Abstract

This article explores community perceptions on implementation and impacts of the Mhakwe Comprehensive Community Initiative (CCI) in Mhakwe Ward, Zimbabwe. A mixed-methods research methodology was adopted. Qualitative data were collected from action research, focus group discussions and key informant interviews. Quantitative data were collected using a structured questionnaire from a random cluster sample, and were analysed using SPSS and Stata with binomial logistic regression to determine factors significantly affecting selected variables and the chi-square test for independence to determine association between variables. Thematic reviews were utilised to analyse qualitative data. Community perceptions on issues affecting multi-stakeholder collaborations, ownership, and control, internal and external enabling factors were explored. The article concludes that leadership development, strengthening family institutions, enhancing ownership and building capacity of local institutions to coordinate such initiatives are fundamental building blocks for CCIs. This article recommends CCIs as a practical framework for empowering marginalised communities.

1. Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, the realisation of the complexity of tackling poverty and the need to revitalise communities led to the proliferation of Comprehensive Community Initiatives (CCIs) (Aronson et al., Citation2007; Makhoul & Leviten-Reid, Citation2010). CCIs aim at improving capacity for self-development within marginalised communities. The fundamental building blocks of CCIs comprise; comprehensiveness; multi-sectoral focus, community and strength-based strategies; long-term planning horizon; their collaborative nature; adaptation to internal and external factors; and promotion of local innovations (Baum, Citation2001; Messinger, Citation2004; Kubisch, Citation2005; Gardner et al., Citation2010; Gardner, Citation2011). They are comprehensive with regards to aiming for systemic change within communities, through addressing multiple developmental issues and utilising multiple approaches. Inter-relationships among different elements, emergent properties and synergies are recognised. CCIs promote community-wide development through integrated investments cutting across various sectors such as social services, health care, education, economic empowerment, local leadership development, institutional building, information communication technologies (ICTs) and youth skills development (Murphy-Berman et al., Citation2000). They apply a multi-stakeholder and multi-level approach incorporating stakeholders that include government departments, community organisations, business and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). CCIs address issues at family, community and regional levels. These initiatives enhance community ownership through addressing priority issues based on local research, and experience. Such a process empowers community members to identify and manage priority activities, taking into account voices of the marginalised. CCIs incorporate empowerment with capacity-building interventions and promote consensus through dialogue in developing a shared vision and community-wide decision-making. They empower communities to control resources and develop monitoring mechanisms.

CCIs recognise that communities cannot be rebuilt or strengthened by focusing on needs, problems and deficiencies. Focus is placed on identifying skills and capacities within community members and local institutions and enhancing decision-making by local communities. They promote harnessing of individual and community assets, strengths and resources as a strategy for development. Their incremental approach allows tackling interrelated problems while taking advantages of opportunities that arise to pursue strategic partnerships and potential synergies to address complex problems. CCIs are normally driven by drivers or priority projects that trigger and stimulate multi-sectoral development. They recognise the dynamic nature of challenges and opportunities, both internal and external, that impact on tackling poverty and other development issues. CCIs incorporate evaluation and learning to allow innovation and continuous improvement.

Most of the literature on CCIs focuses on urban poor communities in the USA and CanadaFootnote4 (Messinger, Citation2004). The state of CCIs in Africa remains undocumented, although funding agencies such as the WK Kellogg Foundation, a US-founded private organisation, attempted to fund such initiatives during the last decade.Footnote5 The purpose of this article is to explore the design and implementation of CCIs and provide empirical evidence for CCIs in an African context using a case study from Mhakwe in Zimbabwe. The specific objectives were to:

assess community perceptions on a multi-sector approach applied by the Mhakwe CCI;

understand the dynamics on community priority needs, ownership and control of the Mhakwe CCI;

assess community perceptions on priority development drivers;

review community perceptions on multi-stakeholder partnerships and collaborations;

assess internal and external enabling conditions for the Mhakwe CCI; and

evaluate perceived impacts of the Mhakwe CCI.

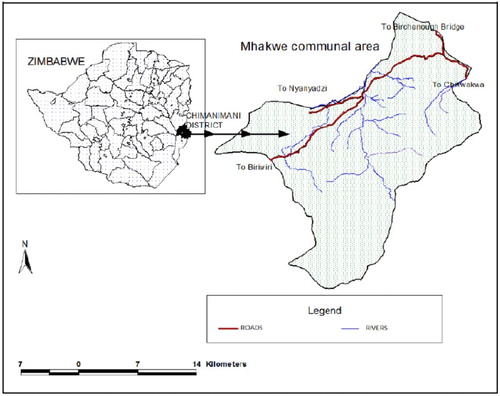

2. Study area

The CCI social experiment funded by WK Kellogg Foundation was implemented in Mhakwe Ward located in Chimanimani District of Zimbabwe. Chimanimani is a predominantly rural district situated 155 kilometres south-east of Mutare in the Eastern Highlands of Zimbabwe. ( shows the location of Mhakwe Ward.) Mhakwe Ward has a total land area of 6290 hectares of which 486 hectares are arable. The Ward has an estimated population of 2483 of which 52% are female. It has 624 households with an average household size of four people (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2012). The Ward has six villages (Chikutukutu, Mandidzidze, Muchada, Mukowangedai, Nechirinda and Zimunda) led by village heads under the Muusha chieftainship.

Mhakwe is located in agro-ecological region three, which is characterised by sandy, acidic soils and receives an average annual rainfall of 600 to 850 mm. The area is suitable for semi-intensive farming, for livestock, fodder and staple cash crops such as maize, tobacco and cotton (Harford & LeBreton, Citation2009). The area is characterised by erratic rainfall and low fertility and is subject to seasonal droughts and severe mid-season dry spells. Agriculture is the dominant activity, with 95% of the people being peasant farmers. The farmers engage in crop and livestock production systems on plots of less than 1.5 hectares. Other household income-generating activities include: craft making, wood carvings, carpentry, pottery, thatching, garment making, Bee keeping (apiculture), poultry, and gardening.

The people of Mhakwe are predominantly of the Ndau ethnic group, which is one of the Shona dialects. The Ndau people are also found in the adjacent parts of Mozambique all the way to the coast. The Mhakwe leadership and most of its people are of the Moyo Chirandu totem and are believed to have originated from Mbire (in the 1800s), around Great Zimbabwe in the south-eastern part of Zimbabwe. Cultural organisation centred on the Ndau dialect is key to the organisation and family unity in the Ward.

Official data on poverty levels in Mhakwe Ward are scarce. However, national statistics indicate that 76% of rural households in Zimbabwe are poorFootnote6 (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2013). In the last two decades, Mhakwe Ward received funding from a number of NGOs in an attempt to address poverty and other development challenges. Such NGOs include WK Kellogg Foundation, Save the Children (USA), Caritas, Christian Care, Family AIDS Caring Trust, Windows of Hope, Help Germany, European Union and catholic Relief Services. Investments from the NGOs covered areas such as agricultural inputs support, water and sanitation, HIV and AIDS support, food aid, support for orphans and vulnerable children, school bursaries and infrastructural development. A number of local institutions spearhead development activities in the Ward, some riding on the external assistance provided by the external NGOs. The notable are the Mhakwe Development Trust, Orphanage Committees, Village and Ward Development Committees, School Development Committees, Irrigation committees, Commodity associations, Water Management committees and Community Garden Committees. The balance and intervention of NGOs and their working relationship with local institutions are important to the development discourse. Key matters that arise include whether such interventions are making a difference in the life of the Mhakwe people, or not, and how? Making an impact analysis is therefore key to identifying the differences that such agencies have, including the extent to which they have built the capacity of local agencies to continue with development interventions. Here lie the core arguments and evidence generated by this article.

3. Conceptual overview of the Mhakwe Comprehensive Community Initiative

The Mhakwe CCI was funded by the WK Kellogg Foundation from the period 2004–10. The main objective was to facilitate broad-based transformation, across key development sectors (businesses development, youth skills development, leadership development, ICTs, early childhood development, adult literacy, HIV and AIDS support, and cultural preservation) while appreciating their interconnectedness. The CCI was based on a community empowerment paradigm that aimed at building community capacity for ‘self-drive’ through building a number of competencies within the community. Such competencies included capacities to analyse one's own situation, articulate desired changes, develop lifelong learning, create strategic partnerships, act and self-correct (WK Kellogg Foundation Africa Program, Citation2005).

A fundamental component was the assumption that such capacities could be developed within the community through strengthening of existing local institutions at all levels (family, village and ward) to build capacity for self-development. Strengthening such institutions entailed investing in multi-sector projects at the various levels. At the family level, investments included entrepreneurship training and revolving facilities to fund family-based business enterprises. The village-level investments covered leadership development, water and sanitation, horticulture, early childhood education and adult literacy. Ward-level projects included the multipurpose ICT centre, HIV and AIDS support projects, cultural promotion, community-based monitoring and evaluation, and community documentation which built capacity for local youths in establishing a community newsletter for knowledge sharing and writing of reports on community meetings.

A core aspect of the Mhakwe CCI was creation of ownership by the community with regards to decision-making and control of resources. The WK Kellogg Foundation entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with the Mhakwe community which related to the community as partners rather than donor fund recipients. This arrangement gave the community the power to prioritise interventions, to monitor and evaluate, and to enter into partnerships with strategic partners. Strategic partners who were identified included Africa University, Mutare Poly Technical College, Government Ministries (Education Sports and Culture, Agriculture, ICT) and private-sector companies. shows the Theory of Change for the Mhakwe CCI. The left side shows the key inputs by the WK Kellogg Foundation, which included facilitation and grant-making, investments in institutional development for local institutions and brokering for strategic partnerships. Multi-sector interventions that were prioritised by the community are highlighted, which lead to the expected outcomes. The CCI was implemented within the context of external and internal socio-economic, political, cultural and environmental factors ().

4. Research design

The study utilised a convergent mixed-methods research design, where qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently and analysed jointly to complement each other (Tashakkori & Teddlie, Citation2003; Creswell & Clark, Citation2011). Qualitative methods enhanced generation of diverse and in-depth perceptions on the Mhakwe CCI, while quantitative methods aimed at generalisable data for statistical inferences. Quantitative data were collected using a structured questionnaire, with questions guided by the research questions.Footnote7 Respondents were randomly selected using a two-stage process. The community was firstly organised into 28 clusters that represented socio-economic activities in the Ward. Samples were then drawn randomly from the clusters. A total of 65 households were interviewed. Quantitative data were coded, entered and analysed using SPSS Version 21 and Stata version 10. Data were cleaned and analysed using non-parametric statistical methods. Binomial logistic regression was utilised in establishing factors that statistically effected specific perceptions, while chi-square tests of independence were utilised to determine association between variables.

Qualitative data were collected through key informant interviews, focus group discussions, field notes and review of community documentation. Key informants were purposively selected using experiential knowledge, as the researcher had been involved for more than eight years in action research with the community, working as a facilitator for the Mhakwe CCI. Key informants were regarded as individuals with the capacity to represent community-wide perceptions. The facilitation involved cycles of planning, implementation, reviews and learning with the community. A total of nine interviews were conducted with identified key informants who participated in the programme and seven interviews were conducted with non-participants. The total number of key informants who were interviewed was guided by the concept of saturation (Mason, Citation2010). The point of saturation occurred when interviews no longer produced any new or additional knowledge. Four focus group discussions were conducted with representatives for youths, women, leaders (traditional and opinion leaders) and non-beneficiaries because these represented the key community interest groups. The groups had an average of nine people. Focus group discussions allowed in-depth exploration of perceptions, experiences, insights and beliefs by different community groups on the Mhakwe CCI. Field notes by the researcher, minutes of community meetings, formative and summative evaluation reports were also reviewed. Qualitative data were analysed through thematic reviews,Footnote8 in which responses were grouped into themes and analysed (Patton, Citation2002).

5. Findings from Mhakwe

5.1 Community perceptions on priority development drivers

Development is shaped by priority needs; in this context the study sought to identify the priority needs in their ranking order. The results from the quantitative interviews (N = 65) show that the top-five priority drivers for the Mhakwe CCI were: leadership training (15%); family-based business enterprises (15%); youth training (14%); village projects (12%); and resources for revolving funds to support projects (11%). Other minor drivers were identified as: early childhood development (8%); adult literacy (8%); ICTs (6%); community multipurpose resource centre (5%); community newsletter (3%); and assistance for vulnerable children and orphans (2%).

The chi-squared test for independence at a 95% confidence interval showed no significant association in perceptions for the prioritised sectors with socio-economic characteristics of respondents (age, education level, marital status, leadership position in the community, gender, village, and beneficiary status from the programme). However, statistically significant associations were found between perceptions on priority sectors and perceptions on interests served by WK Kellogg Foundation ( = 44.3686; p = 0.026), perceptions on linkages of the Mhakwe CCI with ongoing programmes (

= 36.9490; p = 0.001) and perceptions on necessary internal conditions that affected success of the Mhakwe CCI (

= 59.0308; p = 0.042). The key reasons for identifying the priority sectors were focus on community planned projects (20%), addressing needs of every age group (22%) and improving self-reliance (25%).

The results from focus group discussions with youth representatives on 21 August 2013 at Mhakwe Primary School brought some different insights, as highlighted in the following selected quotations:

The program was driven by capacity building of an individual then gradually moving to the family which is the basic building block of a village or ward. It was believed that an individual or family with a positive mind-set would zoom that influence to the whole village or ward.

They addressed the issue of ICTs, constructed community structures for village meetings, sent youths to schools, repaired boreholes and conducted exchange programs. In my understanding, these were important drivers because the community is now recognised as an information centre hub.

5.2 Perceptions on community ownership and control of the programme

The issue of programme ownership is contested in Zimbabwe. There is a view that NGOs want to be identified by the projects, as seen through labelling the aid their give and also putting banners with their logos in project sites. They are also viewed as being driven by external agendas influenced by funding agencies (Porter, Citation2003). At the same time, they also expect community ownership, yet communities are also smart enough to the extent that they identify projects by the name of the donor rather than their own local lexicon. However, the study found that in Mhakwe 63% of respondents perceived the programme as being driven by the community. This perception had statistically significant association with the village of respondents ( = 12.733; p = 0.026), leadership position (

= 3.965; p = 0.046) and by whether or not respondents participated in programme evaluation exercises (

= 4.229; p = 0.040). With regards to ownership and control of the CCI, 60% felt that the programme was owned and controlled by the Mhakwe community while 9% felt it was under the Mhakwe Development Trust, 25% perceived traditional leaders as owners and 15% felt ownership and control was under WK Kellogg Foundation. Focus group discussions gave mixed perceptions on control and ownership. An example quotation is as follows:

The community and teachers were not fully consulted to understand their needs. Few individuals who were consulted did not say the people's needs but their own lines of thinking. Important people's needs were left out by not consulting the people as a whole including the marginalised.

Traditional leaders managed to gather people at meetings to identify priority needs; the problem was that these needs were not included in some projects:

During the Zimbabwean Dollar era, the program used to specify how much money was put into Mhakwe Development Trust for projects, we knew exactly how much each village was supposed to get and this made us feel we owned the program. Currently we feel that the program belongs to Mhakwe Development trust because they are in charge of the resources.

Binomial logistic regression was run to determine factors that influence perception on community ownership and control with dependent dummy variables (1 = community ownership and control, 0 = ownership and control by other institutions). Iterations with various variables led to a model containing seven independent variables (village where respondents reside, leadership position in the community, perceptions on external factors that affect the CCI, support from local government departments, engagement in community dialogue, household head status and gender of respondents). The full model containing all of the predictors was statistically significant (p = 0.0006) and R2 = 0.2931 (see ). As shown in the table, three independent variables (village, engagement in community dialogue and household head status) made a statistically significant contribution (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 1: Binomial logistic regression results

5.3 Community perceptions on multi-stakeholder partnerships

The Mhakwe CCI was premised on partnerships among a variety of stakeholders with different responsibilities. Results from interviews and key informants indicate that the key local stakeholders were the Mhakwe Development Trust, local schools, local government departments, community support groups (cultural promotion groups, HIV and AIDS support groups), commodity associations, traditional and elected leaders, other NGOs, Chimanimani Rural District Council, the Mhakwe multipurpose centre management committee and local police.

The chi-square tests for independence found no statistically significant associations among groups (by highest level of education, gender, leadership position, marital status) with perceptions on roles of stakeholders in the Mhakwe CCI. However, statistically significant associations (p ≥ 0.05) were found for age and role of local extension department, age and role of Chimanimani Rural District Council, and beneficiary status and roles of Mhakwe Development Trust, Village Development Committees, Chimanimani Rural District Council (the district governing authority) and Mhakwe Multipurpose ICT Centre.

Results show that 86% perceived the Mhakwe CCI as having linkages with ongoing programmes that were already being implemented before its inception. However, perceptions on links did not have any statistically significant association with perceptions on programme success ( = 6.6375, p = 0.156). The type of linkages highlighted include assisting ongoing projects (25%), complementing ongoing training programmes (14%), some WK Kellogg Foundation projects being sustained by other NGOs (20%) and other NGOs adopting the WK Kellogg Foundation model (11%).

Results from focus group discussions held at Mhakwe Primary School on 21–23 August 2013 identified problems with regards to power dynamics among traditional leaders as well as between some traditional leaders and the Mhakwe Development Trust. Some traditional leaders felt there was unfair allocation of financial resources among villages, although villages were funded based on their priorities and proposals submitted to Mhakwe Development Trust. Other traditional leaders felt that the Mhakwe Development Trust was running the programme based on its own decisions without consensus from the traditional and elected leadership. Results indicated contestations among various NGOs working within the Mhakwe CCI on the ownership of some village projects; an example is the Dembweni Community garden in Chikutukutu Village that was established by Caritas Zimbabwe and was now incorporated as a village project in the CCI.

5.4 Perceptions on internal and external enabling conditions

Internal conditions perceived as important for success of the Mhakwe CCI were the community being apolitical in planning and project implementation (37%), having a common community vision (29%), respecting local culture (11%), having strong local institutions (9%) and commitment by the community to the programme (9%). Chi-square tests for independence show that these perceptions were not associated significantly (p ≥ 0.05) with age, gender, education level, village and leadership status. The study identified key external factors as political interference from politicians (65%) and delays in disbursement of funds by the funding agency (17%). However, these perceptions were statistically associated with the village where respondents resided ( = 49.3219, p = 0.015) and perceptions on the roles of NGOs in local development (

= 62.1580, p = 0.023). The top-five perceived roles of NGOs in local development were associating NGOs with free money (25%), provision of agricultural inputs and food aid (20%), NGOs leaving unfinished and unsustainable projects (15%), teaching people about development (12%) and augmenting government efforts in assisting communities (12%).

Focus group discussions identified internal conditions that impacted negatively on the programme, as highlighted in the following quotation:

The same people such as Village Heads were involved in the training programs, leaving behind the rest of the people. The program gave priority to local leadership at the expense of the generality of poor community members.

The CCI had a thrust for strengthening local institutions. This led to a continuous need for investing in leadership training to enhance transformative leadership within these institutions. There was a general observation during action research that some community members viewed participation in training as a way of benefiting from travelling because some training programmes were conducted outside Mhakwe. In fact, there was belief by some community members that traditional leaders were making money from being trained. It appears the agenda for the training was not understood particularly by community members who were not directly benefiting from the programme, as evidenced by a significant association between perceptions on the importance of leadership training and beneficiary status ( = 13.5288; p = 0.019).

5.5 Local perceptions on the impacts of the Mhakwe Comprehensive Community Initiative

CCIs are expected to impact positively in improving livelihoods for the intended beneficiaries. The study shows that 35% rated the Mhakwe CCI as successful while 57% rated it as fairly successful and 8% felt it had failed. Some of the reasons why the programme was perceived to have failed are given in the following quotations form a focus group discussion with representatives of community leaders and non-beneficiaries and key informant interviews held on 22 August 2013:

I am biased towards agriculture; at the moment my own thinking is that the program failed in addressing poverty. A lot of people in the community right now do not know where the next dollar to buy mealie meal will come from. If agriculture succeeds and people get sustainable sources of food that will be the end of poverty.

The program did not succeed due to very poor or inconsistent methods of supervision, poor financial management and accounting methods, low levels of responsibility by the community and failure to have clear and sound financial policies and procedures.

Water extraction projects were not a success because of the methods used. For example, Chikutukutu water project used electricity that in the first place was not suitable considering operational costs. Extracting water from underground sources or a river using electricity is not viable at all in my own option. This was a wrong choice of project and resources were wasted.

Most projects were not completed. The water tank in Chikutukutu village was constructed and community member dug trenches for piping but temporary measures were taken and piping was not completed. People were left with taps but no water. The borehole in Mandidzidze village was also not completed.

The study found a statistically significant association of the ratings of programme success with the village respondents came from ( = 25.2636; p = 0.005). Interestingly, the perceptions on these ratings were not significantly associated with perceptions on whether or not the Mhakwe CCI addressed priority community issues and perceptions on who owned and controlled the CCI (p ≥ 0.05). Key beneficiaries were identified as youths (31%), women (23%) traditional leaders (13%) local schools (9%) and Mhakwe Development Trust (4%). Frequencies for perceived key benefits from the CCI were capacity-building for self-development (20%), financial resources for projects (20%) leadership skills (13%), confidence-building (12%), awareness of development issues (12%) and exposure to other projects (6%).

The chi-square tests for independence between beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries showed statistically significant association with perceived impacts of the CCI on ICTs and youth training sectors (p ≤ 0.05). There were no significant associations for the perceived impacts on ICTs, youth training, village projects, adult literacy and leadership training among groups with age, village, education level, leadership position, gender and marital status (p ≥ 0.05).

6. Discussion

Results from the study identify leadership development as a key factor in driving a multi-sectoral approach in CCIs. The leadership development approach utilised by the Mhakwe CCI was based on action research with cycles of planning, action, observations, reflections and responsive leadership capacity development. This allowed leadership skill development through experiential and reflective learning while addressing practical problems during implementation of projects (Burns, Citation2007; Barton et al., Citation2009). The importance of leadership development through experiential and reflective learning supports findings by Kubisch et al. (Citation2010) and Walakira (Citation2010) that indicate the importance of leadership development in empowering local leadership in tackling developmental challenges. In the Mhakwe CCI, focus group discussions with women and leader representatives indicated that some traditional leaders who are in charge of the Village Development Committees were not clear on their roles in development, with most of them concentrating more on cultural issues. In addition, most community leaders are accustomed to fragmented development projects that are sector specific. Leadership development was important in building capacity for coordinating multiple sectors and stakeholders within the CCI. Leadership development through experiential and reflective learning for leaders in Mhakwe yielded a number of successful qualitative impacts, including building confidence and improving innovation where some villages such as Chikutukutu initiated water projects and mechanisms for managing such projects.

Building strong family institutions through promotion of family-based business enterprises was identified as a key driver in the Mhakwe CCI. Evidence from the study shows that households which benefited from family business investments participated more in community dialogue. Interactions between the researcher and the community at various community meetings showed that women from such households (e.g., women from Tigere Poultry Group – a poultry producer association for poultry family businesses) became more confident, participated more in community meetings and were empowered to challenge the Mhakwe Development Trust for accountability on the use of project funds. It was also observed that such families became proactive in engaging partners for their businesses, as evidenced by new partnerships with partners such as Buffalo (a private agribusiness) and Mutare Poly Technical College for poultry exhibitions. Such empowered families have been found to have huge spill-over effects in community development; for example, Connell & Aber (Citation1995) in their resilience research indicate strong families as crucial contributors to youth development through behavioural guidance and supervision. Murphy-Berman et al. (Citation2000), in an evaluation of CCIs in Nebraska, USA, highlight the importance of empowering families in reducing youth crime and increasing educational achievements.

In this study, community perceptions on key sectors that drove the Mhakwe CCI were found to be significantly associated with: perceptions on interests served by the funding agency (i.e. whether or not the programme served the community); perceptions on linkages of the CCI with existing programmes; and perceptions on necessary internal conditions for success. Literature on CCIs is silent on how key driving sectors are prioritised within communities. Prioritisation of sectors for the Mhakwe CCI was done through a participatory process at the village level, which did not incorporate such perceptions. This study recommends that these perceptions should be mapped out and be incorporated during the planning phases in determining key driving sectors for future CCIs. Such a process will probably ensure that identified sectors are representative of community priorities. The planning phase for the Mhakwe CCI involved engagement and consultations, community mapping and strategy development. Engagement and consultations with community leadership allowed a common understanding on the goals of the CCI. Community mapping and strategy development involved identification and prioritisation of required services as well as identification of stakeholders, developing strategies for stakeholder collaboration and mechanisms for the coordination of the CCI. According to Murphy-Berman et al. (Citation2000), these planning stages are critical in ensuring that proposed interventions and institutional arrangements represent the priority needs of the people, and not needs imposed on them.

A statistically significant association was observed between perceptions on priority needs and village, leadership position and participation in evaluations. Although prioritisation of community needs was conducted at the village level, the ultimate choice of interventions was prioritised at the ward level based on issues that were felt to be cross-cutting. Chances are that some villages were compromised since villages are heterogeneous in resource endowment. The importance of accurate priority needs is supported by Lyndon et al. (Citation2011), who attribute failure of some initiatives to the lack of understanding of the worldview, social system and culture of communities. Although a majority of the respondents (60%) felt the Mhakwe CCI was owned by the community, there were concerns that benefits accrued to a few families who participated in multiple projects. Focus group discussions with non-beneficiaries on 22 August 2013 linked the selection bias to the fact that, although initial selections were made at village level through consensus, subsequent selections were made by some traditional leaders without consultations from the community. Such scenarios have been found to create inequity because continuous capacity-building of a few selected families at the expense of reaching other new families can lead to an increase in livelihood gaps within communities (Platteau & Gaspart, Citation2003; Labonne & Chase, Citation2009).

Logistic regression results show that perceptions on ownership of the Mhakwe CCI were influenced by the village where respondents reside, engagement in community dialogue and household head status (male or female headed). This could possibly be explained, firstly, by the fact that villages benefited differently from the programme. Some villages such as Chikutukutu were perceived to have benefited more than other villages, and hence residents of the village would probably feel they owned the programme more than those from other villages. Chikutukutu village was stronger than other villages with regards to brokering support from WK Kellogg Foundation Facilitators; for example, the village managed to develop a bankable proposal for a micro-irrigation project that was more competitive than proposals from other villages. Secondly, villagers who frequently engaged in community dialogue would be more informed about the programme, and hence would probably feel they owned the programme more than those less informed. Finally, the Mhakwe CCI had a bias to the empowerment of women (guided by the WK Kellogg Foundation focus on women and youth empowerment). It is therefore highly probable that woman would feel they owned the programme more than men.

Results from the chi-squared test for independence show statistically significant associations between age and perceived roles of local extension departments and Chimanimani Rural District Council. This might be explained by the fact that services offered by the institutions affected different age groups differently. For example, extension services within the CCI would be viewed differently by the elderly (older than 60 years) who would not be actively involved in agriculture compared with younger villagers. Chi-squared tests also showed a statistically significant association between beneficiary status (whether or not respondents benefited directly) and the role of Mhakwe Development Trust, which coordinated the CCI. This could possibly be explained by the fact that information dissemination by the Trust favoured beneficiaries of the programme. This study recommends equal information dissemination for both beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries within CCIs to enhance a common appreciation of the roles of local institutions that coordinate CCI activities to enhance utilisation of services offered.

Political interference was identified as a key external factor that negatively affected operation of the Mhakwe CCI. Such experiences were highlighted in focus group discussions with community leader representatives on 23 August 2013 at Mhakwe Primary School, where some politicians tried to ride on the success of the Mhakwe CCI for political campaigning during election periods. This was said to have impacted negatively on the CCI through diverting dialogue from addressing developmental issues towards political issues, distorting selection of beneficiaries towards political affiliation and disruption of programme activities by local institutions towards political campaigning. These findings were also supported by Chabal and Daloz in Platteau & Gaspart (Citation2003), who identified abuse of CCIs by politicians as a key success factor in CCIs. Although the community attributed being apolitical in programme activities as a key internal success factor, this did not apply throughout the project period because some key community leaders were lured into political activities. Elected leadership, particularly the Councillor, would periodically be changed after election periods, and this impacted the programme negatively because at times the new leader might not have been participating in the programme and would have to be oriented for continuity.

The study identified community capacity-building for self-development as the key benefit from the Mhakwe CCI. This is in line with the core objective of CCIs (Chaskin, Citation2001; Lafferty and Mahoney, Citation2003). The top-five cases reflecting community empowerment from the quantitative survey were: community now able to manage projects (21%), households affording to pay school fees (15%), rising numbers of profitable businesses (13%), increased confidence by local leadership (13%) and community projects still running after WK Kellogg Foundation exit (12%). The evidence was supported by focus group discussions held with youth and women representatives on 21 August 2013 and 23 August 2013 respectively, which identified evidence of empowerment at the family level to include improved household incomes as evidenced by reduced dropout rates of children from schools and reduced rates of malnutrition (quantitative figures were not provided). At the village level, evidence of empowerment that was identified included improved capacity of Mhakwe Ward to advocate for improved services from Chimanimani Rural District Council (the district governing body), particularly the need for the district engineer in designing plans for the Mhakwe Multipurpose Community Centre, and the district ICT department to train youths in computer maintenance. Other evidence highlighted include improved capacity for event management (evidenced by improved quality and numbers of events such as agricultural shows), and improved capacity of community-based monitoring and evaluation activities as evidenced by documentation in the Mhakwe Development Trust offices.

7. Conclusion

This study evaluated the design and implementation of the Mhakwe CCI in Zimbabwe. Evaluation studies on CCIs have, firstly, had a bias towards CCIs in the USA and Canada, with scarce evidence and experiences on CCIs in Africa, and have, secondly, been biased towards impact evaluation with little focus on process evaluation. The study concludes that leadership development, family-based business enterprises, youth training, village-level projects and revolving funds for projects were the key drivers for the CCI. Leadership development needs to be based on action research and experiential learning because this empowers local leadership in coordinating multiple sectors and multiple stakeholders engaged in CCIs. Strong family institutions are critical in CCI as they have spill-over effects in local development, including confidence-building, engaging strategic partners and increased participation in community dialogue. Strategies for ensuring community ownership of CCIs should take into cognisance the heterogeneity of community members with regards to villages, leadership positions and participation in evaluations because these were found to be significantly associated with perceptions on ownership and control.

Multi-stakeholder and multi-sectoral partnerships are important in CCIs. However, such partnerships should create linkages with ongoing community initiatives. There is a need for strengthening and empowering local coordinating institutions for the CCI, since most local institution have traditionally coordinated fragmented and sector-specific development projects. Strategies and modalities for partnerships should be clearly developed at the onset of CCIs because in some instances there might be competition for space and recognition for success of particular components of a CCI by some partners, particularly NGOs. Integrating risks of internal and external enabling conditions is critical for CCIs. Political interference by politicians was identified as a potential external risk for CICs. Sensitising communities on the impacts of such risks could enable development of mitigating mechanisms.

This study concludes that CCIs provide a practical framework for empowerment of marginalised communities in Africa. However, studies still need to be conducted in improving the capacity for local institutions in coordinating multi-stakeholders and multiple sectors within CICs. Although this study identified impacts of CCIs on community empowerment for self-development, it did not explicitly assess the interconnectedness and synergies among various sectors and stakeholders. Such knowledge would be critical in understanding the systemic nature of CCIs. It is recommended that future evaluation studies on CCIs should dwell more on understanding the inter-relatedness of various sectors and stakeholders within CCIs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

4Examples include the Vibrant Communities Program that works with 12 municipalities and the Action for Neighbourhood Change in Canada (Makhoul & Leviton-Reid, Citation2010).

5These were coordinated by the Africa Programs and operated in eight southern African countries from 2005 to 2010, before the programme was wound up.

6These figures are based on the consumption expenditure approach that uses per-capita consumption expenditure indices combined with household characteristics such as asset ownership and access to social services (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2013).

7The questionnaire covered areas including socio-economic and demographic characteristics, asset ownership, engagement with NGOs, perceptions on effectiveness and perceived impacts of the Mhakwe CCI, and perceived drivers for local development.

8Analysis focused on recurring themes from group consensus, identification of most noteworthy quotes and unexpected and controversial findings. Notes were compared with transcriptions from audio-recordings to ensure reliability.

References

- Aronson, RE, Wallis, AB, O'Campo, PJ, Whitehead, TL & Schafer, P, 2007. Ethnographically informed community evaluation: A framework and approach for evaluating community-based initiatives. Maternal and Child Health Journal 11, 97–109. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0153-4

- Barton, J, Stephens, J & Haslett, T, 2009. Action research: Its foundations in open systems thinking and relationship to the scientific method. Systems Practice and Action Research 22, 475–88. doi: 10.1007/s11213-009-9148-6

- Baum, HS, 2001. How should we evaluate community initiatives? Journal of the American Planning Association 67(2), 147–58. doi: 10.1080/01944360108976225

- Burns, D, 2007. Systemic action research: A strategy for whole system change. The Policy Press, Bristol.

- Chaskin, RJ, 2001. Building community capacity: A definitional framework and case studies from a Comprehensive Community Initiative. Urban Affairs Review 36(3), 291–323. doi: 10.1177/10780870122184876

- Connell, JP & Aber, L, 1995. How do Urban Communities Affect Youth? Using social science research to inform the design and evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives. In Connell, JI, Kubisvh, A, Schorr, LB & Weiss, CH (Eds.), New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: Concepts, methods and contexts. The Aspen Institute, New York. pp. 93–125.

- Creswell, JW & Clark, VL, 2011. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage, London.

- Gardner, B, 2011. Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Promising directions for ‘wicked’ problems? Horizons Policy Research Initiative, Wellensley Institute, Toronto.

- Gardner, B, Lalani, N & Plamadeala, C, 2010. Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Lessons, potential and opportunities moving forward. Wellesley Institute, Toronto.

- Harford, H & LeBreton, J, 2009. Farming for the future: A guide to conservation agriculture in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Conservation Agriculture Task Force, Harare.

- Kubisch, AC, 2005. Comprehensive community building initiatives – ten years later: What we have learnt about the principles guiding the work. New Directions for Youth Development 106, 17–26. doi: 10.1002/yd.115

- Kubisch, AC, Auspos, P, Bown, P & Dewar, T, 2010. Community change initiatives from 1990-2010: Accomplishments and implications for future work. Community Investments 22(1), 8–36.

- Labonne, J & Chase, R, 2009. Who is at the wheel when communities drive development? Evidence from the Philippines. World Development 37(1), 219–31. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.05.006

- Lafferty, CK, & Mahoney, CA, 2003. A Framework for evaluating Comprehensive Community Initiatives. Health Promotion Practice 4(1), 31–44. doi: 10.1177/1524839902238289

- Lyndon, N, Moorthy, R & Selvadurai, S, 2011. Native understanding of participation and empowerment in community development. Journal of Social Sciences 7(4), 643–8. doi: 10.3844/jssp.2011.643.648

- Makhoul, A, & Leviten-Reid, E, 2010. Determining the value of Comprehensive Community Initiatives. The Philanthropist 23(3), 313–8.

- Mason, M, 2010. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 11(3), 1–19.

- Messinger, L, 2004. Comprehensive Community Initiatives: A rural perspective. Social Work 49(4), 535–46. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.4.535

- Murphy-Berman, V, Schone, C & Chambers, JM, 2000. An early stage evaluation model for assessing the effectiveness of Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Three case studies in Nebraska. Evaluation and Program Planning 23, 157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(00)00010-0

- Patton, MQ, 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Platteau, J & Gaspart, F, 2003. The risk of resource misappropriation in community driven development. World Development 31(10), 1687–703. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00138-4

- Porter, G, 2003. NGOs and poverty reduction in a globalizing world: Perspectives from Ghana. Progress in Development Studies 3(2), 131–45. doi: 10.1191/1464993403ps057ra

- Rusinga, O, Chapungu, L, Moyo, P & Stigter, K, 2014. Perceptions of climate change and adaptation to microclimate change and variability among smallholder farmers in Mhakwe Communal Area, Manicaland province, Zimbabwe. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management 7(3), 310–8. doi: 10.4314/ejesm.v7i3.11

- Tashakkori, A & Teddlie, C, 2003. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Walakira, EJ, 2010. Reflective learning in action research: A case on micro-interventions for HIV prevention among the youth in Kakira-Kabembe, Jinja, Uganda. Action Research 8(1), 53–70. doi: 10.1177/1476750309335210

- WK Kellogg Foundation Africa Program, 2005. Expanding on the zoom site process model and integrating knowledge generation and the regional centre's role in the program. Memio, Pretoria.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, 2012. Census report. Government Printing Office, Harare, Zimbabwe.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, 2013. Poverty, income, consumption and expenditure survey, 2011/2012 report. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Harare, Zimbabwe.