ABSTRACT

Following on from earlier work dealing with the role of metropolitan municipalities in managing urbanisation, this article assesses the role played by secondary cities in this regard. Although secondary cities have largely provided adequate infrastructure in line with the demands of population growth, three differences between metropolitan municipalities and secondary cities should be noted. First, on most indicators, secondary cities have more outliers than do metropolitan municipalities. Second, household incomes in secondary cities remain lower than those in metropolitan municipalities. Third, the ability of secondary cities to provide basic infrastructure does not differ much from that of metropolitan municipalities. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that, in terms of certain indicators, secondary cities have managed to deliver these faster than their metropolitan counterparts. We argue that the progress made in secondary cities during the period under consideration cannot be separated from the fact that the economic growth in more than 50% of secondary cities has been linked either to mining or to another dominant economic driver.

1. Introduction

The role of secondary citiesFootnote1 in managing urbanisation is a common topic in international literature (Adepoju, Citation1983; Otiso, Citation2005; Klaufus, Citation2010; World Bank, Citation2010). The initial literature on the relationship between secondary cities and urbanisation focused on the development of a balanced settlement structure and the prevention of too much urbanisation of the core urban areas (Rondinelli, Citation1983; Hardoy & Satterthwaite, Citation1986). More recently, the emphasis has shifted to managing urbanisation in order to manage social change in society (World Bank, Citation2010). The mere fact that 60% of the world’s urban people reside in cities with fewer than one million inhabitants confirms the importance of studying secondary cities and urbanisation (Roberts, Citation2014). However, empirical evidence as to how cities manage urbanisation is not always available. A recent study focusing on metropolitan municipalities in South Africa found that employment growth tended to coincide with demographic trends and that metropolitan municipalities managed to provide adequate infrastructure, but that population and household growth outstripped the provision of affordable housing (Turok & Borel-Saladin, Citation2014). Even if some work was done on the secondary city theme in the early 1990s (Van der Merwe, Citation1992; Urban Foundation, Citation1994) and even if there has recently been an upswing in the amount of work done in this regard in South Africa (SACN, Citation2012, Citation2014; Marais, Citation2016; Marais et al., Citation2014, Citation2016), the body of research nevertheless remains small. Much of the urban research is still dominated by work on the metropolitan municipalities (Visser, Citation2013; Visser & Rogerson, Citation2014).

With a view to assessing the role of secondary cities in the management of urbanisation in South Africa, we compare secondary cities with metropolitan municipalities as analysed by Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014). We argue that the South African secondary cities play as important a role as metropolitan municipalities do in terms of managing urbanisation. Nonetheless, because of the relationship between mining growth or of being subjected to another dominant economic sector (mostly in manufacturing) in the development of some these cities, the long-term prospects of these cities are closely related either to the demand for commodities or to the fluctuations associated with a dominant economic sector. Their dependence on mining or a single economic sector increases the long-term economic risks of many of these secondary cities. Like Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014), we use census data for 2001 and for 2011 across a range of economic and social indicators. Essentially, Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014) used a set of indicators and asked whether metropolitan municipalities had managed to provide the basic employment, infrastructure and housing to enable them to deal with the increases in population and in the number of households in metropolitan municipalities. These indicators include population growth as reflected in the total population, people employed, average household income, the number of households with access to indoor taps, the number of households with piped water inside the dwelling, households with no electricity and households living in informal dwellings. In our attempt to assess the situation in secondary cities, we used the same indicators as Turok & Borel-Salladin (Citation2014) with a view to determining the extent to which secondary cities have managed to deal with urbanisation. We then compared this finding – using similar indicators – with those of the previous study on metropolitan municipalities. More specifically, we asked whether the provision of infrastructure had managed to keep track with population growth (including household growth) and employment provision.

There is no universally acknowledged definition of secondary cities. Whereas Hardoy & Satterthwaite (Citation1986) claim that four key indicators – size, population, function and location – should play a role in identifying secondary cities, more recent literature emphasises the systems into which secondary cities are embedded (Roberts & Hohmann, Citation2014). The proponents of the latter approach suggest that secondary cities are differently linked to existing systems and that they perform different functions than other settlement types. Unlike the situation pertaining to metropolitan municipalities, there is no legal definition of secondary cities in South Africa. We have taken a list of 21 municipalities provided by the National Treasury in South Africa to represent the sample of secondary cities. (A full list is presented in , and provides an overview of the location of these settlements in South Africa.) This list is largely informed by population size, but the inclusion of //Khara Hais (Upington) suggests that the National Treasury also considered the regional importance of places. We acknowledge that this list is somewhat arbitrary.

Table 1. Population growth in secondary cities, metropolitan areas and South Africa, 2001 and 2011.

Against this background, we start by reviewing the literature pertaining to secondary cities and the management of urbanisation. We then turn to a discussion of the data and how they relate to secondary cities, and compare economic and demographic trajectories in secondary cities and in metropolitan municipalities. After discussing the situation in respect of infrastructure, we reflect on the housing situation. Finally, a number of concluding comments are made.

2. Secondary cities and urbanisation

Secondary city research can be divided into two phases. The first phase (up to the late 1980s) represents the golden era of secondary city research (Rondinelli, Citation1983; Hardoy & Satterthwaite, Citation1986). A range of functional attributes characteristic of secondary cities was considered during this phase. While the research also included the role of secondary cities in managing the urbanisation processes in many countries, the original research on the relationship between urbanisation and secondary cities emphasised the importance of secondary cities in the deconcentration of the population of a country (Rondinelli, Citation1983; Otiso, Citation2005). The reason for this desire to deconcentrate the population by adopting secondary city policies was firmly rooted in the fear that the larger cities would grow too big to manage (Carroll, Citation1988). In this regard, Otiso (Citation2005:118) notes that ‘[T]he goal of controlling urbanisation was to be achieved by slowing down rural-urban migration to major cities, making intermediate-sized cities more attractive to migrants, and by improving the living standards of rural areas so as to reduce rural-urban migration’. Van der Merwe (Citation1992) points out that care should be taken not to over-plan the relationship between secondary cities and urbanisation, and suggests a self-selection process in identifying secondary cities and their roles in managing urbanisation.

A second aspect that received attention during this phase was an emphasis on the dual role of secondary cities (Rondinelli, Citation1983). The linkages between secondary cities and the larger metropolitan municipalities (and sometimes even international economies), and also the linkages between these secondary cities and their particular rural hinterlands, were prominent features of this dual function. The focus on the specific importance of the dual role of secondary cities continued in the second phase (from the early 1990s onwards). In this connection, Bolay & Rabinovich (Citation2004:408) come to the following conclusion: ‘ … the cities we studied, and by extension a number of urban agglomerations, have a double affiliation’. This double affiliation means that they mediate between rural areas and the larger urban areas. Part of this mediatory process involves managing urban growth while simultaneously supplying goods and services to the rural centres and to the growing urban centres.

The second phase of secondary city research differs markedly from the first phase. The World Bank (Citation2010:vi) is extremely critical of the notion of utilising intermediate cities to prevent urbanisation to larger urban settings: ‘Neither the magnitude of urbanisation nor the size of mega-cities should motivate policymakers to implement restrictive policies.’ The World Bank emphasises the fact that a substantial portion of urbanisation to secondary cities occurs in a natural way. This natural process of urbanisation should be managed well at the city level. Effectively, the question no longer is how secondary cities can be used to contain urbanisation. Rather, the World Bank (Citation2010:viii) argues, the issue is ‘how to prepare for it’ and how to reap the benefits associated with the relationship between urbanisation and economic growth in the process of managing the negative impacts. The World Bank (Citation2010) further contends that policy approaches towards managing urbanisation and the role of secondary cities in this process should be country specific. More importantly, policies dealing with urbanisation should consider rural–urban and inter-urban linkages – a point already made in existing South African research (Urban Foundation, Citation1994).

For the World Bank (Citation2010), this emphasis on the role of secondary cities in managing urbanisation is premised on two realities. First, 53% of the world’s urban dwellers reside in cities with a population of 500 000 or fewer. This reality ‘raises important questions about the process of managing urbanisation and delivery mechanisms for urban development assistance in the decade ahead’ (World Bank, Citation2010:vi). Secondly, there is a commonly held (although equally contested) assumption that well-managed urbanisation can help to alleviate poverty and promote development. The World Bank (Citation2010:v) therefore proposes that ‘[T]o reap the benefits of poverty reduction through increased urbanisation, countries require national urban strategies supported by new diagnostic frameworks’. Within this mindset, the premise is that secondary cities, by means of their role in urbanisation, help to foster economic growth and to alleviate poverty. It is also important to counter the negative effects of urbanisation by providing adequate infrastructure. Experience has shown that unmanaged urbanisation due to fiscal or capacity concerns could have negative implications for the environment, for the alleviation of poverty and for health (UN-Habitat, Citation2012).

South African urbanisation should be understood in its historical context. Influx control, forced relocations, pass laws and the policy of orderly urbanisation had to prevent black urbanisation. Although the overall objective of halting black urbanisation was by no means achieved, these policies served to slow down black urbanisation: the South African urbanisation rate increased from 42% in 1955 to 50% in 1985 and 55% in 1996 (Harrison & Todes, Citation2015). By the early 1990s, many of the policies and laws had been repealed. This resulted in a much more ‘natural’ process of urbanisation, which, in turn, led to substantial increases in the rate of urbanisation (Todes et al., Citation2010). There is evidence of substantially larger migration movements to the bigger cities – especially the five main metropolitan municipalities (Harrison & Todes, Citation2015). Whereas metropolitan municipal areasFootnote2 grew at 2.5% per annum between 1996 and 2011, secondary cities grew at 2% per annum over the same period (Marais et al., Citation2016). Admittedly, some metropolitan municipalities grew faster than others. Johannesburg grew at 3.5% per annum while Mangaung only managed a growth of 1.4% per annum between 1996 and 2011. One should, however, acknowledge that the population-growth profiles of some of the smaller metropolitan areas were more similar to those of secondary cities in the corresponding period.

Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014) identify three key aspects that are related to urbanisation in South Africa. First among these is the ability of urban managers to deal with an increasing demand for basic services. The second issue pertains to the ability of the economies of urban areas to carry the costs associated with the urban infrastructure that is required to deal with urbanisation. Finally, consideration should be given to the absorption ability of the labour market. The rest of this article will be devoted to a more detailed assessment of the said three aspects as they feature in secondary cities.

Finally, because there is a substantial link between secondary cities and mining, consideration should be given to government’s response to the problems of mining towns. In 2012, subsequent to the Marikana Massacre, government introduced the Strategy on the Revitalisation of Mining Towns. The underlying assumption in this strategy is that socio-economic and living conditions are the main concerns associated with mining towns. Although this might well be a valid identification of the problem, the strategy does not consider the boom–bust cycles associated with mining development (Marais & Nel, Citation2016). The strategy also emphasises large-scale housing and infrastructure-related investments in mining towns. What is more problematic is that the strategy makes no distinction between towns of mining growth and towns of mining decline. Thus, in addition to assessing the extent to which these secondary cities manage to deal with urbanisation, the article will also reflect on the broader strategic response to mining towns by the South African government.

3. Population and economic trajectories in secondary cities

Available evidence at the national level suggests that accelerated urban growth has occurred since influx control was repealed in the mid-1980s (Turok, Citation2014; Harrison & Todes, Citation2015). We have already alluded to the fact that this growth was uneven, even amongst metropolitan municipalities. These increased levels of urbanisation are also occurring in secondary cities. presents all of the secondary cities, and also indicates the main function of each city in brackets.

It is important to contextualise the overall role of secondary cities in managing urbanisation. Although secondary cities were home to 14% of the 2011 population (up from 13% in 2001), 19% of the population increase between 2001 and 2011 occurred in secondary cities. This suggests that substantial in-migration takes place towards secondary cities. The comparative figures for metropolitan municipalities indicate that nearly 40% of the 2011 population resided in these areas, and that approximately 60% of the population increase in South Africa occurred in metropolitan municipalities. Between 2001 and 2011, metropolitan municipalities thus had a slightly higher population increase (26%) than did secondary cities (23%) (see ). However, the figures for the metropolitan and secondary cities are substantially higher than the 16% increase pertaining to South Africa or the 10% increase pertaining to South Africa outside metropolitan municipalities. Although the scale of urbanisation to metropolitan municipalities is considerable, the figures also confirm the important role of secondary cities in managing urbanisation.

Secondary cities and metropolitan municipalities differ in respect of one issue: the variance between the places considered under each group happens to be larger in the case of secondary cities. In the case of metropolitan municipalities, the percentage change varied between 7% (Buffalo city) and 37% (Johannesburg). For secondary cities, this spectrum lies between –0.4% in Matjhabeng (the Free State Goldfields) and 61% in Steve Tshwete (Middelburg in Mpumalanga). These two extremes respectively represent mining decline in Matjhabeng (Marais, Citation2013) and mining growth in Steve Tshwete. In fact, increases in excess of 40% are also directly related to mining growth in Rustenburg (42%) and Emalahleni (43%). Furthermore, six of the seven places that experienced population change in excess of 30% were mining towns (Stellenbosch being the exception). Ironically, three of the four cities with less than 15% increase are also mining towns (Mafikeng being the exception). The important point apparent from the data is that in the secondary cities, more so than in the metropolitan municipalities, population increase or population decline is largely associated with either mining growth or mining decline. Beyond mining, the same trend is also applicable to areas with dominant economic sectors, for example Newcastle and Emfuleni in respect of manufacturing – both of these places had population increases of 10% or less. While some diversification has taken place towards manufacturing, both of these places are still strongly linked to the minerals–energy complex.

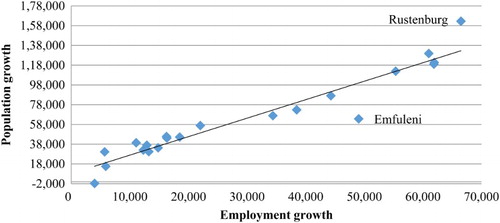

Next, the relationship between population increase and increase in employment will be considered. This relationship is important in that employment is the main source for household consumption, and also because, under apartheid, there was an explicit attempt to separate jobs from places of residence (Turok & Borel-Saladin, Citation2014) (see ). Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014:680) conclude that as far as the metropolitan municipalities are concerned, ‘[T]he pattern suggests a reasonably strong connection between the trends in jobs and people’.

Figure 2. Population versus employment growth in secondary cities in South Africa. Source: Stats SA (Citation2012).

The strong relationship noted between population increase and employment increase among metropolitan municipalities is also applicable to secondary cities, except in the case of two outlier cities – namely Rustenburg and Emfuleni. Rustenburg (owing to mining growth) has experienced both high population increase and high employment increase; population increase, however, has outstripped employment increase. Emfuleni (dependent on steel manufacturing) is an interesting case: employment increase has proportionally been higher than population increase, most probably as a result of Emfuleni’s proximity to Johannesburg, thus providing access to jobs in the greater Gauteng City region (Marais, Citation2016).

presents a more detailed pattern in respect of employment increase. According to Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014), approximately 60% of the employment increase in South Africa between 2001 and 2011 occurred in the metropolitan municipalities. We also know that these increases in the metropolitan areas of Gauteng and in Cape Town were substantially more than the average for secondary cities.

Table 2. Employment growth in secondary cities in South Africa.

The overall change in the absolute increase of employment tended to be slightly higher in metropolitan municipalities (43%) than in secondary cities (42%). Overall, 17% of employment increase occurred in secondary cities. The combined figure for metropolitan municipalities and secondary cities suggests that three out of every four jobs created in South Africa between 2001 and 2011 were created in either metropolitan municipalities or secondary cities. As we have already noted, the leading secondary city in respect of employment increase was Emfuleni, a fact that is probably attributable to that city’s proximity to Johannesburg. Employment levels in secondary cities are lower than those in the metropolitan municipalities. While approximately 48% of the adult population in the metropolitan municipalities were employed, only 44% (up from 39% in 2001) were employed in secondary cities.

Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014) found that increased employment also resulted in higher incomes in metropolitan municipalities. compares metropolitan data and secondary-city data. The evidence from this table indicates that incomes grew more rapidly in secondary cities than in metropolitan municipalities between 2001 and 2011. While average household income in secondary cities increased by 122% between 2001 and 2011, the comparative figure in metropolitan municipalities was only 98%. In 2011, however, the average household income in secondary cities was still lower than in metropolitan municipalities.

Table 3. Average household incomes, 2001 and 2011.

From this section on population and employment increase in secondary cities, it is clear that secondary cities play an important role in terms of accommodating increased urbanisation and employment in South Africa. However, economic vulnerability (mostly associated with mining or, in other cases, with single-sector dominance such as manufacturing) suggests that we should be cognisant of the fact that, within this group of secondary cities, there are a number of outliers that do not follow the basic pattern. Secondary cities also differ from metropolitan municipalities in that, in the former, unemployment is higher and household incomes are substantially lower.

4. Urban infrastructure in secondary cities

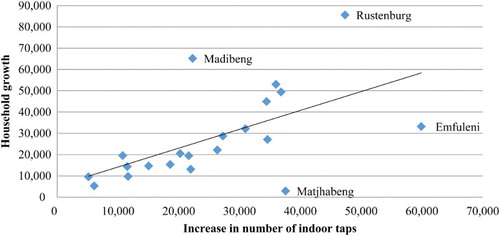

In this section, the focus falls on household increase and the ability of secondary cities to provide adequate infrastructure. Appropriate infrastructure has major economic, social, environmental and health benefits. The health benefits of appropriate infrastructure have already been indicated in both international (UN-Habitat, Citation2012) and South African (Marais & Cloete, Citation2014) research. compares household increase with the increase in the number of households that have access to piped water in their houses.

Figure 3. Household growth and the increase in the number of indoor taps, 2001 and 2011. Source: Stats SA (Citation2012).

A relationship between household increase and increased water infrastructure – while not as strong as the relationship between population growth and employment growth (as seen in ) – is apparent in 17 of the 21 secondary cities. There are, however, a few clear outliers. In the Platinum Belt cities of Madibeng and Rustenburg, household growth outstripped the growth in the number of households with indoor taps. Growth in infrastructure thus lagged behind population growth during the period in question. In Matjhabeng and Emfuleni, on the other hand, the increase in the number of households with indoor taps outstripped household growth. The population decline in Matjhabeng appears to have been a contributing factor in respect of enhanced infrastructure provision. In Emfuleni, the improvement seems to have been related to a directed attempt by the local and provincial governments to improve services – a point also made by Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014) in respect of the Gauteng metropolitan municipalities. Unfortunately, the data fail to reflect the reality of Emfuleni’s struggle to create sufficient capacity to deal with sewerage (Marais et al., Citation2016). presents a more detailed comparison between metropolitan municipalities and secondary cities in respect of indoor water access.

Table 4. Households with indoor water access in metropolitan and secondary cities, 2001 and 2011.

In respect of metropolitan municipalities, Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014:693) argue that ‘[T]he clear message is that each of the big cities has made very considerable progress in delivering an improved water supply to several hundred thousand local families … ’. The scale of this achievement in secondary cities, however, is substantially smaller: the percentage of households with indoor water increased from 33% in 2001 to 49% in 2011. Yet, at 105%, the rate of change outstrips that of the metros. The largest percentage increase was obtained in Rustenburg (nearly 200%); nevertheless, only 35% of households had indoor water access. Again, this outlier confirms the pressure associated with mining. It is also interesting that Matjhabeng, where mining decline was experienced, showed a considerable increase. The question that presents itself is that of how appropriate such investments really are in areas of mining decline.

Similar patterns are also visible in respect of improved sanitation (as measured in terms of access to flush toilets) (see ). The comparison of secondary cities and metropolitan municipalities in respect of infrastructural access to flush toilets indicates that, in 2001, secondary cities (60%) were substantially worse off than metros (75%). Although secondary cities were still trailing the metros in 2011, the percentage increase in secondary cities had been substantially higher (56%) than in metropolitan municipalities (40%). This higher percentage of change in secondary cities also reduced the gap between secondary cities from 15% in 2001 to 12% in 2011.

Table 5. Households with improved sanitation in secondary cities and metropolitan areas, 2001 and 2011.

The final infrastructural comparison concerns households with access to electricity (see ). Overall, the figures clearly demonstrate the considerable improvements in respect of access to electricity in the country over the past decade. From the table, it is clear that the number of households without access to electricity has declined considerably. In 2011, only 13% of households in secondary cities had no access to electricity. The comparative figure for metropolitan municipalities stood at 11%. There is evidence of substantial improvements in secondary cities: the percentage of households with no access to electricity dropped (by 10 percentage points) from 23% in 2001 to 13% in 2011. The comparative drop for metropolitan municipalities was eight percentage points.

Table 6. Proportion of households with no electricity access in secondary cities and metropolitan areas, 2001 and 2011.

Overall, the picture that emerges in respect of infrastructure provision in secondary cities suggests that in 2001 these cities had been in a less favourable position than metropolitan municipalities. Substantial improvements (in most cases better than in the case of metropolitan municipalities) had been realised by 2011. Yet the overall infrastructure levels remained lower than those in metropolitan municipalities. Of further significance is the variance among secondary cities, which illustrates the varied economic realities in these cities, as well as a dependency on commodities. Obviously, the longer-term question – namely that of how to deal with infrastructure if these cities were to lose people in large numbers (as is evident in Matjhabeng) – has not been asked.

5. Housing in secondary cities

In addition to infrastructure, access to housing is an important element of managing urbanisation. In South Africa, the history of urban management – which excluded black households from core urban areas – has led to substantial informal settlement developments in both the transitional period (1990–94) and the period after the democratic transition. South Africa consequently embarked on a comprehensive housing delivery process in 1994 and, as from the mid-2000s, on an informal settlement upgrading programme. A second factor, important to many mining areas in secondary cities, is that since the early 1990s mining companies have downscaled their historical housing of mineworker populations in single-sex hostels. Living-out allowances subsequently became a dominant feature of the policies of the mining companies in this regard. However, living-out allowances increased the pressure on local government to provide infrastructure, and did not automatically improve the living conditions of mineworkers (Marais & Venter, Citation2006; Cronje, Citation2014). highlights the fact that the number of households residing in informal dwellings in South Africa has increased. The Strategy on the Revitalisation of Mining Towns, however, emphasises the provision of new houses in mining towns.

Table 7. Number of households living in informal dwellings in secondary cities and metropolitan areas, 2001 and 2011.

According to Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014), the large metropolitan municipalities struggled more than the smaller ones to deal with the informal settlement problem. A number of points should be made with regard to secondary cities. Generally, the percentage of households residing in informal settlements in secondary cites declined from 23% in 2001 to 18% (similar to the figure for metros) in 2011. The Platinum Belt cities, namely Madibeng and Rustenburg, experienced the highest growth in absolute numbers, while other areas such as Matjhabeng and Matlosana (both areas of substantial mining decline) experienced the largest decline in the number of informal dwellings. Approximately 375 000 people were found to be residing in informal dwellings in secondary cities in 2011, which suggests that, as was the case in metropolitan municipalities, secondary cities were finding it difficult to provide adequate housing to these settlements.

6. Conclusion

While the paper by Turok & Borel-Saladin (Citation2014) focused on how metropolitan municipalities in South Africa have managed urbanisation, the present article has assessed the role of secondary cities in managing urbanisation. Secondary cities generally play an important role in this regard, as can be seen by the fact that population movement to secondary cities has coincided with employment patterns. Infrastructure provision in secondary cities has also managed to keep abreast of population increase. Unfortunately, secondary cities, similarly to metropolitan municipalities, have not necessarily always managed to provide adequate housing.

Despite these similarities, a number of differences between the metropolitan municipalities and secondary cities should be noted. The major differences are seen in the outliers among the secondary cities. Among many of these secondary cities, these outliers are visible in terms of population increase and infrastructure provision and are, in most cases, characterised by a dependency on mining or on any other single sector of the economy. On the one hand, high increases in the population creates pressure in respect of the provision of infrastructure; on the other, decline suggests that oversupply of basic infrastructure could create long-term problems. Secondly, while household income in secondary cities remains substantially lower than that in metropolitan municipalities, the employment rate in metropolitan municipalities is also higher than in secondary cities. Thirdly, infrastructure provision (on many of the indicators) in secondary cities has grown substantially more than in the case of metropolitan municipalities – although admittedly from a lower base, in many cases.

Finally, although the performance of secondary cities has equalled that of metropolitan municipalities on many of the indicators, the long-term vulnerability associated with a single sector (mostly mining) raises questions as to what the long-term implications of increase and decline associated with commodities will prove to be. In this respect, serious questions should be asked about the government’s ‘Strategy on the revitalisation of distressed mining areas’. For example, as this strategy intends, a focus on housing and infrastructure provision is the most appropriate if the long-term viability of the main economic sector happens to be uncertain. This could prove counter-productive in the long run. There already is evidence that this may be the case in Matjhabeng where the mining industry has shrunk. Although the figures for Rustenburg suggest that some form of infrastructure and housing investment is required, this should be approached with care. Consideration should at least be given to the alternative of rental housing in order to, in the future, reduce the risk of owning assets in undesirable locations. In addition, the notion of modular infrastructure should also be considered. Providing a modular infrastructure that can easily be dismantled and is therefore unlikely to give rise to long-term environmental concerns might well be the most appropriate route to take. The overall results also suggest that a concerted effort is required to increase the knowledge base associated with secondary cities. The literature on the importance of rural–urban and urban–urban linkages further suggests that much more research is required in this respect.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 While we use the term secondary cities, because our article emphasises these cities in relation to the eight metropolitan municipalities in South Africa, we acknowledge that there is merit in the use of terms such as intermediate cities or small cities in the international literature.

2 South Africa has eight metropolitan municipalities, as indicated in : Cape Town, Ekurhuleni, Tshwane, Johannesburg, eThekwini, Nelson Mandela Bay, Mangaung and Buffalo City. Originally, only the first six were declared metropolitan municipalities. In 2011, Mangaung and Buffalo City were added.

References

- Adepoju, J, 1983. Selected studies on the dynamics, patterns and consequences of migration – medium size towns in Nigeria. Unseco, Paris.

- Bolay, J & Rabinovich, A, 2004. Intermediate cities in Latin America risk and opportunities of coherent urban development. Cities 21(5), 407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2004.07.007

- Carroll, G, 1988. National city size distributions: What do we know after 67 years of research? Progress in Geography 21(1), 23–40.

- Cronje, F, 2014. Digging for development: The mining industry in South Africa and its role in socio-economic development. South African Institute for Race Relations, Johannesburg.

- Hardoy, J & Satterthwaite, D, 1986. Small and intermediate urban centres: Their role in national and regional development in the third world. Hodder and Stoughton, London.

- Harrison, P & Todes, A, 2015. Spatial transformations in a “loosening state”: South Africa in a comparative perspective. Geoforum 61, 148–162. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.03.003

- Klaufus, C, 2010. Watching the city grow: Remittances and sprawl in intermediate central American cities. Environment and Urbanization 22(1), 125–137. doi: 10.1177/0956247809359646

- Marais, L, 2013. The impact of mine downscaling on the Free State Goldfields. Urban Forum 24, 503–521. doi: 10.1007/s12132-013-9191-3

- Marais, L, 2016. Local economic development beyond the centre: Reflections on South Africas secondary cities. Local Economy, 31(1-2), 68–82. doi: 10.1177/0269094215614265

- Marais, L & Cloete, J, 2014. “Dying to get a house?” The health outcomes of the South African low-income housing programme. Habitat International 43(1), 48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.01.015

- Marais, L & Nel, E, 2016. The dangers of growing on gold: Lessons for mine downscaling from the Free State Goldfields, South Africa. Local Economy, 31(1-2), 282–298. doi: 10.1177/0269094215621725

- Marais, L & Venter, A, 2006. Hating the compound, but … Mineworker housing needs in post-apartheid South Africa. Africa Insight 36(1), 53–62.

- Marais, L, Van Rooyen, D, Lenka, M & Cloete, J, 2014. Planning for economic development in a secondary city? Trends, pitfalls and alternatives for Mangaung, South Africa. In Rogerson, C. & Szymańska, D. (Eds.), Bulletin of geography: Socio-economic series (no 26). Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń, pp. 203–217.

- Marais, L, Nel, E & Donaldson, R (Eds.), 2016. Secondary cities and development in South Africa. Routledge, London.

- Otiso, K, 2005. Kenya’s secondary cities’ growth strategy at a crossroads: Which way forward? GeoJournal, 62, 117–128. doi: 10.1007/s10708-005-8180-z

- Roberts, B, 2014. Managing systems of secondary cities. Cities Alliance, Brussels.

- Roberts, B & Hohmann, R, 2014. The systems of secondary cities: The neglected drivers of urbanising economies. Cities Alliance, Brussels.

- Rondinelli, D, 1983. Secondary cities in developing countries. Policies for diffusing urbanisation. Sage Publications, Beverley Hills.

- SACN (South African Cities Network), 2012. Secondary cities in South Africa: The start of a conversation. SACN, Johannesburg.

- SACN (South African Cities Network), 2014. Outside the core: Reflections: Towards an understanding of South Africa’s intermediate cities. SACN, Johannesburg.

- Stats SA (Statistics South Africa), 2012. Census data, 1996, 2001 and 2011. Stats SA, Pretoria.

- Todes, A, Kok, P, Wentzel, M, van Zyl, J & Cross, C, 2010. Contemporary South African urbanization dynamics. Urban Forum, 21, 334–348.

- Turok, I, 2014. South Africa’s tortured urbanisation and the complications of reconstruction. In Urban growth in emerging economies: Lessons from the BRICS. Routledge, London.

- Turok, I & Borel-Saladin, J, 2014. Is urbanisation in South Africa on a sustainable trajectory? Development Southern Africa, 31(5), 675–691. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2014.937524

- UN-Habitat, 2012. State of the world’s cities 2012/13: Prosperity of cities. UN-Habitat, Nairobi.

- Urban Foundation, 1994. Outside the metropolis: The future of South Africa’s secondary cities. Urban Foundation, Johannesburg.

- Van der Merwe, I, 1992. In search of an urbanization policy for South Africa: Towards a secondary city strategy. Geography Research Forum 12, 102–127.

- Visser, G, 2013. Looking beyond the urban poor in South Africa: The new terra incognita for urban geography? Canadian Journal of African Studies, 47(1), 75–93.

- Visser, G & Rogerson, C, 2014. Reflections on 25 years of urban forum. Urban Forum 25, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12132-014-9227-3

- World Bank, 2010. Systems of cities. Harnessing growth for urbanisation and poverty alleviation. Finance, economic and urban department, World Bank. World Bank, Washington, DC.