Abstract

Cultural tourism programmes (CTPs) provide opportunities for rural communities to supplement their income. While these programmes are intended to empower local people and reduce poverty, the mechanisms used for choosing the targeted ‘communities' remain largely unexamined. This paper analyses the planning, structure and implementation of CTPs as a form of community-based tourism in selected areas in Tanzania. Data were collected from two CTP groups (10 people in total) and five government officials at the national level using in-depth interviews. Analysis was carried out using NVIVO for theme generation. Major themes derived include lack of clear description of who constitutes CTPs and that existing CTPs differ greatly in terms of structure, size, development level and resource capacity, and many lack clear benefit-sharing mechanisms. There is a need for the government to continue supporting these initiatives at all levels, to nurture newly created CTPs and to provide continual technical support for the existing ones.

1. Introduction

A sense of community ownership, a feeling of responsibility and practical involvement in tourism has been heralded by researchers and practitioners as central to the sustainability of tourism and of great importance to planners, managers and operators (Page & Dowling, Citation2002; Boyd & Singh, Citation2003; UNWTO, Citation2004). Although the term community has its roots in social science, it is recognised as being highly vague, with numerous competing interpretations and connotations (Selznick, Citation1996; McLain & Jones, Citation1997). The term ‘community’ is used either implicitly or explicitly in many tourism initiatives such as pro-poor tourism, responsible tourism, sustainable tourism, ecotourism and community-based tourism (CBT). Many of these tourism initiatives indicate that there is a strong link between tourism and local communities in which tourism takes place. However, most of these initiatives do not clearly define what a community is and who is considered to be a legitimate community member. This fluffiness has led to many conflicts and inefficiency in operating CBT initiatives (Nelson, Citation2007). The need to clearly define what is a community and its scope in a local setting is therefore a key for the implementation and success of any tourism enterprise at the local level. Tosun (Citation2000) contends that one of the reasons why CBT programmes are hindered in their success in many areas is because of the assumptions embedded within the community concept itself. Similarly, when you look at many government documents, the involvement of communities, particularly local communities, is considered to be central in achieving development goals (e.g. URT, Citation1999, Citation2002; MNRT, Citation2007). Many of these documents show that rural communities need to have a stake in their own development and that it is their constitutional right to have a direct say in matters affecting their future (Kepe, Citation1999). However, it is unfortunate that even these important government documents do not clearly delineate what community really is.

World Wildlife Fund (WWF) defines CBT as a form of tourism ‘where the local community has substantial control over, and involvement in, its development and management, and a major proportion of the benefits remain within the community’ (WWF, Citation2001:2). Thus, CBT promotes community participation and seeks to deliver wider community benefits. Recognition of the need for community participation in managing natural and cultural resources makes community participation in CBT an increasingly important aspect of its sustainability (cf. Hibbard & Lurie, Citation2000; Mitchell & Reid, Citation2001). Rozemeijer's (Citation2001) definition of CBT also suggests that community participation and ownership are key issues in CBT. While CBT programmes are intended to empower people and reduce the poverty level in rural communities (Rozemeijer, Citation2001), the nature of community representation in such ventures has remained largely unexamined (Salazar, Citation2012).

The current article does not attempt to offer a definition of what a community is or what a community is not; rather, its intention is to use the term community as a lens to understand the planning and structure of CBT using cultural tourism programmes (CTPs) in Tanzania. Specifically, the term community is used as a means to understand what and who constitute the CTPs. This is because the fuzziness around the definition tends to pave ways for exploitative relationships in many areas where CBT programmes are practiced and makes the sustainability of these initiatives highly contentious. Lukkarinen (Citation2005) and Simpson (Citation2008:3) posit that destination communities must mutually benefit if tourism is to be viable and sustainable in the long term. Similarly, according to Pearce (Citation1992), CBT presents a way to provide an equitable flow of benefits to all members affected by tourism through consensus-based decision-making and local control of development. However, the main challenge in CBT still lies in how the community is defined and represented (Belsky, Citation1999; Blackstock, Citation2005; Snyder & Sulle, Citation2011).

Drawing on the fieldwork conducted during summer 2012 in selected CTP initiatives in Tanzania, this paper uses a qualitative approach to explore a number of queries pertinent to CTP in Tanzania such as: how do CTP initiatives fit within the current tourism system in Tanzania? Who are the stakeholders in these CTPs and how are they involved? What are the forms of benefit-sharing mechanisms? What are the structure and forms of community participation? Two CTPs, Chilunga and Matunda, were purposively selected for the study based on their geographical location in relation to the prime tourist zones in the country. Chilunga is located on the eastern tourism circuit while Matunda is located along the prime tourist zone, the northern tourist circuit. A brief description of CTPs in the Tanzanian context will be made followed by the methods and results sections. The way forward that geared towards increasing community involvement, improving visitor experience and promoting equity in benefit sharing among these ventures will conclude the paper.

2. Community-based tourism in Tanzania: Definition and historical development

CBT in Tanzania has grown rapidly over the last two decades. Most CBTs in Tanzania fall under CTPs (UNWTO, Citation2003). This is because in most cases when tourists visit the rural areas where most of these tourism ventures are located they experience local people's everyday lives, their cultures and how they interact with nature. The term ‘cultural tourism’ is subject to many definitions and interpretations (Sofield & Birtles, Citation1996) and its usage is associated with much confusion (Hughes, Citation1996). Silberberg (Citation1995) describes cultural tourism as ‘visits by persons from outside the host community motivated wholly or in part by interest in the historical, artistic, scientific or lifestyle/heritage offerings of a community, region, group or institution’ (Silberberg, Citation1995:2).

In the Tanzanian context, however, cultural tourism adopts a CBT approach in which people are directly involved in designing, organising tours and showing tourists aspects of their lives (URT, Citation2010). This tourism niche is highly supported in tourism discourses. For instance in 2001, the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) concluded that probably the most promising niche to develop CBT programmes is through CTPs. In that year, CTPs were identified as one of the major growth markets in global tourism. The main strength of cultural tourism lies in its potential to empower rural communities and to make a substantial contribution to development and the eradication of rural poverty (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007). Similarly, Salazar (Citation2012) argues that CBT initiatives which are designed and implemented through community consensus, rather than centrally planned (top-down), experience less negative effects. Throughout this paper, CTP will be used instead of CBT to denote the form of CBT that is practiced in Tanzania.

The CTP in Tanzania as a tourism niche dates back to 1994 (Salazar, Citation2012). It started as a voluntary request from local Maasai Youth who wanted to develop tourism in their village. The idea to establish CBT around the village area was interesting because it emerged from the grass-roots level. A bottom-up approach is supported by many scholars as the most effective and appropriate means of community participation in decision-making regarding their development (see for example Pretty, Citation1995; Tosun, Citation1999, Citation2006; Simpson, Citation2008; Michael et al., Citation2013). Since SNV had profound expertise and experience in CBT from other countries such as Bolivia, Botswana, Cameroon, Laos, Nepal and Vietnam (Caalders & Cottrell, Citation2001; Rozemeijer, Citation2001), they were consulted for support and technical advice. In collaboration with the Tanzania Tourist Board (TTB), SNV provided technical support in terms of coordinated and organised trainings for tour guides for all CTPs (Salazar, Citation2012).

The TTB, on the other hand, was responsible for promoting CTPs to both local and international markets (De Jong & Liejzer, Citation1999). A year later, SNV launched the first CTP in the country. Salazar (Citation2012) shows that SNV was surprised to find out that when they were planning to expand its tourism activities to other areas in the country, many local communities had already shown interest which made it easy for them to facilitate its expansion. The prevailing environment as well as readiness of the local communities made it possible for SNV to initiate many CTP initiatives within a short period without many challenges. In 2001, five years after the establishment of 18 pilot CTPs, the number of tourists increased to 7000 from 2600 in 1998 (Salazar, Citation2012:14). During this time, Tanzania received around 500 000 tourists (UNWTO, Citation2003). After the five years, SNV support phased out. Following withdraw of SNV, many CTPs collapsed due to lack of finance and regular technical support. Similarly, those which continued to survive had many internal conflicts with regard to land ownership, resources management, inequitable benefit distribution among members and poor coordination (Nelson, Citation2004).

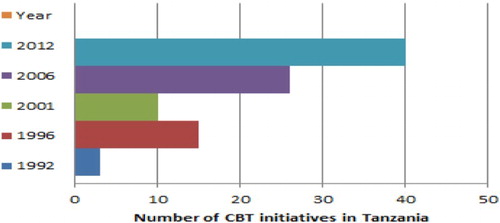

Owing to low technical support from the responsible agencies, many CTPs operated haphazardly and some even collapsed in the period 2001–06. The intended Tanzania Cultural Tourism Organization that was created with the purpose of managing various CTP modules also collapsed just after it was established. In 2006/07, the TTB and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism received technical and financial support from SNV and the UNWTO-STEP project and the process to institute guidelines for establishing and managing CTP activities revived. However, it was not until 2012 that these guidelines were officially approved. During fieldwork about 40 CTPs were identified (), most of them located in the northern tourist circuit (Kilimanjaro, Arusha and Manyara regions) ().

Figure 2: Map of Tanzania showing the location of CTPs

3. Methodology

The fieldwork was carried out between June and July 2012. In-depth interviews were used for data collection. The interview method was chosen to provide valuable insights and opinions of those involved in the operations of CTPs. Two CTPs, Chilunga and Matunda, were purposively selected for the study based on their geographical location in relation to the main tourist zones in the country. Chilunga is located on the eastern tourism circuit while Matunda is located along the prime tourist zone, the northern tourist circuit. The two CTPs were chosen not for comparison purposes but for providing a general understanding of the research questions stipulated in the Introduction.

Matunda Cultural Tourism and Safari Organisation is located in Arusha region. It is also known as Peace Matunda Tours, operating cultural tours in the spirit of eco-tourism with main activities being walking and mountain biking. Chilunga CTP is located in Morogoro Region, 95 km west of Dar es Salaam. It is situated in the eastern tourist circuit. The region where Chilunga is located is a beautiful region with the Uluguru Mountains natural forests and endemic bird species. Apart from these attractions, visitors can enjoy mountain hikes, historical sites, waterfalls, panoramic viewpoints and glimpses of the local culture.

Government officials at the national level were purposeful selected based on their knowledge and contribution to the establishment of the CTP in the country (two people), those who are currently responsible for overseeing the activities of the CTP (one country coordinator) as well as those responsible for marketing the CTPs (two people from the TTB).

A snowball sampling technique was used to identify interviewees to be included in the study. The total number of interviewees was 15. Ten people from the two CTPs (seven from Matunda and three from Chilunga) and five government officials were used to collect information for this research. The interview session was conducted in an informal setting to facilitate interviewee comfort during the process. All interviews were conducted in Swahili language and later translated into English. Each interview lasted for approximately 90 minutes. Interviews mainly focused on historical development of CTPs in Tanzania and their operation within the current tourism system, the stakeholders involved and their participation, benefit-sharing mechanisms and the forms of community participation.

Interview responses were recorded in a field-notes book by the researchers. Two researchers conducted research together; one was responsible for asking the questions and the second researcher only intervened when there was a need for a follow-up or clarification during the interview process. After completion of all interviews, the researchers cross-checked each other's recordings to ascertain the validity and reliability of the information collected. In addition, secondary data were also used to gain more information, or supplement or validate data collected in fieldwork during interviews.

NVIVO 10 was used for data analysis. The coding procedure as described by Patton (Citation2002) and Miles & Huberman (Citation1994) was adopted during analysis. Independent coding was done by both researchers and later a comparison was made to cross-check the inter-coder reliability and theme agreement. Data analysis involved two stages. The first stage involved sorting and putting together all of the information to create codes and themes. The second step geared towards interpretation of the themes and their relationships; that is, looking for patterns, relationships and irregularities of the generated themes. Major themes developed include the structure of CTPs within the current system of tourism in Tanzania, stakeholders’ identification and involvement, benefit-sharing mechanisms and the future of CTPs in Tanzania.

4. Research findings and discussions

4.1 Cultural tourism programme structure within the current tourism system in Tanzania

Tanzania is considered to be an exceptionally scenic country that provides a wide diversity of natural attractions including 16 national parks, 34 game reserves, 38 game-controlled areas and Ngorongoro conservation area (MNRT, Citation2007). Other attractions in the country include the great Mount Kilimanjaro –Africa's highest mountain (the highest free-standing mountain in the world at 5895 metres/19 341 feet above sea level) and the ancient archaeological sites revealing the earliest traces of mankind in Olduvai George. The country is also endowed with some remarkable cultural heritage with early human settlements, especially in Bagamoyo, Rufiji, Kilwa, Kondoa and Zanzibar.

For many years, tourism activities in Tanzania have been largely focused on wildlife and scenic resources within protected areas (Akunaay et al., Citation2003). A poor infrastructural base, an inadequate communication network, and unstable energy supply and clean water supply have been cited as one of the major challenges affecting tourism development (URT, Citation2002). Despite the challenges, tourism has grown rapidly to become a major economic activity (URT, Citation1999; Kweka et al., Citation2003). In recognition of its economic importance, the government has been constantly involved in supporting the development and promotion of the industry in order to achieve its full potential (URT, Citation2002). One of the areas that continue to receive such support from the government is CTP initiatives. Tanzania is the home of about 120 ethnic groups. The fact that Tanzania has a diversity of cultures and natural resources makes CTPs a suitable tourism niche.

Most of these CTP initiatives in the country are concentrated in the northern zone (see ) where the tourism industry is well developed compared with other regions (Nelson, Citation2004; Salazar, Citation2012). Although most of the CTPs are located in rural settings, and are not owned or managed solely by communities, to a large extent they are run by outsiders who are not members of the local community. For instance, one person from CTP commented:

When we started this initiative we were four young people who came from Eastern part of the country and we had little knowledge about tourism and specifically community based tourism. After a few years two of us left. Right now I am the only active person in the initiative …

There are few people who directly benefit from our initiative because they provide home stays for tourists as well as selling their hand crafts … If you visit on market day you can also enjoy a traditional barbecue (mishikaki).

The majority of CTPs operate through a spectrum of business enterprises on one hand and community-led programmes on the other. This spectrum makes CTPs differ substantially in terms of size, structure and resource capacity. In terms of technical support, the analysis shows that old CTPs enjoyed more technical assistance than the newly established CTPs. This is because they were fewer in number during the incubation period, and hence more attention was granted to each when needed. As the number of CTPs increased, the capacity of the CTP office to provide timely support became a huge challenge. The distance from the main office and lack of resource capacity were mentioned as some of the challenges. Moreover, it was interesting to know that there was almost no communication among CTPs. Lack of cooperation and communication among various CTPs has a threatening influence on the representation and viability of these modules. Lack of communication between CTPs is verified by one interviewee, who stated that:

I don't remember when we had a meeting that involved all CTPs in the country. I am equally not sure if we will have one in a near future. The head office in Arusha has failed to facilitate this obligation … I also don't know most of them because we normally don't communicate.

4.2 Stakeholder identification and involvement

Local communitiesFootnote5 are not key stakeholders in most of the CTPs. As stipulated in many community-based guidelines and principles (Stabler, Citation1997; WWF, Citation2001; UNEP & UNWTO, Citation2005; MNRT Citation2010), stakeholder involvement is very crucial in achieving the sustainability of the CTP initiatives. In general, the principles assist in clarifying the necessity to take account and address the needs of communities in all situations regardless of the level of community ownership, control or involvement in the initiative (Simpson, Citation2008). It is argued that CBT management systems which are guided by principles are likely to build flexibility over time, allowing them to adapt and change while staying true to their initial goals and values (Murphy Citation1985; Wood Citation2002; Simpson Citation2008). Similar observations were made with regards to CTP guidelines in Tanzania. The aim of these principles is to provide guidance on protection of natural and socio-cultural resources and improve the welfare of local people, while enhancing monetary gains and market access. Many scholars argue that involvement of key stakeholders in the conceptualisation, development and daily management of a CTP initiative may assist the stakeholders (including the community) to identify, understand, appreciate and focus on those areas that are most likely to deliver net benefits to the community and vice versa (Scheyvens, Citation2002; Tosun & Timothy, Citation2003; Tosun, Citation2005 as cited by Simpson, Citation2008).

In some cases, the CTP may be initiated by one person (e.g. a local leader, an entrepreneur) or a small group of people. However, a local tourism initiative that does not have community ownership runs the risk of collapsing at any time because it will entirely depend on the interest of the owner or the manager, as exemplified in the case of Gezaulole CTP in Dar es Salaam:

Coordinators and managers of all CTP received training from SNV on how to manage CTP activities. They were then asked to formulate association where they could channel their issues – TACTO [Tanzania Cultural Tourism Organization] was then formed … The only CTP that is not operating so far is Gezaulole in Dar. The rest of CTPs are doing great. The Gezaulole CTP manager is no longer staying in Dar, so when he left, the CTP died.

Well-structured guidelines that are written in a simple and understandable language may help the key stakeholders to clearly understand their positions and the potentials they have in their local environment. The guidelines may also help the key stakeholders to understand what is appropriate and what is not appropriate for sustainable tourism development in their areas. Inappropriate tourism development and practice can degrade habitats and landscapes, deplete natural resources, damage local culture and social structure, and generate waste and pollution. In contrast, a well thought out CBT programme can help the community to generate awareness of and support for conservation and local culture, and create economic opportunities for local communities. At the time of doing this research, many CTP initiatives had no copies of the newly approved guidelines. One of the interviewees, for example, commented:

We have heard that the guidelines have been recently approved by the Minister of Natural Resources and Tourism in Dar-es-Salaam but we have not seen a copy up to this moment. We are wondering when we are going to have these copies and why it has taken so long to get them. Moreover, we are worried that the guidelines might be difficulty to understand and interpret.

The local government leaders do not understand this concept of cultural tourism. When they see the visitors around, they want to know who are they and what they are doing and always they want money (tax) from what we are doing.

4.3 Benefit-sharing mechanisms

Tourism has a high potential to be linked with other local enterprises and the capacity to fight against poverty (Mitchell et al., Citation2009). The potential for tourism to fight against poverty is praised by many scholars due to its higher multiplier effects (Kweka et al., Citation2003; Lejárraga & Walkenhorst, Citation2010:418) arguably compared with other industries. It is with these advantages that several attempts have been made to develop sustainable tourism projects including CBT, aiming at helping rural poor communities with the utilisation of their resources (Akunaay et al., Citation2003). The Tanzania Tourism Development Program, for example, indicates that ‘community based tourism is now considered a key by many development organisation in implementation of poverty eradication’ (URT, Citation2002). CBT is commended because local residents are considered to be the owners and managers of the attraction sources and services provided to tourists in their areas (WWF, Citation2001; Nelson, Citation2003, Citation2004). Responsible travel and international conservation corroborate this argument by asserting that, when establishing CBT, ‘residents earn income as land managers, entrepreneurs, service providers, and employees. CBT initiative also provides income that can be used in community development projects which benefits the community as a whole’ (MNRT, Citation2010). Such projects could be local community schools or health centres, or improving water services as well as infrastructure services.

The analysis shows that the benefits from CTP are appealing. However, the sharing mechanism is vague. For example, the decision on the percentage that has to remain in the village development fund or direct benefits to communities is open to discussion among involved members. CTPs in Tanzania are geared towards improving the livelihood of the rural communities, in essence because they gives local people an opportunity to organise tours in their surroundings, presenting their culture and lifestyle to visitors (MNRT, Citation2010). This in return provides them with both tangible and intangible benefits, as explained by one of the interviewees:

CTPs have shown good potential for directly contributing to poverty reduction through direct tour fees, jobs/salaries for local people, markets for local product (foodstuffs, handcrafts) and exposure to knowledge through interaction with tourists which increase confidence to local people.

4.4 The future of cultural tourism programmes

This question was used to explore interviewees’ perceptions about the future of CTPs in Tanzania. The information obtained revealed that all interviewees were well aware of the challenges and the potentials of CTPs in the country. With reference to challenges, interviewees mentioned poor tour guiding services, lack of technical support/training, poor communication among CTPs, and resource ownership conflict among resource stakeholders as some of the major challenges they are currently facing.

With regard to the potential of CTPs to grow, interviewees indicated that the potential for CTPs to grow and develop is high, citing that the number of tourists as well as CTPs has been growing steadily in recent years. This view is supported by the fact that in 2012 alone, eight new CTPs were registered by the ministry (TTB, Citation2013).

Regarding economic benefits, the information obtained in this research revealed that indeed CTPs can be considered as a potential means for socio-economic development and restoration of rural areas, in particular those affected by the decline of traditional agricultural systems (cf. Iorio & Corsale, Citation2010). Similarly, peripheral rural areas can be considered to be good repositories of older ways of life and cultures that respond to the postmodern tourists’ quest for authenticity (Urry, Citation2002). This view is supported by one interviewee, who argued that:

When tourists come to our areas, they help us revive our cultures and value them more. This is important not only because we make some money from tourists but they help us to sustain our cultures which otherwise would have been forgotten. Similarly, our children also get the chance to know how our ancestors lived many years ago

5. Conclusion and way forward

The current CTPs fit well within the current tourism system in the country. Although there is no clear definition of who constitutes a CTP community, the existing CTP modules differ greatly in terms of structure, size, development level and resource capacity (human, natural and cultural) and in terms of benefit-sharing mechanisms. The approved guidelines that govern the operationalisation of CTP modules in the country still have a lot of flaws, but the potential for CTPs to grow and develop is high provided the challenges are taken into consideration. The following recommendations are offered to help mitigate some of the challenges.

5.1 Improve communication, training and technical support

The information gathered in this research has revealed that there is a lack of communication among the CTPs. This study suggests that the government needs to encourage and facilitate communications among CTP ventures on a regular basis. Communication is regarded as an important tool because it provides an avenue for sharing common problems as well as means to solving them. Similarly, frequent communication can enhance the bond among CTPs and hence helps reduce the chances of unnecessary internal conflicts. Another challenge is lack of appropriate knowledge and skills on how to operate CTPs particularly the new CTPs. Training in areas such as product development, marketing, customer care, environmental pollutions and tour guiding are pertinent in operating CTPs. While the TTB and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism in general recognise that guiding skills are a major problem in many of the CTP modules, there is little happening to change the current situation. The government is mandated to find an appropriate mechanism to conduct regular training for all CTP ventures. Training in these areas and others will not only benefit people who are running these CTPs, but also will benefit the local communities and the country in general.

5.2 The need to identify stakeholders

Identification of key stakeholders is an important part of the strategic management process and certainly survival of CTPs. Attention to key stakeholders is also needed to assess and enhance the political feasibility, particularly when it comes to articulating and achieving the common good (Bryson et al., Citation2002; Campbell & Marshall, Citation2002; Eden & Ackermann, Citation2013). This study stresses paying attention to key stakeholders because practically it is not possible to satisfy all stakeholders. However, deciding who should be involved, how they should be involved and at what stage they should be involved remain a strategic choice for CTPs. Thomas (Citation1995) suggests that, in general, people should be involved if they have information that cannot be gained otherwise, or if their participation is necessary to assure successful implementation of initiatives. But this element of involvement has been ignored in the past and continues today, so it is likely that CTPs will never achieve their true potential for poverty alleviation until this changes.

5.3 Specify benefit-sharing mechanisms

The benefit-sharing mechanism is weak and needs to be constantly reviewed in order to distribute the benefits equitably. For tourism to benefit, the local communities’ proper and effective strategies to capture these tourist dollars need to be in place. If the enabling environment for tourism is poorly structured, it is likely to pave the way for a significant ‘elite capture’ of the benefits accrued from tourism. A good example of this is in cultural tourism in Cambodia and business tourism in Ghana – where less than one-tenth of tourist in-country spending reaches the resource-poor (Mitchell, Citation2012). Hence there is a need to clearly stipulate mechanisms that accrued benefit is going to be shared without giving loop holes for exploitation.

Notes

5From the CTP guidelines, communities are defined based on their geographical location where the CTP activities take place.

References

- Akunaay, M, Nelson, F & Singleton, E, 2003. Community based tourism in Tanzania: Potential and perils in practice. Paper presented at the 2nd IIPT African Conference on Peace through Tourism, 7–12 August, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- Belsky, JM, 1999. Misrepresenting communities: The politics of community-based rural ecotourism in Gales Point Manatee, Belize. Rural Sociology 64(4), 641–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.1999.tb00382.x

- Blackstock, K, 2005. A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal 40(1), 39–49. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsi005

- Boyd, SW & Singh, S, 2003. Destination communities: Structures, resources and types. In Singh, S, Timothy, DJ & Dowling, RK (Eds.), Tourism in destination communities. CAB International, Oxford, England, pp. 19–33.

- Bryson, J, Cunningham, G & Lokkesmoe, K, 2002. What to do when stakeholders matter: The case of problem formulation for the African American men project of Hennepin County Minnesota. Public Administration Review 62(5), 568–84. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00238

- Caalders, J & Cottrell, S, 2001. SNV and sustainable tourism: A background paper. Netherlands Development Organisation, The Hague.

- Campbell, H & Marshall, R, 2002. Utilitarianism's bad breath?. A re-evaluation of the public interest justification for planning. Planning Theory 1(2), I63–87. doi: 10.1177/147309520200100205

- De Jong, A & Liejzer, M, 1999. Cultural tourism in Tanzania: Experiences of a tourism development project. Netherlands Development Organisation, The Hague.

- Eden, C & Ackermann, F, 2013. Making strategy: The journey of strategic management. Sage, Thousand Oaks, California.

- Galdini, R, 2007. “Tourism and the city: Opportunity for regeneration”, MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive, MPRA Paper No. 6370. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/6370 Accessed 13 December 2013.

- Gale, T, 2006. Finding meaning in sustainability and a livelihood based on tourism: An ethnographic case study of rural citizens in the Ayse'n region of Chile. PhD Thesis, West Virginia University, USA.

- Hall, CM, 1999. Rethinking collaboration and partnership: A public policy perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 7(3), 274–89. doi: 10.1080/09669589908667340

- Hibbard, M & Lurie, S, 2000. Saving land but losing ground challenges to community planning in the era of participation. Journal of Planning Education and Research 20(2), 187–95. doi: 10.1177/0739456X0002000205

- Hughes, H, 1996. Redefining cultural tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 23(3), 707–9. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(95)00099-2

- Iorio, M & Corsale, A, 2010. Rural tourism and livelihood strategies in Romania. Journal of Rural Studies 26(2), 152–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.10.006

- Jamal, TB & Getz, D, 1995. Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research 22(1), 186–204. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

- Kepe, T, 1999. The problem of defining ‘community’: Challenges for the land reform programme in rural South Africa. Development Southern Africa 16(3), 415–33. doi: 10.1080/03768359908440089

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N, 2005. Community-based ecotourism in phuket and Ao phangnga, Thailand: Partial victories and bittersweet remedies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 13(1), 4–23. doi: 10.1080/17501220508668470

- Kweka, J Morrissey, O & Blake, A, 2003. The economic potential of tourism in Tanzania. Journal of International Development 15(3), 335–51. doi: 10.1002/jid.990

- Lejárraga, I & Walkenhorst, P, 2010. On linkages and leakages: Measuring the secondary effects of tourism. Applied Economics Letters 17(5), 417–21. doi: 10.1080/13504850701765127

- Lukkarinen, M, 2005. Community development, local economic development and the social economy. Community Development Journal 40(4), 419–24. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsi086

- Manyara, G & Jones, E, 2007. Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(6), 628–44. doi: 10.2167/jost723.0

- Mclain, R & Jones, E, 1997. Challenging ‘community’ definitions in sustainable natural resource management: The case of wild mushroom harvesting in the USA. IIED, London, UK.

- Michael, M Mgonja, JT & Backman, KF, 2013. Desires of community participation in tourism development decision making process: A case study of Barabarani, Mto wa Mbu, Tanzania. American Journal of Tourism Research 2(1), 84–94. doi: 10.11634/216837861302319

- Miles, MB & Huberman, AM, 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

- Mitchell, J, 2012. Value chain approaches to assessing the impact of tourism on low-income households in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 457–75. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2012.663378

- Mitchell, RE & Reid, DG, 2001. Community integration: Island tourism in Peru. Annals of Tourism Research 28(1), 113–39. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00013-X

- Mitchell, J, Keane, J & Laidlaw, J, 2009. Making success work for the poor: Package tourism in Northern Tanzania. ODI and SNV, Arusha, Tanzania.

- MNRT (Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism), 2007. Tanzania wildlife policy. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

- MNRT (Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism), 2010. Guidelines for cultural tourism in Tanzania. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

- Murphy, P, 1985. Tourism a community approach. Methuen, New York.

- Nelson, F, 2003. Community-based tourism in Northern Tanzania: Increasing opportunities, escalating conflicts and an uncertain future. In Wishitemi, B, Spenceley, A & Wels, H (Eds.), (2007). Culture and community: Tourism studies in Eastern and Southern Africa. Rozenberg Publishers.

- Nelson, F, 2004. The evolution and impacts of community-based ecotourism in northern Tanzania (Issue Paper No. 131). IIED: London, UK.

- Nelson, F, 2007. Community-based tourism in Northern Tanzania: Increasing opportunities, escalating conflicts and an uncertain future. In Wishitemi, B, Spenceley, A & Wels, H (Eds.), Culture and community: Tourism studies in Eastern and Southern Africa. Rozenberg Publishers, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 104–20.

- Page, SJ & Dowling, RK, 2002. Ecotourism. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, England.

- Paniagua, A, 2002. Urban–rural migration, tourism entrepreneurs and rural restructuring in Spain. Tourism Geographies 4(4), 349–71. doi: 10.1080/14616680210158128

- Patton, MQ, 2002. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, California.

- Pearce, DG, 1992. Alternative tourism: Concepts, classifications, and questions. In Smith, VL & Eadington, WR (Eds.), Tourism alternatives: Potentials and problems in the development of tourism. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 15–30.

- Pretty, J, 1995. The many interpretations of participation. Focus, 16, 4–5.

- Rozemeijer, N, 2001. Community-based tourism in Botswana: The SNV experience in three community-tourism projects. SNV Botswana, Gaborone.

- Salazar, NB, 2012. Community-based cultural tourism: Issues, threats and opportunities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(1), 9–22. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.596279

- Scheyvens, R, 1999. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management 20, 245–9. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00069-7

- Scheyvens, R, 2002. Tourism for development: Empowering communities. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, England.

- Selznick, P, 1996. In search of community. In Vitek, W & Jackson, W (Eds.), Rooted in the land: Essays on community and place. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 195–206.

- Silberberg, T, 1995. Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites. Tourism Management 16(5), 361–5. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(95)00039-Q

- Simpson, MC, 2008. Community benefits tourism initiatives: A conceptual oxymoron?. Tourism Management 29(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.005

- Smith, MK, 2007. Towards a cultural planning approach to regeneration. In Smith, M. (Ed.), Tourism, culture and regeneration. CAB International, Wallingford. pp. 1–11.

- Snyder, KA & Sulle, EB, 2011. Tourism in Maasai communities: A chance to improve livelihoods. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(8), 935–51. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.579617

- Sofield, T & Birtles, A, 1996. Indigenous peoples’ cultural opportunity spectrum for tourism (IPCOST)’. In Butler, R & Hinch, T (Eds.), Tourism and indigenous peoples. Routledge, London. pp. 396–432.

- Stabler, MJ (Ed.) 1997. Tourism and sustainability: Principles to practice. CAB International, New York.

- Swarbrooke, J, 1999. Sustainable tourism management. CAB International, Oxford, England.

- Taylor, G, 1995. The community approach: Does it really work?. Tourism Management 16, 487–9. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(95)00078-3

- Thomas, JC, 1995. Public participation in public decisions. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

- Tosun, C, 1999. Towards a typology of community participation in the tourism development process. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality 10, 113–34.

- Tosun, C, 2000. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management 21, 613–33. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

- Tosun, C, 2005. Stages in emergence of participatory tourism development process in developing countries. Geoforum 36(3), 333–52. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.06.003

- Tosun, C, 2006. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management 27, 493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.12.004

- Tosun, C & Timothy, DJ, 2003. Arguments for community participation in the tourism development process. Journal of Tourism Studies 14(2), 2–14.

- TTB (Tanzania Tourist Board), 2013. Tanzania cultural tourism program. http://tanzaniaculturaltourism.go.tz/docs/new_cultural.pdf Accessed 13 December 2013.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) & UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization), 2005. Making tourism more sustainable: Guide for policy makers. http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/pdf/DTIx0592xPA-TourismPolicyEN.pdf Accessed 13 December 2013.

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization), 2003. Tourism highlights. UNWTO, Madrid, Spain.

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization), 2004. Indicators of sustainable development for tourism destinations: A guidebook. UNWTO, Madrid, Spain.

- Urry, J, 2002. The tourist gaze. Sage, London.

- URT (United Republic of Tanzania), 1999. Tanzania national tourism policy. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

- URT (United Republic of Tanzania), 2002. Tanzania tourism master plan. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

- URT (United Republic of Tanzania), 2010. Tanzania cultural tourism program. http://tanzaniaculturaltourism.go.tz/ Accessed January 2014.

- Wood, ME, 2002. Ecotourism: Principles, practices and policies for sustainability. UNEP, Paris, France.

- WWF (World Wildlife Fund), 2001. Guidelines for community-based ecotourism development. WWF International, Gland, Switzerland.

- Wyllie, R, 1998. Hana revisited: Development and controversy in a Hawaiian tourist community. Tourism Management 19, 171–8. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00109-X