Abstract

This paper responds to the paucity of research on the linkages between voluntourism and digital technology and seeks to understand the online representation of the phenomenon in a developing context. In particular, the researchers investigate the so-called ‘online domain’ of voluntourism in South Africa. The researchers collected a series of web results from search engines and analysed the presence of traditional and social media websites, the most relevant presented topics, and the type of argumentation found. Results identify the context and representation of voluntourism as it transpires virtually. This will contribute to the understanding of the interplay between voluntourism and digital technology, with specific emphasis on web presence. Ultimately, results will shed light on how digitally accessible voluntourism is in South Africa and will set the basis for future investigations.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a driving force in many developing economies and contributes significantly to gross domestic product (Sireyjol, Citation2010). Tourism can also positively affect the development of emerging societies, and can assist in social and cultural diversification (Wang & Pfister, Citation2008; Herrero & San Martín, Citation2012). But while tourism offers several developmental benefits in terms of environmental sustainability, poverty reduction, education and healthcare, the nature of such contributions remains uncertain (Deller, Citation2010). Indeed, tourism also has controversial implications for natural resources and marginalised groups, notably in the Global South. It is in this context that vying organisations exploit and monopolise both social and natural capital under the guise of ‘tourism’ (Deller, Citation2010). Exploitative tourism has long been contested (Krippendorf, Citation1987), and alternative forms gradually arose with a renewed focus on sustainability and local development. Alternative tourism is an ideologically different form of tourism that is considered preferable to mass, consumer-driven and exploitative forms (Wearing, Citation2001).

Voluntourism (or volunteer tourism) is seen as a mode of alternative tourism (Callanan & Thomas, Citation2005) and promotes the altruistic values of volunteering, which generally involves partaking in for-good causes that support social and environmental upliftment in marginalised communities (Wearing, Citation2001). Voluntourism is thus considered more personally rewarding and meaningful at a communal level than mass or mainstream tourism: travel and philanthropy converge to support local and international development initiatives (see Stoddart & Rogerson, Citation2004). Voluntourism is ideally seen to foster a reciprocal and mutually beneficial relationship between hosts and guests (Wearing, Citation2001). However, like traditional tourism, it can also lead to exploitation and power disparities, which may infringe on the freedoms and values of local groups.

There is a growing body of literature in the tourism field in respect of the complex relationship between volunteers (McGehee, Citation2002; Brown & Morrison, Citation2003) and hosting communities (Clifton & Benson, Citation2006; McGehee & Andereck, Citation2009). Despite this, no research to date has examined how the Internet mediates voluntourism experiences. This aspect is of interest due to the growing significance of the Internet both in tourism experience planning (Buhalis & Law, Citation2008) and in socio-economic development (Unwin, Citation2009). Indeed, the emerging global state of hyperconnectivity, fundamentally driven through the Internet, is reshaping the traditional dynamics of tourism and its relationships with tourist-consumers, enterprises and communities (Bilbao-Osorio et al., Citation2013).

In this study, we assess the online representation of voluntourism in a given country, namely South Africa. Theoretically, this research is framed within the work of Xiang et al. (Citation2008) and of Xiang & Gretzel (Citation2010), who investigate the so-called ‘online tourism domain’ accessible through search engines, highlighting its structure and composition. Methodologically, the research is based on the work of Inversini et al. (Citation2009) and Inversini & Cantoni (Citation2011) in which a structured, qualitative content analysis (Riffe et al., Citation1998) was used to analyse a series of webpages collected on popular search engines.

Our aim is to map the context and representation of voluntourism as it transpires virtually in a South African context. To do so, we identified a series of relevant keywords (e.g. Jansen et al., Citation2008) related to voluntourism in the country and queried the popular search engine Google.com with each keyword. A series of web results were collected, stored and analysed, specifically illuminating the presence of traditional and social media websites, the most relevant presented topics, and the type of argumentation found. The research is framed within the theoretical domain of online information search (Jang, Citation2004) and is operationalised in the context of tourism, and specifically the context of voluntourism (in which there is a paucity of technology-oriented research; e.g. Nyahunzvi, Citation2013).

2. Context

In what follows, our literature review assimilates four areas of inquiry: a critical review of the concept of voluntourism; voluntourism and its relation to development and the cultural economy; the status of voluntourism in South Africa; and the significance of information search in the context of the online domain. From a collective review of these areas, we deduce an under-explored yet emerging theme (i.e. the interplay between digital technologies and voluntourism), which sets the foundation for an empirical exploratory study.

2.1 Voluntourism

Voluntourism is defined in industry as ‘a seamlessly integrated combination of voluntary service to a destination along with the best, traditional elements of travel – arts, culture, geography, and history – in that destination’ (voluntourism.org, n.d.). In academia, in the seminal work of Wearing, it is defined as:

a type of alternative tourism in which tourists volunteer in an organised way to undertake holidays that might involve aiding or alleviating the material poverty of some groups in society, the restoration of certain environments or research into aspects of society or environment. (Wearing, Citation2001:1)

Voluntourism is an expanding sector of the tourism industry (Bakker & Lamoureux, Citation2008) and can be categorised under ‘alternative tourism’ and/or ‘ethical consumerism’. It is widely accepted that voluntourism should generate a positive impact for locals in host destinations, and a mutually beneficial host–guest relationship in a tourist destination (Sin, Citation2010). Nonetheless, despite the growing body of research in the field (Lupoli et al., Citation2014; Smith & Font, Citation2014), most studies focus on volunteers, examining their motivations and experiences (Wearing & McGehee, Citation2013). Few studies to date (McGehee & Andereck, Citation2009) discuss the role of voluntourism and its implications for host communities in depth (e.g. Clifton & Benson, Citation2006). This is unexpected because of the exploitative practices and marginalisation of local hosts that are often associated with commercial tourism (Pastran, Citation2014).

The effects of voluntourism on local communities should be studied in more depth, with stronger monitoring and evaluation (Taplin et al., Citation2014). As Butcher (Citation2011) underlines, there is a lack of substantial benefit for hosts, and this is not addressed in current research. Guttentag (Citation2009) argues for a critical approach towards voluntourism and questions the idealistic depiction of the sector in many existing studies. Voluntourism is in fact often characterised by ‘a romantic view of poverty, and in the academic discussion, a strong post-development outlook’ (Butcher, Citation2011:75). Similarly, due to the great variety of volunteer tourism experiences on offer, the industry has become ‘increasingly ambiguous in definition and context’ (Callanan & Thomas, Citation2005:195). This is coupled with the rapid expansion and commercialisation of the sector (Guttentag, Citation2011).

Volunteer tourism projects are often conceived in a detached, economically driven manner; that is, by not considering the real needs, complexities and situated contexts of host communities (Raymond, Citation2011). For Mostafanezhad & Kontogeorgopoulos (Citation2014), voluntourism should be driven from the grassroots and the tourism industry should develop (volunteer-related) policies to contribute more positively to the overall voluntourism experience. Thus, without a shift in the formulation and marketisation of voluntourism (i.e. by organisations and actual volunteers), the sustainability of volunteer projects in developing contexts could be undermined (Lyons & Wearing, Citation2008).

2.2 Voluntourism, development and the cultural economy

By its high-level definition, voluntourism as a form of sustainable tourism is conceived around three intersecting domains: the environment, the economy, and culture (Cheong, Citation2008:11). The environmental domain concerns the productive use of natural resources without impeding the use of those same resources for future generations. This extends to the protection of natural heritage and biodiversity. The economic domain concerns that which creates or supplements income-generation through tourism, and ensuring that there is equitable access to the tourism economy. Finally, the culture domain entails a respect for local custom and the promotion of intercultural understanding (Cheong, Citation2008:11).

There is in this vein a clear developmental aim in the concept and practice of voluntourism. This is not always determinable in the actual ‘push and pull’ motivations of voluntourists (Daldeniz & Hampton, Citation2010), who may embark on volunteer tourism activities for a diversity of reasons. Some of the push factors include altruistic motives (the desire to travel with a purpose) or personal ambitions (such as self-enhancement, professional development, and the desire for social interaction or independence). Pull factors foster the individual's desire to travel and explore other parts of the world, underlining the importance of destination marketing and its power to create perceived images within potential volunteer-tourists. Indeed, volunteers are heavily influenced in their decision-making by the representations of destinations portrayed in promotional materials (including websites; Daldeniz & Hampton, Citation2010:8).

Despite personal, economic or touristic motivations, voluntourism is still largely a stimulus for community and regional development, intrinsically tied to travel (Daley, Citation2013). One of its largest development markets, not limited to the Global South, is the heritage industry, otherwise referred to as the cultural economy. Indeed, with mass production and consumption brought on by globalisation, the demand for cultural goods and services has surged. Consequently, the marketisation of culture has become a lucrative global enterprise for tourists, volunteers, destination marketers, and consumers (Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2009). Historical examples of survivalist cultural economies (Parnaby, Citation2008) indicate the commercial value a ‘culture’ can have in contemporary society. As Pratt (Citation2007:5–6) observes, ‘cultural products, once the realm of “one offs” and “live performance”, are now readily reproducible millions of times (for the same economic input)’. This has sparked a batch of creative producers, wishing to craft livelihoods from their cultural ‘uniqueness’. Ultimately, the cultural economy is one where local communities have come to position themselves in global market form, optimised for tourist consumption. Cultural enterprises negotiate their value in economic terms and have to produce, package, brand, sell, profit and distribute accordingly (Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2009).

With its simultaneous promise of authentic travel and local development, the culture industry (Adorno, Citation1991) becomes deeply embedded in the voluntourism enterprise. It is in this context that local communities capitalise on the seemingly exotic qualities of their cultural and natural heritage – a distinctive ‘otherness’. Such uniquely cultural features are marketed to outsiders (tourists, volunteers, consumers) to generate income, sustain natural resources, and garner interest in local upliftment initiatives (see Lacey et al., Citation2012). It is against this background of cultural commodification that voluntourism is also seen as a controversial practice, precisely because of its exploitative (and self-commoditising) implications for local groups.

2.3 Voluntourism in South Africa

South Africa is one of the top destination choices for voluntourists and the responsible tourism industry in the country is well regulated. In 2002, 280 representatives from 20 countries signed a historic declaration at the Cape Town Conference on Responsible Tourism in Destinations. This formed the basis for responsible tourism in the country and included several key directives (adapted from Alexander, Citation2012:48):

generating greater economic benefits for local people and enhancing the well-being of host communities;

improving working conditions and access to the industry;

involving local people in decisions that affect their lives and life chances;

making positive contributions to the conservation of natural and cultural heritage;

providing more enjoyable experiences for tourists through meaningful connections with local people; and

promoting a greater understanding of diversity, local culture, social and environmental issues.

In 2011, the Department of Tourism published the ‘National Minimum Standard for Responsible Tourism'. This was created to establish a common understanding of responsible tourism, and to be the baseline standard for tourism businesses in the country (SADT, Citation2012). The ‘National Minimum Standard for Responsible Tourism' consists of 41 criteria for local tourism organisations (operators, destination marketers, non-profit organisations) to be used as benchmarks for responsible tourism goals (Alexander, Citation2012). Similar organisational initiatives have included Fair Trade in Tourism South Africa, established to certify South African tourist organisations that benefit local communities, and that operate in ethically, socially and environmentally responsible ways (Alexander, Citation2012).

Despite the increased recognition of responsible tourism in South Africa, there is a shortage of literature on the many aspects and implications of volunteer tourism in the country. Indeed, tourism studies undertaken here are fragmented, spanning a range of topics such as cultural tourism, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender tourism, wine tourism, ecotourism, and backpacker tourism (Alexander, Citation2012). Supported through the growing body of literature (e.g. Smith & Font, Citation2014; Taplin et al., Citation2014), voluntourism can be considered a promising and interesting research area in the Southern African context. Furthermore, the online domain of voluntourism is unexplored in the academic literature, and this relates particularly to issues of its visibility and accessibility through search engines.

2.4 Information search and voluntourism

There is a lack of research in voluntourism literature on the role and impact of digital technology, and in particular the Internet (Nyahunzvi, Citation2013). In this context, special attention should be given to search engines as the preferred gateway to online information (Cilibrasi & Vitanyi, Citation2007). The Internet can be seen as a complex and interrelated collection of webpages (Baggio et al., Citation2007). Therefore, locating or pinpointing relevant information within this grand network becomes a critical task (Hecht et al., Citation2012). This concerns the issue of online information search, which has attracted the interest of academics and practitioners in the last decade (e.g. Jang, Citation2004).

A central issue in information search is the possibility of locating correct and relevant information in the online domain (Xiang et al., Citation2008). Search engines are the fundamental entry points to online material and their results even shape the way users perceive the available information. A study by Xiang et al. (Citation2008) defined the so-called online tourism domain as the collection of webpages that are relevant for a given tourism query through search engines. This is populated by different webpages dealing with destination content and consists of a given number of domains (i.e. most search engine results are domain duplicates). Moreover, the online tourism domain is not highly accessible: only a small percentage of indexed pages are obtainable by end users. This is because, despite a high number of search results, only 1000 results per query are actually visible to Internet users. In the case of the online tourism domain, the visibility ratio (i.e. the actual percentage of accessible webpages) is 0.032% of the total indexed pages (Xiang et al., Citation2008).

A study by Xiang & Gretzel (Citation2010) indicated that social media also populate search engine results. Indeed, social media have been increasingly absorbed within the search engine listing (Gretzel, Citation2006). This is particularly relevant for a sector such as tourism, where the decision-making process is (also) based on the experiences of others (Gretzel & Yoo, Citation2008). Additionally, research has demonstrated that social media incorporate similar content to traditional websites, but with different representational strategies (Inversini & Buhalis, Citation2009). Traditional websites – websites that do not incorporate interactive features typical of social media and are managed by an editorial staff rather than being populated by users (Inversini et al., Citation2009) – tend to portray a neutral or positive image (e.g. of a destination). Social media websites, conversely, encompass media impressions created by consumers, typically informed by subjective experiences, and shared online for easy access by other impressionable consumers (Blackshaw, Citation2006).

Such impressions are a mixture of facts and opinions, emotions, impressions and sentiments, experiences, and even rumours (Blackshaw & Nazzaro, Citation2006), ultimately characterised by a variety of feelings expressed by contributors (Inversini et al., Citation2009). It becomes pertinent, then, to consider social media in the online tourism domain, and especially how it relates to the topic of voluntourism. This pertains specifically to its visibility, its representation of content, and the sentiments that are expressed through it.

3. Research design

We collected a series of web results from search engines based on the existing literature dealing with information search (e.g. Pan & Fesenmaier, Citation2006). Our research design is theoretically based on the work of Xiang et al. (Citation2008) and Xiang & Gretzel (Citation2010), who investigated the structure and composition of the online tourism domain in a statistical manner. Methodologically, the research employs content analysis: we analysed search engine results in an interpretive, qualitative manner using a codebook as already conducted in the field of tourism by Inversini et al. (Citation2009). Through this research design, we created an exploratory setting to understand the type of information presented in the search engine results. These findings help describe the respective information providers, topics discussed, and type of communication in respect of voluntourism. We selected the South African context as a case study due to it being one of the most popular African destinations for both travel and volunteering (as exemplified by the TripAdvisor Award of 2013).

Overall, this research was designed to investigate the online domain of voluntourism in South Africa, addressing the following research questions:

Question 1: What is the composition of the online voluntourism domain?

Question 2: What are the voluntourism topics covered in the search engine listing?

Question 3: What ‘feelings’ do the retrieved webpages express about voluntourism?

3.1 Data collection

Search queries reflect a diversity of user goals that can include navigational goals (looking for a specific webpage), informational goals (trying to obtain a piece of information), and transactional goals (carrying out a certain task or activity) (Jansen & Molina, Citation2006). Jansen et al. (Citation2008) found that user queries are largely informational (81%), followed by navigational tasks (10%) and transactional tasks (9%). This study is based on informational queries as the predominant form of searching.

Furthermore, in travel and tourism, recent studies indicate that traveller queries tend to be concise, typically consisting of less than four keywords (Jansen et al., Citation2008). Most travellers do not go beyond the results provided on the second or third page of a search engine (Inversini et al., Citation2009). A US study claimed that online searchers usually focus on cities as the geographical delimiter instead of states or countries (Pan et al., Citation2007). Additionally, travellers often combine their searches for accommodation with other aspects of the trip, including dining, attractions, destinations, or transportation (Xiang et al., Citation2008).

Following the aforementioned criteria, we created three sets of keywords to analyse the online domain of voluntourism in South Africa. For each keyword, we stored and analysed the first 30 results (i.e. first three search pages). The first set of keywords described the generic phenomenon of voluntourism in South Africa:

[K1] ‘volunteer and tourism South Africa’

[K2] ‘voluntourism South Africa’

The second set of keywords related to possible voluntourism activities in South Africa. These were adapted from the United Nations Development Programme and its Human Development Report (UNDP, Citation2013). The use of ‘volunteer and tourism’ was preferred to the use of ‘voluntourism’ to enhance the descriptive power of the online search. The selected keywords here included:

[K3] ‘volunteer and tourism Community Development South Africa’

[K4] ‘volunteer and tourism Human Rights South Africa’

[K5] ‘volunteer and tourism Health South Africa’

[K6] ‘volunteer and tourism Education South Africa

[K7] ‘volunteer and tourism Heritage South Africa’

[K8] ‘volunteer and tourism Environment South Africa’

[K9] ‘volunteer and tourism Technology South Africa’

[K10] ‘volunteer and tourism Youth Development South Africa’

[K11] ‘volunteer and tourism Social Protection South Africa’

The third set of keywords was geographically related (capital cities of each of the nine provinces in the country):

[K12] ‘volunteer and tourism Cape Town’

[K13] ‘volunteer and tourism Mahikeng’

[K14] ‘volunteer and tourism Kimberley’

[K15] ‘volunteer and tourism Mbombela’

[K16] ‘volunteer and tourism Polokwane’

[K17] ‘volunteer and tourism Pietermaritzburg’

[K18] ‘volunteer and tourism Johannesburg’

[K19] ‘volunteer and tourism Bloemfontein’

[K20] ‘volunteer and tourism Bisho’

In January 2014, we collected data by means of the popular search engine Google.com, which in the same month had a 71.32% market share of desktop searches (Net Market Share, Citation2014).

3.2 Data analysis

In respect of the designed queries, we collected 600 webpage addresses. Only the first three pages of the result listing were considered relevant for this research (as is the benchmark; iProspect, Citation2006). Collected results (20 keywords × 30 search results each = 600 total search results) were stored and interpreted using a codebook as an instrument for content analysis (Riffe et al., Citation1998). The analysis was structured along two sections. Section A described the general nature of the search results (see Inversini et al., Citation2009):

Website types (traditional or social – destination websites are a standard example of traditional websites and blogs are a standard example of social websites).

Detailed website type (e.g. consumer review, newspaper, destination site).

Website topics and frequency (tourism, volunteering, and voluntourism).

Detailed content types (e.g. informative/factual, advertisement, comment/review).

Section B described a series of additional but significant aspects, namely: the nature of the arguments presented (from purely factual to purely emotional, measured on a scale from zero to five; Inversini, Citation2011); the feelings expressed by such arguments (from purely negative to purely positive, measured on a scale from zero to five; Inversini, Citation2011); and the level of engagement for visitors/users (from no engagement to active engagement, measured on a scale from zero to four; Li, Citation2010). The need for having a Likert scale for these categories is related to the fluctuating nature of the information retrieved. Traditional websites (e.g. a destination website) often present positive factual and informative content with no level of engagement (Inversini & Cantoni, Citation2011). Conversely, social media often contain emotional content with different expressed feelings (ranging from purely positive to purely negative) with varying levels of engagement (Inversini et al., Citation2009).

However, website content may be partly informative and partly emotional and may express different feelings. Therefore, coders were asked to interpret the predominant characteristic of the content on the specific Likert scale. Foreseeably, individual coders perceived characteristics differently; therefore, all coders discussed their interpretations of the code scale to reach consensus in recognising and interpreting the proposed content. Following this, inter-coder reliability was calculated using the Fleiss Kappa method (Fleiss, Citation1971; Sim & Wright, Citation2005), resulting in 0.87. This calculation was necessary to maintain a high level of agreement among coders.

4. Results

4.1 Keyword relevance

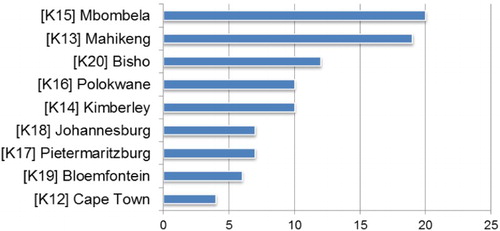

Among the collected search engine results, 17.8% (n = 107) was either faulty (link not working) or irrelevant (webpage did not reference voluntourism). The final sample of websites for the analysis consisted of 493 search engine results (n = 493). Searches using geographical keywords (see ) resulted in more instances of faulty and irrelevant websites. Conversely, searches using activity-based keywords generally listed more functional and relevant sites.

Table 1: Faulty and irrelevant results

For geographical searches, larger (or better known) cities such as Cape Town list more relevant and working results than smaller or lesser-known cities ().

4.2 Type of websites

Results were dominated by traditional websites (87%), the majority of which belonged to voluntourism organisations (27.5%). The percentage of each website type is presented in .

Table 2: Website types

Fifteen domains dominated the search results listing, representing 28.8% of the overall analysed results. The most popular domains in the sample are: southafrica.info (n = 35), tripadvisor.com (n = 23), africanimpact.com (n = 16), backpackingsouthafrica.co.za (n = 12), linkedin.com (n = 10), gooverseas.com (n = 10), and voluntourism.org (n = 10).

4.3 Website topics and frequency

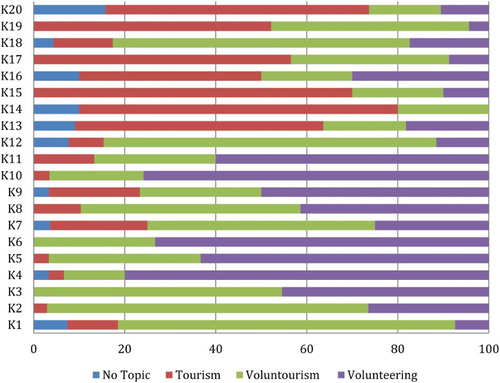

Most of the surveyed websites present topics about volunteering (36.60%) or voluntourism (42.80%). Only one out of five search results present content solely about tourism ().

Table 3: Website topics presented

For generic keywords (K1 and K2), a predominance of topics deal with voluntourism (70.07% and 70.58% respectively). The second group of activities keywords (from K3 to K11) lists a predominance of volunteering topics, with the exception of K7 ‘volunteer and Tourism Heritage South Africa’ and K8 ‘volunteer and Tourism Environment South Africa' which present topics about voluntourism (50% and 48.27% respectively). The geographical keywords (K12 to K20) list more results about tourism, with the exception of K12 ‘volunteer and Tourism Cape Town’ and K18 ‘volunteer and Tourism Johannesburg’ which present topics about voluntourism (73.07% and 65.21% respectively) ().

4.4 Typology of content

Most of the analysed websites present informative content (78%) with long text (86%). also indicates the small number of social/interactive websites present within the sample. Comment/review websites as well as pictorial and discussion group websites represent a small proportion of the overall sample.

Table 4: Typology of content

4.5 Type of arguments and feelings

Website topics are covered mostly in a fully factual way (24.9%), although 57.6% of results indicate mixed factual and emotional arguments. Regarding the overall ‘feeling’ for each website, a general tendency to be positive (63.23%) was recorded. A total 28.6% of the analysed results did not present any observable feelings and were mostly informative in nature. The remaining 71.4% (n = 352) of results presented mostly positive feelings. presents the breakdown of feelings among website types and topics.

Table 5: Feelings for each topic

In terms of social media websites, users do express positive feelings about tourism, voluntourism and volunteering (). Traditional websites also present feelings in order to persuade prospective travellers and volunteers to enrol in such experiences. This is interesting as the critical lens of volunteering modifies the usual communication strategies of tourism websites (i.e. no feelings are typically expressed on traditional websites; Inversini et al., Citation2009). The level of engagement is absent or low (83.6%), thus demonstrating the weak presence of social media websites.

5. Discussion

From these results, we observed that the most relevant voluntourism websites are not derived from geographical keywords. This contradicts tourism literature (e.g. Pan et al., Citation2007), as geographical keywords in this study are mostly unrelated to useful voluntourism content. We hypothesise that this is due to changing travel motivations, where the type of volunteering activities (or individual ambitions) are more relevant than specific locations. Indeed, voluntourism does bring an important social aspect to the travel motivations of tourists, and such aspects may become more pertinent when searching for possible volunteering experiences.

Furthermore, this may provide some initial evidence that the geographic locations (provincial capital cities) are presently unknown or unpopular voluntourism destinations. Many of these cities – apart from Cape Town and Johannesburg – seem unconnected to voluntourism activities, at least in terms of online presence, visibility, and accessibility (refer to and ). However, the strong presence of destination websites (especially southafrica.info, with a frequency of 35 domain counts) indicates that there is a growing content base at national level concerning voluntourism. Most of the pages from this website promote volunteering as a form of alternative tourism in the country. Pages here also highlight the many possibilities of volunteering in South Africa and provide tips and incentives for joining these experiences.

Additionally, there is a lesser presence of social media websites within our sample. Only 12.99% of the analysed websites are related to the social media categories defined within our codebook (see ). In fact, most of the analysed websites present informative content (78.70%, ) with long text, with minimal social and engaging (Web 2.0) content. This is in line with the findings of Xiang & Gretzel (Citation2010), who described a social media representation of 11% in their research. However, due to the rapid emergence and popularity of social media in the tourism industry, we expected to find a higher presence in our sample. Therefore, it is possible to claim that voluntourism in South Africa is more significantly represented by traditional websites than by social media.

The topics discussed within the search results () are grouped along tourism (20.60%), volunteering (36.60%) and voluntourism (42.80%). Strangely, the nature of the results is a mixture of factual and emotional arguments (57.60%). This demonstrates that, although the results are largely informative/factual and not based on social (or Web 2.0) content, informative items do incorporate some emotional content to communicate information about voluntourism. This contradicts previous research in the tourism field where non-social media websites are seen to convey only informative and factual content (Inversini et al., Citation2009). However, this may reflect the nature of the domain investigated, where social issues related with volunteering and travel motivations need to be substantiated by or promoted through emotional content.

Moreover, it is observed that traditional websites mostly present positive content about the topic of volunteering (27.99%, ). This is arguably to introduce and promote the practice toward target audiences more effectively, as it may be an unfamiliar topic or experience to most visitors. However, social media websites mostly present positive content about tourism. Because social media sites are often for commenting on lived experiences (e.g. Blackshaw & Nazzaro, Citation2006), this may indicate that persons who underwent the actual voluntourism experience comment (almost uniquely) about tourism in a good way (3.45%, ), and not about volunteering.

5.1 The online domain of voluntourism

The aforementioned results have helped to address our respective research questions. In terms of Question 1, the composition of the online domain, we observe the essentially ‘traditional’ landscape of the voluntourism search listing (). The majority of websites – mostly voluntourism organisations – exhibit Web 1.0 characteristics: static user interfaces and limited or no user-generated content. Voluntourism is also accessible as a topic using a variety of keywords, although geographical keywords are the least definitive in finding relevant voluntourism information. Generic and activity-driven keywords are more effective in searching for relevant experiences (but may vary in topic). Aside from shifting travel motivations, this may be simply due to the unique and relatively unfamiliar concept of voluntourism: users look for informative content before considering actual, geographically based projects.

As for Question 2, voluntourism organisations do seem strongly represented in the search listing, and the topic of voluntourism is equally accessible – along with tourism and volunteering – among such sites (). Of course, topic frequency varies for each keyword. The topic of voluntourism is more accessible using generic or single keywords than it is using geographical and activity qualifiers. Irrespective of keyword, the search engine listing is largely informative/informational, with limited social or user-generated content (). Although in agreement with the literature, this is slightly surprising given the increasing prevalence of social media in South Africa and globally.

Considering Question 3, the majority of webpages indicate mixed factual and emotional arguments, followed by mostly positive feelings. This is despite the largely informative basis of the search listing. As explained, this may be due to the intersecting components of voluntourism as not only a singular travel experience, but also a complex development activity. In this case, purely factual information might betray the development aspect as an emotionally and socio-culturally dynamic activity. Positive feelings also strengthen the marketing value of voluntourism as a rewarding and highly beneficial activity for tourist-volunteers.

6. Concluding thoughts

This research has helped to illuminate the composition of the online domain of voluntourism in South Africa as an emerging sector in the responsible tourism landscape. Given the exploratory and interpretivist nature of this research, results are limited to this context. Future research may look to explore the composition of this domain in other countries and regions with a similar methodology. Overall, voluntourism in South Africa is digitally accessible as a topic in the web domain, and users will probably find content that suits their needs. However, voluntourism is limited in other respects: content is largely informative, topics do not generally consider voluntourism exclusively, social engagement is low and user-generated content is limited. Consequently, voluntourism has not penetrated the social domain effectively, which renders it outside a large and active user base. This may further inhibit voluntourism as an agent of development and the local cultural economy, as it is not mediated effectively through online means.

Theoretically, this research sheds light on the online representation of voluntourism in South Africa, highlighting the composition of the online voluntourism domain. This in itself is valuable for ascertaining the local online presence of an emerging and important theme in the South African economic context. Unlike previous research in the field of tourism, furthermore, this study questions the use of geographical keywords to find relevant information about voluntourism experiences with respect to the use of specific activities-related keywords. We hypothesise that this is due to the purpose of the research undertaken, and ultimately to the purpose and motivation of the actual travel. Likewise, we expected to find a vast number of social media websites discussing actual tourism experiences (as highlighted in previous research in the field). In our study, the voluntourism online domain presents a relatively small number of social media websites and the touristic experience is barely mentioned: what is crucial in these analysed results is the social experience.

On a practical level, this research helps to ground the relevance of the topic for South Africa: the national tourism board is very much present within the search results and is actively disseminating information about responsible travel and volunteering within the country. There is a clear interest by the national tourism board in attracting volunteers and helping them in having meaningful experiences. This research can support such interests, sharpen the online promotion of meaningful experiences, and build toward more inclusive and engaging volunteer-touristic practices. Currently, users and potential volunteer-tourists are restricted to static and informative content, two-thirds of which is not even exclusively devoted to voluntourism. This reflects the fragmented nature of the industry. Future research may deepen this line of inquiry by focusing on the social perimeters of voluntourism in the online search domain, especially in the context of economically developing countries.

References

- Adorno, TW, 1991. The culture industry: Selected essays on mass culture. Routledge, London.

- Alexander, Z, 2012. The international volunteer experience in South Africa: An investigation into the impact on the tourist. PhD thesis, Brunel University.

- Baggio, R, Corigliano, AM & Tallinucci, V, 2007. The websites of a tourism destination: A network analysis. In Sigala, M, Mich, L & Murphy, J (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism. Wien, Springer, pp. 279–88.

- Bakker, M & Lamoureux, KM, 2008. Volunteer tourism-international. Travel & Tourism Analyst (16), 1–47.

- Bilbao-Osorio, B, Dutta, S & Lanvin, B, 2013. The networked readiness index 2013: Benchmarking ICT uptake and support for growth and jobs in a hyperconnected world. Geneva, World Economic Forum.

- Blackshaw, P, 2006. The consumer-controlled surveillance culture. http://tinyurl.com/k7r9flv Accessed 6 May 2014.

- Blackshaw, P & Nazzaro, M, 2006. Consumer-generated media (CGM) 101: Word-of-mouth in the age of the web-fortified consumer. Nielsen BuzzMetrics, New York.

- Brown, S & Morrison, A, 2003. Expanding volunteer vacation participation: An exploratory study on the mini-mission concept. Tourism Recreation Research 28(3), 73–82. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2003.11081419

- Buhalis, D & Law, R, 2008. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet – The state of eTourism research. Tourism management 29(4), 609–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

- Butcher, J, 2011. Volunteer tourism may not be as good as it seems. Tourism Recreation Research 36(1), 75–76. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2011.11081662

- Callanan, M & Thomas, S, 2005. Volunteer tourism: Deconstructing volunteer activities within a dynamic environment. In Novelli, M (Ed.), Niche tourism: Contemporary issues, trends and cases. Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 183–200.

- Cheong, CS, 2008. Sustainable tourism and indigenous communities: The case of Amantaní and Taquile Islands. Thesis in Historic Preservation. University of Pennsylvania.

- Cilibrasi, RL & Vitanyi, PMB, 2007. The Google similarity distance. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 19(3), 370–83. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2007.48

- Clifton, J & Benson, A, 2006. Planning for sustainable ecotourism: The case for research ecotourism in developing country destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 14(3), 238–54. doi: 10.1080/09669580608669057

- Comaroff, JL & Comaroff, J, 2009. Ethnicity, Inc. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

- Daldeniz, B & Hampton, MP, 2010. Charity-based voluntourism versus ‘lifestyle’ voluntourism: Evidence from Nicaragua and Malaysia. Kent Business School Working Paper No. 211. University of Kent.

- Daley, C, 2013. Voluntourism: An organisation in search of an identity. Major Research Paper, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs. University of Ottawa.

- Deller, S, 2010. Rural poverty, tourism and spatial heterogeneity. Annals of Tourism Research 37(1), 180–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2009.09.001

- Fleiss, JL, 1971. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin 76(5), 378–82. doi: 10.1037/h0031619

- Gretzel, U, 2006. Consumer generated content – Trends and implications for branding. e-Review of Tourism Research 4(3), 9–11.

- Gretzel, U & Yoo, KH, 2008. Use and impact of online travel reviews. In O'Connor, P, Höpken, W & Gretzel, U (Eds.), Proceedings of information and communication technologies in tourism. Vienna, Springer, pp. 35–46.

- Guttentag, DA, 2009. The possible negative impacts of volunteer tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research 11(6), 537–51. doi: 10.1002/jtr.727

- Guttentag, DA, 2011. Volunteer tourism: As good as it seems? Tourism Recreation Research 36(1), 69–74. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2011.11081661

- Hecht, B, Teevan, J, Morris, MR & Liebling, DJ, 2012. SearchBuddies: Bringing search engines into the conversation, pp. 138–145. Presented at the ICWSM, 2012.

- Herrero, Á & San Martín, H, 2012. Developing and testing a global model to explain the adoption of websites by users in rural tourism accommodations. International Journal of Hospitality Management 31(4), 1178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.02.005

- Inversini, A, 2011. Cultural destinatinations’ online communication and promotion. Lap Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbrücken, DE.

- Inversini, A & Buhalis, D, 2009. Information convergence in the long tail: The case of tourism destination information. In Höpken, W, Gretzel, U & Law, R (Eds.), Proceedings of information and communication technologies in tourism. Vienna, Springer, pp. 381–92.

- Inversini, A & Cantoni, L, 2011. Towards online content classification in understanding tourism destinations’ information competition and reputation. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising 6(3), 282–99. doi: 10.1504/IJIMA.2011.038240

- Inversini, A Cantoni, L & Buhalis, D, 2009. Destinations’ information competition and web reputation. Information technology & tourism 11(3), 221–34. doi: 10.3727/109830509X12596187863991

- iProspect, 2006. iProspect search engine user behaviour study. http://tinyurl.com/kmlgp6o. Accessed 15 July 2014.

- Jang, SC, 2004. The past, present, and future research of online information search. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 17(2/3), 41–47. doi: 10.1300/J073v17n02_04

- Jansen, BJ & Molina, PR, 2006. The effectiveness of Web search engines for retrieving relevant ecommerce links. Information Processing & Management 42(4), 1075–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2005.09.003

- Jansen, BJ, Booth, DL & Spink, A, 2008. Determining the informational, navigational, and transactional intent of Web queries. Information Processing & Management 44(3), 1251–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2007.07.015

- Krippendorf, J, 1987. The holiday makers. Heinemann, London.

- Lacey, G, Peel, V & Weiler, B, 2012. Disseminating the Voice of the Other: A Case Study of Philanthropic Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 39(2), 1199–220. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.01.004

- Li, C, 2010. Open leadership: How social technology can transform the way you lead. John Wiley & Sons, San Francisco.

- Lupoli, CA, Morse, WC, Bailey, C & Schelhas, J, 2014. Assessing the impacts of international volunteer tourism in host communities: a new approach to organizing and prioritizing indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22(6), 898–921. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.879310

- Lyons, KD & Wearing, S, 2008. Volunteer tourism as alternative tourism: Journeys beyond otherness. In Lyons, K. & Wearing, S. (Eds.), Journeys of discovery in volunteer tourism: International case study perspectives. CABI, Cambridge, pp. 3–11.

- McGehee, NG, 2002. Alternative tourism and social movement participation. Annals of Tourism Research 29(1), 124–43. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00027-5

- McGehee, NG & Andereck, K, 2009. Volunteer tourism and the ‘voluntoured’: the case of Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17(1), 39–51. doi: 10.1080/09669580802159693

- McGehee, NG & Santos, C, 2005. Social change, discourse and volunteer tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 32(3), 760–79. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.12.002

- Mostafanezhad, M & Kontogeorgopoulos, N, 2014. Volunteer tourism policy in Thailand. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 6(3), 264–67. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2014.890270

- Net Market Share, 2014. Market share statistics for internet technologies. Google – Global Market Share on Desktop. http://tinyurl.com/mgz3zpw. Accessed 6 May 2014.

- Nyahunzvi, DK, 2013. Come and make a real difference: Online marketing of the volunteering experience to Zimbabwe. Tourism Management Perspectives, 7, 83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2013.04.004

- Pan, B & Fesenmaier, DR, 2006. Online information search: Vacation planning process. Annals of Tourism Research 33(3), 809–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.03.006

- Pan, B, MacLaurin, T & Crotts, JC, 2007. Travel blogs and the implications for destination marketing. Journal of Travel Research 46(1), 35–45. doi: 10.1177/0047287507302378

- Parnaby, A, 2008. The cultural economy of survival: The Mi'kmaq of cape Breton in the mid-19th century. Labour/Le Travail 61, 1–33. Canadian Committee on Labour History.

- Pastran, SH, 2014. Volunteer tourism: A postcolonial approach. USURJ: University of Saskatchewan Undergraduate Research Journal 1(1), 45–57.

- Pratt, AC. 2007. The state of the cultural economy: The rise of the cultural economy and the challenges to cultural policy making. Urgency of Theory: 166–190. Carcanet Press/Gulbenkin Foundation, Manchester.

- Raymond, EM, 2011. Volunteer tourism: Looking forward. Tourism Recreation Research 36(1), 77–9. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2011.11081663

- Riffe, D, Lacy, S & Fico, F, 1998. Analyzing media messages: Quantitative content analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, New Jersey.

- Sim, J & Wright, CC, 2005. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: Use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Physical Therapy 85(3), 206–82.

- Sin, HL, 2010. Who are we responsible to? Locals’ tales of volunteer tourism. Geoforum 41(6), 983–92. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.08.007

- Sireyjol, D, 2010. Tourism in developing countries: A neglected lever of growth despite its potential. Private Sector Development 8, 25–27.

- Smith, VL & Font, X, 2014. Volunteer tourism, greenwashing and understanding responsible marketing using market signalling theory. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22(6), 942–63. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.871021

- SADT (South African Department of Tourism). 2012. Responsible tourism. http://www.tourism.gov.za Accessed 24 April 2014.

- Stoddart, H & Rogerson, CM, 2004. Volunteer tourism: The case of habitat for humanity South Africa. Geo Journal 60(3), 311–8.

- Taplin, J, Dredge, D & Scherrer, P, 2014. Monitoring and evaluating volunteer tourism: A review and analytical framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22(6), 874–97. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.871022

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), 2013. Human development report 2013. The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2013-report Accessed 2 May 2014

- Unwin, T, 2009. ICT4D: Information and communication technology for development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Wang, Y & Pfister, RE, 2008. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism and perceived personal benefits in a rural community. Journal of Travel Research 47(1), 84–93. doi: 10.1177/0047287507312402

- Wearing, 2001. Volunteer tourism: Experiences that make a difference. Cabi, New York. https://books.google.co.za/books?id=6VRrdFoCCDwC&dq=Volunteer+tourism:+Experiences+that+make+a+difference&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s Accessed 17 December 2014.

- Wearing, S & McGehee, NG, 2013. Volunteer tourism: A review. Tourism Management, 38, 120–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.03.002

- Xiang, Z & Gretzel, U, 2010. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism management 31(2), 179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

- Xiang, Z, Wöber, K & Fesenmaier, DR, 2008. Representation of the online tourism domain in search engines. Journal of Travel Research 47(2), 137–50. doi: 10.1177/0047287508321193