Abstract

South Africa has announced another massive investment plan in infrastructure, amounting to R3.2 billion. This plan takes the guise of a National Infrastructure Plan made up of more than 150 projects clustered into 18 strategic infrastructure projects. Most of these projects consist of long-lived social and economic infrastructures planned to deliver services for many decades. Meanwhile, South Africa is reaching its environmental boundaries and faces a crucial need to reduce the environmental impacts of its development path. Owing to the lump-sum investment the projects represent and the lock-in effects they induce once projects are built, long-lived infrastructure projects have to be part and parcel of the country's decoupling strategy to sustain service delivery over the long term, and thereby support economic growth and service access. This paper seeks to highlight the role that environmental impact assessments and strategic environmental assessments could play in supporting the greening of public infrastructure as a decoupling means for South Africa.

1. Introduction

South Africa has announced a massive investment plan in infrastructure for the coming years, amounting to R3.2 billion. This plan, called the National Infrastructure Plan (NIP), comprises 150 projects clustered into 18 strategic infrastructure projects (SIPs) (PICC, Citation2013). Most of these projects consist of long-lived social and economic infrastructures planned to deliver services for many decades. Meanwhile, South Africa is reaching its environmental boundaries and faces a crucial need to reduce the environmental impacts of its development path. This implies decoupling environmental impacts and the use of natural resources from economic growth (Swilling, Citation2007; UNEP, Citation2011). Because of the lump-sum investment they represent and the lock-in effects they induce once projects are built, long-lived infrastructure projects have to be part and parcel of this decoupling strategy to sustain service delivery over the long term, and thereby support economic growth and service access.

South Africa is seen as a leader in the emerging and developing world when it comes to the environment: the right to an environment that is not harmful to health and well-being is enshrined in the 1996 Constitution (South Africa, Citation1996:1251). Two environmental assessment tools give effect to this right: environmental impact assessments (EIAs), and strategic environmental assessments (SEAs). South Africa is also regarded as a leader in relation to using environmental assessment tools, policies and practices to address sustainability and environmental issues (DBSA, Citation2009).

Based on a literature review, this paper seeks to highlight the role EIAs and SEAs could play in supporting the greening of public infrastructure in South Africa. Section 2 presents an analytical framework for greening infrastructure based on a literature review of green rating systems' analyses. Sections 3 and 4 describe the South African EIA and SEA systems respectively, review their limitations as identified in the literature, and position their respective ability to green public infrastructure. Section 5 reveals implications for the greening of the NIP, and Section 6 concludes on the policy implications of this analysis.

2. The greening of infrastructure: A conceptual framework

According to the South African government, the overall objective of the green economy is to ‘promote sustainable development by decoupling economic growth rates from environmental degradation while improving the quality of life of all, with particular reference to the poorer groups’ (GoSA, Citation2012:4). Recent studies have shown that a long-lasting greening of the economy cannot solely be based on increasing the efficiency of current production and consumption modes; a more ambitious stance is needed that stresses the transformation of the very structure of the economy and society so as to reach a level of decoupling compatible with the environmental boundaries of our planet (Haberl et al., Citation2011; Jänicke, Citation2012; OECD, Citation2013). Consequently, just like infrastructure supports economic growth and access to services (Amador-Jimenez & Willis, Citation2012; Srinivasu & Rao, Citation2013), the greening of infrastructure should support this decoupling process (Corfee-Morlot et al., Citation2012; World Bank, Citation2012).

Infrastructure should then be assessed according to its decoupling power: its ability to reduce the amount of natural resources used to produce economic growth and to delink economic development from environmental deterioration all along its lifecycle (UNEP, Citation2011). A relative decoupling – a lower growth rate of resource use or environmental impact than the economic growth rate – could be achieved through efficiency improvement of conventional infrastructures. Absolute decoupling – resource use and environmental impacts decline irrespective of the economic growth rate – would require transformative innovation leading to the design of alternative infrastructure (Carlsson et al., Citation2013). illustrates some examples of the differences between improved and alternative infrastructures.

Table 1: Example of conventional and transformative infrastructures

This discussion on the role of infrastructure raises two questions: where should environmental assessments intervene in the infrastructure project cycle; and what should be the assessment criteria?

2.1 Environmental assessment in the project cycle

While public infrastructures are intended to provide a dedicated service for decades, resource consumption during the operational phase becomes particularly crucial and complex as it refers to the kind of economy that the dedicated infrastructure supports. A key challenge stems from the need to evaluate long-term, cumulative macro-economic impacts of infrastructure, and the way they influence the structure of the economy. This implies a clear understanding of the long-term development plan of the country. This goes together with the need to consider an integrated approach for infrastructure development and the identification of co-benefits coming from the integration of a set of infrastructures (World Bank, Citation2012). As a consequence, the greening of infrastructure is not solely happening within a classical infrastructure project cycle – design, planning, construction, operation and deconstruction – through the identification of environmental impacts, the definition of an environmental management plan and the monitoring of its application, but, as highlighted by Morrissey et al. (Citation2012), it has to be applied early on in the project cycle, when the identification of alternatives can still be cost-effective and efficient. This rational forms the basis of the conceptual framework ().

2.2 Environmental assessment criteria

The conceptual framework can only be applied according to a clear set of environmental criteria. This means that the decoupling principle has to be unpacked and translated into well-accepted quantitative and/or qualitative indicators (Wilson et al., Citation2007), before being used in all stages of the project cycle (Morrissey et al., Citation2012). This refers to the collection of baseline data for assessing the state of the environment, identifying what the limits are, and defining long-term environmental objectives for achieving the level of decoupling required. Only then could the greening of infrastructure be assessed. This has led to the development of many sustainability rating tools, first in the building sector before addressing other infrastructures (Siew, Citation2013). Sustainability rating tools include the three dimensions of sustainable development – economic, social and environmental. However, only environmental criteria are considered in response to the decoupling challenge. Based on a wide review of sustainability rating tools, Fernández-Sánchez & Rodríguez-López (Citation2010) provide an initial list of 35 environmental criteria that cover the wide spectrum of environmental issues (). The inclusion of this indicator list into the conceptual framework allows us to map the role of EIA and SEA in the greening of infrastructure: where do South African EIA and SEA intervene in the conceptual framework and what greening criteria do they seek to address?Footnote3

Table 2: Indicators for assessing the greening of infrastructure

3. Environmental impact assessment and the greening of infrastructure

EIAs first appeared in the United States in 1969 before spreading internationally (Morgan, Citation2012). In South Africa, EIA was introduced in the mid-1970s as an input to decision-making on a non-mandatory basis (du Pisani & Sandham, Citation2006:709). ‘EIA is a process for assessing the environmental impacts of development actions in advance’ (Glasson et al., Citation1997:452). The objectives of an EIA are:

1/ to establish in advance whether an activity/ project will negatively impact the environment; 2/ to make sure that impact avoidance, mitigation, management and/ or justification measures are undertaken if it is determined that the activity/ project is found to negatively impact the environment.

3.1 Environmental impact assessments in South Africa

In 1997 the first EIA regulations were passed in terms of the Environment Conservation Act of 1989. These EIA regulations were subsequently replaced in 2006 under the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), No. 107 of 1998 – the core piece of legislation that operationalises Section 24 of the 1996 Constitution (South Africa, Citation1996) and which details the environmental protection clause and refers to the sustainable development imperatives of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit – ‘with the aim to address some of the inherent weaknesses of the previous arrangements, such as time delays, ambiguous screening criteria, vague public participation requirements, etc.’ (Retief & Chabalala, Citation2009:55). In August 2010 a new EIA regulation was passed under the NEMA aiming at improving the screening of projects requiring EIAs, in accordance with international best practice.

3.2 Strengths and weaknesses of environmental impact assessments

The EIA procedure is stipulated in the NEMA EIA regulations. The procedure includes a basic assessment report for small-size projects and a scoping and EIA report for larger projects. In addition, activities located in specified geographic areas also require an EIA. The EIA is undertaken by a certified Environmental Assessment Practitioner and involves a public participation process and interactions with the regulating body or competent authority. Once the EIA process is completed in accordance with the requirements of the NEMA, the final EIA report is submitted for approval to the regulating body/competent authority. This includes a draft environment management programme (EMP), the key monitoring tool used to manage the environmental impacts and risks identified during the EIA. In the event that the project is approved, the environmental authorisation is issued by the regulatory body. This includes approval conditions and may require that the EMP be amended. According to the environmental authorisation, the effective management of the project and associated environmental impacts is the responsibility of the project proponent and this task is usually outsourced to an environmental specialist, environmental control officer or consultant who provides audit reports, as per the requirements of the permit, to the regulatory body. The EMP is a legally binding document, critical in the implementation, operational and decommission phases for environmental risk management, monitoring and evaluation.

When compared with our conceptual framework for greening infrastructure, the EIA process and its evaluations revealed some critical elements worth noting to assess the potential green power of EIAs (). Several criticisms have emerged over time about the effectiveness of EIAs.

Firstly, our conceptual framework emphasises the importance of scoping for alternative infrastructure when responding to a service need. Similarly, a key issue in ensuring that the project design, siting and plans are environmentally sound is flexibility and the ability to change or make changes to the project design, plan or siting during the EIA process to provide decision-makers with alternatives instead of one cast-in-stone project. An attempt was made to remedy the issue by requiring that project design, technology and siting alternatives be included in the project proposal that is the subject of the EIA. Some studies developed prior to the 2010 EIA amendments have highlighted that these requirements were often bypassed (Sandham et al., Citation2008a), these requirements were limited to the location of projects (Sandham & Pretorius, Citation2008), the EIAs have tended to be reactive (Todes et al., Citation2009:424) or that irreversible decisions were made long before the environmental assessment takes place (Retief, Citation2010). Whether the 2010 EIA amendments have changed these practices, especially for recent large-scale infrastructure projects, remains to be evaluated.

Secondly, EIAs focused on curtailing negative impacts of projects and are less suited for the maximisation of positive impacts and the inclusion of sustainability and greening elements. Some studies have noted that while the environmental impact reports were good in the description of the project and the environment, the identification of impacts were far less satisfactory (Sandham et al., Citation2008a, Citation2008b). In addition, cumulative and ancillary impacts are not evaluated during the EIA process. The inability has been noted as a long-standing limitation (Lee & Walsh, Citation1992). As a response, the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations 2010, as part of the NEMA of 1998, is ambitious because Regulation 22 asks for ‘a description and assessment of the significance of any environmental impacts, including – (i) cumulative impacts, that may occur as a result of the undertaking of the activity’ (DEA, Citation2010:27). However, the lack of linkages between assessment and management of risks, as previously underscored, is further compounded by the lack of and incorrect contextualisation of certain impacts and issues (Oosthuizen et al., Citation2011), especially when cumulative effects assessment, cost–benefit analysis, lifecycle assessment and risk assessments are considered.

Finally, the compliance of project developers to EIA conclusions and the enforcement of the authorisation conditions and the EMP are of particular importance. Enforcement of environmental laws and regulations is sometimes questioned especially at a local level in South Africa (Du Plessis, Citation2011). EIA has also been identified as not an exception to the rule in specific cases (O’Beirne, Citation2011; Retief et al., Citation2011). A lack of such enforcement, if confirmed beyond these specific cases, would result in unmanaged impacts despite the implementation of EIA. The Department of Environmental Affairs has identified that the follow-up, response and monitoring of the audit reports does not always take place, resulting in the undermining of the EIA process and a false sense of environmental impact mitigation (Hulett & Diab, Citation2002; O’Beirne, Citation2011). This is a critical issue within the environmental risk-mitigation context and has been debated and discussed for quite some time in South Africa (Hulett & Diab, Citation2002; Oosthuizen et al., Citation2011). It is essential that more emphasis is placed on the EMP and monitoring to ensure that the mitigating conditions are implemented.

4. Strategic environmental assessments in South Africa

SEA was first established in the United States in 1969 and aims to ensure that green principals are incorporated at the early stages of the design and planning process so as to meet the strategic development vision of policies, plans and programmes (PPPs). SEA could be viewed as:

a systemic, on-going process for evaluating, at the earliest appropriate stage of publicly accountable decision making, the environment quality, and consequences, of alternative visions and development intentions incorporated in policy, planning, or programme initiatives, ensuring full integration of relevant biophysical, economic, social and political considerations. (Partidário, 1999 quoted in Caratti et al., Citation2004)

However, definitions of SEAs remain context specific and no clear definitions therefore exist.

4.1 Strategic environmental assessments in South Africa

In South Africa, SEAs appeared in the mid-1990s as a response to EIA's limitations, but on a voluntary basis and without formal SEA legislation (Rossouw et al., Citation2000; Retief et al., Citation2008). In 2000 this work led to the publication of the first guidelines for SEAs tailor-made for the South African context (DEAT & CSIR, Citation2000), resulting in South Africa being recognised as a leader in SEA thinking in the developing world (Dalal-Clayton & Sadler, Citation2005). The principles of the NEMA as included in Chapter One of the Act provide for use of SEA in the promotion of sustainable development. One should note that this does not constitute a legal requirement but acts merely to broaden the tools available in the promotion of sustainable development. During the early 2000s, SEAs were integrated into the South African development planning process as non-mandatory tools. In 2000 the Local Government: Municipal Planning and Performance Management Regulations advised that SEAs were to form part of the development process for the development and compilation of spatial development frameworks (South Africa, Citation2000).

Responding to a need to integrate sustainability into the EIA regulations, environmental management frameworks (EMFs) were introduced that provide for the compilation of information and maps which specify the attributes of the environment, including the sensitivity, extent, interrelationships and significance of such attributes that must be taken into account by every competent authority (South Africa, Citation1998). EMFs are often included into SEAs to facilitate the presentation of environmental challenges to decision-makers (Retief et al., Citation2007). Oosthuizen et al. (Citation2011:24) emphasise that an EMF ‘[…] provides spatial planning practitioners with geospatial references of how planning can take the development and protection of natural resources into account’.

In 2004 the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism published a reference text to ‘provide an introductory information source to government authorities, environmental practitioners, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), industry, project proponents, academics, students and other interested and affected parties’ (DEAT, Citation2004:5). Having recognised the lack of successful voluntary integration of SEA and a need for increased consideration of environmental issues and cumulative impacts in the broader development planning context, new SEA guidelines were published in 2007 (DEAT, Citation2007). The 2007 guidelines detail the key elements of the SEA process and highlight the three principle approaches to SEA.

4.2 Strengths and weaknesses of strategic environmental assessments

Partidário's assertion that ‘SEA is still far from a mature stage’ (Citation2011:437) speaks to the experiences evident in the application of SEA within the South African context. Voluntary SEAs make assessment even more difficult due to there being no clearly established procedure. The sentiment surrounding SEA has been that the ‘[i]nitiation of SEAs would arise from the benefits they provide to decision-makers’ (Rossouw et al., Citation2000:221). This was based on the fact that environmental and sustainability considerations were increasingly being introduced into a wide range of policies since 1994, thereby creating a demand for tools such as SEAs. Many SEAs (50 SEAs between 1996 and 2003, 48 private sector and two public sector) were voluntarily developed before the trend stagnated. This voluntary development of SEA expressed the possibility of developing SEAs outside a command and control mechanism.

When compared with our conceptual framework for greening infrastructure, SEA evaluations revealed some critical shortcomings when assessing the potential green power of SEAs ().

First, the focus of an SEA is on delimiting and understanding the context, making it broader; engaging different (not only environmental) perspectives and searching for the option that will create environmental and sustainable contexts within which proposals are sought (Partidário, Citation2007). This is the most critical feature of SEA for the structural transformation of the society and economy, as it allows for moving beyond the integration of environmental constraints towards the identification of opportunities related to the improvement of the environment. However, SEAs conducted in South Africa have not fulfilled the need for credible and comparable SEA outcomes that are necessary when basing decision-making and planning on SEA (Retief et al., Citation2008). SEA expansion has been driven by consultants, in isolation of any decision-making process, and thereby failed to influence either PPPs or the decision-making process (Retief et al., Citation2007).

Secondly, the lack of formal legislation is perceived as an advantage, because it allows for flexibility and adaptability to different contexts (Retief et al., Citation2008); but it can also become vague and confusing due to the lack of structured approach (Retief, Citation2007). Consequently, SEAs end up more as a tool to identify environmental opportunities and constraints around the development of PPPs rather than as a real assessment of PPPs: ‘[t]he application of SEA in South Africa could be considered as merely a glorified information gathering exercise’ (Retief et al., Citation2008:511).

5. Could SEAs and EIAs green the strategic infrastructure projects?

As the two previous sections show, EIAs and SEAs are valuable, complementary tools required for the mainstreaming of sustainable development, and the greening of infrastructure. Strengths and weaknesses specific to the South African context were identified. They could curtail their greening potential. As a result, the relevance of EIA and SEA for the greening of the SIPs remains subject to conditions.

5.1 Linking strategic environmental assessments and environmental impact assessments

The specifics of each SIP and its component projects have not been determined at this stage (). According to the list of sectors covered by the SIPs, most projects correspond to listed activities as per NEMA legislations and therefore will require an EIA.

The Infrastructure Development Act of 2013, which seeks to facilitate the coordination of infrastructure development, states that whenever an environmental assessment is required in terms of an integrated strategic project it must be done in terms of the NEMA, without distinguishing SEAs and EIAs (South Africa, 2014). The Bill has been criticised on many grounds: for curtailing the conduct of environmental assessment by shortening the project approval cycle; for not including environmental challenges at the early stage of the project; or for not providing any incentives to use SEAs (CER, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). The Act failed to correct them. We deliberately focus on the importance of properly linking SEAs and EIAs within our greening infrastructure conceptual framework according to their strengths, and overcoming their weaknesses ().

Table 3: Presentation of the 18 strategic infrastructure projects

SEAs should play a critical role as a PPP assessment tool if carried out at an early stage of design for the various SIPs. The main objective would be to identify and assess infrastructure alternatives to aspirational environmental objectives. This would require SEAs to be much more ambitious in putting assessment of PPPs at the core. This implies making it mandatory to conduct a SEA for each policy, plan or programme conceived by government (Oosthuizen et al., Citation2011), with enhanced clarity on the procedure to avoid confusion while retaining flexibility. The decision-making process should also display a high-level commitment and the capacity for conducting SEA prior to its commencement is a prerequisite (Slunge & Loayza, Citation2012:257).

Owing to South African limited administrative capacities, SEAs cannot be implemented in addition to existing environmental legal obligations and should be used to improve the screening of projects, so as to reduce the number of applications to support efficiency, quality and effectiveness of the EIA system (Retief et al., Citation2011). This would offset costs and delays by enabling savings at the EIA level. EIA reforms should focus on practice – for example, screening of projects, identification of impacts including cumulative effects and enforcement – and not on the legislation to overcome the identified weakness (Morrison-Saunders & Retief, Citation2012).

5.2 Identifying alternatives through strategic environmental assessments

Infrastructure needs for growth and access have been identified by the National Development Plan (NDP), which sets targets for infrastructure spending (NPC, Citation2012). The links between the NDP and the greening of public infrastructure must not be overlooked. A summary of key issues related to the development of the SIPs is detailed in the following.

First, despite the green economy being acknowledged throughout the plan, with a dedicated green economy chapter, the NDP anchors the future of the country on increased exports and improved competitiveness, with an energy–mineral complex playing a central role. The green economy is seen as an additional economic sector (mostly renewable energy), not a driving principle, and therefore is not directly linked to economic growth and poverty reduction. Not surprisingly, none of three scenarios around which the future of the country is framed factor long-term environmental opportunities and constraints. Because the green economy is not part and parcel of the long-term vision, infrastructure needs are hardly related to the green economy (Giordano, Citationforthcoming).

Second, the identification of service needs to support economic growth, and service access is the first step from which any infrastructure plan can be built, while a feedback loop is necessary to allow for regular critical evaluation and subsequent adjustments of the plan. However, there seems to be a flaw in the South African process. The initiation of the NIP can be traced back to October 2009, when the Infrastructure Cluster was set up by the President to improve the coordination of national Departments and to accelerate the development of infrastructure delivery – that is, two years before the release for comments of the first NDP draft in November 2011, which did not mention any SIPs or equivalent. The first document presenting the NIP was eventually released in February 2012; the final NDP was published in August 2012. One would have rather expected the opposite timeline for the NIP to respond to the NDP.

Finally, the transformative power of infrastructure is better served when infrastructures are integrated, so as to create genuine co-benefits (World Bank, Citation2012). This is what the SIPs should be about. However, there were doubts about such a practice because initial SIPS were deemed a mere collection of shovel-ready or planned projects put forward by sectoral departments working in silos, without any SEA or integrated environmental assessment.

The use of SEA in the planning of the SIPs by the Presidential Infrastructure Coordinating Commission (PICC) or the different sectoral departments would have both raised awareness about environmental opportunities and constraints, and made them politically attractive by linking them to economic growth, poverty reduction and job creation. However, there were no real incentives to do so, because the NDP neither placed the green economy at the core of the development path nor included SEAs in the planning process – despite highlighting that the lack of spatial planning was a real drawback. Fostering the integration of SEA into the decision-making process becomes critical. As suggested by Fundingsland Tetlow & Hanusch:

the ‘holy grail’ is a situation where SEA is more closely integrated into the planning process – possibly to the point where there is no longer a differentiation between SEA and planning, where sustainability issues are effectively considered and where SEA ultimately leads to political change. (2012:17)

5.3 Clarifying the greening criteria

Environmental assessments are dependent on: the coverage of laws and regulations – the more comprehensive the set of laws and regulations, the more likely they are to address potentially damaging activities of a project; and their strictness – the more stringent the norms and standards included in laws and regulations, the more precise the baseline information and long-term targets, the more impactful the assessment (as long as laws and regulations are properly integrated into the assessment procedure).Footnote4 links the green criteria to environmental legislations to which environmental assessments may refer. Such a table – more illustrative than comprehensive, since sector-specific legislations are not reported (e.g. energy, mining, etc.) – reflects which environmental issues have been prioritised and which greening criteria have been overlooked. Not surprisingly, resource use arises as the major gap. A first reason could be that regulations about resource use are more likely to be found in specific sectoral legislation; such as, for instance, construction standards included in the national building regulations that regulate energy usage and energy efficiency. Another reason could simply be the lack of consideration for the use of resources, and would call for new initiatives. Other missing criteria are those related to the role of ecosystems – resilience, value, dynamics – and mitigation of and adaptation to climate change.

Table 4: Strengths and weaknesses of SEAs and EIAs for the greening of infrastructure

Table 5: Contribution of EIA to the greening of public infrastructure

The introduction of climate change as a proper component of SEAs has long been neglected (Hacking & Guthrie, Citation2008). However, several criteria have been identified related to both mitigation and adaptation that could become an integral part of any assessment process, as they have been elsewhere (Pope et al., Citation2013). The challenge remains to have them systematically covered (Posas, Citation2011; Fundingsland Tetlow & Hanusch, Citation2012). One option would be the inclusion of resilience thinking as ‘a structured way of looking at complexity, uncertainty and interrelatedness of systems and processes’ (Slootweg & Jones, Citation2011:264). One might then help to clarify the environmental assessment timescale by looking at both the ecological scale of the resources considered and the uncertainties that might affect its long-term availability. In the same way, adaptive infrastructure planning should gain momentum in the planning process for the improved effectiveness of SEAs (Giordano, Citation2012).

Consequently, many criteria are still very loosely considered while debate continues amongst the EA community (Retief, Citation2010). New infrastructure development could in principle be further greened by amending the SEA regulations so as to tighten or augment the rules, norms and standards they contain, and reforming EIA practices. The question is then on what basis this should occur, because most of the norms and standards are rather backward-looking – that is, based on extrapolating the past – rather than turning toward future requirements (Hacking & Guthrie, Citation2006).

5.4 Strengthening the tiered approach in South Africa

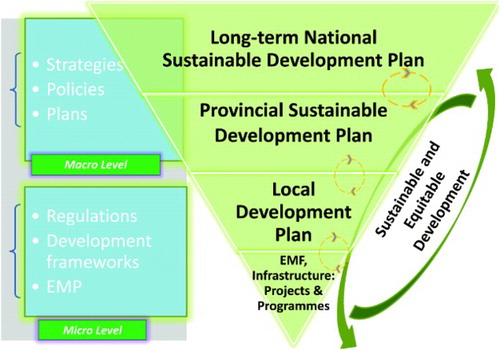

Many SIPs are dealing with different levels of decision–making, like the spatial or geographically linked SIPs. SEA has a critical role to play in this context. Retief et al. (Citation2008:509) argue that ‘SEA was introduced primarily to improve efficiency in a pressured public sector decision-making context, in particular through a tiered system where strategic level environmental information could provide a basis for quick and easy project level decision-making’. This approach needs to be strengthened within the South African context in order to ensure that the most sustainable and least impactful options within the broad SIP framework are to be realised. Such a tiered approach is shown in .

Figure 4: Proposed tiered approach to integrating SEA and EIA into a coordinated approach

The archetype would be informed by the SEA and the development of the overall policy and strategy in the highest tiers. These tiers would then inform the lower or EIA tiers, which would guide the more detailed implementation of the appropriate projects and programmes that would have been identified during the SEA broader planning phase occurring in the higher tiers. The proper coordination of the different tiers is essential, with an ongoing review and evaluation system to ensure that the aims and objectives developed in the higher tiers are being implemented in the lower tiers. If the concept of a tiered approach to SEA and project-level EIA has long been widely accepted, most difficulties reside in its implementation (Rossouw et al., Citation2000).

Given the above, the archetype of a tiered assessment and planning approach to the greening and planning of a programme such as the SIPs should have been guided by a policy appraisal-inspired SEA (Sheate et al., Citation2001). This would have provided a useful baseline and starting point for the subsequent SIP initiatives with regards to the following: risk identification, management and mitigation; the use of green alternatives, design and technologies; and sustainable resource-use options.

It is suggested that the archetype of a proposed tiered assessment model should comprise the following:

At the national level – a national long-term sustainable development plan:

- Developed through a comprehensive national SEA process.

- Providing the baseline and information for the subsequent more detailed assessments that would be required to determine the preferred sustainable development infrastructure options.

At the provincial level – provincial sustainable development plans:

- Integrated and aligned with the provincial development requirements and mandate

- Informed by the comprehensive national SEA process.

At the local government level – a local development plan (LDP):

- The LDP would be similar to existing integrated development plans; however, this plan would have been compiled through a more integrated, strengthened, tiered assessment process, which would hopefully provide the LDP with the required integration, sustainability and green credentials to ensure sustainable development.

- The LDP would be supplemented by an EMF similar to those currently being used within the country. To date ‘there has been limited formal adoption of EMFs as a screening mechanism by environmental authorities’ (Retief et al., Citation2011:167). It is hoped that this proposal will strengthen the adoption of EMF specifically as a screening mechanism.

- The aim of the EMF is to screen and guide planning, location, development and environmental mitigation and management requirements for the infrastructure development and development within the area. This would occur via the use of regulations listing activities and/or projects requiring an EIA.

- These regulations would form part of the EMF and would ensure that infrastructure or developments within the municipal area are aligned with the national long-term sustainable development plan.

- EIAs undertaken for the listed activities and projects would result in project-level EMPs that will guide the construction and operation of the infrastructure.

A strengthened and tiered assessment process commencing with macro national tier assessments and ending with micro local tier assessments would effectively guide and link national priorities to local needs. The Infrastructure Development Act creates a series of institutions – the commission, the council, the management committee, a steering committee per SIP – aimed at the implementation of the NIP (South Africa, Citation2014). Whether this will facilitate the communication and integration between the various tiers of government and ensuring planning and policy integration remains to be seen in practice. Whether the greening of infrastructure will become an integrated part of their functioning is highly uncertain.

6. Conclusion and policy implications

The greening of infrastructure is key for decoupling the economy from natural resource use and environmental impacts. Moving from conventional to innovative infrastructures that support this decoupling is the challenge. This paper has developed a conceptual framework of infrastructure greening and then examined the contribution of SEAs and EIAs to the infrastructure greening process in South Africa. There is a lack of documented information regarding the use of environmental assessment, particularly SEAs, within South Africa. This would require additional work to extensively review recent developments in SEA and EIA practices. However, some preliminary factors can be highlighted:

SEA is key, and should be integrated into a mandatory process through a sustainable planning framework and legislation that are based on clear green principles or criteria. SEAs would then be integrated into the national strategic decision-making process.

Owing to limited environmental assessment and sustainable planning capacity within the country, it is essential that a balance is found where SEAs could be used a screening tool for the development of EIAs. This would reduce the administrative burden on existing regulatory and planning departments.

Environmental assessment should not be seen as an end of process, add-on tool or a threat to decision-making. Environmental assessment should be planned and incorporated into planning from the commencement of the planning process in order to ensure buy-in from departments, agencies or local authorities driving the different SIPs.

A tiered assessment approach would ensure that the multi-level nature of the SIPs and issues that arise are effectively addressed. The PICC and the related institutions, as created by the Infrastructure Development Act, might be able play this role.

Notes

3EIAs and SEAs should be seen as sustainability assessment tools, especially in the South African context where principles of sustainability are entrenched in the 1996 Constitution (Morrison-Saunders & Retief, Citation2012). However, because our focus is on the greening of infrastructure, our analysis is narrowed down to the environmental dimension of sustainability only.

4For instance, some concerns were raised around waste issues being poorly dealt with in some EIAs prior to the 2007 waste Act (Sandham & Pretorius, Citation2008). Proof is still to be found that the Act actually responded to this shortcoming.

References

- Amador-Jimenez, L & Willis, CJ, 2012. Demonstrating a correlation between infrastructure and national development. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 19, 197–202. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2011.644639

- Caratti, P., Dalkmann, H., & Jiliberto, R. (2004). Analysing Strategic Environmental Assessment: Towards Better Decision-making. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

- Carlsson, R, Otto, A & Hall, JW, 2013. The role of infrastructure in macroeconomic growth theories. Civil Engineering and Environmental Systems 30, 263–73. doi: 10.1080/10286608.2013.866107

- CER (Center for Environmental Rights), 2013a. Comments on the Draft Infrastructure Development Bill, 27 March. Center for Environmental Rights, Cape Town.

- CER (Center for Environmental Rights), 2013b. Comments on the Draft Infrastructure Development Bill, B49-2013, 22 November. Center for Environmental Rights, Cape Town.

- Corfee-Morlot, J, Marchal, V, Kauffmann, C, Kennedy, C, Stewart, F, Kaminker, C & Ang, G, 2012. Towards a Green Investment Policy Framework: The Case of Low-carbon, Resilient Infrastructure. OECD, Paris.

- Dalal-Clayton, DB & Sadler, B, 2005. Strategic Environmental Assessment: A Sourcebook and Reference Guide to International Experience. Earthscan, London.

- DBSA (Development Bank of Southern Africa), 2009. What Works For Us – A South African Country Report for Tactics, Tools and Methods for Integrating Environment and Development (A Case Study with the IIED). Development Bank of Southern Africa, Midrand.

- DEA (Department of Environmental Affairs), 2010. National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998) – Environmental impact assessment regulations. Government Notice, Pretoria.

- DEAT (Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism), 2004. Strategic Environmental Assessment. Integrated Environmental Management, Information Series 10. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Pretoria.

- DEAT (Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism), 2007. Strategic Environmental Assessment Guideline. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Pretoria.

- DEAT & CSIR (Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism & Council for Scientific and Industrial Research), 2000. Guideline Document: Strategic Environmental Assessment in South Africa. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Pretoria.

- Du Pisani, JA & Sandham, LA, 2006. Assessing the performance of SIA in the EIA context: A case study of South Africa. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 26, 707–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2006.07.002

- Du Plessis, A, 2011. Environmental compliance and enforcement measures: Opportunities and challenges of local authorities in South Africa. In Paddock, L, Qun, D, Kotzé, LJ, Markell, DL, Markowitz, KJ & Zaelke, D (Eds), Compliance and Enforcement in Environmental Law: Toward More Effective Implementation. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton.

- Fernández-Sánchez, G & Rodríguez-López, F, 2010. A methodology to identify sustainability indicators in construction project management – Application to infrastructure projects in Spain. Ecological Indicators 10, 1193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2010.04.009

- Fundingsland Tetlow, M & Hanusch, M, 2012. Strategic environmental assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30, 15–24. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2012.666400

- Giordano, T, 2012. Adaptive planning for climate resilient long-lived infrastructures. Utilities Policy 23, 80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2012.07.001

- Giordano, T. (Forthcoming). Multilevel integrated planning and greening of public infrastructure in South Africa. Planning Theory and Practice.

- Glasson, J, Therivel, R, Weston, J, Wilson, E & Frost, R. 1997. EIA – Learning from Experience: Changes in the quality of environmental impact statements for UK planning projects. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 40, 451–64. doi: 10.1080/09640569712038

- GoSA (Government of South Africa), 2012. South African inputs to the preparatory processes of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20). http://www.uncsd2012.org/content/documents/368South%20Afric%20Inputs%20to%20the%20United%20Nations%20Conference%20on%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf Accessed 4 August 2014.

- Haberl, H, Fischer-Kowalski, M, Krausmann, F, Martinez-Alier, J & Winiwarter, V, 2011. A socio-metabolic transition towards sustainability? Challenges for another Great Transformation. Sustainable Development 19, 1–14.

- Hacking, T & Guthrie, P, 2006. Sustainable development objectives in impact assessment: Why are they needed and where do they come from? Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 8, 341–71. doi: 10.1142/S1464333206002554

- Hacking, T & Guthrie, P, 2008. A framework for clarifying the meaning of triple bottom-line, integrated, and sustainability assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 28, 73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2007.03.002

- Hulett, J & Diab, R, 2002. EIA follow-up in South Africa: Current status and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 4, 297–309. doi: 10.1142/S1464333202001066

- Jänicke, M, 2012. ‘Green growth’: From a growing eco-industry to economic sustainability. Energy Policy 48, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.04.045

- Lee, N & Walsh, F, 1992, Strategic environmental assessment: An overview. Project Appraisal 7, 126–36. doi: 10.1080/02688867.1992.9726853

- Morgan, RK, 2012. Environmental impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30, 5–14. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2012.661557

- Morrison-Saunders, A & Retief, F, 2012. Walking the sustainability assessment talk – Progressing the practice of environmental impact assessment (EIA). Environmental Impact Assessment Review 36, 34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2012.04.001

- Morrissey, J, Iyer-Raniga, U, Mclaughlin, P & Mills, A, 2012. A strategic project appraisal framework for ecologically sustainable urban infrastructure. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 33, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2011.10.005

- NPC (National Planning Commission), 2012. Our Future – Make It Work: National Development Plan 2030. National Planning Commission, Pretoria.

- O'Beirne, S, 2011. Subtheme 4: Compliance and Enforcement. Department of Environmental Affairs, Environment Impact Assessment and Management Strategy. Environmental Impact Assessment and Management Strategy. Departement of Environmental Affairs, Pretoria.

- OECD, 2013. Putting Green Growth at the Heart of Development. OECD, Paris.

- Oosthuizen, M, Matthys, CHW, Van Weele, G & Roods, M, 2011. Existing and new environmental management tools – Subtheme 9: Quality of tools. Environment Impact Assessment and Management Strategy, Department of Environmental Affairs.

- Partidário, MR, 2011. SEA process development and capacity-building – A thematic overview. In Sadler, B, Aschemann, R, Dusik, J, Fischer, TB, Partidário, MA & Verheem, R (Eds), Handbook of strategic environmental assessment. Earthscan, London.

- Partidário, MR, 2007. Scales and associated data – What is enough for SEA needs? Environmental Impact Assessment Review 27, 460–78. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2007.02.004

- PICC (Presidential Infrastructure Coordinating Commission), 2013. A Summary of the South African National Infrastructure Plan. PICC, Pretoria.

- Pope, J, Bond, A, Morrison-Saunders, A & Retief, F, 2013. Advancing the theory and practice of impact assessment: Setting the research agenda. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 41, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2013.01.008

- Posas, PJ, 2011. Exploring climate change criteria for strategic environmental assessments. Progress in Planning 75, 109–54. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2011.05.001

- Retief, F, 2007. A performance evaluation of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) processes within the South African context. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 27, 84–100. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2006.08.002

- Retief, F, 2010. The evolution of environmental assessment debates: Critical perspectives from South Africa. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 12, 375–97. doi: 10.1142/S146433321000370X

- Retief, F & Chabalala, B, 2009. The cost of environmental impact assessment (EIA) in South Africa. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 11, 51–68. doi: 10.1142/S1464333209003257

- Retief, F, Jones, C & Jay, S, 2007. The status and extent of strategic environmental assessment (sea) practice in South Africa, 1996–2003. South African Geographical Journal 89, 44–54. doi: 10.1080/03736245.2007.9713871

- Retief, F, Jones, C & Jay, S, 2008. The emperor's new clothes – Reflections on strategic environmental assessment (SEA) practice in South Africa. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 28, 504–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2007.07.004

- Retief, F, Welman, CNJ & Sandham, L, 2011. Performance of environmental impact assessment (EIA) screening in South Africa: A comparative analysis between the 1997 and 2006 EIA regimes. South African Geographical Journal 93, 154–71. doi: 10.1080/03736245.2011.592263

- Rivet-Carnac, K, Swilling, M & Giordano, T, (Forthcoming). Greening the national infrastructure programme. In Swilling, M, Musango, JK & Wakeford, J (Eds), Greening the South African economy.

- Rossouw, N, Audouin, M, Lochner, P, Heather-Clark, S & Wiseman, K, 2000. Development of strategic environmental assessment in South Africa. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 18, 217–23. doi: 10.3152/147154600781767394

- Sandham, LA & Pretorius, H. A, 2008. A review of EIA report quality in the north west province of South Africa. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 28, 229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2007.07.002

- Sandham, LA, Hoffmann, AR & Retief, EP, 2008a. Reflections on the quality of mining EIA reports in South Africa. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 108, 701–6.

- Sandham, LA, Moloto, MJ & Retief, FP, 2008b. The quality of environmental impact reports for projects with the potential of affecting wetlands in South Africa. Water SA 34, 155–62.

- Sheate, W, Richardson, J, Aschemann, R, Palerm, J & Steen, U, (2001). Sea and integration of the environment into strategic decision-making, IC Consultant Limited, London. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eia/sea-studies-and-reports/pdf/sea_integration_main.pdf Accessed 4 August 2014.

- Siew, RYJ, 2013. A review of building/infrastructure sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 2, 106–39. doi: 10.1108/SASBE-03-2013-0010

- Slootweg, R & Jones, M, 2011. Resilience thinking improves SEA: A discussion paper. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 29, 263–76.

- Slunge, D & Loayza, F, 2012. Greening growth through strategic environmental assessment of sector reforms. Public Administration and Development 32, 245–61. doi: 10.1002/pad.1623

- South Africa, 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act, No. 108 of 1996. Government Gazette, Pretoria.

- South Africa, 1998. National Enviromental Management Act, No. 107 of 1998. Government Gazette, Pretoria.

- South Africa, 2000. Local Government: Municipal Systems Act, No. 32 of 2000. Government Gazette, Pretoria.

- South Africa, 2014. Infrastructure Development Act, No. 23 of 2014. Government Gazette, Pretoria.

- Srinivasu, B & Rao, PS, 2013. Infrastructure development and economic growth: Prospects and perspective. Journal of Business Management & Social Sciences Research 2, 81–91.

- Swilling, M, 2007. Growth, sustainability and dematerialisation: Resource use options for South Africa 2019. Paper presented at the Workshop on Scenarios for South Africa in 2019, July, Pretoria.

- Todes, A, Sim, V & Sutherland, C, 2009. The relationship between planning and environmental management in South Africa: The case of KwaZulu-Natal. Planning Practice and Research 24, 411–33. doi: 10.1080/02697450903327022

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2011. Decoupling natural resource use and environmental impacts from economic growth. A Report of the Working Group on Decoupling to the International Resource Panel; Fischer-Kowalski, M, Swilling, M, von Weizsäcker, EU, Ren, Y, Moriguchi, Y, Crane, W, Krausmann, F, Eisenmenger, N, Giljum, S, Hennicke, P, Romero Lankao, P & Siriban Manalang, A, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- Walmsley, B & Patel, S, 2011. Handbook on environmental assessment legislation in the SADC region. 3rd edn. Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) in collaboration with the Southern African Institute for Environmental Assessment (SAIEA), Pretoria.

- Wilson, J, Tyedmers, P & Pelot, R, 2007. Contrasting and comparing sustainable development indicator metrics. Ecological Indicators 7, 299–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2006.02.009

- World Bank 2012. Transformation through infrastructure. Infrastructure Strategy Update FY2012-2015, World Bank, Washington, DC.