ABSTRACT

Given the rapid scale-up of antiretroviral treatment (ART), it is necessary to explore the impact of ART on labour force participation, employment and labour productivity. This article investigates labour market outcomes in a prospective cohort of public-sector ART clients in the Free State province of South Africa. Empirical results suggest that labour force participation increased markedly as the proportion of those too ill to work declined, becoming indistinguishable from participation rates in the general population. Unemployment rates, however, remain above those reported for the general population. ART and its health-related benefits therefore translate into increases in labour force participation, but not employment. Employment status at HIV diagnosis strongly predicts absorption in the labour force. Public-sector ART clients should be referred to vocational rehabilitation and occupational therapy programmes, and to welfare-to-work programmes, and the unskilled to adult education and training and further education and training programmes.

1. Introduction

The adverse microeconomic and macroeconomic impacts of the HIV and AIDS epidemic in South Africa and elsewhere is relatively well documented. Various household-level, firm-level and sector-level studies have shown how the epidemic stands to impact negatively on productivity, the size and composition of the workforce and the cost of doing business, translating into changes in demand and supply, and, in the case of small business, even resulting in business closures (Gaffeo, Citation2003; Fox et al., Citation2004; Liu et al., Citation2004; Rosen, Citation2004; Sendi et al., Citation2004; Bloom et al., Citation2007; Van Zyl & Lubisi, Citation2009; Abdulsalam, Citation2010; Abu et al., Citation2010; Oloo & Ojwang, Citation2010; Okezie et al., Citation2011). These supply-side and demand-side effects in turn filter through the macroeconomy to impact negatively on estimates of aggregate economic output, economic growth, unemployment and the income distribution (Cuddington, Citation1993; Cuddington & Hancock, Citation1995; Arndt & Lewis, Citation2000; Bonnel, Citation2000; Nicholls et al., Citation2000; Dixon et al., Citation2001; Ellis et al., Citation2003; Nattrass, Citation2003; Haacker, Citation2004; Burger & De Villiers, Citation2005; Corrigan et al., Citation2005; McDonald & Roberts, Citation2006).

With the rapid scale-up in the provision of subsidised or free antiretroviral treatment (ART) in developing countries such as South Africa, and its resultant short-term and sustained medium to long-term health-related and clinical benefits – which are well documented (Beard et al., Citation2009; El-Sadr et al., Citation2012) both in South Africa in general (Coetzee et al., Citation2004; Jelsma et al., Citation2005; Louwagie et al., Citation2007; Boulle et al., Citation2008, Citation2010) and in the Free State province in particular (Booysen et al., Citation2007; Fairall et al., Citation2008; Wouters et al., Citation2009) – the focus in research on the economics of HIV and AIDS has shifted towards determining how the expansion of ART may ameliorate these adverse microeconomic and macroeconomic consequences of HIV and AIDS (Charalambous et al., Citation2007; Jefferis et al., Citation2008; Rosen et al., Citation2008; Ventelou et al., Citation2008; Fultz & Francis, Citation2011). Modelling, moreover, confirms that scaled-up and universal antiretroviral (ARV) treatment is beneficial economically (Resch et al., Citation2011; Ventelou et al., Citation2012).

An important area of enquiry in this field is studies on the productivity, labour force participation and employment-related benefits of ART, which represents ‘a critical [economic,] social and health issue facing people living with HIV/AIDS’ (Worthington et al., Citation2012:231; labour force participants include the employed and searching unemployed, see footnote 4 for more detail). Empirical evidence in this area is mixed, with some earlier studies reporting that successful ARV treatment translates into return to work and increased productivity (Bernell & Shinogle, Citation2005; Lem et al., Citation2005; Razzano et al., Citation2006; Larson et al., Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2013; Morineau et al., Citation2009; Habyarimana et al., Citation2010; Rosen et al., Citation2010), while other studies record improvements in labour participation or only ability to work, but not necessarily in employment (Ajithkumar et al., Citation2007; Coetzee Citation2007, Thirumurthy et al., Citation2008; Wagner et al., Citation2009). Another body of work investigated interventions in vocational counselling and occupational therapy that may enhance the work experiences of people living with HIV/AIDS (Salz, Citation2001; Berry & Hunt, Citation2005; Conyers, Citation2005; Escovitz & Donegan, Citation2005; Goldblum & Kohlenberg, Citation2005; Martin et al., Citation2005; McGinn et al., Citation2005; Bowyer et al., Citation2006; Braveman et al., Citation2006; Egan & Hoagland, Citation2006; Martin et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b).

This article investigates labour market behaviour in the era of ART using data from a cohort study of patients enrolled in the Free State province’s public-sector ART programme during the initial phases of the ARV roll-out. More specifically, the article aims to explore five specific research factors: firstly, the article aims to document the health-related and clinical benefits of ART that are likely to facilitate changes in labour market behaviour among study participants. Secondly, the article documents changes in labour market outcomes across the ARV treatment career. In the third instance, the article compares the former trends with trends in corresponding labour market outcomes reported in national labour force statistics. Finally, the article determines the extent to which ART and its associated health-related and clinical benefits and employment status at HIV diagnosis represent important predictors of key labour market outcomes.

2. Data

The Ethics committee of the Faculty of Humanities University of the Free State approved the study protocol. Study participants were sampled randomly from a list of patients who were eligible to commence ART during the first two months of the programme.Footnote1 In each of the five health districts, 80 patients were sampled randomly from these lists proportional to the numbers at each health care facility who had commenced treatment or were waiting to initiate treatment.Footnote2 As such, the study includes patients who had not yet initiated ARV treatment as well as patients on ART. Trained enumerators conducted structured, face-to-face baseline interviews with ART patients. Written, informed consent was obtained from study participants by the nursing personnel at the respective clinics, as well as by the enumerator.

Where cohort patients were lost to follow-up in subsequent survey rounds, replacements were sampled randomly from the original sampling frame. Enumerators obtained written, informed consent from study participants prior to each follow-up interview. Five rounds of follow-up interviews were conducted with patients at intervals of approximately six to nine months during the period January 2005–December 2008, although the actual timing between interviews does vary somewhat due to logistical and practical constraints ().

Table 1. Number of patient interviews, by survey round.

In total, 1844 interviews were conducted with 452 individual patients who were eligible for and ready to commence ART. By the fifth follow-up, as per the note to , 169 patients had been lost, primarily due to mortality among study participants as well as refusal (). This translates into an aggregate attrition rate of 41.8%. A total of 83 study participants were recruited from the original sampling frame to replace subjects lost to attrition. In the subsequent pages, these data are employed to investigate the role of socio-demographics and ART dynamics in explaining observed labour market outcomes. First, an investigation is made into the possible existence of selection and attrition bias with regards to key socio-demographic characteristics, health status and the main study outcomes.

Table 2. Reasons for loss to follow-up.

The replacements do not differ significantly from the respondents interviewed at baseline in terms of sex, education and marital status (). The exception, however, is age. As expected, because of the cohort design of the study, replacements on average were interviewed at a higher age compared with respondents interviewed earlier, at baseline. As one would expect, replacements, who by that time would have been on treatment longer and hence are likely to have responded to treatment and be healthier, do report better health status. The differences are not statistically significant at the 5% level, however, and neither are the differences in employment status – although one does, as expected, see higher levels of employment and lower levels of illness, respectively. There is therefore no clear evidence of selection bias in the study.

Table 3. Socio-demographic characteristics of baseline respondents and replacements.

There likewise is no evidence of attrition bias in the main socio-demographic characteristics and labour market status. As expected, health status is considerably and significantly poorer among subjects lost to follow-up, as implied by mortality being the most important reason for loss to follow-up (). Where these subjects had remained in the study, one could possibly expect continued poor health and hence poorer labour market outcomes, which implies that the improvements in labour market outcomes reported in this study may be overstated.

Table 4. Attrition analysis.

3. Method

In the bivariate analysis in Sections 4 and 5 of the article, t tests, chi-square tests and one-way analyses of variance were employed to determine whether trends in treatment outcomes and labour market outcomes differ statistically significantly across treatment duration. The specification of the multivariate regression models reported in Section 6 was informed by conceptual frameworks and overviews published in the relevant literature (Ferrier & Lavis, Citation2003; Hergenrather et al., Citation2004; Maguire et al., Citation2008; Worthington et al., Citation2012). Various proxies of treatment and treatment benefits and independent, explanatory variables representing key socio-demographic characteristics and other controls were regressed on labour market outcomes. The following model was estimated using panel fixed effects (FE) logistic regressions:where:

is a vector of (binary) labour market status variables: too ill to work (1 = yes), labour force participation (1 = yes) and employment/absorption (1 = yes).

xit is a vector of socio-economic and other control variables: age, age squared, sex, race, education, type of dwelling, marital status, household size, household dependency ratio, disability grant status, number of employed household members (excluding the patient), need for secrecy about HIV status and district.

ARV_Treatmentit is a vector of ARV treatment/health status variables: being on treatment (treatment status, 1 = yes/on treatment), treatment duration (categorical: pre-ART, 0 to 3 months, 3 to 12 months, 12 to 24 months, 24 to 36 months, >36 months), treatment duration (number of months on treatment) and employment status at HIV diagnosis (1 = employed). Furthermore, treatment status was interacted with self-reported health-related quality of life (EQ-VAS and EQ-5D) and measures of immunologic (CD4 mm3) and virologic (RNA ml) response to ART.

is the logistic cumulative distribution function (cdf), with ez/1−e2 (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2005:795), while

and γ are vectors of model parameters, and αi are individual FE.

The FE model represents an appropriate econometric strategy for assessing the causal effect of the ARV_Treatment variables on the dependent variables (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2009:223), as it addresses endogeneity driven by the correlation between treatment and time-invariant unobservables and allows for the consistent estimation of the marginal effects of these explanatory variables on the labour market outcome variables (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2009:237).Footnote3 Labour market outcomes, the dependent variables, were defined in line with the South African Labour Force Survey (LFS), based on responses to a set of survey questions.Footnote4 The Hausman specification test is employed to determine whether the null hypothesis that the random effects regression model is appropriate can be rejected in favour of the FE regression model (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2009:266–7). In both cases the FE model will yield consistent estimates; if the null hypothesis is not rejected, however, the random effects estimator would be more efficient.

4. Antiretroviral treatment and health outcomes

ART most probably impacts on labour market outcomes via its impact on ARV patients’ health status. presents the significant improvements over time in study participants’ health status with respect to the two key bio-medical markers of treatment response, namely CD4 and viral load, which are used to measure immunologic and virologic responses to treatment, respectively.

Table 5 Subjective health status and clinical outcomes, by treatment duration.

A similar trend is observed in more subjective, self-reported measures of health status. shows all such outcomes to have improved significantly across the treatment career for ART clients observed in each survey round. The question, however, is to what extent these observed improvements in health status have translated into changes in labour market behaviour among patients on ART.

5. Labour market outcomes across the ARV treatment career

In the subsequent pages, four main labour market outcomes (i.e. being too ill to work, labour force participation, unemployment and labour force absorption) are compared across treatment duration. First, however, labour force status is compared across treatment duration ().

Table 6. Labour force status, by treatment duration.

There is a statistically significant difference in labour force status across treatment duration (p < 0.001). Prior to treatment initiation, almost half of the study participants reportedly were too ill to work. This percentage was even higher at first HIV diagnosis, where two in three respondents indicated that they were too ill to work, which reflects the general trend that patients only present for testing when relatively ill (Schwarcz et al., Citation2011; Dickson et al., Citation2012; Dowson et al., Citation2012; Jürgenson et al., Citation2012). This percentage declined markedly and consistently to one in five respondents as treatment duration increased. Concurrently, the proportion of employed study participants declined between HIV diagnosis and the early part of ART initiation but increased thereafter, rising to one in four study participants at ≥2 years of ARV treatment, which is well below the approximate 50% reported in studies in developed countries (Worthington et al., Citation2012). Dray-Spira et al. (Citation2006) likewise found employment losses to be relatively common in the earlier, pre-ART stages of HIV disease. The proportion of unemployed and discouraged respondents remained relatively high, however, and even increased over the ARV treatment career, as individuals too ill to work joined the labour force, but did not find employment. In the subsequent sections, trends in individual labour market outcomes are assessed relative to calendar time, which allows a comparison with corresponding labour market trends observed in the general population.

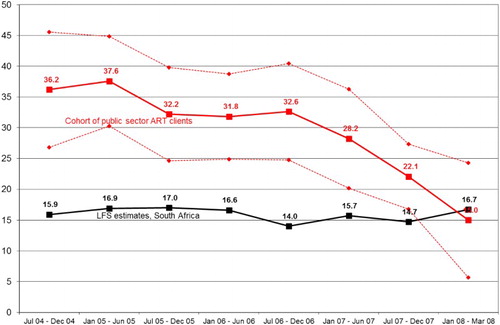

5.1. Being too ill to work

illustrates how the proportion of study participants too ill to work declined over time and by early 2008, although still somewhat higher, was not significantly different from the proportion of the working-age population in South Africa who are disabled or too ill to work.

Figure 1. Trends in illness/disability among the workforce (%).

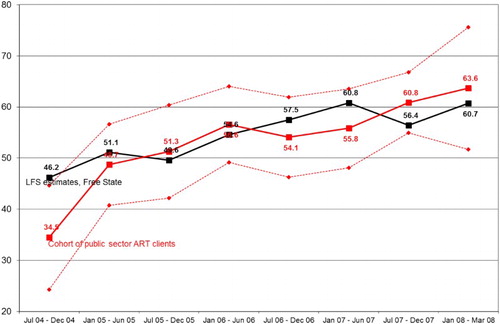

5.2. Labour force participation

Early in the treatment career, in 2004, the labour force participation rate among ARV patients was significantly below the estimates from the LFS. Subsequently, however, labour force participation rates among public-sector ART clients remain indistinguishable from participation rates observed among the general population, tracking the general upward trend reported over the period ().

Figure 2. Trends in labour force participation rates (%).

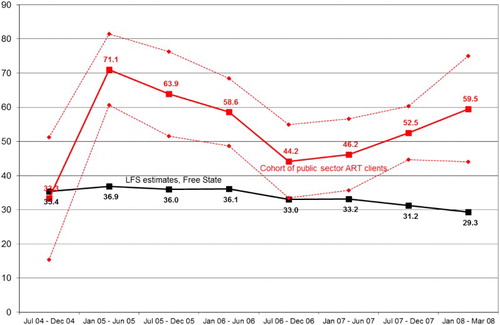

5.3. Unemployment

The (narrow) unemployment rate, although increasing in the early treatment career and having declined statistically significantly by mid 2006 to end 2007, in the longer term increased to levels observed early in the ARV treatment career (). As expected, given the fact that public-sector ART clients are likely to represent relatively poor, uneducated individuals (refer to ), the unemployment rate among study participants, with the exception of the first period under treatment, remains significantly higher throughout than among the general population.

Figure 3. Trends in unemployment rates (%).

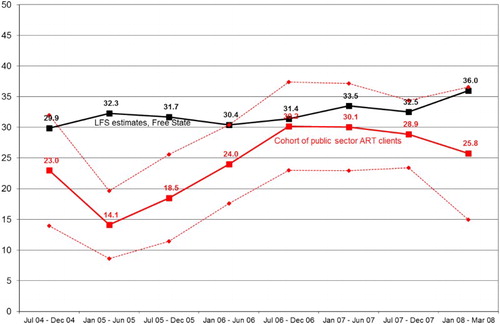

5.4. Labour force absorption

The labour force absorption rate among study participants exhibits a sluggish but upward trend. The absorption rate among public-sector ART clients had significantly increased by 2006/07, well beyond rates observed early in the ARV treatment career. Only in 2005, however, did the rate exceed the provincial rate. Beyond 2005, the absorption rate is indistinguishable from the provincial rate (). The difference between the study cohort and the general population therefore persists only for the unemployment rate, with patients facing higher unemployment rates throughout their treatment career.

Figure 4. Trends in labour force absorption rates (%).

6. ARV treatment as a predictor of labour market outcomes

Labour force participation increases markedly as the proportion of public-sector ART clients who are too ill to work declines. Participation for many does not translate into employment. Despite absorption rates being equivalent in the two populations, higher unemployment rates remain endemic. The question addressed in the subsequent regression analysis, moreover, is how treatment status and duration as well as the health-related and clinical benefits of ART may independently predict observed labour market outcomes.Footnote5

Receiving ARV treatment and being on ART for longer than one year is associated with statistically significantly smaller odds of being too ill to work and with statistically significantly larger odds of labour force participation (). Treatment duration in months is not significantly associated with either being too ill to work, participating in the labour force or being absorbed in the labour force.

Table 7. ARV treatment as predictors of labour market outcomes in public-sector ART clients.

The improved health-related quality of life for those on ARV treatment, however, translates into statistically significantly lower odds of being too ill to work and statistically significantly larger odds of not only participating in the labour force but also being absorbed into the labour force (). Among the clinical outcomes, only immunologic response predicts labour market outcomes, more specifically being too ill to work and participating in the labour force. Apart from self-reported health status, the health-related benefits of ARV treatment do not translate into improved odds of being absorbed into the labour force.

Table 8. Health status and clinical outcomes as predictors of labour market outcomes in public-sector ART clients.

Table 9. Employment status at HIV-positive diagnosis as predictor of labour market outcomes in public-sector ART clients.

The impact on labour market outcomes of employment status at HIV diagnosis is significantly larger in magnitude compared with the impact of treatment duration and health-related benefits. Being employed at HIV diagnosis increased the odds of labour force participation more than two-fold and the odds of absorption in the labour force almost 10-fold. Thus, respondents not employed when first having learnt their HIV-positive status, other things being equal, are likely to remain locked out of the labour market ().

7. Limitations

The presented findings, their interpretation and the following resultant conclusions should be interpreted with caution due to various methodological and econometric limitations. This study focuses mainly on paid employment and therefore underestimates the potential labour-related benefits of ARV treatment with respect to unpaid unemployment, particularly production within the household. Clinical markers (recorded at facility visits) and labour market outcomes (reported at interview dates) were observed at different points in time. As a result, it is methodologically impossible to determine the extent to which clinical treatment response predicts labour market outcomes.

In addition, true counterfactuals of labour market outcomes remain unknown due to the absence of corresponding data from comparative samples of known HIV-negative persons and known HIV-positive persons not on ART, which requires a case–control study design. The said comparisons with estimates from the LFS are used as an indicative yardstick rather than as a counter-factual.

Attrition bias is present in the study, but the bias could not be corrected for due to econometric considerations. A set of attrition probit regressions was estimated using the variables in as predictors of study attrition. In all three regressions, the coefficients on the health variables were found to consistently differ significantly from zero. As expected, being in poorer health was positively associated with attrition in all three probit attrition regressions. However, the overall fit of all three attrition probit regressions were poor: the overall Wald chi-square statistic was only statistically significantly different from zero at the 5% level for the attrition probits in which EQ-VAS and EQ-5D were the health indicators, while the pseudo R2 value for the three probit regressions ranged between 5.3 and 6.9%. Using these attrition probits to construct inverse probability weights to address attrition bias is inappropriate insofar as the low predictive power of these attrition models (as evidenced by poor overall model fit statistics) leads to the violation of the ignorability assumption, which is crucial for identification (Kerr & Teal, Citation2015). Importantly, moreover, the main study outcome – employment status – does not differ statistically significantly by attrition.

Labour market outcomes, moreover, were observed at one point in time only – namely at the interview date – with no information being collected on the timing and duration of these events. As a result, there are limitations in using these data to fully explore the dynamics of labour market behaviour among study participants. Presnell (Citation2006) and Worthington et al. (Citation2012) emphasise that quantitative analysis such as that presented here only reflects part of the larger narrative of how HIV-positive individuals fair in the labour market. Further qualitative research is therefore required to present a full picture of labour market behaviour and related issues as experienced by people living with HIV/AIDS.

8. Conclusion

Results from descriptive analyses show that both clinical and subjective markers of health status have improved markedly with treatment duration. These analyses also show that labour force participation increased markedly as the proportion of public-sector ART clients that are too ill to work declined, becoming indistinguishable from participation rates in the general population. Labour force participation for most study participants, however, did not translate into employment, with unemployment rates remaining relatively high, markedly above rates reported for the general population. Treatment and its health-related benefits predominantly translate into increases in labour force participation. Sustainable, effective ARV treatment therefore has the positive spin-off of growing the country’s army of potential workers. For this reason, it remains important to further scale-up access to ART by addressing existing barriers to uptake of HIV testing (Deblonde et al., Citation2010) through tailor-made interventions aimed at specific populations (Creel & Rimal, Citation2011), not only to maximise the prevention benefits of ART (Granich et al., Citation2010), but to fully exploit the wider direct and indirect economic benefits of ARV treatment.

The more recent literature documents evidence in support of the positive impact of ARV treatment, not only on labour force participation (Thirumurthy & Zivin, Citation2012; Venkataramani et al., Citation2014), as we found here, but on employment status, both in the short and longer term (El-Sadr et al., Citation2012). In a Ugandan study, the likelihood of working was found to have increased at six and 12 months on treatment (Linnemayr et al., Citation2013). In India, rapid and sustained improvements in employment status had been achieved two years following ART initiation (Thirumurthy et al., Citation2013). In South Africa, Bor et al. (Citation2012) found that employment levels by the fourth year of treatment had recovered to 90% of levels observed three to five years prior to treatment initiation. Rosen et al. (Citation2014) moreover report improvements in employment outcomes through years three to five of an ARV treatment programme in South Africa. Employment status has also been found to be positively correlated with CD4 counts in a study from Uganda (Thirumurthy et al. Citation2013).

There are various reasons as to why in this study we do not observe corresponding improvements in employment prospects. Subjects in this population are likely to be uneducated and potentially unemployable, partly as a result of the pro-poor rationing of ARV treatment during the early phases of the roll-out of treatment in South Africa. HIV-positive people also face discrimination in the labour market and therefore could find it difficult to find employment. The studies, moreover, are not directly comparable insofar as the cohorts are from different countries and settings and from a range of different treatment programmes, each with its peculiar characteristics.

In order to inform policy recommendations, further research is required to better understand why public-sector ART clients are unemployed. Potential policy recommendations include the following: insofar as ARV treatment in this study does not guarantee employment per se, but rather prior employment status – in this case, more specifically, being employed when first testing HIV-positive – ARV clients should be referred to vocational rehabilitation and occupational therapy programmes aimed at facilitating return to work. For unskilled, unemployable individuals, who are likely to make up a large share of public-sector ART clients, referral to and enrolment in adult education and training and in further education and training programmes could be beneficial. In the absence, moreover, of employment opportunities for public-sector ART clients and income support for unemployed adults, the disability grant is likely to remain an important safety net for most patients and their households. The risk of patients adhering sub-optimally to treatment to retain their social welfare grants and of patients becoming dependent on social assistance, however, remains real and calls for (referrals to) an integrated welfare-to-work programme in the public sector, to maximise the sustained economic benefits of ARV treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants and the fieldwork staff as well as the Free State Department of Health and the National Health Laboratory Service.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The public-sector ART programme did not commence simultaneously in all five health districts. The original sampling frame excluded patients eligible for ART (i.e. CD4 ≤ 200 and/or WHO AIDS stage 4) but who were not certified as ready to commence with treatment by a physician, in many cases due to patients having to first complete their tuberculosis treatment. The results thus cannot be generalised to all patients eligible for ART, but rather to public-sector patients ready to commence ART.

2 In Xhariep district, the list included less than 80 patients: as a result, all treatment and non-treatment cases were included in the study.

3 Theoretically, the data also allow an investigation of predictors of labour market transitions, such as becoming a labour force participant, gaining employment or being newly absorbed in the labour force. Unfortunately, the numbers of transitions in the dataset are relatively small, which substantially reduces the statistical power of the ensuing FE multivariate regression analyses, given the ‘expensive [nature of FE] in terms of degrees of freedom’ (Gujarati, Citation2003:647) as a result of losing those observations where yit =0 for all t or yit =1 for all t (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2009:614).

4 The labour market indicators and definitions used in the LFS comparisons correspond to those used by Statistics South Africa in its LFSs and Quarterly Labour Force Surveys. Unemployment refers to all individuals aged 15 to 64 years who were not employed in the seven days preceding their interviews; who were willing and able to work during this time, while having taken active steps to find employment in the four weeks prior to the interview. Labour force participants are either employed or unemployed, while the labour force participation rate is obtained by dividing the number of labour force participants by number of people aged 15 to 64 years. The labour force absorption rate is obtained by dividing the number of employed individuals by the number of individuals aged 15 to 64 years.

5 Admittedly, the general economic upswing experienced in South Africa during 2006/07 may play an important part in explaining the observed trends in labour market outcomes during this period. However, it is not possible to determine its role in explaining these trends in the absence of comparable data for a representative panel of economically active individuals in the Free State province.

References

- Abdulsalam, S, 2010. Macroeconomic effects of HIV/AIDS prevalence and policy in Nigeria: A simulation analysis. Forum for Health Economics and Policy 13(2), 8.

- Abu, GA, Ekpebu, ID & Okpachu, SA, 2010. The impact of HIV/AIDS on agricultural productivity in Ukum local government area of Benue State, Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology 31(3), 157–163.

- Ajithkumar, K, Iype, T, Arun, KJ, Ajitha, BK, Aveenlal, KPR & Antony, TP, 2007. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on vocational rehabilitation. AIDS Care 19(10), 1310–1312.

- Angrist, JD & Pischke, J-S, 2009. Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Arndt, C & Lewis, JD, 2000. The macro implications of HIV/AIDS in South Africa: A preliminary assessment. South African Journal of Economics 68(5), 380–392.

- Beard, J, Feeley, F & Rosen, S, 2009. Economic and quality of life outcomes of antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in developing countries: A systematic literature review. AIDS Care 21(11), 1343–1356.

- Bernell, SL & Shinogle, JA, 2005. The relationship between HAART use and employment for HIV-positive individuals: An empirical analysis and policy outlook. Health Policy 71, 255–264.

- Berry, JD & Hunt, B, 2005. HIV/AIDS 101: A primer for vocational rehabilitation counselors. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 22, 75–83.

- Bloom, DE, Bloom, LR, De Lay, P, Paua, F, Samans, R & Weston, M, 2007. World Economics 8(4), 125–141.

- Bonnel, R, 2000. HIV/AIDS and economic growth: A global perspective. South African Journal of Economics 68(5), 360–379.

- Booysen, FLR, Van Rensburg, HCJ, Bachmann, M, Louwagie, G & Fairall, L, 2007. The heart in HAART: Quality of life of patients enrolled in the public sector antiretroviral treatment programme in the Free State province of South Africa. Social Indicators Research 81(2), 28–329.

- Bor, J, Tanser, F, Newell, M & Bärnighausen, T, 2012. In a study of a population cohort in South Africa, HIV patients on antiretrovirals had nearly full recovery of employment. Health Affairs 31(7), 1459–1469.

- Boulle, A, Bock, P, Osler, M, Cohen, K, Channing, L, Hilderbrand, K, Mothibi, E, Zweigenthal, V, Slingers, N, Cloete, K & Abdullah, F, 2008. Antiretroviral therapy and early mortality in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86(9), 678–687.

- Boulle, A, Van Cutsem, G, Hilderbrand, K, Cragg, C, Abrahams, M, Mathee, S, Ford, N, Knight, L, Osler, M, Myers, J, Goemaere, E, Coetzee, D & Maartens, G, 2010. Seven-year experience of a primary care antiretroviral treatment programme in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS 24(4), 563–72.

- Bowyer, P, Kielhofner, G & Braveman, B, 2006. Interdisciplinary staff perceptions of an occupational therapy return to work program for people living with AIDS. Work 27, 287–294.

- Braveman, B, Levin, M, Kielhofner, G & Finlayson, M, 2006. HIV/AIDS and return to work: A literature review one-decade post-introduction of combination therapy (HAART). Work 27, 295–303.

- Burger, R & De Villiers, P, 2005. The macroeconomic impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa: A supply-side analysis. Journal of Studies in Economics and Econometrics 29(1), 1–14.

- Cameron, AC & Trivedi, PK, 2005. Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Cameron, AC & Trivedi, PK, 2009. Microeconometrics using Stata. Stata Press, College Station, TX.

- Charalambous, S, Grant, AD, Day, JH, Pemba, L, Chaisson, RE, Kruger, P, Martin, D, Wood, R, Brink, B & Churchyard, GJ, 2007. Establishing a workplace antiretroviral therapy programme in South Africa. AIDS Care 19(1), 34–41.

- Coetzee, C, 2007. The impact of highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) on employment in Khayelitsha. South African Journal of Economics 76(S1), S75–S85.

- Coetzee, D, Hildebrand, K, Boulle, A, Maartens, G, Louis, F, Labatala, V, Reuter, H, Ntwana, N & Goemaere, E, 2004. Outcomes after two years of providing antiretroviral treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS 18(6), 887–95.

- Conyers, LM, 2005. HIV/AIDS as an emergent disability: The response of vocational rehabilitation. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 22, 67–73.

- Corrigan, P, Glomm, G & Mendez, F, 2005. Aids crisis and growth. Journal of Development Economics 77(1), 107–124.

- Creel, AH & Rimal, RN, 2011. Factors related to HIV-testing behaviour and interest in testing in Namibia. AIDS Care 23(7), 901–907.

- Cuddington, JT, 1993. Modeling the macroeconomic effects of HIV/AIDS, with an application to Tanzania. World Bank Economic Review 7(2), 173–189.

- Cuddington, JT & Hancock, JD, 1995. The macroeconomic impact of AIDS in Malawi: A dualistic, labour surplus economy. Journal of African Economies 4(1), 1–28.

- Deblonde, J, De Koker, P, Hamers, FF, Fontaine, J, Luchters, S & Temmerman, M, 2010. Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health 20(4), 422–432.

- Dickson, NP, McAllister, S, Sharples, K & Paul, C, 2012. Late presentation of HIV infection among adults in New Zealand: 2005–2010. HIV Medicine 13(3), 182–189.

- Dixon, S, McDonald, S & Roberts, J, 2001. Aids and economic growth in Africa: A panel data analysis. Journal of International Development 13(4), 411–426.

- Dowson, L, Kober, C, Perry, N, Fisher, M & Richardson, D, 2012. Why some MSM present late for HIV testing: A qualitative analysis. AIDS Care 24(2), 204–209.

- Dray-Spira, R, Persoz, A, Boufassa, F, Gueguen, A, Lert, F, Allegre, T, Goujard, C, Meyer, L & The Primo Cohort Study Group, 2006. Employment loss following HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapies. European Journal of Public Health 16(1), 89–95.

- Egan, BE & Hoagland, J, 2006. In-house work opportunities: Implications for housing organizations serving persons living with HIV/AIDS. Work 27, 247–253.

- Ellis, L, Smit, B & Laubscher, P, 2003. The macro-economic impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Journal for Studies in Economics and Econometrics 27(2), 1–28.

- El-Sadr, WM, Holmes, CB, Mugyenyi, P, Thirumurthy, H, Ellerbrock, T, Ferris, R, Sanne, I, Asiimwe, A, Hirnschall, G, Nkambule, RN, Stabinski, L, Affrunti, M, Teasdale, C, Zulu, I & Whiteside, A, 2012. Scale-up of HIV treatment through PEPFAR: A historic public health achievement. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 60(Suppl 3), S96–S104.

- Escovitz, K & Donegan, K, 2005. Providing effective employment supports for persons living with HIV: The KEEP project. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 22, 105–114.

- Fairall, LR, Bachmann, MO, Louwagie, GMC, Van Vuuren, C, Chikobvu, P, Steyn, D, Staniland, GH, Timmerman, V, Msimanga, M, Seebregts, CJ, Boulle, A, Nhiwatiwa, R, Bateman, ED, Zwarenstein, MF & Chapman, RD, 2008. Effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in a South African program: A cohort study. Archives of Internal Medicine 168(1), 86–93.

- Ferrier, S & Lavis, J, 2003. With health comes work? People living with HIV/AIDS consider returning to work. AIDS Care 15(3), 423–435.

- Fox, MP, Rosen, S, MacLeod, WB, Wasunna, M, Bii, M, Foglia, G & Simon, JL, 2004. The impact of HIV/AIDS on labour productivity in Kenya. Tropical Medicine and International Health 9(3), 318–324.

- Fultz, E & Francis, JM, 2011. Employer-sponsored programmes for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS: Recent experience from sub-Saharan Africa. International Social Security Review 64(3), 1–19.

- Gaffeo, E, 2003. The economics of HIV/AIDS: A survey. Development Policy Review 21(1), 27–49.

- Goldblum, P & Kohlenberg, B, 2005. Vocational counselling for people with HIV: The client-focused considering work model. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 22, 115–124.

- Granich, R, Crowley, S, Vitoria, M, Lo, Y-R, Souteyrand, Y, Dye, C, Gilks, C, Guerma, T, De Cock, KM & Williams, B, 2010. Highly active antiretroviral treatment for the prevention of HIV transmission. Journal of the International AIDS Society 13(1), 1–8.

- Gujarati, DN, 2003. Basic econometrics. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Haacker, M, 2004. The macroeconomics of HIV/AIDS. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

- Habyarimana, J, Mbakile, B & Pop-Eleches, C, 2010. The impact of HIV/AIDS and ARV treatment on worker absenteeism: Implications for African firms. Journal of Human Resouces 45(4), 809–839.

- Hergenrather, KC, Rhodes, SD & Clark, G, 2004. Employment-seeking behavior of persons with HIV/AIDS: A theory-based approach. Journal of Rehabilitation 70(4), 22–32.

- Jefferis, K, Kinghorn, A, Siphambe, H & Thurlow, J, 2008. Macroeconomic and household-level impacts of HIV/AIDS in Botswana. AIDS 22(S1), S113–S119.

- Jelsma, J, MacLean, E, Hughes, J, Tinise, X & Darder, M, 2005. An investigation into the health-related quality of life of individuals living with HIV who are receiving HAART. AIDS Care 17(5), 579–588.

- Jürgenson, M, Tuba, M, Fylkesnes, K & Blystad, A, 2012. The burden of knowing: Balancing benefits and barriers in HIV testing decisions. A qualitative study from Zambia. BMC Health Services Research 12, 2.

- Kerr, A & Teal, F, 2015. The determinants of earnings inequalities: Panel data evidence from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of African Economies 24(4), 530–558.

- Larson, BA, Fox, MP, Rosen, S, Bii, M, Sigei, C, Shaffer, D, Sawe, F, Wasunna, M & Simon, JL, 2008. Early effects of antiretroviral therapy on work performance: Preliminary results from a cohort study of Kenyan agricultural workers. AIDS 22(3), 421–425.

- Larson, BA, Fox, MP, Rosen, S, Bii, M, Sigei, C, Shaffer, D, Sawe, F, McCoy, K, Wasunna, M & Simon, JL, 2009. Do the socioeconomic impacts of antiretroviral therapy vary by gender? A longitudinal study of Kenyan agricultural worker employment outcomes. BMC Public Health 9, 240.

- Larson, BA, Fox, MP, Bii, M, Rosen, S, Rohr, J, Shaffer, D, Sawe, F, Wasunna, M & Simon, JL, 2013. Antiretroviral therapy, labor productivity, and gender: A longitudinal cohort study of tea pluckers in Kenya. AIDS 27(1), 115–123.

- Lem, M, Moore, D, Marion, S, Bonner, S, Chan, K, O’Connell, J, Montaner, JSG & Hogg, R, 2005. Back to work: Correlates of employment among persons receiving active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care 17(6), 740–746.

- Linnemayr, S, Glick, P, Kityo, C, Mugyeni, P & Wagner, G, 2013. Prospective Cohort study of the impact of antiretroviral therapy on employment outcomes among HIV clients in Uganda. AIDS PATIENT CARE and STDs 27(12), 707–714.

- Liu, GG, Guo, JJ & Smith, SR, 2004. Economics costs to business of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Pharmacoeconomics 22(18), 1181–1194.

- Louwagie, GM, Bachmann, MO, Meyer, K, Booysen, FleR, Fairall, LR & Heunis, C, 2007. Highly active antiretroviral treatment and health related quality of life in South African adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A cross-sectional analytical study. BMC Public Health 7, 244.

- Maguire, CP, McNally, CJ, Britton, PJ, Werth, JL & Borges, NJ, 2008. Challenges of work: Voices of persons with HIV disease. Counselling and Psychology 36(1), 42–89.

- Martin, DJ, Chernoff, RA & Buitron, M, 2005. Tailoring a vocational rehabilitation program to the needs of people with HIV/AIDS: The Harbor-UCLA experience. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 22, 95–103.

- Martin, DJ, Steckart, MJ & Arns, PG, 2006a. Returning to work with HIV/AIDS: A qualitative study. Work 27, 209–219.

- Martin, DJ, Arns, PG, Batterham, PJ, Afifi, AA & Steckart, MJ, 2006b. Workforce entry for people with HIV/AIDS: Intervention effects and predictors of success. Work 27, 221–233.

- McDonald, S & Roberts, J, 2006. AIDS and economic growth: A human capital approach. Journal of Development Economics 80(1), 228–250.

- McGinn, F, Gahagan, J & Gibson, E, 2005. Back to work: Vocational issues and strategies for Canadians living with HIV/AIDS. Work 25, 163–171.

- Morineau, G, Vun, MC, Barennes, H, Wolf, RC, Song, N, Prybylski, D & Chawalit, N, 2009. Survival and quality of life among HIV-positive people on antiretroviral therapy in Cambodia. AIDS PATIENT CARE and STDs 23(8), 669–677.

- Nattrass, N, 2003. AIDS, economic growth and income distribution in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics 71(3), 428–454.

- Nicholls, S, McLean, R, Henry, KTR & Camara, B, 2000. Modelling the macroeconomic impact of HIV/AIDS in the English speaking Carribean. South African Journal of Economics 68(5), 405–412.

- Okezie, CA, Onyekanma, A & Baharuddin, AH, 2011. Impact of human immune deficiency virus and acquired immune deficiency syndrome on farm households. American Journal of Infectious Diseases 7(2), 32–39.

- Oloo, CA & Ojwang, C, 2010. The impact of HIV/AIDS on micro-enterprise development in Kenya: A study of Obunga Slum in Kisumu. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences 5(14), 927–931.

- Presnell, S, 2006. Return to work for individuals with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) disease: Dichotomous outcome variable or personally-constructed narrative challenge. Work 27, 305–312.

- Razzano, LA, Hamilton, MM & Perloff, JK, 2006. Work status, benefits, and financial resources among people with HIV/AIDS. Work 27, 235–245.

- Resch, S, Korenromp, E, Stover, J, Blakley, M, Krubiner, C, Thorien, K, Hecht, R & Atun, R, 2011. Economic Returns to investment in AIDS treatment in low and middle income countries. PLoS ONE 6(10), e25310.

- Rosen, S, 2004. The cost of HIV/AIDS to businesses in Southern Africa. AIDS 18(2), 317–324.

- Rosen, S, Ketlhapile, M, Sanne, I & DeSilva, MB, 2008. Differences in normal activities, job performance and symptom prevalence between patients not yet on antiretroviral therapy and patients initiating therapy in South Africa. AIDS 22(Suppl. 1), S131–S139.

- Rosen, S, Larson, B, Brennan, A, Long, L, Fox, M, Mongwenyana, C, Ketlhapile, M & Sanne, I, 2010. Economic outcomes of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in South Africa are sustained through three years on treatment. Plos ONE 5(9), e12731.

- Rosen, S, Larson, B, Rohr, J, Sanne, I, Mongwenyana, C, Brennan, AT & Galárraga, O, 2014. Effect of antiretroviral therapy on patients’ economic well being: Five-year follow-up. AIDS 28, 417–424.

- Salz, F, 2001. HIV/AIDS and work: the implications for occupational therapy. Work 16, 269–272.

- Schwarcz, S, Richards, TA, Frank, H, Wenzel, C, Hsu, LC, Chin, CS, Murphy, J & Dilley, J, 2011. Identifying barriers to HIV testing: Personal and contextual factors associated with late HIV testing. AIDS Care 23(7), 892–900.

- Sendi, P, Schellenberg, F, Ungsedhapand, C, Kaufmann, GR, Bucher, HC, Weber, R, Battegay, M & the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, 2004. Productivity costs and determinants of productivity in HIV-Infected Patients. Clinical Therapeutics 26(5), 791–800.

- Statistics South Africa, 2007–08. South African Labour Force Survey (LFS). Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Thirumurthy, H, Zivin, JG & Goldstein, M, 2008. The economic impact of AIDS treatment: Labor supply in Western Kenya. Journal of Human Resources 43, 511–552.

- Thirumurthy, H & Zivin, JG, 2012. Health and labor supply in the context of HIV/AIDS: The long-run economic impacts on antiretroviral therapy. Economic Development and Cultural Change 61(1), 73–96.

- Thirumurthy, H, Chamie, G, Jain, V, Kabami, J, Kwarisiima, D, Clark, TD, Geng, E, Petersen, ML, Charlebois, ED, Kamya, MR, Havlir, DV & the SEARCH Collaboration, 2013. Improved employment and education outcomes in households of HIV-infected adults with high CD4 counts: Evidence from a community health campaign in Uganda. AIDS 27(4), 627–634.

- Van Zyl, G & Lubisi, C, 2009. HIV/AIDS in the workplace and the impact on firm efficiency and firm competitiveness: The South African manufacturing industry as a case study. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 7(1), 1–14.

- Venkataramani, AS, Thirumurthy, H, Haberer, JE, Il, YB, Siedner, MJ, Kembabazi, A, Hunt, PW, Martin, JN, Bangsberg, DR & Tsai, AC, 2014. CD4+ cell count at antiretroviral therapy initiation and economic restoration in rural Uganda. AIDS 28(8), 1221–1226.

- Ventelou, B, Moatti, J-P, Videau, Y & Kazatchkine, M, 2008. ‘Time is costly’: Modelling the macroeconomic impact of scaling-up antiretroviral treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 22(1), 107–113.

- Ventelou, B, Arrighi, Y, Greener, R, Lamontagne, E, Carrieri, P & Moatti, JP, 2012. The macroeconomic consequences of renouncing to universal access to antiretroviral treatment for HIV in Africa: A micro-simulation model. PLoS ONE 7(4), e34101.

- Wagner, G, Ryan, G, Huynh, A, Kityo, C & Mugyenyi, P, 2009. A qualitative analysis of the economic impact of HIV and antiretroviral therapy on individuals and households in Uganda. AIDS PATIENT CARE and STDs 23(9), 793–798.

- Worthington, C, O’Brien, K, Zack, E, Mckee, E & Oliver, B, 2012. Enhancing labour force participation for people living with HIV: A multi-perspective summary of the research evidence. Aids & Behavior 16, 231–243.

- Wouters, E, Van Loon, F, Van Rensburg, D & Meulemans, H, 2009. State of the ART: Clinical efficacy and improved quality of life in the public antiretroviral treatment program, Free state province, South Africa. AIDS Care 21(11), 1401–1411.