Abstract

Existing empirical research on consumption patterns of the South African black middle class leans either on the theory of conspicuous consumption or culture-specific utility functions. This paper departs from treatment of the black middle class as a homogeneous group. By differentiating between a securely established group, with characteristics and consumption patterns similar to the white middle class, and an emerging group, often with weaker productive characteristics, the paper formally introduces economic vulnerability as a driver of consumption patterns. Households new to the middle class or uncertain of continued class membership are viewed as vulnerable. Consumption patterns of the emerging black middle class are observed to diverge substantially from the other groups, in terms of greater signalling of social status via visible consumption and preoccupation with reducing an historical asset deficit. We expect many of its members to join the established classes over time, converging to a new ‘middle class mean’.

1. Introduction

Much has been said about the levels of income inequality in South Africa, which do indeed remain amongst the worst in the world. Thabo Mbeki, soon thereafter president, described it eloquently back in 1993 when he first referred to South Africa as a country of two nations: one wealthy and historically white; and the other completely excluded from the economic mainstream, impoverished and black (Mbeki, Citation1998). After 20 years of democracy a large proportion of South African remains excluded from the labour market and the mainstream economy. South Africa's unemployment rate and Gini coefficient have remained stubbornly high. Increases in the frequency and violence of protest marches calling for improved service delivery and better economic conditions may be evidence that frustrations amongst the marginalised are escalating (Alexander, Citation2010; Office of the President, Citation2013).

The enduring problems with unemployment and the poor quality of service delivery sometimes mask the post-apartheid successes. This period has also seen a considerable expansion in service delivery coverage and a rapid increase in black affluence. In an article in this issue, Visagie shows that an additional 3.1 million black people were added to the middle class between 1993 and 2008 (see also Mamabolo, Citation2013). This shift is significant not only for markets and for economic growth, but in a broader societal context can be interpreted as an indication that South African society has become more open and dynamic. Furthermore, a growing middle class is considered socially beneficial by Easterly (Citation2001) and others due to its association with desirable outcomes such as more prudent policy, more education and improved political stability and democracy.

This paper attempts to contribute to a better understanding of the position and the impact of the rising black middle class on the South African economy by investigating the consumption preferences and choices of this growing consumer group. What requires explanation is why consumer patterns of the black middle class differ from those of their white peers. Following Bourdieu's (Citation1984) view that dominant tastes are a reflection of social power of different classes as reflected in their cultural capital, one would expect a convergence in the patterns of consumption of individuals entering the middle class to that of the dominant white middle class.

Much of the initial research on the purchasing decisions of the black middle class group was conducted by consumer market researchers eager to define and describe such spending habits in terms of new consumer categories and emphasising differences in underlying utility functions (‘tastes') between race groups that they often appear to regard as immutable. However, the consumer market focus on preferences and tastes has been criticised for perpetuating narrow stereotypes of the black middle class as conspicuous consumers with a taste for expensive cars, designer labels and large houses and a reputation as poor creditors. There have been only a handful of studies looking for more fundamental explanations for differences in spending patterns of the emergent black middle class in South Africa, notably Nieftagodien & Van der Berg (Citation2007) and Kaus (Citation2013).

The aim of this paper is to provide more encompassing hypotheses for why more vulnerable members of the middle class may exhibit different spending priorities. Significantly, these rival explanations find the rationale for the differential spending patterns of the emergent middle class in their vulnerable circumstances and their asset deficit, rather than in their unique intrinsic preferences. Such a conceptual shift may be subtle, but has important implications for anticipated trends. If differential spending patterns are attributable to intrinsic differences, then such gaps will remain, whereas if they are due to the vulnerable new entrant position of the emergent black middle class, then such gaps will fade and dissipate over time.

A first applicable theory relates to conspicuous consumption, as put forward by Veblen late in the nineteenth century. Under this theory, individuals derive utility from the social status linked to visible consumption of certain goods. Conspicuous consumption is thus consumption that is intended to be visible. This is in effect signalling wealth, which is generally unobserved. It is relative in the sense that an individual's status is socially contingent; that is, relative to that of other individuals within the reference group. In South Africa, race can be used to define the reference group, since race has played a significant role in forming cultural and economic identities. Kaus (Citation2013) finds variance in conspicuous consumption amongst groups, specifically 35 to 50% greater expenditure on visible consumption amongst coloured and black households relative to whites, linking this to a signalling model of social status.

A second applicable theory is that expenditure patterns within less affluent groups are driven by historical asset deficits. Black, coloured and Indian households are playing ‘catch up’ with the household asset levels typical of more established white middle class households.

This paper builds on previous studies demonstrating an economic perspective to show that expenditure patterns are primarily driven by rational and dynamic socio-economic factors and that one need not resort to explaining differences in underlying utility functions (tastes) or any other deterministic racial grouping attributes. These include status seeking in a broader sense as well as reducing the asset deficit. Together, these factors explain a significant portion of the observed variation in consumption expenditure across black and white members of the middle class.

Following a literature review, definitional issues are discussed and the methodology applied in this paper is presented. Results of descriptive analysis and modelling on the Income and Expenditure Survey 2010/11 (IES) suggest that greater conspicuous consumption observed amongst the black group reduces when taking into account new membership or uncertainty regarding future membership of the middle class. As the emerging black middle class establishes itself and members continue to transition into the established group, it is likely that substantial convergence to a new South African ‘middle class mean’ will take place.

2. Understanding the term ‘conspicuous consumption’

Much of the initial work on the emergent black middle class viewed this group primarily as an attractive consumer market, depicting its members as highly ambitious and aspirational in their spending patterns. The foundations for this belief are found in the group's investment in education, its robust expenditure underpinned by the recent growth in credit extension, and rising incomes associated with black economic empowerment policy, upward social mobility and economic growth. Krige (Citation2009, Citation2011) notes that commentators and researchers have criticised the work on so-called ‘Black Diamonds' as propagating cultural stereotypes. Members of the black middle class argue that the black middle class is incorrectly painted as greedy and consumerist, resulting in what is seen as a simplistic, patronising and inaccurate representation of reality. Such a stylised caricature of black middle-class consumers suggests instead that membership of a specific subgroup is the most important explanation for observed consumer patterns, obscuring the role of rational economic drivers of consumption expenditure.

Veblen's economic theory of conspicuous consumption proposes that individuals gain social status by signalling their wealth to their reference group by engaging in conspicuous leisure or conspicuous consumption, the latter defined as visible consumption of certain goods that are associated with social status (Trigg, Citation2001; Kaus, Citation2013). Veblen (Citation1899) argued that individuals demonstrate their wealth and so gain in social status by showing that they can afford to waste time, effort and money. Veblen, however, also noted that amongst the more established members of the upper class the need to signal wealth may be diminished, partly because they can signal their wealth through a set of distinct habits and tastes which they acquired tacitly through their social upbringing.

This insight is central to the more recent work of Bourdieu (Citation1984) on how tastes and preferences can signal and entrench class. He argues that taste and preferences are class markers that distinguish and legitimise privilege. Each class therefore aspires to mimic the tastes and consumption patterns of those above it. According to such a perspective, the established upper classes would be less likely to exhibit conspicuous consumption while it would be important for the middle class to distinguish themselves from the working class (Trigg, Citation2001).

Bourdieu (Citation1984) believes that displays of consumption need not be crude and deliberate, but can often work through a tacit code acquired through socialisation and motivated by socialised norms and tendencies that guide behaviour and thought (Lamont & Lareau, Citation1988). Linked to this theory is the notion of cultural capital, which provides an avenue through which groups can express domination within the social hierarchy through the claim of possessing ‘good taste’. Bourdieu's (Citation1984) conceptualisation of the complex social constellation that implicitly governs and guides the choices of the members of social groups allows for a more intricate, but also more fluid, view of class structure and expenditure patterns.

3. Previous empirical investigations of the relationship between consumption and class

The work of Veblen and more recently Bourdieu has inspired a large body of empirical research examining the relationship between conspicuous consumption and class. Charles et al. (Citation2009) and Kaus (Citation2013) postulate that conspicuous consumption is socially contingent in the sense that an individual's visible expenditure is influenced by the characteristics of the reference group and his/her position within the income distribution of this reference group.

These authors examine whether conspicuous consumption will increase as the mean income of the reference group decreases. The intuition is that an individual from a relatively poor reference group who aspires to achieve social status of higher groups will have an incentive to engage in additional signalling, given the general perception of low status associated with this group.

They also investigate whether conspicuous consumption will increase as income inequality within the reference group increases. The intuition here is that additional signalling may be required to demonstrate positioning near the top of the reference group income distribution. Lastly, they explore whether conspicuous consumption increases with the permanent income of the relevant household.

Charles et al. (Citation2009) search for inter-racial evidence of conspicuous consumption in US data, using nationally representative household surveys and panels. Defining conspicuous consumption as expenditure on items such as cars, clothing and jewellery, they find that black and Hispanic individuals devote substantially larger shares to such conspicuous consumption, consistent with a model of status seeking. The trade-off associated with higher visible consumption is lower consumption of all other categories of current consumption – notably education and health – as well as future consumption. This implies a significant and intertemporal cost to conspicuous consumption in terms of other consumption foregone.

The authors examine whether this conspicuous consumption is associated with membership of particular reference (race and regional) groups. They find that visible consumption increases with income and the dispersion (inequality) of reference group income, while it decreases with reference group income (Charles et al., Citation2009). Since a socially contingent model of conspicuous consumption explains much of the observed variation in conspicuous consumption, the authors therefore do not give much weight to deterministic factors such as racial differences in tastes.

Kaus (Citation2013) follows a similar methodology but focuses instead on South Africa using the Income and Expenditure Surveys of 1995, 2000 and 2005. He finds that coloured and black households spend 35 to 50% more on visible goods than do comparable white households.Footnote5 When exploring the status-seeking model as an explanation for this consumption, Kaus also finds that visible consumption is higher when reference group income is lower. However, the results are not replicated within all race groups, and he therefore does not rule out that there are differences in underlying tastes and preferences. Trade-offs occur through lower spending on health, housing, entertainment and communications amongst black and coloured households.

Whilst these studies link conspicuous consumptions to specific income characteristics of social groups, they do not take into account the potential impacts of small movements across a class threshold on expenditure patterns. Since income-based approaches to the middle class assume enjoyment of an aspirational lifestyle associated with incomes above a certain threshold, proximity to this point should be an important driver of expenditure patterns within the middle class. An innovative new study by Lopez-Calva & Ortiz-Juarez (Citation2011) examines vulnerability to poverty in the context of a rising middle class in Central and Latin America, observing that a group of households located between the middle class and the poor in the income distribution remains vulnerable to falling back into poverty. This may be explained in terms of structural characteristics of these households. Applying the Weberian view of class, these individuals are grouped into classes according to common economic ‘life chances' that influence their market income opportunities. The middle class is defined as a group benefiting from a broad skills base and substantial investment in education, offering it a significant chance of attaining economic prosperity over time.

The income-based approach to definitions of the middle class necessarily segments the population independently of productive characteristics such as educational attainment. Accordingly, there may be ‘subgroups' within the affluence-based middle-class group that exhibit fundamentally different characteristics associated with social mobility, thus enjoying very different ‘life chances'. In a similar vein, Goldthorpe & McKnight (Citation2004) distinguish between groups of workers on the basis of economic security, stability and prospects (Lopez-Calva & Ortiz-Juarez Citation2011). This echoes Ravallion's (Citation2010) work, which points out that the growing middle class in developing countries remains vulnerable, despite its newly acquired relative affluence. This vulnerability itself may be an important driver of expenditure patterns, should a household feel insecure due to recently joining the middle class or lacking sufficient productive resources to be confident of sustaining class membership.

A separate explanation for differing racially based expenditure patterns is advanced by Nieftagodien & Van der Berg (Citation2007), framing the issue in terms of an ‘asset deficit’. They argue that the ramifications of past economic racial segregation could explain currently observed differences in asset levels, with black and coloured households consequently at a disadvantage in terms of ownership of household assets. In white households, there is likely to be some intergenerational transfer of these goods, enabling new generations to allocate a greater share of their disposable income to other items. Their research shows that black middle-class households have asset deficits and are more likely than their white counterparts to purchase assets.

4. Data

This paper mainly uses the IES for analysis. This survey was conducted by Statistics South Africa during the period of September 2010 to August 2011. Data were recorded for a sample of 25 328 households across the country over a 12-month period. The IES is mainly conducted to provide statistical information on household consumption expenditure patterns for the calculation of the weights for the consumer price index. A combination of diary and recall methods was used to sample these households. Each household was presented with a questionnaire and a two-week diary. The diary acquisition approach may generate underlying measurement error due to the fact that respondents may become fatigued or forget to complete their diaries on a daily basis – thus they may not comprehensively record all actual expenditures over the two-week period (Visagie & Posel, Citation2013).

Although the primary aim of the IES is to provide information for the readjustment of the consumer price index basket of goods and services, a secondary aim is to provide additional information on socio-economic conditions. In this paper, additional information on the presence of assets is also used to create two indices to rank middle-class households in the context of socio-economic conditions.

5. Analysis of conspicuous consumption in the South African middle class

5.1 Defining the middle class

The analysis uses an income-based definition of the middle class to examine what consumption patterns reveal about the evolving social landscape and de-racialisation in post-apartheid South Africa. It investigates the distinct consumption patterns of households enjoying at least middle-class lifestyles, namely those that have enough income that they no longer need struggle with the necessities and the basics, but have sufficient income to make allocations towards discretionary expenditure. We consequently employ an income-based approach in applying this definition. Only a lower income cut-off value is applied, set at a level that yields a middle class comprising the most affluent 15% of the population, namely R53 217 per capita per annum in 2010/11 terms.

An upper income cut-off value is not applied, because such an incision leaves only a slither of very rich at the top. Additionally, because of the small number of observations in what would be the upper-income group within the black population, it is difficult to meaningfully analyse such a category over time or to decompose it by other attributes and qualities. While the distinction between the middle and upper classes may be of interest for understanding capital formation or the distributional effects of growth, the wealth of the upper classes cannot be captured and represented reliably and accurately without specialised wealth surveys.

5.2 Distinguishing the emergent and the established middle class

Based on asset levels, we then distinguish between two subgroups of the middle class, namely the emerging and established middle class. The purpose of this distinction is to allow for a more nuanced, dynamic analysis of spending patterns that implicitly takes into account the duration and degree of class inclusion. In describing the black middle class in 2005, Schlemmer (Citation2005:5) refers to lagging security with respect to asset ownership, status and self-confidence within the group, still very new and small then.Footnote6 It is a hypothesis of the current analysis that such insecurity remains a characteristic feature of the emerging component of the black middle class, associated with households that have recently joined the middle class or whose grasp on middle-class status is tenuous, for example, due to unstable forms of income. This builds on the approach taken by Schlemmer, which refers to a ‘core middle class' comprising households containing highly skilled workers such as professionals and managers, as distinct from a ‘lower middle class' made up of more modestly salaried clerical workers, teachers, nurses, and so on. Specifically he observed a notable lack of unity in class identity in this group with many individuals failing to identify themselves as belonging in the middle class.

The work by Nieftagodien & Van der Berg (Citation2007) suggests that a high expenditure priority for new members to the middle class is the acquisition of assets typically associated with middle-class lifestyles, such as white goods and cars. By this rationale, established households that have a longer membership of the middle class have accumulated many of the goods traditionally found in white middle-class households, and should thus score higher on the asset index. Conversely, new entrants to the middle class will face an asset deficit.

To provide further evidence of the asset deficit amongst new entrants to the middle class, we turn to data from the 2012A version of the All Media and Products Survey on ownership and purchases of large household appliances. This survey shows that white households with a monthly income of at least R8 000 are six times more likely than their equally affluent black counterparts to own a tumble dryer, whereas the latter are five times more likely to have recently acquired one. Similarly, black households in this income category are only one-half as likely as white households to own a washing machine, yet responses regarding purchasing patterns indicate that they appear four times more likely to have recently bought a washing machine. There is also evidence that they are significantly more likely to purchase microwaves and refrigerators. This provides some evidence that relatively affluent black households experience an asset deficit compared with whites of similar income, but they are allocating more of their resources to eliminating this deficit.

To create a single indicator variable to collectively represent the assets of a household, we create an index from binary variables reflecting ownership of white goods and other household assets. These include televisions,Footnote7 DVD players, refrigerators, stoves, microwaves, washing machines, motor vehicles, computers, cameras, telephones, satellite dishes, the Internet, furniture and ownership of a brick house. Of the three most common methods used to construct an asset index – namely factor analysis, principal component analysis and multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) – MCA is selected because it imposes fewer restrictions on the survey matrix (it does not, for instance, assume a normal distribution of the underlying variables) and because it is suited to the use of categorical variables (Booysen et al., Citation2008). Using MCA as a data reduction technique, an asset index is constructed and black households within the middle class as defined here are then divided on the basis of this index into those with more assets (constituting a more established grouping within the middle class) and those with fewer assets, referred to as an emerging middle class.

5.3 Defining conspicuous consumption

Our analysis defines conspicuous consumption as expenditure on categories of goods and services that may be considered luxury items associated with affluent lifestyles. By its very nature, conspicuous consumption will be defined to include different items according to the consumer's social context since it is a socially contingent concept. In our paper focusing on South African consumers, both Veblen's theoretical framework for conspicuous consumption and the practical constraints arising from survey data quality and accuracy informed its measure. Conspicuous consumption was accordingly defined to include expenditure associated with clothing, footwear, restaurants, grooming products and services, watches, handbags, televisions and satellite dishes.Footnote8 However, when interpreting this it is important to bear in mind that even the poorest households will allocate some money towards footwear, clothing and grooming. Only that part of expenditure on these items which exceeds functional levels can properly be regarded as an attempt to signal wealth. Therefore, this variable should be interpreted in a relative sense. Some of what is interpreted as conspicuous consumption could be necessary and functional investment in household assets and other goods.

5.4 Descriptive analysis

Firstly, a descriptive analysis is presented in , reflecting some interesting contrasts between the subgroups comprising the middle class.

Table 1: Descriptive characteristics of the middle class

As anticipated, black established and white middle-class groups look quite similar in terms of productive characteristics. Approximately one-half of households in these groups have at least a diploma, while more than 20% have a degree. Similarly, household heads are older and probably well established in their careers, reflected in high scores on the asset index. The most obvious difference is the much higher per-capita income level of white household heads, perhaps due to a combination of more experience (household heads are older), greater historical representation in financially rewarding occupations, more profitable social networks (greater social capital, in Bourdieu's terms) and more reliance on passive income streams. This last factor is borne out by the much lower employment rates of white household heads, which is not fully explained by slightly higher self-employment rates.

By contrast, emerging black middle-class households display substantially less entrenched prosperity. Household heads are younger and thus less experienced, and are much less likely to have tertiary education than their peers, suggesting lower human capital overall. Furthermore, emerging black households are more likely to be female-headed, single-person households, and to be located in rural areas. In the South African context, all of these characteristics are typically associated with lower incomes and greater vulnerability. It is thus unsurprising that scores on the asset index are much lower, in line with relatively low per-capita incomes.

It seems quite likely that a portion of the black emerging group – typically with young, well-educated household heads and located in urban areas – will transition into the black established group over time, as they gain experience in the workplace and are promoted into more lucrative positions. However, a significant portion of this group is structurally less advantaged and will thus remain marginal members of the middle-class group, their social mobility potential capped by lack of access to opportunities in urban labour markets, or by not having an income-earning spouse, for example.

Interestingly, and in line with the hypothesis, the black emerging group allocates more expenditure towards both conspicuous consumption items and assets than either of the other subgroups.

5.5 Regression analysis

We perform regression analysis to determine whether expenditure patterns are significantly different between groups once control variables are added. The analysis applies an augmented version of the permanent income hypothesis to model spending patterns. Formally, we model conspicuous consumption expenditure share as:

where r is a range of racial dummy variables, p represents the household's permanent income (instrumented here by per-capita household income), ‘a’ represents the score on the asset index, and Xi is a vector of controls.

Dummy variables indicate whether the head of a household is black, Indian or coloured (the reference group is white household heads). Other standard controls that may proxy for differences in prices, tastes and preferences include a dummy variable for rural location, the number of children in the household, the number of elderly people in the household and a dummy indicating whether the head of the household is female. Per-capita household expenditure is included as an indicator of the household's spending power (for developing countries, expenditure is regarded as a more reliable and accurate measure of well-being that can also proxy for income).

In line with the theories of Modigliani & Brumberg (Citation1954) and Milton Friedman (Citation1957), income smoothing could play an important role in consumption patterns. The age and the years of education of the household head influence their earning capacity; that is, they act as further proxies for permanent income (Charles et al., Citation2009:432). Intuitively, one would expect that a household with a higher expectation of future earnings may consume more than other households currently earning the same income.

Modelling the share of expenditure devoted to conspicuous consumption as the dependent variable should control for existing levels of asset ownership, which are expected to vary between groups. According to the asset deficit hypothesis, the observed racial differences in consumption expenditure patterns between groups are expected to decrease substantially over time because they are dictated by asset accumulation patterns – over lifecycles, but also across generations. Most members of the black middle class are young and in many cases they are the first generation of their families to belong to the middle class. Compared with both their older counterparts and those born into middle-class families (e.g. many white members of the middle class), these younger middle-class households start their careers with a deficit of assets. Within their financial constraints, such households can only eliminate their asset deficit gradually and over an extended period.

presents the factors associated with a higher conspicuous consumption share for middle-class South Africans. Because of the correlation between household expenditure per capita and the educational attainment of the head of the household, four sets of results are presented, with educational attainment and the asset index being excluded in some regressions. Each regression shows a basic model of spending, including proxies for spending power (i.e. expenditure per capita and its square) and a range of demographic characteristics that can drive consumption priorities and preferences (i.e. race and household structure). A dummy for a rural location is included because rural inhabitants often face different prices and choice sets than urban inhabitants. Charles et al. (Citation2009) and Kaus (Citation2013) define reference groups as a composite of race group and region; since sufficiently comprehensive district level data do not exist in the IES, the regressions simply control for the urban/rural distinction. We include both the log of per-capita expenditure and the square of log per-capita expenditure because the relationship between logged household per-capita expenditure and conspicuous consumption as a share of expenditure is an inverted U, rising steeply at low levels of expenditure and then flattening out and eventually declining at higher levels of expenditure.

Table 2: Regression analysis of conspicuous consumption

All of the coefficients have the expected signs. Expenditure per capita and expenditure per capita square both have negative coefficients, showing that for the South African middle class the share of expenditure allocated to conspicuous consumption decreases with an increase in expenditure per capita. As reported earlier, this negative relationship only holds at the top end of the expenditure distribution and there is a positive relationship between conspicuous consumption share and expenditure at lower levels of expenditure. This is consistent with a view in which the upper classes, proxied here by households with high expenditure, do not experience the same need to signal their wealth as the middle classes.

Age has a negative coefficient, showing that younger members of the middle class tend to allocate a greater share of expenditure towards conspicuous consumption. Given that separate proxies for expenditure, education and assets have been included, the negative coefficient on age may be interpreted as a possible indication that younger members of the middle class may still feel more vulnerable, perhaps because they have fewer years of experience in the labour market. This may lead to them being more easily elicited to signal their wealth through their consumption behaviour. They are also more likely to have recently arrived in the prosperous group, particularly if they are not white.

Rural inhabitants tend to have a lower conspicuous consumption share, which could perhaps be attributable to lower social pressure in rural areas; that is, the reference group may differ.

As would be expected, households with more dependents (children and elders) are less prone to conspicuous consumption. Put differently, where a greater share of the household consists of adults of working age, a higher conspicuous consumption share would be expected. This would also be associated with higher disposable income in households with more productive capacity.

The coefficient on female-headed households is positive, but not significant. A positive association was expected due to such households representing a highly vulnerable segment of the population.

The white middle class is the reference group for the regression. Accordingly, a positive coefficient on the racial indicator variable shows that members of the relevant racial group tend to devote a higher proportion of expenditure to conspicuous consumption than the white middle class. The work of Charles et al. (Citation2009) and Kaus (Citation2013) would predict that the urge to signal wealth would be stronger amongst coloured and black South Africans, who experience higher intra-group inequality and lower mean income. Consequently, prosperous members of these groups would be more inclined to use visual cues to set themselves apart from the rest of their reference groups. These results confirm this and show that, all other things equal, coloured and black households spend a significantly larger share of their money on items that can visibly signal wealth.

Note, however, that the coefficient on the black emerging middle class indicator variable is almost double that of the coefficient on the black established middle class. This suggests that a large part of observed black conspicuous consumption is driven by the emerging middle-class group, which appears to have a greater signalling need even after controlling for income levels. This may be associated with recent arrival in or due to uncertain continued membership of this status class, due, for instance, to relatively low educational attainment.

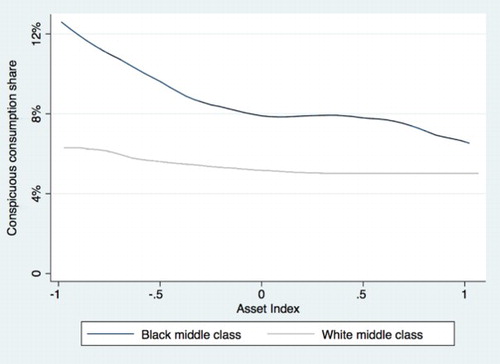

In line with the asset deficit hypothesis, the asset index is significant and negative and reduces the coefficient on the black emergent indicator variable. Interestingly, shows that the black middle class' conspicuous consumption shares converge towards white middle-class levels as their asset levels increase. The wide divergence in conspicuous expenditure at low levels of assets may suggest that, for first-generation middle-class members, the asset accumulation process runs parallel to and proxies for equally important socio-economic orientation and consolidation processes. These may include the expansion and deepening of social networks, gaining more labour market experience and tacit knowledge about social conventions and systems. Such anchoring and rooting processes would enhance feelings of security and belonging and objectively reduce vulnerability through building social capital, which would then reduce the need to signal wealth via conspicuous consumption.

Figure 1: Conspicuous consumption shares of black and white middle-class households by asset index

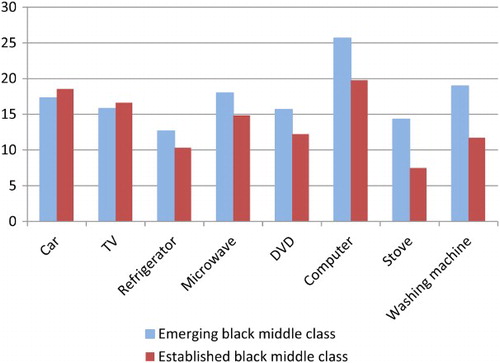

Whilst black middle-class households spend more on conspicuous consumption as a share of total expenditure, it is equally true that their spending patterns reflect that they are still catching up on household asset stocks. This is particularly true for the emerging group amongst black middle-class households. In other words, there does not appear to be a significant trade-off for these households between conspicuous consumption expenditure and filling the asset deficit. To augment regression analysis, shows that middle-class households with lower stores of assets (i.e. emerging middle class) were more likely to report recent asset purchases (over the previous 12 months) than their established counterparts. The only exceptions are cars and televisions. Regarding assets such as these where major innovations occur frequently, consumers may replace goods earlier than strictly required in order to signal social status or to access productivity gains or luxury features associated with the additional functionality of the new version. For most assets, however, the emerging black middle class is considerably more likely to have reported recent purchases. The strikingly high incidence of computer purchases amongst the emerging black middle-class group is particularly interesting because it may speak more directly to the socialisation associated with recently joining the middle class, referenced earlier.

6. Conclusions

The results of the empirical research reported here are consistent with the hypotheses set out earlier. Conspicuous consumption does appear to be socially contingent, where the reference group is defined as a particular race group. Such conspicuous consumption increases in groups where mean incomes are lower and inequality higher, as was predicted and also found in earlier studies in both South Africa and the USA. Also, in line with hypotheses, a large proportion of the observed high conspicuous consumption levels within the black middle-class group can be explained by new or perhaps insecure membership of the group. Finally, the empirical evidence shows that conspicuous consumption is negatively related to asset ownership. Thus, as asset ownership rises, it is likely that conspicuous consumption decreases – perhaps because the need to signal economic status declines commensurately.

The available evidence thus supports an explanation for the pattern of spending amongst black middle-class consumers being different from that of their white counterparts due to two factors: their vulnerability as new entrants to the middle class, and their associated asset deficit. Conspicuous consumption is natural amongst those who are economically more successful than the mean within their reference group, particularly when this group is not prosperous on average. It is likely to be a more prominent feature of consumption whilst this higher economic status is still new, and also where such status is still tenuous because of real or perceived income vulnerability.

If the hypotheses set out here hold, one would expect the more established part of the black middle class to grow over time and to exhibit consumer patterns that would increasingly resemble those of other established members of the middle class. If economic trends continue fuelling growth of the black middle class, social mobility will propel more individuals into the middle class, refilling the ranks of the emergent middle class. Conspicuous consumption will thus be an enduring feature of South African consumer expenditure patterns.

Given that both this work and that of Kaus (Citation2013) are reliant on the IES data, it will be useful to test the robustness of these findings with analysis from other data sources such as the All Media and Products Surveys.

Notes

5However, note that this effect is not observed for cars in the South African context (Kaus, Citation2013:20).

6Almost one-third of black middle-class survey respondents identified themselves as ‘working class' (Schlemmer, Citation2005).

7We conducted sensitivity testing due to concerns about the inclusion of expenditure on television in the conspicuous consumption share and television ownership in the asset index, but excluding television from the asset index does not influence the results presented here in any meaningful way.

8One may argue that purchasing a car is a necessity in a country such as South Africa, which historically has offered individuals limited options for reliable and convenient public transport, particularly within urban areas. Therefore, only excessive expenditure on (luxury) cars can be regarded as conspicuous consumption. Given limited information on the nature and value of car purchases in the data and the fact that the large value of car purchases would result in it dominating conspicuous consumption spending patterns, car spending was not included in our analysis. This deviates from the work of Charles et al. (Citation2009) and Kaus (Citation2013), who included expenditure on cars as conspicuous consumption in the American and South African contexts respectively.

References

- Alexander, P, 2010. Rebellion of the poor: South Africa's service delivery protests – A preliminary analysis. Review of African Political Economy 37(123), 25–40. doi: 10.1080/03056241003637870

- Bourdieu, P, 1984. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Routledge, London.

- Booysen, F, van der Berg, S, Burger, R, von Maltitz, M & Du Rand, G, 2008. Using an asset index to assess trends in poverty in seven sub-saharan african countries. World Development 36(6), 1113–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.10.008

- Charles, KK, Hurst, E & Roussanov, N, 2009. Conspicuous consumption and race. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(2), 425–67. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.425

- Easterly, W, 2001. The middle class consensus and economic development. Journal of Economic Growth 6, 317–35. doi: 10.1023/A:1012786330095

- Friedman, M, 1957. A Theory of the Consumption Function. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Goldthorpe, JH & McKnight, A, 2004. The economic basis of social class. CASE paper, 80. Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics and Political Science, London.

- Kaus, W. 2013. Conspicuous consumption and ‘race’: Evidence from South Africa. Journal of Development Economics 100(1), 63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.07.004

- Krige, D, 2011. Debating the black diamond label for South Africa's black middle class. Paper presented at the annual Anthropology Southern African Conference, 3–5 September, Stellenbosch University.

- Lamont, M & Lareau, A, 1988. Cultural capital: Allusions, gaps, and glissandos in recent theoretical developments. Sociological Theory 6, 153–68. doi: 10.2307/202113

- Lopez-Calva, LF & Ortiz-Juarez, E, 2011. A vulnerability approach to the definition of the middle class. Policy Research Working Paper Series 5902. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Mamabolo, K, 2013. 4 Million and Rising – The South African Black Middle Class. www.fbreporter.com Accessed 5 November 2013.

- Mbeki, T, 1998. Statement of Deputy President Thabo Mbeki at the Opening of the Debate in the National Assembly on ‘Reconciliation and Nation Building’, 29 May, National Assembly, Cape Town.

- Modigliani, F & Brumberg, R, 1954. Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In Kurihara, KK (Ed.), Post-Keynesian Economics. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

- Nieftagodien, S & Van der Berg, S, 2007. Consumption patterns and the black middle class: The role of assets. Working Paper 02/2007, Stellenbosch University, Department of Economics

- Office of the President, 2013. Development Indicators 2012. The Presidency, Pretoria. http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/MediaLib/Downloads/Home/Publications/DPMEIndicators2013/DPME%20Indicators%202013.pdf Accessed 8 November 2014.

- Ravallion, M, 2010. The developing world's bulging (but vulnerable) middle class. World Development 38(4), 445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.007

- Schlemmer, L, 2005. Lost in transformation? South Africa's emerging African middle class. CDE Focus No 8, August, Centre for Development and Enterprise, Johannesburg.

- Trigg, AB, 2001. Veblen, Bourdieu and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Economic Issues 3(1), 99–115.

- Veblen, T, 1899. The theory of the leisure class. In the collected works of Thorstein Veblen Vol. 1. Reprint. Routledge: London.

- Visagie, J & Posel, D, 2013. A reconsideration of what and who is middle class in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 30(2), 149–67. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.797224