ABSTRACT

A high-level audit of administrative databases was conducted in more than 20 national government departments or entities. The aim was to investigate the relevance of datasets within these databases to skills planning by the government aimed at harmonising skills supply and demand in South Africa. The audit revealed that datasets have different levels of relevance and usability. There are datasets that: are relevant and immediately usable; are highly relevant and require some preparation; contain relevant variables but are currently undergoing validation and cleaning before they can be utilised; and are in an early stage of evolution. Based on these observations, the authors furthermore explore how databases can be understood from an evolutionary perspective. This investigation provides evidence that, in the field of skills planning, the government is progressing through the early phases of e-government systems development by cataloguing data resources and preparing for transactions between data users and providers.

1. Introduction

The South African government wants to substantively advance its skills planning capability to improve the match between work seekers’ skills and jobs available in the labour market. Reducing the imbalance between labour demand and supply can increase employment and reduce poverty. The Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) has launched an innovative project to develop and institutionalise a ‘credible mechanism for skills planning’ (DHET, Citation2009:8). Planning systems are built on data, the quality of which influences the validity and reliability of all planning processes and outcomes. To obtain the best quality data to populate the skills planning mechanism, the DHET needed to find out about databases relevant to skills planning owned by government departments. Government departments create many administrative databases and commission many survey studies, some of which contain useful information about skills supply and skills demand. There is no register of this type of database, therefore the DHET needed to establish whether any other government departments’ own databases contain data that are relevant to skills planning. The Human Sciences Research Council was commissioned to conduct a high-level audit of databases in the government’s possession that would be relevant to and useful for skills planning.

This study was thus aimed at establishing the existence and accessibility of databases relevant to skills planning. The study also provided an ideal opportunity to evaluate how government departments manage their databases, to consider how effectively databases are shared and used within the owner department, and to establish how often databases are shared with other departments and for what purpose. This relates to the level of maturity of e-government. The study reveals that government database holdings are for the most part unconnected and created in an ad-hoc manner. This article draws attention to the importance of putting in place protocols that guide government departments in the conduct of database development and management, and data sharing.

For the purpose of this study, a dataset is understood as a collection of data or data tables retrieved from a database. A data table may consist of a data matrix or columns and rows which represent variables and values. For analysis, the data will be manipulated using spreadsheet or statistical software. Each value in a data table is a ‘datum’ or a piece of data.

A database is understood as ‘an organised collection of data’ (Mehdi, Citation2006:162). It is controlled through a database management system designed to manage data, tables, stored procedures, permissions and access – in line with the purpose of the database.

2. Literature review

2.1. Information and databases

The increasing salience of data and information in policy development is openly acknowledged and reflected in phrases such as ‘evidence-based policy-making’. This means that government cannot afford to collect data, create databases and accumulate administrative data in an ad-hoc manner. Data resources must be properly managed and there are particular facets of this management. This article therefore speaks to the issue of managing databases so that their utility is maximised through being made more accessible, more shareable and more visible to potential users. These functions include accounting for legal requirements such as the Protection of Personal Information Act (KPMG, Citation2015).

As with the private sector, the public-sector organisations apply information and communication technologies (ICT) such as the Internet to extend both the reach and quality of service to clients. Just as crucial is the use of ICT to improve the efficiency of operations, to reduce costs, to add value to the data at their disposal, to obtain intelligence from the external environment for strategic management purposes and to maximise internal knowledge management and sharing processes.

The ability to share administrative data is essential in government. First, to coordinate activities so that government departments are cognisant of each other’s mandated activities and progress towards policy goals. This is especially vital where more than one department is delivering services in the same institutional domain (e.g. where the Department of Basic Education and the Department of Social Development are jointly involved in funding Early Childhood Development) or where many departments are jointly responsible for addressing complex social problems such as urbanisation or poverty.

Second, data sharing according to a regular process is necessary where the activities of several departments function in a chain of linked events (e.g. the Skills Levy involves transfers of information and funds from enterprises, to the South African Revenue Services [SARS], to the Treasury, to the Department of Higher Education, to the Sector Education and Training Authorities).

Third, departments must make information available to the public as part of practicing accountable governance, and devise ways of using ICT to provide interactive services to citizens (e.g. Filing tax returns online).

Fourth, data sharing must take place between government departments so that they can access relevant information that supports strategic decision-making and policy development. Supported by relevant ICTs and networks to transfer data and database environments to house data, sharing data is a core activity of e-government.

Prioritising database creation and usage, and supporting information technology (IT) systems will require fundamental changes in the institutional shape and behaviours of government. Toonen & Raadschelders (Citation1997:12) argue that ‘it should be recognised that IT not only influences government structures, but that equally, government structures affect the use of IT in the public sector … ’.

2.2. e-Government strategy

By developing its e-government capability the state seeks to enhance its information systems to improve policy-making, decision-taking, implementation and monitoring capabilities. This can assist in ensuring that all information resources at the government’s disposal can be most efficiently utilised (Pardo, Citation2000). Without access to a workable management information system, which consists of an optimal combination of technical (ICT) and human resources, managers in government departments are not able to make the best decisions in the public interest: ‘Timely availability of adequate, reliable, accurate and relevant data … have become a sine qua non not only of sound policy making but also of the measurement, monitoring and evaluation of public sector performance’ (Bertucci & Alberti, Citation2003:28).

For the purpose of this study the following World Bank (Citation2002) definition is used: ‘E–government refers to the use of information and communication technologies to improve the efficiency, effectiveness, transparency and accountability of government’. This implies intra-government relationships (United Nations, Citation2014:7) and requires improved horizontal integration of services and cooperation.

While e-government incorporates a range of functions and activities that involve using information technologies to generate, share, store and manipulate data (Lee, Citation2010), this article addresses the data side rather than the technology side. Government service delivery to citizens is a demographically large-scale and complex challenge. This article focuses on government databases that are the product of administrative or research processes. Depending on function, departments vary in the number and form of databases that they own.

The main issue under consideration is thus how government departments develop their database holdings and simultaneously enhance the level of e-government maturity to improve their ability to make better decisions.

It needs to be observed here that e-government is slower to innovate with systems development than private enterprises involved in e-commerce. There are a number of reasons for this, which includes the complexity of government structures at the different levels, uncoordinated approaches to e-government and the relatively high failure rate of e-government projects. In developing countries, systems may suffer from additional problems associated with manual and paper-driven systems with resultant poor quality and inefficiencies. Nevertheless, e-government as a paradigm stresses the opportunity – and more importantly the necessity – to transform government’s operational use of data to improve decision-making and, ultimately, service delivery (Fath-Allah et al., Citation2014).

Database systems development must be undertaken with the understanding that departments need to break down bureaucratic silos which could undermine cross-departmental e-government initiatives. A complementary view articulates the need to bring about ‘joined-up’ government (Harman & Brelade, Citation2001:1) at the levels of data exchange and policy coordination.

2.3. A model of e-government systems development and implications for databases

e-Government initiatives have frequently been described in the literature as ‘unmanageable’ (Layne & Lee, Citation2001:122), because there are many challenges, many competing approaches to meeting such challenges and the danger of attempting to achieve goals beyond their reach, while missing more appropriate intermediate steps in the process. Layne & Lee (Citation2001:123) have proposed a model which may prove useful in assisting public administrators to conceptualise the staged application of e-government in their departments. This model provides an outline of a series of ‘structural transformations of governments as they progress toward electronically enabled government’ involving mutually dependent processes of ICT enablement and modernising public administration. The model provides a platform to visualise how database development and data sharing can develop as part of overall systems development.

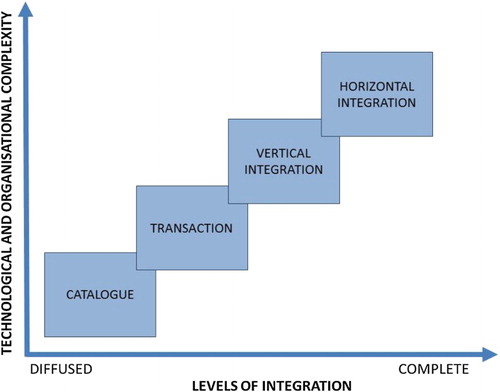

The model posits four stages of growth which imply increasing levels of complexity at the different levels of integration. The model is presented diagrammatically in .

Figure 1. Dimensions and stages of e-government development.

We can observe that ICT is applied in e-government in at least four ways:

the technical automation of tasks done previously by humans,

supporting increased participation of citizens,

the innovative development of new services and/or new mechanisms to offer such services and

the utilisation of accumulated administrative and research databases for intelligence gathering, analysis and strategic planning (Fang, Citation2002:2).

Achieving these goals will require increased integration of ICT systems across government departments both vertically and horizontally. The South African government is in the process of becoming ‘joined up’ and coordinated in meeting the various challenges of social development. This is likely to unfold according to the phases described in the model, which has implications for how databases might over time become increasingly accessible and interactive.

The stages in may be described as follows.

2.3.1. Catalogue

This is the first stage which involves initial efforts by the government that focus on the development of an online presence, cataloguing of disparate government electronic data holdings, the online presentation of government forms and provision for basic downloading of such documents.

2.3.2. Transaction

This stage allows citizens to interact with the government. It focuses on the connection of various internal government systems to an online interface supported by links to internal databases.

As transactions increase, in volume and in complexity (such as the creation of a one-stop shop access point), there will be a greater pressure to integrate systems, leading eventually to the citizen perceiving the government as an integrated information and transactional environment. There will be two main elements to this integration, namely vertical and horizontal integration.

2.3.3. Vertical integration

This will involve linking local-level systems to higher order systems in the government information infrastructure (e.g. from municipal, to provincial, to national). For example, a local driver’s license system could be linked to a national register of licensed taxi-drivers for cross-checking. The vertical integration of systems with similar functionality is expected to take place before integration of different functionalities. Vertical integration is likely to take place from the top down in many instances. Local government in developing countries is less likely to have the resources to implement e-government systems (Kaylor et al., Citation2001:293–307). In education and public health systems, vertical integration of data systems is more challenging from the bottom up, which requires database development capabilities at the school and clinic level.

2.3.4. Horizontal integration

This will involve the integration of services and information across different functions of government. For example, an enterprise should be able to pay its unemployment insurance to the Department of Labour, its taxes to the SARS and its Skills Levy to the Sector Education and Training Authority at the same time, because all of the systems either ‘talk’ to each other or work off the same database (Layne & Lee, Citation2001:124–6).

At one level, as already indicated, horizontal integration in e-government concerns the exchange of transactional data between an enterprise and different government entities. In another instance, data must be communicated between government agencies such as the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) and Employment Services South Africa so that unemployed work-seekers can be matched with employer vacancies. Data accumulating in administrative databases serve as evidence that certain transactions took place between participants. The same administrative data have high policy relevance because they can be used to assess the impact of government programmes. The key issue is to what extent government departments will share their own administrative data for policy and decision-making purposes.

Given that education is a multi-faceted phenomenon, it follows that a range of administrative databases in different departments bear relevance to the impact of education on school or university students. This means improved horizontal integration of data relevant to education across government departments would greatly improve the quality of education policy and decision-making.

This model is instructive because it shows how the opportunity for linking and sharing data increases as data systems develop over time. Furthermore, databases themselves can mature with time in terms of their quality and usability and become more valuable as sources of information that input into analysis and skills planning.

3. Purpose

The purpose of the study was to locate and investigate mainly administrative databases in government departments that contain data relevant to skills planning, and then to assess whether, according to given criteria, these databases or parts thereof (e.g. datasets containing particular variables) are of sufficient value to be linked to the DHET’s database system to use as part of the skills planning mechanism.

4. Methodology

As part of the process of data exploration, the Human Sciences Research Council commissioned a ‘South African Labour Market Microdata Scoping Study’ (Woolfrey, Citation2013). The wide coverage of this work conducted mainly through the World Wide Web provided an overview of the range of labour market and skill planning related data in various government departments, research and education institutions, and non-governmental organisations. The scoping study was limited, however, to the extent that it could not identify databases if they are not publically available online. This ‘audit’ study was therefore necessary to identify numerous internal government administrative databases that reside only within government systems and are not accessible in the public domain in any form.

The departments included in the study were nominated by the DHET. A uniform structure was followed for investigating and reporting on each departmental case study. Before interviewing, the team acquired information on the mandate, objectives, institutional structure, operational arrangements, administrative systems and data holdings of each department that would assist in identifying the relevant databases. Having this contextual understanding put the research team in the interview in a better position to ask appropriate follow-up questions about the various databases.

A semi-structured interview approach focused on the nature and function of databases containing data related to skills planning. The research team created two templates for capturing information on the databases: one for administrative data, and one for survey data. Each template was designed so that the key characteristics of the database and quality criteria could be captured. These included: data characteristics, data collection instrument(s), data management methods, data format, internal data users, and access conditions.

A full investigation into the quality of the data was not within the scope of this project. However, the research team relied on three sources of evidence regarding quality: firstly, the views of the departmental officials; and secondly, databases from which publications were produced and distributed that were considered to be of good quality. Thirdly, for the study purposes data quality was defined by Juran (Citation1999:998), ‘Data are of high quality … if they are fit for their intended uses in operations, decision making and planning’. For future exercises, data certified by the South African Statistical Quality Assessment Framework could be considered. The South African Statistical Quality Assessment Framework certified by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) is a very rigorous framework for the evaluation of data quality.

Once the case studies for each department or entity were written and a draft report generated, a draft for comments and verification was circulated to 47 people representing 17 government departments and entities who were interviewed during the study.

4.1. Departments included in this study

The investigation was not conducted within the DHET itself. Since its core mandate is education and skills development in the post-school sector, all of its own databases would be relevant. A number of government departments do have functions that impact on or relate to the employment status of citizens and non-citizens: the Department of Home Affairs processes births, deaths, emigration, immigration and work permits or visas; the Department of Labour administers the UIF and Public Employment Services; and the Department of Correctional Services manages the lives and studies of people who are not engaged in productive work of their choice. Additionally, statistical agencies of the state, primarily Stats SA, conduct official surveys to gather data on the functioning of households, businesses and on social challenges such as poverty and unemployment. Furthermore, several departments perform a post-school training function. For instance, the Departments of Health, Agriculture and Police Services are responsible for Colleges of Nursing, Agricultural Training Institutes and Police Academies, while the Departments of International Relations and Defence provide training for diplomatic and military operations.

Of critical importance was to establish whether the databases in the identified department contained specific variables relevant to skills planning. For example, databases of interest for skills planning would contain the details of individuals who interact with a government department in relation to their employment status or their educational status. If the UIF database contains information about the individual’s years of work experience, educational level, certificates and qualifications, occupation and annual salary, this is very useful for analysis when combined with biographical data (e.g. age, gender, race, place of residence, etc.). From these data elements it is possible to build up a profile of the population that registers for UIF, which in turn provides evidence of which occupations are shedding jobs and the demographic profile of those becoming unemployed. Such information provides intelligence which the government can use to devise interventions to counter the effects of unemployment.

Information captured on personal tax by taxpayers on e-government systems could, when linked to other comprehensive databases such as the National Learner Record Database of the South African Qualifications Authority, provide valuable labour market intelligence on issues such as the relationship between citizens’ occupations, education type and level, and wages. The SARS pointed out that it would in principle be possible to link qualification and skills data at the individual level to tax records where there is a common identifier, and thereby create a rich database for analysis and planning. However, because of the legal obligation to keep taxpayer information confidential, the SARS would have to undertake this matching and could only provide analysis at an aggregate level based on the integrated database.

Even though the focus was mainly on information emanating from the government’s administrative activities, researchers took note of other sources. Government departments routinely commission research or undertake their own research such as the ‘Job Opportunity Index’ conducted by the Department of Labour, or the ‘Register of Farmers’ at the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Stats SA, the national statistics authority, is a rich source of survey-based data and information relevant to skills planning. The following datasets are directly relevant to the activities of skills planning as envisaged by the client department, the DHET: the Quarterly Labour Force Survey, the Quarterly Employment Survey as well as the General Household Survey (Annual):

Stats SA as the National Statistical Coordinator is also mandated to promote coordination among producers of official and other statistics in order to advance quality, comparability and optimum use of official statistics and to avoid duplication by: formulating quality criteria and establishing standards, classifications and procedures; providing statistical advice; and promoting a public culture of measurement. (Stats SA, Citation2013:218)

The government is determined to ensure high standards of data quality that underlie confident decision-making.

5. Results of the audit

As an introduction to the audit, the framework of criteria established to guide the recommendation regarding datasets considered eligible for linking with the DHET database system are presented. The research team in collaboration with DHET officials negotiated the criteria framework. The main focus was on the type of data and the size (number of records) contained in the datasets. It should be noted that the criteria were set out as a guiding framework and that not all of the criteria were applicable in every instance.

The framework of criteria included the following:

Contains variable(s) related to skills planning (e.g. certificate, qualification, occupation, education level).

Existence of a linking variable: a common variable in each database that occurs at the unit record level (e.g. ID number).

Standard unit of collection and analysis: the area from which data were collected is based on a standard geographical unit of analysis/administration in South Africa (e.g. municipality, province).

Spatial reference: the geographical unit of analysis must be standard. Individuals or institutions can be allocated to this standard spatial unit of analysis. Enumerator area, postal code or unique geo-referenced coordinates are examples of such standard units.

Size: the database must cover an area on a standard unit of collection that is relevant or useful to skills planning (e.g. province versus an enumerator area).

Completeness: the proportion of the total population captured in the database.

Sampling: the sampling method should be acceptable.

Level of aggregation: data on a number of contiguous municipalities may be more useful than a dispersed group of municipalities unless they are purposively selected to address a particular question.

Primary data source: the database should be a complete administrative database or a complete survey dataset. This should include un-aggregated primary data and be based on the unit of collection (e.g. individual, household, school).

Data not in possession of the DHET: some departments acquire data (e.g. individuals’ university results) through interaction with citizens that duplicates DHET data. For example, Correctional Services possesses university study results of small numbers of offenders, which has only localised value to the individuals and the department for aggregated reporting.

The outcome of the audit revealed that current databases in seven government departments (), entities or programmes sufficiently fulfil the criteria set out. The members of this group reflect the strong concern of the DHET for bringing economic development data to the table with data from the post-school education and training system. It is evident also that the multi-billion rand Strategic Integrated Projects are viewed as important sources of demand. Other departments whose mandates impact on key government programmes are highlighted as owners of important datasets that require strengthening, such as Home Affairs which deals directly with skills migration, and Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries which is concerned to generate employment growth in agriculture and related value-added commodity markets while generating skills for safeguarding national food security and self-sufficiency.

Table 1: Departments or entities that sufficiently fulfilled the criteria as set

The audit revealed that databases have different levels of relevance and usability. There are databases that: are relevant and immediately usable; highly relevant and require some preparation; contain relevant variables but are currently undergoing validation and cleaning before they can be utilised; and are in an early stage of evolution.

6. Observations from the audit in relation to the theoretical literature regarding evolution of e-government and public-sector database systems

6.1. Stages of e-government development

This project in its own right is evidence of movement in government, driven by the need to obtain better data for decision-making. The project reflects the government’s decision to catalogue available data as the first step towards an integrated system, as reflected in Layne & Lee (Citation2001). It is notable that this is an initiative which emerges from a real information need perceived by the government in the field of skills planning and from the realisation that efforts to create better matching between labour market demand and supply are strategically important for the economic stability of the country after the Great Recession of 2007–9.

Further, this article reflects on how the departments with data holdings of relevance to skills planning should design, set up and implement the means of sharing data. A concerted programme in this direction would share the features of the phase of ‘transaction’ captured in Layne & Lee's (Citation2001) model.

6.2. Evolution of specific databases and of the data environment

An important starting point for this research was to acknowledge that within more than 20 national government departments at any given point in time there are likely to be new databases in creation as mandates change; as implementation methods are adapted and as budgets are reprioritised. This means that collectively the set of national government administrative databases is changing. Accordingly, the current study should not be seen as a one-off exercise and would bear repeating over a period of time.

Concretely, the research team’s observations made in the visits to departments highlighted how databases change over time, especially as they mature after initiation. Taking on board the concept of a database life-cycle alerted the team to the fact that among the databases canvassed some would contain data relevant to skills planning but might not be sufficiently developed to be immediately adopted for linking with the skills planning mechanism. Some time must be allowed for them to mature, to show consistent levels of quality and attract sufficient use to justify close analysis.

Alternatively, databases in different departments have been targeted for improvement by their host department and should begin to deliver viable data, for example:

The Employment Services South Africa public employment services database in the Department of Labour.

The Farmer’s Register in the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

The National Population Register in the Department of Home Affairs.

The DHET should take account of the changing nature of government database environments where databases may become more or less valued depending on changes in government priorities or as its mandate changes, or as administrative processes are redesigned.

The design and implementation of this audit provided a basic template and a methodology that can be adapted for possible follow-ups to be scheduled at some point in the future by the DHET. The necessity of conducting this kind of exercise at intervals will provide the DHET with the latest intelligence on which databases held by other government departments have matured sufficiently and are generating data of acceptable quality that qualifies them for inclusion in the skills planning mechanism.

6.3. Database ownership is related to the function of the department

It was quite apparent that there are differences between departments in how they view datasets, use datasets and acquire datasets in pursuing their own mandate. One dimension which became apparent is that departments without major administrative functions to perform tended to have very few datasets. In these cases, the practice was to request data that was needed from other departments. In one example, the Department of Performance Monitoring and Evaluation would request data from other departments according to which only specific data – sometimes just an indicator value – were shared. In another instance, the National Treasury created its Vulindlela database by integrating a number of databases including the Department of Public Service and Administration’s Personnel and Salary System data to create its own management information system. Consequently, neither of these departments possessed data that could be usefully incorporated into the skills planning mechanism.

6.4. Need to grow a culture of data caring and sharing

The Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP) is a substantial intergovernmental programme that is sure to lead to functional data exchange links over time with a number of departments. In this undertaking it is clearly going to be a path-breaker, bringing it into contact with a culture of poor data awareness in some departments that the research team had to contend with in its own tasks. Based on this experience, a few observations can be made that reflect challenges to be addressed in moving towards ‘joined-up government’ in terms of data sharing:

The culture of inter-department access and sharing of data does not seem particularly well developed.

Awareness among managers of datasets and databases as a vital asset for planning needs to be strengthened.

Staff members, other than those directly involved, have a limited picture of what data a department owns (other than human resource data since every employee must interact with human resource data systems by definition).

Difficulty experienced in identifying the ‘right’ people to speak to gives the impression that personnel have limited knowledge of what data other divisions have or use.

In the DHET and its allied institutions, data holdings are known and data exchange can be implemented with minimum problems. In other government departments, knowledge of databases relevant to skills planning is not complete, necessitating an exercise in database discovery for inclusion in the LMIP.

In doing so, the project will increase the volume of data relevant to skills planning in the LMIP which will enrich the data holdings of the LMIP and extend the scope of analysis.

Entry points with dedicated knowledgeable staff for accessing departments should be established. Most follow-up calls started with the switchboard: in a number of instances, contacts were initiated via the switchboard to try to track down the correct respondents.

Often the contact person given was not the most appropriate respondent: in many cases the ‘relevant’ contact person referred the request to another and again to another person before a meeting could be scheduled.

The success of these kinds of efforts will dictate the extent to which database and systems development moves towards higher levels of sophistication in terms of integration that is described by Layne & Lee (Citation2001).

6.5. Conclusion

The audit revealed a number of datasets of value to skills planning and analysis that are managed in government departments. The DHET has its own high-quality datasets containing comprehensive data on the supply of graduates from post-school institutions entering the labour market. Although datasets other than those in the DHET serve the mandate of the owner departments, some do contain data relevant to skills planning, but data relating to demand for skills is meagre. Few databases are currently of sufficient quality to be used, and a long-term approach to improving database sources needs to be pursued.

6.6. Recommendations

Closer functional relationships must be encouraged between government departments and Stats SA to embed the structures and functions of the National Statistics System to provide relevant, up-to-date and accurate data and information for planning purposes. It is recommended that effort must be made to encourage buy-in among government departments into the National Statistics System so that various standards for managing data systems can be recognised. This will contribute to a much improved environment for data sharing between departments.

Data-service units that are visible and accessible must be created by government departments to provide:

a publically visible point of contact that can assist and advise clients or users from other government departments, and

a visible point of contact that can assist and advise clients or users from inside the department who need data.

Where government department data are hosted by the State Information Technology Agency, it is recommended that the option of sourcing departmental data directly from Technology Agency should be exercised to ensure timeliness of delivery and accuracy of the databases being acquired. Information drawn off government databases must be obtained according to specified protocols, which can be time-consuming. Accordingly, it is recommended that where new data needs become known, these must be communicated in advance. Where required data are owned by one department, but managed and analysed in collaboration with Stats SA, it is recommended that a memorandum of understanding must include all partners clearly specifying roles and responsibilities.

7. Policy implications

The audit project focused on identifying and assessing datasets for inclusion in the skills planning mechanism. The inclusion of datasets for possible linking with the DHET data holdings need to be nuanced to take account of datasets that, at the stage of assessment, were not eligible for sharing but showed the potential to be linked with the LMIP environment once:

they matured and teething problems in the data were resolved;

buy-in and participation of the relevant population (e.g. unemployed persons registering on the Department of Labour’s Employment Services system) had stabilised; and

datasets were at a sufficiently high level to yield reasonably valid and reliable conclusions.

The DHET should engage with other government departments to meet its own data needs, but should do so as part of a national inter-government initiative to encourage better knowledge of and usage of government database resources. Specifically, the DHET should focus on database policies to improve its database holdings as follows:

Continue to map all available data in government and compare this with a schedule of needed databases, so that new database developments can be prioritised and scheduled.

Applying the concept of the database life-cycle, explore ways of improving current databases held by other departments with a view to using these data resources in the future.

Plan to support databases currently hosted in other departments which do not have the resources to sustain them to required quality standards. Awareness of data and databases as a vital asset for planning needs to be strengthened.

Collaborate within the National Statistics System to:

improve the visibility of data among policy makers and managers;

support functioning of research and database units based in departments;

ensure data personnel are familiar with cognate databases; and

initiate and support improved linking and sharing of data among departments.

Data sharing as a characteristic of e-government involves a wide range of activities both within and between government departments. As a result, plans and resources can become diffused in too many directions. Therefore, prioritisation of needs as well as determined focus is important for success.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bertucci, G & Alberti, A, 2003. Globalization and the role of the state: Challenges and Perspectives. In Rondinelli, DA & Cheema, DS (Eds.) , Reinventing government for the twenty-first century: State capability in a globalizing society. Kumarian Press, Bloomfield. pp. 24.

- DHET. 2009. Delivery agreement 1. For output 5.1 - Establish a credible institutional mechanism for skills planning. Department of Higher Education and Training. http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/DeliveryAgreement-Outcome5.pdf Accessed 16 April 2015.

- Fang, Z, 2002. E-Government in Digital Era: Concept, Practice, and Development. International Journal of The Computer, The Internet and Management 10(2), 1–22.

- Fath-Allah, A, Cheikhi, L, Al-Qutaish, RE & Idri, A, 2014. e-Government maturity models: A comparative study. International Journal of Software Engineering & Applications (IJSEA) 5(3), 71–91.

- Harman, C & Brelade, S, 2001. Knowledge, e-Government and the citizen knowledge. Management Review 4(3), 18–24.

- Juran, JM, 1999. Juran’s quality handbook. 5th edn. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. http://www.pqm-online.com/assets/files/lib/books/juran.pdf Accessed 20 October 2015.

- Kaylor, C, Deshazo, R & van Eck, D, 2001. Gauging e-Government: A report on implementing services among American cities. Government Information Quarterly 18(2), 293–307. doi: 10.1016/S0740-624X(01)00089-2

- KPMG, 2015. The protection of personal information act (POPI). http://www.kpmg.com/za/en/issuesandinsights/articlespublications/protection-of-personal-information-bill/pages/default.aspx Accessed 20 April 2015.

- Layne, K & Lee, J, 2001. Developing fully functional e-Government: A four stage model. Government Information Quarterly 18(2), 122–36. doi: 10.1016/S0740-624X(01)00066-1

- Lee, J, 2010. 10-year retrospect on stage models of e-Government: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Government Information Quarterly 27(3), 220–30. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2009.12.009

- Mehdi, K-P (Ed.), 2006. Dictionary of information science and technology, volume 1. Idea Group Inc (IGI), Hershey, p. 162.

- Pardo, TA, 2000. Realising the promise of digital government: It’s more than building a web site. Information Impacts October. http://www.netcaucus.org/books/egov2001/pdf/realizin.pdf Accessed 20 April 2015.

- Stats SA. 2013. Work programme 2013/14 / Statistics South Arica. Statistics South Africa. Pretoria.

- Toonen, TAJ & Raadschelders, JCN, 1997. Public sector reform in Western Europe, Paper presented at International Conference on Civil Service Systems in Comparative Perspective Indiana University, Indiana. April 5–7.

- United Nations, 2014. United Nations e-Government survey 2014: e-Government for the future we want. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, pp. 7.

- Woolfrey, L, 2013. South African labour market microdata scoping study. DataFirst, University of Cape Town. http://www.lmip.org.za/newsletter/item/south-african-labour-market-microdata-scoping-study Accessed 20 April 2015.

- World Bank, 2002. e-Government. http://www.worldbank.org/publicsector/egov/ Accessed 20 April 2015.