ABSTRACT

Even though Nigeria no longer remains so, in 2014 the country was declared ‘Africa’s biggest economy’ on the basis of its gross domestic product (GDP). It is a reality that many Nigerians still suffer deprivation and abject poverty. I argue that, as opposed to using GDP as a sole measure, multiple determinants need to be considered in order to convincingly validate the claim that Nigeria is Africa’s biggest economy because it was largely based on measurable economic output rather than the well-being of the populace. Using Martin Heidegger’s philosophy to question the structures in Nigeria which undermine ‘potentiality-for-being’, I show how Heidegger’s philosophy proffers possible solutions on how best to actualise proper potentiality-for-being. I also illustrate how the GDP of Nigeria is largely based on population and not on economic well-being. Lastly, refuting the use of GDP as the only determinant for economic progress, I propose the Heideggerian potentiality-for-being as a complementary determinant.

1. Introduction

The economic wealth in Nigeria is big and by land mass Nigeria is larger than France and Germany put together, which inevitably dwarfs many other countries on the continent. In 2014, the Nigerian gross domestic product (GDP) was calculated to be larger than South Africa’s which had previously been ranked the largest economy in Africa.Footnote1 Nigeria’s population is estimated at 183 million, which is the largest in the continent.Footnote2 The article published in the Economist titled ‘We Happy Few’ portrays that the declaration of Nigeria as the largest economy does call for celebration, at best for the happy few. In spite of the fact that the 2015 article ‘We Happy Few’ looks at the declaration of Nigeria as the largest economy from the viewpoint of the population, I think it is important to thematise the logistics used as a measure for this. The title, ‘We Happy Few’, nudges the mind to think about the economic injustices perpetrated in Nigeria, where a happy few continue to exploit the rest of the population. This is the case in many countries in Africa. In South Africa, for instance – like most African countries – the gap the between the well-offs and the poorest increases every second. South Africa’s position as the largest economy in Africa is largely based on economic outputs of only a small, very rich proportion of the country. The well-being of the poor majority was not factored into the processes leading to the decision.

This article seeks to beam the spotlight on Nigerian’s economic structures and on international structures which consciously or unconsciously promote this act of injustice seen in the unequal distribution of wealth. By an act of injustice, I refer to the social–economic reality of inequality caused by an unfair distribution of wealth. In focusing on Nigeria, I do not maintain that economic injustices are peculiar to Nigeria alone; rather, in fact, this research may have implications for African countries with similar economic structures to Nigeria. I focus on Nigeria because I seek to thematise the declaration of its GDP as the largest in Africa. I will argue that the use of GDP as the only determinant for measuring economic well-being is a conceptual injustice to any attempt at ensuring or promoting development. This is largely due to the fact that GDP focuses mainly on output and population growth, while little or no emphasis is put on well-being. Thus I argue that, more than just numbers, there is also a need to look at how well-being resonates with economic growth. My refutations of GDP as the only measurand for economic development will be backed with statistical and comparative illustrations. Lastly and most importantly, I will appeal to Martin Heidegger’s ‘potentiality-for-being’ and his preference for the need to consider Dasein (Being), concepts he espouses in his Being and Time (Heidegger Citation1962), as additional criteria for determining economic growth. This will help resolve the lapse that one finds in the use of GDP as the only determinant for economic development.

2. Nigeria’s economy

Nigeria is a country with enormous human, natural and economic resources. However, like most African countries, it has been plunged into high levels of inequality, poverty and unemployment, all of which are signs of underdevelopment. It is important to recognise the fact that some of the problems experienced in Nigeria today are due to the impact of colonialists’ ‘scramble for Africa’. A scramble based on egoistic motives and ‘political factors, such as nationalist rivalries and balance of political powers among the leading European nations and a quest for national glory’ (Sheldon, Citation1995:134). Addressing the effects of colonial legacy will shed light on the point that is being made by Gellar Sheldon.

Colonial invasion into Africa was and remains a major problem in Africa. In the case of Nigeria, the ‘divide and rule’ system was the method of governance used by the colonialists. This system saw the gradual destruction of the existing indigenous mode of government, consequently resulting in control and pillage of human and economic resources of the country through the slave trade, cheap labour and exploitation of mineral resources, among others. The struggle for independence marked the gradual end of colonial institutions and, one might argue, a considerable realisation of peace in Nigeria. However, scholars like Mahmood Mamdani maintain that colonial ideologies and mentality have been transformed and are not being replicated in post-colonial Africa. Mamdani blames this state of affairs on the analytical failure which has led to political and economic failures (Mamdani, Citation1996:29). The peace and joy that came with independence was short lived as the political climate after independence in Nigeria became marred by hegemony and ethnic bigotry.

On the one hand, the vanishing of the peace attained at independence is partly due to the bifurcated experiences and responses of Nigerians to the colonial experience. The northern part considered itself to be most influenced by the Arabs, and the eastern part and most parts of the south consider themselves to have been greatly influenced by British colonialists. This asymmetry or, rather, dissimilarity in the historical narrative brought about rancour between the different ethnic groups. This also slowly metamorphosed not only into an ethnic quest for hegemony, but also some religious conflicts and a dangerous ideology of territoriality in all spheres of life. This, as will be argued, eventually led to nepotism and mismanagement of resources in Nigeria because the intention was to use resources for the well-being of only a few. Simeon Ilesanmi articulates this colonialists’ impact when he observes that ‘by drawing people of different faith traditions into one geographical orbit, colonialism accentuated and broadened the provincialized pluralism that was already present in Nigeria’ (Ilesanmi, Citation1997:xx). This, as one would expect, was and continues to be a hindrance to indigenous leaders in their foray into politics.

Statistics show that from 1965 to 2004 Nigeria’s average material well-being saw an abysmal free fall. This resulted in the decline of average nutritional levels (the proportion of the population undernourished rose substantially), average consumer expenditure, available and accessible health care, and infrastructure (transport and communications degraded drastically due to inadequate maintenance) (Nafziger, Citation2006:18–19). With the following quote, let us cast the light on recent times:

The period 2001 to 2008 witnessed an average real GDP growth rate of about 5%. However, economic growth has not resulted in appreciable reduction in unemployment and poverty prevalence. This situation is attributable to a variety of factors that have persisted as important policy challenges and has led to several questions regarding inclusiveness in the poverty reduction process. (Kanayo, Citation2014:201–2)

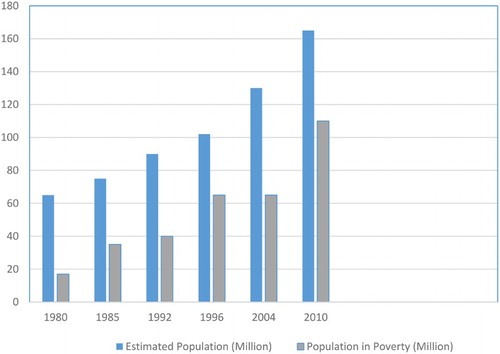

Although economic degradation is often tied up with corruption, political incompetency or ingenuity, social conditions and ethnic binary conceptions of identity, none of these factors will be the focus of this study. I am rather concerned with how economic dilapidation is partly due to a poor economic measurand, especially GDP, which gives little or no concern to the question about the meaning of Being. Being as proposed by Martin Heidegger will be explained in the next section. When an economic measure is used, it must resonate with all the facets of realities which it seeks to present a coefficient of, otherwise it ceases to be an accurate representation. The assuring false hope. This is false hope for a country like Nigeria, where the alleged GDP which is said to measure ‘economic development’ does not correspond with the actual situation of poverty on the ground. Figure 1 illustrates that the poverty rate in Nigeria is high regardless of the massive population. This is in corroboration with the statement of Martin Ravallion, who argues that ‘Ambiguous concepts make deceptive statistics’ (Ravallion, Citation2010:26). Use of GDP as the only determinant for economic progress does not effectively reflect the conditions of the people. Thus GDP, as a simplistic concept, does not present any more than a deceptive statistic.

Figure 1. Nigerian poverty profile – estimated population versus population in poverty. Source: Kanayo (Citation2014).

3. Gross domestic product

GDP is an economic measurand that dates back to the 1930s. In 1937, Simon Kuznets, an economist, presented the original formulation of GDP in his report to the US Congress, ‘National Income’ (Kuznets cited in Dickinson, Citation2011). His idea was to capture all economic production by individuals, companies and the government in a single measure, which should rise in good times and fall in bad. As Elizabeth Dickinson avers:

Out of the carnage of the Great Depression and World War II rose the idea of gross domestic product, or GDP: the ultimate measure of a country’s overall welfare, a window into an economy’s soul, the statistic to end all statistics. Its use spread rapidly, becoming the defining indicator of the last century. (Dickinson, Citation2011)

GDP is an estimate of market throughput, adding together the value of all final goods and services that are produced and traded for money within a given period of time. It is typically measured by adding together a nation’s personal consumption expenditures (payments by households for goods and services), government expenditures (public spending on the provision of goods and services, infrastructure, debt payments, etc.), net exports (the value of a country’s exports minus the value of imports), and net capital formation (the increase in value of a nation’s total stock of monetized capital goods). (Costanza et al., Citation2009:3)

There have been a number of arguments about the credibility of GDP, especially when it comes to measuring well-being. Could it be argued that the desire for GDP to do more than just measure output is simply to ask too much of the measurand, or, better still, can we argue that well-being is dependent on material wealth (Robson, Citation1924:14)? According to Robson, ‘when we speak of the dependence of well-being on material wealth … we refer to the flow or stream of well-being as measured by the flow or stream of incoming wealth and the consequent power of using and consuming it’ (Citation1924:14). This cannot be the case in a context like Nigeria because the flow of material well-being is largely controlled by a group of well-off individuals, and the worse-off have to settle for a small portion of the flow of material wealth. The complexities inherent in any attempt to equate well-being with GDP are evident. This is partly due to the fact that there is a presupposition in the use of GDP as an economy’s development measuring tool. This presupposition is one that, without considering well-being, assumes well-being as an aspect of life which is implied in the result from GDP’s statistical findings. To assume that well-being is considered without adequately prioritising well-being is an injustice to the task of ensuring an accurate account of development.

Some economists, like Ravallion, show how this injustice is perpetrated by economists when he writes:

The researchers who measure poverty using the national accounts admit that they are doing so partly as a matter of convenience; it is just a whole lot easier to do it this way than by going back to all those messy micro household-level data sets. (Ravallion, Citation2010:33)

Perhaps, this may be one of the major reasons why GDP has remained a measuring criterion for so long, despite scholars’ attempt to phase it out as the only measure of economic development. It is an easy and less rigorous way of measuring economic development.

Contrary to these arguments, one could say that the expectation on GDP is way more than it was designed for, especially as ‘GDP mainly measures market production, though it has often been treated as if it were a measure of economic wellbeing. Conflating the two can lead to misleading indications about how well-off people are and entail the wrong policy decisions’ (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:23; original emphasis). Is the problem in the misconception of GDP, or in the presupposed expectations when one thinks about any measuring mechanism in society? I argue that the latter is the case because any economy measurand has to consider well-being as the fundamental basis for any economics endeavour.

It would not be misleading to argue in support of Stiglitz that:

we see the world through lenses not only shaped by our ideologies and ideas but also shaped by the statistics we use to measure what is going on, the latter being frequently linked to the former. GDP per capita is the commonly used metric. (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:xix)

The danger is to fall into the trap of understanding progress in terms only of production regardless of how these productions come about. It remains an important task to ensure that all ideologies and statistics do not undermine the place of human beings. The fundamental question remains: does the GDP present an accurate account of well-being, or is it the case that it does not quite capture that important aspect of human beings? It has of course been argued that GDP measures economic coefficients and is not a measure of well-being. However, I argue that every measure must have well-being as its core.

3.1 Beyond GDP

Godelier compels us to ask two major questions when we want to address economic rationality: first, ‘How, in a given economic system, must economic agents behave in order to secure the objectives they set for themselves?’; and second, ‘What is the rationality of the economic system itself, and can it be compared with that of other systems?’ (Godelier, Citation1972:10–11). The first formulation seeks to make explicit the point that economic systems raise moral questions. This is because the moment the question of rationality is raised, we seek to understand the right and wrong behaviour. The second formulation sheds light on rationality by focusing on the capacity present in the metric in place to ensure growth of the means of production, enhancement in the standard of living, and on well-being in general, as well as the comparative yardstick (Godelier, Citation1972:11). The point that must be drawn from Godelier’s formulation is the need to consider the moral question in determining economic well-being, which is correlated with material well-being. Scholars like William Coleman have argued that ‘The economist is not a moralist’ (Coleman, Citation2004:123). As already emphasised in the early section of this study, the intention of GDP was to consider the economic problems in some countries which were struggling after World War Two. This circumstance by its very nature poses an ethical problem. In fact, there is no discourse about human beings that goes without any ethical underpinning, an ethical dimension that is either explicit or implicit. The very fact that economists want to use the right method in order to arrive at an uncompromising credible result already implies methodological ethics. The moment we talk about right and wrong, we are already talking about morality. The economists might not be moralists, but they operate on some moral guidance necessary for validating their statistics.

This moral issue demands the need to engage human realities more than it has been prioritised in economics. Despite the fact that well-being is presented in a simple way, it is complex. This is because it has to account for the very basic essential needs of a person and how these needs can be attained. This makes GDP an insufficient dictator of the defects in economic policies as far as well-being is at stake: ‘ … GDP has been widely used to measure the performance of individual countries over time and to compare performance among countries. As a measuring instrument, GDP is not free of flaws and internal contradictions’ (Morris, Citation2000:7). A major flaw in GDP is in its emphasis on economic coefficients regardless of economic well-being and the distribution of wealth.

The inadequacy of GDP is not a problem that is new: ‘In 1934, Simon Kuznets, the chief architect of the United States’ national accounting system, cautioned against equating GDP growth with economic or social well-being’ (Costanza et al., Citation2009:4). In 1959, Moses Abramovitz also questioned whether GDP accurately measures a society’s overall well-being. He cautions that ‘we must be highly skeptical of the view that long-term changes in the rate of growth of welfare can be gauged even roughly from changes in the rate of growth of output’ (Dickinson, Citation2011). Besides the outstanding concerns about the adequacy of the current use of solely GDP as the measure of economic coefficients, ‘there are even broader concerns about the relevance of these figures as measures of societal well-being’ (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:3). Although relevant for understanding an economics curve, there is obviously much more that GDP does not capture.

Two major concerns are inferred when one explores the report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress cited in Stiglitz et al. (Citation2010). One of the tasks of the commission was to explore feasibility measuring tools and to explore the disadvantages of GDP as the only measuring tool for economic progress. The first concern is evident when the former president of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, asserts that:

Our statistics and accounts reflect our aspirations, the values that we assign things. They are inseparable from our vision of the world and the economy, of society, and our conception of human beings and our interrelations. Treating these as objective data, as if they are external to us, beyond question or dispute, is … dangerous. (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:vii)

Second, ‘There is no single indicator that can capture something as complex as our society’ (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:xxv). The place of human beings comes out strongly in the statement by Sarkozy. To treat data as though they are not generated by human beings for the well-being of human beings is a problem. This postulation in the context of Nigeria, especially as it was declared Africa’s largest economic, is a clear sign that well-being is a major blind spot that has been ignored. The second point shows the complexity in the usage of a single economy check to determine the development of a multifaceted nature of human beings.

Given the increasing gap inherent in the information provided in aggregate GDP data and the situation of common people’s well-being, there is a need to emphasise the significance of well-being (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:11). GDP does not consider ‘well-being [which] has to do with both economic resources, such as income, and with non-economic aspects of people’s lives (what they do and what they can do, how they feel, and the natural environment they live in)’ (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:8). Ochangco refutes the use of a single measurand to analyse economic performance: in proposing a ‘pluralist-instrumentalist interpretation’, he argues that it is important to avoid ‘methodological monism’ in the interpretation of economic development (Ochangco, Citation1999:218–19). The only way one can understand how to ensure well-being is to explore the various ways human beings try to bring about capability. This is where the thoughts of Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) become very important for this study. Heidegger focuses not only on the ‘that’ (facticity) or the ‘what’ (constitution) of human beings, but he explores the ‘how?’ of human beings (Inwood, Citation1999:27). It is only in identifying the reality of human beings, in facticity and constitution, that we become better equipped (the ‘how?’) to respond to their realities.

4. Martin Heidegger’s ‘potentiality-for-being’

Martin Heidegger is a twentieth-century German philosopher prominent for his phenomenology approach. In his work Being and Time he makes an earnest effort ‘ … to return thought to the world whence it unfolds, to wrest it from the dangers of abstraction, or objective representation, and to return it to life’ (Beistegui, Citation2003:40–1). By using Heideggerian phenomenological method, I highlight the significance of an inter-disciplinary approach in the discourse of economics development, and I show how ontology contributes to the discourse. I also show how Heidegger’s prioritisation of the question about the meaning of Being is a methodology worth appropriating as a fundamental consideration in the discussion of economic growth. Heidegger uses the phenomenological–ontological enquiry to investigate the meaning of the question of Being. Heidegger uses the word Being (Dasein) to designate human beings. In this section, I will use Dasein, Being and human beings interchangeably. The word ‘phenomenological–ontological’ stems from ‘phenomenology’ and ‘ontology’. According to Robert Sokolowski, phenomenology is ‘the study of human experience and the ways things present themselves to us in and through such experience’ (Sokolowski, Citation2000:2). Ontology, as a branch of philosophy, asks the question of Being, and it is only possible or grasped as phenomenology (Heidegger, Citation1996:35). Heidegger’s phenomenological–ontological approach can be roughly defined as an inquiry into the meaning of Being in so far as it can be understood in the world. Heidegger’s approach can be read as an attempt to disentangle Being from some economists’ understanding of Being as that which is ‘present-at-hand’;Footnote4 that which can only be used to attain statistical outcomes. Heidegger indicates the importance of factoring in the complexities of human experience into the understanding of any attempt to quantify human reality. In addressing Being, Heidegger makes the understanding of Being the priority of any endeavour.

Phenomenology is important in this study because, as Inwood avers:

some matters, especially being itself, are hidden. Hidden not because we have not yet discovered them or have simply forgotten them, but because they are too close and familiar for us to notice or are buried under traditional concepts and doctrines. (Inwood, Citation1999:160)

In the case of economics, I charge that the use of GDP as the only measurand for economic development is a continuation of this traditional fraternisation which Inwood ascribes to this hidden nature of being which is yet present. In fact, when it comes to social issues, Heidegger maintains that:

[the] various social problems are symptomatic of the turn away from Being. He elaborates this idea here in his notion of thinking, or the authentic thought of being, intended as the alternative to traditional metaphysics that turns away from being. For Heidegger, the alienation of human being has its roots in the … forgetfulness of being. (Rockmore, Citation1999:96–7)

This forgetfulness is not only a metaphysical question but also a social question which requires rigorous intellectual engagement, especially if one is to consider the effect that the forgetting of being is already having on society. I argue that Heidegger’s awakening of our consciousness to the reality of Being (Dasein) is something that economists can draw from.

According to Heidegger, ‘Being lies in the fact that something is, and in its Being as it is; in Reality; in presence-at-hand; in subsistence; in validity; in Dasein in the “there is”. In which entities is the meaning of Being to be discerned’ (Heidegger Citation1996:26). For Heidegger, ‘the term “ontic” designates everything that exists’ (Safranski, Citation2002:150). As opposed to things which just exist in the world, which is merely ontic, Heidegger distinguishes Dasein from things when he maintains that Dasein has an ontological status. Safranski argues that ‘The term “ontological” designates the curious, astonished, alarmed thinking about the fact that I exist and that anything exists at all’ (Safranski, Citation2002:150). Dasein is aware of its Being and the existence of other Beings.

Heidegger tries to explore Being in ‘Being-in-the-world’. Being-in-the-world is an expression Heidegger uses to describe the fact that Dasein does not just experience the world as it is apart from it, but it is always already in the world (Safranski, Citation2002:154). What Heidegger does, especially in Being and Time, is to try to unpack the reality that surrounds Dasein’s everyday activities. The foundation for Heidegger’s new approach is a phenomenology of ‘mindless’ everyday coping as the basis of all intelligibility (Dreyfus, Citation1991:1). To have a true understanding when looking at Being does nothing except that it ‘de-experiences’ experience and ‘de-worlds’ the world, representing the space of events, the location of Being (Safranski, Citation2002:146). For Heidegger, the world becomes the big space where Beings live out their being not only with themselves but with others in relation to things.

There are many characteristics which Heidegger attributes to Dasein (see Heidegger, Citation1962), but this study will only look at Heidegger’s understanding of potentiality-for-being. Potentiality-for-being has to do with that which is possible for Dasein but has not become actual (Beistegui, Citation2003:27). Potentiality-for-being cannot be understood as separate from what Heidegger refers to as ‘projection’. Projection is the ability to actualise potentiality-for-being, or what Karl Lowith refers to as ‘capacity-for-being’ (Lowith, Citation1998:42). What is implied here is that Dasein cannot be understood away from its projection. For Heidegger, Dasein always projects; ‘project’ is an expression Heidegger uses to designate Dasein’s ability to desire and aspire towards something. Dasein is always directing itself at things with anticipation of a result (Inwood, Citation1999:178). This has to be done with dignity because Dasein is not merely ontic, like things are, but also ontological (human being). What Heidegger maintains here is that every human being has a project which is a potentiality for actualising a particular desire. In fact, non-projection is a projection of non-projection. To decide not to project is already a projection because non-projection can be likened to a dormant projection; thus, it immediately implies projection. Let me give an example to further buttress the understanding of projection in non-projection. For instance, in the recent past journalists have gone to protest grounds with their mouths covered. This can be interpreted as non-projection because they are silent. However, in this silence one can deduce a projection aimed at communicating a suppression of their freedom of speech.

Heidegger recognises the complexity inherent in Dasein’s desire to be more. This is why, for Heidegger, projection ‘ … is a self-mystification of Dasein which, so long as it lives, is never finished, entire, or completed, as any object might be, but always remains open for the future, full of possibilities. Dasein (being here) implies being possible (Moglich-sein)’ (Safranski, Citation2002:150). For Heidegger, satisfaction is a momentary reward of achievement derived from projection. As such, Dasein’s potentiality-for-being is an open and unending attempt to satisfy the instability of human desires. Heidegger avoids the tendencies which may allow human life (well-being) to escape us and draw attention to the question of Being. Human beings and their well-being have to be at the centre of any attempt to ensure potentiality-for-being. Heidegger does not present an explicit account of what might be considered here as quantitative representations of potentiality-for-being. Put differently, Heidegger does not furnish us with a measure for determining an accurate potentiality-for-being. However, implicit prerequisites for measuring or determining authentic potentiality-for-being can be deduced from Heidegger’s analysis.

Heidegger’s conceptualisation of Dasein as having projecting characteristics means that Dasein is constantly influenced by its ‘concerns’ and ‘care’Footnote5 for itself and, arguably, others. From this perspective, things in the world are viewed from the stand point of ‘for-the-sake-of’; in other words, things are conceived from the purview of equipmentalityFootnote6 aimed to achieve Dasein’s project(s). Dasein does things to the extent that it allows or lets entities be encountered as ‘ready-to-hand’ (Heidegger, Citation1962:199). Put differently, human endeavours are often geared towards carrying out actions that enable ends to be met so that they can have access to basic needs such as food, clothing and shelter. Things, therefore, have to be set in place to ensure that there are lots of options for Dasein’s projections.

From a ‘Heideggerian economic’Footnote7 point of view, it will be misleading to use GDP as the only measure for economic development because it does not prioritise Being and, thus, cannot capture the complex reality of Dasein. Potentiality-for-being points to the fact that Being is always a potential which is waiting to be fulfilled. The real measure of potentiality-for-being is the availability of capabilities for agency, and the resources necessary for the actualisation of potentiality. Because this potentiality is based on what Dasein ‘cares’Footnote8 about, it is important to have adequate measurands in place in order to efficiently indicate when Dasein potentiality-for-being has been actualised or not and to present sufficient justifications by way of phenomenological proof on why potentiality has not been actualised. An immanent problem is that Heidegger’s potentiality-for-being is not something that can be captured in a measurand. Nevertheless, Heidegger’s philosophy highlights a fundamental consideration for any measurand which I believe calls for a revision of the understanding of any economic measure.

5. Revising GDP as the sole measurand for economic development

As already emphasised, well-being is an interwoven web of different structures; to think of well-being as one structure and not the other is to lose sight of the multiple compositions of the very nature of well-being (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, Citation2007:62–3). From an economist’s perspective, the priority that is given to Being is not entirely peculiar to Heidegger. Actually, economists like Amartya Sen, Joseph Stiglitz and many more have engaged the significance of well-being when addressing the topic of human beings. However, Heidegger’s emphasis on the prioritisation of human beings makes his potentiality-for-being a unique contribution to economics. A Heideggerian economist, if you like, presents a different dimension which makes Being as a major concern. The prioritisation of Being, in Heidegger’s Being and Time, is significant because he draws attention to human experience as a significant point of departure in the endeavour to understand the human reality.

The fact that GDP does not present an adequate measure of well-being makes it necessary, as I have argued thus far, to rethink GDP as the sole measure of development. Heidegger’s potentiality-for-being, which emphasises the need to consider human beings, adds an important dimension in the endeavour to revisit GDP’s effective and sufficient measuring ability. This study does not undermine the significance of GDP, but rather questions its credibility or accuracy in the attempt to effectively measure economic coefficients and, by extension, well-being in its measure of economic development. The economic situation in Nigeria, as already emphasised, does not reflect the findings of GDP which ranked Nigeria, in 2014, as Africa’s largest economy. Dilapidated infrastructures, poor health care, a high rate of unemployment, a high rate of poverty and an ineffective education system, among others, remain realities in Nigeria. The desire to actualise potentiality-for-being, through effective consideration of well beings, is not being fulfilled in Nigeria. In fact, quality of life in Nigeria does not correspond with the claim that Nigeria is the largest economy in Africa. The claim, if true, is mainly based on the population rather than on the quality of life – well-being.

Scholars like Sen have also argued along the lines of Heidegger’s focus on Being. In Sen’s discourse, ‘to have a capability is to be capable of achieving a range of what he calls “functioning”’ (Cohen, Citation1993:21). Functionings are the activities or the things someone does (Cohen, Citation1993:21). In an attempt to also ensure adequate measurement of human development, the:

… UNDP [United Nations Development Programme] has constructed another alternative measure of welfare, the Human Development Index. The HDI summarises a great deal of social performance in a single composite index combining three indicators – longevity (a proxy for health and nutrition), education, and living standards. (Nafziger, Citation2006:35–6)

There have been attempts to prove the inefficiency of basing economic development on the outcome of the statistical finding of only GDP. Stiglitz et al. also present a detailed analysis of how best to tackle the problem:

First, emphasise well-established indicators other than GDP in the national accounts. Second, improve the empirical measurement of key production activities, in particular the provision of health and education services. Third, bring out the household perspective, which is most pertinent for consideration of living standard. Fourth, add information about the distribution of income, consumption and wealth to data on the average evolution of these elements. Finally, widen the scope of what is being measured. (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010:26)

The concept of human development is much richer and more multifarious than what we can capture in one index of indicator. Yet HDI is useful in focusing attention on qualitative aspects of development, and may influence countries with relatively low HDI scores to examine their policies regarding nutrition, health and education. (Nafziger, Citation2006:39)

6. Conclusion

As I draw to a conclusion in this article, it only remains to ask whether Dickens was right when he wrote: ‘My satire is against those who see figures and averages, and nothing else – the representative of the wickedest and most enormous vice of our time’ (Coleman, Citation2004:113). My argument is that one of the major weaknesses is the use of only GDP. There is more to human experience than the use of one measurand. This is an outcry which requires an immediate response, especially in Nigeria.

It is not erroneous to think that ‘As human populations and economies have grown, it has become impossible to improve one’s own wellbeing without affecting other people’s’ (Prescott-Allen, Citation2001:1). However, this is partly due to the problem of calculating economic well-being in such a way that it does not reflect the actual situation of the worse-off, thus making it difficult to accurately determine what sector of the economy to improve. In effect, economists have to ensure that they keep up with political bias and obscurantism which is particularly evident in Nigeria and in some other African countries (Bauer, Citation1981:255).

Even when well-being is measured, it is important to consider multiple mechanisms in order to improve the accuracy of the outcome. This is evident when Prilleltensky and Prilleltensky write: ‘By focusing exclusively on subjective measures of well-being, we [might] fail to question the impact of contextual dynamics on people who report high levels of well-being despite living in very deprived community conditions’ (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, Citation2007:57). It is important to understand that even well-being is multi-dimensional in nature and comprises different potentialities or capabilities (Sahn & Young, Citation2010:372). The significance of appealing to more measuring systems as opposed to sticking to GDP also eliminates the economists’ methodological monism which Ochangco warns against.

Heidegger’s ‘potentiality-for-being’ reflects the irreducibility of the place of Being as far as well-being is concerned. The fact remains that this idea has been expressed in so many ways by different scholars but had received little or no response as far as implementation is concerned (Sahn & Young, Citation2010:372). My view is that more attention and acceptance have to be given to the idea that GDP, although important, cannot be, and should not be considered, the only measurand for economic development. The use of multivariate well-being comparisons will account for the correlation of the deprivations in different dimensions of well-being (Sahn & Young, Citation2010:374). It is only through this that economists will focus on Being and the potentiality-for-being and not on stern attempts to come up with figures. Potentiality-for-being is a rational space for formulating a foundational positive and pragmatic point of departure for analysing development. Potentiality-for-being is an awareness that cannot be fully captured in a measurand, but the awareness helps and must be prioritised in economists’ attempts to quantify human reality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

† This article was presented during the Social Science for Development Conference at Stellenbosch University, 9 to 10 September 2015.

1 South Africa has subsequently surpassed Nigeria and again occupies the top position in Africa.

2 ‘We Happy Few’, 20 June 2015. http://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21654359-nigerias-population-has-been-systematically-exaggerated-we-happy-few. Accessed 7 July 2015.

3 For the purpose of emphasis: ‘Poverty and inequality are global phenomenon but the rates in Nigeria are higher than most countries in the world. Since the 1980s, the poverty rate has been trending significantly downward in all regions of the world except in subSaharan Africa (SSA)’ (Kanayo, Citation2014:204). Without exaggerating, it is important to recognise that the wealth in Nigeria is often controlled by the rich, and the poor have to live off trickle-down from the well-off.

4 In talking about being present-at-hand, Heidegger argues that its nature is that of ‘serviceability’, ‘conduciveness’, ‘usability’ and ‘manipulation’ (Heidegger, Citation1962:97).

5 According to Inwood, Heidegger uses the word ‘care’ to mean ‘to get, acquire, or to provide something for oneself or someone else’ (Inwood Citation1999:35).

6 By equipmentality, Heidegger maintains things are meant to be used as equipments in order to achieve Dasein's end. In order words, things are means to what Dasein' considers as ends. Heidegger makes the distinction between things and Dasein because he wants to highlight the fact that Dasein does not belong to the category of things.

7 Heidegger might not consider his thinking as economics in nature, but I am compelled to read economics thought into his potentiality-for-being and in fact in other aspects of his philosophy. Hence, a Heideggerian economics.

8 ‘Heidegger uses the term [Care] in the meaning of providing, planning, looking after, calculating, foreseeing’ (Safranski, Citation2002:157).

9 It has been argued that ‘The researchers who measure poverty using the [GDP means obtained from the] national accounts admit that they are doing so partly as a matter of convenience; it is just a whole lot easier to do it this way than by going back to all those messy micro household-level data sets’ (Ravallion, Citation2010:33).

References

- Bauer, PT, 1981. Equality, the third world and economic delusion. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London.

- Beistegui, M, 2003. Thinking with Heidegger. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- Cohen, GA, 1993. Equality of what? On welfare, goods, and capabilities. In Nussbaum, M & Sen, A (Eds.), The quality of life. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Coleman, OW, 2004. Economics and its enemies: Two centuries of anti-economics. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

- Costanza, R, et al, 2009. Beyond GDP: The need for new measure of progress. http://www.bu.edu/pardee/files/documents/PP-004-GDP.pdf Accessed 7 August 2015.

- Dickinson, E, 2011. GDP: A brief history. http://foreignpolicy.com/2011/01/03/gdp-a-brief-history/ Accessed 6 August 2015.

- Dreyfus, H, 1991. Being-in-the-world: A commentary on Heidegger’s being and time. MIT Press, New Baskerville.

- Godelier, M, 1972. Rationality and irrationality in economics. Monthly Review Press, New York.

- Heidegger, M, 1962. Being and time. Trans. John Macquarrine and Edward Robinson. Harper & Row, New York.

- Heidegger, M, 1996. Being and time. Trans. Joann Stamburg. University of New York Press, Albany.

- Ilesanmi, SO, 1997. Religious pluralism and the Nigeria state. Africa Association for the Study of Religion, Athens.

- Inwood, M, 1999. A Heidegger dictionary. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

- Kanayo, O, 2014. Poverty incidence and reduction strategies in Nigeria: Challenges of meeting 2015 MDG targets. http://www.krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JE/JE-05-0-000-14-Web/JE-05-2-000-14-Abst-PDF/JE-5-2-201-14-133-Kanayo-O/JE-5-2-201-14-133-Kanayo-O-Tx[8].pdf Accessed 8 August 2015.

- Lowith, K, 1998. Martin Heidegger and European nihilism. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Mamdani, M, 1996. Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the late colonialism. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Morris, MD, 2000. Measuring the condition of the world’s poor: The physical quality of life index. Pergamon Press, New York.

- Nafziger, EW, 2006. Economic development. 4th edn. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Ochangco, CA, 1999. Rationality in economic thought: Methodological ideas on the history of political economy. Edward Elgar, Chelternham.

- Prescott-Allen, R, 2001. The wellbeing of nations. Island Press, Washington.

- Prilleltensky, I & Prilleltensky, O, 2007. Webs of well-being: The interdependence of personal relational, organizational and communal well-being. In Haworth, J & Graham, H (Eds.), Well-being individual, community and social perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 57–76.

- Ravallion, M, 2010. The debates on globalization, poverty, and inequality: Why measurement matters. In Anand, S, Segal, P & Stiglitz, JE (Eds.), Debates on the measurement of global poverty. Oxford University Press, New York, 25–41.

- Robson, AW, 1924. The relation of wealth to welfare. George Allen & Unwin, London.

- Rockmore, T, 1999. Heidegger and French philosophy: Humanism, antihumanism and being. Routledge, New York.

- Safranski, R, 2002. Between good and evil. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Sahn, ED & Young, DS, 2010. Living standards in Africa. In Anand, S, Segal, P & Stiglitz, JE (Eds.), Debates on the measurement of global poverty. Oxford University Press, New York, 372–426.

- Sen, A, 1993. Capability and well-being. In Naussbaum, M & Sen, A (Eds.), The quality of life. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 30–53.

- Sheldon, G, 1995. The colonial era. In Martin, PM & O'Meara, P (Eds.), Africa. 3rd edn. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- Sokolowski, R, 2000. Introduction to phenomenology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Stiglitz, EJ, Sen, A & Fitoussi, J, 2010. Measuring our lives: Why GDP doesn’t add up. The New Press, New York.