ABSTRACT

The social and political conditions within which artisans are required to work have shifted globally. The South African policy concern is to train bigger quantities and improve artisanal skills quality, while simultaneously providing more opportunities for young, black and women artisans. A concern for academia is how this shifting milieu will impact on our understanding of artisanal work and occupations and what implications should this have for further research. Using the concept of occupational boundaries, we investigate, at a micro level, real and perceived change to work in three artisanal trades. The study shows that while some elements have changed, the division of labour reinforces the traditional scope of artisanal work in relation to other occupational groups. The findings reconfirm the complex relationship between changes to work and the demand for skills, and importantly highlight the sociology of work as a critical but undervalued dimension in labour market analysis.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

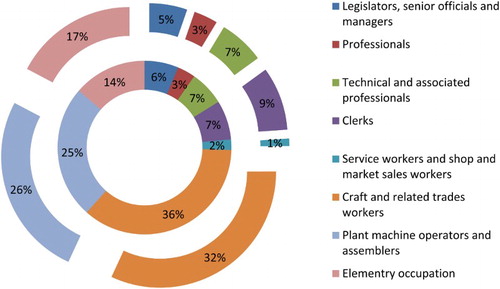

The social and political conditions, the milieu within which artisans are required to work, have shifted globally and in South Africa after apartheid. The policy concern is to train bigger quantities of artisans and improve the quality of artisanal skills, while at the same time opening up more opportunities for young, black and women artisans to shift historical trends of unequal access and success (RSA, Citation1998). Data on the employment of craft and related trade workers (the occupational group where artisanal employment is recorded), however, indicate that the labour market for artisans has been contracting between 2001 and 2012 (Bhorat et al., Citation2013). The same labour market data for the three sectors selected for this study confirm this trend, although for a shorter period of time (2008–13). Craft and related trade workers have seen a decline in proportional share of employment from 36% in 2008 to 32% in 2013 (). What makes this information noteworthy is that these sectors are historically strong employers of artisans.

Figure 1. Change in occupational group share of employment in mining, automotive and metals sectors, 2008–13.Note: inner circle, 2008; outer circle, 2013.

This causes a seeming disjuncture between policy-driven imperatives to increase and accelerate the production of artisans and the ability of the South African labour market to provide employment. Of course this analysis has limits. It does not take into account the opportunities for artisanal employment that might arise out of the informal labour market. It assumes that past employment trends are good predictors of future employment trends and it does not take into account the changing nature of work and how this would affect the nature of demand for artisanal skills.

Engaging with such concerns, this article presents findings from investigations into three artisanal trades in South Africa undergoing different facets of change. One is a new and emerging multidisciplinary field of practice recently recognised as a trade (mechatronics in the automotive sector), another is a traditional trade having to function in more technology-driven work contexts (electricians in the mining sector) and the third is a high-status trade also having to contend with the implications of increased application of technology (millwrights in the metals sector). Analysing changes to artisanal work and occupations across these cases re-affirms the complexity of the relationship between changes to work and the demand for skills, but also highlights that the sociological nature of work is a critical but undervalued dimension in our approaches to understanding our labour market.

The article is structured into three sections that should illustrate the bases upon which such assertions are made. First the conceptual frame, methodological and design considerations are presented. This shows how an occupational boundary was conceptualised as reflective of key elements comprising an occupational domain, as well as illustrating how the conceptual frame sets up the categories for analysis of change to the nature of artisanal work. The third section then presents the synthesised findings across the cases, and the final section draws together overarching insights for labour market research and analysis.

2. Boundaries as a lens to illuminate changes to the nature of artisanal work

Before we discuss boundaries, we need to briefly clarify what is meant by the term artisan or artisanal work. The most simplistic understanding of an artisan is an individual who is skilled at practicing a particular trade or handicraft, which became regulated, in most cases, by belonging to a guild (formal associationFootnote1). The training is characterised by vocational education combined with extensive practical training and experience. Although an artisan might do mainly manual work, it is recognised that this draws from an extensive technical and practical knowledge base combined with considerable experience in the practice of the relevant trade. Traditionally, the work of an artisan was associated with crafts, but later also included skilled manual labourers involved in manufacturing-related trades (Akoojee, Citation2013; Wedekind, Citation2013). This is the most dominant understanding of artisanal work in South Africa.

2.1. The tides of work change

Work will continue to change, but the increasing pace at which this is happening has led many to assert that we need to more regularly assess the implications for understanding and responding to the challenges of contemporary labour markets (Burke & Ng, Citation2006; Burns, Citation2007). Some of the key changes to work include increasing globalisation, the impact of technology (automation and mechanisation), the nature of employment (from full-time to shorter-term, contract-based jobs), the bigger role played by organisations (Muzio et al., Citation2011), less hierarchical and standardised forms of work organisation, and the identity and values of workers (Wildschut et al., Citation2015).

Maclean & Wilson (Citation2009) see the key change in artisanal work to particularly relate to a shift from a mix of 50% theory and 50% practical to one that is 80% theory and 20% practical, summarising that:

Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is currently faced with the challenges posed by the displacement of the traditionally strong focus upon manual work in favour of mental work, or at least the changing mixture of competencies required in the workplace … . (Maclean & Wilson, Citation2009, xcvii)

The point is simple: there are changes to work that can result in change to the occupational scope of practice and its associated knowledge and skills – the traditional boundaries of the occupational group as it were. It is thus imperative to engage critically with how work change translates to change for different levels of work. To capture and analyse such change in artisanal work, the project adopted the lens of ‘boundaries’ between occupational groups. Next we clarify how this boundary was conceptualised.

2.2. Conceptualising an occupational boundary

The concept of boundaries is well established and has been applied extensively to investigate various forms of sociological and institutional change (Lamont & Molnar, Citation2002). As this project focused on the ways in which boundaries between occupations are manifested in the work context, the conceptual frame was informed by studies on professions and work (Evetts, Citation2003) as well as science, disciplines and knowledge (Gieryn, Citation1983, Citation1999; Star & Griesemer, Citation1989).

2.2.1. Occupational boundaries and the world of work

Because the right to supply certain collections of skills, services and knowledge to society holds monetary and status rewards, it is not surprising that there will be competition over these domains. Occupations constantly try and expand, either vertically or horizontally, their claims towards rights to offer a collection of skills, knowledge and services (also referred to as jurisdictional claimsFootnote2) in the labour market. Established professions such as medicine, law and engineering are examples of occupations that have been successful in establishing and defending their occupational jurisdictions. Occupational boundaries are thus critical in establishing control over knowledge and/or practice domains in a labour market. Fournier (Citation2000) indicates two processes crucial towards establishing such control:

the constitution of an independent and self-contained field of knowledge as the basis upon which to claim/build authority and exclusivity, as well as

the labour of division which goes into erecting and maintaining boundaries between the professions and various other groups (other occupational groups, clients and/lay persons, and the market).

As professions are occupations that have been successful over an extended period of time in claiming exclusive rights to offer certain services and perform certain tasks for society, the contestation of occupational domains is an issue explored extensively in the sociology of professions and work literature. Authors such as Abott (Citation1988, Citation1995) and Freidson (Citation1989, Citation2001) are notable in this regard. However, with professional boundaries increasingly coming under pressure because of extensive changes in the world of work today, interest has renewed around the issue of occupational jurisdiction.

While this discussion tends to predominate in the area of healthcare (Hopkins et al., Citation1995; Barrett et al, Citation2007; Martin et al, Citation2009; Wakefield et al., Citation2009; Motulsky et al., Citation2011; Kroezen et al., Citation2013; Miller, Citation2014) and social work (Welbourne, Citation2009; Heite, Citation2012), increasingly a wider array of fields and occupations is being considered; for example, journalism (Lewis, Citation2012) and academia (McMillan, Citation2011). Highlighting the gap that this study aims to address, issues surrounding changes to knowledge, competencies and skills have received much attention in the ‘traditional’ professions, but artisanal occupations have seldom been the focus of such investigation. Vallas’ (Citation2001a) work on engineers and skilled manual workers is one of such few.

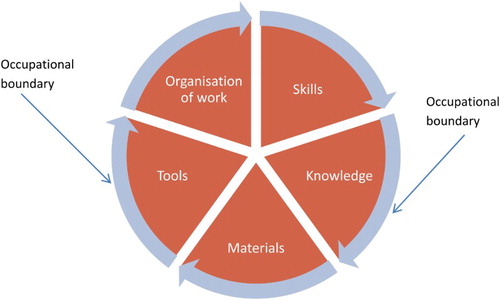

Based on this literature, we draw a very basic premise that an occupational boundary can be understood as a distinction between different types of occupations. This is a distinction that consists of observable elements of a domain of work as well as the conceptual distinctions informing the association of a domain of work with a specific occupational group. Lewis (Citation2012:7) makes a similar assertion that jurisdiction is about ‘displaying what a profession or occupation knows (its system of abstract knowledge) and connecting that to what the profession or occupation does (its labour practices)’. We conceptualise that occupational boundaries change in relation to shifts in these two aspects. To represent the system of abstract knowledge, we select the concepts of skills and knowledge; to represent the labour practices, we select the concepts of tools, materials and organisation of work. Together, these elements are selected as delineating the boundary between occupations ().

Some of these terms are contested in the literature, requiring clarification on how these are used in this study. A purely practical distinction is adopted in using the terms knowledge and skills respectively, although we acknowledge that there is a relation between the two that might make distinguishing between them inappropriate in some instances. We only wanted to differentiate between changes to expectations of what artisans should be able to do (skill) and what they must know (knowledge).Footnote3

The literature on work as a labour process further suggests that occupational boundary rules are established by the relation between materials, tools and organisation of work. As illustrated in Gamble (Citation2015:8):

work can be described as a labour process that comes about through the relation between the division of labour (or the way work is organised), the tools or technology used and the materials used … this three-way relation was the traditional way of separating one trade from another … [and] the value of understanding work in this manner remains undisputed.

Others would add the final product as another important element distinguishing the scope of work of different occupations. However, as the occupational groups under consideration for this study worked towards the production of the same ‘product’, we did not adopt this further distinction.

We argue that using occupational boundaries in the way conceptualised here, incorporating individuals’ understanding of the skills and knowledge associated with their work, can offer additional insight into work change and its implications. Individual and group perceptions and attitudes around work are an often neglected area of investigation, but they clearly have a bearing on the labour market (Mncwango et al., Citation2015).

2.3. A note on methods and design

The project was designed as a set of case studies of key occupational groups in a focus field of practice and focus industry sector, combining primary and secondary research. We selected this approach because case studies make it possible to ‘analyse at a concrete level the interactions among changing markets, changing technology, changing labour supplies, changing skill requirements, and changing educational processes’ (Bailey, Citation1990:3). This involved occupation-specific literature reviews, organisational document reviews, labour market demand and supply analysis, and individual interviews. Semi-structured interview schedules were designed to collect a broad range of data related to occupational milieus and labour markets, boundary work, boundary objects and identity, although respondents were allowed to raise additional issues. The interviews were conducted in boardrooms, training centres and workshops on company premises, designed to last between 30 and 60 minutes. For accuracy purposes, interviews were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The computer program NVivo (version 11) was used to code the qualitative data. Essentially there were three dimensions of coding. The coding per case was done by at least two researchers to enhance reliability. Firstly, the descriptive data were classified, linking demographic data to each transcript, so that when quotes were coded at a particular node/theme this information was included. This made it possible, for example, to search by race and case, whether there were identifiable differences in how occupational boundaries were contested. Secondly, we coded for instances where the elements constituting an occupational domain were mentioned. At this level we only coded for whether a particular piece of narrative claimed/indicated change in the field of practice. Here for example, mentioning of different technologies used in their work would count as indicative of change to the tools used. Lastly, we coded for whether the quote indicated perceived change to the particular element in terms of the work of an artisan, technician or professional.

2.3.1. Reflecting on the sample

The sample consisted of 94 respondents across five categories: Human Resources (HR) practitioners, engineers, technicians, artisans and apprentices ().

Table 1. Sample distribution by case and category (n = 94).

The sample is dominated by artisans (40%). However, if we combine the categories of apprentices and qualified artisans, individuals involved in artisanal work and training make up the majority of the sample (54%). Engineers also make up a substantial proportion (24%). The cases each reflect concentration in the province where the sector activities are concentrated (automotive sector in the Eastern Cape area, metals sector in Gauteng and the mining sector in the North-West).

2.3.2. Three fields of practice

It is important to have background on the cases and the particular dimensions of change they were experiencing at the time of the study, before the cross-case analysis.

2.3.2.1. Case 1: Mechatronics in the automotive sector

Mechatronics engineering includes the study of electronics, software and mechanical engineering in the design and manufacture of products and processes. Its application combines highly technical and knowledge-intensive fields, such as traditional electrical, electronic, mechanical and computer engineering. It is essentially about the computer control of an electro-mechanical system (Wolf & Luckett, Citation2013), ‘affording intelligent functions and features’ (Lyshevski, Citation2002:197) that were not possible or cost-effective before. Mechatronics is seen as an ideal area of expertise central to modern vehicle manufacturing (Garisch & Meyer, Citation2015), and thus the automotive sector was selected as the empirical focus. In South Africa, a dedicated mechatronics qualification at the vocational skills level has recently been instituted, along with recognition as an artisanal trade (DHET, Citation2012).

The main occupational groups working in the mechatronics function area were found to be engineering professionals, technicians, artisans and mechatronics apprentices. Engineering professionals, technicians and artisans are the current mechatronics functionaries although they would have been trained as generalists. One can thus make a distinction between artisans who are working in the area but qualified in a traditional trade (electrical or fitting and turning) and the mechatronics apprentices being trained as the ideal functionaries to work in this field at the intermediate skills level. This state of affairs points to an interesting supply and demand context rife with potential for occupational boundary contestation and shifting.

2.3.2.2. Case 2: Millwrights in the metals sector

The work of millwrights includes the construction and maintenance of heavy machinery used in industry. Millwrights must be able to dismantle and overhaul machinery and equipment, requiring the use of hand and power tools, and to direct workers who are engaged in these activities. Also, they need to understand blueprints and technical instructions in order to assemble machinery. The millwright may also need to use lathes, milling machines and grinders to make customised parts or repairs. Electrical installation of equipment also forms part of their responsibilities, as does knowledge of electronics because of the increasingly automated nature of industrial machinery.

Other skills such as a good understanding of fluid mechanics (hydraulics and pneumatics), and of all of the components involved in these processes including valves, cylinders, pumps and compressors, might also be required. Modern standards of practice for millwrights direct the kinds of skill requirements, such as working within precise limits or standards of accuracy with a wide array of precision tools. The main occupational groups functioning in this area were found to be technicians, millwrights and other generalist artisans (fitters and turners and electricians). As the millwright’s trade has traditionally enjoyed a high status in comparison with other trades, we anticipated that a certain level of boundary contestation would be present between millwrights and generalist artisans. Over the last few years, the work of millwrights has been viewed as influenced heavily by changes to the electrical component of their work.

2.3.2.2 Case 3: Electricians in the mining sector

Electricians working with heavy currents generally specialise in construction of new structures and maintenance work (or both). In new structure development, electricians primarily install wiring into new buildings, be they residential, commercial or industrial. In maintenance work, electricians maintain, upgrade or repair existing electrical systems. Electricians who work with light currents will typically be involved in electronic engineering where the systems are computer based, as opposed to electrical engineering work.

This case is interested in electricians in the mining sector; typically referred to as industrial electricians. Their job involves testing, repairing and maintaining electrical equipment. While basic electrical knowledge is essential to excel within this industry, those electricians who are exposed to newer technologies involving computer-based systems will have an advantage. Within the mining sector, electrical training includes baseline risk assessment and basic electricity, panel wiring and circuits, fault finding and installations, as well as components that make use of newer technologies such as electronics and programmable logic controllers (PLCs). The main groups functioning in this field of practice appear to be electrical apprentices, qualified artisans and electrical engineering professionals. In this case the position of a technician was not prominent. The main change affecting the work of an electrician appears to be the shift from electrical to electronic work.

3. The nature of artisanal work in three industry sectors

This section presents findings on artisanal work change across the trades selected as foci for this investigation. Three distinct trends can be identified in relation to the elements conceptualised as reflecting the occupational domain. Firstly, we find real and perceived change to the skills and knowledge required by artisans. Secondly, while our evidence also suggests that the tools for artisanal work have changed, with implications for the manual dimension of their work, manual ability remains key in constructing the occupational identity. Lastly, although the relation between materials and tools for artisanal work has shifted, the organisation of work plays a critical role in reinforcing the traditional scope of artisanal work in relation to other occupational groups. The evidence for these assertions is described in the following.

3.1. Real and perceived change to knowledge and skills requirements

First we find evidence for expanded skills requirements, expectations that artisans should have more generic skills not traditionally associated with artisanal work. Artisans are increasingly required to plan their work and organise and manage their time, maintenance-related in particular. The timeous identification and procurement of parts required for maintenance jobs emerged as critical in defining artisanal work at present. Another general trend in a similar vein comprises the re-ordering of parts for those replaced in breakdown situations. These practices stand in stark contrast to the ‘old-school era’ where artisans simply arrived at the breakdown scene with their toolbox and walked away upon completion of the repair job, with all administration-related aspects being left to the supervisor and engineer for processing. Additional administrative responsibilities comprise the compiling and presenting of breakdown reports (in a team context) as well as hand-over reports upon completion of shifts. Indicative that this is seen as traditionally outside the scope of artisanal work, the following respondent asserts ‘the slightest administration work you give them to do; like when they do my maintenance schedules … that becomes like a nightmare to them’ (HR professional, MechCase).

Not only are the skills required for artisanal work perceived to have expanded, but the increasing incorporation of automation technologies are seen to elevate their work in terms of knowledge and skills required. Artisans are expected to apply and be proficient in understanding implications of new technologies. In this regard, the PLC, supervisory control and data acquisition systems and, especially in the automotive sector, robots played a big role in changing the nature of artisanal work. As illustrated by the following respondent:

the type of person or artisan that we need in th[is] type of environment is a person that is multi-functional – whether it’s robotics or systems, mechanical, electrical or whatever … . (HR professional, MechCase)

Another respondent concurs: ‘your basic electrician does not cut it anymore because he now also has to service your robot … he has to understand basic PLCs and programming because all of the jigs and fixtures are nowadays running off PLCs’ (engineer, MechCase). The increased expectation of artisans to engage with abstract knowledge and analyse different technologies is clear, as indicated in the following:

if, in my work, I read about something or somebody comes … with a new product or a new type of machine, I have to research it and evaluate it … can it work or can it not work and if it makes sense … (Artisan, ElecCase)

Another respondent confirms this sentiment:

… [artisans] need to be able to read a little bit more … it’s no longer about you working with your hands it’s also more about reading papers about different technologies … to understand what is happening in those areas. (HR professional, ElecCase)

In the millwrights’ case this trend is exemplified in the incorporation of PLCs as a significant change to production processes, which were previously manually controlled. This requires all millwrights to be more technologically skilled in order to remain relevant and the change is seen to expand their work to include more electronic and computerised activities. Some of such changes, as well as the pace of change, is alluded to by this respondent:

on the electrical side new stuff that is coming out like PLC, drives, soft starters, and normally after three years some of the stuff they change, they come with a new design, new software … . (Artisan, MillCase)

The same implications apply for the work of electricians. They are expected to be proficient in working with new technologies, where a greater understanding of electronics is a key driver of change. As indicated by one respondent:

what we were actually teaching the guys just a year ago it’s totally different … We’ve got a lot more of electronics on the system than before … They have to be more technically skilled … . (HR professional, ElecCase)

The mechatronics case is probably the best example of the traditional notion that artisans having more practical as opposed to theoretical knowledge is changing. This new qualification promises an individual who has a broader and higher level of knowledge and skills in comparison with traditionally trained artisans. This is causing contestation and perceived changes to the scope and level of artisanal work and thus also the demarcation of the work of technicians in this field of practice. This is illustrated by the following narratives:

companies are going to be forced to recognise these people at a higher level because of what they are going to be able to do – they are definitely not an artisan anymore … that’s why we changed our entry requirements and made it to a higher level just to make sure that we got people who … are analytical thinkers. (HR professional, MechCase)

the artisan and technician will fall away as you’ll have the mechatronics guy with automation knowledge and the practical training to do both those jobs … the mechanical work and the electrical work that the artisan is doing and automation what the technician is doing. (Artisan, MechCase)

Reviewing these data suggests both real and perceived change to the knowledge and skills expected to be held by artisans. There is evidence for a greater scope of skills as well as changes to the level of knowledge and skills traditionally expected of artisans. This supports Maclean & Wilson (Citation2009), who assert that there will be changes to the required mix between artisanal skills and knowledge. The findings in relation to tools and materials build on these insights.

3.2. Tools have changed with implication for the manual dimension of artisanal work

The increased computerisation and automation of production processes has not only affected required artisanal knowledge and skills. It has reduced artisan’s involvement in direct production, combining/eliminating certain jobs/tasks. Because such technologies impact on the tools used to perform work, it shifts the manual component traditionally viewed as paramount to describing artisanal work, as this respondent indicates: ‘ … nowadays, a lot of companies, they are no longer using this manual stuff – they are going to PLC and drive … ’ (artisan, MillCase). Another respondent confirms:

In the old stage you just started say, a pump, by hand … you had to call somebody out to start another pump, or switch it off … But now it’s automated, you have a PLC, a computer system and it reads the demand, and as the demand grows another pumps starts automatically … It’s automation … . (Artisan, MillCase)

There are two implications – this distances the artisan from the material he/she works with as well as shifting the manual aspect of their work. While diagnostic and fault-finding skills so critical to describing the work of an artisan might remain the same, technology alters the relation between the materials and tools used for artisanal work. This was strongly illustrated in the electricians’ case. The ‘material’ that electricians work with is electricity and this has not changed. While technology has automated and provided different tools for problem-solving, the material and logic underpinning decision-making are seen as remaining the same – as indicated by this respondent:

there’s been technology that came through … it brought a bit of new dimensions, but … a lot of stuff still remains the same, there’s going to be only modifications here and there but it doesn’t change the basics of the trade itself. (Artisan, ElecCase)

This view is supported by another respondent in the same case, when asked what impact technological changes have had in the electrical field:

Not in the mining industry, no. We’re still there to make sure that the machines are operating. Whether it’s new technology or old technology, I don’t think that really has changed, the essence of what we need to do and how. (Engineer, ElecCase)

Another respondent agrees that the logic remains the same although the tools to do the job might change: ‘if the electrician knows the basic principles of an electrician, the principle remain the same, but the technology advances … the equipment changes’ (HR professional, ElecCase).

While the logic might remain intact, the relation between materials, tools and the artisan is affected. Instead of going to the actual location of a problem, the PLC enables the remote identification, and oftentimes fixing, of a fault. The following respondent asserts:

… we’ve got a lot more of electronics on the system than before so while in the past you know you needed to mechanically or use your strength … these days you can do it remotely … . (HR professional, ElecCase)

New technologies have the potential to shift the traditional relation between the artisan, materials and tools, but it can also affect the constructed and delineated scope of artisanal work in relation to other occupational groups. In review of the narratives, PLCs are recognised as potential expanders of the work of artisans and affected occupational groups are trying to maintain their occupational domains. For example, this respondent asserts that:

the millwright normally they want to learn more, [but] for job security the [technicians] do not allow them … on the PLC’s, we put passwords on them, they do not inform them of changes we make in the systems [or] give them training in what has been changed … . (Engineer, MillCase)

Technicians try to maintain this boundary discursively in claiming PLC work to be outside the normal, maintenance functions associated with artisanal work; for example,

my core job here … is I assist the robot programmers and the robots … I don’t sit and maintain the robots on a daily basis. I do the initial installation – complete turnkey which is the integration between the robot, the PLC, the SCADA [supervisory control and data acquisition] system … I plan and manage … I do all the costing, the planning, the purchasing … I have to give daily feedback on that but I’ve had people doing all the work – the actual installation. (Technician, MechCase)

Mechatronics apprentices contest the claims of technicians in their field, constructing their work to be above the level of the traditional artisans, and here PLC work and distancing from maintenance work appear key in such claims:

the artisan … he will be a hands-on person … he will go in with his spanner, screwdrivers. He will physically work with the machine. On my side, I will plug in my laptop, do a diagnostic – where is the problem? What needs to be replaced … . I also make slight programme changes on PLCs, modify present operations, HMIs (human machine interface systems), setting your drives … . (Apprentice, MechCase)

The symbolic importance of PLC work for successfully contesting the occupational boundary has clearly been recognised, as illustrated in the narrative of another mechatronics apprentice: ‘a guy that can sort out this PLC problem it’s almost like he’s performing magic, because people can’t see what he’s doing. But with a fitter you can see the guy is grinding … ’ (apprentice, MechCase).

This highlights an interesting dimension of technology and tools and how these are used to contest the elements belonging to a particular occupational domain. It reminds us of Gieryn’s (Citation1999) assertion that the content of occupational jurisdiction is not naturally assigned. Rather, recognising an object (in this case PLC work) to belong within an occupational scope of practice is the product of a successful process of claiming and defending an occupational boundary.

A final insight in this regard is that while the manual dimension of artisanal work is shifting, manual abilities continue to construct the occupational identity, although less so in the mechatronics case. This is illustrated by the following artisans:

The artisan is the one that’s working with the tools … he’s more hands-on … . (MillCase)

I’d say practical is the most important aspect of an artisan [one] must have the practical knowledge to do his job the way he’s supposed to do, if he does not have the practical knowledge then the theoretical aspect of it does not count. (ElecCase)

… the one [engineer] sits with all the concept knowledge and the other [artisan] sits with all the practical know how. (MechCase)

From such data it appears that the incorporation of increasingly computerised, mechanised and automated production processes has shifted the relation between the tools, materials and artisans themselves, and has also altered the manual dimension of their work. This section also highlighted that such change has the potential to alter the delineated scope of artisanal work in relation to other occupational groups. This is in line with Gamble’s (Citation2015:8) assertion that ‘advances in technology and materials have broken down many of the original trade demarcations’.

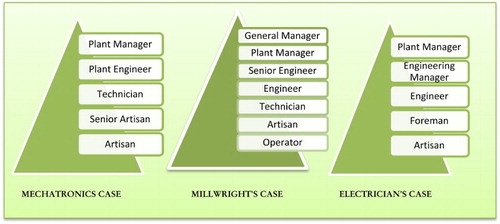

3.3. Organisation of work reinforces traditional occupational boundaries

In addition to changes to the division of labour that might result from technological change, the tendency towards greater integration and team-oriented settings is argued to describe the future workplace. Individuals are increasingly required to work across disciplinary boundaries, as well as those that are considered to be skilled across disciplines (Friman, Citation2010). It was interesting to find that while the literature suggests flatter organisational structures (Heerwagen et al., Citation2010), this trend did not bear out in the cases under investigation for this study. In all three cases work continues to be organised hierarchically and the scope of artisanal work in relation to other occupational groups is clearly set out and reinforced (see ). Thus, while artisanal work is perceived to have expanded in many ways, and elevated in some, occupational boundaries remain important for work organisation.

Figure 3. Occupational hierarchies across cases as an illustration of accepted occupational boundaries.

We found that the organisation of work continues to play a prominent role in maintaining and defining the level of artisanal work, determining who performs which tasks and who is responsible for which functions. Work is organised around clearly determined tasks, as shown by this respondent:

the system technicians … are the guys looking after the PLC. And then below them are the instrumentation technicians … looking at lower levels … the valves and temperature control … Below them we get the millwrights. And then below the millwrights you actually get the fitters and the rest of them. (Engineer, MillCase)

Organograms, work schedules and breakdown protocols reinforce the occupational domains. Breakdowns function as key sites of boundary contestation bringing up jurisdictional claims, where it is commonplace for artisans, technicians or engineers to indicate ‘this is not my work’. As illustrated by the following response: ‘I’m a technician, I’m not going to take that motor out because that’s a job for an artisan’ (technician, MechCase). Strict escalation protocols also re-affirm the hierarchy, as is shown in the following quotes:

with breakdowns the millwright is the first on site. If he can’t sort an electrical problem out, he escalates it to a technician after one hour. If the technician can’t sort it out he escalates it to a technologist after one hour. (Technician, MillCase)

While the electrical case had less stringent timescales, the organisation of work is similar, ‘that’s [fault finding] an artisan’s job and a foreman’s job … if it comes to a stage where it does get tricky … the engineer in electrical for instance will come and say what’s going on can I help, have you checked it?’ (Artisan, ElecCase)

While it is not surprising to find that the way work is organised will reinforce occupational tasks and job descriptions, it is surprising that perceived elevation and expansion of knowledge and skills required for artisanal work exists alongside the traditional division of labour.Footnote4 This finding importantly illustrates how occupational domains can still be successfully contested amidst real change to work, as is illustrated by the narrative of this apprentice:

… maths and science help you in a way you do calculations but it’s not an everyday thing, it’s not like engineer … but they teach you a way of thinking … help you into resolving solutions … so you don’t apply them but you apply them indirectly … . (Apprentice, ElecCase)

The success of professional groups in connecting their labour practices with an abstract system of knowledge is clear; as this respondent asserts for artisans, mathematics and science knowledge ‘it’s not an everyday thing’ – ‘it’ s not like engineers’. Considered in relation to the conceptual frame, the finding suggests that while we understand the organisation of work, materials and tools to reflect the more tangible aspects of an occupational domain, there is indeed an interface and process of social construction that underpin the connection of these with the ‘less tangible’ elements of skill and knowledge. Thus, to better understand work change and implications for skills demand, sociological investigation that goes beyond a labour process focus will become more critical.

4. It is important to understand the nature of work

This article aimed to illustrate how work change can affect occupational scopes of knowledge and practice in diverging ways, with sometimes unanticipated outcomes for the real and perceived demand for related skills. The study findings contribute in two key ways. First it provides insight into a topic studied extensively in the literature on professions and work, but from a vantage point of an occupational group seldom the focus of such investigation. The findings also contribute to the South African literature on artisans, as this tends to focus on the quantitative identification of the demand for artisanal skills, rather than trying to understand the nature of that demand and how it changes (Wildschut et al., Citation2012).

Lastly, the findings highlight the importance of a sociological investigation into work and work change as important in understanding our labour market. This supports assertions by authors such as Gamble (Citation2015) and Wildschut et al. (Citation2015) that we need to focus more closely on understanding the complex and multi-layered contextual issues that impact quite critically on the nature and location of skills demand and supply. The findings remind us that work is more than just a labour process and that there is a sociological dimension which impacts on the labour market. As Burger et al. (Citation2015:38–9) note, ‘it is vital to move beyond the surface and explore how class categories [in this instance an occupational group] are perceived and used … especially in light of its potential role in mediating key economic and political benefits’. This is in line with the assertions of Vallas (Citation2001b) that there are ‘social relations, normative codes and organisational structures that inform the behaviour, experience, and identities of people during the course of their working lives’ and these are clearly important for understanding, and attempting to intervene in, our labour market.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1South African artisans do not benefit from an overarching body for regulation.

2See seminal authors such as Abott (Citation1988) and Freidson (Citation1989) referred to later.

3The debate on differentiating between knowing that and knowing how is clearly outside the scope of this article. Theorists such as Ryle (Citation1949) and Russell (Citation1912) are notable in this regard.

4It would be important for further study in this area to investigate whether this finding holds across a wider and different collection of trade types (non-engineering related specifically), as well as across company size.

References

- Abott, A, 1988. The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Abott, A, 1995. Boundaries of social work or social work of boundaries?: The social service review lecture. Social Service Review 69(4), 545–62. doi: 10.1086/604148

- Akoojee, S, 2013. South Africa. In Smith, E & Kemmis, R (Eds.), Towards a model apprenticeship framework - A comparative analysis of national apprenticeship systems. ILO; The World Bank, New Delhi.

- Bailey, T, 1990. Changes in the nature and structure of work: Implications for skill requirements and skill formation. Publication prepared for VOCSERV, University of California, Berkeley.

- Barrett, M, Orlikowski, W, Oborn, E & Yates, J, 2007. Boundary relations: Technological objects and the restructuring of workplace boundaries. Working paper series 16/2007. Judge Business School, Cambridge.

- Bhorat, H, Goga, S & Stanwix, B, 2013. Occupational shifts and shortages: Skills challenges facing the South African economy, Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP) Report 1. Compress.dsl, Cape Town.

- Burger, R, Steenekamp, CL, Van Der Berg, S & Zoch, A, 2015. The emergent middle class in contemporary South Africa: Examining and comparing rival approaches. Development Southern Africa 32(1), 25–40. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2014.975336

- Burke, RJ & Ng, E, 2006. The changing nature of work and organizations: Implications for human resource management. Human Resource Management Review 16(2), 86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.006

- Burns, E, 2007. Positioning a post-professional approach to studying professions. New Zealand Sociology 22(1), 69–98.

- DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training), 2012. Skills Development Act, 1998 No. 839. Listing of occupations as trades for which artisan qualifications are required. August. Government Gazette No. 34666.

- Evetts, J, 2003. The sociological analysis of professionalism: Occupational change in the modern world. International Sociology 18(2), 395–415. doi: 10.1177/0268580903018002005

- Fournier, V, 2000. Boundary work and the (un-) making of the professions. In Malin, N, (Ed.), Professionalism, boundaries and the workplace. Routledge, London, 67–86.

- Freidson, E, 1989. Theory and the professions. Indiana Law Journal 64(3), 422–32.

- Freidson, E, 2001. Professionalism: The third logic. 1st edn. University of California, San Francisco, USA.

- Friman, M, 2010. Understanding boundary work through discourse theory: Inter/disciplines and interdisciplinarity. Science Studies 23(2), 5–19.

- Gamble, J, 2015. Work and qualifications futures for artisans and technicians. Synthesis report prepared for the DHET Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP). September.

- Garisch, C & Meyer, T, 2015. Mechatronics in the automotive sector in South Africa. Case study report for the Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP). February.

- Gieryn, TF, 1999. Cultural boundaries of science: Credibility on the line. University of Chicago Press, London.

- Gieryn, TF, 1983. Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: Strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. American Sociological Review 48(6), 781–95. doi: 10.2307/2095325

- Heerwagen, J, Kelly, K & Kampschroer, K, 2010. The changing nature of organisational, work and workplace. Whole building design guide – a program of the National Institute of Building Sciences, http://www.wbdg.org.resources/chngorgwork.php Accessed 5 May 2015.

- Heite, C, 2012. Setting and crossing boundaries: Professionalization of social work and social work professionalism. Social Work & Society 10(2). http://www.socwork.net/sws/article/view/334/671 Accessed 5 June 2015.

- Hopkins, A, Solomon, J & Abelson, J, 1995. Shifting boundaries in professional care. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 89(7), 364–71.

- Kroezen, M, van Dijk, L, Groenewegen, PP & Francke, AL, 2013. Knowledge claims, jurisdictional control and professional Status: the case of nurse prescribing. PloS One 8(10), e77279. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0077279 Accessed 5 June 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077279

- Lamont, M & Molnár, V, 2002. The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology 28, 167–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141107

- Lewis, SC, 2012. The tension between professional control and open participation: Journalism and its boundaries. Information, Communication & Society 15(6), 836–66. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.674150

- Lyshevski, SE, 2002. Mechatronic curriculum – Retrospect and prospect. Mechatronics 12(2), 195–205. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4158(01)00060-5

- Maclean, R & Wilson, D, (Eds.), 2009. International handbook of education for the changing world of work: Bridging academic and vocational learning, Vol. 1. Springer Science & Business Media, Dordrecht.

- Martin, GP, Currie, G & Finn, R, 2009. Reconfiguring or reproducing intra-professional boundaries? Specialist expertise, generalist knowledge and the ‘modernization’of the medical workforce. Social Science & Medicine 68(7), 1191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.006

- McMillan, J, 2011. What happens when the university meets the community? Service learning, boundary work and boundary workers. Teaching in Higher Education 16(5), 553–64. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.580839

- Miller, JH, 2014. Professionalism interrupted? Professionalism’s challenges to local knowledge in New Zealand Counselling. Current Sociology 62(1), 100–13. doi: 10.1177/0011392113513396

- Mncwango, B, Paterson, A, Ngandu, S & Visser, M, 2015. A study of attitudes to work: Synthesis of the evidence. Client Report prepared for the Department of Labour. HSRC, Pretoria.

- Motulsky, A, Sicotte, C, Lamothe, L, Winslade, N & Tamblyn, R, 2011. Electronic prescriptions and disruptions to the jurisdiction of community pharmacists. Social Science & Medicine 73(1), 121–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.009

- Muzio, D, Kirkpatrick, I & Kipping, M, 2011. Professions, organizations and the state: Applying the sociology of the professions to the case of management consultancy. Current Sociology 59(6), 805–24. doi: 10.1177/0011392111419750

- RSA (Republic of South Africa), 1998. Skills Development Act (No. 97 of 1998). Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Russell, B, 1912. The problems of philosophy. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Ryle, G, 1949. The concept of mind. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Star, SL & Griesemer, JR, 1989. Institutional ecology, translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science 19(3), 387–420. doi: 10.1177/030631289019003001

- Vallas, SP, 2001a. Symbolic boundaries and the new division of labor: Engineers, workers and the restructuring of factory life. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 18(1), 3–37. doi: 10.1016/S0276-5624(01)80021-4

- Vallas, SP, 2001b. Sociology of work and employment. 27 July. Oxford Bibliographies. http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756384/obo-9780199756384-0057.xml Accessed 5 October 2015. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199756384-0057

- Wakefield, A, Spilsbury, K, Atkin, K & McKenna, H, 2009. What work do assistant practitioners do and where do they fit in the nursing workforce? Nursing Times 106(12), 14–7.

- Wedekind, V, 2013. Rearranging the furniture? Shifting discourses on skills development and apprenticeship in South Africa. In Akoojee, S, Gonon, P, Hauschildt, U, & Hofmann, C (Eds.), Apprenticeship in a globalised world. Premises, promises and pitfalls. Reihe Bildung und Arbeitswelt, LIT, Münster.

- Welbourne, P, 2009. Social Work: The idea of a profession and the professional project. Locus Social 2(3), 19–35.

- Wildschut, A, Gamble, J & Mbatha, N, 2012. Understanding changing artisanal occupational milieus and identities: Conceptualising the study of artisans. Paper prepared for the Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP). June.

- Wildschut, A, Meyer, T & Akoojee, S, 2015. Changing artisanal identity and status: the unfolding South African story. HSRC Research Monograph, HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Wolff, K & Luckett, K, 2013. Integrating multidisciplinary engineering knowledge. Teaching in Higher Education 18(1), 78–92. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2012.694105