ABSTRACT

Most studies of the tourism–development nexus in developing countries tend to focus on short-term and monetary tourism effects, while understating non-monetary and longer-term effects of tourism on local and regional development. Although less tangible and weakly understood, non-monetary and/or long-term tourism effects can both reinforce and undermine short-term and monetary tourism effects. This article analyses how tourism stimulates local entrepreneurship and small enterprise development, and to what extent these small enterprises fuel non-monetary aspects of regional development. Evidence from career pathways of different types of local entrepreneurs in western Uganda suggests that tourism can enlarge peoples’ capabilities, awareness and assets to control their own well-being. This study indicates that tourism can act as a catalyst for small enterprise development in the local economy without inducing major skills’ leakages.

1. Introduction

Tourism can be considered a tool for local and regional development in peripheral areas of developing countries when local labour, products and services of small, medium and micro-enterprises (SMMEs) are linked to the tourism value chain (Nyaupane & Poudel, Citation2011; Mitchell, Citation2012; Anderson & Juma, Citation2014). Because small tourism enterprises are unable to create a market themselves, they have to tap into an existing value chain (Ashley, Citation2007). The ability of small enterprises to link to the tourism value chain depends on a number of tourism-related and non-tourism-related factorsFootnote1 (Wall & Mathieson, Citation2006).

In this regard, the importance of SMMEs and their effect on regional development has been widely acknowledged in the literature (e.g. Thomas et al., Citation2011; Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012; Koens & Thomas, Citation2015). Despite the fact that tourism can contribute to multiple dimensions of regional development by acting as a catalyst for local empowerment, networks, knowledge and skills development (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2016), most tourism impact studies tend to focus on short-term and monetary tourism effects. Nevertheless, the importance of non-monetary and/or longer-term effects should not be underestimated, because they can both reinforce and undermine the development of the destination and beyond (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010; Scheyvens, Citation2011; Adiyia et al., Citation2016). To address this issue, Mitchell & Ashley (Citation2010) developed a value chain-based modelFootnote2 that takes dynamic tourism effects on the local economy into account, such as ‘the upgrading of skills in the local labour market’ (Mitchell, Citation2012:462). In the model, stimulating local entrepreneurship and developing small enterprises are considered vital in maximising the regional development potential of tourism. Small enterprises in tourism can provide a key factor in sustaining livelihoods of the poor, not only by generating financial resources for further investments but also by developing both tourism-specific skills and general skills in the households’ productive capacity (Kirsten & Rogerson, Citation2002; Snyman & Spenceley, Citation2012). The transfer of these skills can spread to other economic sectors and areas, inside and outside the destination, and is hence crucial for the regional development potential of tourism (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010; Truong et al., Citation2014).

Yet several scholars claim that the different mechanisms through which tourism can stimulate small enterprise development inside and outside the tourism sector are under-researched in developing contexts (Scheyvens & Russell, Citation2012; Koens & Thomas, Citation2015). In addition, recent studies have identified non-financial and context-dependent barriers for local entrepreneurs to enter the tourism value chain in the developing world (Kokkranikal & Morrison, Citation2011; Skokic & Morrison, Citation2011; Anderson & Juma, Citation2014; Truong et al., Citation2014). Therefore, several studies plead for the analysis of career pathways of local entrepreneurs to clarify how tourism stimulates regional development in a non-monetary way (Beeka & Rimmington, Citation2011; Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012).

This article aims at contributing to the current understandings of this existing research gap. The area around Kibale National Park (KNP) in western Uganda was selected as a case study, because Uganda is an emerging destination in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) for which the government promotes tourism as a strategy to develop peripheral regions. Accordingly, the research aims of this article are as follows:

to analyse how tourism stimulates local entrepreneurship and small enterprise development; and

to assess to what extent these small enterprises fuel non-monetary aspects of regional development

2. Modelling small enterprise performance

In developing countries, the development potential of tourism has been widely acknowledged because the sector generally aims at balancing existent regional disparities and creates benefits for the socio-economic development of regions and communities (Scheyvens, Citation2007; Kauppila et al., Citation2009; Saarinen & Rogerson, Citation2014). In this regard, the importance of small enterprises is based on two grounds. First, it is argued that small enterprises have a larger impact on regional development due to their numerical importance, labour-intensive and flexible character, predominant local ownership and integration in the local economy (Vanneste & Ryckaert, Citation2011; Medina-Muñoz et al., Citation2016). Second, small ‘survivalist’ enterprises contribute to regional development by facilitating the livelihoods of the rural poor as an economic necessity, while small ‘expansionist’ enterprises facilitate the escape from poverty as an economic choice (Ellis, Citation1999). Tourism can increase small enterprise performance by improving the efficiency and lifespan of survivalist enterprises, potentially pushing them to become expansionist. Expansionist enterprises in turn can increase the competitiveness of the tourism destination and stimulate the local economy by providing standards for (improved) local products and services.

In the quest for defining small enterprise performance in a developing context, perspectives have dominantly focused on establishing new businesses and characterising entrepreneurial motivation (Ateljevic & Doorne, Citation2000). Based on entrepreneurial motivations, a distinction is generally made between ‘push’ and ‘pull’ entrepreneurs, in which the former type is pushed out of their previous activity due to necessity, while the latter is pulled out of their previous activity due to an opportunity (Dawson & Henley, Citation2012). In tourism, some motivations exceed pure economic motives, resulting in so-called ‘lifestyle’ entrepreneurship. However, pure lifestyle entrepreneurship rarely occurs in livelihood-based survival economies of developing countries (e.g. Beeka & Rimmington, Citation2011; Skokic & Morrison, Citation2011; Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012). Nevertheless, a recent study by Beeka & Rimmington (Citation2011) with Nigerian entrepreneurs found that lifestyle motives and economic motives are not strict distinctive categories in developing contexts. In addition, the outcome of small business development on regional development varies among regions in SSA, and the extent to which small enterprises are of benefit is contested (Koens & Thomas, Citation2015). For example, Koens & Thomas (Citation2015) found that successful small business owners tend to prefer to leave townships in Cape Town due to weak sense of place. This further triggers the need for research on local entrepreneurship and its link with tourism and regional development in developing countries.

Therefore, we developed a model concerning different types of business performance factors in order to analyse small enterprise performance, while dividing these factors into an internal sphere and an external sphere (). As shown in , the internal sphere can be subdivided into performance factors related to the entrepreneur, such as skills, experience and the socio-economic background of the entrepreneur, and performance factors related to the business itself, such as resources, strategies and the business format (Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012). The external sphere also comprises two interlinked subgroups: support variables offered by government and private entities, and the business environment that entails the physical environment of the enterprise’s location (Lerner & Haber, Citation2001; Morrison & Teixeira, Citation2004; Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012).

3. Methodology

3.1. Study area

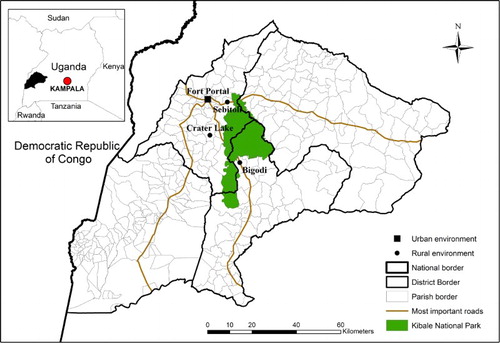

This article focuses on the surroundings of KNP in western Uganda (). KNP was upgraded from Forest Reserve to National Park in 1993, and is well known for the largest population of chimpanzees in East Africa (Adiyia et al., Citation2014). KNP provides interesting characteristics to study non-monetary and longer-term tourist effects on local entrepreneurship and small enterprise development because it is a popular halt in tourism itineraries and attracts domestic and international tourists without being a top destination, in a national park setting with natural and cultural assets that can be found in many SSA countries. Moreover, the area comprises a set of ‘business environments’Footnote3 with a mainstream placement in the tourism value chain. This enables one to study the impact of the external sphere on small enterprise performance, and to understand possible barriers for local entrepreneurs to enter the value chain.

3.2. Research methods

Information was collected from 71 qualitative ‘life-history’ interviews with different types of local entrepreneurs in western Uganda (). Life-story interviewing is ‘a qualitative research method for gathering information on the subjective essence of one person’s entire life that is transferable across disciplines’ (Atkinson, Citation1998:123). Previous tourism studies successfully used this narrative approach to analyse business success factors and constraints among entrepreneurs in Sweden (Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012), and to assess the effect of opportunity identification and development from Nigerian entrepreneurs on their career choices (Beeka & Rimmington, Citation2011). Similar to these studies, a timeline was used in our interview protocol to integrate respondents’ past and present experiences as local entrepreneurs (Beeka & Rimmington, Citation2011; Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012). Internal consistency of the story was used as a control mechanism to ensure the narrative validity and to remedy the risk of a highly subjective story based on a mixture of facts and fiction (Atkinson, Citation1998; Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012:653). Because it was not possible to follow entrepreneurs through different points in time (i.e. a longitudinal approachFootnote4), this study also interviewed entrepreneurs concerning future plans to shift between sectors and to move their business location wise. summarises the topics covered during the interviews.

Table 1. Main themes and topics covered in semi-structured interviews.

Respondents were selected by snowball sampling, starting from key stakeholders who were contacted via established tourism companies that were not included in the sample. We aimed to collect a representative sample by following a purposive samplingFootnote5 strategy, taking different primary activities and different business environments into account (Appendix A, ). In this regard, primary activity is defined by the respondents themselves, and can relate to their main source of income or to their core interest. Accordingly, the respondents’ categories A to E contain different typesFootnote6 of local entrepreneurs (). In a first step, the authors listed all businesses in different business environments embedded in the study area by sketching a map to gather insight in the number and type of entrepreneurial activities. Accordingly, we strived for a purposive sample that reflects the ratio of local entrepreneurs in the different business environments of the study area. To cross-check, structure and clarify information from local entrepreneurs, expert interviews were conducted with local (category F) and foreign (category G) tour operators, tourism organisations, researchers and representatives of the government who have built expertise on tourism matters. All interviews were transcribed and coded using NVivo ® 10 to identify themes. The duration of the interviews varied between 30 and 90 minutes.

Table 2. Categories of respondents.

Although the number of life-story interviews is too small to analyse results statistically, too much information would be lost in a pure qualitative analysis. Therefore, in the margins of qualitative data gathering, some quantitative numbers are used in the Results section to depict certain tendencies in an illustrative manner and to facilitate the interpretation of qualitative results. Additional information was gathered by critically reviewing policy documents, evaluation reports and statistical data from international and national tourism institutions, and from informal discussions with local entrepreneurs in order to triangulate results.

4. Results

Based on previous literature, we distinguished three different stages towards entrepreneurship during which skills can be developed: the education stage (students); the employment stage (employees); and the entrepreneurial stage (business owners). Note that each stage can be situated in tourism and beyond tourism, and that movements from one stage to another can be reversible, temporary and complementary.Footnote7 The education stage in tourism is related to different entities on different levels, ranging from universities to local tourism institutes. In total, 21 respondents (42%) studied tourism and obtained a specific tourism degree. Interview analysis shows that personal interests ‘pulls’ and the low cost of tourism education respectively ‘pushes’ respondents to engage in higher tourism education and tourism employment. In these two phases, financial necessity plays an important role as a push factor, while respondents are generally pulled to entrepreneurship by perceived financial opportunities. Being self-employed is highly valued due to negative perceptions of being an employee and due to perceived benefits of being self-employed. The majority of respondents want to stay in the tourism sector, preferably as entrepreneurs. However, if tourism does not fulfil their expectations or stops growing, the entrepreneurs argue that they will look for other activities or start enterprises in other sectors:

At that time it was the cheapest option. Because … the school fees was 150.000 [Uganda Shilling] for 3 months and you get a certificate. You see, how cheap it was. Everyone could afford that. (Category A.46)

I love tourism. But would I sit and see how it’s elapsing? No, I would shift to any other business. (Category C.26)

4.1. Impacting the external sphere

Local entrepreneurs in western Uganda confirm the existence of severe barriers for SMMEs to enter the tourism value chain, such as the lack of information, understanding market requirements, access to finance, credibility and reputation, and a critical size. The claim of tourism entrepreneurship requiring low capital (Rogerson, Citation2008b; Vanneste & Ryckaert, Citation2011) has been contested strongly by the respondents. Moreover, they confirm the assumption that seasonal sectors hamper competitive participation of SMMEs because seasonality fuels financial and strategic vulnerability:

I never had clients like I expected at first. [ … ] Because I thought: ‘Ah, people will come and I can take them for tours’, but it was not like that. I would say that marketing and reaching the clients was not an easy thing. (Category B.15)

Yes, they see tourists roaming around. So they say: ‘Why don’t I open a restaurant so that these tourists can have food?’ You see, they are seeing them, they are being exposed. So they have seen the other neighbor … people are going there taking fruits, so you say: ‘I will also have fruits. Let me open a store.’ You see? So it’s really about numbers, it’s about exposure … (Category F.34)

But there are bigger opportunities in Fort Portal as opposed to Bigodi, because … it has limited attraction. [ … ] They are limited in terms or permits in a year [in KNP]. (Category F.30)

I think mainly a certain type of tourists is going in those areas. Because they have some upmarket lodges in that area: there’s Ndali lodge. And the visitors hardly get out of their vehicles and they simply go to the lodge. And they don’t move around much. So there is very little contact with the local people around some of the lodges. (Category F.64)

Initially someone came in and mobilized us to teach us about crafts and what what. So we made baskets. But at the end of the day, we have no tourists to sell them. So why make something that is not going to sell. (Category F-FP-03)

4.2. Impacting the internal sphere

Results concerning the internal performance factors for entrepreneurial success are presented in Appendix A, . A first group of factors corresponds with entrepreneurial characteristics, comprising attitudes, experience and skills. Skills are the most frequently mentioned internal performance factor (n = 46), underlining the relevance of skills development in the tourism–development nexus. This was confirmed by several expert interviews. A second group of internal performance factors relates to the enterprise itself, and comprises having financial capital, a large social network and adequate human resources. Respondents stress that these factors generally intertwine with skills and attitudes. Local entrepreneurs were also questioned about which skills they developed or improved during different stages leading to entrepreneurship. These results are presented in Appendix A, and show a high recurrence of generic skills compared with vocational skills, suggesting that tourism stimulates transferrable skills in the local economy. Respondents confirmed the transferability of skills from their own enterprises to other economic activities:

Yes, the skills I’ve learned in tourism are properly helping me with my shop because with customer care you have to care the customer first, or to look after the customer, to welcome the customer well. (Category E-FP-16)

The quality of the tourism training institutes is very poor. They don’t have the resources to expose their students to that what is maybe trained in their curriculum. [ … ] They wouldn’t have the experience or exposure to meet that or to be able to implement because they have no reference point. [ … ] The students cannot implement what they learned theoretically because they do not see it. (Category G-00-12)

Tourism has opportunities, especially for beginners. It’s a good place to start. You can get into other things. Because you know from tourism, I can do a lot of different businesses. I can easily go and do a PR manager for a brand like MTN. [ … ] People start from here and move to other things. (Category F-KA-29)

Assuming that respondents will follow the intended spatial movements, it is clear that the spatial distribution of transferable skills contributes to human capital as a non-monetary dimension of regional development inside the study area. However, results also show that the movement of skills is dependent on external enterprise performance factors, stressing the prerequisite to link to the existing tourism value chain in order to fuel local entrepreneurship and regional development. Hence, results confirm previous findings which argue that the regional development potential of tourism crucially hinges upon linkage opportunities between the tourism value chain and local entrepreneurs (e.g. Kirsten & Rogerson, Citation2002; Meyer, Citation2009; Rogerson, Citation2012, Citation2014).

5. Discussion

Analysis of the external sphere shows that several factors create barriers for local entrepreneurs to enter the tourism value chain. The majority of these barriers relate to the absence of a market as a result of a complex set of factors. Several of these external support variables are governed on the national level, such as limited marketing efforts, lack of diversified product development and lack of accessibility to the tourism attractions because of limited road infrastructure (Adiyia et al., Citation2015). The limited annual budget allocated for tourism marketing constrains an innovative product development, the diversification of tourist activities at existing attractions and the creation of new attractions which potentially involve more local entrepreneurs. Furthermore, many expert interviewees stress the poor state of the national road infrastructure and the necessity to open up inaccessible places that might become attractive for investors. Entrepreneurs suggest that the government could improve regional business environments, and hence catalyse SMME development, by providing simple infrastructure and investing in the habituation of chimpanzees at the northern park entrance. Weaknesses in the external sphere are intertwined with national planning policies related to infrastructure development, tourism marketing and product development, showing an inherent problem that challenges the feasibility of regional development aims in current policy discourses in SSA.

Our findings support Christian (Citation2012) and Carlisle et al. (Citation2013), who state that national policy should focus on overcoming existing barriers for local entrepreneurs to enter the value chain. Therefore, tourism should be further prioritised on the national political agenda in terms of: increasing financial resources to support marketing efforts and infrastructure development; building capacity to invest in high-quality local and national tourism institutions using a field-based approach that includes highly valued transferable skills; and developing stable external governance partnerships with the private sector to align the education and training system with the requirements of the transforming tourism industry (Scheyvens, Citation2009; Carlisle et al., Citation2013; Adiyia et al., Citation2015). The focus should be on incorporating small survivalist enterprises in these government-supported training programmes, because previous studies indicated that these enterprises struggle most with access to finance and training programmes (e.g. McGrath, Citation2005; Rogerson, Citation2008a, Citation2008b). In this regard, expansionist enterprises could share their experience in vocational training programmes that ‘enhance the management skills and tourism knowledge of those who are interested in establishing a tourism business’ (Zhao et al., Citation2011:1588). However, examples of governmental support interventions have been rare in SSA, where ‘the core issue for tourism policy has been that of expanding the size of tourism economies rather than major concerns about the actual beneficiaries of tourism development’ (Rogerson, Citation2014:118).

Analysis of the internal sphere underlines the importance of transferrable skills and entrepreneurial motivations in different stages towards entrepreneurship, and provides new information on how tourism can act as a starting point to fuel non-monetary aspects of regional development in peripheral regions with limited alternative growth options. While respondents are often pushed towards tourism studies and employment due to financial necessity, respondents are more strongly pulled to tourism entrepreneurship because of perceived financial opportunities. In other words, tourism stimulates local entrepreneurship in the sense that it is the most desirable way for locals to participate in the tourism value chain. Therefore, withdrawing from the tourism sector as an entrepreneur is mainly due to external barriers that hinder connections with the value chain.

Furthermore, analysis shows that several non-monetary internal performance benefits such as product knowledge, integration into networks and marketing opportunities are transferrable to non-tourism sectors. depicts the transfer of these non-monetary benefits (black arrows) in possible pathways to (tourism) entrepreneurship. From our research, we learnt that enrolment in tourism studies is considered rather inexpensive, and that skills acquired in tourism are transferrable to sectors in the local economy beyond tourism. This means that tourism can be considered an ‘affordable’ starting point to fuel regional development. Therefore, our study indicates that tourism can act as a catalyst for small enterprise development in many economic sectors without inducing major skills’ leakages.

Finally, our findings should be interpreted in the light of various studies which argue that tourism employment generates low incomes in SSA (e.g. Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010; Gartner & Cukier, Citation2012; Adiyia et al., Citation2014). This study shows that experience in tourism employment plays a key role in creating local linkages with the value chain in which non-monetary assets such as product knowledge and a social network are crucial, highlighting that ‘benefits of tourism employment exceed “jobs and income” by providing human and social capital required for rural poor to empower themselves and successfully start-up and manage alternative off-farm activities that can lead them out of extreme poverty’ (Adiyia et al., Citation2016; n.p.). Accordingly, our findings strongly suggest that tourism can facilitate peoples’ capabilities and assets, while empowering local entrepreneurs to have greater control over their own well-being.

6. Concluding remarks

This study aimed at understanding how tourism stimulates local entrepreneurship and SMME development, and how local entrepreneurship can contribute to regional development in a non-monetary way. Using life-story interviews to analyse career pathways of entrepreneurs in western Uganda, internal and external performance factors were analysed to explain SMME development and small enterprise performance.

Results on external factors confirm most assumptions in the literature advocating for investments in the tourism sector that can lead to a better accessibility, a legislative framework, innovative product development and an investment-friendly climate for local entrepreneurs to tap into the tourism value chain. In contrast, evidence on internal factors provides new information on how tourism can act as a starting point to fuel regional development beyond easily measurable quantitative indicators, such as income distributions, number of international visitor arrivals or foreign exchange earnings. Evidence from career pathways of local entrepreneurs suggest that tourism can provide an impetus for training, gaining product knowledge, networking and market opportunities, accumulation of experience and skills development, while enlarging peoples’ capabilities, awareness and assets to control their own well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Tourism-related factors comprise the type of tourism development of the site, the entrepreneurial capacity of local entrepreneurs to meet the tourism demand directly or indirectly by supplying other tourism businesses, and the historical development of tourism on different scales. Non-tourism-related factors embed the stage of local economic development, the structure of the local economy and the presence of entrepreneurial skills, which influence the business environment and hence small enterprise participation (Wall & Mathieson, Citation2006).

2 The conceptual model ‘follows the tourism dollar through the tourism value chain’ in three pathways by which tourism benefits and costs can be transmitted to a specific target group – that is, the poor – via direct, indirect and dynamic effects (Mitchell, Citation2012; Mitchell et al., Citation2015). Dynamic effects include long-term changes in the local economy and patterns of growth, such as increasing entrepreneurial motivations and skills development, or the erosion of natural assets due to tourism (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010; Mitchell, Citation2012; Mitchell et al., Citation2015). The details of this model are discussed in several recent articles, and will hence not be explained in this article. For further details, we refer to the primary source of the model (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010).

3 Tourism activities around KNP are organised in different settings, shaped by cultural, socio-economic, physical and political characteristics (Adiyia et al., Citation2014). Because small business performance is partly shaped by its business environment (), KNP is an interesting case to understand different types of interactions between the external sphere and small business performance.

4 Future research could track entrepreneurs through different points in time to evaluate the ratio of skill leakages, and assess the impact of entrepreneurs that left the destination on the social structures of the area.

5 Purposive sampling is based on the assumption that certain categories of individuals may have a unique or important perspective on the phenomenon in question (Robinson, Citation2014).

6 Any typology of individuals that is based on a limited set of criteria is not able to encompass the complexity of the organisation and decision-making of those individuals (Thomas et al., Citation2011). The different categories in this study are used as a descriptive tool to better understand entrepreneurial dynamics using different perspectives. Accordingly, the authors are able to determine essential aspects and recognise variations of the experience as a kind of triangulation (Polkinghorne, Citation2005:140). The authors chose ‘primary activity’ as a measure to discriminate entrepreneurs to examine local entrepreneurship beyond the narrowly defined tourism sector.

7 An individual can be simultaneously at different stages. For example, category E entrepreneurs are employed in tourism, while having a small business beyond tourism. In addition, career paths of entrepreneurs can be non-linear, implying that individuals in the employment or entrepreneurial stage can still follow different types of educational courses to strengthen their knowledge and enhance their human capital base. Therefore, movements between stages can be reversible and/or temporary.

References

- Adiyia, B, Vanneste, D, Van Rompaey, A & Ahebwa, WM, 2014. Spatial analysis of tourism income distribution in the accommodation sector in western Uganda. Tourism and Hospitality Research 14(1-2), 8–26. doi: 10.1177/1467358414529434

- Adiyia, B, Stoffelen, A, Jennes, B, Vanneste, D & Ahebwa, WM, 2015. Analysing governance in tourism value chains to reshape the tourist bubble in developing countries: The case of cultural tourism in Uganda. Journal of Ecotourism 1–17. doi:10.1080/14724049.2015.1027211

- Adiyia, B, Vanneste, D & Van Rompaey, A, 2016. The poverty alleviation potential of tourism employment as an off-farm activity on the local livelihoods surrounding Kibale National Park, western Uganda. Tourism and Hospitality Research doi:10.1177/1467358416634156

- Anderson, W & Juma, S, 2014. Linkages at tourism destinations: Challenges in Zanzibar. ARA Journal of Tourism Research 3(1), 27–41.

- Ashley, C, 2007. Pro-poor analysis of the Rwandan tourism value chain. An emerging picture and some strategic approaches for enhancing poverty impacts (Vol. 44). Overseas Development Institute, London.

- Ateljevic, I & Doorne, S, 2000. ‘Staying within the fence’: Lifestyle entrepreneurship in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 8(5), 378–92. doi: 10.1080/09669580008667374

- Atkinson, R, 1998. The life story interview. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Beeka, B & Rimmington, M, 2011. Tourism entrepreneurship as a career choice for the young in Nigeria. Tourism Planning & Development 8(2), 215–23. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2011.573924

- Carlisle, S, Kunc, M, Jones, E & Tiffin, S, 2013. Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tourism Management 35, 59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.05.010

- Christian, M, Fernandez-Stark, K, Ahmed, G & Gereffi, G, 2011. The tourism global value chain: Economic upgrading and workforce development (p. 276). Duke University, Durham, NC.

- Christian, M, 2012. Economic and social up (down) grading in tourism global production networks: Findings from Kenya and Uganda. Capturing the gains. Working Paper No. 11. Duke University, Durham, NC.

- Dawson, C & Henley, A, 2012. “Push” versus “pull” entrepreneurship: An ambiguous distinction? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 18(6), 697–719. doi: 10.1108/13552551211268139

- Echtner, C, 1995. Entrepreneurial training in developing countries. Annals of Tourism Research 22(1), 119–34. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(94)00065-Z

- Ellis, F, 1999. Rural livelihood diversity in developing countries: Evidence and policy implications (No. 40). Natural Resource Perspectives (p. 10).

- Gartner, C & Cukier, J, 2012. Is tourism employment a sufficient mechanism for poverty reduction? A case study from Nkhata Bay, Malawi. Current Issues in Tourism 15(6), 545–62. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2011.629719

- Kauppila, P, Saarinen, J & Leinonen, R, 2009. Sustainable tourism planning and regional development in peripheries: A Nordic view. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 9(4), 424–35. doi: 10.1080/15022250903175274

- Kirsten, M & Rogerson, CM, 2002. Tourism, business linkages and small enterprise development in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 19(1), 29–59. doi: 10.1080/03768350220123882

- Koens, K & Thomas, R, 2015. Is small beautiful? Understanding the contribution of small businesses in township tourism to economic development. Development Southern Africa 32(3), 320–32. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2015.1010715

- Kokkranikal, J & Morrison, A, 2011. Community networks and sustainable livelihoods in tourism: The role of entrepreneurial innovation. Tourism Planning & Development 8(2), 137–56. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2011.573914

- Lerner, M & Haber, S, 2001. Performance factors of small tourism ventures. Journal of Business Venturing 16(1), 77–100. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00038-5

- Lundberg, C & Fredman, P, 2012. Success factors and constraints among nature-based tourism entrepreneurs. Current Issues in Tourism 15(7), 649–71. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2011.630458

- McGrath, SA, 2005. Skills development in very small and micro enterprises. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Medina-Muñoz, DR, Medina-Muñoz, RD & Gutiérrez-Pérez, FJ, 2016. The impacts of tourism on poverty alleviation: An integrated research framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24(2), 270–98.

- Meyer, D, 2009. Pro-poor tourism: Is there actually much rhetoric? And, if so, whose? Tourism Recreation Research 34(2), 197–99. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2009.11081591

- Mitchell, J, 2012. Value chain approaches to assessing the impact of tourism on low-income households in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 457–75. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2012.663378

- Mitchell, J & Ashley, C, 2010. Tourism and poverty reduction: Pathways to prosperity. Earthscan, London.

- Mitchell, J, Font, X & Li, S, 2015. What is the impact of hotels on local economic development? Applying value chain analysis to individual businesses. Anatolia 26(3), 347–58. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2014.947299

- Morrison, A & Teixeira, R, 2004. Small business performance: A tourism sector focus. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 11(2), 166–73. doi: 10.1108/14626000410537100

- Nyaupane, GP & Poudel, S, 2011. Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 38(4), 1344–66. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.006

- Pillay, M & Rogerson, CM, 2013. Agriculture-tourism linkages and pro-poor impacts: The accommodation sector of urban coastal KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Applied Geography 36, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.005

- Polkinghorne, DE, 2005. Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counseling Psychology 52(2), 137–45. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137

- Robinson, OC, 2014. Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology 11(1), 25–41. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

- Rogerson, CM, 2008a. Integrating SMMEs into value chains: The role of South Africa’ s tourism. Africa Insight 38, 1–19.

- Rogerson, CM, 2008b. Tracking SMME development in South Africa: Issues of finance, training and the regulatory environment. Urban Forum 19(1), 61–81. doi: 10.1007/s12132-008-9025-x

- Rogerson, C, 2012. The tourism-development nexus in sub-Saharan Africa. Africa Insight 42(2), 28–45.

- Rogerson, C, 2014. Strengthening tourism-poverty linkages. In Lew, AA, Hall, CM & Williams, AM (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to tourism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Oxford.

- Rowley, G, Purcell, K, Richardson, M, Shackleton, R, Howe, S & Whiteley, P, 2000. Employers skill survey: Case study hospitality sector.

- Saarinen, J & Rogerson, CM, 2014. Tourism and the millennium development goals: Perspectives beyond 2015. Tourism Geographies 16(1), 23–30. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2013.851269

- Scheyvens, R, 2007. Exploring the tourism-poverty nexus. Current Issues in Tourism 10(2), 231–54. doi: 10.2167/cit318.0

- Scheyvens, R, 2009. Pro-Poor tourism: Is there value beyond the rhetoric? In Singh, TV (Ed.), Critical debates in tourism (pp. 124–132). Channel View Publications, Bristol.

- Scheyvens, R, 2011. Tourism and poverty. Routledge, New York.

- Scheyvens, R & Russell, M, 2012. Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: Comparing the impacts of small- and large-scale tourism enterprises. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 417–36.

- Skokic, V & Morrison, A, 2011. Conceptions of tourism lifestyle entrepreneurship: Transition economy context. Tourism Planning & Development 8(2), 157–69. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2011.573915

- Snyman, S & Spenceley, A, 2012. Key sustainable tourism mechanisms for poverty reduction and local socioeconomic development in Africa. Africa Insight 42(2), 76–93.

- Stoffelen, A & Vanneste, D, 2016. Institutional (Dis)integration and regional development implications of whisky tourism in Speyside, Scotland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 16(1), 42–60. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2015.1062416

- Thomas, R, Shaw, G & Page, SJ, 2011. Understanding small firms in tourism: A perspective on research trends and challenges. Tourism Management 32(5), 963–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.003

- Truong, VD, Hall, CM & Garry, T, 2014. Tourism and poverty alleviation: Perceptions and experiences of poor people in Sapa, Vietnam. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22(7), 1071–89. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.871019

- Vanneste, D & Ryckaert, L, 2011. Networking and governance as a success factor for rural tourism? The perception of tourism entrepreneurs in the Vlaamse Ardennen. Bulletin de La Société Géographique de Liège 57, 53–71.

- Wall, G & Mathieson, A, 2006. Tourism: Changes, impacts, and opportunities. Pearson Education, Harlow.

- Zhao, W, Ritchie, JRB & Echtner, CM, 2011. Social capital and tourism entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research 38(4), 1570–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.02.006