ABSTRACT

Scholars of economic development have always hinted that the urbanisation process in the developing world does not follow the historical patterns discerned in the developed world where a strong relationship between a country's gross domestic product and urbanisation had been observed. To confirm or refute this thesis, this study considers the pattern of relationships between the national economic growth rate and urbanisation rates in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries. Comparison is made between SSA countries and emerging and developed economies. Results indicate that whereas the traditional thesis still holds for SSA countries (i.e. they urbanise without economic growth), new antithetical trends are also discernible where urbanisation takes place with economic growth, thereby revealing a whole new dimension of urbanisation and economic growth relational patterns in Africa.

1. Introduction

Urbanisation, widely understood in development literature as the proportion of the national population living in urban areas (see for instance Davis & Golden, Citation1954; Preston, Citation1979; Henderson, Citation2002; Bertinelli & Strobl, Citation2003), is historically linked to economic growth phenomenon in developed economies (Henderson et al,. Citation2013). Economic growth, in this context, was defined by Kuznets (Citation1973) as the long-term rise in a country's capacity to supply diverse and increasing volume of goods and services to its population owing to advancing technology and changing institutional structures.

In the developed world, economic growth entailed the transformation of each country from a rural agricultural economy to an industrial service-based economy, with the advancing technology leading to introduction of labour-saving technologies that release labour from agriculture to non-agricultural activities (Henderson, Citation2003). This transformation therefore involved urbanisation because workers moved from farms to firms to engage in non-agricultural production and the firms clustered in cities to take advantage of Marshallian externalities (after Marshall, Citation1890). This may not have been the case for the developing world.

Therefore, as early as the 1950s, scholars started focusing on urbanisation and interrelated economic growth in developing countries with the hint that it could be taking a different path. For instance, Hoselitz (Citation1953) looked at the role of cities in economic growth of developing countries while Davis & Golden (Citation1954) directly explored the link between urbanisation and economic growth in developing countries. Similarly, Hoselitz (Citation1957) studied the link between urbanisation and economic growth with specific reference to Asia. Since then there has been growing focus on urbanisation in developing economies. Despite this research interest, glaring gaps have been identified. Becker & Morrison (Citation1999:1675), for instance, observed that ‘[g]iven the vast literature on migration and urbanisation in developing countries, it is perhaps surprising that so little is known about actual patterns’. Duranton (Citation2014:3) noted that the major challenge to developing economies ‘is to ensure that their urban systems act as drivers of economic growth’ instead of acting as its brake. Such studies have continued to date, nonetheless few studies have been undertaken for Africa, especially sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

SSA is an intriguing region in terms of economic development. As noted by Cohen (Citation2006) the region faces a greater set of development challenges than any other region in the world. Bloom & Sachs (Citation1998:207), on the other hand, noted that poverty in the region ‘is one of the most obdurate features of the world economy’ and that since the industrial revolution era SSA has remained the poorest and the slowest growing region in the world. This study therefore focuses on SSA's urbanisation and economic growth relational patterns to bring up their implications for development in the region. To discern the relational pattern, for each SSA country, the study charted its gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates against urbanisation growth rates within the period 1982–2012. Thereafter two main typologies of relational patterns were observed: countries where real GDP growth rate is closely related to urbanisation; and countries where the two variables are not related.

2. Theoretical models of relational patterns

2.1. Developed economies' relational pattern

Theoretically, urbanisation and economic growth should go together (Annez & Buckley, Citation2009): in the history of economic development, there is no country that has ever reached middle-income status without a significant population shift into cities. This perspective is grounded in the modernisation theory of urban development. In this context, the ‘economic power’ of urbanisation is derived from two primary channels – the division of labour and economies of scale (McGranahan et al., Citation2009).

The discussion on ‘division of labour’ originates from the pioneering thoughts by Adam Smith, who explained the benefits for productivity that arise from specialisation between producers. The division of labour is believed to have accounted for the great leap forward from craft production to factory production that gave rise to the industrial revolution. According to Quigley:

The gains from specialisation arise because denser aggregations of urban communities (conurbations) with a larger number of firms producing in proximity can support firms that are more specialised in producing intermediate products. Specialisation can lead to enhanced opportunities for cost reduction in goods production when the production of components of intermediate goods can be routinized or the components of final products mechanised or automated, for example. The gains from specialisation extend to the production of services as well. (Citation2009:117)

The specialisation in production confers several external effects that are beneficial to urban production. Productivity gains can be realised through specialisation, lowered transaction costs and complementarities in production. The production in an urban setting allows sharing easily, knowledge and mimicking as large numbers of other economic actors congregate (Quigley, Citation2009). The externalities arising from lower transaction costs and better complementarities in production can emerge because larger urban scale can facilitate better matches between worker skills and job requirements or between intermediate goods and the production requirements for final output.

The economies of scale/agglomeration economies relate to the efficiencies that result from larger units of production. According to Duranton (Citation2009) three main mechanisms explain the existence of increasing returns in cities:

A larger city allows for a more efficient sharing of indivisible facilities (such as local infrastructure), risks and the gains from variety and specialisation. For instance, a larger city makes it easier to recoup the cost of infrastructure or, for specialised input providers, to pay a fixed cost of entry. This view is explained by McGranahan et al., (Citation2009) and Turok (Citation2012), indicating that larger firms can spread their fixed costs (rent, rates, research and development, etc.) over a larger volume of output and buy their inputs at lower prices.

A larger city allows for better matching between employers and employees, buyers and suppliers, partners in joint projects, or entrepreneurs and financiers. This can occur through both a higher probability of finding a match and a better quality of matches when they occur.

A larger city can facilitate learning about new technologies, market evolutions or new forms of organisation. More frequent direct interactions between economic agents in a city can thus favour the creation, diffusion and accumulation of knowledge. In Quigley (Citation2009), the effects of aggregate levels of schooling in urban areas on aggregate output may be distinguished from the effects of individuals’ schooling on their individual earnings. Productivity spillovers – educated or skilled workers increasing the productivity of other workers – may arise in denser spatial environments regardless of whether the urban industrial structure is diversified or specialised.

There are two important assumptions underlying the economic growth due to specialisation and the gains of scale economies in urban areas (McGranahan et al., Citation2009):

Urban areas give firms access to a bigger and better range of shared services and infrastructure, such as more frequent transport connections to customers and suppliers.

Firms benefit from the superior flows of information and knowledge in cities, promoting more learning, creativity and innovation, and resulting in more valuable products, processes and services.

Overall, economic growth effects of the respective agglomeration forces and congestion effects will depend on the speed of urbanisation (Christiansen et al., Citation2013). Managing of the urbanisation process is an important part of nurturing economic growth; while neglecting cities – even in countries in which the level of urbanisation is low – can impose heavy costs (Annez & Buckley, Citation2009).

2.2. Developing economies' relational pattern

Scholars have argued that urbanisation in developing countries is not driven by economic growth as was the case in the developed economies. In the former, high rates of urbanisation incommensurate with economic growth rates have been witnessed in the recent past, leading to the so-called ‘urbanisation of poverty’ (see for instance Singh, Citation1992; Piel, Citation1997; Ravallion, Citation2002). Two theories have been advanced to explain this pattern: the urban bias theory and the dependence theory (see Bradshaw, Citation1987). The urban bias theory posits that developing economies’ governments favour urban areas through public policy by concentrating economic activities and infrastructural, social and institutional services in urban areas. This attracts people from rural areas who migrate to urban areas with the hope to enjoy the good life there. However, the good life requires money, which the urban migrants cannot get since there is no commensurate economic growth to generate employment opportunities and hence income.

China, on the other hand, has pursued the reverse of urban bias theory by implementing anti-urbanisation policies that include the following (Chan, Citation1992):

Mass relocation of the urban population to the countryside.

Bans on rural to urban migration.

Suppression of urban consumption.

Rural industrialisation programmes.

Hence, today China is the only country that is rapidly industrialising without generating commensurate increase in urbanisation rates. Other developing economies including SSA countries do not follow this policy, and hence the urban bias theory is likely to explain their economic development and urbanisation relational patterns.

Dependency theory, on the other hand, postulates that developing economies are dependent on foreign aid, foreign direct investments. These do not involve any technological development, thereby establishing no significant forward and backward linkages within an economy.

The main focus of this study is to establish what theoretical patterns explain the relationship between economic growth and urban development in SSA countries. Is it the modernisation theory or the urban bias/dependency theory?

3. Data and methods

In this study, we use panel data to graphically portray the relational patterns between urbanisation and GDP in each SSA country over the period 1980–2012. presents a summary of the SSA countries we have considered. To reflect the economic diversity within SSA, the countries considered were divided into three categories:

SSA countries with per-capita GDP over US$3000.

SSA countries with per-capita GDP of US$1000–3000.

SSA countries with per-capita GDP below US$1000.

Table 1. Scope of countries considered in the analysis.

For purposes of international comparisons a few countries from emerging and developed economies were also considered.

Data on both the GDP per capita and urbanisation growth was obtained for each individual country from the World Bank's World Development Indicators online database.Footnote1 The raw datasets were transformed into indicators to enable temporal (1980–2012) and factor (urbanisation and economic growth) comparisons and graphical sketching of relational patterns.

The indicators were developed as follow. Each country's data were re-based to the year 1980 so that the value for 1980 = 100. The values for other years were generated as quantum indices of the 1980 values. For example, if GDP per capita was 1750 in 1980 and 1950 for 1981, the indices would be as follows: 1980 = 100; 1981 = 1950/1750 × 100 = 111.429. The same process was followed for the urbanisation rates. Therefore the indices were constructed so as to give them a single base value and trends that are comparable in a single graph. Thereafter, line graphs relating annual GDP and annual urbanisation growth rates for the period under study were charted for each country under consideration. The results of this endeavour are presented in the next section. Note that the graphs show the percentage of population living in urban areas, compared with real per-capita GDP in constant prices (chain series). Both time series are indexed to 100 in the initial year.

4. Observed relational patterns in sub-Saharan Africa

After charting the relational pattern graph for each SSA country, as already explained, comparisons were made among the countries of study and three common trends were identified:

Urbanisation with economic growth (economic growth and urbanisation are closely related):

with the GDP rate higher than the rate of urbanisation (Category 1), or

with the GDP rate lower than the rate of urbanisation (Category 2).

Urbanisation without growth (urbanisation and GDP growth rates are not closely related) (Category 3).

Details of these trending relational patterns are given in the following.

4.1. Urbanisation with economic growth (economic growth and urbanisation are closely related)

4.1.1. Category 1: the GDP rate is higher than the rate of urbanisation

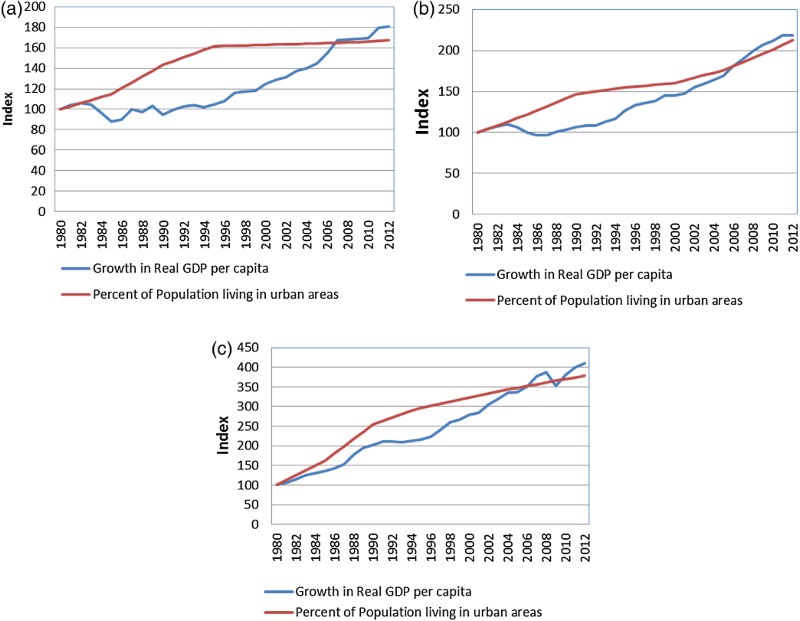

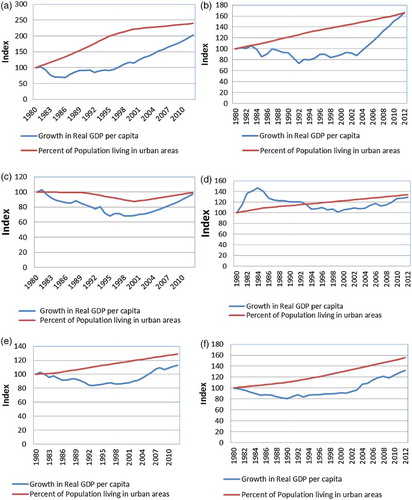

In Botswana, Uganda and Sudan the rates of real GDP growth have recently surpassed those of urbanisation. Some of the SSA countries may have encountered reversals in urbanisation rates. Given the rapid growth rates, the challenges of urbanisation might be modest in these countries compared with other SSA countries ().

4.1.2. Category 2: the GDP rate is lower than the rate of urbanisation

There are SSA countries where urbanisation rates are slightly higher than the rates of real GDP per capita. These countries include Zambia, D.R. Congo, Mozambique, Ethiopia, South Africa and Namibia ().

4.2. Urbanisation without growth (urbanisation and GDP growth rates are not closely related)

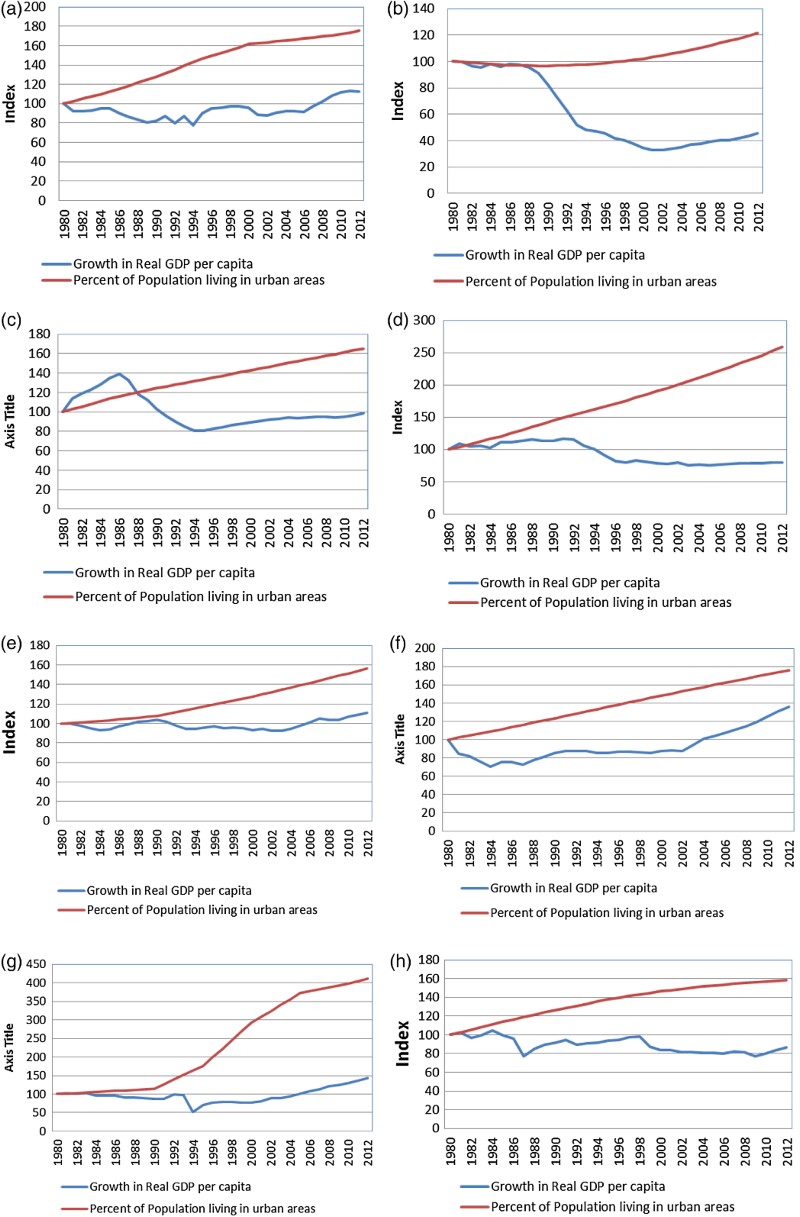

Finally, there are SSA countries where the gap between urbanisation rates and the rates of growth for real GDP per capita is widening. This is the classical trend in developing countries involving urbanisation without economic growth. This observation fits into the traditional debate on the relationship between urbanisation and economic growth in some African countries on whether urbanisation levels are excessive since it could be sustained by the rates of current GDP growth (Bertinelli & Strobl Citation2003; Henderson, Citation2003).The countries in this category include Malawi, Burundi, Kenya, Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda and to a small extent South Africa ().

5. Comparison with other world economies

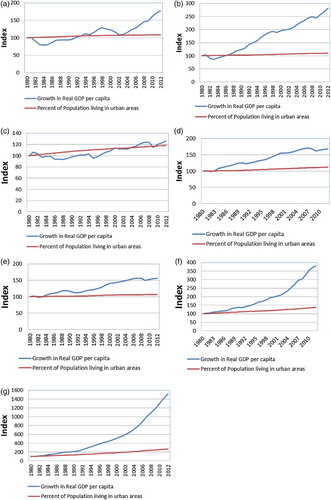

The historical patterns in SSA where urbanisation exceeds GDP growth rates bear similarities with those of Brazil, Mexico and Uruguay, which are the relatively more developed economies today. However, the historical patterns in SSA reflecting gaps between urbanisation and real GDP growth contrast patterns of the western countries and the emerging economies of India and China. In the United States, urbanisation rates and per-capita income moved together until about 1940, when urbanisation reached close to 60%; thereafter, per-capita income expanded much more rapidly (Tamang, Citation2013). In India and China, the transition was experienced in the 1960s. Presumably, in the initial phases when urbanisation rates and per-capita income increase at roughly the same rates, productivity increases reflect shifting resources from lower productivity rural activities. In later phases, rapid productivity gains reflect mainly improvements within industries and services (Annez & Buckley, Citation2009) ().

6. Implications of observed relational patterns

By observing the relational patterns it becomes clear that over time urbanisation has been growing faster than economic growth, leading to the conclusion that urbanisation in SSA has not been driven by economic growth. The classical developing country situation is represented by the Category 3 countries (i.e. urbanisation without economic growth). For these countries, the greater challenge in urbanisation lies in introducing policy measures necessary to attain rapid economic growth.

The graphical patterns tend to confirm the findings of Annez & Buckley (Citation2009) that most of the countries experiencing urbanisation without growth are small African countries at low levels of development. This has come to be termed ‘pathological urbanisation’ – substantial structural population shifts without growth – a phenomenon which is not common to the patterns in the rest of the world. Fundamentally, these urbanisation patterns tend to reflect problems elsewhere in the economy (Annez & Buckley, Citation2009).

This classical trend aside, new trends also are emerging. There is the pattern where economic growth recently surpassed urbanisation and the pattern where economic growth is closing on urbanisation. These patterns both imply urbanisation with economic growth. It is important to note certain time points. For instance, in the Category 1 observable patterns GDP surpassed urbanisation at more or less the same time (around 2006), thereby establishing a common trend that implies a common economic phenomenon. On the other hand, countries with Category 2 observable patterns are most likely to join their Category 1 counterparts in the near future.

Category 1 and Category 2 relational patterns implying urbanisation with growth conform to the notion that cities provide large efficiency benefits because the city network effects stimulate economic growth. The network effects spur economic growth and productivity (Dobbs et al., Citation2011). Existing urban inefficiencies do not imply that cities are less efficient than their rural alternatives: the very success of cities in developing countries points to the opposite. However suboptimal they may be, cities typically offer higher returns and better long-term opportunities than other areas (Duranton, Citation2009). A city plays a very important role in the economy, as the largest domestic market, the chief manufacturing centre, the primary trading connection with the rest of the world, and the seat of elites and often of the government (Storeygard, Citation2013).

Cities have traditionally functioned as sites of economic growth and crucibles of social and cultural progress. Urbanisation has been intimately bound up with the shift from predominantly agricultural economies to industrial and service-based economies. The outcome of urbanisation has been rising national productivity, higher average incomes and greater all-round prosperity (McGranahan et al., Citation2009).

Today, these cities generate about 50% of SSA's GDP. By 2025, this share is expected to reach 63%. Nevertheless, Africa's contribution to world GDP growth will remain at an estimated 2% (Dobbs et al., Citation2011).

On the other hand, a comparative look at the SSA countries reveals a certain critical point in their economic history. As with 2006 when GDP surpassed urbanisation in the SSA countries of Category 1 relational patterns, 1988–90 mark a turning point for many African countries across the board when their GDPs fell below urbanisation. For instance, in D.R. Congo the two variables remained on a par until the end of the 1980s when urbanisation shot above GDP. In Cameroon the GDP was higher than urbanisation until the late 1980s. The Kenyan story is similar to that of D.R. Congo, where GDP and urbanisation were more or less on a par until the late 1980s, while Zambia's case is similar to Cameroon's. This structural downturn may have been due to the impact of Structural Adjustment Policies preferred by the World Bank and IMF whose impacts were mainly felt in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In the developed North American economies of the USA and Canada, the relational patterns are the same where the GDP and urbanisation are relatively stable. They bear some similarity with the emerging economies of the South American countries Uruguay, Chile and Mexico. In both cases there is no wide gap between the two variables. In Uruguay the GDP fluctuates but has remained above urbanisation in the last two decades. In Chile the GDP has remained above urbanisation since the mid-1980s, while in Mexico it has remained so since the last decade.

The relational pattern of the big boys of Asia (China and India) is drastically different. In these countries there is a widening gap between the GDP and urbanisation, although the former remains higher. They are directly opposite to Category 3 patterns of SSA countries where the gap is widening but GDP falls far below. What is important, however, is that these SSA countries could learn lessons from Asia concerning the urban policies the two countries have implemented to sustain that pattern of urbanisation–economic growth.

7. Conclusion

The charting of relational patterns between urbanisation and economic growth has revealed something new about SSA; that contrary to the traditional belief, urbanisation is taking place with economic growth especially in countries like Botswana, Uganda and Sudan, on the one hand, and in Zambia, D.R. Congo, Mozambique, Ethiopia, South Africa and Namibia. However, the rest of the SSA countries considered (i.e. Malawi, Burundi, Kenya, Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda and to a small extent South Africa) still confirm the classical thesis that African countries are urbanising without the requisite power of economic growth. The implication of urbanisation is obvious; it leads to the generation of urban poverty. Therefore, the latter countries may learn from the urban policies of the emerging economies such as India and China that have been able to tame the trend that has been termed ‘the urbanisation of poverty’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Owiti A. K'Akumu http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0419-5437

Notes

1Urban population data are available online at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS, while economic growth data are available online at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD and http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG.

References

- Annez, PC, & Buckley RM, 2009. Urbanization and growth: Setting the context. In Spence, M, Annez, PC & Buckley, RM (Eds), Urbanization and growth. World Bank, Washington, DC (pp. 1–45).

- Becker, CM & Morrison AR, 1999. Urbanization in transforming economies. In Cheshire, P & Mills, ES (Eds.), Handbook of regional urban economics, North-Holland handbooks in economics, Elsevier, North-Holland ( Ch. 43, pp. 1172–1290).

- Bertinelli, L & Strobl, E, 2003. Urbanization, urban concentration and economic growth in developing countries. CREDIT Research Paper, No. 03/14.

- Bloom, DE & Sachs, JD, 1998. Geography, demography, and economic growth in Africa. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1998(2), 207–295. doi: 10.2307/2534695

- Bradshaw, YW, 1987. Urbanization and underdevelopment: A global study of modernization, urban bias, and economic dependency. American Sociological Review 52(2), 224–239. doi: 10.2307/2095451

- Chan, KW, 1992. Economic growth strategy and urbanization policies in China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 16(2), 275–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.1992.tb00173.x

- Christiansen, L, Gindelsky, M & Remi Jedwab, R, 2013. The speed of urbanization and economic development: A comparison of industrial Europe and contemporary Africa. Manuscript Version of May 10th 2013.

- Cohen, B, 2006. Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technology in Society 28 (1–2), 63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2005.10.005

- Davis, K & Golden, HH, 1954. Urbanization and the development of pre-industrial areas. Economic Development and Cultural Change 3(1), 6–26. doi: 10.1086/449673

- Dobbs, R, Smit, S, Remes, J, Manyika, J, Roxburgh C & Restrepo, A, 2011. Urban world: Mapping the economic power of cities. McKinsey Global Institute, Seoul, London, New York.

- Duranton, G, 2009. Are cities engines of growth and prosperity for developing countries? In Spence, M, Clarke Annez, P & Buckley, RM (Eds.), Urbanization and growth: The International Bank for reconstruction and development. The World Bank, Washington, DC (pp. 67–113).

- Duranton, G, 2014. Growing through cities in developing countries. Policy Research Working Paper Series 6818, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Henderson, V, 2002. Urbanization in developing countries. The World Bank Research Observer 17(1), 89–112. doi: 10.1093/wbro/17.1.89

- Henderson, JV, 2003. The urbanization process and economic growth: The so-what question. Journal of Economic Growth 8(1), 47–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1022860800744

- Henderson, JV, Roberts, M & Storeygard, A, 2013. Is Urbanization in Sub-Saharan Africa different? Policy Research Working Paper Series 6481, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Hoselitz, BF, 1953. The role of cities in the economic growth of underdeveloped countries. Journal of Political Economy 61(3), 195–208. doi: 10.1086/257371

- Hoselitz, BF, 1957. Urbanization and economic growth in Asia. Economic Development and Cultural Change 6(1), 42–54. doi: 10.1086/449754

- Kuznets, S, 1973. Modern economic growth: Findings and reflections. The American Economic Review 63(3), 247–258.

- Marshall, A, 1890. Principles of economics. Macmillan and Co, London.

- McGranahan G, Mitlin, D, Satterthwaite, D, Tacoli, C & Turok, I, 2009. Africa's urban transition and the role of regional collaboration. Human Settlements Working paper Series Theme – Urban Change 5. International Institute for Environment and Development. December 2009.

- Piel, G, 1997. The Urbanization of Poverty Worldwide. Challenge 40(1), 58–68. doi: 10.1080/05775132.1997.11471951

- Preston, SH, 1979. Urban growth in developing countries: A demographic reappraisal. Population and Development Review 5(2), 195–215. doi: 10.2307/1971823

- Quigley, MJ, 2009. Urbanisation, agglomeration, and economic development. In Spence, M, Clarke Annez, P & Buckley, RM (Eds.), Urbanization and growth: The International Bank for reconstruction and development, The World Bank, Washington DC, (pp. 115–132).

- Ravallion, M, 2002. On the urbanization of poverty. Journal of Development Economics 68 (2), 435–442. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(02)00021-4

- Singh, A, 1992. Urbanisation, poverty and employment: the large metropolis in the third world. Contributions to Political Economy 11(1), 15–40.

- Storeygard, A, 2013. Farther on down the road. Transport costs, trade and urban growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Policy Research Working Paper 6444. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Tamang, P, 2013. Urbanization and economic growth: Investigating causality. Econometrics 1(3), 41–47.

- Turok, I, 2012. Securing the resurgence of African cities. Local Economy 28(2), 142–157. doi: 10.1177/0269094212469920