ABSTRACT

This article seeks to explain the capacity and limitations of African cities in building resilient infrastructure in the face of climate change. In this article, resilience means the ability of a social or ecological system to absorb disturbances while retaining the same basic structure and ways of functioning, the capacity for self-organisation, and the capacity to adapt to stress and change. To expose the capacity and limitations of African cities in building resilient urban infrastructure, the article presents comparative case studies on contemporary experiences in Harare, Nairobi, Abuja, Cairo and Johannesburg relative to the Latin American and Asian cities where resilient infrastructure practices are in vogue. We conclude that most African cities exhibit critical bottlenecks towards emulating the Asian prototypes. Corruption is among the key explanations for the shortcomings of African cities in the delivery of resilient infrastructure and services. Corruption and non-participatory approaches prevailing in most cities have only courted resistance by citizens in the reimbursement of loans obtained from both international and local financial houses.

1. Introduction

Although the term ‘resilience' has been interpreted differently across various disciplines, it has increasingly gained currency in sustainable development policy circles, programming and thinking around climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction (Alarslan, Citation2009; Trohanis et al., Citation2009). In their appeal for a ‘renaissance' in addressing climate change, Bahadur et al. (Citation2010) suggest that development should be ‘climate resilient’, embedding the synergies of adaptation, disaster risk reduction and the alleviation of intransigent poverty. In the complex, inter-dependent social and ecological systems in which we live, resilience also includes the capacity for transformation when systems cross thresholds. This is ‘social–ecological resilience’ (Folke et al., Citation2010). The term ‘resilience' has been variously deployed as a metaphor for addressing the adverse impacts of climate change in interdisciplinary development and implementation contexts. Some scholars (Bahadur et al., Citation2010) tell us that resilient infrastructure systems feature attributes relating to effective governance and creativity of institutions in enhancing community cohesion. Such attributes are couched in terms of flexibility in decentralised institutions in order to make them responsive to local realities. These institutions should be able to facilitate system-wide learning in translating scientific data on climate change into action plans for policy-makers. Resilience strategies should also be able to capitalise on stakeholder community involvement and appropriate local knowledges in the design and implementation of resilient infrastructure projects (Bahadur et al., Citation2010).

Arrays of historical agency forces are embedded in the bottlenecks of identifying and implementing urban resilient infrastructure in most developing countries. Although this realisation has been noted in recent literature (Dodman, Citation2009; Galderisi, Citation2012) there is a dearth of research that can address the policy implications of the unitary and complex management systems in most African cities. In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, this situation is compounded by the enduring postcolonial policy practices (O'Connor, Citation1983; Kessides, Citation2005) that are not attentive to the diverse, distinctive and rapidly transforming African ordinary cities (Robinson, Citation2002:542). After the decolonisation phase in most of Africa, which triggered the exodus of the European settlers to countries in Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand, most of the residual urban infrastructure has been rendered moribund (Bhorat et al., Citation2002) by decades of neglect (Rakodi, Citation1997:37). Divorced from sustainable urban management practices and desperate for adequate resources, most local governments in sub-Sahara Africa continue to endure little respite in addressing the cumulative infrastructure needs of the bulging resident populations – most of whom are escaping the collapsing rural economies (Thapa, Citation2005; CIBD, Citation2007). The rural migrants bring with them their cultural and livelihood practices which facilitate their entry into the rapidly expanding informal sector now dominating the African city after decimation of their formal economies (Rakodi, Citation1997:343).

Although smart partnerships have become fashionable in addressing urban infrastructure development in Africa, they have produced debatable results (Farlam, Citation2005; SPAID, Citation2007; Lawson, Citation2013). On the contrary, some cities in Asia have made significant in-roads in building resilient urban communities, placing Mumbai in a league of exemplars. Not surprisingly, however, there are still formidable challenges of building and maintaining resilient infrastructure in most African cities. These intercontinental variations have been blamed on differences in governance and institutional frameworks operational in Asian and African cities. Climate change has emerged as one of the greatest cross-border challenges of our time, posing serious threats to urban communities in sub-Saharan Africa in the form of floods, incessant droughts and shifting water bodies. In common with the Asian cities, African cities have not yet fully embraced resilient urban planning practices that articulate the ominous climate changes which have taken centre-stage in world debates. The preponderance of civil disturbances in the midst of stagnating urban economies riddled with widespread urban poverty has left little or no space for governments to be seized with considerations for resilient infrastructure development and climate change in indebted African countries

2. Research scope, design and methodology

This article sets out the debate by illuminating the conceptual framework of resilient infrastructure development. The rest of the discussion deploys comparative case studies on the experiences of resilient infrastructure development in Asia, Latin America and Africa. The conclusion features possible strategies that African cities can engage by drawing on the experiences gained in the Asian and Latin American cities. There is a general tendency of resisting creative ways of financing infrastructure (like value capture and participatory budgeting) due mainly to fear of the unknown (Heimans, Citation2002; Doherty, Citation2003; Goncalves, Citation2009; Smith et al., Citation2014). The key question that this article seeks to address is: how are these cities mediating the ineluctable demands imposed upon them by climate change in providing their communities with resilient infrastructure? To examine this question, the article will interrogate the following aspects:

The role of political influence and corruption in decision-making in the development and utilisation of urban infrastructure in Africa.

Constraints, gaps and opportunities of financing infrastructure.

New challenges of climate change, increasing urban poverty and informalisation in urban infrastructure development and maintenance.

Possible options for promoting resilience in urban infrastructure development.

In examining these aspects, we engage recent scholarships on cities in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Asia where the practices of resilient infrastructure development have taken root to enable us to compare and contrast the distinctive individual experiences in these countries. The experiences in Latin America demonstrate the utility of participatory budgeting and value-addition approaches for articulating community involvement in developing resilient infrastructure (UNISDR, Citation2008). The diversity of bottlenecks in the development of resilient infrastructure in the indebted African economies is brought out by the case studies of Harare, Nairobi, Abuja, Cairo and Johannesburg. The question we now turn to is how has the concept of ‘resilient urban infrastructure’ been framed?

3. Resilience applied to urban infrastructure

The concept of resilient urban infrastructure arguably has different meanings. The United Nations Secretariat of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction portrays resilience as:

The ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions. (UNISDR, Citation2008:2)

Meanwhile ‘urban resilience has been depicted as the extent to which cities can resist, absorb and accommodate shocks through generation of new structures and processes' (Alberti et al., Citation2003:1169). In the context of infrastructure, structural and engineering science, these scholars have framed resilience as the ability of infrastructures to withstand structural shocks brought about by climate change. Resilience seeks to maximise the continued functioning of large-scale infrastructure even when some elements of the infrastructure cannot withstand the severity of the shocks (Alberti et al., Citation2003). A physical infrastructure is considered resilient if it can withstand, adapt and recover from external disruptions, such as the wear and tear from natural forces (severe weather, hurricanes, earthquakes) and man-made forces (densification, extreme overuse, environmental degradation and sabotage).

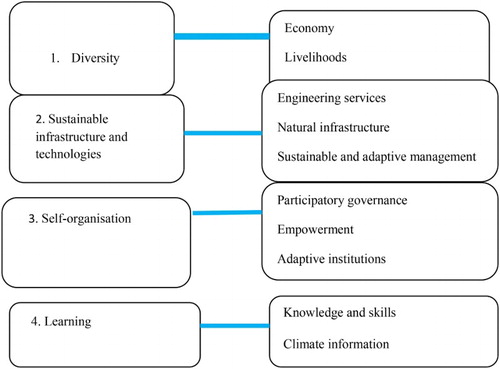

The conceptual framework of ‘resilience', developed by Smith (Citation2011), ascribes to four systemic components; notably, diversity, sustainable infrastructure and technology, self-organisation and learning (see ). Sustainable infrastructure and technology combines engineering services and ‘natural infrastructure’ as well as adaptable and sustainable technologies designed for the management of climate-related vulnerabilities. The outcomes of this component include engineering responses (such as urban drainage or rainfall harvesting) as well as infrastructure management (Smith, Citation2011). The self-organisation component embeds highly adaptive systems engendered through participatory governance and empowerment of people in responsive institutions. Learning is about ensuring that individuals and institutions can use new skills and technologies needed to adapt and make effective use of climate information and adaptation strategies as they become available, and diversity is basically about the economy, livelihoods and nature.

4. Case studies on resilient infrastructure development in Asia, Latin America and Europe

This section presents comparative case studies on the best practices of building resilient infrastructure in selected Asia, European and Latin American cities.

4.1 Resilient urban infrastructure in India

Indian cities have taken bold steps in building resilient infrastructure in moves addressing sustainable development (Energy and Resources Institute, Citation2011). In the Asian region and worldwide, Disaster Risk Reduction has often taken a ‘reactive' approach to relief efforts and rehabilitation in redressing the shocks of natural calamity or disaster (World Bank, Citation2009). The integration of disaster risk management with development interventions sits well alongside preparedness by taking a ‘proactive' approach towards disaster risk reduction.

Many Indian cities have started planning for specific adaptation and mitigation strategies with a view to building long-term resilience in the domain of climate change. The cities of Surat, Indore and Gorakhpur have developed their own specific resilience strategies. The Gorakhpur resilience strategy follows an integrated approach that addresses the institutional, behavioural, social and technical modalities of intervention (Energy and Resources Institute, Citation2011). The strategy emphasises effective implementation of master plans while building in climate concerns into these plans that are statutory documents meant to guide the growth and development of the city. The strategy advocates utilising targeted interventions that build knowledge, provide demonstrated examples to assist development, and build the capacity of organisations.

The Surat and Indore resilience strategies are structured around four main principles; namely, building on current and planned initiatives; demonstrating resilience-building projects to leverage further action; multi-sectoral information generation, and shelf of projects; and building synergies between national and local institutions (Rajasekar et al., Citation2012:5). These Indian cities reify the need for mainstreaming their resilience strategies into city development processes and synergies at national and local levels in order to leverage funding in the implementation of their strategies (Energy and Resources Institute, Citation2011). These cities are committed to building resilient communities in a more comprehensive manner. The approaches adopted by the cities in India are not ad hoc despite resource constraints.

The incorporation of resilient infrastructure development strategies in statutory plans in India is a mandatory requirement. This requirement is enforceable in terms of the country's town and country planning legislation and development control regulations, building bye-laws, district planning manual of the Planning Commission, national building codes and Urban Development Plan Formulation and Implementation guidelines (Energy and Resources Institute, Citation2011). However, enforcement of this statutory tool-kit in the implementation of urban resilience projects has been stalled by an array of constraints. These constraints commonly relate to financial resource allocation systems; in particular, the lack of fiscal autonomy of city governments that have to rely on the discretion of central and federal state governments in disbursing funds to city governments.

The city of Mumbai has invested considerable resources in making the city more responsive to the terminal shocks and stresses of climate change. The city provides an exemplar of massive land reclamation from the sea to address the demands for space by the burgeoning population and infrastructure developments. Apart from the climatic change shocks accustomed to the city, the encroaching ecological footprint of Mumbai threatens the marine ecosystems and human habitats (Srivastava, Citation2002) due to overflooding. Hence, it is important to develop urban resilience plans considering the multiple stresses faced by this coastal mega-city (Energy and Resources Institute, Citation2009). This scenario presents Mumbai with the daunting challenges of providing its adversely affected residents with requisite services such as potable water, the disposal and management of waste and education while the city is seized with desperate appeals for resilient infrastructure remedies. Arguably, this calls for a systems modelling of the projected land-use planning interventions, infrastructure packages, communication systems, demographic trends and governance in crafting a resilient infrastructure portfolio.

4.2 Resilient infrastructure in Sendai, Japan

Japanese cities are more exposed to external environmental shocks in the form of tsunamis, earthquakes and other natural disasters (Lassa, Citation2011). However, Japanese cities are proprietors of the most resilient infrastructure assets in the Asian Pacific region (City of Sendai, Citation2013). This indicates the highest level of commitment among the different city authorities on the Japanese islands. Investing in resilient infrastructure is very vital in protecting cities from external shocks, but investing in soft infrastructure is equally important.

The municipality of Sendai has embraced the concept of human resilience that focuses on social, cultural and education competencies in building resilient cities. This city has also made significant efforts in building resilient infrastructure assets that can withstand external shocks wrought by the customary tsunamis and earthquakes. The city has fortified its infrastructure base after years of repeated disasters, propelling it into the top league of cities with the most resilient infrastructure in Japan (City of Sendai, Citation2013). The building of resilient infrastructure was done in a more decentralised way, where the local government was responsible for building its own infrastructural assets including telecommunications, roads and railways. The decentralised nature of infrastructure development paid dividends by accelerating the implementation process through improved governance and insulating against corrupt practices in service delivery. In continued efforts to build resilient urban infrastructures, Japanese cities collaborate with private-sector players through the formation of public–private partnerships.

4.3 Resilient urban infrastructure in Latin America

The communities of most Latin American cities experience a wide range of service delivery problems concerning the provision of shelter, transport, education and health, housing, infrastructure and adequate public relief services in the event of earthquakes, cyclones and heavy floods (UNISDR, Citation2008). Despite these perennial problems, Latin America has reportedly made significant progress in the construction of resilient infrastructure facilities (KPMG, Citation2013). Many Latin American cities such as Mexico, Sao Paulo and Paraguay have made in-roads in building resilient infrastructure through integrated urban development plans. In particular, Latin American countries demonstrate some successful experiences in preventive resettlement and settlement up-grading that is reducing poverty by creating employment, providing professional training opportunities and improving land rights (UNISDR, Citation2008).

In 2012, Lima City Council in Peru launched a settlement upgrading initiative called the My Neighbourhood Programme (Programa Barrio Mio) which aims to improve the quality of life of Peruvians living in hillside settlements in the capital city (UNISDR, Citation2008). With a $30 million budget, the programme combines risk mitigation and disaster prevention activities, such as reforestation and urban reorganisation, with the construction of civil infrastructure like stairways and defence walls, and social infrastructure such as sports, cultural and community centres. The programme also includes disaster response training for residents. Since the initiative was only launched in 2012, no results have yet been documented, although the planning, funding and operationalisation processes do provide some interesting lessons for other countries. The critical success factors for the initiatives in Latin America include strengthening livelihoods (natural resource management; provision of basic services; infrastructure development), good urban governance (regulatory frameworks; planning for growth), financial tools (credits and insurance), ecosystem management (protected areas; payments for ecosystem services) and community-based risk reduction approaches

4.4 Resilient urban infrastructure in Europe

The European Commission has published guidelines on resilient infrastructure building which European cities have to comply with in order to boost their resilience (Galderisi, Citation2012). The guidelines provide a range of measures classified in the White Paper entitled ‘Adapting to Climate Change: Towards a European Framework for Action' (EC, Citation2009). According to this White Paper:

‘grey infrastructure' is related to physical interventions or construction measures and using engineering services to make buildings and infrastructure essential for the social and economic well-being of society more capable of withstanding extreme events;

‘green infrastructure' is devoted to the increase of ecosystems resilience and to the reduction of biodiversity loss, waste of water and degradation of ecosystem and

‘soft measures' consist of policies, plans, programs and procedures implemented for achieving behavioral changes that can be very relevant in contexts characterised by high levels of uncertainty, due to the fact that they contribute to increase adaptive capacity. (UNECE, Citation2009:32)

Therefore, cities seem to play a crucial role in all of the European strategies for tackling climate change, in terms of mitigation being relevant to all measures related to the sectors of power, transport and built environment, and of adaption measures, specifically tailored for urban areas.

Having provided a reflection on the best practices in building resilient infrastructure, we now turn to case studies on the building of resilient infrastructure in the African cities of Harare, Abuja, Johannesburg, Nairobi and Cairo. These cities have been purposefully selected due to their peculiarities and differences in the practice of infrastructure construction.

5. Case studies on African cities

Urban settlements have been widespread in Africa for centuries. However, it was in the late nineteenth century when most African cities were conceived as ‘postcolonial cities’ since they emerged during the colonial era. These cities were designed to meet the specific demands of the European minority settlers, most of whom relocated to other continents following episodic decolonisation of Africa in the last half-century. Trapped in a confluence of rapid urbanisation, debilitating economic reforms and dwindling resources, most African cities grapple with the intractable challenges of providing and maintaining adequate infrastructure for their seamless populations.

5.1 Harare, Zimbabwe

Harare is the capital city of Zimbabwe. The city experienced an annual population growth rate of 5% throughout the 1980s. Despite the ascendancy of resilient infrastructure in the mitigation of climate change shocks affecting the liveability of the city, the continued political strife undermining efficient service delivery in Harare city for years now seems to have trivialised the urgency of the matter. The deterioration in the delivery of infrastructure and related services in Zimbabwe's primate city has been attributed to a combination of the poor institutional capacity of the city and its tottering economy (African Development Group, Citation2011). The local media is frequently awash with news about the rampant cases of corruption in the management of resources ear-marked for service delivery in the deeply polarised city (Dube, Citation2011). Funding set aside for the building of water treatment works is sometimes diverted to private use by officials in charge of the projects (Bland, Citation2010; Mapira, Citation2011) under the full glare of the serious financial challenges daunting the city. Added to this raft of challenges is the lack of transparency and accountability in the governance of city finances. The deepening urban poverty combined with the runaway unemployment rate has served to trigger the informalisation of land uses and service delivery, thereby placing the city-wide development of Harare under siege.

In theory, good planning and regulatory frameworks are critical in building urban resilience. However, there are shortfalls in local government and regulatory frameworks in Harare. The institutional basis for municipal adaptation is very weak in Harare. Large sections of the urban population and the urban workforce are not served by a comparable web of institutions, infrastructure, services and development control regulations (Dodman, Citation2009). It is common for between a third and a half of the entire urban population to be living in illegal settlements formed outside any land-use plan. These illegal land uses include squatter or slum settlements and illegal land sub-divisions (Dodman, Citation2009) mainly in the interstitial spaces of the city and satellite towns of Epworth and Chitungwiza, and the make-shift peri-urban areas of Caldonia and Hopley.

The chaotic land occupations (code named ‘jambanja’, vernacular for chaotic violent land invasions) on the fringes of all major towns and cities in Zimbabwe in 2000 triggered the mushrooming of informal settlements – mainly driven by housing cooperatives led by veterans from the country's war of independence from Britain. Since the land occupations were chaotic it is unsurprising that the make-shift settlements developed without prior planning permission, let alone without any form of rudimentary infrastructure in the form of roads, water and sewerage systems as required by the country's planning law. The product of this is not only the loss of resilient vibrant ecoystems in the greenbelts of most cities in the country but also frequent outbreaks of epidemics including cholera and typhoid as the desperate new settlers are forced to rely on water drawn from polluted rivers and wells for household uses.

5.2 Nairobi, Kenya

The rapid population growth of Nairobi continues to exert excessive pressure on the existing infrastructure (Asoka et al., Citation2013). The City of Nairobi has an average annual growth rate of about 2.8% (UNEP, Citation2007). If this trend persists, the growing East African regional hub desperately needs an expanded infrastructure and services base to withstand any foreseeable climatic shocks. Meanwhile, the continued deterioration of infrastructure in Nairobi, especially the road network, has been noted. In a study conducted by Asoka et al. in Citation2013, the Nairobi City Council indicated that it has become expensive to maintain the road infrastructure as a result of the burgeoning population of the city. The carriageways are continuously being eroded due to poor construction of embankments. A number of projects have also been undertaken by the City of Nairobi to restore infrastructure that had been destroyed by climate hazards. The City Council of Nairobi initiated road re-surfacing and maintenance projects in many parts of the city in order to address the impacts of the heavy El Niño rains of 1989 and the early 1990s that damaged roads in many parts of the country (Asoka et al., Citation2013). The projects faced implementation challenges as evidenced by the road infrastructure that continues to deteriorate.

Nabutola (Citation2006) points out that there are various infrastructure challenges in the Kenyan economy. Some of the challenges relate to financing of urban infrastructure projects, and include strain on central and local government funding due largely to insufficient public funds and misappropriation by relevant authorities. This state of affairs is further compounded by the lack of technical know-how essential for the design and implementation of resilient infrastructure to service the mounting city requirements (Nabutola, Citation2006). Nairobi is associated with perhaps the largest slum compound of Kibera – a time bomb of a possible inferno should installation of protective infrastructure continue to bypass the densely built-up and overcrowded sprawling enclave (Opiyo, Citation2009).

5.3 Abuja, Nigeria

Abuja is the federal capital of Nigeria. The city has experienced rapid population growth, pegged at 40.2% (Jinadu, Citation2004). This rapid urban population growth exerts too much pressure on urban infrastructure and services (Jinadu, Citation2004). Abuja presents a case of untapped potential for employment creation in forging the development of resilient infrastructure. Despite the importance of urban infrastructure, the governments at both federal and state level have paid little or no attention to infrastructure development and provision in the Nigerian capital city (Onyenechere, Citation2010). Poor town planning, bad governance and corruption among other factors seem to be conspiring against the building of resilient urban infrastructure in Abuja (Usman & Tunde, Citation2010). The building of infrastructure is also hindered by the negative attitudes of the appointed supervisors to monitor the projects (Usman & Tunde, Citation2010). Such factors work against the building of sustainable urban communities. The abundant resources of Nigeria can be harnessed to improve the state of infrastructure provisioning in the cities.

5.4 Cairo, Egypt

The mega-city of Cairo has experienced rapid population growth trends. Cairo has a population of about 14 million and is expected to reach 24 million by 2022 (El Kouedi & Madbouly, Citation2007). Disturbingly, most of the settlements are located in high-risk zones, where there is lack of disaster-resilient construction, infrastructure and basic services (Schafer, Citation2013). About 50% of the urban population also live in informal settlements. The capacity of Cairo municipality to provide resilient infrastructure is arguably questionable. There are several institutional gaps and challenges in the Cairo city, which include the lack of technical expertise together with human resources, financial and logistical capacity essential for the construction and maintenance of infrastructure. This is worsened by the poor coordination between regional, national and urban authorities, which militates against the effective and efficient provision of infrastructure, particularly in disaster-prone settlements.

5.5 Johannesburg, South Africa

The African world city of Johannesburg, experiencing an annual growth rate of 3.16%, is the most populous in Southern Africa (STATS-SA, Citation2007). In recent years, the existing infrastructure of the expanding city-region has experienced spasms of flush flooding and damage to water and sanitation infrastructure including telecommunications. The City of Johannesburg comprises 180 informal settlements across all regions of the City (Housing Development Agency, Citation2012). This urban development scenario is a threat to sustainability. The city region is prone to significant climate change-related threats, which continue to hamper efforts in the installation of resilient urban infrastructures. These policy-related constraints include limited technical capacity, the lack of political commitment and dwindling resources (Phalatse, Citation2011).

6. Discussion

The outcomes of building resilient infrastructures in the poor and heavily indebted countries of Africa depend on a constellation of factors – not least the technological creativeness of implementing agencies and the political incentives facing political leaders in the cities of these countries. This article has spelt out some of the policy implications of this observation in the context of the challenges confronting attempts at developing resilient infrastructure as revealed by experiences in sub-Saharan African cities. The article draws heavily on the comparative case studies of cities in Asia, Latin America and Africa. Admittedly, the African cities badly need to engage the processes of political, economic and governance transformation by generating synergies with other cities to enable them forge the emerging institutional ‘best practices’ where resilient infrastructure building practices are paying dividends.

The article notes that politics and power games assume a prominent role in providing an atmosphere where both adverse and promotional factors to infrastructure development come into play. The enduring presence of corrupt practices in the allocation and disbursement of political incentives partially explains why most African cities sometimes fail to deliver – let alone maintain – the desperately needed infrastructures. At stake here are the majority urban poor and marginalised whose right to the city in the construction and maintenance of resilient infrastructure remains peripheral to city-wide development practice. Although most cities are statutorily empowered to access loans to finance infrastructure, the corrupt tendencies of pilfering by some officials added to non-involvement of beneficiary communities have only fuelled citizen resistance in the repayment of loans sourced from funding agencies. Citizens are often reluctant to pay for services that they may not be receiving – the cases in point are frequent power outages and water interruptions in Harare. In recent times, some of the Asian coastal cities and slum areas have gained notoriety for massive loss of human lives and damage to property due to devastating tsunamis and floods induced by global warming. The natural disasters and loss of life seem to have conspired with the impoverishment of the adversely affected communities held ransom by politicians for political gain through patronage and clientilism.

7. Conclusions

The discussion concludes that interrogating the development of resilient urban infrastructure in the crucible of climate change is essential for promoting sustainable communities in the rapidly urbanising and poor countries of the Global South. However, the currency of building resilient infrastructure in the marginalised and poor African cities has been protracted by the lack of political will for want of political incentives, inept institutions, corruption and the paucity of implementing resources. On the Asian continent – thanks to the upsurge in economic growth in recent times – most cities have registered successful investments in the development of resilient infrastructure networks, earning these cities a competitive edge in the globalising arena. We recognise that the outcomes of developing resilient infrastructures in the African cities are shaped considerably by the political fortunes facing political leaders at the expense of domestic needs (Lemanski, Citation2007). This article has spelt out some of the implications of this observation in the context of the challenges facing the cities in sub-Saharan Africa. Inspired by the in-roads that cities in Asia and Latin America have made in the development of resilient infrastructure, the African cities badly need to embark on the processes of economic discipline and sustainable governance in collaboration with the approaches that have gained currency in cities which have evidently taken the lead. Considering Smith (Citation2011), participatory governance and the empowerment of locals are critical building blocks of resilient communities – mobilised through skills training programmes for community members. Such programmes can furnish platforms of dialogue between officials and locals on resource ownership and accountability, sharing local knowledge in facing climate change effects, networking for the enforcement of environmental laws. Through the local press, the Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Commission has appealed to residents to report acts of electricity infrastructure vandalism to the authorities.

We recommend the adoption of infrastructure financing mechanisms that have worked in other regions by adapting them to the diverse and distinctive everyday needs of the African city. We also privilege a sound governance framework whose building blocks will include trust, transparency and accountability. Such frameworks envisage decentralised organisational structures and policies that are responsive to local reality and complexity. There is an urgent need for cities to design and implement infrastructure that can withstand external shocks and stress. This can help urban communities to become sustainable, especially in this era of urban climate change that tends to greatly affect informal settlements. The building of resilient urban infrastructure should not just be an inventory of prescriptive interventions, but a process of investing in the building of indigenous knowledge, institutions and community ownership (Phalatse, Citation2011).

One of the major challenges for cities facing rapid population growth is the maintenance of environmental sustainability (Galderisi, Citation2012). Some of the factors that can make African cities more resilient include the presence of robust urban infrastructure, good governance and legal framework, participatory approaches for multi-stakeholder interactions, and replicability of best practices. Best practices can offer a platform for other cities to learn from. It is also critical to point out that resilience is multi-sectoral: policies need to be integrated within on-going decision-making and planning processes in critical sectors, resilience is an incremental process and, as such, planning should emphasise mechanisms for on-going learning, evaluation and adjustment of strategies based on observed impacts of climate changes. In building resilient urban communities, authorities should not only be concerned with ‘hard infrastructure projects', but also software can help in improving or strengthening the adaptive capacity of populations and sectors. In addition, urban resilience should be conceptualised in line with local and regional developmental priorities, and focus on the most vulnerable sectors, and resilience planning should involve all stakeholder groups. It is a multi-sectoral approach, operating at various levels of institutional set-up. Mainstreaming resilience planning needs to be guided by policies and legislative framework to help integration with development activities at all levels.

Dodman (Citation2009) suggests a number of strategies that can be engaged in promoting urban resilience in cities. He raises the question of what can be done to improve resilience in cities of developing countries. Resilience will require improving urban infrastructure, creating more effective and pro-poor structures of governance, and building the capacity of individuals and communities to address these new challenges and move beyond them (Dodman, 2009). Urban resilience can also be facilitated through the adoption of pro-poor strategies that enable individuals and households to develop sustainable and resilient livelihoods. Indeed, having a solid economic base is one of the main ways to help households cope with the shocks and stresses due to climate-related hazards. The active involvement of all local stakeholders and supportive national governments informed by research that is attentive to the diversity and distinctive African cities cannot be emphasised for the fruition of resilient infrastructural development in these peripheral cities. To this end, central governments – as the leading architects of the enabling legislative, financial and institutional policy practices shaping investment efforts in the terrain of infrastructure development – should be seized with creative ways of engaging local authorities, the private sector, civil society and local communities towards addressing climate-change-related initiatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- African Development Group, 2011. Infrastructure and growth in Zimbabwe. An action plan for sustained strong economic growth. African Development Bank Group, Tunis. http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Generic-Documents/Zimbabwe%20Report_Book22.pdf Accessed 13 April 2014.

- Alarslan, E, 2009. Disaster resilient urban settlements, Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Faculty of Spatial Planning of Technical, University of Dortmund. http://d-nb.info/1000246566/34 Accessed 12 April 2014.

- Alberti, M, Marzluff, J, Shulenberger, E, Bradley, G, Ryan, C & Zumbrunnen, C, 2003. Integrating humans into ecology: Opportunities and challenges for studying urban ecosystems. BioScience 53(12), 1169–79. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[1169:IHIEOA]2.0.CO;2

- Asoka, GW, Thuo, AD & Thuo, MM, 2013. Effects of population growth on urban infrastructure and services: A case of Eastleigh neighborhood Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Anthropology and Archaeology 1(1), 41–56. http://aripd.org/journals/jaa/Vol_1_No_1_June_2013/4.pdf Accessed 9 April 2014.

- Bahadur, AV, Ibrahim, M & Tanner, T, 2010. The resilience renaissance? unpacking of resilience for tackling climate change and disasters. Strengthening Climate Resilience Discussion Paper 1. London: Institute of Development Studies.

- Bhorat, H, Meyer, JB & Mlatsheni, C, 2002. Skilled labour MIGRATION from developing countries: Study on South and Southern Africa. International Migration Papers. International Labour Office, Geneva.

- Bland, G, 2010. ‘Zimbabwe in transition: What about the local level?' Research Triangle Institute. http://www.rti.org/pubs/op-0003-1009-bland.pdf Accessed 15 April 2014.

- CIBD (Construction Industry Development Board), 2007. The state of municipal infrastructure in South Africa and its operation and maintenance: An overview. http//www.cidb.org.za/Documents/KC/cidb_Publications/Ind_Reps_Other/ind_reps_state_of_municipal_infrastructure.pdf Accessed 1 September 2014.

- City of Sendai, 2013. Rebuilding for resilience. Fortifying infrastructure to withstand disaster. City of Sendai, Japan.

- Dodman, D, 2009. Building urban resilience in the least developed countries. International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

- Doherty, M, 2003. Funding public transport development through land value capture programs. http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/doherty-matthew_land-value-capture.pdf Accessed 15 April 2014.

- Dube, T, 2011. Systemic corruption in public enterprises in the harare metropolitan area: A case study. unpublished master of public administration Thesis, University Of South Africa, Pretoria.

- EC (European Commission), 2009. White paper. Adapting to climate change: Towards a European framework for action, Brussels). http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2009:0147:FIN:EN:PDF Accessed 1 September 2014.

- El Kouedi, H & Madbouly, M, 2007. Tackling the shelter challenge of cities. Thinking it through together. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Energy and Resources Institute, 2009. An exploration of sustainability in the provision of urban basic services. Energy and Resources Institute Press, New Delhi.

- Energy and Resources Institute, 2011. Mainstreaming urban resilience planning in Indian cities: A policy perspective. ERI (Energy and Resources Institute), Delhi.

- Farlam, P, 2005. Working together: Assessing public–private partnerships in Africa, Nepad Policy Focus Report No. 2, South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA). Royal Netherlands Embassy, Pretoria.

- Folke, C, Carpenter, SR, Walker, B, Scheffer, M, Chapin, T & Rockström, J, 2010. Resilient thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society 15(4), 20. http://www-ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/ Accessed 2 May 2014.

- Galderisi, A, 2012. The resilient city. Enhancing urban resilience in the face of climate change. Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment 5(2), 69–87.

- Goncalves, S, 2009. Power to the people: The effects of participatory budgeting on municipal expenditures and infant mortality in Brazil. http://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/Goncalves-Effects_of_Participatory_Budgeting-Brazil-2.pdf Accessed 15 April 2014.

- Heimans, J, 2002. Strengthening participation in public expenditure management: Policy recommendations for key Stakeholders, Policy Brief No.22, OECD Development Centre.

- Housing Development Agency, 2012. Gauteng informal settlements status. Gauteng Research Report. Johannesburg.

- Jinadu, AM, 2004. Urban expansion and physical development problem in Ab uja: implications for the national urban development policy. Journal of the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners. XVII: 15–29.

- Kessides, C, 2005. The urban transition in sub-saharan Africa: Implications for economic growth and poverty reduction. Urban Development Unit, The World Bank.

- KPMG, 2013. Resilience: With a special feature on Latin America's infrastructure market, Insight: The global infrastructure magazine/Issue No. 5. http://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/insight-magazine/Documents/insight-resilience.pdf Accessed 19 April 2014.

- Lassa, JA, 2011. Japan's resilience to tsunamis and the lessons for Japan and the world: An early observation. http://www.zef.de/module/register/media/b4d0_Japantsunami%20resilience31mar2011.pdf Accessed 28 April 2014.

- Lawson, ML, 2013. Foreign Assistance: Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs). http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41880.pdf Accessed 19 April 2014.

- Lemanski, C, 2007. Global cities in the South: Deepening social and spatial polarisation in Cape Town. Cities 24(6), 448–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2007.01.011

- Mapira, J, 2011. Urban governance and mismanagement: An environmental crisis in Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 13(6,2), 258–67.

- Nabutola, W, 2006. Financing urban infrastructure development and maintenance, with particular reference to Nairobi. Shaping the Change. XXIII FIG Congress. Munich.

- O'Connor, A, 1983. The African city. Hutchinson, London.

- Onyenechere, EC, 2010. Climate change and spatial planning concerns in Nigeria: Remedial measures for more effective response. Journal of Human Ecology 32(3), 137–48.

- Opiyo, R, 2009. Metropolitan planning and climate change in Nairobi: How much room to manouvre? Fifth Urban Research symposium, Nairobi.

- Phalatse, L, 2011. Vulnerability assessment and adaptation planning for the city of johannesburg. Resilient Cities Congress, Bonn, Germany.

- Rajasekar, U, Bhat, GK & Karanth, A, 2012. Tale of two cities: Developing city resilience strategies under climate change scenarios for Indore and Surat, India. http://acccrn.net/sites/default/files/publication/attach/TaleofTwoCities_TARU_0.pdf Accessed 17 November 2015.

- Rakodi, C (Ed.), 1997. The urban challenge in Africa: Growth and management of its large cities. United Nations University Press, New York.

- Robinson, J, 2002. Global and world cities: A view from off the map. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26(3), 531–54. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00397

- Schafer, K, 2013. Urbanisation and Urban risks in the Arab Region. 1st Arab region Conference for Disaster risk Reducation 19-23 March. Aqaba. UN-Habitat, Jordan.

- Smith, M, 2011. Combining the what and how of building climate resilience: Water ecosystems and infrastructure. In Waughray, D (Ed.), Water security: The water-food-energy-climate nexus (pp. 201–3). Island Press, Washington, DC.

- Smith, JJ & Gihring TA with Litman, T, 2014. Financing transit systems through value capture: An annotated bibliography. Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

- Srivastava, S, 2002. Dynamics of coastal regimes. In the National Seminar on Creeks, Estuaries and Mangroves Pollution and Conservation, Thane, India, 28-30 November 2002, BN Bandodkar College of Science, Thane.

- SPAID (Support Programme for Accelerated Infrastructure Development), 2007. Key challenges to public private partnerships in South Africa. Business Trust and the Presidency of the Government of South Africa, Pretoria.

- STATS-SA (Statistics South Africa), 2007. Community survey, 2007 basic results: Municipalities. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03011/P030112007.pdf Accessed 15 April 2014.

- Thapa, GB, 2005. Integrated watershed management: Some basic concepts and issues. Encylopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS). http://www.eolss.net/sample-chapters/c14/e1-18-04-05.pdf Accessed 17 April 2014.

- Trohanis, Z, Shah F & Ranghieri F, 2009. Building climate and disaster resilience into city planning and management processes. Paper presented at the Fifth Urban Research Symposium 2009. http://www.preventionweb.net/files/12506_buildingclimateandEN.pdf Accessed 15 April 2014.

- UNECE (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe), 2009. Guidance on water and adaptation to climate change. United Nations, New York.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2007. City of Nairobi environment outlook. http://www.unep.org Accessed 6 July 2015.

- UNISDR (United Nations Secretariat of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction), 2008. Linking disaster risk reduction and poverty reduction good practices and lessons learned. United Nations, Secretariat of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Geneva.

- Usman, BA & Tunde, MA, 2010. Climate change challenges in Nigeria: Planning for climate resilient cities. Environmental Issues 3(1), 101–10.

- World Bank, 2009. Do natural disasters affect human capital? An assessment based on existing empirical evidence. World Bank, Washington, DC.