ABSTRACT

Broiler chicken production is an important livelihood option for urban households in Zimbabwe. A study was carried out to document the technical, demographic and socio-economic parameters characterising the production of broilers in an urban area of Zimbabwe. Findings showed that producers have quite diverse livelihoods and broiler production is not restricted to a survival strategy for the urban poor with no livelihood alternatives, but mostly involved the more privileged. Access to start-up capital and property ownership were pre-requisites for the business. Broiler units were small-scale, informal, backyard businesses dominated by women. Flock sizes averaged 398 (range 25–3500) birds per cycle. However, 79% of the producers kept at most 200 birds per cycle. The mean stocking density was 9.5 birds/m2 and reported mortality averaged 7.4%. Respondents have ad hoc marketing arrangements, and face constraints with regard to lack of sectoral support, shortage of capital, prohibitive council by-laws, market access and disease. Poultry production is therefore an important livelihood and business option in the urban and peri-urban area studied.

1. Introduction

The current global revolution in livestock production is dominated by intensive poultry and pig rearing. Globally, the poultry industry is the fastest growing agricultural sub-sector, driven by a combination of push and pull factors. Basic factors driving global demand for animal protein (particularly chicken) are increased earning power against a background of falling prices; urbanisation and the resultant shift in consumption patterns; and rapid population growth. On the supply side, growth of the poultry industry is due to improvements in breeding, nutrition, production and processing technologies, increasing the efficiency of chicken production (Rushton, Citation2009; Penz & Bruno, Citation2011). Poultry are mostly raised under intensive systems that can easily adopt technologies to improve the efficiency of converting feed into meat without the need for vast tracts of scarce land. For instance, between 2010 and 2030 chicken is projected to lead an increase in animal protein production with a growth forecast of more than 57% globally, making it the dominant meat source by end of the period (Roppa, Citation2012). The current global livestock revolution therefore has huge potential as a means for millions of poor people to join the market economy.

Increasing urbanisation and population growth is putting a strain on urban food supply systems, and household food and nutrition security. Urban centres are failing to create sufficient formal employment opportunities for all, making urban inhabitants vulnerable to income poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition. To compound this, costs of food supply to the urban areas based on rural production and imports are ever rising, yet poor urban inhabitants lack sufficient cash to buy the food at high prices. To enhance resilience of their livelihoods, urban households are struggling through a variety of coping strategies, including urban agriculture (Kutiwa et al., Citation2010).

Broiler chickens are assuming an important role in the livelihoods of urban and peri-urban households in Zimbabwe. A desk study by the Livestock and Meat Advisory Council in 2013 revealed that 70% of all commercial day-old chicks produced in Zimbabwe are broilers, and emerging, relatively small-scale informal producers account for the bulk (65%) of production. Most (73%) of these producers reside in urban and peri-urban areas, and keep small flocks. A survey by Kutiwa et al. (Citation2010) in Harare's low-income suburbs revealed that chicken production is the only urban agriculture activity with a positive significant effect on household cash income status and dietary diversity for the benefit of the majority of poor urban households.

Chicken production also stimulates local economic development of urban centres through the development of related micro-enterprises wholly or partly responsible for the provision of inputs and processing, packaging and marketing of outputs as well as provision of services to the sector (LMAC, Citation2013). In addition, urban broiler production may contribute to poverty alleviation and socio-economic inclusion of vulnerable groups such as the urban poor, women, the disabled, orphans and the unemployed to provide them with a decent livelihood. Lastly, fresh meat and eggs are availed in the city, thus complementing rural production in the food supply system.

Despite significant contribution of the small-scale sector chicken meat supply, there is no documented information to guide policy interventions in poultry development in Zimbabwe and coping strategies to the externalities related to the production of poultry in urban populated environments (Faranisi, Citation2010; ZPA, Citation2011). This study therefore had as its aim the documentation of technical, demographic and socio-economic parameters characterising the commercial production of broilers in urban and peri-urban Marondera, Zimbabwe. The study addressed four key research questions as follows:

Who are the producers (demographic and socio-economic factors) of broilers in urban areas?

How important is the urban poultry sector to household income, women and youth employment, and economic empowerment?

What management practices and performance parameters characterise existence of broiler units in urban areas?

What are the major constraints and priority needs in sectoral development assistance in the study area?

2. Methodology

The study was conducted in February 2013 in Marondera, a town of about 62 000 residents in Mashonaland East Province of Zimbabwe (ZIMSTAT, Citation2013). The town is 72 km south-east of the capital, Harare, at 18°11′S latitude and 31°28′E longitude, and stands at an altitude of 1670 m above sea level. Selection of respondents was done in a stepwise manner. Firstly, the choice of Marondera town as the study site was based on convenience. Suburbs within the town were first clustered according to residential stand sizes as defined by the municipality and then sampling suburbs were selected at random from each cluster. Respondents were selected from Dombotombo and Cherutombo (high density, 175–400 m2); Rusike Park and Morningside (medium density, 401–1500 m2); Winston and Paradise Park (low density, 1500–5000 m2); and Arthurstone and Grasslands (plot >5000 m2). Due to absence of a sampling frame for urban and peri-urban chicken producers, 55 households were identified for the study using the exponential non-discriminative snowball sampling technique. Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling technique suitable for use when the population members are not readily identifiable and the population size is unknown at the start of the research. Urban livestock farming is a legal grey area in Zimbabwe so it is difficult to obtain a sampling frame on which probability sampling would be applied. It was therefore considered easier in this study to use snowball sampling because this allows the researchers to discover the hidden poultry producers. Snowballing involved identifying a few initial members of the study population, collecting data from them, using those existing study subjects or ordinary community members as informants to identify other poultry producers that they knew about, and repeating the process until no new producers could be discovered. A pretested, structured questionnaire was administered to these households to extract information on their demographics and socio-economic situation, flock sizes, management practices, technical performance parameters, access to support services and priority needs in poultry-sector development assistance. An observation approach was used on housing systems information and stocking density calculations.

Data analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package of the Social Sciences Version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Citation2007). Data analysis involved descriptive statistics, frequencies and cross-tabulations to obtain an indication of the relationships of the variables in the analysis. Kruskal–Wallis and chi-square tests were performed to investigate the degree of variability across the different household locations in terms of flock sizes, stocking densities, mortality rates and marketing aspects.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Respondent social and demographic factors

The study revealed that all of the respondents had received formal education and educational levels were quite diverse: 10% had primary education, 41% had secondary education, 35% had college education and 12% had gone to university. The results also showed that the majority of the respondents were married (78%), with the rest (22%) being widowed, divorced or never married. Respondents included women (57%), the disabled (2%) and pensioners (4%), showing that urban poultry can be an important activity for the economic inclusion of socially disadvantaged members of society. These results are consistent with the assertion by Ambrose-Oji (Citation2009) that there is enormous variation in sub-Saharan Africa in terms of the social status, age groups, educational background and gender of those involved in urban agriculture activities.

Sixty-seven per cent of the producers owned the properties on which they produced the broilers, while 19% rented or used employer-provided housing (14%). All sample households had direct entitlement to the use of space for chicken production purposes through property ownership or occupation of a full house (owner not on same property) or cottage house (even when the owner occupied same property). Kutiwa et al. (Citation2010) also observed that property ownership is a pre-requisite for on-plot urban agriculture activities.

Business start-up was largely self-financed through personal and household savings as well as sale of assets for 68% of the households interviewed. Other sources of capital included private borrowing in 14% of the households; remittances from family and friends recorded in 6% and 14% mentioned a combination of sources. As highlighted by Babubi et al. (Citation2004), respondents reported a shortage of capital as a major challenge limiting the size of their operations.

Chicken production was carried out as a business activity to generate cash income for the sampled households. Other reasons for venturing into broilers included cheaper household meat supply, diversification of household income sources, interest or idealism and integration with related operations. Eighty-eight per cent of the households spent cash from broiler sales on household expenses; 82% revolved it back into the business; 40% paid children's school fees; 26% purchased assets; 26% made investments in other enterprises; and 18% purchased building materials. Therefore, payment for immediate household expenses such as food, clothing, bills and school fees was the most important use of the broiler income. Broiler production thereby contributes directly and indirectly to food security, education and social welfare.

Respondents were also asked to state the five major household sources of income and then rank them according to contribution to total household income. The sources mentioned included broiler sales (all households), formal employment, other agricultural activities, remittances, informal trading and formal business. Each income source mentioned was ranked, with rank 1 being the most important and rank 5 being the least important income source. To calculate the overall rank for each income source, weights were assigned to each rank in declining order such that rank 1 had the greatest weight of 5, rank 2 was given a weight of 4 and rank 5 had the least weight of 1. The overall weighted index for each income source was then computed using the formula:

where WI is the overall weighted index for income source, i is the rank position (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and freq.(1i) is the number of times the income source was mentioned in rank i.

Overall, in terms of contribution to household income, poultry production (frequency of 100%) was the highest ranked, formal employment (58%) was ranked second, while rental and remittance income (53%) was ranked as the third most important income source. Informal trading, with a 40% frequency, was ranked as the fourth most important income source followed by small formal business (29%). A significant number of respondents (43%) also obtained income from farming activities both on plots and on farms around town (). However, farming activities other than poultry were ranked as the least important income source for respondent households in the study area.

Table 1. Frequency and ranking of income sources for respondent broiler producer households in urban and peri-urban Marondera (n = 55).

The Pearson chi-square test was significant (p < 0.05) for the frequencies of formal employment, farming activities and formal business as sources of income across household location (, ). Besides poultry being a source of income in all households, formal employment was the second most important income source in medium and low-density areas and least important in the low-income, high-density areas. Informal trading was the second most important income source in high-density areas followed by farming activities, and the third most important income source in the medium-density areas after formal employment. The percentage of respondents deriving income from formal business was generally low, and only those who reported this income source were from the higher-income, low-density and plot locations.

Figure 1. Number of respondents reporting various sources of income per household location in urban and peri-urban Marondera.

Some publications (Ambrose-Oji, Citation2009; De Neergaard et al., Citation2009; Kutiwa et al., Citation2010; Roppa, Citation2012; RUAF, Citation2012) show that urban farming households often have quite diverse livelihoods, combining various incomes and resources. For instance, Roppa (Citation2012) and the RUAF (Citation2012) argued that the poor tend to focus on staples such as cereals, vegetables, beans and root crops whereas better-off households can supplement their diets and incomes with higher value horticultural crop products, meat and dairy. Notably, Mbiba (Citation1995) found that high and middle-income households constitute the bulk proportion of urban agriculturists in Zimbabwe, Kenya and Tanzania, thus marginalising the poorest of the poor in this income activity as the formal sectors of the economy continue to collapse. Findings from the present study concur with this view and reveal that urban broiler production is not restricted to a survival strategy for the poor with no livelihood alternatives, but mostly involves the more privileged.

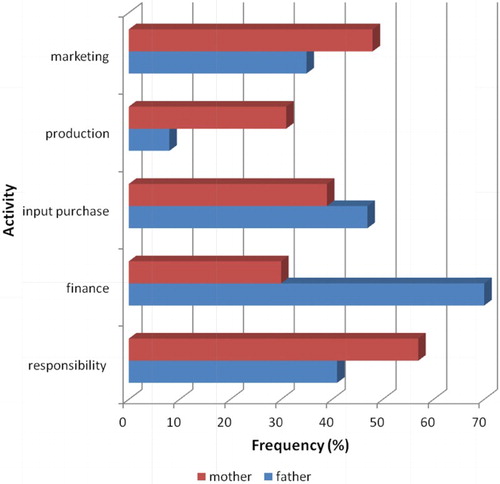

Many surveys indicate that women predominate in urban agriculture (Kutiwa et al., Citation2010) because, compared with men, they are marginal in the formal employment sector of the urban economy and occupy a central role in household food delivery (Mbiba, Citation1995; Obuobie et al., Citation2004). Men tend to dominate when the urban agriculture activities are focused on commercialised production (Drescher et al., Citation1999). However, this study revealed a predominance of women in responsibility, production and marketing activities whereas men dominate initial financing and inputs purchase (). There are two probable reasons for this situation. Firstly, urban broiler units are situated at home and thus the activities are more easily fitted into women's daily chores of household sustenance and well-being (Obuobie et al., Citation2003; Kutiwa et al., Citation2010). Secondly, men participate in broiler production only as a marginal side-line activity because they are mostly employed elsewhere (Bryld, Citation2003).

3.2 Flock sizes and stocking densities

All respondents use three commercially available strains of improved hybrid broiler chickens (Cobb500, Ross 308 and Hubbard Broiler) sourced from local (78%) or Harare-based (22%) day-old chick distributor outlets. Choice of strain is based on availability and reliability of supply. Most of the producers (80%) do not keep any other poultry species on the same property.

As shown in a typical broiler production unit in the study area housed an average of 398 broiler chickens in a range of 25–3500 birds per cycle and marketed an average of 2772 birds per year (range 150–16 000). The median number of birds kept per cycle and per year was 150 and 1000 birds, respectively. However, 79% of the respondents kept at most 200 birds per cycle, and only 8% kept more than 2000 birds. A great portion of 75% of the farmers kept at most 2000 birds per year. There was a significant difference in flock sizes across the surveyed locations (p < 0.05). Producers in high-density suburbs kept fewer birds than those in low-density suburbs and the plots. This variation could have been due to differences in land sizes available to the producers in the different areas. Generally, more land is available in the lower density locations, thus permitting larger sizes of chicken runs, and hence more birds could be kept. Secondly, larger flock sizes in lower density and plot areas are possible because of lower risk to human health and the environment (noise, odours and manure) as well as fewer neighbour complaints to the municipal authorities. A third probable reason is that residents of low-density suburbs and plots have higher incomes and more livelihood options and can therefore access reliable market outlets for their birds.

Table 2. Characteristics of urban broiler production units in urban and peri-urban Marondera (n = 55).

Findings from this study show higher flock sizes compared with the few similar studies available. For instance, commercial broiler flock sizes ranged from 25 to 1800, with a mean of 159 birds, in the peri-urban areas of Harare and Bulawayo (Kutiwa et al., Citation2010). LMAC (Citation2013) found that 85% of small-scale producers (the majority of whom reside in urban areas) keep 200 birds or less. Earlier, Kelly et al. (Citation1994) found the mean chicken flock size in Chitungwiza to be 53 birds (range 1–650), and most of the birds were kept for meat: for domestic consumption or for local sale to generate income. In recent years, due to economic pressure, urban residents have increased the number of chickens that they keep, in clear defiance of the municipal by-laws governing the number of birds kept. In this study it was observed that there are fewer urban and peri-urban residents involved in poultry agriculture, although they keep larger flock sizes than the 25 legally allowed by Marondera municipal by-laws. According to the by-laws, Marondera municipality should strictly monitor the number of birds kept and the type and design of the fowl runs. However, policing and enforcement of this by-law has somewhat been relaxed in recent years.

Broiler stocking densities used depend on climate and type of housing with regard to welfare, performance and profit considerations. Stocking density directly influences production performance, bird health and welfare, and the economic efficiency of broiler production, and the general recommendation of most authors is 10–12 birds/m2 or 30 kg/m2 maximum (Škrbić et al., Citation2009). High stocking densities give the highest economic return per unit floor space but may have negative effects on general welfare, resulting in reduced economic return per bird (Scanes et al., Citation2004). On the other hand, too light stocking densities are not economic for space utilisation and lead to excessive movement of the birds, leading to reduced growth (Mpofu, Citation2004). In the study area, stocking density was slightly lower than recommended, ranging from 6 to 14 birds/m2 with a mean of 9.5 birds/m2, and the standard deviation was low (). The Kruskal–Wallis test was not significant (p > 0.05) for stocking density across household location in Marondera (). A lower stocking density is advantageous in the study area since farmers use a naturally ventilated, semi-permanent type of housing and therefore the environment cannot be controlled.

Table 3. Mean and standard error (SE) for characteristics of broiler production units across household location in urban Marondera.

Table 4. Mean ranks for broiler unit characteristics across household location according to the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Similar to stocking density, mortality rates did not vary significantly across household location in the study area (). Mortality rates were higher in the high to medium-density suburbs compared with lower density locations, although the difference was not significant (p > 0.05). The reported mortality rate had an average of 7.4% and ranged from 1.6 to 37%. The mortality rate was therefore higher than the recommended targets of less than 3% and thus contributed to reduced profitability of broiler production in urban and peri-urban Marondera. This concurs with the observation by Faranisi & Mupangwa (Citation2011) that mortality rates were high in the small-scale broiler production sector. Farmers may have to pay more attention to bio-security, sanitation, prophylaxis and vaccination of their flocks to prevent disease and reduce on the associated losses.

3.3 Broiler marketing

Broilers were sold at age 5–8 weeks at a live weight of 1.8–2.5 kg/bird (). A Kruskal–Wallis test revealed that age at marketing was significantly different (p < 0.05) across household locations but market weight was not. Respondents with reliable marketing arrangements (contract) strictly sell off their birds earlier than those who depend on the spot market. With the spot market option, birds are grown to a larger size in order to build goodwill and therefore secure sustainable market competitiveness. The challenge is that the bird continues to eat feed before it is finally sold, impacting negatively on profits. Generally, prices are set per bird irrespective of the live weight, except where the contractual market route is used.

Table 5. Marketing aspects of broiler chickens in urban Marondera.

Most of the broilers were sold as live birds or dressed chickens, and only a few were sold as cut-up chicken portions (). Most of the producers had unstable marketing arrangements, practising direct and open marketing of the birds to local household consumers. Organised marketing is non-existent, and this militates against enhanced revenue generation. This is particularly critical for broilers since farmers incur major losses as they continue to feed broilers until a market becomes available.

Ironically, only 33% of respondents had some form of market contract with local food outlets. Most respondents indicated a preference for the open market since the birds fetch more money compared with birds produced on contract. Only a handful of farmers produced their broilers for their own food outlets and a few others had a production contract with a broiler breeder.

3.4 Broiler management practices

Broilers in the study area are kept on deep litter (cut grass or sawdust) under varied housing scenarios. Brooding was done in rooms inside human dwellings in order to protect the young chicks from cold, theft and predation by rodents. Older birds were grown out in semi-permanent fowl runs (63%), mobile wire cages (25%) or rooms in human dwellings and garages (12%). A quarter of all respondent producers used purpose-built single-deck and double-deck mobile wire/steel cages in order to maximise the use of limited land area available on their properties and therefore achieve economies of size. Use of steel wire cages may compromise welfare of the birds; although respondents did not report any adverse effects, in this regard, the producers may have had to weigh the economic benefits of keeping larger flocks at the expense of welfare versus very small flocks of birds under a good welfare system. Bedding grass was cut from roadsides at no cost and sawdust is available at a very low cost from local saw mills. Respondent producers reported a preference for grass rather than sawdust due to the risk of the young chicks eating the sawdust and dying of impaction, raising mortality levels.

Respondents used compounded feed (61%) or bought in concentrates mixed with maize on the production site. Most (65%) of the respondents used the two-phase system in their feeding programme, and the rest used the three-phase system. The majority of the farmers in the plots used the three-phase system. It is reported that the more phases used, the more efficient the feeding system in terms of growth and economics (Roppa, Citation2012). This is because multiple stages in the feeding programme allow for matching amino acid and energy supply to requirements at a specific age. Choice of feed to used was influenced by brand reputation (63% of the farmers), past experiences with the feed (63%), cost price (39%), nutrient density (24%) and market availability (10%). Results show that producers put more emphasis on brand loyalty, feed quality (causing few health problems and low mortality) and performance (weight gains) than cost price in their feed procurement decisions. This is in line with global trends where the focus has been on maximising production and profit through faster growing birds with improved feed conversion efficiency and marketing at an early age (Scanes et al., Citation2004).

Disease masks the superiority of proven broiler strains and good management results in healthy chickens that give profitable margins (Mirira, Citation2011). Only 43% of respondents vaccinated their flocks against infectious bursal disease (18%), Newcastle disease (10%) or both (16%). The majority (53%) of the producers did not give any prophylactic treatments for disease, save for coccidiostats already in the feed. Antibiotics and ethno-veterinary extracts were used for prophylaxis and therapeutic treatment by some producers (). Ethno-veterinary treatments involved mostly fresh Aloe vera (gavakava, Shona) plant material administered in birds’ drinking water to reduce stress and promote survival and growth generally, in the first week of life. Conventional antibiotics are more expensive compared with ethno-veterinary drugs.

Table 6. Percentage of broiler farmers using prophylactic and therapeutic treatments against disease in urban Marondera.

Beside vaccination and prophylaxis, chicken production units should have bio-security measures instituted in order to exclude pathogens from the site (Scanes et al., Citation2004). Sampled households in the study area achieve bio-security through use of the sanitary vacant period system (thorough cleaning and disinfection followed by resting of the poultry houses; 93%), use of the ‘all-in, all-out’ single age site system (47%) and restricted entry (43%). Least attention was given to footbaths, with only 12% having footbaths at the entrance to the chicken houses. Interestingly, the level of biosecurity found in the urban broiler units surveyed was quite high. However, these measures were still not adequate since disease outbreaks were reported by 65% of the producers.

3.5 Key challenges in the sector

Respondents were asked about their vision for the future. Almost all producers wished to expand their production and over half of them wished to change market arrangements. Institutional (private or government) technical, extension and business support services were almost non-existent in Marondera. Only the Department of Veterinary Services was consulted by some farmers for disease diagnosis. This confirmed the findings of other workers that the small-scale broiler sector is characterised by a lack of training, business mentoring and other support services (Babubi et al., Citation2004; Faranisi & Mupangwa, Citation2011). Lack of institutional support may be due to the legal uncertainty surrounding urban poultry and livestock production.

The most commonly reported challenges were related to lack of technical support, market availability and access, lack of capital and financing, prohibitive council by-laws on urban poultry flock sizes and number of residents keeping poultry, power cuts, unreliable supply and substandard chicks, space limitations and high mortality due to disease (). Other minor problems were the high cost of production, theft and production, lack of land ownership, water shortages, feed shortages and neighbour complaints of odours.

4. Conclusions

Findings in the urban and peri-urban Marondera area of Zimbabwe showed that urban poultry producers have quite diverse livelihoods, combining various resources and income sources including proceeds from chickens. Broiler production in the study area was not restricted to a survival strategy for the urban poor with no livelihood alternatives, but mostly involved the more privileged who could finance business start-up and expansion. Production units were small to medium-size, informal, fragmented backyard businesses founded on a gender-based division of labour and dominated by women. Broiler units were characterised by diversity in flock sizes, management practices, technical performance parameters and marketing aspects. Production is constrained by a lack of sectoral (technical and business) support services, shortage of capital, prohibitive urban council by-laws, lack of access to markets and disease outbreaks. From this study, the importance and potential of poultry production as a key livelihood option in urban and peri-urban areas cannot be over-emphasised. Therefore any shocks and stresses impacting on urban poultry activities can have serious consequences on livelihoods. Targeting interventions in poultry development in this country should take into account the urban production subsector. However, findings reported in this study are specific to one urban area in Zimbabwe and results may differ elsewhere.

5. Recommendations

This baseline study has revealed that there is a need for further and in-depth study of the urban chicken production sector in terms of the following aspects:

To determine the importance and contribution of the sector to urban protein supply and dietary diversity, employment creation, household income and financial liquidity, and local economic development through related upstream and downstream industries.

The potential negative impact of broilers on the environment (pollution through noise, odours and manure) and human health (risk of zoonoses), and how producers (can) capture and control these externalities (e.g. pollution abatement) in urban populated environments.

The economics of producing broilers under urban and peri-urban settings (locations, economic flock sizes, housing structures, feeding, genetics, marketing and market development, etc.).

Animal welfare issues in urban and peri-urban poultry production systems.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Eddington Gororo http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2125-8919

References

- Ambrose-Oji, B, 2009. Urban food systems and African indigenous vegetables: Defining the spaces and places for African indigenous vegetables in urban and peri-urban agriculture. In Shackleton, CM, Pasquini, MW & Drescher, AW (Eds.), African indigenous vegetables in urban agriculture (pp. 1–33). Earthscan, London.

- Babubi, SS, Ravindran, V & Reid, J, 2004. A survey of small-scale broiler production systems in botswana. Tropical Animal Health and Production 36(8), 823–34. doi: 10.1023/B:TROP.0000045951.35345.17

- Bryld, E, 2003. Potential, problems and policy implications for urban agriculture in developing countries. Agriculture and Human Values 20, 79–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1022464607153

- De Neergaard, A, Drescher, AW & Kuome, C, 2009. Urban and peri-urban agriculture in African cities. Earthscan, London.

- Drescher, A, Koc, M, MacRae, R, Mougeot, L & Welsh, J, 1999. Urban agriculture in the seasonal tropics: The case of Lusaka, Zambia. In Koc, M (Ed.), For hunger-proof cities: Sustainable urban food systems (pp. 67–76). IDRC, Ottawa.

- Faranisi, AT, 2010. Poultry breeding in Zimbabwe. http://www.ilri.org/infoserv/webpub/fulldocs/angenrescd/docs/proceedAnimalBreedAndGenetics/Poultry Accessed 4 February 2011.

- Faranisi, AT & Mupangwa, JF, 2011. Overview of the Zimbabwe poultry industry: A seminar presentation delivered on 4 May 2011. Department of Animal Science, University of Zimbabwe, Harare (unpublished).

- Kelly, PJ, Chitauro, D, Rohde, C, Rukwava, J, Majok, A, Davelaar, F & Mason, PR, 1994. Diseases and management of backyard chicken flocks in Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe. Avian Diseases 38, 626–9. doi: 10.2307/1592089

- Kutiwa, S, Boon, E & Devuyst, D, 2010. Urban agriculture in low Income households of harare: An adaptive response to economic crisis. Journal of Human Ecology 32(2), 85–96.

- LMAC (Livestock and Meat Advisory Council), 2013. A survey of smallholder poultry producers in Zimbabwe: A research paper presented at the SADC Liaison Forum, Cresta Lodge, Harare (unpublished).

- Mbiba, B, 1995. Urban agriculture in Zimbabwe: Implications for urban management and poverty. Averbury, Aldershot.

- Mirira, T, 2011. Poultry flock health: A seminar delivered in the department of animal science. University of Zimbabwe, Harare (unpublished).

- Mpofu, I, 2004. Applied animal feed science and technology. Upfront Publishing, Leicestershire.

- Obuobie, E, Danso, G & Drechsel, P, 2003. Access to land and water for urban vegetable farming in Accra. Urban Agriculture Magazine 11, 15–7.

- Obuobie, E, Streiffeller, F & Kesseler, A, 2004. Women in urban agriculture in West Africa. Urban Agriculture Magazine 12, 13–5.

- Penz, AM Jr & Bruno, DG, (Provimi America Latina, Campinas, Brazil), 2011. Challenges facing the global poultry industry until 2020. Proceedings of Australian Poultry Science Symposium 22, 49–55.

- Roppa, L, 2012. Heading for the future: The food facts. AllAboutFeed 20(1), 8–11.

- RUAF (Resource Centre on Urban Agriculture and Food Security), 2012. Urban agriculture. http://www.ruaf.org/node Accessed 20 January 2012.

- Rushton, J, 2009. Economics of animal health and production. CAB International, Wallingford.

- Scanes, CG, Brant, G & Ensminger, ME, 2004. Poultry science. 4th edn. Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Škrbić, Z, Pavlovski, Z & Lukić, M, 2009. Stocking density: Factor of production performance, quality and broiler welfare. Biotechnology in Animal Husbandry 25(5–6), 359–72. doi: 10.2298/BAH0906359S

- SPSS Inc., 2007. Statistical package for social scientists version 16.0 (SPSS 16.0) for Windows.

- ZPA (Zimbabwe Poultry Association), 2011. Poultry production in Zimbabwe. Feedmatters, Edition 1, 8–11.

- ZIMSTAT (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency), 2013. Zimbabwe national population census 2012 – National Report. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Harare. http://www.zimstat.co.zw/dmdocuments/Census/CensusResults2012/National_Report.pdf Accessed 16 August 2014.