ABSTRACT

While the increased access to consumer credit has helped many families improve their welfare, the rising repayment burdens upon a background of chronically low saving rates have generated concerns that South African families are becoming ever more financially fragile and less able to meet their consumer debt repayment obligations. Using data from the Cape Area Panel Study, this article investigates whether consumer debt repayment problems are better explained by excessive spending which leaves households financially overstretched or by negative income shocks. The results indicate that households are significantly more likely to be delinquent on their financial obligations when they suffer negative events beyond their control rather than due to the size of the expenditure burden. This suggests that consumer repayment problems are likely to endure even when consumers borrow within their means. Thus, regulatory efforts to improve mechanisms for debt relief might be more meaningful than restrictions on lending.

1. Introduction

For many South Africans, the rising cost of living upon a background of increasing dependencies has meant that disproportionately large portions of household income are being committed to consumption expenditure rather than saving. While the increased access to credit helps families to supplement this consumption expenditure, the rising debt service burdens have brought forth concerns that families are becoming more financially fragile and less able to meet repayment obligations.

Consumer debt repayment performance is not only an important indicator of the financial health of the household sector, but also an influential driver of the consumer protection policy debate. In South Africa, the debate has tended to focus largely on the misbehaviours in the credit market wherein consumers are allowed to overextend themselves financially by borrowing beyond their means. In response, government policy has focused largely on ‘prevention’ of these misdeeds through the National Credit Act (NCA), with its relatively tougher stance, inter alia, on affordability evaluation, information and disclosure, and sanctions for reckless lending.

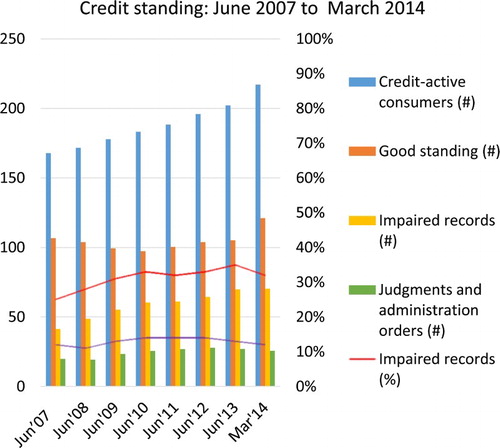

Despite these efforts, data from the National Credit RegulatorFootnote1 suggest that the average credit standing of consumers has only continued to deteriorate in tandem with rising incidences of litigation judgements and administration orders since June 2007 when the NCA came into full force (). Such a trend generates ominous feelings about the efficacy of regulatory interventions that restrict lending. After all, lenders are naturally loss averse and therefore should have an incentive to see that consumers only borrow what they can comfortably repay. Assuming that lenders adhere to the NCA’s strict lending regulations and painstakingly evaluate consumers’ creditworthiness, then delinquencies will be less likely to occur due to excessive borrowing but rather due to ex-post alterations in consumers’ income streams.

Figure 1. Credit standing of consumers (June 2007–March 2014). Source: Author’s own calculations from National Credit Regulator, Credit Bureau Monitor data.

Lenders might be able to quantify a consumer’s ability and willingness to repay the debt when due. However, they might not be able to predict whether a consumer will encounter negative situational changes which might render him/her incapable of committing to his/her repayment obligations. The concurrence of factors beyond lenders’ (and consumers’) control may trigger severe repayment difficulties even where consumers borrow within their means. This situation reinforces the notion that consumer debt delinquencies are more complex than the mere fact that consumers are spending money they do not have.

This contention is addressed by examining data on South African households. The key contribution is to establish whether consumer debt delinquencies are more likely to result from households spending excessively and rendering themselves financially overstretched or from unfortunate events that erode repayment capacity (e.g. becoming suddenly unemployed or divorced). Independently, these factors are particularly salient in light of the current government’s strong predisposition to consumer protection in the credit market and the discourses that underpin the regulatory positions taken (Ssebagala, Citation2015). While the dominant regulatory discourse has tended towards excessive spending ‒ resulting mainly from reckless lending and asymmetric information (see DTI, Citation2004) – alternative discourses that accentuate the importance of negative (often unanticipated) situational events have developed elsewhere. This line of thought embraces the notion that delinquencies (in respect of unsecured debt) might be more related to consumption smoothing than to consumer duplicity, and ultimately demonstrates that regulatory interventions need to be largely alleviative as opposed to punitive.

In terms of theory, consumer debt delinquency is non-strategic. Rather, it is a consequence of a genuine inability to pay when household resources become too strained to support the household’s ongoing subsistence while meeting scheduled repayments. This is related to the ‘cash flow’ theory of defaults,Footnote2 which is based on the assumption that debtors will avoid arrears so long as their income flows are sufficient to cover their debt repayments without undue financial burden (Alfaro et al., Citation2010). Hence, the behaviour of both the transitory income and monthly debt-service ratio should explain empirically the household’s overall repayment performance.

Following an empirical strategy similar to Peter & Peter (Citation2006) for the default risk of Australian home buyers, the study proceeds to examine the relative importance of excessive spending and negative income shock on borrowers’ delinquency in South Africa ‒ and then controlling for the assumption that some ‘types’ of households are more likely to repay their debts than others. The study progresses as follows: some existing literature on debt delinquency is presented next, followed by the data analysis and presentation of results, and then conclusions and implications. Throughout the article, the terms ‘delinquency’ and ‘repayment problems’ are mutually interchangeable to refer to the inability to pay due financial obligations or to be in arrears.

2. Literature review

There has been scanty formal analysis of consumer debt repayment performance in South Africa and that too has been based largely on small sample cross-sectional data, but there is substantial literature on the situation internationally. Generally, a number of studies have blamed consumer debt delinquency on lending and borrowing practices that allow some consumers to overburden themselves with more debt than they can comfortably afford. Predatory behaviours, often coupled with deceptively priced credit by lenders (Hill & Kozup, Citation2007), along with the lack of self-control, financial illiteracy or irrational optimism about future income are some of the specific behaviours cited in respect of consumers (e.g. Hurwitz & Luiz, Citation2007; Gathergood, Citation2012). Alternatively, ex-post misfortunes such as medical emergencies or sudden unemployment (often unanticipated during credit screening) have also been found to trigger repayment difficulties even where consumers have borrowed reasonable amounts (e.g. Getter, Citation2003; Grant, Citation2010).

Additionally, another stream of literature focuses on institutional factors to explain debt delinquencies across regions. Essentially, these studies contend that arrears might be strategic because they are disproportionately affected by variations in the efficacy of insolvency regulations and the possible legal and social costs thereof (e.g. Jentzsch & Riestra, Citation2006; Chatterjee et al., Citation2007), while others have modelled delinquencies on the propensity for bad loan origination and recovery, and the efficacy of predatory lending and information-sharing regulations (Ho & Pennington-Cross, Citation2006; Jappelli et al., Citation2008; Duygan-Bump & Grant, Citation2009).

2.1. Excessive spending

Some consumers will take on an unreasonable amount of debt and later find themselves financially overstretched and unable to repay (Zhu, Citation2011). Both demand-side and supply-side dynamics can be blamed.

On the demand side, psychological traits have been blamed for influencing consumer overindulgence. Consumers have been known to overestimate the immediate benefits of the credit on offer or to undervalue the cost of repayment (Meier & Sprenger, Citation2007; Heidhues & Kőszegi, Citation2010), whilst some simply harbour inflated expectations of future earnings (Bachmann et al., Citation2015). For others, a lack of self-control or a low level of financial knowledge might explain this untenable consumption (Hurwitz & Luiz, Citation2007; Gathergood, Citation2012). These traits have been identified among South African consumers where, for instance, Hurwitz & Luiz (Citation2007) found a cross-section of consumers who exhibited a reckless consumption culture even in the face of complete uncertainty, and that this was driven by short-sightedness, low levels of formal education and financial illiteracy (Citation2007:114). Conversely, Bertrand et al. (Citation2010) concluded (after a field experiment) that consumers’ self-control and decision-making were being impaired through psychologically manipulative credit marketing techniques. Gathergood (Citation2012) notes similar traits among UK consumers for whom, regardless of their levels of financial sophistication, self-control problems were fuelling impulse-driven consumption and a disproportionate use of quick-access credit products ‒ thereby overextending themselves (Citation2012:591).

On the supply side, lax lending criteria that might allow an already overstretched debtor to qualify for more debt, lenders’ non-disclosure of important credit information and other predatory practices have been major issues of contention in South Africa. Then there is the high cost of borrowing (including high interest rates, insurance and other non-interest charges) which inflates the repayment burden (e.g. James, Citation2012). The paradox, however, according to Bertrand et al. (Citation2010) is that the cost of borrowing will only have a negligible effect on consumer credit decision-making, especially among the low-income. Hurwitz & Luiz (Citation2007) note that most low-income debtors tend to ignore or are often unaware of how much interest they pay, or even fail to recognise predatory tendencies. Yet as observed by Hill & Kozup (Citation2007), predatory lending practices are most likely to be carried out to the detriment of the vulnerable and poor consumers, which could perhaps be attributed to the fact that these groups are disproportionately given to time-discounting in their desperation to make ends meet (see Haushofer & Fehr, Citation2014).

Obviously, whether excessive spending is related to demand-side dynamics or lax lending criteria, the policy implications are clear: explore viable pre-contractual regulatory mechanisms that restrict subprime lending and/or improve consumer decision-making (Ho & Pennington-Cross, Citation2006; Stoop, Citation2009).

Empirically, the relative effects of excessive spending on the debt repayment performance have been investigated using different proxies for the level of indebtedness, notably the size of the credit balance and credit limit (Gross & Souleles, Citation2002; Lopes, Citation2008), the number of credit commitments held (Whitley et al., Citation2004; Disney et al., Citation2008) or the debt-service ratio (Getter, Citation2003; Alfaro et al., Citation2010; Farinha & Lacerda, Citation2010). Getter (Citation2003) suggests that the debt-service ratio would be a more sound measure, because it allows for a more accurate comparison of the household’s immediate financial stress. Contrarily, Kennedy et al. (Citation2011) argue that a household’s expenses-to-income ratio would be a more inclusive measure of financial difficulty not only because household incomes are spent on much more than just debt repayment, but also because (based on the residual income) it reflects the possibility that even the reasonably high-income consumers can experience financial strain if their expenses escalate. It is worth noting, however, that the inability to find a universal indicator of excessive spending could be interpreted as a result of data limitations rather than a personal choice.

2.2. Socio-economic shocks

Even consumers who take on a ‘reasonable’ amount of debt, with every intention (and means) to repay may face repayment difficulties (Getter, Citation2003). Misfortunes or financially adverse events that every so often befall households cause substantial declines in income, which renders them suddenly incapable of committing to their repayment obligations (Himmelstein et al., Citation2005; Grant, Citation2010). Unfortunate interruptions in a household’s income stream and other trigger situations for which lenders or debtors have no control ‒ especially after a credit request has been granted ‒ often translate into sudden inability to committee to repayment schedules even for small claims (Getter, Citation2003). Even the more cautious households may find themselves hopelessly indebted if their incomes are disrupted by such emergencies as retrenchment or death of a family member (Hurwitz & Luiz, Citation2007).

In attempting to delineate the role of economic shock, Disney et al. (Citation2008) contend that adverse changes in debtors’ circumstances do not necessary have to result in massive shifts in earnings in order to trigger changes in economic behaviour; instead, the surprise factor matters more. Therefore, insofar as the plans of an economic agent are based on the current state of affairs, the economic outlook and expectations, any deviations from this state of affairs will affect the agent’s economic plans (Pesola, Citation2011). Some households may substantially reduce consumption or expenditure on basic necessities or renege of financial obligations as a coping mechanism. For instance, Knight et al. (Citation2015) observed that a large percentage of South African households which experienced shock (71%) reported substantial difficulty in buying or paying for basic needs, and in attempts to survive the immediate consequences of these shocks the households often deployed a variety of coping mechanisms: a number of which involved making trade-offs with negative knock-on effects for the household and its members. Certainly, suspending consumer debt repayment may represent one such trade-off.

Furthermore, insofar as sensitivity to shock can be informed from the economic environment in which an individual lives or works, family structure should provide some information on one’s credit risk (e.g. Avery et al., Citation2004). Family structures that exhibit higher rates of dependency and/or fewer income earners are not only correlated with a greater likelihood to use credit to finance the greater household consumption, but such families are also likely to struggle with budgeting problems (Hurwitz & Luiz, Citation2007). The situation is then compounded by the chronic inability to muster adequate financial buffering (e.g. Collins & Leibbrandt, Citation2007), thus increasing the delinquency risk (Alfaro et al., Citation2010; Grant, Citation2010). Shock exposure might also be affected by lifecycle factors such as the path and stability of labour income, itself affected by education and age (e.g. Lopes, Citation2008; Townley-Jones et al., Citation2008).

In summation, negative trigger events not only erode repayment capacity, but might also force consumers to act strategically to avoid jeopardising their ongoing subsistence. Consumers may be forced to suspend otherwise manageable obligations if they realise that continuing to pay might lead to further deterioration in their own and their dependents’ well-being. The possibility that consumers will suffer unfortunate events reduces the veracity of their economic information and/or credit history (at the time of determination) in ascertaining their credit risk, such that the possibility of delinquency becomes an inevitable feature of the credit system (Viimsalu, Citation2010). In essence, subject to their credit limits, borrowers will be able to carry safely as much debt as they desire, and their subsequent delinquency will only be contingent on them suffering unfortunate changes in their circumstances (Getter, Citation2003). Should consumers find themselves in such unfortunate situations, legal mechanisms to discharge their indebtedness become a practical necessity ‒ not only as a form of consumption insurance, but also to protect them from further adverse outcomes such as repossessions or wage garnishments (see Van Apeldoorn, Citation2008).

The current study contributes to this extant literature by testing whether debt problems of South African households can be traced to experiences of unfortunate events or excessive spending. Given the paucity of previous empirical studies on the debt repayment performance of South African households, the variables used for this analysis are, for the most part, drawn from studies of other countries. The current study is largely exploratory and is deliberately delimited to ‘consumer’ debt delinquency, knowing that consumer debt behaviours differ from housing or entrepreneurial debt behaviours due to the very nature of these debts. It is also useful to clarify that this is neither a study about ‘poverty’ in South Africa, nor of the different manifestations of households’ risk mitigation strategies.

3. The data and analysis

The study employed household data from Wave One (2002), Wave Three (2005) and Wave Four (2006) of the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS), a longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults in Cape Town, South Africa as they transition through youth to adulthood and other outcomes. The CAPS sample was designed inter alia to produce a household sample that when appropriately weighted would be a representative sample of households in metropolitan Cape Town, including both households with and without young adult residents (Lam et al., Citation2008). Based on the 1996 census Enumeration Areas, the selection of the original sample entailed a two-stage stratification wherein the first stage was the selection of sample clusters defined by the majority racial group within the neighbourhood. The second stage was the selection of households within each cluster. According to the 1996 Population Census, Metropolitan Cape Town included 4759 populated Enumeration Areas and using the weights provided by Statistics South Africa the population was 2 554 674, which represented 6.3% of the population of South Africa (Lam et al., Citation2008:8).

In addition to information about the young adults, the CAPS also collected information on their entire households including demographic characteristics, household income, expenditure and consumer debt performance. This is the information exploited for this study. To avoid possible biases that may result from attrition (of households), the sub-sample for this analysis comprises only those households on which information was successfully collected in all three waves (n = 2549). In particular, the key question is whether the household reports that it has been unable to make a scheduled payment on its consumer (non-housing) debt in the 12 months prior to the 2006 survey (yes = 1, otherwise = 0). Presumably the questionnaire respondents understood this question to refer to all consumer credit obligations, excluding any housing or business debt. Because this question could not capture the length (severity) of the delinquency problem, one cannot discount the possibility that in some of these cases the non-payment was transitory. Nevertheless, this study is grounded on the premise that delinquency has a wide definition: from bankruptcy at one extreme to being a few weeks behind on some payments at the other – whatever the case, lenders will view any late payment as a risk of default (see Grant, Citation2010:5).

presents a detailed definition of the variables of interest and their mean values for this sub-sample. Following Bikker & Metzemakers (Citation2005), the study defines negative shock as a surprise relative to expectation or as a negative situational change which might lead to an adverse shift in earnings, or increase claims on family resources. For the current study, the assumption is that a household’s repayment performance in one period (i.e. 2006) is a reaction to its circumstances or changes thereof in the preceding period (derived from the 2002 and 2005 waves of the CAPS) rather than random behaviour. The variables selected to depict negative shock were income shock (i.e. 2005 household income lower than 2002 income), random shock (e.g. job loss, death or illness), expenditure shock and increase in family size ‒ seen in the context of increased claims on family resources, because so often adults and children move between households to access food, care or other resources (see Seekings & Nattrass, Citation2008:40). A subjective measure of ‘financial worries’ was also included to gauge the interaction between life satisfaction and repayment performance. Admittedly, there is a potential reverse causality problem that financial worries might result from the perceived inability to satisfy impending obligations.

Table 1. Variable definition, sample mean values and expected signs (n = 2549).

It should be noted that whether the shock was unanticipated or otherwise remains precisely obscure with these data, although disaggregating this aspect (where possible) would provide more insight into to whether households actually prioritise resources or make tougher sacrifices. Nonetheless, the overarching aim was to test whether negative changes in a family’s circumstances might have a profound effect on its debt sustainability.

Following Kennedy et al. (Citation2011), and Saunders & Hill (Citation2008) on Irish and Australian households respectively, the variable depicting excessive spending was measured as the ratio of the household’s total monthly expenditure (excluding housing-related payments) to the household’s gross monthly income (expenses-to-income) ‒ truncated to between the 1st and the 99th percentile to eliminate extreme outliers. Expenses-to-income ratio is the standard level of the household’s expenditure on commodities and services, and therefore represents not only the relative living standards of households, but also the overall level of financial strain. It is also a more inclusive indicator of the current household expenditure burden (Saunders, Citation2011) as opposed to the debt-to-income ratio which, despite its ubiquitous use, does not account for non-debt expenditures.

Based on Katona’s (Citation1960) exposition of ‘ability to borrow’, which suggests that some households are more likely to repay their financial obligations than others (see Zhu & Meeks, Citation1994; Roos, Citation2008), the study controls for some variables related to credit quality (i.e. monthly per-capita income, financial buffers and homeownership). While the financial buffers available in the data are quite modest (i.e. having a saving account and/or life insurance), it should be noted that, in South Africa, even with recent market expansions, access to these is still far from ubiquitous and, assuming all else is equal, suggests some degree of financial sophistication.

It is revealed that 18% of the sub-sample reported being in arrears on their consumer debts in 2006. Between 2002 and 2005, 53% (1342) of the 2549 households experienced negative incomes while 66% experienced increases in expenditure during the same period. Households that reported experiencing random negative events (prior to the 2005 survey) which may have impacted on their financial situations (e.g. a job loss) were 19% of the sub-sample. On average, the sampled households spent 65% of their incomes on general household expenditures including consumer debt repayment.

Descriptive statistics were examined for each variable of interest and are presented in , including the distribution of household characteristics and measures of association between these characteristics and the binary dependent variable. The distribution of characteristics among the delinquent and non-delinquent households is presented as mean values. The bivariate correlation coefficients (Corr) identify the relationship between the binary dependent variable and the individual independent variables, while the chi-square tests for significance (p*) represent the measures of the strength of these relationships. A statistically significant p value (p < 0.05) suggests that one of the categories of a variable depicting household characteristics is statistically significantly different from one of the categories of the dependent variable.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of key variables for delinquent and non-delinquent samples (n= 2549).

The underlying problem is whether a household fails to repay its due financial obligations and whether this can be traced to ‘excessive’ spending or to financially adverse events ‒ in the preceding period. The bivariate relationships presented in show a significantly positive correlation between arrears and experiences of income shock, random negative shock, increase in expenditure and increase in household size (p < 0.05). Households who self-reported financial distress were significantly more likely to be in arrears on their consumer debts (72%) than those who did not (66%). No relationship was observed between the household’s expenses-to-income ratio and delinquency. Of the three indicators of credit quality, only homeownership revealed a significant relationship with delinquency: suggesting intuitively that homeowners represent positive consumer credit quality.

Overall, the first signs presented by the bivariate relationships seem to suggest that consumer debt delinquencies are more related to experiences of adverse events than the level of the household’s expenditure. Naturally, such unfortunate events disrupt consumers’ income streams but the fact that consumers might not have anticipated these events at the time of the credit request might be even more binding. Thus, while consumers might wish to sustain a certain (safe) level of indebtedness, the prevalence of unfortunate events may prevent them from achieving that.

3.1. Logistic regression analysis

What matters more for consumer debt delinquencies: excessive spending that renders borrowers financially overstretched or shocks to income that erode repayment capacity? Because there is a definable probability that (based on their characteristics) individuals will become delinquent in their financial obligations (see Greene Citation1998), this dichotomous outcome (delinquent or non-delinquent) can only be reliably generated by probabilistic models, such as logit or probit. For this study, binary dependent variable logit regression models were estimated to test whether a household’s reaction to circumstances over a certain period (t) affects its repayment performance over the following period (t + 1). One important consideration is the timing of the delinquency and of the negative event, and the spending. For instance, consider a job loss. Households may become delinquent and become unemployed at the same time. To address this endogeneity issue, a dynamic specification is employed in which the relationship is investigated between arrears between time t and t + 1 and household characteristics between time t – 1 and t.

The relationship estimated takes the general form:(1) where the dependent variable

is binary, taking the value of one if household i was delinquent at a period t and t + 1 (in the 12 months preceding the 2006 survey), and zero otherwise. The independent variables which represent household circumstances reported during an earlier period t – 1 and t (2002 and 2005) are represented by

, while

is the vector of their coefficients and

is the idiosyncratic error (either time-variant or time-invariant). There are three groups of independent variables (negative shocks, expenses-to-income ratio and ability to borrow), such that the delinquency risk of a household is represented by:

(2) where X1 is the matrix of shock effects, X2 is the matrix of measures of excessive spending, X3 is the matrix of ability to borrow and ε is the error term.

If is large enough in relation to these characteristics, then the household is delinquent on their consumer debts and this probability is represented by:

(3) If the error term is normally distributed (i.e. mean zero and variance one), then the delinquency probability should be expressed as:

(4) where

is the standard normal cumulative distribution function (see Evans et al., Citation2000), classified as:

(5) To test the effect of excessive spending on repayment performance, quintiles of the household expenditure burden (expenses-to-income ratio) were created to see whether households at the top of the distribution of the expenditure burden are more likely to experience repayment difficulties. Breaking the variable into quintiles reduces the likelihood of heteroscedasticity in the regression analysis. The sources of financial strain are represented by dummies for income shock, random shock, expenditure shock, increase in family size and subjective financial worries.

In addition, some modest credit quality-related effects (i.e. homeownership, financial buffers and per-capita income) are included in the analysis to control for ‘ability to borrow’. In essence, the model estimated is a combination of household characteristics visible to lenders in credit applications and the unobservable characteristics (i.e. economic shocks) which should affect the size of the error term in lenders’ credit scoring algorithms.

Multivariate logistic regression models are specified in a framework which assumes that market behaviours are prudent. Lenders therefore apply their due diligence and borrowers can only qualify for as much they can repay (giving regard to their circumstance at the time of determination), such that subsequent repayment difficulties will not result from ‘excessive’ spending by these consumers, but rather from financially adverse events following the granting of the credit. In such a framework, the level of consumption will only be indicative of the ability to borrow ‒ subject to idiosyncratic constraints. Hence the coefficients at the top of the distribution of the expenses-to-income ratio, if significant, are expected to be negative.

Households are more likely to be in arrears if they experienced financially adverse events. Therefore, the coefficients for income shock, random shock, expenditure shock, increase in family size and subjective financial worries are expected to be positive. Having to contend with an unusually higher number of dependents or having a profound dissatisfaction with personal finances should have the same effect as other factors that disrupt the income stream. Finally, repayment difficulties are expected to be negatively related to homeownership, financial buffers and per-capita income because these are correlated with wealth.

3.2. Results

The logistic regression results are presented in , including their marginal effects. Since the explanatory power of the selected variables on the probability of delinquency might vary based on whatever combination of parameters are estimated in the logistic model, their individual effects are illustrated using marginal effects (). The marginal effects show the effects of each of the predictors relative to a particular type of debtor (i.e. the base case: depicting movement from zero to one for the binary predictors and the mean values for the per-capita income and financial buffers).

Table 3. Default risk logistic model for income shock and excessive spending.

The first three columns represent the main default risk model, wherein default risk is informed by the predicted probability of delinquency. Because the basic credit-rating principles assume that certain types of households are more likely to repay than others, a model controlling for household’s ability to borrow was also estimated. Whether significant or not, all of the coefficients for the variables have the expected signs.

All five different sources of adverse shock investigated significantly increase the probability of arrears on consumer debt. Households whose finances do not meet expectations, or who encounter random negative events (e.g. death, illness or divorce), and those who face increased demands on available resources (e.g. due to increased dependency) are likely to respond by falling behind on or suspending their repayments. The marginal effects suggest that for an indebted household who experienced a random negative event, the probability of falling behind or abandoning repayments increased by 5%, and 6% in the case of expenditure shock; or 4 percentage points in the case of family increase and 5 percentage points for subjective financial worries. The individual relationships between the proxies for negative shock and delinquency do not change even when controlling for the ability to borrow proxies: which may suggest that, at the risk of negative shock, current resources might not be enough to predict future repayment performance.

The practicalities of these relationships are not really complex if one considers the fact that negative economic shocks not only erode the value of precautionary wealth but are also associated with additional financial burdens. For instance, a person who is unable to work through injury may not only have to contend with negative income but also extra medical bills. Hence, debt repayment performance will be highly influenced by either one or both of these outcomes. Moreover, shocks are likely to be invisible to lenders at the time a credit request is granted, making it harder to gauge repayment performance with certainty. Then there are ‘financial worries’ that impinge on overall well-being. If families are suddenly dissatisfied with their financial situations, they will exercise greater caution when handling available finances and they will attempt to mitigate further uncertainty and seek to prioritise resources. Ultimately, suspending consumer debt payment might be the only rational option at the disposal of such families.

Obviously, households for whom incomes fail to meet expectations or for whom budgetary pressures suddenly become unbearable might attempt to acquire new debt in order to plug their deficits, but given their falling credit ratings they are likely to find this route closed to them. This suggests that in the absence of direct relief, debt problems might be binding.

The expenses-to-income ratio was only statistically significant at the lower end of the distribution (quintile 2) suggesting a 5 percentage point decrease in the probability of delinquency. A similar pattern holds when controlling for household ability to borrow. No significant relationship is observed at the upper end of the distribution of the expenses-to-income ratio. A possible explanation for this kind of interaction may be that high expenditure is only indicative of the household’s accessibility to goods and services, itself influenced by the household’s ability to pay for them (i.e. solvency) rather than a delinquency risk. Notwithstanding this explanation, these findings show no compelling evidence to suggest that excessive spending is related to consumer debt delinquency.

The three covariates of ‘ability to borrow’ did not have a discernible effect on the relationships observed earlier, which is not surprising given that lenders are able to observe these characteristics when deliberating on credit applications, and because household economic status can change after a credit request has been granted (including erosion of precautionary wealth) it is the economic performance at the time of maturity that matters for repayment performance. For these, only homeownership was significant; but this is a very weak indicator of wealth in the South African context given the government’s Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) policy.

In a nutshell, the evidence suggests that income shocks and other trigger events which increase strains on the family resources are more important in explaining consumer debt repayment difficulties among the sample population than excessive spending, and this evidence supports fully the hypotheses formulated. Overall, it is then sensible to infer that, assuming lenders adhere to strict underwriting standards, households will be able to sustain heavier expenditure burdens without abandoning their obligations unless they suffer adverse alterations in their economic circumstances. It is plausible, however, to acknowledge that excessive spending might render some households more sensitive to trigger events, especially if these households are treading on the edge and borrowing on top of huge outstanding bills. Such consumers might abandon their obligations quicker than average consumers who borrow sparingly and maintain some modest savings. This offers an interesting problem for future research.

While studies like these often invoke questions of generalisability and transferability owing to the jurisdiction-specific aspect of the data, the confidence in the implications and policy recommendations provided here relies, inter alia, on the following considerations. First, the CAPS collects data from a diverse population: from rural to peri-urban to urban, from squatter camps to townships to affluent suburbs. This is clearly representative of the population make-up of contemporary South Africa. Second, the study is guided by hypotheses derived from theoretical and empirical considerations of consumer debt use, but one which is also sceptical of cultural considerations in analysing debt behaviours of a population. Note that the cultural perspective will attempt to portray variations in consumption behaviours as simply a function of ‘cultural’ differences ‒ albeit without compelling evidence, but simply to argue that a certain cohort of consumers is unique. Surely, shocks to income or unreasonable use of financial instruments cannot be uniquely South African or ‘Capetonian’ for that matter.

4. Conclusion and implications

This analysis used the CAPS data to investigate whether South African households are more likely to be delinquent on their consumer debts as a result of shocks that negatively affect their economic circumstances or as a result of excessive expenditure that renders households financially overstretched. The logistic regression analyses indicate that households are more likely to experience debt repayment difficulties if they suffer from negative income shocks and other circumstances that alter their financial circumstances. There was insufficient evidence to relate arrears to the excessive spending ‒ even when controlling for the fact that some households are more likely to repay than others. Two major inferences can be deduced from this: first, insofar as lenders evaluate risk, consumers will most likely take on amounts they are able and willing to repay, such that excessive spending is less likely to be a major factor in the repayment performance for the majority of credit-active households. While this might seem like a romantic view of consumer credit decision-making, it is sensible to note that most lenders will have an intrinsic profit motive and an aversion to loss, so they will have no incentive to see households borrowing more than they can comfortably repay. As such, the concept of ‘reckless lending’ becomes less compelling. Future research efforts need to consider the extent to which consumers’ hidden characteristics (in their desperation to smooth consumption) drive adverse selection problems.

Second, even when households borrow within their means they are likely to struggle with repayments if they should experience post-consumption (especially unanticipated) disruptions in their income streams. The implications for credit underwriting here are that, while the hitherto traditional credit risk-evaluation procedures might reduce the preponderance of arrear on consumer debt, their inability to account for the likelihood of such interruptions means that consumer debt problems cannot be completely eliminated. Credit underwriters would do well to incorporate situational factors in their credit risk models. Predictive models should incorporate as many variables that measure sensitivity to shock as possible. Factors such as local economic conditions, dependency levels or type and level of insurance, inter alia, should provide some information on the level of risk exposure.

Overall, it is unlikely that consumers will divulge enough information to warn lenders of the potential risk of adverse changes in their incomes during a particular credit life. Hence, it makes sense to accept, firstly, that consumer debt delinquency (or over-indebtedness) is an inevitable feature of the credit system and, secondly, that living in a perpetual state of over-indebtedness is not only a well-spring of intergenerational impoverishment on households but also stifles overall economic growth. Thus far, the implications for consumer credit regulation are clear.

In a context like South Africa where idiosyncratic shocks are widespread, often have longer lasting adverse consequences, yet financial buffering to mitigate these consequences is either inadequate at best or non-existent at worst, tighter regulations on credit granting cannot be enough to address consumer debt problems. Post-contractual regulatory interventions with tightly regulated measures for relief and rehabilitation of consumers’ indebtedness are as important, if not more so. Such measures should be adequately regulated so they are able to release unfortunate debtors from perpetual indebtedness as well as aid those who might still have the capacity to repay. In the current form, the debt restructuring provisions of the NCA are only meaningful to those who still have the capacity to repay. Furthermore, regulatory and educational efforts should also give due consideration to improving channels for self-insurance and employer non-discretionary insurance (e.g. unemployment and medical insurance savings, and severance payments).

Finally, a caveat is in order: since the CAPS survey is not a typical survey of consumer finances and did not collect enough information on household income and expenditure, the conclusions drawn should not be taken with absolute certitude, but as a springboard for further investigation. Nonetheless, the data aptly satisfied the objectives of this study.

Acknowledgements

This is a revised version of Chapter Five of the author’s PhD thesis ‘The Dynamics of Consumer Credit and Household Indebtedness in South Africa’ submitted in November 2014 to the Doctoral Degree Board of the University of Cape Town. Greater detail on the study may be found in Ssebagala (2015). The author’s thesis was completed under the direction of Professor Jeremy Seekings (Department of Sociology, University of Cape Town). The author is grateful to Professor Jeremy Seekings, Professor Nicoli Nattrass, Professor David Lincoln, the participants of the CSSR weekly seminars and the anonymous referees for their comments and guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCiD

Ralph A Ssebagala http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8200-5910

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Available online: http://ncr.org.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=42 Accessed 20 September 2014.

2 The alternative theory (often used in reference to housing debt) is the ‘Equity theory’, which postulates that rational borrowers compare the financial costs and returns of their mortgage positions in deciding whether to continue or terminate mortgage payments.

References

- Alfaro, R, Gallardo, N & Stein, R, 2010. The determinants of household debt default. Documentos de Trabajo Banco Central de Chile no. 574. Santiago.

- Avery, RB, Calem, PS & Canner, GB, 2004. Consumer credit scoring: Do situational circumstances matter? Journal of Banking & Finance 28(4), 835–856. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4266(03)00202-4

- Bachmann, R, Berg, TO & Sims, ER, 2015. Inflation expectations and readiness to spend: Cross-sectional evidence. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7(1), 1–35.

- Bertrand, M, Karlan, D, Mullainathan, S, Shafir, E & Zinman, J, 2010. What’s advertising content worth? Evidence from a consumer credit marketing field experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(1), 263–305. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2010.125.1.263

- Bikker, JA & Metzemakers, PA, 2005. Bank provisioning behaviour and procyclicality. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 15(2), 141–157. doi: 10.1016/j.intfin.2004.03.004

- Chatterjee, S, Corbae, D, Nakajima, M & Ríos-Rull, JV, 2007. A quantitative theory of unsecured consumer credit with risk of default. Econometrica 75(6), 1525–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0262.2007.00806.x

- Collins, DL & Leibbrandt, M, 2007. The financial impact of HIV/AIDS on poor households in South Africa. AIDS (London, England) 21(Suppl 7), S75–81. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300538.28096.1c

- Disney, R, Bridges, S & Gathergood, J, 2008. Drivers of over-indebtedness. Centre for Policy Evaluation, University of Nottingham, Nottingham.

- DTI (Department of Trade and Industry), 2004. Consumer credit law reform: Policy framework for consumer credit. Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria.

- Duygan-Bump, B & Grant, C, 2009. Household debt repayment behaviour: What role do institutions play? Economic Policy 24(57), 107–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0327.2009.00215.x

- Evans, M, Hastings, N & Peacock, B, 2000. Statistical distributions. 3rd edn. Wiley, New York.

- Farinha, L & Lacerda, A, 2010. Household credit delinquency: Does the borrowers’ indebtedness profile play a role? Financial Stability Report, Part 2 (November 2010):135–153.

- Gathergood, J, 2012. Self-control, financial literacy and consumer over-indebtedness. Journal of Economic Psychology 33(3), 590–602. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2011.11.006

- Getter, DE, 2003. Contributing to the delinquency of borrowers. Journal of Consumer Affairs 37(1), 86–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2003.tb00441.x

- Grant, C, 2010. Shocks and the debt repayment behaviour of households in the EU. http://www.southampton.ac.uk/~mkwiek/WIEM2010/Grant-ProbitFE.pd Accessed 4 April 2012.

- Greene, WH, 1998. Sample selection in credit-scoring models. Japan and the World Economy 10, 299–316. doi: 10.1016/S0922-1425(98)00030-9

- Gross, DB & Souleles, NS, 2002. An empirical analysis of personal bankruptcy and delinquency. Review of Financial Studies 15(1), 319–347. doi: 10.1093/rfs/15.1.319

- Haushofer, J & Fehr, E, 2014. On the psychology of poverty. Science 344(6186), 862–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1232491

- Heidhues, P & Kőszegi, B, 2010. Exploiting naivete about self-control in the credit market. The American Economic Review 100(5), 2279–2303. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.5.2279

- Hill, RP & Kozup, JC, 2007. Consumer experiences with predatory lending practices. Journal of Consumer Affairs 41(1), 29–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00067.x

- Himmelstein, D, Warren, E, Thorne, D & Wollhandler, S, 2005. Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy. Health Affairs W5, 63–73.

- Ho, G & Pennington-Cross, A, 2006. The impact of local predatory lending laws on the flow of subprime credit. Journal of Urban Economics 60(2), 210–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2006.02.005

- Hurwitz, I & Luiz, J, 2007. Urban working class credit usage and over-indebtedness in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 33(1), 107–131. doi: 10.1080/03057070601136616

- James, D, 2012. Money-go-round: Personal economies of wealth, aspiration and indebtedness. Africa 82(01), 20–40. doi: 10.1017/S0001972011000714

- Jappelli, T, Pagano, M & Di Maggio, M, 2008. Households’ indebtedness and financial fragility. Journal of Financial Management Markets and Institutions 1(1), 23–46.

- Jentzsch, N & Riestra, ASJ, 2006. Consumer credit markets in the United States and Europe. In Bertola, G, Disney, R & Grant, C (Eds.), The economics of consumer credit. MIT Press, Cambridge and London, pp. 27–62.

- Katona, G, 1960. The powerful consumer: Psychological studies of the American economy. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Kennedy, K, Delany, SJ & Mac Namee, B, 2011. A framework for generating data to simulate application scoring. Credit Scoring and Credit Control XII, Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Management School.

- Knight, L, Roberts, BJ, Aber, JL & Richter, L, 2015. Household shocks and coping strategies in rural and peri-urban South Africa: Baseline data from the size study in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of International Development 27(2), 213–233. doi: 10.1002/jid.2993

- Lam, D, Ardington, C, Branson, N, Case, A, Leibbrandt, M, Menendez, A, Seekings, J & Sparks, M, 2008. The cape area panel study: A very short introduction to the integrated waves 1-2-3-4 data. University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Lopes, P, 2008. Credit card debt and default over the life cycle. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 40(4), 769–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00135.x

- Meier, S & Sprenger, C, 2007. Impatience and credit behavior: Evidence from a field experiment (No. 07-3). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

- Pesola, J, 2011. Joint effect of financial fragility and macroeconomic shocks on bank loan losses: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Banking & Finance 35(11), 3134–3144. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.04.013

- Peter, V & Peter, R, 2006. Risk management model: An empirical assessment of the risk of default. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics 1, 42–56.

- Roos, MWM, 2008. Willingness to consume and ability to consume. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 66(2), 387–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2006.03.008

- Saunders, P, 2011. Down and out: Poverty and exclusion in Australia. Policy Press, Bristol.

- Saunders, P & Hill, T, 2008. A consistent poverty approach to assessing the sensitivity of income poverty measures and trends. Australian Economic Review 41(4), 371–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8462.2008.00521.x

- Seekings, J & Nattrass, N, 2008. Beyond ‘fluidity’: Kinship and households as social projects. Centre for Social Science Research, Cape Town.

- Ssebagala, RA, 2015. The dynamics of consumer credit and household indebtedness in South Africa. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town.

- Stoop, PN, 2009. South African consumer credit policy: Measures indirectly aimed at preventing consumer over-indebtedness. Mercantile Law Journal 21, 365–386.

- Townley-Jones, M, Griffiths, M & Bryant, M, 2008. Chronic consumer debtors: The need for specific intervention. International Journal of Consumer Studies 32, 204–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2008.00666.x

- Van Apeldoorn, JC, 2008. The ‘fresh start’ for individual debtors: Social, moral and practical issues. International Insolvency Review 17(1), 57–72. doi: 10.1002/iir.156

- Viimsalu, S, 2010. The over-indebtedness regulatory system in the light of the changing economic landscape. Juridica International XVII, 217–226.

- Whitley, J, Windram, R & Cox, P, 2004. An empirical model of household arrears. Bank of England Working Paper no. 214. London.

- Zhu, N, 2011. Household consumption and personal bankruptcy. The Journal of Legal Studies 40(1), 1–37. doi: 10.1086/649033

- Zhu, LY & Meeks, CB, 1994. Effects of low income families’ ability and willingness to use consumer credit on subsequent outstanding credit balances. Journal of Consumer Affairs 28(2), 403–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.1994.tb00859.x