Abstract

This research investigated the impact of the establishment of a new university on hosting cities by reviewing the literature on such impacts. The aim of the article is to establish the likely impact of a new university (Sol Plaatjie University) to be established in the city of Kimberley during 2014. The study found that generally a university could impact its hosting city in terms of its local economy, employment, human capital, social character and real-estate market. Given the current characteristics and demographic profile of Kimberley, it is likely that positive impacts of a new university in Kimberley would include increased spending capacity in the local economy and short-term employment gains during construction of the university infrastructure. The proposed university could, however, exacerbate the existing pressure on the rental market in Kimberley and encourage the out-migration of specific skilled professionals. The research concludes with a number of steps to be taken by a hosting city that could contribute to strengthening a university's role as an anchor for urban development.

1. Introduction

There is a general consensus that institutions of higher education make a valuable cultural contribution to society. Higher education institutions are increasingly seen as ‘anchors’ for urban development that can serve as an important dimension of domestic change: ‘Anchor institution implies educational institutions that, by reason of mission, invested capital, or relationships to customers or employees, are geographically tied to a certain location’ (Perry & Menendez, Citation2011:4). Whilst the primary mission of these institutions is education and research, they perform much broader functions and can contribute towards the general well-being of an area. The impact of a new university on a city's population could be influenced by the projected influx of an educated workforce and the demand of an increased population for goods and services in an area. A new student population is likely to have positive spill-over effects that could stimulate a range of activities and improve a city's infrastructure, as well as influence the housing market (Powell & Barke, Citation2008). A number of studies have shown that the presence of a university could contribute significantly towards the local economy of a city. Similarly, an educated workforce contributes towards industrial diversification (see Weller, Citation1998; Fulton et al., Citation2003; Snowball & Antrobus, Citation2005; Carroll & Smith, Citation2006; Siegfried et al, Citation2006; Harvard University, Citation2009; Hoffman & Hill, Citation2009; Pastor et al., Citation2013; Sen, Citation2011).

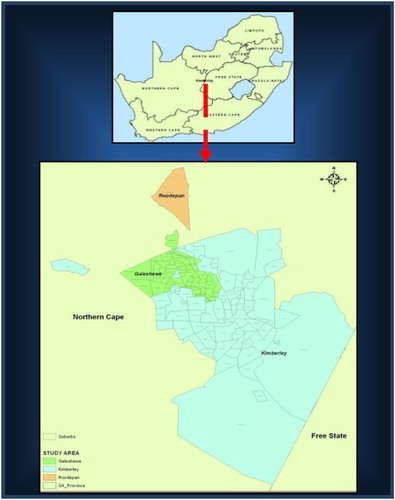

In South Africa, Mpumalanga and the Northern Cape are the only two provinces that presently do not have mature, long-established universities (). There are two universities planned for these two provinces as part of the government's infrastructure spending plan announced during the Minister of Finance Budget Speech of 2012, and one of them, Sol Plaatjie University, is to be constructed in the city of Kimberley in the Northern Cape. Both institutions will be opened during the course of 2014 and will accommodate approximately 5000 students in the Northern Cape over the long term. The aim of this study is to determine likely impacts of the new Sol Plaatjie University in the city of Kimberley, Northern Cape, by reviewing literature on the impact of universities on their hosting cities elsewhere in the world.

Figure 1: Distribution of the number of South African universities per province

2. Methodology and study area

This study used a theoretical approach to formulate a hypothesis on the impacts of the new Sol Plaatjie University on the city of Kimberley, by conducting a literature review of relevant studies pertaining to the impact of new universities on hosting cities elsewhere in the world. Case studies are used to present a position on these possible impacts.

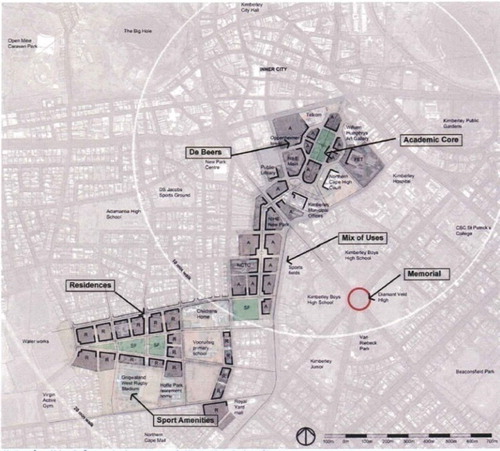

The geographic focus of the study is the city of Kimberley, on the eastern side of the Northern Cape Province, South Africa (); and for the purpose of this study, the geographic area for KimberleyFootnote3 is defined according to the 2011 Census place-name boundaries, and gives a population of 230 345 (South Africa, Citation2011). The proposed layout of the new university can be seen in .

3. Possible fields of impact from the literature

The urban role of the university campus has been increasingly outlined by many. Research by Hahn et al. (Citation2003) described a number of ways in which universities can serve as economic anchors in urban and rural communities. In the research named above, a university is seen as a purchaser of goods and services in a local area, as an employer, as a workforce developer in terms of implementing workforce training programmes with local and regional businesses, as a real-estate developer (a role that could potentially be pivotal in neighbourhood revitalisation), as an incubator of local knowledge-based economies by using the university's research capacity and, finally, as advisor and network builder. With this view as a basis together with research from authors such as Steinacker (Citation2005), Cortes (Citation2004) and Magdaniel (Citation2013), this paper suggests a number of potential fields of impact on a hosting city, each of which will be elaborated upon in this section. These fields of impact are: an economic impact; an employment impact; a human capital impact; a social impact; and a real-estate impact. Much of the research that has been done on university impacts on hosting communities derives mainly from developed countries, such as the United States and Europe, with only a few studies in developing countries such as Tanzania (Bailey et al., Citation2011). Institutions such as Harvard, Stanford, and MIT in the United States and Oxford and Cambridge in the United Kingdom are famous examples that have transformed the hosting cities of these higher education institutions.

3.1 Economic impact

Every college and university serves to some extent as an economic ‘anchor’ in its respective community. They create jobs, many offer training and education for local residents, and most support local businesses through the procurement of goods and services; some advance community development through real-estate projects; others facilitate community service projects that have an economic component; and nearly all partner with government and civic groups to strengthen the economic health of the community (Hahn et al., Citation2003). Universities can be valuable contributors to a city's economy. They are immobile institutions fairly resistant to business cycle fluctuations, making them a steady presence in a community. They tend to attract revenue from outside the immediate area through tuition, endowment income or state tax allocations and to attract significant human capital – students and employees from a national market – that can contribute to the area's economic growth.

According to Swinney (Citation2011), the main impact of a university on its city economy is through the attraction of students as consumers and later through their employment in a city economy.

Several university impact studies, which included construction of the university in their analysis, have indicated a significant contribution to the area's economy; for example, Arizona State University (Hoffman & Hill, Citation2009), Stanford University (Citation2008), University of Notre Dame (Citation2002) and Eastern Cape University (South Africa, Citation2009).

Spending by university students is one of the major sources of economic impact in an area surrounding a university. According to Princeton University (Citation2008:8), ‘the impact of student spending is determined in part by whether students live on campus, in off-campus university housing, or elsewhere in the university town'. Goods and services generally associated with student spending could include rented accommodation (by those not residing on campus), transportation, books and stationery, retail, banking, amusement and recreation, maintenance, and so forth. Estimates of student spending consider only those expenses incurred by students from outside the area of study, implying an injection of new money into the area. This is based on the assumption that local students would have spent their money in the area anyway, regardless of the presence of a university. Wilson & Raymond (Citation1973) argued that each time a student spends money in a community, employment is generated. The more students the university enrols, the more student spending takes place – and this will stimulate other parts of the economy in the area. While it is very difficult to attach statistics to the spending patterns of students at a new university, research has shown that some general trends do exist.

Regarding spending in the city of Prince George, where University of Northern British Columbia is located, it was found at first that much of the expenditure on goods and services occurred outside the region, due to a restricted local economy and a relatively small community. It has since become one of the largest employers in the region and has begun to maximise its use of human and physical resources to the benefit of the region (Weller, Citation1998).

In a South African study, the economic impact of four universities was examined. The economic impact of Rhodes University, for example, was quantified according to capital and operational expenditure, student spending and its research, technology transfer and innovation-related activities. Rhodes University is one of the smallest universities in the Eastern Cape Province with a student population of 6327 in 2008. The capital investments of the university resulted in an increased demand for goods and services (R14 million in 2008) and 30 new employment opportunities in the same year. Operational investments amounting to R665 million contributed to additional goods and services and R149 million towards gross domestic product. Most of the students come from outside the region and from outside the country. Student spending is generally on food, rent, entertainment, clothing, and so forth, which in 2008 created a demand for new goods and services of above R504 million along with 1041 additional employment opportunities in the area. Total demand for new products and services therefore amounted to R2 billion and approximately R400 million in GDP with almost 5000 new employment opportunities. Rhodes University has a high postgraduate enrolment underlining its focus on research. Consequently, funding for its research support amounted to R112 million during 2007. More than half of the research is conducted in the Eastern Cape Province (58%), Western Cape (14%) and Gauteng (10%). Therefore, it is evident that Rhodes University makes an important economic impact to the economy of the city of Grahamstown and the Eastern Cape Province as a whole.

In the impact study of Rhodes University in the Grahamstown area, Snowball & Antrobus (Citation2005) cited expenditure that was both derived from earnings in the Grahamstown area and new monies injected into the region. A random sample of 164 students covering national and international students was used for the study, who were interviewed using a questionnaire to obtain demographic and economic data. The average economic impact of student spending according to this study was approximately R38 000 for national students and about R40 000 per year for foreign students (per capita). This expenditure of South African students reflects similarly another survey, which found that the total spending of students at five different universities was estimated at approximately R39 000 per annum or about R3000 per month (Humphries, Citation2012). Tzoneva (Citation2010) in collaboration with UNISA also undertook a study that revealed how students spent their money, and reported that students spent most of their money on food (R652), rent (R501), clothes (R320), entertainment (R199), cosmetics (R153) and airtime (R152).

In a 2009 study conducted by the department of science and technology, the impact of student expenditure at Rhodes University has been shown to be significant. A total student enrolment of approximately 6300 created a demand for new goods and services of more than R500 million and generated an additional 1000 employment opportunities in the regional economy. By contrast, the impact of the University of Fort Hare's approximately 9000 students was calculated to be lower than the smaller student body of Rhodes University. This was mainly due to the differences in the demographic profile of the two universities’ students; students at the University of Fort Hare have less income to spend than those at Rhodes University – which adds something of a caveat to measuring the economic impact of student spending based only upon enrolment figures.

These studies strongly suggest that student spending can make an appreciable contribution to the city's local economy which depends largely on the spending power of students, as suggested by the Eastern Cape study (South Africa, Citation2009).

3.2 Employment impact

Universities constantly rank among the top employers in metropolitan areas, and are amongst the largest and most permanent land and building owners. This has come to be viewed by many as a driver of overall urban development.

Universities create both direct and indirect employment. Direct employment comes through the university itself, such as staff, faculty and administration, and additional employment through the operations of the university. Indirect and ‘induced employment impact’ refers to those regional jobs created by the university's economic impact; for example, city services (police, fire, nursing) and those in catering and the hospitality industry (hotels and restaurants, etc.). In their study on the effects of universities on the local labour market using Census data, Beeson & Montgomery (Citation1993) found only a marginal impact on the labour market. The demand for workers with specific skills was determined by the characteristics of the university; for example, science and engineering skills – skills that could assist companies in the area to implement new technologies. A recurring finding in all of the university impact studies is that institutions of higher education create additional employment particularly in the service sector. Moreover, Pastor et al. (Citation2013) noted that improvements in human capital contribute to lower unemployment rates in a region with the presence of a university.

Creating employment opportunities is an important strategy to prevent an exodus of skilled graduates from an area. Russo et al. (Citation2003) outlined two reasons why higher educational institutions fail to retain graduates in the city: the low profile of the employment market for various professions, and the incapacity of the city to offer challenging conditions to young graduates as far as housing and quality of life are concerned.

shows four South African Universities in the Eastern Cape Province and the additional employment created in the region. The general trend for the four universities shows an increase in the number of additional employment created from 2006 to 2008. Each university would create a magnitude of additional employment based on capacity and area characteristics; for example, Rhodes University is located in Grahamstown with a population of approximately 54 000 people, while Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University is located in a metropolitan area with a population of approximately 1 million (South Africa, Citation2011).

3.3 Human capital impact

Felsenstein (Citation1995) argued that migrants’ income generation and spending power provide a considerable financial injection into the local economy in the short term. Over a longer period, such migratory effects of a pool of highly skilled workers increase the attractiveness of a region and reverse the negative migration trends, particularly in small towns and rural locations. Aidis et al. (Citation2005) argued that students who graduate with specialist degrees such as economics, science and informatics have a higher tendency to migrate because they are in a greater demand.

The relative importance of human capital and expenditure effects depends on the size of the economy where the university is located. In a small economy, typically rural area some distance from a major metropolis, students specifically move to the area to attend college, bringing new dollars with them, but they do not stay after graduation. There is little long-term increase in local human capital, but the short-term influx of student expenditures can be significant in such an isolated economy (Steinacker Citation2005:1162). The study by Steinacker (Citation2005) also found that with direct incorporation of student expenditure effects, both residential and commuter, it is clear that even small campuses can play a very strong economic role in their home towns.

Weller (Citation1998) analysed the impact of the University of Northern British Columbia on a developing region during its first year of operation. The University of Northern British Columbia had an immediate effect on enhancing human capital in the region by improving the local participation rate, creating more educational opportunities for regional residents, which increased its economic attractiveness and drew skilled people and businesses to the area. Most of the students and staff came from outside the region – this had a significant influence, as new skills were introduced that were not there previously; without the university, these skills would never have been brought to the area. Weller highlights the need for local residents to change their thinking about the more permanent and stable infrastructure introduced to the region thanks to the new university

3.4 Social impact

Higher education is relentlessly challenged to change and align its roles to respond proactively to the needs of students, communities and society as a whole (Hahn et al., Citation2003).

One characteristic of a university town is that it consists of a large percentage of student population that is attending one or more colleges and universities, as well as the academic and support staff of those institutions. Typically, this population would be highly educated, transient in nature (present for the school year(s) and the term of their education) and also young (probably in their twenties). Demographically, the proportion of female students has increased dramatically, and there is growing demand from students who are older than the traditional college age and who are tied to a geographic location (Hashimshony & Haina, Citation2006).

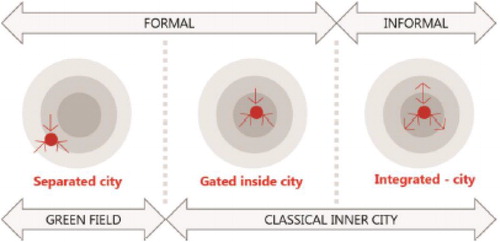

Den Heijer in Magdaniel (Citation2013), in her study of a Dutch university campus, addresses three types of campus settlements: a campus as a separate city; a campus as a gated community in the city; and a campus integrated with the city. The overall three views on campus and their relationship with the city are illustrated in . In each of these circumstances the multiple functions allocated on campus can be perceived as either threats or benefits for the immediate surroundings. For instance, in terms of liveliness the mix of functions and infrastructure might be considered as benefits for the city (Magdaniel, Citation2013). The provision of these services contribute to the quality of life and hence the attractiveness of the city as a working and living location for business and workers. The need for expansion can be seen as a threat of displacement for renters and low-income households in surrounding neighbourhoods, especially in inner-city campuses.

The difference in time schedules between students’ communities and the organisation of the city's activity could result in increasing opportunities for residents but also in provoking a rupture in their social routines. For example, a badly managed mixed use of public space may create a ‘cultural shock’ which gives the university a bad reputation and hinders its role as an engine of local development.

Furthermore, different phases of a new university cause different migration streams; for example, during the building phase of a university, construction workers are brought to the area for a short duration and their economic impact is different to other migrants, such as university staff, who will stay in the area. Students in particular could be classified under the short-term effects of migration (temporary migration), with the exception of those who remain in the area after they have graduated. In this regard, their economic impact would be more significant than those who leave the area after completing their studies.

In some instances, as noted by Rugg et al. (Citation2000), the intensive concentration of students in an area has resulted in conflict with local residents. Sabri & Ludin (Citation2009) described the phenomenon of studentification as the process generated by a residential concentration of higher education students, affecting the composition of an area, bringing about social, environmental and economic change. However, high concentrations of students are generally depicted as having strongly negative consequences for neighbourhoods (see Munro et al., Citation2009; Sage et al., Citation2012). Problems are created by conflicts between student lifestyles and those of other residents. High concentrations also mean that what might otherwise be relatively minor annoyances (such as late-night noise) come to be dominant features of neighbourhoods.

Kenyon (Citation1997) argued that as the student population increases, it also changes the demographic profile of an area, since students themselves establish households. These newly created student households have different needs to a family household. Private local residents generally perceive their environment and surroundings to be a private space that they control, and somewhere they can feel secure. Anything that disturbs these indicators would create unease amongst residents and may lead to confrontation. Kenyon (Citation1997) argued that satisfaction with one's neighbour and levels of ‘neighbouring’ are significant predictors of neighbourhood satisfaction. The student population, a highly transient group that changes tenancy once a year and is also absent for extended periods throughout the year, could therefore significantly undermine such a ‘safe and sound’ environment.

The vacation breaks during the year allow residential properties to stand vacant for extended periods, possibly attracting criminals to the area. Therefore, local residents would find it very difficult to remain in such areas where the environment is not conducive to social interaction. Students on the other hand, according to Kenyon (Citation1997), might find it difficult to identify with local residents due to the age gap and the general differences in lifestyles.

To improve relations, the study suggests that students get involved in local neighbourhood activities, such as neighbourhood watches and associations, to harmonise interests and needs. From a university's perspective, the institution could intensify its public relations strategy to address any fears that a surrounding community might have.

3.5 Real-estate impact

According to a report by the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation (Citation2007), the presence of universities impacts the neighbourhood housing market in several ways. Firstly, students tend to stay together with roommates and thus can afford to pay a higher rental price by pooling resources. This often pushes the property price beyond the reach of non-academic residents (families and single occupants), and in certain instances residents are forced out of the area due to escalating rental prices (see Levin & Abend, Citation1970; Fox, Citation2008). Secondly, studies have shown that students and university staff alike would prefer to stay within close proximity of the university to reduce travelling time and avoid potential congestion. As Aksugur & Onal (Citation1997:3) correctly pointed out, ‘universities will exert within their region a strong attractive power and become preferred places around which to live'. Potentially, this allows landlords to increase their rental prices beyond affordable market rates for the neighbourhood, creating a strictly student area. A third way in which rental prices are increased is due to the effects of supply and demand; increased demand tends to influence the rental price of housing stock.

Rugg et al. (Citation2000) and Powell & Barke (Citation2008) presented a detailed analysis of the relationship between the student population and house prices in Newcastle upon Tyne in the United Kingdom. The authors indicated that with the introduction of students to the town there tended to be a general increase in property prices over the long term until a certain saturation level had been reached – but they found that this relationship between students and property prices is inconsistent. Powell & Barke (Citation2008) analysed the relationship between students and property prices in three areas in the city of Newcastle. The United Kingdom has experienced rapid student enrolment with the government's drive for increased participation in higher education, which has resulted in increased demand for student accommodation. A marked feature was the creation of ‘student areas’, formed by students with a desire to stay in close proximity to other students and associated facilities, such as retail and recreational services, causing a concentration of students in a given area. From 2000 until 2006 the student population in Newcastle grew by more than 40%, placing a huge demand on student accommodation, resulting in students turning to the private market. The relationship between students and house prices was thus found to be inconsistent, and the rate of change and development in an area is an important consideration in this regard.

4. Implications for Kimberley

As with all other higher educational institutions, the new university in Kimberley will draw students and staff from areas outside the hosting city, due mainly to the city's limited capacity to cater for the university. According to South Africa (Citation2012), Sol Plaatjie University will, during its first year in 2014, have limited enrolments (approximately 140 students) and limited academic programmes such as Education, Information Technology, and Retail Business Management. It is expected that over the next 10 years the number of student enrolments will grow to approximately 5000 with an expanded academic programme. In terms of the suggested impacts derived from the literature and case studies above, this paper suggests the following as possible areas of impact for Kimberley that could form the basis for future research.

4.1 Economic and employment impact

The increase in student numbers will have a positive impact on the local economy of Kimberley through the spending of students; however, the size of the impact would largely depend on the spending power of students. Furthermore, student spending could assist in diversifying the economic platform of the area, bringing in industries that previously were not present in the Kimberley region; for example, suppliers of laboratory apparatus, computers, printer and copier maintenance and stationery requirements on a previously unknown scale. Since a large part of the focus of the new university in Kimberley is on science and technology, associated employment opportunities in these fields would have to be created to avoid a youth ‘brain drain’.

The establishment of the new university in the city of Kimberley will involve the construction of new buildings, as the current infrastructure is insufficient to meet the needs of the new campus. The construction of the university during the period 2013–2018 constitutes approximately 57% of the budget, amounting to about R2.6 billion (South Africa, Citation2012). The total operational and capital budget for the same period amounts to approximately R4.5 billion (). The construction phase of the university is likely to impact positively on the local community and businesses, as some building materials are purchased locally and contract workers are employed from the local area, even though some will come from outside the Kimberley region. Studies revealed that as much as 80% of the local people could be used for the construction phase. Moreover, workers that are employed from other towns spend their income on local goods and services (e.g. food, entertainment, and accommodation), and thus contribute to the economy of the city.

Table 1: Preliminary budget and cash flow for the Sol Plaatjie University (South Africa, Citation2012)

It is anticipated that student spending will probably have a positive impact on the local economy in the city of Kimberley and that this contribution, however, will be experienced gradually as the university increase its recruitment to approximately 7500 students over the next 10-year period. Students at the Sol Plaatjie University could typically spend money on items such as accommodation, food, clothing, books and entertainment as research has shown in other South African universities (Tzoneva, Citation2010). The amount of student spending would result in improved returns in these related industries and a positive contribution to the local economy of Kimberley.

4.2 Real-estate impact

The new university is expected to accommodate approximately 5000 students (South Africa, Citation2012), making it one of the lowest enrolment figures compared with other higher educational institutions in South Africa (). According to the SA Commercial Property News (Citation2012), South Africa's higher educational institutions are currently experiencing a critical shortage of student accommodation. The national government's target is to increase the university participation rate of the population to 20% by 2016. This target translates into increased enrolments at current educational institutions, which will put pressure on supporting infrastructure to accommodate the increased number of students. The department of higher eduction and training identified the lack of student accommodation as one of the key contributors to poor student performance and high drop-out rates at some of the universities (South African Press Association, Citation2012). Furthermore, those students who do manage to secure accommodation are often left to live in appalling conditions, especially those coming from rural areas and poor backgrounds (South Africa, Citation2012). According to South Africa (Citation2012), approximately 80% of the student population of the new university in the Northern Cape will be housed in student residences, and it is therefore assumed that some students would also be accommodated in the private rental market as well – although this naturally excludes locally resident Kimberley students.

Table 2: Number of student enrolments at South African tertiary institutions

The cause of the accommodation shortage is that supply has not grown in parallel with the increase in student numbers in South Africa (South Africa, Citation2012). The department of higher education and training reported that at a national level only about 100 000 of the approximately 530 000 enrolled student population is currently accommodated by universities. The increased demand for student accommodation could therefore influence the property market significantly in certain areas, as shown by various university impact studies. Large cities or metropolitan areas with a significant amount of housing stock could potentially cope well with increasing numbers of students, but for smaller cities, where facilities are limited, this could pose a potential problem.

A shortage in student accommodation is likely to occur in Kimberley (Aida National Franchises, Citation2012). Furthermore, the local rental market is already under severe pressure to provide accommodation for the current demand in Kimberley. According to Roodt (Citation2012), in Grahamstown the cost of houses in the area has quadrupled since the early 1990s, mainly as a result of this increased demand and a lack of supply, owing to the slow release of land for private development.

4.3 Human capital impact

In a comparison between the town of Grahamstown and that of Kimberley due to the relatively similar population size of the town and the similarity in the enrolment numbers of the two institutions, characteristics of the post-school youth in Kimberley and Grahamstown revealed the role that the presence (and the absence) of a university have on the 18 to 24 years age group (). The figure shows that this age group in Grahamstown shows a significantly higher percentage of people attending a tertiary institution than those in Kimberley. The absence of a university is clearly evident in those that attend a university as well as educational attainment ().

Figure 6: Educational attainment for percentage persons aged 18 to 24 years old

Figure 7: Percentage of persons aged 18 to 24 years attending an educational institution

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the possible impacts of new universities on hosting cities by considering examples of such elsewhere in the world. Generally, positive impacts of a new university relate to increased spending in the local economy, a greater concentration of skills-based knowledge and short- and long-term employment gains. Negative impacts have been observed regarding social consequences of studentification of neighbourhoods, as well as pressure on local property and rental markets. The study suggests that the city of Kimberley could benefit positively from the population increase due to inward migration of mainly post-school youth. However, the research cautioned against studentification, which could have a potentially negative effect on the city as a result of the social behaviour of students, and could influence the property market with equally negative implications for Kimberley. The study also found that construction could make a significantly positive contribution to the city, especially in respect of short-term employment generation and capital investment. The literature encourages making use of local labour to improve direct employment in the area, and the spin-off effects of the university could lead to more indirect jobs in the area. The study could not, however, determine the impact of student spending because this factor is dependent on the particular spending power of students.

Sol Plaatjie University and the University of Mpumalanga would be the first universities to be built in the new democratic era, and many economic spin-offs are expected. It is important to recognise, however, that it may take up to a decade before the new universities are cost-effective and sustainable (South Africa, Citation2012). Furthermore, the construction and maintenance of a new university requires substantial human resources and it would be critical that local people be capacitated and employed to ensure the residents of Kimberley and neighbouring towns become part of such a significant development. Nevertheless, there is much eager anticipation for the first university in the Northern Cape, and several studies have shown that new universities make a positive contribution to a hosting city.

While making decisions on the university campus is a complex process that cannot ignore the context of which it forms an integral part, universities and cities are still developing their strategies separately, missing opportunities to share not only visions but also resources necessary to fulfil their shared ambitions in the knowledge economy (Magdaniel, Citation2013).

Research by Hahn et al. (Citation2003) presented a number of steps that could be employed by universities and colleges in order to strengthen the ‘anchor’ role in hosting cities’ urban development. These relate to the following:

Partnering with community-based organisations that are linked to local businesses or community institutions.

Incorporating job training and professional development programmes in employee programmes.

Engaging multiple university departments in advisory relationships in order to provide meaningful services to communities.

Creating explicit economic development goals.

Providing much-needed services for employees from neighbourhoods, such as childcare, transportation, and so forth.

Developing hiring policies that emphasise permanent positions instead of temporary arrangements or contract work.

Directing incubators and workforce programmes toward vulnerable populations and communities.

Participating in affordable housing or transportation development.

Although there could be a general expectation that the new university could address much of the socio-economic challenges facing the city of Kimberley and the Northern Cape, it is however cautioned by Weller (Citation1998) that a university should not be regarded as a cure-all for a city's problems, but rather as part of the overall development agenda of an area. Although it is anticipated that the university will bring about positive change and contribute considerably towards the Northern Cape, the expectation is that such changes and impacts will not happen overnight.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

3For the purpose of this study, Kimberley consists of the following Census 2011 main places: Kimberley, Galeshewe, and Roodepan

References

- Aida National Franchises, 2012. ‘Kimberley infrastructure problems put homebuyers out in the cold’. http://www.aida.co.za/admin_news_articles/news_article/336 Accessed 11 September 2012.

- Aidis, R, Krupickaité, D & Blinstrubaité, L, 2005. The loss of intellectual potential: Migration tendencies amongst university students in Lithuania. Annales Geographiae 41(2), 33–40.

- Aksugür, N & Önal, Ş, 1997. Accommodation problems in university hosting cities: A case in North Cyprus. Paper presented at the International Symposium of Culture and Space in Home Environment, New Paradigms, 1997, 4–7 June, ITU, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Allston Brighton, 2007. A status report on housing and the community. A report by the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation.

- Bailey, T, Cloete, N & Pillay, P, 2011. Universities and economic development in Africa. Case study: Tanzania and University of Dar es Salaam. Centre for Higher Education Transformation (CHET), Wynberg.

- Beeson, P & Montgomery, E, Nov 1993. The effects of colleges and universities on local labour markets. The Review of Economics and Statistics 75(4), 753–61. doi: 10.2307/2110036

- Carroll, MC & Smith, BW, 2006. Estimating the economic impact of universities: The case of Bowling Green State University. The Industrial Geographer 3(2), 1–12.

- Cortes, A, 2004. Estimating the impacts of urban universities on neighbourhood housing markets: An empirical analysis. Urban Affairs Review 39(2), 342–75. doi: 10.1177/1078087403255654

- Felsenstein, D, Aug. 1995. Dealing with “Induced migration” in university impact studies. Research in Higher Education 36(4), 457–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02207906

- Fox, M, 2008. Near-campus student housing and the growth of the town and gown movement in Canada. TownGownWorld E-Journal. January 2008.

- Fulton, GA, Grimes, DR & Sedo, SA, 2003. The economic impact of the University of Michigan on the State of Michigan. Institute of Labour and Industrial Relations. University of Michigan, Michigan.

- Hahn, A, Coonerty, C & Peaslee, L, 2003. Colleges and universities as economic anchors. Campus Compact: Providence.

- Harvard University, January 2009. Investing in innovation: Harvard University's impact on the economy of the Boston area. Harvard University: Office of Community Affairs, Boston.

- Hashimshony, R & Haina, J, 2006. Designing the university of the future. Planning for Higher Education 34(2), 5–19.

- Hoffman, D & Hill, K, May 2009. The contribution of universities to regional economies. A Report from the Productivity and Prosperity Project (P3).

- Humphries, F, 2012. Student spending is going up, but so are their savings! http://www.studentmarketing.co.za/blog-featured/student-spending-is-going-up-but-so-are-their-savings Accessed 21 October 2012.

- Kenyon, EL, Jun 1997. Seasonal sub-communities: The impact of student households on residential communities. The British Journal of Sociology 48(2), 286–301. doi: 10.2307/591753

- Levin, MR & Abend, NA, 1970. University impact on housing supply and rental levels in the city of Boston. Boston Urban Institute Occasional Papers.

- Magdaniel, FC, 2013. The university campus and its urban development in the context of the knowledge economy. www.eura2013.org Accessed on 2014-11-01.

- Munro, M, Turok, I & Livingston, M, 2009. Students in cities: A preliminary analysis of their patterns and effects. Environment and Planning A 41, 1805–25. doi: 10.1068/a41133

- Pastor, JM, Pérez, F & de Guevara, JF, 2013. Measuring the local economic impact of universities: An approach that considers uncertainty, Higher Education 65, 539–64.

- Perry, D & Menendez, C, 2011. The impact of institutions of higher education on urban and metropolitan areas: Assessment of the Coalition of Urban and Metropolitan Universities. Great Cities Institute, Champaign.

- Powell, K & Barke, M, 2008. The impact of students on local house prices: Newcastle upon Tyne, 2000–2005. Northern Economic Review 38(Spring 2008), 39–60.

- Princeton University, 2008. Education and Innovation. Enterprise and Engagement. The Impact of Princeton University.

- Roodt, JJ, 2012. Socio economic specialist report: Belmont valley and existing Grahamstown golf course development. Department of Sociology, Rhodes University.

- Rugg, J, Rhodes, D & Jones, A, 2000. The nature and impact of student demand on housing markets. Joseph Rountree Foundation 2000. York Publishers, Layerthorpe, York.

- Russo, A, van der Berg, L & Lavanga, M, 2003. The student city. Strategic planning for student communities in EU cities. European Institute for Comparative Urban Research (EURICUR), Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam.

- Sabri, S & Ludin, ANM, 2009. “Studentification” is it a key factor within the residential decision-making process in Kuala Lumpur? University of Technology, Kuala Lumpur.

- SA Commercial Property News, 2012. More on demand for student accommodation spikes in South Africa. http://www.sacommercialpropnews.co.za/property-types/housing-residential-property/4946-more-on-demand-for-student-accommodation-spikes-in-south-africa.html Accessed 12 October 2012.

- Sage, J, Smith, D & Hubbard, P, 2012. The rapidity of studentification and population change: There goes the (Student)hood. Population, Space and Place 18, 597–613. doi: 10.1002/psp.690

- Sen, A, 2011. Local income and employment impact of universities: The case of Izmir University of Economics. Journal of Applied Economics and Business Research 1, 25–42.

- Siegfried, JJ, Sanderson, AR & McHenry, P, 2006. The economic impact of colleges and universities. Working paper No 06-W12, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University.

- Snowball, JD & Antrobus, GG, 2005. The economic impact of Rhodes University students on the Grahamstown economy. The International Office, Rhodes University, Grahamstown.

- South Africa (Republic of), 2009. Regional economic impact assessment of Eastern Cape Universities. Department of Science and Technology. Cooperation Framework on Innovation Systems between Finland & South Africa (COFISA). Port Elizabeth.

- South Africa (Republic of), 2011. Census 2011 statistical release. P0301.4. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- South Africa (Republic of), July 2012. Development framework for new universities in the Northern Cape and Mpumalanga Provinces. Department of Higher Education and Training, Pretoria.

- South African Press Association (SAPA), 2012. ‘Universities for Mpumalanga and Northern Cape’. http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Universities-for-Mpumalanga-Northern-Cape-20120705 Accessed 6 July 2012.

- Stanford University, 2008. Economic impact study 2008 Published by Stanford University Office of Public Affairs. Summer 2008.

- Steinacker, A, 2005. The economic effect of urban colleges on their surrounding communities. Urban Studies 42(7), 1161–75. doi: 10.1080/00420980500121335

- Swinney, P, May 2011. Starter for ten: Five facts and five questions on the relationship between universities and city economies. Centre for Cities.

- Tzoneva, D, 2010. Student village reveals that SA students are ‘responsible’. http://www.marketingupdate.co.za/?IDStory=24995 Accessed 1 November 2012.

- University of Notre Dame, 2002. Notre Dame and the Local Economy: 2002. Economic Impact Report.

- Weller, GR, 1998. The impact of a new university in a developing region: The case of the University of Northern British Columbia. Higher Education Policy 11(1998), 281–90. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8733(98)00018-X

- Wilson, JH & Raymond, R, December 1973. The economic impact of a university upon the local community. The Annals of Regional Science 7(2), 130–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01283489