ABSTRACT

Rural transportation in sub-Saharan Africa is a complicated and often contradictory endeavour. This article presents the results of an Internet-based survey deployed to elicit expert input on rural transport health and safety issues. The survey was specifically aimed at capturing priorities and opinions with regard to potential research needs. A total of 65 responses to the survey were received from transport and public health professionals from 25 countries across five continents. Descriptive analysis of the responses revealed varying concerns and priorities across different issues reflecting underlying themes of poverty and gender. Cluster analyses showed the complexities of interrelationships among issues. The results can form the basis for future studies and discussions needed to continue addressing the myriad transport-related issues impeding development in sub-Saharan Africa.

1. Introduction

No doubt the provision of transport infrastructure and services is important to economic growth, social inclusion and, even, political stability – all three of which are related to improved public health (Howe & Richards, Citation1984; Ellis & Hine, Citation1998; Starkey et al., Citation2002; Starkey, Citation2007; Banjo et al., Citation2012; Jones & Walsh, Citation2013; Porter, Citation2014). Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa has made considerable public health progress (reduced mortality and extended life expectancy) in the last few decades (IHME, Citation2013). Unfortunately, increased mobility – especially that related to higher speed vehicular travel – has resulted in increased injuries and fatalities from road crashes. Further, negative health outcomes (e.g. heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, lower respiratory infections) are attributable to air pollution from vehicles and are an increasing burden. A recent high-level report entitled Transport for Health concluded that road crashes and exposure to traffic-generated air pollution were among the top 10 leading causes of death across sub-Saharan Africa. It also noted, however, significant data availability and quality issues – for example, under-reporting of road injuries across sub-Saharan Africa of more than 500% (GRSF, Citation2014). The data issues are especially problematic in the rural context where crashes are more likely to go under-reported (even unreported) and there is less local-level pollution and exposure data available.

Such significant data challenges impede the development of effective, evidence-based solutions. Despite these challenges, myriad organisational, agency and individual experts work tirelessly in the field to improve the health and safety throughout rural sub-Saharan Africa. The purpose of the study presented herein was to increase the development-related knowledge of the complex health and safety issues related to rural transport in sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, this article presents the results of an Internet-based survey deployed to elicit insight from field experts. The survey was intended to collect and synthesise insight into related themes and issues identified in recent studies (e.g. Transport for Health; GSRF, Citation2014) and relevant research literature. The survey was specifically aimed at capturing priorities and opinions with regard to potential research needs relative to rural transport health and safety in sub-Saharan Africa.

In the following section, a brief summary of the literature review conducted to develop the context for the development of specific research questions is presented. The methodology to develop and administer the Internet survey is then described and followed by a detailed analysis of the results.

2. Literature review

The literature review began with the Transport for Health (GRSF, Citation2014) report and several other high-level studies linking transport and public health (Downing & Sethi, Citation2001; Freeman & Mathur, Citation2008; IHME, Citation2013) to establish major themes on which to focus a more targeted review of academic and other research literature. The detailed review provided the context for the development of specific research questions as summarised by some of the key findings presented in . A complete review of relevant literature including an extensive annotated bibliography can be found in Jones et al. (Citation2014).

Table 1. Key points derived from the literature on which survey questions were based.

3. Methodology

An Internet-based survey containing 13 questions was developed to capture expert input with regard to the themes identified in the literature and summarised in .Footnote1 The survey questions were tested with international colleagues for clarity and directness, and were modified based on feedback. Survey respondents were recruited via snowball sampling. Additionally, the survey was distributed to the Africa Community Access ProgrammeFootnote2 (AFCAP) Community of Practice by email (and recipients were encouraged to share the survey with their own colleagues as appropriate). The survey was also posted on the AFCAP LinkedIn Group and Twitter feed. Distributing the survey in such a way was intended to ensure meaningful responses from interested experts as well as diversify the range of professional input (Page, Citation2008). The survey contained multiple-choice questions that allowed respondents to indicate (and rank) issues they deemed important. Comment fields were provided to allow for optional detailed input not explicitly addressed in the structured question format. The survey responses were downloaded and analysed using basic spreadsheet operations and the R statistical analysis package (R Core Team, Citation2014).

4. Summary survey results

A total of 65 responses to the survey were received from 25 countries located on five continents.Footnote3 The first three survey questions were intended to give context for the technical information provided in the survey. Summary results for each survey question are presented in the following sections. The analysis of the results begins with traffic safety-related questions and progresses on to research the pollution attributable to transportation sources. Because the literature (refer to ) emphasises that there are numerous positive health impacts associated with increased mobility through transport, a final set of questions are presented that garner expert input on the relative importance of different types of access.

4.1. Questions 1 to 3 – Respondent information

To gauge the geographic range of expertise provided by the survey, the first question asked respondents to list the sub-Saharan African countries in which they have professional experience. illustrates the level of geographic diversity of input captured in the survey by Question 1. The second and third questions allowed respondents to report the type of organisation they represented and their area of specialty, and are reported in and , respectively.

Figure 1. The sub-Saharan Africa countries in which internet survey respondents noted professional experience.

Figure 2. Summary of professional affiliations of respondents. Note: NGO = non-governmental organisation.

There was a broad range of professionals represented among the Internet survey respondents. A plurality indicated that they were affiliated with a governmental agency of some type, with private consultants second. Among those that indicated ‘Other’, four respondents were with an international development agency and one identified himself or herself as a ‘passenger transport service provider’. Road-safety professionals accounted for 30% of survey responses. About two-thirds of respondents indicated ‘Other’ as their professional specialty, including policy analysts, public-health professionals, transport planners, transport engineers, economists, social scientists, a public-transport service provider, an institutional reform and development specialist, and an intermediate transport specialist.

4.2. Question 4 – Relative danger of transport modes

The first technical opinion question, Question 4, was aimed at establishing a relative level of perceived risk attributed to three classes of rural road users:

Vulnerable road users (pedestrians, bicyclists, handcarts, animal carts, etc.).

Transport services (buses and minibuses).

Motorcycles (including motorcycle taxis).

This relative dangerousness was expressed as follows:

Most dangerous (weight = 5).

Dangerous (weight = 3).

Least dangerous (weight = 1).

The raw results for Question 4 are summarised in (note that the precise wording of each survey question is provided in the title of the figure summarising its results). The average overall weightings are presented in . Both indicate that motorcycles are considered the biggest threat to rural road safety. The results for vulnerable road users and transport services were quite similar for the first two categories but more respondents assigned ‘most dangerous’ to vulnerable road users than to transport services. The comments submitted with this question reinforced the issue of the lack of training and regulation for motorcyclists:

Motorcycles are the most dangerous mode owing to poor skilled riders with little understanding of traffic rules and regulations coupled with poor road infrastructure …

Table 2. Overall average weightings for Question 4.

Lack of safety education and awareness was also cited as a major problem with respect to vulnerable road users. Regardless of motorcycles being deemed the most dangerous mode, their utility in the rural environment was emphasised in the comments:

In rural areas community members mostly pointed out that they feel more unsafe when on a motorcycle than a four wheeled vehicle. Motorcycles are unregulated (in some areas they are banned by local authorities), drivers lack training, they are very young and majority do not have licenses. These are some of the concerns among local community members there but on the other hand they are full of praises for motorcycles on how they are affordable, quick and reliable especially during the rainy season. Once safety is addressed, motorcycles will always be the best option.

Respondents rated vulnerable road users and transport services similarly in terms of their perceived risk. Such a result was not unexpected but the detailed comments provide deeper insight into the thinking and, more importantly, the complexity underlying the quantitative ratings:

Vulnerable road users are usually victimised because of the levels of education by other road users.

Most cyclists don’t have training on road safety. Enforcement on buses and minibuses transport services is low.

Too many minibuses has created scramble for passengers resulting in total disregard of road rules and regulations. Most minibuses are imported as Cargo vehicles and fitted with crude makeshift seats which have not passed stringent safety checks.

Bus crashes make the headlines, because dozens of people die in one go. But the numbers that die in bus crashes are fewer than the numbers of vulnerable road users and motorcyclists who die.

Transport Services are most dangerous for the following main reasons: unregulated and no enforcement (speed, overloading, poor driver training) …

4.3. Question 5 – Road conditions

The relationship between transport infrastructure and safety is well established (e.g. WHO, Citation2009) and it is known that poor infrastructure conditions in sub-Saharan Africa contribute to traffic accidents (e.g. WHO, Citation2013). Question 5 allowed respondents to indicate the level of importance they placed on three distinct aspects of road conditions that surfaced in the literature review. Question 5 asked ‘To the extent that road conditions contribute to rural road crashes in Africa, which of the following issues need research attention’:

Condition of travelway (e.g. potholes and ruts that can cause vehicles to lose control or encourage drivers to leave their travel lane to avoid hitting).

Lack of adequate signage (e.g. warning signs for horizontal curves or other approaching hazards).

Dust from unpaved roads obscuring visibility or resulting in risky driving behaviour (e.g. overtaking vehicles to avoid following along in their dust).

Respondents were asked to rate each of the three conditions according to the scale set out in . The range of responses are summarised in and the weighted responses are presented in .

Table 3. Research needs scoring.

Table 4. Overall average weightings for Question 5.

Lack of adequate signage and road condition received the same number of ‘very important’ rankings, and signage had two more ‘important’ responses than road condition. shows a higher-level importance placed on the operational condition of roads as dictated by traffic control and warning devices than on the physical condition of roads. In addition to the relative importance expressed, comments submitted with responses to Question 5 consistently emphasised roadway design:

In my view the [largest] contributor is the road condition, designs are poor (inadequate geometrics or do not conform to the surrounding topography resulting in limited sight distances and/or longer straight and steep sections on single 2-way carriageways leading to head-on collisions); others are inadequate signage (and/or vandalism of signage overtime) and poor riding surface (slippery surfaces when wet).

What about the road design/layout in general, which does not cater for vulnerable road users (pedestrians forced to walk on the road)?

In particular, the need to consider vulnerable road users in design (e.g. overall width, provision of shoulders, footpaths) was emphasised. One commenter noted the importance of adequate drainage to preserving safe road surface conditions. The need to assess the role of different surface treatments (from unpaved to fully sealed) was addressed in the comments from both the perspective of different road user experiences (i.e. motorcycles) and dust control as it relates to visibility and safety:

While I was a researcher, I participated in numerous studies regarding how method of construction, construction material, traffic, axle load, terrain, environment etc, will affect the performance of road, riding quality, gravel loss, dust pollution etc. In the course of this study, I was able to infer the negative impacts of dust and riding quality on road crash and accidents despite the rate of accidents and crashes was not substantiated with analytic methods as it was not part of the study. Thus, in my view, dust from unpaved roads and riding quality (paved & unpaved) plays a major role in road crashes and accidents in Ethiopia.

Two respondents explicitly addressed the need for a systematic approach to safety provision. One suggested the widespread adoption of safety-oriented, low-volume road design standards. The other proposed a more scientific approach aimed at evaluating the direct safety benefits associated with specific countermeasures (e.g. improved signage, pedestrian accommodations):

The low volume road manual (inclusive of road safety) should be published to assist road agency of other African countries on reducing cost in construction of rural roads. References can be made from countries like Zimbabwe the pioneers of Africa low volume roads (rural roads) research in 1986–1995 funded by TRL, SWISSROADS and ILO.

These issues are not key for me. More important would be understanding the relationship between different road characteristics and crash risk. Also the relative effectiveness of different remedial treatments on crash reduction (e.g. what is the impact of installing a pedestrian crossing facility/what is the impact of improved signing/what is the impact of different intersection types?). If you move more towards a safe system approach you would focus on the aspects of road design/layout that contribute to high severity and fatal crashes in terms of the outcome of the injuries sustained.

The issue of education and training was again raised. One commenter noted that road users do not understand the risks associated with different roadway environments. Other comments to Question 5 addressed specific issues such as the need for driver training/licensing programmes to increase awareness of road-related issues and for vulnerable road users (animal carts were singled out) to appreciate and utilise reflective clothing and markings in unlit conditions. Another respondent stated that the need for education and training extends well beyond road users:

Much as lack of adequate signage on these rural roads is a road safety concern, simply installing them doesn’t necessarily reduce the extent of the problem. Again, due to lack of road safety knowledge among these drivers and other road users. It is very interesting to know how that these very frequent road users do not understand what most of these signs mean. Engineers put them on the ground but so far there is little that is done to sensitise people on what these signs warn against.

Above all, professionalisation of the Transport industry must be a priority addressing the safety attitudes of all road users via education programmes. No amount of filling in potholes will stop the carnage without education programmes aimed at All stakeholders – Not just drivers. Without addressing Attitudes, no amount of improvement in road conditions with stop the road deaths and injuries – in fact better roads will lead to more deaths due to speeding.

4.4. Question 6 – Driving behaviour

Question 6 was included to allow respondents to express which behavioural-related factors warrant research attention. Using the same importance scale already described for Question 5, experts were asked to convey the relative importance of five risky driving behaviours. and show the raw and weighted average responses, respectively.

Table 5. Overall average weightings for Question 6.

Both and illustrate the concern for all of the driving behaviours offered as choices in Question 6. Although similar (and related), issues of poor (i.e. untrained, inexperienced and unregulated) driving and aggressing (i.e. taking risks such as speeding and overtaking) received the highest quantitative rankings. These two categories were frequently addressed in the respondent comments, as was the recurring issue of a lack of adequate data to fully develop causal relationships on which to formulate and implement specific, evidenced-based actions and safety programmes:

All are important. Fortunately we know what the impact of these things are (perhaps with the exception of the first and last) … but what we don’t have is good quality data on prevalence of these behaviours and what can be done to effectively fix these issues.

All need immediate attention. At the moment there’s not enough data to know how to target behaviour change interventions. But our research has shown that, of the different behaviours listed, poor driving and aggressive driving are the areas in greatest need of being addressed.

The research has been done, we know what needs to be done, it’s just effective implementation of recommendations that is lacking.

With more roads being built for example in Uganda, with the absence to training and behaviour changing communications, road users in SSA are living the recipe for disaster. Urgent action is needed. The research has been done, we know what needs to be done, it’s just effective implementation of recommendations that is lacking.

Another noted that risky behaviour such as distracted driving will probably be an increasing concern in sub-Saharan Africa:

Rural Africa just like urban is seeing a huge increase in the use of mobile phones, apparently some of these drivers have mobile phones to easily communicate with their customers for picking them up etc, in the next five years though, the use of mobile phones in Africa (rural) will be very high increasing the safety risks among motorcycle drivers.

clearly reiterates the sense of urgency regarding education, outreach, training and effective regulation of rural transport system users. It also emphasises what has been communicated as increasingly prevalent risky behaviours (aggressing driving and impaired driving) – both of which are ultimately related to education and enforcement. While receiving the lowest ‘very important’ designations, concern over distracted driving increasing in rural areas was expressed by multiple respondents in the comments. The other comments focused on the need to improve driver education and licensing. One commenter noted that overloading of vehicles should be included among risky behaviours that need to be addressed. Another commenter mentioned the issue of corruption as negatively impacting effective licensing and regulation, and therefore safety.

4.5. Question 7 – Impacts on women and children

The impact of road crashes is devastating to both individual families and communities as whole. Many of the deaths and injuries remove working-age young men from the workforce, thus having dire economic consequences for their immediate family livelihoods as well as the overall potential productivity of their communities. Many of these young men are killed or injured while providing transport for themselves and others (minibus drivers, motorcycle taxi drivers, etc.). As such, much of the safety research needs surrounding men are covered in the general safety themes of driving behaviour, road condition, vehicle condition and so forth.

Women, on the other hand, are typically impacted in road crashes as passengers or as vulnerable road users (most often as pedestrians). The same can be said for children and there has been specific attention paid, both in the research as well as international campaigns, to the safety of children travelling to and from school. Question 7 was asked to gauge practitioner opinions on the extent to which women and children specifically warrant research attention. The results summarised in indicate that the majority of respondents are sensitive to the issues specific to women and children as a subset of road users in sub-Saharan Africa.

4.6. Question 8 – Rural air pollution exposure

The impacts and pathways of exposure to air pollution from roads and vehicles are well documented in the literature. Question 8 allowed respondents to indicate which of three potential pathways resulted in the most vulnerable exposures:

Most vulnerable (weight = 5).

Vulnerable (weight = 3).

Least vulnerable (weight = 1)

The range of responses is summarised in and the weighted responses are presented in .

Table 6. Overall average weightings for Question 8.

and show that respondents perceive occupants of roadside residences and business as in the most danger of air pollution exposure. The comments offered for Question 8 reflect opinions that the need for increased mobility and accessibility in rural areas currently outweighs the relative risks of exposure to air pollution attributable to vehicles and roads.

4.7. Question 9 – Rural road dust research needs

Question 9 asked respondents to indicate whether they believe that rural road dust (and other traffic-induced air pollution) warrants more research attention than it has received. The results shown in show that the majority (64%) believe more research is needed. Of the remaining one-third of respondents, only 10% indicated there has been adequate research while 26% offered no opinion on the matter.

4.8. Question 10 – Rural accessibility research needs

Question 10 assessed respondent opinions on the rural accessibility needs to provide context for further consideration of rural transport health and safety. Evidence of the importance of healthcare accessibility was evident throughout the literature and there is an obvious connection to health and safety. The accessibility of education and economic opportunity was also discussed in the literature as indirectly contributing to improved rural health and safety. shows that the professional opinion reflected the results from the literature, with more than two-thirds of respondents indicating healthcare access as the most pressing accessibility issue in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Internet survey was structured such that a response to Question 10 would lead the participant to a relevant follow-on question. For example, respondents who identified healthcare as the most pressing accessibility issue in Question 10 were given the opportunity to provide more detailed input on that issue (i.e. Question 11). Respondents who indicated education accessibility on Question 10 were directed to its follow on, labelled as Question 12. The respondents who indicated economic access as most important were asked to provide more detail in Question 13. While it would have been interesting to elicit detailed input on all three accessibility issues, the respondents were directed through the survey according to what they deemed most pressing in the interest of keeping the survey as brief as possible.

4.9. Question 11 – Healthcare accessibility research needs

Question 11 asked respondents to rank five areas of rural healthcare access with regard to their relative need for research attention. The range of responses to Question 11 shown in and indicates that maternal and pre-natal access was definitively viewed as the rural healthcare-related accessibility issue in most need of attention from the research community.

Table 7. Overall average weightings for Question 11.

Respondents were also given the opportunity to comment, and the following two comments illustrate some of the complexities underlying this issue – mainly one of providing accessibility (and availability) of healthcare workers in addition to the patients:

1. Access to healthcare is part of a basket of services that transport MUST link/make accessible. Should there be separate transport for day Patients and for commuter Workers? 2. How is planning in the developmental state ensure that access is equal to all social amenities and services?

Maternal deaths during child births is still high in most of Sub-Saharan Africa mostly because pregnant women cannot access hospitals easily and even children are hardly immunised regularly due to distances from nearest health centers. Improved access will likely impact positively in this area.

4.10. Question 12 – Education accessibility research needs

Similarly, those who indicated education as the most pressing rural access need were asked to indicate which of three specific areas they deemed most in need of research. The relative importance of each was indicated using the scale previously presented in . The raw responses for Question 12 are reported in and the weighted responses are summarised in .

Table 8. Overall average weightings for Question 12.

Interestingly, shows that research into the ‘provision of safer pedestrian facilities’ was deemed ‘important’ by more respondents; the weighted rankings presented in show that it ties with ‘provision of transport services’ while research into educational initiatives aimed empowering children to travel more safely was clearly seen as the most important of the three.

4.11. Question 13 – Economic accessibility research needs

Question 13 gave respondents who indicated economic access as the most pressing rural accessibility issue (in Question 10) the opportunity to provide more detail. Specifically, respondents directed to Question 13 were asked which of three economic-related activities affected or were affected by road safety. The three activities included those that directly involve rural residents in the economic activity (i.e. transport of agricultural goods to market and connectivity to service-sector employment). Transport related to natural resource extraction was included because initial conversations indicated goods haulage and particularly large trucks on inter-urban highways and some feeder roads. The choices allowed respondents to express one of the options that best described the perceived relationship between one of three economic activities and road safety. The results are summarised in .

The results in , not unexpectedly, indicate that there is a direct relationship perceived between the activities that directly involve rural residents. The safety impacts of vehicles moving bulk goods associated with areas of natural resources extraction, however, were clearly seen as indirect – reflecting comments referring to risky driving (speeding, overtaking) and deficient vehicle operating conditions. One respondent provided input on the economic impact of road crashes, stating:

Road safety definitely impacts upon economic growth since it is often quoted that 1–3% of GDP is lost because of road crashes. It has a very direct impact on health services. It is very much related to poverty since road traffic crashes disproportionately impact on young men (often breadwinners) and the loss of a bread winner can mean sustained poverty for generations within a family.

5. Additional analyses

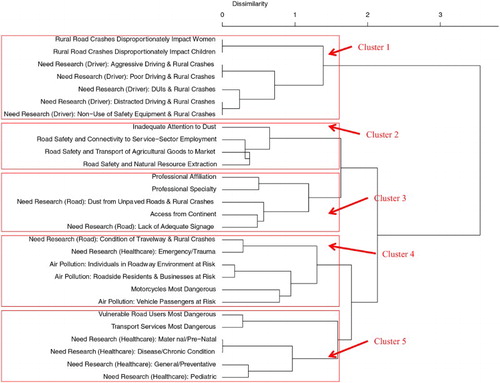

In addition to the summary results, the structure of the survey response dataset was explored at a higher level to identify potential relationships. An agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis (Hastie et al., Citation2009) was used to explore relationships among individual answers to the online survey questions as well as to the self-reported characteristics (e.g. affiliation, specialty). Each question response was treated as an individual variable and modelled as its own cluster; the algorithm then repeatedly joined the two clusters with the smallest dissimilarity until all of the variables (i.e. groups of answers) belong to a single cluster. Because the variables in the analysis are categorical, the following dissimilarity metric was used (Chavent et al., Citation2012):where

is the first eigenvalue obtained by applying PCAMIX (Kiers, Citation1991) to the cluster

. The implementation presented here used the ClustOfVar (Chavent et al., Citation2013) and dendextend (Galili, Citation2014) packages for R (R Core Team, Citation2014).

shows the complete hierarchical cluster for the survey data. The height of a cluster is the dissimilarity metric (measured across the top of ) for the component clusters

and

:

(Chavent et al., Citation2012). For simplicity, three to five clusters were considered for initial analysis. The mean adjusted Rand criterion (Hubert & Arabie, Citation1985) was bootstrapped 100 times and five clusters were chosen as indicated in the groupings shown in .

The shorter the segments connecting the clusters (and sub-clusters), the more similar those clusters are. For example, as seen at the top of Cluster 1, respondents who believe rural road crashes disproportionately affect women also tend to believe that rural road crashes disproportionately affect children, so their height is approximately zero. Similarly, Cluster 3 illustrates that there is a strong correlation between the respondent’s continent and belief that research into road/travel safety education and awareness for children and parents is needed – so the height of that sub-cluster is also approximately zero. But the correlation between these two clusters is weak, so the link between them is tall (approximately 3.5).

Most relationships revealed in are intuitive. The respondents answered questions in sets and those answers tend to be clustered together. For example, Question 13 asked respondents which groups are most at risk due to air pollution in rural Africa, and all three groups – occupants of roadside residences and businesses, individuals in the roadway environment, vehicle passengers – were placed in Cluster 4. There were, however, exceptions: the survey questions about road conditions (Question 5) splits across two clusters (Clusters 1 and 3), as do the questions about healthcare accessibility (Question 9 – Clusters 2 and 4) and the question about which mode is most dangerous (Clusters 2 and 3).

The effects of masculinity define Cluster 1. We know that men engage in more risky driving behaviour and women and children suffer for it, and this cluster includes the need for research about driver behaviours and the disproportionate impacts that rural road crashes have on women and children. There is something of a consensus about the need for research into these areas: over 90% of respondents believe there is a moderate to very important need for research into aggressive and poor driving, and 86% believe there is a moderate to very important need for research into distracted driving and non-use of safety equipment. The cluster also makes sense at a lower level. For example, of the 90% of respondents who believe children are disproportionately impacted by rural crashes, 63% also believe women are disproportionately affected; and of those who do not believe children are disproportionately affected, 86% also do not think women are disproportionately affected. Responses about the need for research into driver behaviours exhibit similarly strong patterns.

Cluster 2 includes economic accessibility research needs and opinions about whether dust and other air pollution have received adequate attention from the research and policy communities. About 80% of the respondents who think road safety has a strong or direct relationship to connecting people to service-sector employment in nearby areas also think road safety has a strong or direct relationship to transporting agricultural goods to market. Respondents did not think that natural-resource extraction is as important to road safety, but it still correlates (albeit negatively) with the other two economic accessibility questions. The more interesting link is between these three responses and ‘inadequate attention to dust’. The results suggest that respondents who believe that the policy and research communities have paid too little attention to dust are 1.5 times more likely to think transporting agricultural goods to market has a strong or direct relationship with road safety than those who have no opinion.

Cluster 3 includes information about respondent opinions on the need for research. It is no surprise that respondents with different specialties are affiliated with different organisations: environmental-protection experts are more likely to work for government agencies, universities or non-governmental organisations than for law enforcement. A respondent’s location also reveals something about affiliation – 18 of 19 respondents from government agencies were in Africa, but less than half of the private consultants were. Respondents who think the lack of adequate signage is an important source of rural crashes also tend to think that dust from unpaved roads harms road safety. Perhaps more surprising are the links between respondent backgrounds and opinions about road conditions. Four of five respondents in Africa think the lack of adequate signage is an important or very important source of rural crashes, but only one of three in Europe and the Americas agrees. Over 90% of respondents in Africa think dust from unpaved roads is a moderately important, important or very important contributor to rural crashes in sub-Saharan Africa, but only about 70% from Europe and the Americas agree.

Cluster 4 demonstrates the complexity of the issues at hand. It ties together questions related to air pollution exposure, motorcycle-related crash risks, research needed to address unsafe travelway conditions, and emergency and trauma accessibility. While it is difficult to identify (or even speculate) any underlying trend within this cluster, the intuitiveness of the sub-clusters suggests a rationality to the results: the condition of the travelway and rural crashes affect access to emergency/trauma care; if one thinks air pollution affects individuals in the roadway, it makes sense that one would also think air pollution affects people next to the roadway; and the two motorcycle-related answers cluster together. At a minimum, this cluster suggests the respondents believe that none of the issues at hand can entirely be considered alone.

Issues related to economic status appear to the define Cluster 5. Three distinct transport modes were considered in Question 4. The two modes more commonly associated with low-income populations (vulnerable road users and transport services) appear in Cluster 5 while the third mode (motorcycle) appears in another cluster. Several questions about transport access to health care that positively correlate with income also appear here in Cluster 5 (maternal/pre-natal, paediatric, disease/chronic condition), as well as one that negatively correlates (general/preventative).

6. Conclusion

This article reported results of an Internet survey of expert opinion regarding health and safety issues associated with rural transport in sub-Saharan Africa. Basic inspection of the responses revealed priorities and varying levels of concern across different issues. Further analyses showed the complexities of inter-relationships among issues as viewed by the respondents and their revealed common answers to certain questions. For example, the relationship of transport safety problems to gender-related issues suggests that education and enforcement policies targeted at male drivers could accrue extra benefits towards better conditions for rural women (and children).

The results of the survey both support and expound on elements identified across a wide range of literature. While these results only represent a small snapshot of professional opinion, it is believed that the described observations and relationships can form the basis for future studies and discussions needed to continue addressing the myriad transport-related issues impeding development in rural sub-Saharan Africa.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The questions are presented in numerical order (1 through 13) in and the results obtained from each question are summarised in the following individual sections. The actual wording of each individual survey question is provided at the top of each figure summarising its results.

2 AFCAP is a research programme, funded by the UK Department for International Development, with the aim of promoting safe and sustainable rural access for all people in Africa.

3 We determined the location of each respondent using Internet addresses and ipgeek.net. About two-thirds of respondents were in Africa – led by Tanzania, Malawi, Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia – but also some came from Europe (20%, led by the United Kingdom), North America (11%, led by the USA), Asia (2%, in Thailand) and Australia (2%).

References

- Abdulgafoor, M, Bachani, A, Koradia, P, Herbert, H, Mogere, S, Akungah, D, Nyamari, J, Osoro, E, Maina, W & Stevens, K, 2012. Road traffic injuries in Kenya: The health burden and risk factors in two districts. Traffic Injury Prevention 13(1), 24–30. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.629700

- Adesunkanmi, A, Oginni, L, Oyelami, O & Badru, O, 2000. Road traffic accidents to African children: Assessment of severity using the injury severity score (ISS). Injury 31(4), 225–8. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00236-3

- Bachoo, S, Bhagwanjee, A & Govender, K, 2013. The influence of anger, impulsivity, sensation seeking and driver attitudes on risky driving behaviour among post-graduate university students in Durban, South Africa. Accident Analysis and Prevention 55, 67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.02.021

- Banjo, G, Gordon, H & Riverson, J, 2012. Rural transport. Improving its contribution to growth and poverty reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa. SSATP, African Transport Policy Program, Working Paper No. 93. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Bryceson, D, 1993. Rural household transport in Africa: Reducing the burden on women? World Development 21(11), 1715–28. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(93)90079-O

- Bryceson, D, Mbara, T & Maunder, D, 2003. Livelihoods, daily mobility and poverty in sub-saharan Africa. Transport Reviews 23(2), 177–96. doi: 10.1080/01441640309891

- Chavent, M, Kuentz, V, Liquet, B & Saracco, J, 2012. ClustOfVar: An R package for the clustering of variables. Journal of Statistical Software 50(13), 1–16. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v50/i13, Accessed 12 July 2016. doi: 10.18637/jss.v050.i13

- Chavent, M, Kuentz, V, Liquet, B & Saracco, J, 2013. ClustOfVar: Clustering of Variables. R package version 0.8. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ClustOfVar, Accessed 12 July 2016.

- Damsere-Derry, J, Afukaar, F, Donkor, P & Mock, C, 2008. Assessment of vehicle speeds on different categories of roadways in Ghana. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion 15(2), 83–91. doi: 10.1080/17457300802048096

- Downing, A & Sethi, D, 2001. Health issues in transport and the implications for policy. PR/INT/238/2001, UK DfID, London, UK.

- Edvardsson, K, 2009. Gravel roads and dust suppression. Road Materials And Pavement Design 10(3), 439–69. doi: 10.1080/14680629.2009.9690209

- Ellis, S & Hine, J, 1998. The provision of rural transport services. SSATP Working Paper No. 37. The World Bank and Economic Commission for Africa.

- Ekpenyong, C, Ettebong, E, Akpan, E, Samson, T & Daniel, N, 2012. Urban city transportation mode and respiratory health effect of air pollution: A cross-sectional study among transit and non-transit workers in Nigeria. BMJ Open 2(5), e001253. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001253

- Freeman, P & Mathur, K, 2008. The health benefits of transport projects: A review of the world bank transport sector lending portfolio. IEG Working Paper 2008/2. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Galili, T, 2014. Dendextend: Extending R’s Dendrogram Functionality. R package version 0.17.5. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dendextend, Accessed 12 July 2016.

- van Gemert, F, Chavannes, N, Nabadda, N, Luzige, S, Kirenga, B, Eggermont, C, de Jong, C & van der Molen, T, 2013. Impact of chronic respiratory symptoms in a rural area of sub-Saharan Africa: An in-depth qualitative study in the Masindi district of Uganda. Primary Care Respiratory Journal 22(3), 300–5. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00064

- GSRF (Global Road Safety Facility), 2014. Transport for health: The global burden of disease from motorized road transport. The World Bank, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. IHME, Seattle, WA. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Greening, T & O’Neill, P, 2010. Traffic-generated dust from unpaved roads: An overview of impacts and options for control. 1st AFCAP Practitioners Conference, 23–25 November 2010.

- Hastie, T, Tibshirani, R & Friedman, J, 2009. The elements of statistical learning. 2nd edn. Springer, New York.

- Howe, J & Richards, P, 1984. Rural roads and poverty alleviation. Intermediate Technology Publications, London, UK.

- Hubert, L & Arabie, P, 1985. Comparing partitions. Journal of Classification 2(1), 193–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01908075

- IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Human Development Network, The World Bank). 2013. The global burden of disease: Generating evidence, guiding policy – Sub-Saharan Africa regional edition. IHME, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Jones, S, Tedla, E, Zephaniah, S, Appiah-Opoku, S, Tefe, M & Walsh, J, 2014. Rural transport health and safety in Sub-Saharan Africa. AFCAP GEN/127M, African Community Access Programme, UK Department for International Development.

- Jones, S & Walsh, J, 2013. Defining a post-conflict role for rural transport in Sub-Saharan Africa: A crosscutting literature review. AFCAP GEN/127B, African Community Access Programme, UK Department for International Development.

- Kiers, HAL, 1991. Simple structure in component analysis techniques for mixtures of qualitative and quantitative variables. Psychometrika 56(2), 197–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02294458

- Kinney, P, Gichuru, M, Volavka-Close, N, Ngo, N, Ndiba, P, Law, A, Gachanja, A, Gaita, S, Chillrud, S & Sclar, E, 2011. Traffic impacts on PM2.5 air quality in Nairobi, Kenya. Environmental Science & Policy 14(4), 369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2011.02.005

- Kiser, M, Samuel, J, Mclean, S, Muyco, A, Cairns, B & Charles, A, 2012. Epidemiology of pediatric injury in Malawi: Burden of disease and implications for prevention. International Journal of Surgery, 10(10), 611–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.10.004

- Kobus, H, 1980. Breathe analysis for control of drunk-driving in Zimbabwe Rhodesia. Central African Journal of Medicine 26, 21–7.

- Kumar, A, 2011. Understanding the emerging role of motorcycles in African cities. Apolitical economy perspective. SSATP Discussion Paper NO. 13, Urban Transport Series. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Lord, D, Abdou, H, N'Zue, A, Dionne, G & Laberge-Nadeau, C, 2003. Traffic safety diagnostics and application of countermeasures for rural roads in Burkina Faso. Transportation Research Record 1846, 39–43. doi: 10.3141/1846-07

- Madubueze, C, Chukwu, C, Omoke, N, Oyakhilome, O & Ozo, C, 2011. Road traffic injuries as seen in a Nigerian teaching hospital. International Orthopaedics 35(5), 743–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1080-y

- Manyara, C, 2013. Combating road traffic accidents in Kenya: A challenge for an emerging economy. Proceedings from the KESSA 2013 Conference, 6–7 September, Bowling Green, OH, USA.

- Mefire, A, Mballa, G, Kenfack, M, Juillard, C & Stevens, K, 2013. Hospital-based injury data from level III institution in Cameroon: Retrospective analysis of the present registration system. Injury-International Journal of the Care of the Injured 44(1), 139–43. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.026

- Mfinanga, D, 2014. Implication of pedestrians’ stated preference of certain attributes of crosswalks. Transport Policy 32, 156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.01.011

- Mupimpila, C, 2008. Aspects of road safety in Botswana. Development of Southern Africa 25(4), 425–35. doi: 10.1080/03768350802318506

- Musafiri, S, Joos, G & Van Meerbeeck, J, 2011. Asthma, atopy and COPD in sub-Saharan countries: The challenges. East African Journal of Public Health 8(2), 161–3.

- Mustapha, B, Blangiardo, M, Briggs, D & Hansell, A, 2011. Traffic air pollution and other risk factors for respiratory illness in schoolchildren in the Niger-delta region of Nigeria. Environmental Health Perspectives 119(10), 1478–82. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003099

- Nantulya, V & Reich, M, 2002. The neglected epidemic: Road traffic injuries in developing countries. Education and Debate 324, 1139–41.

- Odero, W, 1998. Alcohol-related road traffic injuries in Eldoret, Kenya. East African Medical Journal 75(12), 708–11.

- Odero, W, Khayesi, M & Heda, P, 2003. Road traffic injuries in Kenya: Magnitude, causes and status of intervention. Injury Control and Safety Promotion 10, 53–61. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.53.14103

- Ogazi, C & Edison, E, 2012. The drink driving situation in Nigeria. Traffic Injury Prevention 13(2), 115–9. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.645097

- Olubomehin, O, 2012. The development and impact of motorcycles as means of commercial transportation in Nigeria. Research on Humanities and Social Science 2(16), 231–9.

- Oluwadiya, K, Kolawale, I, Adegbehingbe, O, Olasinde, A, Agodirin, O & Uwaezouke, S, 2009. Motorcycle crash characteristics in Nigeria: Implication for control. Accident Analysis and Prevention 41, 294–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.12.002

- Page, S, 2008. The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Porter, G, 2002. Living in a walking world: Rural mobility and social equity issues in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 30(2), 285–300. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00106-1

- Porter, G, 2014. Transport services and their impact on poverty and growth in rural Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of recent research and future research needs. Transport Reviews 34(1), 25–45. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2013.865148

- Porter, G, Tewodros, A, Bifandimu, F, Gorman, M, Heslop, A, Sibale, E, Awadh, A & Kiswaga, L, 2013. Transport and mobility constraints in an aging population: Health and livelihood implications in rural Tanzania. Journal of Transport Geography 30, 161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.05.001

- R Core Team, 2014. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org, Accessed 12 July 2016.

- Starkey, P, 2007. The rapid assessment of rural transport services. A methodology for the rapid assessment of the key understanding required for informed transport planning. SSATP Working Paper No. 87-A.

- Starkey, P, Ellis, S, Hione, J & Ternell, A, 2002. Improving rural mobility. Options for developing motorized and nonmotorized transport is rural areas. World Bank Technical Paper No. 525. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Venn, A, Yemaneberhan, H, Lewis, S, Parry, E & Britton, J, 2005. Proximity of the home to roads and the risk of wheeze in an Ethiopian population. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62(6), 376–80. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.017228

- WHO (World Health Organisation), 2009. Global status report on road safety: Time for action.

- WHO (World Health Organisation), 2013. Road safety in the WHO African region: The facts 2013.