fund, Citation2012a), current fiscal commitment spans a five-year period. Long term commitment, 10 to 15 years, is regarded as a critical factor in the sustainability of EFs (GEF, Citation1999). The Fund therefore has to either secure a medium to long-term fiscal commitment, or reconfigure its portfolio to establish itself as a key player in the environmental and climate finance landscape.

The nature of the financial instruments in the current portfolio of the Fund (i.e. dominance of grant funding) as well as the broad mandate of the Fund has implications for the sustainability of the Fund. For instance, modifying the funding instruments by placing more emphasis on the loan component could facilitate the establishment of the Green Fund on the principles of a revolving fund that could strengthen its sustainability (Green Fund, Citation2013a). Fund prioritisation is another factor that could facilitate long-term fiscal commitment to the Fund. The positioning of the various economic sectors in the Fund's portfolio appears to highlight that key sectors are driving the country's green economy transition. While the thematic funding windows of the Fund were developed from the programme areas in South Africa's green economy policy framework, they were still very broad, making it difficult to make targeted catalytic investments in the first two years of the Fund's operation. Oleas & Barragán (Citation2003:9) state that establishing clear priorities ‘is an essential tool to avoid spreading resources too thin to achieve identifiable impact’ and that these broad focus areas often make it difficult to balance fund portfolios and measure results. Clear funding priorities focused on key sectors, for instance, could be an important avenue for directing catalytic investments, demonstrating impact and thereby building a ‘bankable’ portfolio going forward.

The origins and establishment of the Green Fund demonstrates active government support, one of the key success factors in the establishment of EFs (GEF, Citation1999). The Green Fund emerged within an enabling policy framework, and its initial focus areas and priorities were formulated in relation to the green economy policy priorities of the country (DBSA, Citation2011a; Green Fund, Citation2012a). In this way the Fund is responsive to the national green economy mandate and vision of the country. Fiscal funding, initially allocated over a three-year period, has been extended to five years. Additionally, the growing interest and attendance at the Green Fund's inter-governmental governance structure (Government Advisory Panel) further illustrates active government support for the Fund. While the capitalisation of the Green Fund has led to strong public-sector presence in the governance of the Fund thus far, the GEF study suggests that funds should endeavour to create ‘a mixed public–private sector mechanism that will function beyond direct government control’ (Citation1999:12). Active government support therefore does not equate to state control or monopoly of EFs, but is rather a way to ensure the relevance of the scope and mandate of the EF to the national environmental agenda.

With respect to fund disbursement and delivery, the Green Fund has in the first two years of operation established sound financial and legal principles that have guided investments in green economy initiatives. The Fund has published an Investment Strategy (Green Fund, Citation2013a) and draws upon the systems and processes of the DBSA (including investment appraisals, contracting and auditing), which operates in accordance with international best practices in development finance. The blending of environmental and financial expertise is one of the defining characteristics of environmental finance institutions and the Green Fund is well on its way to building an institution that could play a vital role in accessing, managing and delivering environmental and climate finance in South Africa. This is a vital lesson for the region (and continent), which still has to develop governance structures and systems to effectively deliver environmental finance at the national level (Whande, Citation2011).

While the Green Fund is still in its initial start-up phase, it needs to draw upon the extensive experience in the governance and management of other environmental and climate funds. When evaluated against the four critical criteria of EFs, as outlined by the GEF study in 1999, it fares well in demonstrating active government support and adhering to the legal and fiduciary standards (contracting, disbursement and auditing) required to administer EFs. However, it needs long-term financial commitment to strengthen its leveraging capacity, and also has to bolster its governance processes by involving a broader set of stakeholders from the private and civil society sectors in its governance processes. These are vital lessons, not only for the Fund but for other institutions that are operating and are being formed for the delivery of environmental finance at national and local levels.

5. Concluding remarks

International reports concur that a ‘global green economy transformation will require substantial financial resources’ and that the ‘role of the public sector is indispensable in freeing up the flow of private finance towards a green economy’ (Bowen et al., Citation2009; UNEP, Citation2011:588–589; Amin et al. Citation2013). Public finance institutions in southern Africa, such as the Green Fund, are at various stages of positioning themselves to participate in the global climate and environmental finance landscape. The lessons being drawn from the implementation of EFs can be more impactful when concrete opportunities for exchange are created. This learning has been initiated between South Africa's Green Fund and the Environmental Investment Fund of Namibia, but needs to be expanded considerably. While national environmental finance institutions, such as the Green Fund, should respond to and reflect national environmental and development priorities, they should also strengthen and refine their capabilities by drawing on and sharing the lessons emerging from environmental and climate finance mechanisms.

Acknowledgement

This paper reflects the independent opinion and analysis of the authors and is not attributable to, nor does it reflect the official position of, the Department of Environmental Affairs, Development Bank of Southern Africa or the Green Fund.

References

- Amin, AL, Naidoo, C & Jaramillo, M, 2013. Financing pathways for low emission and climate resilient development. Working Paper on National Financing Pathways, Climate and Development Knowledge Network, London.

- Bayon, R, Deere, C, Norris, R & Smith, SE, 1999. Environmental funds: Lessons learned and future prospects. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Gland.

- Bowen, A, Fankhauser, S, Stern, N & Zenghelis, D, 2009. An outline of the case for a ‘green’ stimulus. Policy Brief, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London.

- DBSA (Development Bank of Southern Africa), 2011a. Programmes in support of transitioning South Africa to a green economy. Working Paper Series 24, DBSA, Midrand.

- DBSA (Development Bank of Southern Africa), 2011b. South Africa Green Fund and financing mechanisms. Unpublished Report, DBSA, Midrand.

- DEA (Department of Environment Affairs), 2010. National climate change response. White Paper, Government Printer, Pretoria.

- DEA (Department of Environment Affairs), 2011. National strategy for sustainable development and action plan (NSSD1) 2011–2014. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- DEA (Department of Environment Affairs), 2012. Environment sector research, development and evidence framework. An approach to enhance sector science–policy interface and evidence-based policy making. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- dti (Department of Trade and Industry), 2010. Industrial policy action plan 2. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- GCRO (Gauteng City Region Observatory), 2011. Green strategic programme for gauteng. GCRO, Johannesburg.

- GEF (Global Environmental Facility), 1999. Experience with conservation trust funds. GEF, Washington, DC.

- Green Fund, 2012a. Landscape report on priorities and opportunities for the Green Fund windows. Unpublished report, DBSA, Midrand.

- Green Fund, 2012b. Application guidelines (first RFP). Unpublished Document, DBSA, Midrand.

- Green Fund, 2013a. Investment strategy. DBSA, Midrand. http://www.sagreenfund.org.za/SiteCollectionDocuments/The%20Green%20Fund%20%20Investment%20Strategy.pdf Accessed 21 November 2013.

- Green Fund, 2013b. Application guidelines (Second RFP). DBSA, Midrand. http://www.sagreenfund.org.za/SiteCollectionDocuments/Application%20Guidelines.pdf Accessed 2 April 2014.

- Green Fund, 2014. Annual Report 2012–2013. DBSA, Midrand. http://www.sagreenfund.org.za/SiteCollectionDocuments/Green_Fund_Annual_Report%20(Final).pdf Accessed 2 April 2014.

- LEDET (Limpopo Economic Development, Environment and Tourism), 2013. Limpopo green economy plan. Limpopo Provincial Government, Polokwane.

- Mahomed, O, 2013. Maurice Ile Durable. Presentation to the United Nations, 1 November. http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/4074durable.pdf Accessed 2 April 2014.

- Naidoo, C, 2013. Case study: South Africa Green Fund design framework. Presentation to the LEDS GP Workshop, Thailand. http://www.e3g.org/docs/Case_study_South_Africa_Green_Fund_Design_Mar_2013.pdf Accessed 2 April 2014.

- Norris, R, 2000. The IPG handbook on environmental funds: A resource book for the design and operation of environmental funds. Interagency Planning Group (IPG), New York.

- Oleas, R & Barragán, L, 2003. Environmental Funds as a Mechanism for Sustainable Development in Latin America and the Caribbean. http://www.katoombagroup.org/documents/cds/redlac_2010/resources/8337.pdf Accessed 30 June 2014.

- Roux, JP, 2013. Rwanda: Pioneering steps towards a climate resilient green economy. Climate and Knowledge Development Network, Climate and Development Outlook, September, issue 8, 1–6.

- Schalatek, L & Bird, N, 2012. The principles and criteria of public climate finance – A normative framework. Climate Finance Fundamentals 1. Climate Funds Update, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, North America.

- Scholtens, B, 2011. The sustainability of green funds. Natural Resources Forum 35, 223–32.

- Thualt, A, Brito, B & Santos, P, 2011. Governance deficiencies of environmental and forest funds in Pará and Mato Grosso. State of the Amazon (19), Instituto Centro de Vida, Alta Floresta.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2009. Catalysing low-carbon growth in developing countries: Public finance mechanisms to scale up private investments in climate solutions. UNEP, Nairobi.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2010. Driving a green economy through public finance and fiscal policy reform. UNEP, Nairobi.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2011. Towards a green economy: Pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication. UNEP, Nairobi.

- Venugopal, S & Srivastava, A, 2012. Moving the fulcrum: A primer on public climate financing instruments used to leverage public capital. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.

- Western Cape Government, 2013. Western Cape Green Economy Strategy Framework. Western Cape Provincial Government, Cape Town.

- WIOMSA (Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association), n.d. Environmental Trust Funds. http://wiomsa.org/mpatoolkit/Themesheets/E4_Environmental_trust_funds.pdf Accessed 2 April 2014.

- Whande, W, 2011. Visioning climate finance institutions: National implementing entities (NIEs) as a basis for strengthened governance structures. Policy Brief No. 2, Regional Climate Change Programme for Southern Africa (RCCP), UK Department for International Development. One World Sustainable Investments, Cape Town.