ABSTRACT

Studies of informal urban transport modes have been carried out in several countries in Africa and Asia. Hardly any have been conducted in Zimbabwe. This study set out to establish the prevalence of an informal urban transport system and the rationale for its existence. The research was carried out in Masvingo and Harare. The study used qualitative approaches such as participation–observation, conversations with stakeholders and open-ended questionnaires. The data were summarised into tables and graphs. Among the findings were that an informal urban transport system is very active in both cities and that the existence of the system is justified due to the inadequate services provided for certain types of commuter. It is recommended that the vital role played by informal taxis should be recognised and managed. Specific routes could be mapped out for them, with a flexible licensing regime to match.

1. Introduction

Because of the challenging economic situation in Zimbabwe, many citizens are turning to self-provisioning of employment in the informal sector, including operation of unregistered taxis. Scores of unlicensed taxis with smashed-up windshields are seen driving around the streets of Harare; often these taxis are observed to be driving hurriedly away from law enforcement agents trying to stop them. The taxis are unlabelled but one can easily identify them as they usually park in particular locations around the city and touts in attendance will be calling for ‘one more passenger’ before the taxi can depart. Another easy way of identifying the taxis is that over 50% of them have their windshields badly cracked, usually on the driver's side. The phenomenon was observed particularly in Harare. An interesting aspect is that in Masvingo most of the taxis do not have smashed windshields and a few law enforcement officers have even been observed to use the taxis to travel to certain parts of the city.

2. Literature review

Because of the rapid increase in urban populations of cities in developing countries and low-level development of public transport infrastructure, members of the public find themselves resorting to informal urban transport systems. Guillen et al. (Citation2013) refer to unique kinds of public transportation used by people in the low-income brackets (the average Filipino uses door-to-door transport services). Kamuhanda & Schmidt (Citation2009) point out that the public transport system in Kampala consists of buses, matatus, motorcycle taxis and car taxis. Matatus, freed from any form of licensing by Jomo Kenyatta in 1973, are minibuses that Kenyans in the low-income bracket rely on for daily transportation (Mutongi, Citation2006). A study by Herro (Citation2006) focuses on how bicycle taxis have rapidly surpassed the minibus taxis as the main mode of public transport in Kisumu (western Kenya). Bicycle taxis and handcarts are the subject of a paper on informal public transport from Malawi (Jimu, Citation2008). In a study drawing on case studies taken from Harare (Zimbabwe), Accra (Ghana) and Colombo (Sri Lanka), Fouracre et al. (Citation2006) argue for a more participatory approach to transport planning and policy-making so as to come up with strategies that support the needs of low-income groups and achieve broader poverty alleviation goals. One study gives an idea of the size of the illegal taxi industry. A significant number of minibus taxis used as public transport vehicles in South Africa operate illegally, up to 80% in Johannesburg and up to 50% in Cape Town (Lomme, Citation2009). In Zimbabwe's cities, licensed public transport consists mainly of minibuses (commuter omnibuses) and taxis for hire. The minibuses ply pre-determined routes between the various suburbs and the Central Business District. However, many areas of the city are served by unlicensed taxis.

A number of studies have been conducted on the integration of informal urban transport systems with formal systems and on the regularisation or replacement of the informal systems. A study on the operations of rapid transit systems in the United Kingdom and in the USA (Leash, Citation2013) concluded that increased access to existing rapid transit systems will increasingly be dependent on implementing existing technologies and developing new ones. The re-emergence of the jitney and new taxi services are cited as examples. Leash (Citation2013) describes a jitney as a shared taxi, which usually takes passengers on a fixed or semi-fixed route without timetables. Jitneys may stop anywhere to pick up or drop off passengers. A study by Del Mistro & Behrens (Citation2015) uses a public cost model to assess the impacts of including paratransit operators in public transport reform projects as feeder services to a trunk-distribution service. They conclude that if the proposed reform is adopted, it should include strategies that would absorb as many paratransit operators as possible; an increased number of commuters on the improved trunk service would also create opportunities for providing increased feeder services.

A study by Mfinanga (Citation2012) reports on the challenges of introducing a bus rapid transit system in the city of Dar es Salaam, to replace about 5000 commuter minibuses or daladalas. One of the main problems is to figure out how best the pre-existing operators can be integrated into the new system. Venter (Citation2013) reports on the relative success of the integration of a ‘fragmented and informal public transport industry’ into the bus rapid transit system implemented in the city of Johannesburg between 2009 and 2011. Ommeh et al. (Citation2015) examined an unsuccessful attempt at phasing out the 14-seater matatus in Kenya in favour of larger capacity buses. The paper concludes that stakeholder participation in the decision-making process would bring about a deep understanding of policy effects. Paget-Seekins et al. (Citation2015) reviewed a process of consolidation of informal urban transport providers in Bogotá, Santiago and Mexico City into fewer, larger regulated companies with a larger role for the authorities. They established that formalisation increased costs involving public subsidy and higher fares, thereby putting financial pressure on the public sector. They suggest that because of these problems instability in the regulatory cycle would persist, creating opportunities for informal sector service. Hidalgo & King (Citation2014) reviewed the experience of the two Colombian cities of Cali and Bogotá in integrating informal urban transport systems into a regulated city-wide transport system. While acknowledging significant progress, they concluded that a very gradual approach may experience difficulties emanating from discontinuities in political leadership and weak institutional capacity.

The issue of informal urban transport can be viewed in the context of resilient urban communities. When used in the context of ecosystems and ecological processes, the concept of ‘resilience’ means the capacity of a system to recover or re-establish itself after a large disturbance or disruption (Shade et al., Citation2012), or long-term persistence and function (Hale & Sadler, Citation2012). Socio-economically, resilience can be viewed as ‘a positive, adaptive response to adversity’ (Chaskin, Citation2008:66). Resilience can be at an individual level or at the level of a whole community.

3. Problem statement

Informal provisioning of urban passenger transport appears to be quite common in Zimbabwe's cities. This is despite the fact that urban planning authorities issue licences to legally registered operators – for a stipulated fee. The legal taxis operate from designated locations strategically sited around the city; they follow pre-determined routes stipulated in the licences. It was not clear what kind of commuters patronise the illegal taxis and why they preferred to use them. There was a need to explain the phenomenon, especially in view of the fact that these illegal taxi operators are often involved in running battles with law enforcement agents (national police and municipal police). On quite a few occasions, the illegal taxis have been involved in serious road traffic accidents, some of which have resulted in fatalities. There was a need to examine the reasons for the persistence of the illegal taxis in the face of opposition from the authorities and the potential danger to both operators and their passengers.

4. Aims and objectives of the study

This study set out to establish the prevalence of an informal taxi system in the cities of Harare and Masvingo and the reasons for the existence of such a system. The study proceeded to seek answers to the following questions:

What commuter routes do the informal taxis operate on and why?

On average, how many commuters and how many operators are involved daily on each of the five routes examined in the study?

What are the socio-economic profiles of the operators of the informal taxis and why do they operate the informal taxis?

What are the socio-cultural profiles of the commuters who travel on these routes and what is their motivation for using this form of transport?

In particular, the study set out to:

identify the characteristics of the routes patronised by informal taxis;

estimate the numbers of operators and commuters involved on each route daily;

establish the socio-economic profiles of the operators of the informal taxis and their motivation for operating the service; and

assess the socio-demographic profiles of the commuters who use the informal taxis and their motivation for doing so.

5. Research design and methodology

The research involved a qualitative approach. The study was partly a generic qualitative approach focusing on ‘(1) how people interpret their experiences, (2) how they construct their worlds, and (3) what meaning they attribute to their experiences’ (Merriam, Citation2009:23). The approach included the descriptive qualitative approach and interpretive description (Crotty, Citation1998). It was also inductive, looking at several case studies to arrive at general conclusions about informal urban taxi operations in Zimbabwe.

A questionnaire survey was used to gather data on socio-economic and socio-demographic aspects; the findings from the survey would serve to validate the findings of the qualitative interviews. Validation is important because it is believed by some critics of the qualitative approach that there is a tendency towards an anecdotal approach to the use of data in relation to conclusions or explanations (Silverman, Citation2000). The use of statistical data also helps to make the findings of the qualitative approach more reliable. Reliability is defined as ‘the degree of consistency with which instances are assigned to the same category by different observers or by the same observer on different occasions’ (Hammersley, Citation1992:67).

5.1 Data collection processes

The Masvingo part of the research was carried out mainly in March and July 2012, with two corroborative visits in June and August 2014. The Harare part of the study was carried out between August 2012 and August 2014. After an initial reconnaissance survey of the sites of operation of the illegal taxis in both cities, the routes to be studied were selected on the basis of the distinctiveness of the type of commuter served on the particular routes. Maps of the relevant parts of town were examined and distances covered by the routes were estimated as closely as possible, using Google Earth software.Footnote1 The researcher undertook participant observation, commuting along each of the routes on several occasions.

A lot of data were gathered from observation of the taxi operators in their interactions with fellow operators and with commuters. The qualitative approach generated data on the socio-demographic profiles of the participants. Conversations were held with the operators, some of the taxi owners and some of the passengers. The subjects of the discussions included socio-demographic profiles of commuters, choice of commuter routes, frequency of trips per day, commuter fare, interaction with commuters, relations with other operators (both legal and illegal), safety issues and relations with law enforcement agents. Observations were made on the characteristics of the routes taken and vehicle identification was done so as to determine the average number of vehicles involved on each route.

An open-ended questionnaire was designed, pre-tested by administration to four operators in Masvingo and five operators in Harare. After some refinement, the questionnaire was then administered on larger samples. Eight questionnaires were distributed on the Rujeko–College route and 10 questionnaires were distributed on the City–Rhodene route in Masvingo. In Harare, six questionnaires were administered on the Masotsha Ndlovu Way route, eight on the Roadport–Copa Cabana route, and 11 on the City–Avondale route. The questionnaire looked at vehicle ownership, level of education of drivers, marital status of operators, length of stay in the illegal taxi business, level of income earned by operators and attitudes to the illegal taxi business. The intention was to relate these variables to the operators’ resilience in the illegal taxi business.

5.2 Data analysis processes

Data processing included downloading digital maps of routes from the Internet and editing them to suit the context of the study. Regrettably, it was not possible to obtain a usable digital map of Masvingo Central Business District where one of the routes originated from.

The question of sample size in qualitative research is the subject of much discourse; interviews are carried out until there is data saturation. According to Marshall et al. (Citation2013:2), data saturation ‘entails bringing new participants continually into the study until the data set is complete, as indicated by data replication or redundancy’. In this study, data saturation was reached at between four and five questionnaires on all the routes. Consequently, the researcher distributed between five and 11 questionnaires on the various routes studied. The questionnaire responses were capturing data generated through qualitative interviews and synthesised into five major themes: route characteristics; commuter socio-demographic profiles; socio-demographic profiles of the illegal taxi drivers (with a number of sub-themes); level of satisfaction with the illegal taxi business; and negative aspects of the business. The data were summarised into tables and graphs.

6. Results and discussion

The route characteristics, socio-demographic profiles of commuters and illegal taxi operators, tables and graphs which summarise relevant data are presented and discussed in this section.

6.1 Masvingo routes' characteristics

In Masvingo, the starting point for the City–Rhodene route is at the junction of Hellet Street and the Masvingo–Harare road (geographical coordinates –20.070968°, 30.830082°), about 180 m west of a busy supermarket. This location is not well served by the registered commuter omnibuses which operate from a major bus terminal half a kilometre to the south-eastern part of Masvingo town. The terminal is located near a major supermarket, surrounded by several other smaller supermarkets. This terminal serves the majority of commuters residing in the high-density suburbs to the south-east, south and south-west of the city.

The City–Rhodene route (and vice versa) was 4.39 km to the northern end of Rhodene, along the Masvingo–Harare road (–20.041459°, 30.810684°). However, the route had several variations to it, depending on the combination of the commuters on a particular trip. The illegal taxis’ routes could include going to Northlea, an extension of Rhodene; taking children to school or crèche in some part of Rhodene or across the river to Eastview; passing through Masvingo General Hospital; passing through the industrial sites; or going to peri-urban locations such as Clovelly and Showground. Some families arranged for children to be picked up from school and delivered to their residences while the parents were still at work.

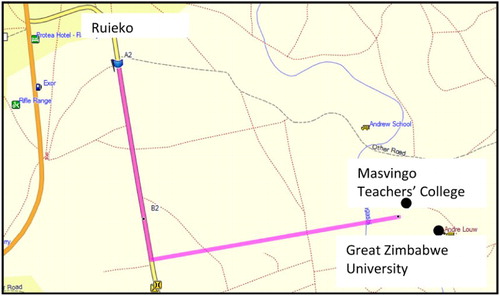

The second route selected for study in Masvingo was the Rujeko–Masvingo Teachers’ College/Great Zimbabwe University route, popularly referred to as the Rujeko–College route. This starts from Rujeko suburb (–20.092753°, 30.837763°), and turns at a junction located at –20.104521°, 30.839952° to Masvingo Teachers’ College/Great Zimbabwe University campus (–20.104360°, 30.860680°).

illustrates this Rujeko–College route, which was 3.4 km long. While the registered commuter omnibuses served the commuters on this route at peak periods in the morning and in the late afternoon, the service was non-existent for the rest of the day. Illegal taxi operators identified the need to provide passenger services during the off-peak periods.

6.2 Socio-demographic commuter profiles for Masvingo routes

The socio-demographic profiles of the commuters who used the illegal taxis were quite varied. The commuter categories on the City–Rhodene route included the following:

Male and female adults of working age who did not own cars but travelled to and from their workplaces each working day.

Unemployed/retired adults who travelled to and from town to pay their bills or to do some shopping.

Young children (accompanied by adults) travelling to and from crèche.

School children on their way to and from primary and secondary school.

These profiles hardly fit the mould of people who might be regarded as ‘aiding and abetting a criminal activity’ – that is, patronising an illegal business activity. An interesting observation that was made on four different occasions on this route was that of uniformed police officers boarding the illegal taxis. When asked about the irony of this situation, the officers responded that they had no option but to use the illegal taxis since there were no licensed taxis servicing this route.

The socio-demographic profiles of commuters on the Rujeko–College route comprised mostly students to and from Masvingo Teachers’ College and Great Zimbabwe University. Some of the students reside on campus but, from time to time, have to travel to Rujeko, and on to town to stock up on some supplies or to visit various establishments. The majority of students reside off-campus and travel to and from the institutions at various times of the day. While licensed taxis are available at peak periods (early in the morning and at the end of the working day), illegal taxis provide transport to the students during the rest of the day. Staff of the colleges who use the institutions’ buses to and from work resort to using the illegal taxis if they need to go to and from town before the end of the working day.

6.3 Harare routes' characteristics

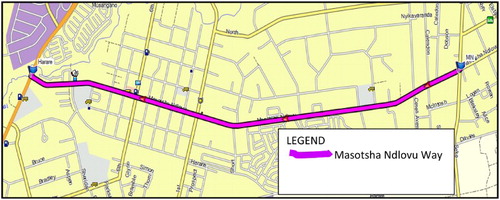

The taxi routes selected for study in Harare were: Masotsha Ndlovu Way (between Simon Mazorodze Road and Seke Road) in Waterfalls (6.6 km) (from Simon Mazorodze Road, –17.890492°, 31.0072448° to Seke Road, –17.890002°, 31.069733°); Roadport–Copa Cabana bus terminus (1.34 km) (–17.829589°, 31.056343°, turn left at –17.827301°, 31.055914° along Nelson Mandela, to the vicinity of Leopold Takawira/Chinhoyi Street, –17.830509°, 31.043211°); and City–Avondale (2.40 km), which usually extended to Avondale shops a further 850 m to the north; from Townhouse (–17.832203°, 31.045185°, along Leopold Takawira to Parirenyatwa Hospital and on to Avondale shops, –17.802950°, 31.036688°). illustrates the Masotsha Ndlovu Way route.

There are no licensed commuter omnibuses which travel directly along Masotsha Ndlovu Way. Commuters who take illegal taxis that travel along Masotsha Ndlovu Way do not want to travel all the way to town and then all the way back from town along Seke Road to Masotsha Ndlovu Way on the licensed commuter omnibuses – just to get to destinations located less than 7 km along this road. The commuters comprise travellers who have alighted from buses plying the Masvingo and Seke roads; these travellers may have no business to conduct in the city and just want to go to Waterfalls, Hatfield and the northern outskirts of Chitungwiza. Other commuters from these suburbs travel along Masotsha Ndlovu Way to these major routes out of Harare, and to the other suburbs east and west of Waterfalls.

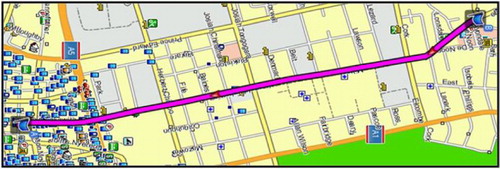

illustrates the Roadport–Copa Cabana route. This route links up two very busy bus termini. At the time of the study, no official taxis plied this route.

illustrates the City–Avondale route. This route is very busy with work-related commuting heading in both directions.

6.4 Socio-demographic profiles of commuters on Harare routes

Interviews with some of the drivers and commuters, as well as observations by the researcher during participant observation, revealed the existence of commuters with a variety of socio-demographic profiles:

Commuters on the Roadport–Copa Cabana route comprise heavily laden travellers who have just alighted from long-distance buses from Mutare and other destinations in the eastern parts of Zimbabwe. Some of the commuters will be arriving by bus from outside the country from destinations such as Malawi, Zambia or South Africa, and will be on their way to one of the western suburbs of Harare. They also include travellers on their way to Roadport to catch a long-distance bus out of Harare to destinations outside Zimbabwe.

Commuters on the City–Avondale route include a large contingent of health workers to and from Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals. Some are travellers from the city who do not have the patience to wait for a licensed commuter omnibus to fill up and then take them to Avondale on its way to destinations beyond Avondale. Commuters who live in the Avenues area of Harare also make use of a combination of modes of transport which include licensed commuter omnibuses, illegal taxis and private cars.

6.5 Composite Harare–Masvingo results

summarises the socio-economic profiles of commuters on each of the five routes in Harare and Masvingo cities. The needs of commuters on each route are unique, creating opportunities for illegal taxi operators to offer their services.

Table 1. Socio-economic profiles of commuters on each of the five routes studied

presents a summary of operational statistics such as average number of vehicles on each route, average number of trips per day, average number of passengers per trip, average number of commuters carried on each route per day, average number of passengers per trip per vehicle and average daily takings grossed by the operators. This gives a comprehensive picture of how the illegal taxi business operates both from the perspective of the individual operator and from the point of view of a group of operators on each route.

Table 2. Summary operational statistics: all routes plied by unlicensed taxis

6.6 Socio-demographic profile of illegal taxi operators

This section examines results of the study presented in various graphs. The results are the average percentages computed for all five routes studied in the cities of Harare and Masvingo.

6.6.1 Age range of operators of taxis

illustrates the age ranges of the illegal taxi operators.

The largest group of illegal taxi operators (53.6%) were in the 26–30 year range. The next group (28.6%) was in the age range 20–25 years. This was followed by the 30–35 year group (13.7%). This suggests that the peak period for operation of the illegal taxi business was the 20–30 year group (82.2%). The under-20 group (4%) is not yet fully engaged in this somewhat risky business. The over-30 group was made up of drivers who were actively considering quitting the trade or were about to reach a stage where they were ready to branch off into other activities. These are the most experienced operators who provided insights into the dynamics of the illegal taxi trade.

6.6.2 Ownership of taxis

summarises the vehicle ownership pattern in the illegal taxi ownership business.

Over half the illegal taxis on the streets (52%) are not owned by the drivers. The vehicle owners employ the drivers on a full-time basis or hire them and pay them a commission. This is because many of the drivers cannot raise enough money to purchase their own vehicles. Twenty-six per cent of the illegal taxis on the roads in Harare and Masvingo are owner-operated. The rest of the illegal taxis are owned by a member of the driver's family (17%) or a relative (8.3%). These are usually siblings or parents of the driver who may be assisting the driver to be gainfully employed. The issue of ownership is important in determining the type of contract entered into between the driver and the owner. It is also important in determining the financial arrangements for servicing and maintaining the vehicle in a sound mechanical condition.

6.6.3 Level of education of drivers of illegal taxis

shows the levels of education of the illegal taxi drivers.

The majority of drivers (71.2%) were holders of a high school certificate. The next group of drivers (21.8%) held a school-leaving certificate (Ordinary Level). Several drivers said they had not been able to proceed with their studies beyond high school for various reasons. Some (3.2%) indicated that they had attained a primary school level of education. A very low percentage (1.8%) indicated that they were holders of a tertiary-level qualification; they had not been able to secure employment that appropriately reflected their level of education. Some had previously worked for some organisations but had lost their jobs. Conversations with several of the drivers led the researcher to conclude that the better educated drivers regarded their operation of an illegal taxi as a temporary situation to be endured until something better came along.

6.6.4 Marital status of drivers

shows the marital status of the illegal taxi drivers.

The majority of the illegal taxi drivers (74.6%) were married with children. This is significant in that these drivers, being family men who are the main breadwinners, would be motivated to hold down a steady job. They would ensure that they had an alternative income before they quit the illegal taxi operation. The category of married men without children was 9.4%. The single category was 12.6%. Those in the divorced category were 3% of the total. Most of the drivers the researcher conversed with stated that in the current economic situation prevailing in Zimbabwe, most drivers would hold on to their illegal taxi operations. Regardless of their marital status, the drivers said they were responsible for the up-keep of other dependents in their extended families.

6.6.5 Length of stay in the illegal taxi business

shows a summary of the lengths of stay of the operators in the illegal taxi business.

The largest group of illegal taxi drivers (41.6%) had been in the business for 1.5–2 years. Twenty-one per cent of the drivers had been in the business for 6–18 months; 20.7% had been in the business for 2–3 years. Some 9.5% had been in the business for less than six months while a fairly small group (7.1%) had been in the business for more than three years. The operators explained that most people used the illegal taxi business as a stepping stone to operating a properly licensed commuter omnibus or taxi business; others start another business which is not in the transportation field. They pass on the illegal taxi business to a family member or sell the vehicle to other interested parties. In short, while particular drivers or owners may move out, the illegal taxi business continues under a new operator. This shows that while individual operators may opt out of the operation, the business model will persist.

6.6.6 Operator's level of satisfaction with income from illegal taxi business

shows the illegal tax operators' level of satisfaction with the income they earned from the business.

The range of daily takings from the illegal taxi operations ranged from $40.00 to $105.00 (see ). Depending on whether he was the owner of the vehicle or just the operator of the business, the driver received only a fraction of this amount. There were also variations on the level of commission/wages earned by each driver dependent on what their contracts of employment stated. The majority of drivers (61.1%) regarded the level of incomes they earned as satisfactory for the time and effort they put in. Around 18% thought the income they earned ranged from good to very good. Slightly above a fifth (21.6%) of the operators thought the income was less than satisfactory. Most of the drivers said the earnings from the job enabled them to give their families a reasonably good standard of living.

6.7 Positive aspects of the illegal taxi business

Informal taxi drivers identified four positive aspects of the illegal taxi operation. summarises these aspects.

These positive aspects included the provision of steady employment (69.4%), flexible routes (10.3%), breaks between trips (9.1%) and comparative ease with which to manage the business (11%). The majority of the drivers appreciated the fact that the informal taxi business provided them with a steady job, enabling them to support themselves and their families. A sizeable number of drivers said that dealing with a smaller number of passengers was easier to manage than in the licensed taxi business. While a relatively short waiting period between trips and operating on flexible routes were not rated as highly, drivers still felt that these were positive aspects of the operation.

6.8 Negative aspects of the illegal taxi business

shows the aspects of the illegal taxi business regarded as negative by the drivers.

The most negative aspect of the illegal taxi business was the highly competitive nature of the business. This was cited by 43.2% of the drivers. Since the business is not regulated, it is not unusual for new operators to suddenly appear on the scene and add to the number of taxis on specific routes. The effect of such a development is to reduce the number of passengers available to individual operators; consequently, the number of trips to be undertaken by each operator may be reduced, leading to a drop in daily takings. This often causes tension among the operators but since they are all operating illegally they can hardly prevent the involvement of any new players. Such tensions are dealt with following an agreed procedure. The trips are usually scheduled on a first come, first served basis, and by agreement no driver is allowed to jump the queue – everyone must await their turn.

Frequent run-ins with law enforcement agents were the next major challenge. This was cited by 38.2% of the drivers. As the informal taxis operated without a licence, they were often stopped and fined by either the national police or the municipal police. Sometimes the taxis’ wheels are clamped if the vehicle is parked in a prohibited area. The errant taxis are towed away to a city-controlled parking area; the operators have to pay a fine to retrieve their vehicles. To avoid getting caught up in this, the drivers often drive off at high speed at the approach of the law enforcement agents. This sometimes leads to road traffic accidents. The police, frustrated at their inability to force the illegal taxis to stop, sometimes smash the wind shields of the taxis on the drivers’ side as the vehicles pass them.

The other negative aspects of the illegal taxi business mentioned by the drivers were the high accident risk and the crowding of the passengers in the small vehicles. The perception of a high accident risk (11.4% of respondents) is related to the run-ins with the law enforcement agents. Even though the drivers know that they have to follow the road rules required of every driver, they often take risks to avoid having their vehicles impounded. A number of the drivers (8.2%) said they were somewhat embarrassed at having to squeeze four or five passengers into their small-to-medium-sized vehicles. However, they said they had to do this in order to achieve their targets of daily takings. They said they did not operate bigger vehicles as it was more economic on fuel consumption to operate cars whose engine size was below 1500 cc.

6.9 Contribution to resilience of the urban community

The operation of the illegal taxis offers a source of income for the taxi owners. For the hired driver, it provides steady employment and an income, enabling the drivers to provide for their families. For the local community, the taxi service provides a reliable (albeit informal) transport service where otherwise there is none. In some ways the informal taxis provide a more convenient service than the registered commuter omnibuses. Their routes are flexible and adaptable depending on the actions of the law enforcement agents and the clients’ needs.

On the City–Rhodene route in Masvingo, the taxis provide a door-to-door service for the convenience of the commuters. This is especially convenient for the heavily-laden commuter who is returning from a shopping trip, an elderly client who has difficulty walking a long distance to a busy and noisy bus stop, or young unaccompanied children returning from school. On the morning journey, the taxi will take a flexible route to deliver school children at the school gate, health-care workers at the main hospital and industrial workers in the industrial sites while on its way to town.

Among the strengths of the informal urban taxi business are the operators’ ability to adapt to changing circumstances and to use neighbourhood characteristics to contribute to the local community's resilience and sustainability. In the face of onslaughts from law enforcement agents, increased cost of fuel and operational changes to the licensed commuter omnibuses, the informal taxis have managed to find ways to remain in business.

7. Conclusions

Commuter routes patronised by the illegal taxis are generally short (less than 6 km) and are not well served by licensed operators.

On average, 8310 commuters on the three Harare routes and 4950 commuters on the two Masvingo routes are ferried daily.

The operators of the illegal taxis are otherwise unemployed, unskilled low-level workers.

The commuters who travel on the illegal taxis are people whose unique needs are not served by the registered taxis.

8. Recommendations

Taxi licensing authorities should design routes that cater for all categories of commuter – not just those heading to the Central Business District and back.

City councils should base their licensing of routes on empirical evidence of commuter movement patterns.

Illegal taxis create employment for unemployed people while providing a public transport service; they should be licensed to operate on special routes they participate in identifying.

Commuters with unique transit needs (not just mainstream commuters) should be catered for in public transport planning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1Available from http://www.google.com/earth/download/ge/.

References

- Chaskin, RJ, 2008. Resilience, community, and resilient communities: Conditioning contexts and collective action. Child Care in Practice 14(1), 65–74. doi: 10.1080/13575270701733724

- Crotty, M, 1998. The foundations of social research. Sage, Los Angeles, CA.

- Del Mistro, R & Behrens, R, 2015. Integrating the informal with the formal: An estimation of the impacts of a shift from paratransit line-haul to feeder service provision in Cape Town. Case Studies on Transport Policy 3(2), 271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cstp.2014.10.001

- Fouracre, PR, Sohail, M & Cavill, S, 2006. A participatory approach to urban transport planning in developing countries. Transportation Planning & Technology 29(4), 313–30. doi: 10.1080/03081060600905665

- Guillen, MD, Ishida, H & Okamoto, N, 2013. Is the use of informal public transport modes in developing countries habitual? An empirical study in Davao City, Phillipines. Transport Policy 26(1), 31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.03.008

- Hale, JD & Sadler, J, 2012. Resilient ecological solutions for urban regeneration. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Engineering Sustainability 165(1), 59–68. doi: 10.1680/ensu.2012.165.1.59

- Hammersley, M, 1992. What's wrong with ethnography? Methodological explorations. Routledge, London.

- Herro, A, 2006. Bicycles leave Kenyan taxis in the dust. World Watch 19(4), 6.

- Hidalgo, D & King, R, 2014. Public transport integration in Bogotá and Cali, Colombia: Facing transition from semi-deregulated services to full regulation citywide. Research in Transportation Economics 48, 166–75. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2014.09.039

- Jimu, IM, 2008. Urban appropriation and transformation: Bicycle taxi and handcart operators in Mzuzu, Malawi. Langaa RPCIG, Mankon.

- Kamuhanda, R & Schmidt, O, 2009. Matatu: A case study of the core segment of the public transport market of Kampala, Uganda. Transport Reviews 29(1), 129–42. doi: 10.1080/01441640802207553

- Leash, MC, 2013. Innovative concepts in first-last mile connections to public transportation. In Jones, SL (Ed.), Urban Public Transportation Systems: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Urban Public Transportation Systems. ASCE, 2013, Reston, VA, USA. ProQuest ebrary. Accessed 10 August 2015.

- Lomme, R, 2009. Should South African minibus taxis be scrapped? Formalizing informal urban transport in a developing country. http://www.codatu.org Accessed 10 August 2015.

- Marshall, B, Cardon, P, Poddar, A & Fontenot, R, 2013. Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. Journal of Computer Information Systems 2013(1), 11–22. http://iacis.org/jcis/articles/JCIS54–2.pdf Accessed 10 August 2015.

- Merriam, SB, 2009. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

- Mfinanga, DA, 2012. Challenges and opportunities for the integration of commuter minibus operators into the Dar es Salaam City BRT System. http://trid.trb.org/view.aspx?id=1250430 Accessed 10 August 2015.

- Mutongi, K, 2006. Thugs or entrepreneurs? Perceptions of matatu operators in Nairobi, 1970 to the present. Africa 76(4), 549–68. doi: 10.3366/afr.2006.0072

- Ommeh, M, Chitere, P, Mitullah, WV, McCormick, D & Orero, R, 2015. The politics behind the phasing out of the 14-seater matatu in Kenya. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/85489 Accessed 10 August 2015.

- Paget-Seekins, L, Dewey, OF & Muñoz, JC, 2015. Examining regulatory reform for bus operations in Latin America. Urban Geography 36(3), 424–38. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2014.995924

- Shade, A, Read, JS, Youngblut, ND, Fierer, N, Knight, R, Kratz, TK, Lottig, NR, Roden, EE, Stanley, EH, Stombaugh, J, Whitaker, RJ, Wu, CH & McMahon, KD, 2012. Lake microbial communities are resilient after a whole-ecosystem disturbance. Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology 6(12), 2153–67.

- Silverman, D, 2000. Doing qualitative research: A practical approach. Sage Publications, London.

- Venter, C, 2013. The lurch towards formalisation: Lessons from the implementation of BRT in Johannesburg, South Africa. Research in Transportation Economics 39(1), 114–20. http://www.google.com/earth/download/ge/ Accessed 20 August 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2012.06.003