Abstract

Direct control of mineral resource wealth by communities in resource-endowed regions is advocated as a panacea to conflict and fundamental towards attainment of self-determination and local autonomy. Based on the study conducted in Royal Bafokeng and Bakgatla Ba Kgafela, the two prominent, platinum-rich traditional communities in South Africa's North West Province, this article reveals that, although mineral wealth in South Africa's platinum-endowed communities such as Royal Bafokeng is reportedly distributed ‘in the name of morafe’ (‘community’ in Setswana), inadequate participation produces polarised local priorities and tensions at the grassroots level. Community control of mineral wealth is thus likely to paradoxically generate conflict and exclusion at the traditional community level, particularly in contexts where participation in mineral wealth-engendered community development is championed by traditional leaders through customary-derived spaces of local engagement.

1. Introduction

Studies have shown that the absence of direct communityFootnote2 control of, or meaningful participation in, mineral wealth remains a major factor in the communal resistance and socio-political conflict witnessed in the natural resource-endowed regions of, among others, Nigeria (Ikelegbe, Citation2005), Ecuador (Switzer, Citation2001), Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (De Koning, Citation2008). In the case of Nigeria's oil-rich Niger Delta, for instance, the long history of ‘festering sense of grievance’ and ‘agitation for self-determination and control of the resources of the region’ (Obi, Citation2008:4) by relevant ethnic groups has now turned into violent war against the oil companies and the state. The quest for control is better described through the words of Obi (Citation2008:420), who sees the Niger Delta conflict as rooted in ‘the demand for local autonomy … and control of the natural resources (mainly oil) of the Niger Delta by the indigenes of the region’. It is against the background of such conflict that the idea of community control, as a form of community participation in natural resource economy, has gained much recognition. One prevailing argument is that direct control of natural resources by local communities is an important precondition for equitable utilisation of the natural resource wealth, peaceful co-existence between mining corporations and indigenous communities, and congenial relations between local communities and the state (Mate, Citation2002). However, little is known about mineral resource control at the community level – particularly the interface of mineral wealth and community development.

Such practical and theoretical questions provided an impetus for this article to examine the manner in which community participation in platinum wealth utilisation intersects with the institutional systems of traditional administration – particularly when traditional leaders are the key drivers of mineral wealth-engendered community development.

Empirical evidence for this analysis is drawn from an ethnographic study conducted in 2009 in Royal Bafokeng and Bakgatla Ba Kgafela – the two prominent, ‘platinum-rich’ traditional communities in South Africa's North West Province. These communities enjoy considerable control over their enormous wealth generated from platinum mining, mainly through direct royalties and shareholding partnerships with major multinational mining corporations that operate on their communal lands. As a result, they are experimenting with new ‘corporate’ modes of community and natural resource governance. Such a control of mineral wealth is quite unique.

Both study communities have adopted a more or less similar strategy of investing the profits in communal infrastructure. However, the article demonstrates that, although mineral wealth in South Africa's ‘platinum-rich’ communities like Royal Bafokeng is reportedly distributed ‘in the name of morafe’ (‘community’ in Setswana; Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2009:108), inadequate participation of ordinary community members and polarised local priorities proliferate inequality, tensions and pessimism at the grassroots level. Such findings reveal some paradoxes in the manner in which community participation in platinum wealth utilisation intersects with the institutional systems of traditional administration. I argue that community control of mineral revenues in contexts where traditional leaders are faced with the challenge of championing development is fraught with paradoxes, particularly the dilemma of local tensions, conflict and exclusion of community members at the grassroots level. The notion of ‘community’ itself becomes a mirage and it forms the root cause of the struggles that come with communally-controlled mineral revenues.

The findings presented in this paper compel a shift of analytical focus from conflict as an epiphenomenon of collective community exclusion and deprivation, to conflict as also resulting from collective community inclusion. At the policy level, this work triggers some insights that will assist mineral resource-endowed countries, such as South Africa, in dealing with the challenge of developing appropriate policy frameworks for regulating business and social partnerships between local communities and mining corporations, and relationships within resource-rich communities themselves.

2. Community control and participation

Community control in the current sense refers to collective action by community members in using mineral wealth to determine development programmes and policies that would be implemented to meet their collective needs and priorities (Holden, Citation2005:42). Such a definition accentuates the right of communities to participate in development decisions and benefit from the wealth that accrues from minerals extracted from their ancestral lands (Zongwe, Citation2008:8).

Primarily, the argument in this paper is that there is an empirical vacuum in the community control discourse. While local communities still remain ‘at the receiving end’ of the mineral extraction process (Mate, Citation2002:3), a well-established empirical deductive argument exists which posits that exclusion of local communities from mineral resources (mineral wealth) can produce a conflict (Ikelegbe, Citation2005). In Nigeria, for instance, since the first oil commercial production in the late 1950s, Nigeria's oil economy has been epitomised by extreme neglect of indigenous communities, exploitation and impoverishment of the general populace and degradation of environment (Akpan, Citation2006). Subsequently, national governments, mining companies, policy analysts and various scholars have advocated interventions that are largely informed by the principles and approaches of corporate social responsibilityFootnote3 in order to avoid and avert conflict between local communities and mining companies. Although other strategies have also gained momentum – among others, compensational practices and sustainable development approaches (McLeod, Citation2000:116) – corporate social responsibility seems to be the most advocated approach for reducing negative mine impact and potential conflict in regions where mining takes place (Hamann, Citation2004:278). Then again, it should be cautioned that the corporate social responsibility and other advocated approaches have yielded minimal positive results in curbing and preventing conflict in many mineral resource-endowed states. Instead, these approaches tend to hinder the genuine participation of local communities and other key actors (Hamann, Citation2004:288).

Despite the recent upsurge of mine-labour disputes, contemporary tensions in South Africa's minerals sector, particularly in the rural-based platinum industry, arise mainly out of social and environmental damage caused by mineral extraction activities, coupled with underdevelopment in rural communal areas where mining takes place (Cronjé & Chenga, Citation2009).

Another key challenge in managing relationships in communal areas where mining occurs is that the so-called ‘community’ is not homogeneous, and interests are quite often diverse. As such, identifying the ‘legitimate’ ‘community's voice’ is a daunting exercise (Hamann, Citation2003:248–9). Subsequently, mining corporations in South Africa's rural-based platinum sector have adopted a common practice when engaging with rural residents – one of mainly dealing exclusively with traditional leaders as assumed custodians of rural land and other resources.

Despite the highlighted debates, the extent to which mineral-rich ‘tribal’ authorities are capable of engendering broad-based participation in the utilisation of mineral revenues remains less examined.

The conceptual notion of participation has been at the centre of community-based development discourses for several decades and still remains crucial on modern policy agenda. Some regard participation as a crucial normative objective in devising the needed responses to climate change risks (Few et al., Citation2006:2). The concept has also been applied in the analysis of models of management and planning of forests, in natural resource utilisation and resource conservation and in a plethora of other spheres. Hence, in many spheres, participation has ‘assumed the status of orthodoxy’ (Mnwana & Akpan, Citation2009:283; see also Michener, Citation1998:2105). It is anticipated that ‘when the poor in a community participate in key decision-making processes affecting the utilisation of, say, natural resource wealth, they will eventually become empowered and community resources will become more sustainably and equitably utilised’ (Mnwana & Akpan, Citation2009:283).

Such a logical hypothesis remains less examined – especially within the interface of mineral wealth utilisation and traditional authorities. As such, Ribot cautions that various attempts (by governments and other actors) of promoting ‘local democracy’ through efforts of increasing ‘local people's participation in decision-making’, in light of the ‘recent … spectacular comeback of less-inclusive authorities such as customary chiefs’, paradoxically produce ‘pluralism without representation … a formula for elite capture not democracy’ (Citation2007:44). An unavoidable reality is that local communities generally lack the necessary capacity needed to effectively mobilise and utilise their natural resource wealth and to foster equitable and sustainable community development (O'Faircheallaigh, Citation1998). In South Africa's Royal Bafokeng and Bakgatla Ba Kgafela communities, where accountability for promoting wider participation in mineral wealth-engendered community development has been devolved to traditional modes of governance, impetus exists to interrogate how such participation plays out.

Perhaps due to the malleability and ambivalence of the term ‘participation’, it must be cautioned that in this analysis the concept of participation is applied in the sense suggested by Mulwa (Citation1998:52): ‘a process whereby the marginalised groups in a community take the initiative to shape their own future and better their lives by taking full responsibility for their needs and asserting themselves as subjects of their own history’.

3. Notes on data collection

I spent three months collecting ethnographic data in the Bafokeng villages of Phokeng (the capital territory that many refer to as a ‘town’), Kanana and Ga-Luka (also called Luka), and in the Bakgatla villages of Moruleng and Lesetlheng. The villages were selected either because they are very close to the mines and therefore likely to experience more mining impact than other villages or because they are the capital regions of the study communities and are therefore major population centres and seemingly prioritised target areas of infrastructural development. In-depth interviews were conducted with respondents from both study communities. The key informants that were purposively selected on the basis of their socio-economic status and their role included six senior officials from community-owned corporate entities, two traditional councillors, two retired traditional councillors, two officials from the mining companies, six leaders of village forums and three dikgosana. Footnote4 I also conducted in-depth interviews with 33 residents who occupy or own the plots of land in the villages. This move allowed me to select social categories that are less visible in the traditional leadership structure, particularly women and the youth. Although I broadened my selection of respondents to cater for broader social categories, male dominance in the traditional leadership structure made the selection of male key informants unavoidable at times. This became one of the key limitations in my research approach. presents the distribution of interview respondents.

Table 1: Numerical distribution of interview respondents

Without a doubt, deciding on qualitative sample sizes can be a daunting exercise. I must also caution that my main goal with this modest sample size was not to derive empirical accuracy through representative sample procedures, but rather to interview enough respondents to produce sufficient data for generating rigorous empirical knowledge. Such a goal is premised at the centre of grounded theory's empirical strategy of ‘data saturation’.

Other primary data collection methods were unstructured observations and community bulletins and corporate reports.

4. The platinum boom and ‘communities’

The platinum mining industry in South Africa has recently emerged ‘to a position of increasing dominance at the heart of the post-apartheid mining economy’ (Capps, Citation2012a:64), thanks to the recent upsurge in demand for platinum group metals and rising platinum prices as from the late 1990s. The economic gains from the platinum industry are phenomenal and the future seems bright. Some analysts have even argued that ‘South Africa could and should become the first mover in creating a kind of “Platinum Valley” that emulates the great Silicon Valley success of the US’ (Creamer, Citation2012:1).

Over the last two decades the platinum industry has been characterised by anomalous, lucrative transactions between mining companies and traditional communities on whose ancestral lands platinum extraction occurs. As a result, some traditional communities on the land that spreads over the platiniferous Bushveld Complex are actively participating in massive platinum windfalls as recipients of mining royalties and shareholders. The case of Bafokeng and Bakgatla communities in the North West Province epitomises this phenomenon. In fact, the Bafokeng community is unparalleled by any other traditional community in South Africa in terms of mineral wealth control and diversified corporate investments.

Essentially, the inclusion of traditional communities in South Africa's platinum industry is embodied within the post-apartheid state's minerals legislation – particularly the commitment ‘to transform the racial structure of mine ownership’ in the country (Capps, Citation2012b:330) through the Black Economic Empowerment mine–community transactions and the quintessential encouragement (by the state) of communities who previously received royalty compensations for loss of land due to mining to ‘convert’ their ‘interests … into equity’ shares (Manuel, Citation2008:3). As such, the dominant mode of engagement between traditional communities and mining companies is through local chiefs – ‘mining companies enter into contracts with the traditional leaders, on behalf of their constituencies’ (Manson & Mbenga, Citation2012:110). Such a phenomenon illustrates the entrenchment of the powers of traditional leaders over rural citizens in post-apartheid South Africa, which has been formalised through the enactment of the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act 41 of 2003 and other subsequent pieces of legislation. Seemingly, this legislation undermines rural citizen's rights over land resources and has been criticised for revitalising ‘key colonial and apartheid distortions which exaggerate the power and status … traditional leaders in relation to land’ and ‘reinforce[s] patriarchal power relations’ (Claassens, Citation2005:3).

The institution of traditional leadership, seen by some as a product and instrument of colonial administration's ‘indirect rule’ mechanism that was created to rule Africans as mere subjects not citizens (see Mamdani, Citation1996), has ironically risen to prominence in post-apartheid South Africa – to the level of championing mineral wealth-engendered community development. Ntsebeza (Citation2006:15) also finds it paradoxical that the post-apartheid government promotes constitutional rights and principles of democracy while simultaneously endorsing and revitalising the role of ‘unelected’ traditional leaders over the country's vast rural citizenry.

Therefore, it is behind this extraordinary nature of traditional elite-mediated community control of mineral wealth that this article examines the manner in which community participation in platinum wealth utilisation intersects with the institutional systems of traditional administration in mineral-rich rural communities – the Bafokeng and Bakgatla, in particular.

5. The study communities: Bafokeng and Bakgatla

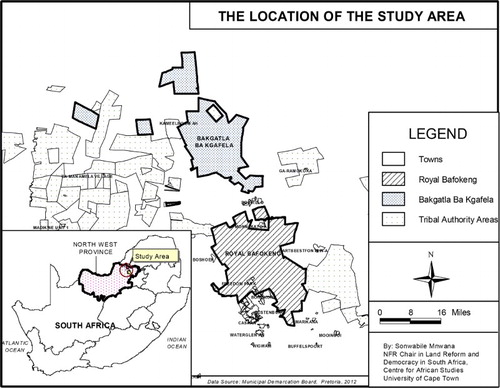

The Bafokeng community, now rebranded as the Royal Bafokeng Nation (RBN), is a leading traditional community in South Africa in terms of corporate investments and control over mineral revenues. The Bakgatla Ba Kgafela community seems to be following suit. Residents in both study communities are mainly Setswana speakers. The Bafokeng and Bakgatla communities fall under the Rustenburg and Moses Kotane Local Municipalities, respectively. Community participation in these communities is engendered through traditional institutions of community governance. The traditional structure of governance in the two communities displays strong similarities. At the top echelon of power in both communities sits the Kgosi (Setswana term for chief or king). Under the Kgosi there are hereditary, male ‘headmen’ who automatically occupy the positions vacated by their fathers, dikgosana (kgosana). Kgosi Nyalala Pilane is the current leader of Bakgatla Bakgafela in South Africa. The current Kgosi of Bafokeng is Kgosi XVI Leruo Tshekedi Molotlêgi (see for a map of the study area).

The Bafokeng territory is divided into 72 dikgoro (singular: kgoro), traditional/tribal wards made up of various clans each headed by a kgosana. The 72 dikgoro make up the 29 villages of the Bafokeng. The constitution of these clans is complex: in the case of the Bakgatla ba Kgafela, 32 dikgosana preside over 32 villages, while the Bakgatla have only five dikgoro.

Bafokeng and Bakgatla people are historically agro-pastoralists who survived mainly through farming (Schapera with Comaroff, Citation1953:14–5, 72–3; Makgala, Citation2009:21–8). The unique control of mineral wealth in these traditional communities bears some historical trajectories that are mainly underpinned by dynamics around colonial struggles around dispossession and ‘regaining’ of indigenous territories – land. The question of land ownership by the two communities is highly complex and elusive since most historical accounts of the subject tend to differ.

Both communities have historically received royalties from mining companies operating on their ancestral lands, albeit in insignificant quantities. Although the Bafokeng started receiving revenues in the 1970s, the amounts were negligible until 1999 when the community won a significant legal battle against Impala Platinum (Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2009:101). Bakgatla have also been receiving mining royalties from Anglo Platinum (Aplats-Union Section) since 1982. These royalties have been converted into equity stakes (shares) in line with the post-apartheid mineral legislation.

The significant equity stakes with ‘platinum giants’ such as Anglo Platinum and Impala Platinum have distinguished these two from other traditional communities in South Africa in terms of their positioning in the mineral wealth economy.

Both communities still depend largely on platinum mining investments. The Bafokeng, in particular, have investments in, among others, the telecommunications, financial and manufacturing sectors, although they are still largely dominated by mining investments. Indeed, as Comaroff & Comaroff (Citation2009:106) caution, ‘it is hard to keep up’ to track with these investments. The key mining investments of the study communities, recorded mainly between 2008 and 2009, are presented in .

Table 2: Key mining investments

6. ‘In the name of morafe’?

This section, through an analysis of in-depth interview narratives, provides an empirical discussion on the paradoxes of participation that arise at the interface of the institution of tradition and the modern community development arena bolstered by the platinum mining economy in the study communities. With regard to the platinum wealth distribution model adopted by the Bafokeng community, anthropologists Comaroff and Comaroff point out that:

the strategy of the Royal Bafokeng Nation has not been to distribute its income on its ethno citizenry … It has, instead, invested it and spent it in the name of morafe.

6.1 Community development: Elite vision and ‘imagined’ participation

The commitment to development is expressed through vision documents and sophisticated plans for infrastructural development. The leaders showed enthusiasm about their development plans. A director in one of the units of the Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Administration explained in detail how the Administration had, among other things, established a holding company, built a sports stadium and was constructing a 12-megalitre water reservoir on which R22 million had been spent (Interview, Moruleng, August 2009).

The Bafokeng community has what it calls Vision 2020, or the 2020 Vision, which states that:

We the Bafokeng Nation, the Supreme Council and Kgosi, are determined to develop ourselves to be a self-sufficient Nation by the second decade of the 21st century1.

The study encountered what seemed like an impasse with regard to community perceptions about the development visions. At the grassroots level the narratives revealed some contradictions. The in-depth interview responses exposed a knowledge gap between the leaders and ordinary community members concerning what the community development plans entailed. Responses of community members revealed both a lack of understanding of the participatory process and a sense of distance from the overarching visions and infrastructural development plans. At the very root of this impasse was the non-involvement of ordinary community members during the formulation of community development plans. Some of the responses were as follows:

I personally did not participate in the planning. I don't know who else participated in moulding that particular plan [the Masterplan]. I have never heard of anyone who participated. Models were put in front of the community [by the leaders] to say ‘look this is what we have planned’. You cannot plan for people without involving them in that particular plan. You will find that your plan is not their area of priority …

There is a sense of arrogance on the side of the tribal authorities; when they are doing a development project in a community they seem to think they are doing that community a favour. It is wrong for any authority whether it is a tribal or a local governmental authority to sit in a boardroom and determine what the needs of the communities are … The projects that they are doing were never identified by Bakgatla Ba Kgafela community … It is this community that must determine what their needs are and … priorities are …

At the very heart of this dilemma lies the fact that participation in decisions on distribution of mineral wealth was mainly through spaces or platforms created by virtue of custom – a phenomenon that, according to many local residents, was a hindrance to effective participation. The main participatory platform was the bi-annual AGM-style mass meeting called the kgotha kgothe. So prominent is the kgotha kgothe that analysts and commentators have described it as ‘something of a modern-day Ecclesia, where decisions affecting the community are taken’ (Mnwana & Akpan, Citation2009:286), and ‘a forum of public oversight: in the long-standing spirit of indigenous democracy … like a corporate shareholder meeting’ (Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2009:106–7). One commentator, Sikakhane, after observing the kgotha kgothe proceedings in Phokeng in October 2009, lauded this customary meeting as ‘democracy in action’ – an archetype of democratic practice of accountability from which the ANC government in South Africa should learn a valuable lesson (Sikakhane, Citation2009:1).

Sikakhane's comments could sound reasonable, especially since they are derived solely from subjective observations made during the kgotha kgothe proceedings. However, if one begins to question the extent to which such a platform of engagement enables grassroots ‘voices’ to influence decisions about platinum wealth utilisation, paradoxes could unravel. The narratives drawn from the in-depth interviews with ordinary residents about participation during kgotha kgothe meetings revealed a different picture from the one shown by Sikakhane and other analysts.

The kgotha kgothe as a key participatory platform presented some problems. Among the key paradoxes presented by this form of engagement was the apparent sense of frustration mainly because in these meetings, although they are inclusive platforms, there is very limited room for grassroots ‘voices’. This form of engagement also encouraged elite dominance through highly technical language used in the kgotha kgothe reports and lopsided deliberations, mainly in the form of expert reporting by the leaders of community-owned business entities. With regard to the customary forms of representation, the youth expressed conspicuous displeasure with the manner in which they were excluded from governance and platinum wealth benefits. Moreover, representation by dikgosana in the Supreme Council and other key decision-making platforms made effective participation in community development decisions impossible. Most dikgosana lacked sufficient education to fully comprehend the highly sophisticated, technical and intellectually demanding decisions that pertain to mining contracts and other business partnerships. This dilemma of a weak grassroots ‘voice’ and lethargic representation rendered community participation, at best, ‘tokenistic’. Compounding this dilemma was the frustration expressed by community members, particularly in the Bafokeng community, about the domination of the kgotha kgothe by the hired white experts who are in charge of community business investments. The following is how one interview respondent expressed this finding:

To be honest with you, the Bafokeng wealth and businesses are being controlled by ‘white’ people and not us. They decide on their own and then develop reports … The language they use is too technical and it needs experts who understand them … The majority of people who attend kgotha kgothe are illiterate …

As I have told you before, we are led by dictators. During our last kgotha kgothe meeting we were arrested because we tried to prevent Kgosi Nyalala from taking decisions on our behalf.

We used to demand to know the value of our assets and royalties. We discovered that if we divided the amount of royalties, each Mofokeng household would receive R10 000. We suggested that in every four year period that amount be given to Bafokeng for as long as we still have mineral resources. We said that we can use the clans to account for every family. Each clan would come up with the number of households for administrative purposes. The clans can decide to buy farms, cattle or invest. We could also help manage families with irresponsible parents. We thought that if we used that method we would reach everybody. Kgosi was not pleased with us. This money belongs to community but he [Kgosi] and his family use it as they please … The world still considers us as the richest tribe but we have people among us who are very poor.

Table 3: Royal Bafokeng expenditure for 2009 and budget for 2010

shows that in 2009 a meagre 1% of Bafokeng's annual budget was spent on local economic development and the same for food security, while massive allocations of the total expenditure (totalling over R1 billion) went towards sports and infrastructure. As described above, the fixation (see ) of local leaders with physical infrastructural development did not resonate well with community members at the grassroots. It is no surprise that this study found discontent at grassroots in the study communities: the priorities are clashing.

Table 4: Bakgatla Baga Kgafela platinum wealth distribution priorities for 2009/10 period

There is no doubt that the rapid infrastructural developments in Phokeng and Moruleng highlight the benefits of platinum mining in the Bafokeng and Bakgatla communities, a feature that distinguishes both communities from the rest of more than 800 traditional communities recognised by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. However, the ownership of mining interests and other corporate interests has discontent at the grassroots level, partly due to what may be termed ‘infrastructure fixation’: there is a clear neglect of the ‘softer’ developmental issues such as food security and economic empowerment for the struggling majority. It is behind the backdrop of such lack of an effective grassroots voice and polarised priorities that local tensions ensued.

6.2 Elite-targeted grassroots anger

The dilemma of polarised priorities was compounded by high tensions about distribution of mineral wealth and the alleged corruption of leaders. The analysis of dominant narratives also revealed heightened popular discontent with the manner in which the traditional leaders handled platinum wealth-engendered community development in the study communities. Community agitations about lack of broader consultation, arrogance and corruption of the ruling elite were rife. Such discontents were marked by sporadic outbreaks of local conflicts in the form of protest marches, disruption of community meetings leading to arrests and court interdicts against certain groups, and even litigation against traditional leaders for alleged corruption.

In the Bafokeng community, for instance respondents felt that there was elite control of their platinum wealth and people from outside, mainly the ‘whites’, who hold key positions in the community-owned investment and development entities, are the major ‘power-holders’ (Arnstein, Citation1969) who take important decisions on behalf of the community. One female respondent explained:

We only see ‘white empowerment’ in Phokeng. The government in South Africa is coming up with strategies of reversing white empowerment in the country, but in Phokeng, it's the opposite. The majority of beneficiaries to date are white …

Nowhere were tensions and allegations of corruption against leaders rifer than in Bakgatla area. Despite the widespread disputes and contentions over the legitimacy of Kgosi Nyalala Pilane's chieftaincy, the issues at the root of discontent in Bakgatla villages were twofold: the poor consultation of community members about utilisation of platinum wealth, and the widespread allegations of corruption against Kgosi Nyalala Pilane and his Traditional Administration. So far, the charges of fraud laid against the chief (Kgosi Nyalala) have not yet deterred control over Bakgatla's vast mineral wealth nor his involvement in community development projects – much to the dismay of many community members, including his political ‘enemies’ who have long called for the North West provincial government to remove him from power. This is how one of the residents expressed her frustration about the matter:

Ever since we took him [Kgosi Nyalala] to court and he was charged with several counts of fraud and corruption he has never called a kgotha kgothe meeting to discuss the outcome of the court with us as morafe … never! While we were waiting for him to come and report the outcome of the court to us … he never did that …

7. Conclusion

The findings presented in this paper contradict the mounting perception that ‘communities are benefiting from mining’, particularly communities that receive direct mining revenues. Patel and Graham, for instance, observe that the Bafokeng community has through the mining revenues established:

[o]ne example of a very successful community trust … [which] has helped the community develop a clinic, schools, early childhood development centres …

The highlighted dilemma signifies lack of accountability and weak external and internal checks on powers of the traditional elite. Evidently there is limited role played by the state in South Africa to monitor and even regulate the manner in which the leaders of traditional leaders who enter into mining contracts receive revenues on behalf of rural communities. It is against the backdrop of this impasse that I recommend some policy intervention. Just as the municipalities are expected to facilitate broad-based participation before deciding on community development priorities, so should the traditional authorities who champion mineral-led community development. Power holders in the traditional arena cannot be allowed by law to become ‘loose canons’. The state should also develop a detailed policy guide with key areas on which resource-rich traditional authorities should report on how they utilise their mineral revenues.

The clamour for resource control by local communities in mineral resource-endowed regions is advocated as a panacea to local conflict. This article has revealed the reverse side of the coin – the dilemmas that surface when local communities are exposed to the challenge of distributing mineral resource wealth. The advocates of resource control should at least be cautious of such paradoxes and appreciate that engendering broad-based community participation in collective utilisation of resource wealth can expose resource-rich communities to dilemmas that render the idea of resource control less fulfilling when held against its reported promises, particularly in contexts where community participation in mineral-led development is championed by traditional leaders through lopsided spaces of local engagement.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge and thank the National Research Foundation Research Chair in Land Reform and Democracy at the University of Cape Town, which made this work possible to accomplish through its generous financial support.

Notes

2‘Community’ in this context refers to residents within territorial boundaries of the study sites.

3Corporate social responsibility in this context refers to the commitment by the mine to take the responsibility of practising socially responsible business practices towards the local communities.

4Hereditary headmen who inherit this position from their fathers; singular, kgosana.

5In the RBN documents, ‘Master Plan’ is written as ‘Masterplan’.

References

- Akpan, W. 2006. Between responsibility and rhetoric: Some consequences of CSR practice in Nigeria's oil province. Development Southern Africa 23(2), 223–40. doi: 10.1080/03768350600707488

- Arnstein, SR, 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 35(4), 216–24.

- BBK (Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Authority), 2009. Investments and projects. http://www.bbkta.co.za/ Accessed 12 January 2010.

- Capps, G, 2012a. Victim of its own success? The platinum mining industry and the apartheid mineral property system in South Africa's political transition. Review of African Political Economy 39(131), 63–84. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2012.659006

- Capps, G, 2012b. A bourgeois reform with social justice? The contradictions of the Minerals Development Bill and black economic empowerment in the South African platinum mining industry. Review of African Political Economy 39(132), 315–33. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2012.688801

- Claassens, A. 2005. The Communal Land Rights Act and Women: Does the Act Remedy or Entrench Discrimination and the Distortion of the Customary? School Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), University of the Western Cape, Cape Town.

- Comaroff, JL & Comaroff, J. 2009. Ethnicity, Inc. The Zulu Kingdom Awaits You. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

- Creamer, M, 2012. Kell Technology Ignites Industry – Creating Hopes for Platinum Sector. http://www.miningweekly.com/print-version/kell-technology-ignites-industry-creating-hopes-for-platinum-sector-2012-04-13 Accessed 15 April 2012.

- Cronjé, F & Chenga, CS, 2009. Sustainable social development in the South African mining sector. Development Southern Africa 26(3), 413–27. doi: 10.1080/03768350903086788

- De Koning, R, 2008. Resource–conflict links in Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo. SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security 2, 1–12.

- Few, R, Brown, K & Tompkins, EL, 2006. Public participation and climate change adaptation. Working Paper 95, Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research.

- Gaventa, J, 2005. Reflections on the uses of the ‘Power Cube’ approach for analyzing the spaces, places and dynamics of civil society participation and engagement. CFP Evaluation Series 4. http://www.partos.nl/uploaded_files/13-CSP-Gaventa-paper.pdf Accessed 15 April 2011.

- Hamann, R. 2003. Mining companies’ role in sustainable development: The ‘why’ and ‘how’ of corporate social responsibility from a business perspective. Development Southern Africa 20(2), 237–54. doi: 10.1080/03768350302957

- Hamann, R. 2004. Corporate social responsibility, partnerships, and institutional change: The case of mining companies in South Africa. Natural Resources Forum 28, 278–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00101.x

- Holden, WN, 2005. Indigenous peoples and non-ferrous metals mining in the Philippines. The Pacific Review 18(3), 417–38. doi: 10.1080/09512740500189199

- Humphreys, M. 2005. Natural resources, conflict, and conflict resolution: Uncovering the mechanisms. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 49(4), 508–37. doi: 10.1177/0022002705277545

- Ikelegbe, A, 2005. The economy of conflict in the oil rich Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Nordic Journal of African Studies 14(2), 208–34.

- Makgala, CJ, 2009. History of Bakgatla-baga-Kgafela in Botswana and South Africa. Crink, Pretoria.

- Mamdani, M, 1996. Citizen and Subject. Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Manson, A & Mbenga, B, 2012. Bophuthatswana and the North-West Province: From Pan-Tswanaism to mineral-based ethnic assertiveness. South African Historical Journal 64(1), 96–116. doi: 10.1080/02582473.2012.648767

- Manuel, T, 2008. Minerals and Petroleum Resources Royalty Bill. http://www.polity.org.za/article.php?a_id=136668 Accessed 6 January 2009.

- Mate, K, 2002. Communities, Civil Society Organisations and the Management of Mineral Wealth. Mining Minerals and Sustainable Development (MMSD). http://www.naturalresources.org/minerals/cd/docs/mmsd/topics/communities_min_wealth.pdf Accessed 15 April 2009.

- McLeod, H, 2000. Compensation for landowners affected by mineral development: The Fijian experience. Resources Policy 26, 115–25. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4207(00)00021-0

- Michener, VJ, 1998. The participatory approach: Contradiction and co-optation in Burkino Faso. World Development 26(12), 2105–18. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00112-0

- Mnwana, SC & Akpan, W, 2009. Platinum wealth, community participation and social inequality in South Africa's Royal Bafokeng community – A paradox of plenty? Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Gold Coast, QLD, 283–90.

- Mulwa, W, 1998. Participation of the grassroots in rural development: The case of the development education programme of the Catholic Diocese of Machakos, Kenya. Journal of Social Development in Africa 3(2), 49–65.

- Murshed, SM, 2002. Conflict, civil war and underdevelopment: An introduction. Journal of Peace Research 39(4), 387–93. doi: 10.1177/0022343302039004001

- Ntsebeza, L, 2006. Democracy Compromised. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Obi, CI, 2008. Enter the dragon? Chinese oil companies & resistance in the Niger Delta. Review of African Political Economy 35(117), 417–34. doi: 10.1080/03056240802411073

- O'Faircheallaigh, C, 1998. Resource development in indigenous societies. World Development 26(3), 381–94. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10060-2

- Patel, L & Graham, L. 2012. How broad-based is broad-based black economic empowerment?. Development Southern Africa 29(2), 193–207. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2012.675692

- RBH (Royal Bafokeng Holdings), 2011. Royal Bafokeng Platinum. http://www.bafokengholdings.com/b/inv_min_br.asp Accessed 19 July 2011.

- RBN (Royal Bafokeng Nation), 2007. Masterplan document. Royal Bafokeng Masterplan: On Target for 2035 – Building for a Better Future for All. http://www.bafokengholdings.com/a/files/RBH_materplan_oct07.pdf Accessed 12 January 2009.

- RBN (Royal Bafokeng Nation), 2009. Kgotha Kgothe Report, October. Royal Bafokeng Administration, Phokeng, South Africa.

- RBN (Royal Bafokeng Nation), 2010. RBN Annual Review Speech by Kgosi Leruo Molotlegi, 18 February, Phokeng, South Africa. http://www.bafokeng.com Accessed 10 July 2010.

- Ribot, JC, 2007. Representation, citizenship and the public domain in democratic decentralization. Development 50(1), 43–9. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.development.1100335

- Schapera, I with Comaroff, JL, 1953. The Tswana. Rev. edn. International African Institute, London.

- Segoagoe sa Bafokeng, 2006. Think Out of the Box and Dream Big, says Kgosi. Phokeng, South Africa.

- Sikakhane, J, 2009. Lessons in Democracy for ANC from Bafokeng. http://www.businessday.co.za/articles/Content.aspx?id=85694 Accessed 10 November 2009.

- Switzer, J, 2001. Armed conflict and natural resources. The case of the minerals sector. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Sector, Report No. 12, Minerals, Mining, and Sustainable Development, International Institute for Environment and Development, July. http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/G00940.pdf Accessed 15 March 2009.

- Zongwe, DP, 2008. The legal justifications for a people-based approach to the control of mineral resources in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Cornell Law School Inter-University Graduate Student Conference Papers, Paper 12. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1040&context=lps_clacp Accessed 14 May 2011.