Abstract

International development projects that support entrepreneurship face a number of challenges, not least because they need to integrate different paradigms. Based on the case study of a Canadian non-governmental organisation in South Africa, this paper provides an exploratory assessment of these challenges and highlights four major factors that affect the success of such international projects: transposing a northern business model to the south; developing local roots and adapting to the local context; balancing the allocation of resources between managing the project and providing services to entrepreneurs; and aligning the cultures of the private sector and international development agencies. In practical terms, the findings provide benchmarks for the success of these projects and could help improve interventions that encourage entrepreneurship in developing countries.

1. Introduction

In line with the theoretical understanding that entrepreneurship can be a mechanism for development, some international agencies promote the creation of new businesses in developing countries. Such businesses benefit the governments of these countries, since they foster growth and job creation for the poorest people, which in turn promotes a better distribution of wealth (Bruton et al., Citation2008; Naudé et al., Citation2008; Abdullah et al., Citation2009; Azmat & Samaratunge, Citation2009; Latha & Murthy, Citation2009; Bhagavatula et al., Citation2010; McMullen, Citation2011; Naudé, Citation2011).

As noted by Naudé (Citation2010:39), entrepreneurship has long been absent from theories of economic development, and ‘the time has come for a closer integration of entrepreneurship and development economics’. However, the relationship between entrepreneurship and international development projects is complex, and more research is needed on the links between entrepreneurship, institutions and development, especially in Africa. Even if the importance of supporting entrepreneurship to foster economic development is recognised, the question of how to achieve it remains. A growing number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been established with the mandate to support entrepreneurs in developing countries (Ryfman, Citation2009), but these initiatives face various operational challenges. While a few exploratory studies have been carried out on particular programmes, measures or projects (Colletah, Citation2000; Della-Giusta & Phillips, Citation2006; Latha & Murthy, Citation2009), these were mainly descriptive. Additional studies are needed to identify emerging patterns and provide more detailed theoretical proposals.

International initiatives to support entrepreneurship have to integrate various different paradigms. For example, private-sector companies aim to generate profits while NGOs promote the development of people. There are also differences in the entrepreneurial culture between developed countries and developing or emerging ones (Tremblay et al., Citation2013). The literature on these topics appears limited. While the literature on projects done under public–private partnerships explores some of these differences (Chen et al., Citation2006), their findings do not readily apply to international projects on entrepreneurial development.

It is therefore still not clear which factors determine the success of international projects on entrepreneurial development. Such success should be measured in terms of both the management of the entrepreneurial development project and the businesses created by its clients (the entrepreneurs). Hence, measures of a project's success should include indicators of its own lifecycle and that of the projects undertaken by the entrepreneurs.

From this perspective, this article presents an exploratory study of the factors affecting the success of international projects for entrepreneurial development. The case study assesses the South African operations of the Canadian non-profit organisation Enablis, which supports entrepreneurship in developing countries in order to reduce poverty and promote sustainable development. The context of its operations is that the South African government has implemented a policy on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to create long-term employment and reduce the disparities between these enterprises and large companies (SEDA, Citation2009). From a globalisation perspective, its approach aims to maximise the benefits from international trade (Ras & Vermeulen, Citation2009).

This study provides neither a detailed review of all the economic factors that may influence entrepreneurial development nor recommendations for supporting the creation of businesses in a developing country. Rather, the study focuses on organisational support for entrepreneurs. The article first introduces the theory on the success of international development projects and support for entrepreneurial development, and then presents the conceptual model. The following section describes the methodological approach, while the results section presents the data analysis in terms of the main phases of the project lifecycle. Finally, the discussion section highlights four main challenges in creating an NGO that promotes entrepreneurship in developing countries; this raises issues for discussion to guide researchers and practitioners in this regard.

2. Theoretical approach

There appear to be few empirical studies on a model for assessing the benefits of international projects for entrepreneurial development. Most of the literature assesses the general factors that contribute to the success of such projects or of the resulting companies, the individual characteristics of the entrepreneurs, or entrepreneurship attributes (Naudé et al., Citation2008; Abdullah et al., Citation2009). These studies offer limited insight into the success of international projects to support entrepreneurs in developing countries.

2.1 Entrepreneurship in South Africa

Given its importance for economic development, both international organisations and national governments have made concerted efforts to promote entrepreneurship in developing countries, since they recognise the role of business creation in addressing poverty (Lingelbach et al., Citation2005). Since 1994 South Africa has implemented a number of initiatives to boost the economy, and particularly entrepreneurship. The post-apartheid government prioritised the development of SMEs through policies aimed at fostering entrepreneurship (Bradford, Citation2007). From 2000 to 2009, the number of registered businesses increased from 107 886 to over 255 383, and more than 63.6% of the new businesses were created by black people, who comprise 80% of the population (Preisendorfer et al., Citation2012). Several government institutions support entrepreneurial development, including the Small Enterprise Development Agency, the Small Enterprise Finance Agency, the National Empowerment Fund, the Industrial Development Corporation, the National Youth Development Agency, the Land Bank, and the Micro Agricultural Financial Institutions of South Africa (MAFISA). These institutions are supported by various NGOs, a number of which are initiatives from northern countries that support business creation in developing countries (Ryfman, Citation2009). But many of these programmes are strongly criticised by the recipients as well as by experts, for reasons such as bureaucracy, inefficiency, high interest rates and limited access (GEM, Citation2011).

2.2 Factors determining the success of international development projects

Given the complexity of international development projects, many studies have identified different dimensions related to their success. One dimension is whether the project achieved the anticipated outcomes and impact (Ika, Citation2007). Diallo & Thuillier (Citation2004) argue that it is difficult to determine the success of a project on the basis of its impact because a project can fail to have the desired impact even when it has been properly managed.

The design, management and implementation of projects in the community are important local success factors (Youker, Citation1999; Ika, Citation2012). Ambiguous planning, limited feedback, weak control mechanisms, inadequate risk assessment, bureaucratic management by the donors, and a lack of interaction between the donor and the organisation are all factors that may cause the project to fail. The project's sustainability is another dimension of success, which is often linked to stakeholder involvement and local capacity-building (Lim & Zain, Citation1999; Youker, Citation1999; Diallo & Thuillier, Citation2004; Khang & Moe, Citation2008; Hermano et al., Citation2013; Tremblay et al., Citation2013). Muriithi & Crawford (Citation2003) link the failure of projects to a lack of internal capacity and the difficulty that project beneficiaries face in managing the changes made by the projects, especially where these conflict with the local culture and traditions.

According to various studies (Ramaprasad & Prakash, Citation2003; Ika, Citation2007, Citation2012; Brière & Proulx, Citation2013), several international development projects have failed owing to the donor or initiators following a top-down approach and ignoring local knowledge. Some tried to impose an external or ‘ready-to-wear’ model that failed to account for the diversity of the environment (Ika, Citation2012). The success of development projects is highly dependent on the specific environment and the cultural diversity of the various actors, and leadership style and intercultural communication have a significant impact on the entire lifecycle of the project (Muriithi & Crawford, Citation2003; Anantatmula & Thomas, Citation2010; Ochieng & Price, Citation2010). Donors must thus ensure that the local community takes ownership of the project and understands the final results (Holcombe et al., Citation2004).

2.3 Support for the creation and survival of SMEs

Carrier & Tremblay (Citation2007) note that approaches to entrepreneurial support increasingly emphasise skills development (see also Bosman & Gerard, Citation2000). Many newly established SMEs fail because the entrepreneurs lack appropriate training (Latha & Murthy, Citation2009; Bloom et al., Citation2010; Bruhn et al., Citation2010). According to Gibb (Citation2005), entrepreneurial skills are not innate: an individual may be helped to develop these skills, usually through training and coaching (Ozgen & Minsky, Citation2007). While entrepreneurs from around the world do share certain characteristics and skills, many other aspects depend on the local culture (Ozgen & Minsky, Citation2007; Mano et al., Citation2012). Thus, efficient entrepreneurial support programmes must be culturally sensitive and properly analyse the needs of the entrepreneurs (Latha & Murthy, Citation2009).

A key issue in assessing entrepreneurial support programmes is evaluating their impact, but the literature on this is limited (Barès, Citation2004). The effectiveness of these programmes must be examined by measuring their impact on the creation of new SMEs, not just on the basis of indicators of the economic impact of their training (number of jobs created, revenues, etc.) (Mano et al., Citation2012). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recommends systematically including such quantitative indicators, as well as qualitative criteria such as the evolution of the local climate, involvement and learning (Tremblay, Citation2011).

2.4 Conceptual model

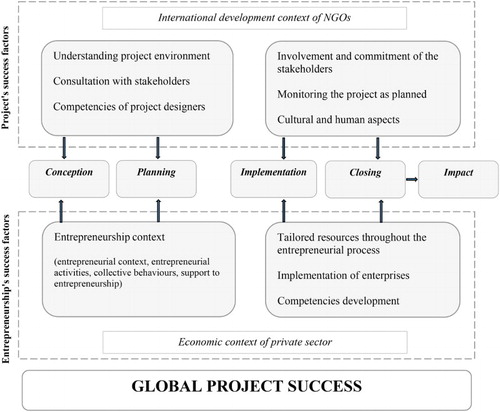

Since there is no applicable model on international projects for entrepreneurial development, this study draws on relevant studies to propose a model for analysis (see ). The model includes indicators to validate the results of international development projects (Khang & Moe, Citation2008), as well as indicators on entrepreneurship (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000; Steyart & Katz, Citation2004).

The model includes five main phases: conceptualisation, planning, implementation, closure and impact. The impact of the project is considered in terms of both the international development and the private-sector contexts, because these have distinctive characteristics (as outlined in the literature above). The model also takes into account both the environment of projects carried out by NGOs and the environment in which businesses are created.

3. Methodology

This exploratory conceptual framework was tested by means of the case study of Enablis, a Canadian NGO. Different data collection strategies were used to ensure data triangulation, including semi-directed interviews, focus groups, participant observation and documentation (Silverman, Citation2010). Data were mainly collected in South Africa (Cape Town and Johannesburg), where Enablis operates, and in Canada, where its top management as well as some partners and donors are located.

3.1 Description of the case study

Following the end of apartheid, the new South African government focused on strengthening the economy, in part by implementing policies to foster entrepreneurship (Bradford, Citation2007). As already noted, from 2000 to 2009 the number of registered businesses increased from 107 886 to over 255 383 (Preisendorfer et al., Citation2012). However, 24% of South African workers are still employed in the informal sector. Without this sector, unemployment in the country would have risen from 25% to 47% (Bradford, Citation2007). Recognising its legitimacy despite its illegality (Webb et al., Citation2009), the solution is not eradicating the informal sector, but rather is gradually regularising and formalising it by supporting the entrepreneurial potential of poor people (UN-Habitat, Citation2006). For instance, a simple, tax-free, legal form of enterprise should be put in place to allow informal businesses to register as legal entities (GEM, Citation2011).

Against this backdrop, several government institutions and NGOs were established to support formal entrepreneurial development in South Africa. This case study focuses on Enablis, a Canada-based non-profit organisation that supports entrepreneurs in the developing world through its member-driven network, called the Enablis Entrepreneurial Network. Created at the 2002 G8 Summit and founded by the Canada Fund for Africa, Accenture and Telesystem, this NGO obtained CAN$10 million in funding from the Canadian International Development Agency.

The Enablis approach differs significantly from that of microcredit programmes, such as Grameen, which make small loans to people traditionally excluded from financial services. Enablis uses a competitive process to select candidates who demonstrate high entrepreneurial potential, as it seeks to recruit ‘opportunity’ entrepreneurs with innovative ideas rather than ‘necessity’ entrepreneurs (Naudé, Citation2010). It provides networking, learning, mentoring and coaching services to assist them in achieving self-sufficiency. Since its establishment, Enablis projects are estimated to have assisted at least 1213 South African entrepreneurs (of whom 36% are women and 73% are black) and created 6040 new jobs (Bester, Citation2012).

3.2 Data collection and analysis

In line with the conceptual model, a questionnaire with open-ended questions was developed and a semi-directed interview process followed. Data collection took place between September 2011 and August 2012. A total of 33 respondents were interviewed, including members of the top management of Enablis, entrepreneurs, partners and donors, employees, researchers and local NGOs (see ). Once the interviews had been transcribed, QDA Miner software was used to codify, categorise and analyse the data. To increase the validity and reliability of the data, participant observation was conducted during a five-month stay with the organisation. Finally, various documents and archives were reviewed, allowing cross-method validation (Maxwell, Citation1992).

Table 1: Sample characteristics

4. Findings

The data analysis is presented according to the two main phases of a project lifecycle: project conceptualisation and planning ; and project implementation and closure. These results are not an exhaustive review, but highlight significant points related to the success factors presented in the model.

4.1 Conceptualisation and planning

As already noted, Enablis was founded by the Canada Fund for Africa, Accenture and Telesystem to help southern countries leverage Canadian expertise and the experience of successful business people. The aim was to establish an organisation that could transfer this knowledge and experience to entrepreneurs in the south. However, the founders did not undertake a preliminary needs analysis and only consulted with stakeholders after the organisation had been established. Also, the choice of country was not based on either a request or a need expressed by the government or local participants. Rather, according to the founders, it was determined by the fact that South Africa was a stable country with a certain level of development: ‘South Africa was chosen particularly as a first country because of its relatively more developed infrastructure’ (interview with Top management, 30 August 2011).

The founders also argued that entrepreneurship is innate and does not differ depending on location. But this premise was challenged during the implementation process, when South Africa's entrepreneurial culture quickly became a factor of concern. Comments by South African parties showed that opportunistic entrepreneurship, as opposed to survivalist or necessity entrepreneurship (in the informal sector), is a recent phenomenon. One key factor is education, according to entrepreneurship experts: ‘Our biggest problem is our education system … In South Africa we've got a lot of people who are unemployable.’ Many stakeholders speak of necessity or ‘imitating’ entrepreneurship. As an expert in entrepreneurship pointed out:

The biggest problem is cultural. We don't like taking risks, we would rather go work for a boss … People sometimes don't have very innovative ideas, and if they do, it's normally the same as somebody next to them … You have this huge problem with ‘me too’ businesses. (interview with Entrepreneur 6, 21 February 2012)

Local parties that support entrepreneurship (e.g. the government and banks) and their efficiency are also factors to consider. A preliminary analysis of the project environment could have provided insights into other organisations whose mandate is also to support entrepreneurial development in the country. A senior staff member at Enablis notes:

I don't think they have researched their probable market very well. Because there are other actors, especially in South Africa, there are a number of entities who provide services similar to that of Enablis … South Africa is unique, there are a lot of small business development initiatives on the ground. (interview with Top management, 22 February 2012)

4.2 Implementation and closure

During implementation, the organisation's mission, which at first was solely to support information, communication and technology (ICT) entrepreneurs, evolved in order to meet the community's real needs: ‘At the beginning, it was specifically ICT … However they listened to me, as Enablis would open up its membership to other sectors such as agriculture, tourism, services, transportation, logistics, whatever’ (interview with Partner/donor, 19 May 2012).

As noted, Enablis has branches in various South African cities. Adapting to the cultural dimension of each of the cities has facilitated deep rooting or local ownership of the organisation. In fact, according to a project manager at Enablis:

Even within South Africa, you find that Cape Town does things slightly different than what Johannesburg does. So each city on its own also has its own different culture. I think that in Cape Town you can come to a meeting in flip-flops, where in Johannesburg guys wear a suit [laughs]. (interview with Enablis employee, 14 February 2012)

Hiring local labour for the Enablis offices in Cape Town and Johannesburg contributed to this change. Most of the organisation's employees and the members of its Board of Directors are from South Africa, which means that Enablis is seen as a local rather than a Canadian organisation: ‘It really feels like whatever they have created, it's tailor-made for our situation, which is nice. It doesn't feel like something that's from Canada with Canadian solutions’ (interview with Enablis employee, 14 February 2012). Involving local partners, establishing networking between entrepreneurs, and ensuring grassroots participation contributed to the development of local roots. The Business Plan competition, a local event specifically created by Enablis in South Africa, is a good example of local roots. Interview data, participant observation and documentation confirm the reputation and relevance of this event to the business community.

The entrepreneurs seem satisfied with the services provided, which help them develop much-needed skills. However, they emphasise the need for more effective communication tools, particularly an updated and user-friendly website and a membership database to maximise the impact of the organisation's services. In addition, the training provided to them was based on generic activities related to various themes, instead of a coaching service tailored to their specific requirements. Training is mainly in the form of workshops conducted by external trainers. According to the donor organisation, ‘they have to outsource, you know, the services, so somebody needs to mentor some entrepreneurs. The idea is that you should have this expertise in-house’.

There seemed to be differences in the approach to (or vision for) project management between the donors and Enablis. A senior manager from a major donor organisation says:

They have never been able to understand: why do they need a gender equity policy, why do they need a result-based management, and all these things that a donor would actually insist on having. We forced them to do that … but the problem is they never considered this to be of importance. (interview with Partner/donor, 19 May 2012)

There was also a difference between the donors and the management on the vision for the organisation's goals or expected impact. The administrators regard the ultimate goal of Enablis as helping entrepreneurs prosper and create jobs: ‘The ultimate outcome is we want to get entrepreneurs rich … We train job creators’ (interview with Top management, 30 August 2011). Donors, however, emphasise the organisation's sustainability and a long-term development model which includes a cost–benefit ratio perspective for the help it provides: ‘They are actually driven by things other than developmental objectives, right now. Enablis claims they have more than 1000 entrepreneurs, I don't know, maybe even probably more. Is it enough? I don't think so’ (interview with Partner/donor, 19 May 2012).

However, attitudes are progressively changing and a common language is developing, which facilitates communication and understanding among the parties. According to the donors: ‘The characteristic of that project is something being pushed through, Canadian businessmen actually forced us to think differently’ (interview with Partner/donor, 19 May 2012). This is also reflected in the sustainability of the project and the search for funding. In a context where obtaining funding for NGOs remains difficult, the project shows the importance of involving the business community in international development projects, since it appears easier to call on private partners than on other international lenders: ‘We discussed with other development agencies that are not easily accessible. When you discuss with the French development agency and all that, it's not easy' (interview with Top management, 13 February 2012). summarises all of these findings.

Table 2: Findings from the case study

5. Discussion and conclusion

This article explored the factors influencing the success of an NGO that supports entrepreneurship in South Africa. The article aimed to answer the following question: what are the challenges facing international projects focused on entrepreneurial development? The findings point to four main challenges: transposing a northern business model to the south; developing local roots and adapting to the local context; balancing the allocation of resources between managing the project and providing services to the entrepreneurs; and finding a fit between the culture of the private sector and that of international development agencies. These issues, which go beyond the economic dimension, should be further explored.

5.1 Transposing a northern entrepreneurship model to the south

One of the major challenges facing Enablis was the difficulty of transposing a business model developed in a Northern country (Canada) to a southern country (South Africa). Several studies indicate that understanding the project environment, the role of stakeholders and the local culture during the conceptualisation of the project is an important success factor (Muriithi & Crawford, Citation2003; Khang & Moe, Citation2008; Ika et al., Citation2010; Tremblay et al., Citation2013). This case study adds value to these studies through its comparative analysis of the specific contexts of international development and entrepreneurship, which underlines the importance of understanding the characteristics of these two fields of study.

The study also demonstrates that the initial paradigm, which assumed that entrepreneurs in different locations are the same, was incorrect. This confirms the findings of other studies (Ozgen & Minsky, Citation2007; Mano et al., Citation2012) which show that several components must be adapted to the local culture and that support programmes must take the country's entrepreneurial culture into account. This highlights the need to analyse upfront how the business models will be adapted to transfer expertise in a north–south context and how endogenous practices will be accommodated.

5.2 Developing local roots during implementation

Another important challenge was adapting to the local context and developing local roots during implementation, which involves monitoring and adjusting the project plan based on feedback from the community (Youker, Citation1999; Ika et al., Citation2012).

This study adds value to other studies which show the importance of involving stakeholders during the conceptualisation of the project, and provides guidance on how this can also be done during implementation: adapting the mission, hiring local labour, engaging in networking, and involving local stakeholders. Interventions by Enablis to develop local roots provide new insight into the findings of studies that show the difficulties of fostering local ownership and creating local knowledge of the project (Ramaprasad & Prakash, Citation2003; Ika, Citation2007; Ika et al., Citation2012; Brière & Proulx, Citation2013), especially in view of the organisation's bottom-up approach to growing these roots (Muriithi & Crawford, Citation2003; Anantatmula & Thomas, Citation2010; Ochieng & Price, Citation2010).

The literature underlines the importance of the cultural context and environment (Mitchell et al., Citation2002; Ozgen & Minsky, Citation2007; GEM, Citation2011; Mano et al., Citation2012) in projects for entrepreneurial capacity-building. However, studies on the characteristics that promote entrepreneurial development in terms of social, human and financial capital (Bosman & Gerard, Citation2000; Latha & Murthy, Citation2009; Bloom et al., Citation2010; Bruhn et al., Citation2010) also show that more analysis is needed to better understand the determinants of entrepreneurship in a specific local context.

5.3 Balancing resource allocation between project management and entrepreneurial services

Maintaining a balance in the allocation of resources between the management of the NGO and the services it provides is crucial. On the one hand, the NGO has to hire and train people who can manage it according to the donors’ requirements (gender equity, results-based management, etc.), while on the other it also has to hire or train people to support entrepreneurial development at different levels. The skills of the project managers and the team members are critical to the success of these projects (Diallo & Thuillier, Citation2005; Khang & Moe, Citation2008), especially in establishing a relationship of trust between project managers, their teams, the key stakeholders and the beneficiaries. However, this presents a challenge, as the project managers (and teams) must be highly skilled in both project management and entrepreneurial support. This is part of the debate on the complexity of relationships between entrepreneurship and international development projects, and demonstrates the difficulty of properly assessing the success factors for such projects (Diallo & Thuillier, Citation2004; Ika, Citation2007; Khang & Moe, Citation2008).

In this study, the primary success factor was meeting the needs of the stakeholders and project beneficiaries – in this case entrepreneurs – who required assistance in developing useful skills for their own situations. This underlines the importance of helping entrepreneurs acquire and develop business skills through various support programmes (Ozgen & Minsky, Citation2007). This need to balance the allocation of resources between project management and entrepreneurial services has not yet been fully explored in the literature, and studying this phenomenon from a managerial perspective would be valuable. Studies that focus on the management of international development projects (Khang & Moe, Citation2008; Navarro-Flores, Citation2011; Ika, Citation2012; Ika et al., Citation2012; Okorley & Nkrumah, Citation2012; Brière & Proulx, Citation2013; Hermano et al., Citation2013) and the development of staff skills in NGOs (Diallo & Thuillier, Citation2005; Abbott et al., Citation2007; Brière & Proulx, Citation2013; Hermano et al., Citation2013) are interesting, but there is a need for more contextualised studies on the management practices of NGOs that support entrepreneurship in developing countries.

5.4 Aligning the entrepreneurship and international development cultures

The final result underscores the challenge of aligning the cultures of the private sector and international development agencies. This is often discussed in the literature, but more in terms of hybrid organisations in developing countries carrying out projects under public–private partnerships (Chen et al., Citation2006; Mano, Citation2013; Schmid, Citation2013).

The findings from this case study demonstrate the differences between these two cultures. They support Naudé’s (Citation2010) statement that, although a certain consensus is taking shape in the literature, much remains to be done on integrating entrepreneurship and international development in the field.

Much also remains to be done for private-sector and international aid stakeholders to contribute jointly to the creation of businesses that foster wealth distribution and a better allocation of international aid (Naudé et al., Citation2008; Abdullah et al., Citation2009; Azmat & Samaratunge, Citation2009; Bhagavatula et al., Citation2010; McMullen, Citation2011; Naudé, Citation2011). Further research is needed on the impact of programmes to support entrepreneurs in developing countries, in order to assess their effectiveness (Mathibe & van Zyl, Citation2011). Such research must measure their impact both on the creation of new businesses and on improving their chances of survival, and must include qualitative indicators such as changes in the local climate, participation, lessons learnt and the impact on the community (OCDE, Citation2003; Tremblay, Citation2011; Mano et al., Citation2012; McKenzie & Woodruff, Citation2012). Organisations such as the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, Citation2011) provide an overview of the different types of businesses created. However, studies to assess the types of businesses created (traditional for-profit businesses, cooperatives, family businesses, social enterprises, etc.) and the performance of a particular model would be valuable.

Finally, while the findings of this case study cannot easily be generalised, they can assist both practitioners and researchers. The study illustrates particular partnerships that are emerging in the international development arena, and raises important issues that must be considered in their implementation. At a practical level, the study also sheds some light on innovative projects led by NGOs such as Enablis.

At a theoretical level, the model (shown in ) demonstrated the differences between the entrepreneurial and the international development paradigms. In light of this case study, the model has to consider relevant new indicators of the success of international projects for entrepreneurial development, as well as specific challenges. These include: understanding the particular environment; developing a common understanding among lenders and project partners from the business community; adapting business models in the north–south transfer; developing tailored strategies for implementing a project; establishing a local project team; and balancing the resources allocated to the organisation and to its entrepreneurs.

This case study highlights the need for other studies on these challenges, using an interdisciplinary approach involving international development, economic development, entrepreneurship and management. Based on the proposed model, an in-depth study would demonstrate what management tools would be useful for integrating the perspectives of donors and NGOs that support entrepreneurship. A follow-up study on strengthening the organisational capacity and project management skills of NGOs would also be valuable. Finally, further research is required on qualitative and quantitative criteria for assessing the impact of the resulting SMEs on the economic and social development of the community. Such case studies could usefully involve Enablis, since this organisation has set up chapters in other African countries. They could also use case studies of other organisations with a similar mission, or validate different models presented in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, D, Brown, S & Wilson, G, 2007. Development management as reflective practice. Journal of International Development 19(2), 187–203. doi: 10.1002/jid.1323

- Abdullah, F, Hamali, J, Deen, AR, Saban, G & Abdurahman, AZA, 2009. Developing a framework of success of Bumiputera entrepreneurs. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 3(1), 8–24. doi: 10.1108/17506200910943652

- Anantatmula, V & Thomas, M, 2010. Managing global projects: A structured approach for better performance. Project Management Journal 41(2), 60–72. doi: 10.1002/pmj.20168

- Azmat, F & Samaratunge, R, 2009. Responsible entrepreneurship in developing countries: Understanding the realities and complexities. Journal of Business Ethics 90(3), 437–52. doi: 10.1007/s10551-009-0054-8

- Barès, F, 2004. Que dire de l'accompagnement en phase de démarrage? La perception de cinq créateurs d'entreprises technologiques à fort potentiel de croissance. 3ème Congrès International de l'Académie de l'Entrepreneuriat, Lyon.

- Bester, E, 2012. Enablis Africa region activities report: Q4 Fiscal 2012. Enablis, Cape Town.

- Bhagavatula, S, Elfring, T, van Tilburg, A & van de Bunt, GG, 2010. How social and human capital influence opportunity recognition and resource mobilization in India's handloom industry. Journal of Business Venturing 25(3), 245–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.006

- Bloom, N, Mahajan, A, McKenzie, D & Roberts, J, 2010. Why do firms in developing countries have low productivity? American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 100(2), 619–23. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.2.619

- Bosman, C & Gerard, FM, 2000. Quel avenir pour les compétences? De Boeck, Brussels.

- Bradford, W, 2007. Distinguishing economically from legally formal firms: Targeting business support to entrepreneurs in South Africa's townships. Journal of Small Business Management 45, 94–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00201.x

- Brière, S & Proulx, D, 2013. La réussite d'un projet de développement international: Leçons d'expérience d'un cas Maroc-Canada. Revue Internationale des Sciences Administratives 79(1), 171–91. doi: 10.3917/risa.791.0171

- Bruhn, M, Karlan, D & Schoar, A, 2010. What capital is missing in developing countries? American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 100(2), 629–33. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.2.629

- Bruton, GD, Ahlstrom, D & Obloj, K, 2008. Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00213.x

- Carrier, C & Tremblay, M, 2007. La recherche créative d'opportunités d'affaires: Compétence négligée des organismes québécois d'accompagnement à l'entrepreneuriat? 5ème Congrès International de l'Académie de l'Entrepreneuriat, Sherbrooke, Canada.

- Chen, M-S, Lu, H-F & Lin, H-W, 2006. Are the nonprofit organizations suitable to engage in BOT or BLT scheme? A feasible analysis for the relationship of private and nonprofit sectors. International Journal of Project Management 24(3), 244–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2005.08.002

- Colletah, C, 2000. Culture as a barrier to rural women's entrepreneurship: Experience from Zimbabwe. Gender and Development 8(1), 71–7. doi: 10.1080/741923408

- Della-Giusta, M & Phillips, C, 2006. Women entrepreneurs in the Gambia: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of International Development 18(8), 1051–64. doi: 10.1002/jid.1279

- Diallo, A & Thuillier, D, 2004. The success dimensions of international development projects: The perceptions of African project coordinators. International Journal of Project Management 22(1), 19–31. doi: 10.1016/S0263-7863(03)00008-5

- Diallo, A & Thuillier, D, 2005. The success of international development projects, trust and communication: An African perspective. International Journal of Project Management 23(3), 237–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2004.10.002

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), 2011. Global entrepreneurship monitor: South Africa. UCT Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (CIE), Cape Town.

- Gibb, A, 2005. Towards the entrepreneurial university. National Council for Graduate Entrepreneurship (NCGE), Birmingham.

- Hermano, V, López-Paredes, A, Martín-Cruz, N & Pajares, J, 2013. How to manage international development (ID) projects successfully. Is the PMD Pro1 Guide going to the right direction? International Journal of Project Management 31(1), 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.07.004

- Holcombe, SH, Nawaz, SA, Kamwendo, A & Ba, K, 2004. Managing development: NGO perspectives. International Public Management Journal 7(2), 187–206.

- Ika, LA, 2007. Les agences d'aide au développement font-elles assez en matière de formulation des facteurs clés de succès des projets? Revue Management et Avenir, Mai, 165–82.

- Ika, LA, 2012. Project management for development in Africa: Why projects are failing and what can be done about it. Project Management Journal 43(4), 27–41. doi: 10.1002/pmj.21281

- Ika, LA, Diallo, A & Thuillier, D, 2010. Project management in the international development industry: The project coordinator's perspective. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 3(1), 61–93. doi: 10.1108/17538371011014035

- Ika, LA, Diallo, A & Thuillier, D, 2012. Critical success factors for World Bank projects: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Project Management 30(1), 105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.03.005

- Khang, DB & Moe, TL, 2008. Success criteria and factors for international development projects: A life-cycle-based framework. Project Management Journal 39(1), 72–84. doi: 10.1002/pmj.20034

- Latha, K & Murthy, B, 2009. The motives of small scale entrepreneurs: An exploratory study. South Asian Journal of Management 16(2), 91–108.

- Lim, CS & Zain, MM, 1999. Criteria of project success: An exploratory re-examination. International Journal of Project Management 17, 243–8. doi: 10.1016/S0263-7863(98)00040-4

- Lingelbach, D, De La Vina, L & Asel, P, 2005. What's distinctive about growth-oriented entrepreneurship in developing countries? Working Paper 1. Center for Global Entrepreneurship, San Antonio, TX.

- Mano, R, 2013. Performance gaps and change in Israeli nonprofit services: A stakeholder approach. Administration in Social Work 37(1), 14–24. doi: 10.1080/03643107.2011.637664

- Mano, Y, Iddrisu, A, Yoshino, Y & Sonobe, T, 2012. How can micro and small enterprises in sub-Saharan Africa become more productive? The impacts of experimental basic managerial training. World Development 40(3), 458–68. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.09.013

- Mathibe, MS & van Zyl, JH, 2011. The impact of business support services to SMMEs in South Africa. International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER) 10(11), 101–8.

- Maxwell, JA, 1992. Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harvard Educational Review 62(3), 279–301. doi: 10.17763/haer.62.3.8323320856251826

- McKenzie, D & Woodruff, C, 2012. What are we learning from business training and entrepreneurship evaluations around the developing world? The World Bank Research Observer 29(1), 48–82. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkt007

- McMullen, JS, 2011. Delineating the domain of development entrepreneurship: A market-based approach to facilitating inclusive economic growth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35(1), 185–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00428.x

- Mitchell, RK, Smith, JB, Morse, EA, Seawright, KW, Peredo, AM & McKenzie, B, 2002. Are entrepreneurial cognitions universal? Assessing entrepreneurial cognitions across cultures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 26(4), 9–32.

- Muriithi, N & Crawford, L, 2003. Approaches to project management in Africa: Implications for international development projects. International Journal of Project Management 21(5), 309–19. doi: 10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00048-0

- Naudé, W, 2010. Promoting entrepreneurship in developing countries: Policy and challenges. Policy Brief 4. United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-Wider), Helsinki.

- Naudé, W, 2011. Entrepreneurship is not a binding constraint on growth and development in the poorest countries. World Development 39(1), 33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.05.005

- Naudé, W, Gries, T, Wood, E & Meintjies, A, 2008. Regional determinants of entrepreneurial start-ups in a developing country. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 20(2), 111–24. doi: 10.1080/08985620701631498

- Navarro-Flores, O, 2011. Organizing by projects: A strategy for local development – The case of NGOs in a developing country. Project Management Journal 42(6), 48–59. doi: 10.1002/pmj.20274

- OCDE (Organisation de Coopération et Développement économique), 2003. L'entrepreneuriat et le développement local: Quels programmes et quelles politiques? OCDE, Paris.

- Ochieng, EG & Price, ADF, 2010. Managing cross-cultural communication in multicultural construction project teams: The case of Kenya and UK. International Journal of Project Management 28(5), 449–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.08.001

- Okorley, EL & Nkrumah, EE, 2012. Organisational factors influencing sustainability of local non-governmental organisations: Lessons from a Ghanaian context. International Journal of Social Economics 39(5), 330–41. doi: 10.1108/03068291211214190

- Ozgen, E & Minsky, BD, 2007. Opportunity recognition in rural entrepreneurship in Developing Countries. International Journal of Entrepreneurship 11, 49–73.

- Preisendorfer, P, Bitz, A & Bezuidenhout, FJ, 2012. In search of black entrepreneurship: Why is there a lack of entrepreneurial activity among the black population in South Africa? Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 17(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1142/S1084946712500069

- Ramaprasad, A & Prakash, A, 2003. Emergent project management: How foreign managers can leverage local knowledge. International Journal of Project Management 21(3), 199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00094-7

- Ras, P & Vermeulen, W, 2009. Sustainable production and the performance of South African entrepreneurs in a global supply chain. The case of South African table grape producers. Sustainable Development 17(5), 325–40. doi: 10.1002/sd.427

- Ryfman, P, 2009. Les ONG. Éditions La Découverte, Paris.

- Schmid, H, 2013. Nonprofit human services: Between identity blurring and adaptation to changing environments. Administration in Social Work 37(3), 242–56. doi: 10.1080/03643107.2012.676611

- SEDA (Small Enterprise Development Agency), 2009. Small business monitor. SEDA, Pretoria.

- Shane, S & Venkataraman, S, 2000. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review 25(1), 217–26.

- Silverman, D, 2010. Qualitative research. Sage, London.

- Steyart, C & Katz, J, 2004. Reclaiming the space of entrepreneurship in society: geographical, discursive and social dimensions. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 16(3), 179–96. doi: 10.1080/0898562042000197135

- Tremblay, M, 2011. Identification collective d'opportunités: Une étude exploratoire. PhD thesis, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada.

- Tremblay, M, Brière, S, Daou, A & Baillargeon, G, 2013. Are Northern practices for supporting entrepreneurs transferable to the South? Lessons from a Canadian experience in South Africa. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 14(4), 269–79. doi: 10.5367/ijei.2013.0127

- UN-Habitat (United Nations Human Settlements Programme), 2006. Innovative policies for the urban informal economy. UN-Habitat, Nairobi.

- Webb, JW, Tihanyi, L, Ireland, RD & Sirmon, DG, 2009. You say illegal, I say legitimate: Entrepreneurship in the informal economy. Academy of Management Review 34(3), 492–510. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2009.40632826

- Youker, RB, 1999. Managing international development projects, lessons learned. Project Management Journal 30(2), 6–7.