Abstract

Urbanisation is an important but contested process because of its far-reaching social, economic and environmental implications. The paper explores the relationship between urbanisation and living conditions in South Africa over the last decade. The central question addressed is whether population growth in the main cities has been accompanied by improved living standards, housing and public services. One finding is that employment growth has tended to coincide with demographic trends, which is necessary to reduce poverty. In addition, the provision of urban infrastructure has outstripped population growth, resulting in better access to essential services and reduced backlogs. In contrast, the provision of affordable housing has not kept pace with household growth, so more people than ever are living in shacks. A more comprehensive assessment is required before one can be sure that urbanisation is on a sustainable trajectory.

Urbanisation now has the potential of transforming the developing world … the path to prosperity inevitably runs through cities. (Glaeser & Joshi-Ghani, Citation2013:1)

1. Introduction

Urbanisation presents considerable challenges and opportunities for low and middle-income countries. On the one hand, the growing concentration of the world's population in cities constrained by a lack of financial resources and weak institutional capabilities poses risks of increasing poverty, insecurity, instability and environmental degradation (UN-Habitat, Citation2012; UNEP, Citation2013; World Bank, Citation2013a). On the other hand, history shows that urbanisation also has the potential to transform socio-economic conditions and reduce human vulnerabilities, depending on how well the process is planned and managed (Glaeser, Citation2011; Jha et al., Citation2013; Storper, Citation2013).

The physical form of urbanisation represents an important dimension of efforts to promote sustainability and a greener economy because of its far-reaching implications for the production and consumption of land, resources and energy (OECD, Citation2011; World Bank, Citation2012a; Simpson & Zimmerman, Citation2013). Careful urban development that reinforces proximity between firms and dense human interactions can foster combined benefits or synergies to the economy and environment through improvements in resource efficiency, productivity and innovation (Hodson et al., Citation2012; Robinson & Swilling, Citation2012; UNEP, Citation2012). Unregulated and haphazard urban development with inappropriate infrastructure can damage the integrity of ecosystems and exacerbate environmental risks and resource scarcities. Rapid urban growth accompanied by even faster, road-based sprawl may lock cities into dysfunctional spatial arrangements and worsening air pollution for many decades (UNISDR, Citation2012; World Bank, Citation2013b).

Attitudes towards urbanisation in South Africa are particularly complicated and equivocal, reflecting the legacy of institutionalised racism, urban exclusion and rural deprivation. Pent-up migratory pressures were released when apartheid was abolished, but deep social inequalities and shortages of land and housing have hampered urban integration (NPC, Citation2012; Turok, Citation2014a). Poor communities are forced to live far from jobs and amenities, often in hazardous environments with deficient infrastructure. The government is committed to universal access to affordable basic services, human rights and redistributive social policies, in line with the new Constitution, but it is also inclined to avoid sensitive territorial issues by treating different places even-handedly, whatever their long-term development prospects. Rural areas tend to receive more explicit attention, although various urban initiatives are also emerging (COGTA, Citation2013; Gordhan, Citation2013; National Treasury, Citation2013; Turok, Citation2014a).

The purpose of this paper is to offer a preliminary assessment of the recent trajectory of urbanisation in South Africa. There is a particular focus on the spatial relationship between urban population growth, employment trends and access to housing and basic services. This has been the subject of much public debate and speculation. A persistent strand of popular opinion suggests that urbanisation is excessive and unmanageable, causing illegal land invasions, burgeoning informal settlements, unprecedented housing pressures, overloaded infrastructure and social disorder. An alternative perspective emphasises the potential for urbanisation to lift people out of poverty by boosting economic growth and prosperity, and enabling more efficient delivery of public and private services (CDE, Citation2014).

2. The notion of sustainable urbanisation

Sustainable urbanisation is a loosely defined idea associated with the rural–urban demographic transition in low and middle-income countries. It implies something about the uncertainties, risks and challenges for society and the environment arising from the pace and composition of urban population growth, especially in a context of intensified global competition and climate change. One concern is with the capacity of city-level institutions to manage the accelerating demands upon them for essential services (Collier, Citation2007; Martine et al., Citation2008; UN-Habitat, Citation2010, Citation2012). Another concern is with the fiscal capacity of these economies to fund the considerable costs of urban infrastructure and avoid damaging bottlenecks, traffic congestion and polluted watercourses (World Bank, Citation2013b). A third concern is with the capacity of urban labour markets to absorb a growing, low-skilled, youthful workforce, potentially resulting in the ‘urbanisation of poverty’ (Ravallion et al., Citation2007). Intense competition for scarce jobs and incomes can strain the social fabric, fuel popular unrest and deter private investment (Saunders, Citation2010). In addition, expanding informal economies and informal forms of service provision tend to imply inferior social protection and greater vulnerability. These are among the greatest concerns of hard-pressed governments experiencing rapid urbanisation, especially in Africa (Buckley & Kallergis, Citation2014; UN-Habitat, Citation2014).

In this paper we focus on three features of urbanisation that are particularly significant to South Africa. This approach recognises that environmental issues are deeply intertwined with other challenges facing the country's cities. The three elements are not exhaustive since there are additional dimensions that are relevant, such as the internal spatial form of the city (sprawling or compact), the energy and resource intensity of its growth path (brown or green), and the configuration of material and natural resource flows within the city (linear or circular). Space and data limitations prevent a more comprehensive analysis in the present paper. The three aspects we focus on are as follows:

2.1 The spatial alignment between population and economic growth

The degree of coincidence or mismatch between jobs and population is important for economic efficiency, social equity, ecological impacts and energy consumption from personal travel and other transactions. This is especially important bearing in mind the history of social engineering and distorted spatial development in South Africa. Access to meaningful employment is vital for income security and material well-being by affording the necessities of life in food, clothing and shelter. Decent work also confers self-respect and fulfilment, provides daily routine and sense of purpose, and ensures participation in the affairs of the wider community. The ability of people to obtain employment therefore makes a big contribution to holding communities together (Turok et al., Citation2006).

2.2 The availability and form of essential urban infrastructure

Essential urban infrastructure includes electricity, fresh water, sanitation and refuse collection. These services help to avoid squalid living conditions and give families some of the capabilities to progress. They are part of the foundation for healthy individuals and thriving communities. They also affect the viability of urban economies and help to protect ecosystems from untreated waste and pollution (World Bank, Citation2013a). Hence the future well-being of local communities depends on investment in building and maintaining these ‘public goods’.

2.3 The nature and condition of household shelter

Whether people live in shacks or formal housing has a profound effect on their quality of life and vulnerability to flooding, fires, contagious diseases, landslides and other disasters. Protection from the elements, privacy and security are vital for human survival, dignity and community stability. People living in informal dwellings are most likely to experience hunger, overcrowding and inadequate services (StatsSA, Citation2010). Tenure security can also provide an economic asset that can be mobilised to invest in education or enterprises. Hence, housing improvement is important to transform people's material circumstances and future life chances.

The core question addressed is whether conditions in South African cities have changed for the better over the last decade in terms of sustainable urbanisation. More specifically, has the distribution of jobs and population become more closely aligned, thereby improving access to opportunities and reducing the need for long-distance migration and commuting? Has investment in urban infrastructure made inroads into inherited backlogs and kept pace with household demands in the main cities? And have the living standards of urban residents improved to the extent that they now have greater protection from public health and environmental problems, and assets to fall back on in times of stress?

The evidence is drawn from the 2001 and 2011 Censuses of Population. The Census gives a unique, person-centred perspective on progress towards lasting and shared prosperity in small geographical areas. Census variables are quite broad and unsophisticated, particularly in relation to many environmental and economic concerns, but have the virtue of being relatively robust and widely available at a fine granular scale. Many of them can be treated as useful proxies for wider economic, social and environmental sustainability indicators (UNDESA, Citation2007).

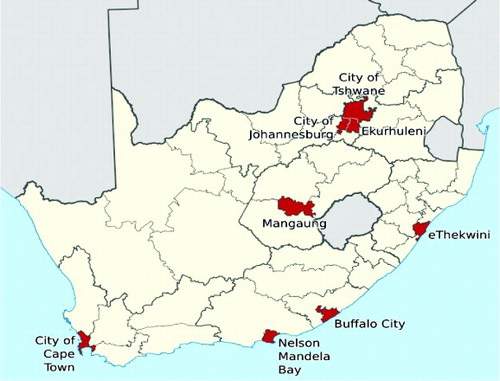

The focus is on South Africa's eight largest cities (), defined according to 2011 municipal boundaries, with the 2001 data adjusted accordingly. These cities are compared against each other and against the rest of the country. Municipal boundaries for these metropolitan areas are reasonable approximations to functional labour market areas because of their large jurisdictions. This reflects the political imperative post-apartheid to incorporate outlying suburbs and dormitory townships with the core cities in order to create the spatial basis for effective strategic planning and resource redistribution against a backcloth of inherited segregation and institutional fragmentation.

3. Population and economic trajectories

South Africa's urban population has accelerated since the 1980s, following the removal of apartheid influx controls (Vacchiani-Marcuzzo, Citation2005; United Nations, Citation2012; Turok, Citation2014a). Growth would have been even stronger without the effects of HIV/AIDS and associated illnesses such as tuberculosis. The significance of urbanisation is apparent from the striking disparity in demographic growth rates between the metros and the rest of the country. Nearly two-thirds (60%) of South Africa's total population increase between 2001 and 2011 occurred in the metros (), which occupy only 2% of the land area. Their average growth rate over the decade was nearly three times higher than the rest of the country.Footnote3

Table 1: Population growth, 2001–2011

The rate of expansion has also been very uneven between the different cities. The fastest increase occurred in two of the Gauteng metros (Johannesburg and Tshwane), followed by Cape Town and the third Gauteng metro (Ekurhuleni). It is striking that over one-half of the country's total population growth between 2001 and 2011 occurred in Gauteng and Cape Town. The rate of increase in the other four metros was much closer to that in the rest of the country.

This uneven pattern translates into very different challenges and opportunities between cities and other places. There is greater strain on public services in the large metros and considerable demand for jobs and livelihoods. A swelling population requires many new schools, clinics and roads, new water pipes, sewage treatment plants, electricity networks and waste-disposal facilities. Rapid demographic growth puts extra pressure on natural water courses, air quality, green spaces, landfill sites and biodiversity, thereby inflating environmental risks and threatening resource scarcity (UN-Habitat, Citation2009; UNISDR, Citation2012; Jha et al., Citation2013; World Bank, Citation2013a).

The relationship between the location of economic growth and where people settle is particularly important, since employment provides the main source of income for household consumption and the key mechanism for social inclusion. Local economic activity is also a major source of revenues for public investment in municipal services. The central question is whether jobs and population have become more closely aligned at the national scale over the last decade, thereby rectifying one of the spatial dislocations inherited from apartheid. This applies particularly to the exclusion of the black population from the metropolitan areas and their concentration in the former Bantustans.

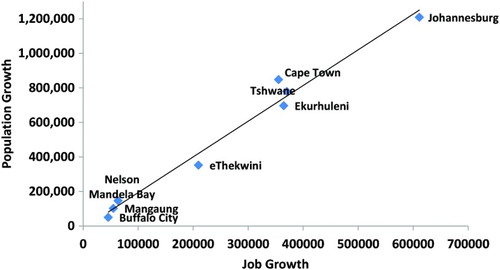

provides a simple indication of this relationship for the eight metros. It shows the scale of population growth on the vertical axis and employment growth on the horizontal axis. The pattern suggests a reasonably strong connection between the trends in jobs and people. Employment growth has broadly kept pace with the scale of increase in people living in the different cities. This is a positive finding from the perspective of sustainable urbanisation because it suggests that the key driver of household livelihoods and public infrastructure funding has tended to coincide with demographic expansion. People appear to be adjusting in a proportionate manner to the uneven growth of economic opportunities across the country. They seem to be moving to where their chances of getting a job are higher, such as Johannesburg. The correlation between employment and population may also stem from the stimulus to jobs caused by higher local demand for consumer goods and services, housing, schools and other public services from demographic growth (Turok & Mykhnenko, Citation2007).

The detailed pattern of employment growth in each metro is presented in . Nearly two-thirds (60%) of the total employment increase in South Africa between 2001 and 2011 occurred in the metros. Their average growth rate over the decade was more than one-third higher than in the rest of the country. The Gauteng metros and Cape Town led the way in terms of the rate of jobs growth, followed some way behind by the smaller metros.

Table 2: Employment growth, 2001–2011

Columns three and five of are also important in showing the proportion of the working-age population (people aged 15 to 65) in each city that were employed in 2001 and 2011. This ‘employment ratio’ in the metros in 2011 was 50% higher than in the rest of the country. In other words, almost one-half of all adults (48%) in the metros had a job compared with only one-third (32%) in the rest of the country. This is a striking disparity, bearing in mind the significance of employment to household and community well-being. Furthermore, the employment ratio increased in every city over the decade, whereas it barely increased in the rest of the country, so the gap between urban and rural areas widened. By 2011, 53% of adults in Johannesburg had some kind of work, compared with one in three outside the metros. Many of those who have been moving to where their job prospects are brighter seem to have succeeded. The Johannesburg labour market appears to have been able to absorb a larger proportion of those looking for work than other places.

The relatively strong growth in employment in the metros was matched by the apparent growth in incomes (). Average household incomes in the metros increased by more (in absolute terms) than in the rest of the country. Average incomes in the metros were much higher to begin with in 2001, and they more or less maintained their advantage over the following decade. The highest average incomes were in Johannesburg, followed closely behind by Tshwane and further behind by Cape Town. An important qualification concerning the 2011 income data is that they are in nominal values (i.e. they have not been adjusted for inflation), but this does not affect the comparisons between places at particular points in time.

Table 3: Average household incomes, 2001–2011

To summarise this section, the population and economic trajectories across South African cities over the last decade have been beneficial from the perspective of sustainable urbanisation and access to opportunities. The scale of jobs and population growth in different cities has more or less coincided. The largest cities have grown more quickly than the smaller cities, towns and rural areas. They have generated more resources to raise living standards and investment in municipal services.

4. Essential urban infrastructure

Strong population growth in the large cities risks out-pacing the ability of municipalities to deliver basic infrastructure and household services. The consequences of a failure to keep pace would include a higher incidence of squalor and misery, greater exposure to health risks and environmental hazards, and more chance of degraded ecosystems from untreated waste and polluted water courses. Informal urban settlements are particularly vulnerable to these hardships because of their very high population densities and typical lack of public facilities.

In fact the evidence shown below suggests that there have been substantial improvements in the availability of basic services in the metros over the last decade. Despite their enlarged populations, the big cities have enhanced their position in terms of service delivery. Progress has been most apparent in relation to piped water, flush toilets and refuse removal.

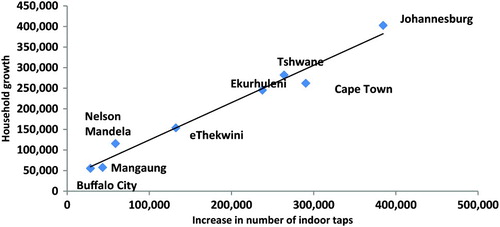

shows the relationship between household growth and access to an improved water source for the eight metros. This is defined here as piped (tap) water inside the dwelling; it excludes communal taps or stand pipes. The close correlation between the absolute growth in households and the increase in indoor taps suggests that the large metros have done well to keep pace with their expanding populations and have not been overwhelmed by demographic inflows. Part of the explanation may be that the Treasury's equitable share funding formula is successfully allocating resources between municipalities to fund basic services in line with the scale of local household growth (National Treasury, Citation2011). The superior capacity of the big metros to plan and execute projects is also important.

The detailed pattern of improved water supply in each metro is presented in . The total number of households in the metros with access to an indoor tap increased by two-thirds (67%) between 2001 and 2011. The sheer scale of the increase was higher in the metros than in the rest of the country, although the rate of increase was lower because the metros were starting from a higher base, with more of their households already having access to an indoor tap in 2001. The Gauteng metros and Cape Town led the way in terms of the scale of delivery of indoor taps, followed some way behind by the smaller metros.

Table 4: Households with an improved water source, 2001–2011

The other interesting feature of is the proportion of households in each city with an indoor tap. Columns three and five show that nearly two-thirds (64%) of households in the metros had indoor taps in 2011, up from 50% in 2001. This was a big achievement, although of course it still meant that more than one-third of households lacked this amenity. In addition, the proportion of households with indoor taps in the rest of the country increased from 21% to 33%. In 2011, access to indoor taps was highest in Cape Town and Nelson Mandela Bay, followed by Johannesburg and Tshwane. The clear message is that each of the big cities has made very considerable progress in delivering an improved water supply to several hundred thousand local families over the last decade. They have absorbed the additional demands made upon them and have been able to reduce their inherited backlogs. There are bound to be substantial benefits from the supply of fresh water to households for their health and general welfare.

The pattern of improvement in sanitation was broadly similar to indoor taps, except that more households had such facilities in 2001, so the rate of increase over the last decade was lower. Improved sanitation is defined in the Census as access to a flush toilet connected to the sewerage system. This may be a shared or communal toilet off-site, which is likely to be why levels of access tend to be higher than for water. The detailed statistics for each metro are shown in . The total number of metro households with access to a flush toilet increased by two-fifths (40%) between 2001 and 2011. The sheer scale of increase was higher in the metros than in the rest of the country, although the rate of increase was similar. The metros were starting from a much better position, with three-quarters of their households having access to this facility in 2001. The Gauteng metros and Cape Town led the way in delivering flush toilets, followed some way behind by the smaller metros. eThekwini, Mangaung and Buffalo City inherited large, poorly serviced, rural hinterlands, so they appear to have had greater difficulty in extending flush toilets to all their communities.

Table 5: Households with improved sanitation, 2001–2011

The improvements in sanitation are bound to have made a positive contribution to health and social conditions in the metros. They are also likely to have reduced the amount of untreated sewage polluting local water-courses, although this also depends on the capacity and condition of sewage treatment plants. The benefit of this form of sanitation is perhaps less clear-cut from the perspective of future water security, since flush toilets use large amounts of water in places where supply can be constrained. Some environmentalists argue that other forms of sanitation would be more benign, especially in informal settlements, where cost recovery and site-specific conditions often complicate water-borne sanitation. eThekwini's modest increase in flush toilets over the last decade is partly attributable to its hilly topography, water scarcity and efforts to experiment with other forms of sanitation (Head of eThekwini Water and Sanitation, personal communication, May 14, 2012). In 2014 eThekwini won the Stockholm Industry Water Award for its transformative and inclusive approach to providing water and sanitation services.

Like sanitation, solid waste disposal is important for the quality of the living environment, and clearing refuse helps to reduce the spread of disease. The relevant Census variable is the number of households with a weekly refuse removal service. The Census does not record the extent to which waste is recycled, composted or converted into energy, rather than dumped in landfill sites. These would be superior sustainability indicators (SACN, Citation2011).

The detailed statistics for refuse removal across the country between 2001 and 2011 are not provided here because of space constraints. The fundamental pattern they reveal is similar to sanitation, with a sizeable increase in refuse removal everywhere, especially in the big cities. The rate of increase was slightly lower in the metros than elsewhere, because more urban households already had this service in 2001. By 2011, 88% of metro households had weekly refuse removal, compared with 43% in the rest of the country. One explanation is that waste collection is more costly in rural areas because of lower residential densities. Improved refuse removal in the metros has put pressure on their landfill sites, many of which lack spare capacity (SACN, Citation2011). More recycling and composting of waste will be required in the future as metro populations continue to grow and consume more.

Electricity is another basic service with considerable benefits for human development. It reduces indoor air pollution from burning fossil fuels for cooking and heating. Power also enables people to study at night, to keep food fresh for longer, to run televisions and computers, to operate small enterprises, and to recharge cell-phones. The key Census variable is the number of households without electricity for lighting. The Census does not record how the power is generated, but it is well known that the vast majority comes from coal-fired power stations (SACN, Citation2011; OECD, Citation2013). This is the main reason why South Africa is the 14th largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world (World Bank, Citation2012b).

Considerable progress has been made to electrify much of the country over the last decade. The gap between the metros and other areas narrowed considerably between 2001 and 2011, with large declines in the number of households with no electricity for lighting (). The biggest metros appear to have made far less progress than elsewhere, but this is deceptive because they have experienced much greater household growth. For every city to have reduced the number and proportion of families without power is a big achievement.

Table 6: Proportion of households with no electricity, 2001–2011

The extension of electricity supply was accompanied by a reduction in the number of households using solid fuels for cooking, including wood, coal and animal dung. These fuels cause indoor air pollution, which has serious consequences for respiratory health and consequently mortality, especially among young children in South Africa (OECD, Citation2013). The number of households using solid fuels for cooking in the metros fell from 143 000 to 60 000 between 2001 and 2011, a decline of 58%. Only 1% of households in the metros now cook with solid fuels. Lack of electricity elsewhere means that more than one in five households outside the metros still use solid fuels.

In summary, the delivery of urban infrastructure over the last decade has improved access to vital public services. A substantially larger number and a higher proportion of urban households enjoy better living conditions than before, despite the underlying population growth. This is consistent with the broader goals of shared prosperity and sustainable urbanisation. Yet a sizeable minority of households still lack essential facilities, so there is little room for complacency.

5. Household shelter

Living in a shack without any security of tenure usually means a precarious existence because people are vulnerable to overcrowding, outbreaks of fire, disease, flooding and other social and environmental hazards (Hunter & Posel, Citation2012; Seeliger & Turok, Citation2014). In contrast, the stability and security of formal housing enhances household resilience to shocks, improves people's health and self-respect, and frees up women's time, which enables them to participate in the labour market and increase their income (Franklin, Citation2011; Collier & Venables, Citation2013). Housing also provides an economic asset that can support livelihood generation, and the construction of housing is a valuable source of employment for low-skilled labour. Therefore, state efforts to improve housing conditions can boost people's living standards and transform the prospects of poor communities.

Urbanisation means that there are more households living in informal dwellings in the metros than in the rest of the country. The absolute number of such households also grew more strongly during the last decade – up by about 100 000 to 1.1 million (). Against this, the proportion of urban households living in shacks fell from 22% to 18%, mainly as a result of determined government efforts to build formal Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) houses on a large scale. Since 1994, 2.7 million free serviced houses have been constructed, which now accommodate one in five South Africans (National Treasury, Citation2013). The reduced proportion of people living in shacks has been an important achievement considering the pace of urbanisation. Therefore, the overall message in terms of the trend in urban housing conditions is mixed.

Table 7: Number of households living in informal dwellings, 2001–2011

Looked at in more detail, the big metros clearly struggled to contain the growth in shack households because their populations increased more strongly than in the smaller cities and towns. The number of shacks in Cape Town grew by over 75 000 (up 53%), compared with 37 000 in Johannesburg (up 17%), 24 000 in Tshwane and only 5000 in Ekurhuleni. The smaller metros managed to reduce the number of people living in shacks in their areas. Cape Town was the only city among the eight examined where the proportion of households living in shacks actually increased.

The increase in households in informal dwellings was mainly accounted for by the growth in backyard shacks. Johannesburg experienced the biggest increase in backyard dwellings, followed by Cape Town and then Ekurhuleni and Tshwane. There are positive and negative aspects to the growth of backyard shacks. They provide people previously living in unauthorised areas with access to shared services and more security, and they help to densify historic townships and new RDP settlements (Lemanski, Citation2009). Public transport and social services can be delivered more efficiently to compact communities. They also increase the supply of affordable rental property and provide a regular source of income to poor households acting as landlords (NPC, Citation2012; Rubin & Gardner, Citation2013; Presidency, Citation2014). Renting backyard space gives the tenants flexibility to move on when their circumstances change, without tying up their assets in fixed property.

These advantages should be set against several difficulties (Borel-Saladin & Turok, Citation2014). The capacity of basic services is already overloaded in many townships. Unplanned growth can push infrastructure networks and electricity distribution systems beyond the tipping point causing collapse. The quality of services under stress is also likely to suffer from more frequent breakdowns and blockages. Furthermore, overcrowded properties can create health problems and spread infectious diseases, especially if the tenants cannot share the fresh water supply and sanitation services in the main dwelling. Overcrowding in confined spaces and the appearance of more squalid conditions can also give rise to social tensions, complaints from neighbours and a growing sense of malaise.

6. Conclusion

Urbanisation is an important process with far-reaching social, economic and environmental implications for South Africa. This paper explores the relationship between urbanisation and household living conditions over the last decade. The main question addressed is whether urban growth has contributed to shared prosperity and is on a sustainable pathway.

The first major finding is that population trends across the main cities have tended to coincide with employment growth patterns over the last decade, producing a better match than before. This is beneficial in terms of access to economic opportunities, bolstering livelihoods, and supporting balanced and self-sufficient development. There is little sign of ‘excessive’ urbanisation in the large cities; that is, growth in the workforce outstripping growth in jobs to a greater extent than in the smaller cities. Yet there remains a serious employment shortfall in all the cities, just as there is throughout the country.

The second major finding is that the provision of urban infrastructure has also kept pace with population growth in the cities. Indeed, infrastructure delivery has generally outstripped urbanisation. Consequently, access to essential services has improved, and a higher proportion of urban households enjoy decent living conditions than before. The largest metros have proved more capable at providing infrastructure than the smaller cities and towns, so their residents tend to be better-off than elsewhere. A sizeable minority of urban citizens are still deprived of basic amenities, so there is no room for complacency.

The third finding is that the building of formal housing has failed to keep up with household growth in the big cities. Consequently, there are about 10% more households living in shacks in the metros than there were a decade ago. The proportion of urban households living in shacks has fallen (by about one-fifth), but the absolute number has risen. Most of the extra households are living in backyard shacks rather than free-standing shacks. These have some advantages in terms of access to services, which need to be set against drawbacks of overcrowding and overloaded infrastructure. Hence the broad message in terms of progress in urban housing conditions is quite mixed.

Further research is required to deepen these findings and to provide a more comprehensive assessment before one can be confident about whether the overall trajectory of urbanisation in South Africa is contributing to lasting and shared prosperity. There are some positive signs of progress, but also many question marks and outstanding concerns. For instance, more analysis of economic and employment dynamics is required to assess both the quality and quantity of the apparent labour market improvements in the cities, including the ease with which rural–urban migrants are able to access urban education and employment opportunities, the obstacles they encounter, and the extent and ways in which they advance their positions over time to build decent livelihoods (Hunter & Posel, Citation2012; Turok, Citation2014b).

Further analysis is also required of urban infrastructure networks, including their durability and environmental impacts, and the financial and technical constraints on their expansion to accommodate new economic activity and historic backlogs. There have been several reports suggesting that many key urban infrastructure systems in transport, energy, water and sanitation are suffering from under-investment and are vulnerable to serious leakages and breakdowns (SAICE, Citation2011; DBSA, Citation2012). There has been a particular concern that political pressures to extend infrastructure networks to new areas have diverted resources from essential maintenance and upgrading of existing systems.

A third area of further research is around comparisons of alternative forms of low-income housing provision, and the relationship between housing and urban land markets. The dominant model of low density, state-funded RDP housing units has proved to be unsatisfactory in several respects. One of the main problems is that it reproduces isolated dormitory settlements on the periphery and locks in an urban form that will be extremely costly and complex to alter (Harrison et al., Citation2008; Bradlow et al., Citation2011; SACN, Citation2011; NPC, Citation2012). Yet alternative incremental and social rental models also face major hurdles (Napier et al., Citation2013). Backyard shacks may provide affordable rental accommodation with access to services at higher densities, but this is unlikely to offer more than a temporary solution to the shortage of urban housing.

Above all, a research agenda around sustainable urbanisation needs detailed analysis of the interactions between the economic, social and environmental dimensions of urban development. The urban realm is inherently inter-connected and requires multi-disciplinary understanding grounded in space and place. The concepts of sustainability and the green economy raise fundamental questions about the relationship between the economy, environment and social conditions, with a tendency to emphasise the co-benefits, synergies and virtuous circles. Of course there are also many trade-offs and costs involved, and detailed research is required to disentangle the dilemmas, identify realistic opportunities to make progress, and help decision-makers to establish appropriate priorities for urban policy.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on research funded by the National Research Foundation (grant number 78644).

Notes

3Note that this is still well below the urban growth rate of most other African countries (United Nations, Citation2012; UN-Habitat, Citation2014).

References

- Borel-Saladin, J & Turok, I, 2014. The growth of backyard shacks in South African cities. Human Sciences Research Council, Mimeo.

- Bradlow, B, Bolnick, J & Shearing, C, 2011. Housing, institutions, money: The failures and promise of human settlements policy and practice in South Africa. Environment and Urbanisation 23(1), 267–75. doi: 10.1177/0956247810392272

- Buckley, R & Kallergis, A, 2014. Does African urban policy provide a platform for sustained economic growth? In Parnell, S & Oldfield, S (Eds.), The Routledge handbook on cities of the global south, pp. 173–190. Routledge, London.

- CDE (Centre for Development and Enterprise), 2014. Cities of hope: Young people and opportunity in South Africa's cities. CDE, Johannesburg. www.cde.org.za Accessed 15 May 2014.

- COGTA (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs), 2013. Towards an integrated urban development framework. Discussion document, Pretoria.

- Collier, P, 2007. The bottom billion. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Collier, P & Venables, A, 2013. Housing and urbanisation in Africa: Unleashing a formal market process. Centre for the Study of African Economies Working Paper WPS 2013-01, University of Oxford.

- DBSA (Development Bank of Southern Africa), 2012. The state of South Africa's economic infrastructure: Opportunities and challenges. DBSA, Midrand.

- Franklin, S, 2011. Enabled to work? The impact of housing subsidies on slum dwellers in South Africa. Unpublished manuscript, University of Oxford. https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=CSAE2012&paper_id=316 Accessed 12 June 2014.

- Glaeser, E, 2011. Triumph of the city: How our greatest invention makes us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. Macmillan, London.

- Glaeser, E & Joshi-Ghani, A, 2013. Rethinking cities: Towards shared prosperity. Economic Premise 126, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Gordhan, P, 2013. Budget speech, Cape Town, 27 February. http://www.info.gov.za/speeches/docs/2013/budget2013.pdf Accessed 3 January 2014

- Harrison, P, Todes, A & Watson, V, 2008. Planning and transformation: Learning from the post-apartheid experience. Routledge, Abingdon.

- Hodson, M, Marvin, S, Robinson, B & Swilling, M, 2012. Reshaping urban infrastructure: Material flow analysis and transitions analysis in an urban context. Journal of Industrial Ecology 16(6), 789–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00559.x

- Hunter, M & Posel, D, 2012. Here to work: The socioeconomic characteristics of informal dwellers in post-Apartheid South Africa. Environment and Urbanization 24, 286–304. doi: 10.1177/0956247811433537

- Jha, AK, Miner, TW & Stanton-Geddes, Z, 2013. Building urban resilience: Principles, tools and practice. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Lemanski, C, 2009. Augmenting informality: South Africa's backyard dwellings as a by-product of formal housing policies. Habitat International 43, 472–84. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.03.002

- Martine, G, McGranahan, G, Montgomery, M & Fernandes-Castilla, R (Eds), 2008. The new global frontier: Urbanization, poverty and environment in the 21st century. Earthscan, London.

- Napier, M, et al., 2013. Trading places: Accessing land in African cities. African Minds, Somerset West.

- National Treasury, 2011. Local government budgets and expenditure review 2006/7–2012/13. National Treasury, Pretoria.

- National Treasury, 2013. Budget 2013: Budget review. www.treasury.gov.za Accessed 3 January 2014.

- NPC (National Planning Commission), 2012. National development plan 2030: Our future – make it work. The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development), 2011. Towards green growth. OECD, Paris. http://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/48224539.pdf Accessed 3 January 2014.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development), 2013. OECD environmental performance reviews: South Africa. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Presidency, 2014. Twenty year review. The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

- Ravallion, M, Chen, S & Sangraula, P, 2007. New evidence on the urbanization of global poverty. Policy Research Working Paper, World Bank, Washington, DC. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2007/04/8178686/new-evidence-urbanization-global-poverty Accessed 14 August 2013.

- Robinson, B & Swilling, M, 2012. Urban patterns for a green economy: Optimizing infrastructure. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi.

- Rubin, M & Gardner, D, 2013. Developing a response to backyarding for SALGA. South African Local Government Association, Pretoria.

- Seeliger, L & Turok, I, 2014. Averting a downward spiral: Building resilience in informal urban settlements through adaptive governance. Environment and Urbanisation 26(1), 184–99. doi: 10.1177/0956247813516240

- SACN (South African Cities Network), 2011. 2011 State of SA cities report. SACN, Johannesburg.

- SAICE (South African Institution of Civil Engineering), 2011. Infrastructure report card. SAICE, Midrand. www.civils.org.za Accessed 3 January 2014.

- Saunders, D, 2010. Arrival city: How the largest migration in history is shaping our world. William Heinemann, London.

- Simpson, R & Zimmerman, M (Eds), 2013. The economy of green cities. Springer, Dordrecht.

- StatsSA (Statistics South Arica), 2010. General household survey series volume II: Housing 2002–2009. Report No. 03-18-01, StatsSA, Pretoria.

- Storper, M, 2013. Keys to the city. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Turok, I, 2014a. South Africa's tortured urbanisation and the complications of reconstruction. In Martine, G & McGranahan, G (Eds), Urban growth in emerging economies: Lessons from the BRICS. Routledge, London.

- Turok, I, 2014b. The resilience of South African cities a decade after local democracy. Environment and Planning A 46, 749–69. doi: 10.1068/a4697

- Turok, I & Mykhnenko, V, 2007. The trajectories of European cities, 1960–2005. Cities, 24(3), 165–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2007.01.007

- Turok, I, Kearns, A, Fitch, D, et al., 2006. State of the english cities: Social cohesion. Department of Communities and Local Government, London.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2012. Sustainable, resource-efficient cities: Making it happen. UNEP, Nairobi.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2013. Integrating the environment in urban planning and management. UNEP, Nairobi.

- UN-Habitat, 2009. Planning sustainable cities: Global report on human settlements 2009. Earthscan, London.

- UN-Habitat, 2010. State of the World's cities 2010/11: Bridging the urban divide. UN-Habitat, Nairobi.

- UN-Habitat, 2012. State of the world's cities 2012/13: Prosperity of cities. UN-Habitat, Nairobi.

- UN-Habitat, 2014. State of African cities 2014. UN-Habitat, Nairobi.

- UNISDR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction), 2012. Making cities resilient report 2012. www.unisdr.org/campaign Accessed 3 January 2014.

- United Nations, 2012. World urbanization prospects: The 2011 revision. Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, New York.

- UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs), 2007. Indicators of sustainable development: Guidelines and methodologies. 3rd edn. United Nations, New York. http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/guidelines.pdf Accessed 4 January 2014.

- Vacchiani-Marcuzzo, C, 2005. Mondialisation et systeme de villes. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Paris.

- World Bank, 2012a. Inclusive green growth: The pathway to sustainable development. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- World Bank, 2012b. World development indicators database. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://databank.worldbank.org/databank/download/GDP.pdf Accessed 5 March 2013.

- World Bank, 2013a. Building sustainability in an urbanising world. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- World Bank, 2013b. Planning, connecting and financing cities – now. World Bank, Washington, DC.