ABSTRACT

Unemployment in South Africa has multiple causes. This article uses a district pseudo-panel to estimate the elasticity of labour demand, labour supply and unemployment with respect to wages. We assess whether hiring decisions are more sensitive to increases in wages of low-paid workers than high-paid workers, and whether wage growth prompts entry into the labour market. These channels combine to result in the positive causal effect of wage growth on unemployment. The research investigates whether these effects are dominated by districts in which unionisation rates are high and employment is concentrated in large firms. Wage growth of middle-paid to highly paid workers – as opposed to low-paid workers – reduces local labour demand and raises local unemployment. Bargaining arrangements correspond closely to the spatial wage distribution; in turn, a large part of the impact that wage growth has on labour market outcomes is determined by these wage-setting institutions.

1. Introduction

High unemployment in South Africa has been attributed to various contributing factors: rising labour supply, structural economic changes (and accompanying skills shortages) and high labour costs have all been cited as constraints to eliminating a long job queue (Bhorat & Hodge, Citation1999; Casale & Posel, Citation2002; Banerjee et al., Citation2008; Behar, Citation2010). The last reason is a point of contention: sectoral and firm-level estimates show that labour demand is highly sensitive to rising labour costs (Behar, Citation2010; Fedderke, Citation2012) and, the converse, wage demands do not respond to high local unemployment rates in the short run (Von Fintel, Citation2015); on the other hand, wages do adjust to local labour market conditions in the long run, while other studies contend that high wage demands and industrial action are not out of line with respect to other relatively low-unemployment economies (Bhorat et al., Citation2014). The recent implementation of a youth wage subsidy is a policy that specifically targets firms’ unwillingness to hire seemingly expensive young workers, and has shown to be promising in its success in experimental settings (Levinsohn et al., Citation2014), but less so after the policy’s immediate implementation in the broader labour market (Ranchhod & Finn, Citation2014). This also suggests that the cost of labour may be one binding constraint on job creation in South Africa. Furthermore, in light of the discussion around the implementation of a national minimum wage, the political economy debate weighs up the imperative of achieving living wages for workers against employment losses due to higher wages, coupled with a possible increase in the capital intensity of production.

This research re-examines the question of the sensitivity of the labour market to wages, but turns to a household (as opposed to a sectoral or firm) perspective. The research estimates wage–employment elasticities and then extends this to measure the sensitivity of participation in the labour market, and ultimately unemployment, to rising labour costs. Furthermore, the use of household data enables this analysis to be estimated in a way that distinguishes the influence of the demands of high-wage and low-wage workers on unemployment. Should labour demand be sensitive to increases in the wages of the best-paid workers only, it is likely that legislation such as national minimum wages will not increase the unemployment rate to a large degree. The opposite proposition is naturally also equally possible, with elastic labour demand in response to changes in wages of low-paid workers potentially triggering great disemployment effects with the implementation of national minimum wages.

This article estimates dynamic panel data models to account for the possible existence of bi-directional causality between wages and other labour market outcomes,Footnote1 and also for unobservable region-specific conditions (which Von Fintel [Citation2015] shows to be important in separating long-run from short-run labour market relationships). We investigate whether the importance of labour supply growth in driving unemployment in South Africa occurs through the pull of better monetary incentives, or whether the dominant accepted causality – namely that high wage demands depress employment creation – suffices to explain the role that labour costs have in contributing to unemployment. The article furthermore investigates whether institutionalised wage-setting arrangements, such as working in highly unionised districts or those with high concentrations of large firms, can account for the transmission of wage growth to higher unemployment.

The next section of this article briefly considers the relationship between wages and other labour market outcomes, while Section 3 outlines the estimation strategy using household pseudo-panel data. Section 4 discusses the results, while Section 5 concludes.

2. Causal chains between wages and unemployment

Separate strands of literature attribute the rise in post-apartheid unemployment to various sources. Some authors focus on the effects that high labour costs have on limiting labour demand (Fedderke, Citation2012; Klein, Citation2012; Magruder, Citation2012) and which lead to the substitution of labour with capital (Behar, Citation2010). Wages are the central concern. On the other hand, it is now well documented that large increases in labour force participation (supply side) is a defining feature of South Africa’s unemployment trajectory since 1994 (Branson & Wittenberg, Citation2007; Banerjee et al., Citation2008; Burger & von Fintel, Citation2014). The reasons for this demographic shift are often external to the labour market, including changing household formation patterns, increases in educational attainment and shocks to school enrolment policies (Casale & Posel, Citation2002; Burger et al., Citation2015). Yet the potential influence that rising wages have on motivating individuals to enter the labour force is not well understood in South Africa; additionally, the channel of rising wages’ effect on unemployment by increasing labour supply (as opposed to limiting employment) has not been explored.

If markets were to behave in a Walrasian fashion, wages would fall in order to clear surplus labour and eliminate unemployment (excluding frictional unemployment), while they would rise if labour shortages existed. In most instances, however, wages are moving downwards and unemployment is above zero (Altonji & Devereux, Citation1999; Barattieri et al., Citation2014). Structural unemployment entails that simultaneous labour shortages and surpluses can exist (but of different types of workers), with wage adjustments not being able to eliminate the long-run imbalances in the labour market (Bhorat & Hodge, Citation1999). In particular, highly skilled workers are in excess demand, while less skilled workers are in excess supply. In this context, wage increases of highly skilled workers may be coupled with small or zero disemployment effects; in contrast, the capacity to increase the remuneration of unskilled workers is either limited or accommodated with job loss.

Time-series statistics since the 1970s suggest that higher unskilled wages correspond with rising unemployment until 2000 and that a sluggish demand for this type of worker has emerged, while better skilled workers have not faced the same difficulties (Lewis, Citation2001). However, it is also possible that an equilibrium has emerged in which the labour market has favoured the creation of high-skill jobs at a wage premium, at the expense of the creation of unskilled work. This represents a substitution of labour types not necessarily because of cost, but because of a structural and/or sectoral shift in the product market (Bhorat & Hodge, Citation1999). This study will therefore differentiate between wage escalations of highly paid and poorly paid workers to assess the heterogeneous effects of wages on unemployment. In particular, we will study whether a new pattern has emerged, by which high unionisation rates at the middle to top of the distribution (as opposed to the bottom of the distribution) have changed the character of the wage–employment relationship in the post-apartheid period.

Despite these deviations from Walrasian theory, wages are nevertheless a mediating factor in regulating the labour market, and their actual relationship to labour demand and supply remains of interest in every context (Fedderke, Citation2012; Klein, Citation2012). However, the relationship between wage demands and other labour market outcomes is complex, and requires careful attention in isolating the role of wage-setting in influencing the rest of the labour market.

The rest of this section briefly considers the labour demand and supply channels through which wages potentially contribute to unemployment, along with the empirical considerations in identifying these channels.

2.1. Wages and labour demand

Wages and employment – and thus unemployment rates – are bi-directionally related, with each causal chain highlighting different features of how the labour market functions. Each involves the degree of bargaining that is possible. In the first instance, the wage curve literature (for instance) posits that wages depend on the slackness of local labour market conditions: high regional unemployment lengthens the job queue and, as a consequence, reduces the wage bargaining power of employees (Blanchflower & Oswald, Citation1990, Citation2008). Testing the validity of this line of causality for South Africa’s labour market was the objective of earlier work by Von Fintel (Citation2015). Where worker bargaining power is nevertheless able to become manifest in high-unemployment regions – through institutions such as unionisation and centralised collective bargaining – the impact of local labour market conditions is muted and the wage curve relationship is often found to be weaker or absent (Albaek et al., Citation2000; Blien et al., Citation2013; Daouli et al., Citation2013; Von Fintel, Citation2015).

On the other hand, the line of causality may run in the opposite direction, and is the primary objective of the current study: institutional bargaining may result in wage-setting that is decoupled from worker productivity, making it unprofitable for firms to hire workers, and consequently raises the unemployment rate (Fedderke, Citation2012; Klein, Citation2012; Magruder, Citation2012). In this case wages and unemployment rates would be positively related, as opposed to the negative coefficient implied by the wage curve theory. Hence, simply studying the correlation between wages and unemployment can be misleading, because the causal estimates in one direction or the other could have opposite signs and interpretations.

While the wage curve literature has proposed methods to separate the simultaneous processes from each other through the use of instrumental variables (Baltagi et al., Citation2012), few microeconometric studies have sought to interrogate the causal influence that wages exert on unemployment. This study proposes to fill this gap in a context where many commentators and authors allege that inflated wage demands constitute a partial explanation for high unemployment rates. In particular, South Africa’s economy is characterised by high degrees of labour bargaining, wage growth that often outstrips productivity growth and high unemployment (Wakeford, Citation2004; Klein, Citation2012). The question is whether these stylised facts are causally inter-related or co-incidentally correlated. While many authors have shown that collective bargaining and unionisation are successful at raising wages in South Africa (Hofmeyr & Lucas, Citation2001; Armstrong & Steenkamp, Citation2008; Bhorat et al., Citation2012; Magruder, Citation2012), Bhorat et al. (Citation2014) contend that the effects of unions have generally been benign when judged in light of the international context. South Africa’s strike intensity and union wage premia are not higher than comparable economies; however, its high unemployment rate remains an outlier. It is therefore not immediately clear that bargaining mechanisms directly contribute to high unemployment, or that bargaining can explain the full extent of unemployment, as acknowledged by Magruder (Citation2012). We investigate the veracity of these claims.

However, should the argument (that the union premium distorts the wage–productivity link) nevertheless hold true, it implies that wage growth among better paid unionised workers should have a greater negative effect on labour demand than those of poorly paid non-unionised workers. Sectoral and macro studies typically investigate the effects of average wages on employment, which in most countries represents the lowest part of the distribution.Footnote2 To more explicitly test the differential effects of unskilled and highly skilled workers in a market with structural employment, this article exploits the micro data to study the effects of changes in wages at different points in the distribution on labour market outcomes. The article distinguishes between the case where changes in wages at the middle to top of the distribution – which are typically set by unions or collective bargaining agreements – raise unemployment and the case where changes in wages at the bottom of the distribution (outside of the bargaining environment) have a defining role to play.

2.2. Wages and labour supply

Typically, labour supply elasticities using micro data relate individuals’ hours worked to the wages they are offered. Evers et al. (Citation2008) provide a recent review of this extensive literature. Empirically the main problems in estimating these elasticities are endogeneity and the selection bias that arises because the labour supplied (as measured by hours worked) of unemployed workers is not observed. Given the very high rate of unemployment in South Africa, we adapt the concept of labour supply to indicate whether individuals are willing to work at all (at the extensive margin) and not how long they are willing to work if they do have a job. As discussed in the following, a specific instrumental variables’ approach is followed, exploiting the time variation in the data at our disposal.

The meta-analysis by Evers et al. (Citation2008), which covers a range of countries, suggests that for both men and women labour supply elasticities are positive on average. This implies that both genders fall on a part of the labour supply curve where substitution effects dominate income effects, so that higher wages make work more attractive than leisure.

Despite this extensive international work, there is little focus on the influence of wage growth (in particular) on labour supply in the South African context, particularly differentiated by skill type. Instead, most authors have focused on the demographic drivers of labour force participation. It is quite likely, however, that wage increases attract otherwise non-participating individuals into the labour market (similarly to the international experience); these shifts have the potential to raise unemployment, especially if labour demand simultaneously slows down as a result of rising wages. Alternatively, if income effects dominate substitution effects, wage escalations could have a negative impact on labour force participation, although the effect may differ by household income levels. Individuals living in households with other high earners may choose to exit the labour market when their wages rise; on the other hand, if individuals live with low earners, wage growth may be an incentive to enter the labour market. Some existing evidence does suggest that individuals are unlikely to base their participation decisions on the (un)favourable labour market experiences of their own generation, but rather on those of their parents and grandparents (Rothkegel, Citation2013). Participation rates may, by inference, be only weakly related to current wage fluctuations faced by a particular peer group. However, the empirical evidence on this is limited in South Africa.

This article therefore re-examines the assertion that wage-setting is an important driver of unemployment in South Africa: it turns to micro-level estimates of employment, participation and unemployment elasticities to understand whether changes in wages of the highly paid and low-paid workers have the greatest effects at attracting individuals into the labour market and slowing down job creation.

3. Estimation strategy using micro pseudo-panel data

Usually the relationship between wage levels and employment is estimated using sector-level time-series data, with the focus on wage–employment elasticities. When this has been done in South Africa, the estimates are characteristically high and negative, indicating that rising labour costs outstrip productivity gains and, in turn, constrain employment growth (Fourie, Citation2011:53–56; Fedderke, Citation2012). This tells a particular story of the labour market, whereby the causal chain runs from labour costs to labour demand, rather than subscribing to the wage curve literature which suggests that poor labour market conditions assist in tempering wage demands.Footnote3

This narrative, however, stands in contrast to household survey evidence, which implies a relatively small role for institutionalised wage-setting (in terms of both collective bargaining and minimum wages) in reducing employment levels (Dinkelman & Ranchhod, Citation2012; Bhorat et al., Citation2013, Citation2014). By definition, the use of sectoral or firm-level data to estimate wage–employment elasticities limits the analysis to understanding issues of labour demand and how they relate to labour costs. Using household survey data will provide greater insight into how individual labour supply is related to labour costs, and in turn provides a key perspective to the unemployment puzzle.

This article therefore seeks to combine these two perspectives in estimating the influence of wages on other labour market outcomes, both on the demand and supply side, using micro-level pseudo-panel data collected from households. Household surveys contain information on individuals’ choice to enter the labour market and, following that decision, their success in being absorbed into a job. As Burger & Von Fintel (Citation2009) show, each of these outcomes contributes directly to the unemployment rate as follows:where e is the number of employed, p is the population of working age and u is the number of unemployed. These quantities can be computed for various demographic or spatial units within representative repeated cross-section household surveys over time – something which is not usually possible with macro-level time series, sectoral panel or firm panel data. Such data – aggregated for a defined spatial unit in various time periods from cross-section surveys – constitute a pseudo-panel,Footnote4 which can be treated in much the same way as a conventional panel dataset if constructed from a sufficient number of underlying data points (Verbeek & Nijman, Citation1992; Deaton & Paxon, Citation1994; Deaton, Citation1997; McKenzie, Citation2006). We use the household survey data to construct a district panel.

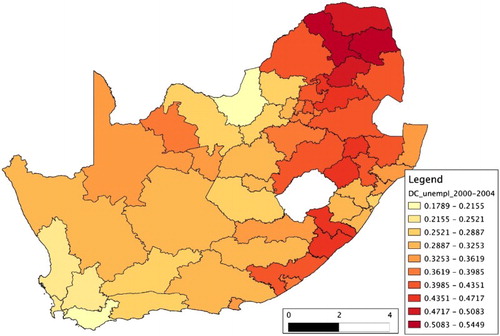

The work of Von Fintel (Citation2015) identified boundaries of South Africa’s 55 district councils as reasonable delineations of local labour markets. Hence, the labour market outcomes of all individuals that live within these spatial units are summarised and followed over time: total employment, labour force participation and unemployment as well as wage percentiles are constructed for each region. In particular, using the Labour Force Surveys (LFSs) of September 2000 through to the March 2004 round, we construct each quantity bi-annually, because it is possible to identify these demarcations in the micro data (Magruder, Citation2012). The map in shows the relevant districts, and also illustrates the distinct geographic variation in local unemployment rates across the country: labour markets are slacker in districts located in the densely populated former apartheid homelands than elsewhere. Each of these districts can be followed over time in the various rounds of the survey, allowing standard longitudinal analysis of local labour market outcomes; this is possible even if the same individuals are not sampled in each region over time but the surveys are constructed to be representative of this geographic unit.

Figure 1. District council demarcations with broad unemployment rates pooled over time.

Can conventional panel estimators be applied to these data? Typically, sampling errors may arise because the same individuals do not live in the same districts in every period. However, if the law of large numbers applies within each district in each period, then calculated statistics are immune to measurement error. We now discuss the important criteria to motivate that our panel is constructed credibly.

Firstly, district council demarcations are large enough so that substantial individual observations are sampled in each round of the LFS. While no clear criteria exist, cell sizes of 100 have been shown to be acceptable for analysis (Verbeek & Nijman, Citation1992; Verbeek, Citation2008). shows that the mean number of working-age individuals in each district exceeds 1200 in each wave of data. Fewer than 2.5% of district-time cells contain less than 100 household survey respondents. Narrowing down to working individuals, bi-annual district wage distributions, unionisation rates and firm size distributions are calculated from the responses of 436 to 493 respondents, on average.

Table 1. Characteristics of pseudo-panel data.

Secondly, the unit of analysis is stable over time. Districts are persistently represented over the survey rounds, with cell size autocorrelation above 0.98 in all instances, and demarcations remaining unaffected in this period. While it is difficult to motivate that the demarcations are chosen exogenously, Von Fintel (Citation2015) shows that district councils contain local labour markets in South Africa.

A third criterion for using standard panel estimation techniques with pseudo-panel data is ‘sufficient’ time variation (Verbeek, Citation2008). As shown by fixed effects (FE) estimations presented in and , large proportions of the error variance are accounted for by time-invariant characteristics. The empirical strategy, however, also relies on system dynamic panel models that combine information from both differences and levels to avert concerns that time de-trending has on amplifying measurement error.

Table 2. District council employment models.

Table 3. District council labour force participation and unemployment models.

The data are used to estimate the elasticity of labour market outcomes in response to wage increases at various points along the distribution. The functional forms draw from a Cobb–Douglas specification, in which all variables are logged. However, unlike theory-driven specifications that control for time-variant capital costs and output (Fedderke & Mariotti, Citation2002), data limitations entail the estimation of simpler, reduced-form functions. Despite this deficiency, household data add value in other dimensions, as already discussed. Controls for regional unobservables () and the lag of the outcome ensure that coefficients measure short-run responses (net of persistence). Common macroeconomic shocks across all districts are captured by time dummies (

). The regional working-age population is introduced to control for variation in market size across district and the potentially confounding effects of migration across time. The specification can be expressed as:

where r indexes regions and t indexes time, and y is one of total regional employment, total number of labour force participants or total number of unemployed within a district. Wage percentiles are calculated for each district at various points in the distribution, in order to establish the sensitivity of labour market outcomes to changes in wages of various types of workers (high wage and low wage). We test whether low or high wages are influential in attracting individuals into the labour market, while simultaneously placing a constraint on labour demand, thereby resulting in wage-induced unemployment.

The elasticity of interest, , is estimated along various points of the wage distribution and captures the sensitivity of labour supply and demand to rising labour costs. Because wages and outcomes are logged, the coefficient represents a percentage change in the labour market outcome, for a percentage change in the wage at a particular percentile. It can be estimated using various techniques. Ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates will be biased due to the simultaneity between wages and other labour market outcomes. Introducing district FE (as if the dataset is a usual panel) could bias estimates downwards if the measurement error that results from the aggregation process is severe. Also, this only accounts for spatial heterogeneity but does not eliminate reverse causality. On the other hand, if lagged dependent variables are included without necessary FE to capture the true data-generating process, estimates may also be downwards biased (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2009). Given these issues, we test the sensitivity of elasticity estimates to each of these identifying assumptions.

Instrumental variables may typically address the simultaneity bias, and time lags in particular (under the assumption that wages are predetermined) provide a potentially useful instrument for contemporaneous wages. We exploit multiple moment conditions in the time-lag structure of the independent variables by way of generalised method of moments (GMM) system estimators (Arrelano & Bond, Citation1991; Blundell & Bond, Citation1998). Instead of only implementing one lag as an instrument, a complex system of statistical moment restrictions between lagged variables and error terms is exploited to reduce simultaneity bias. These account for permanent regional effects and control for persistence in labour market outcomes with a dynamic specification. Verbeek (Citation2008) notes that, in the pseudo-panel context, FE estimates may be sufficient. However, as noted earlier, we also implement GMM systems estimates, which combine level and time-differenced information. This is to avoid potentially basing conclusions on measurement errors, which may dominate after de-trending that is implicit in FE estimation with persistent time series.

However, all dynamic panel data models are sensitive when the data contain a large number of time periods; the moment conditions that are imposed by GMM estimators expand multiplicatively with every extra wave of data. This results in overfitting of the endogenous variable with respect to the instrument set that is implied by the moment conditions. As a result, GMM estimates converge on OLS or FE estimates, and the risk of endogeneity re-emerges if excess instruments are included. Solutions to this problem are varied: one solution is to limit the lag length included in the instrument set; and a second approach extracts principal components from the set of lagged differenced variables (Roodman, Citation2009). We limit the lag length to an appropriate upper bound, so that the resulting number of instruments is close to the number of districts. Further limitations yield specifications that do not satisfy specification and autocorrelation tests that are necessary for consistency.

4. Results

The discussion starts with an understanding of the effects of mean wages on local labour market conditions. Following this, a set of results across the entire distribution of wages is presented graphically, but without highlighting a full set of coefficients. In this section we also explicitly consider whether behaviour is driven by the union wage premium in certain parts of the wage distribution, and – indirectly – whether bargaining council arrangements play a role.

4.1. Elasticities at the mean

Estimates of wage–employment elasticities are presented in the first row of . The pooled OLS approach in column 1 accounts for none of the potential estimation biases discussed in Section 2. The method delivers a statistically insignificant negative elasticity and contrasts somewhat with sectoral evidence, which usually finds large negative and significant elasticities.

FE estimates in specification 2 control for permanent regional heterogeneity, raising the elasticity to a larger negative and significant effect. GMM system estimates in specification 3 adjust for both regional heterogeneity and reverse causality, yielding a coefficient magnitude that aligns closely to the FE estimates. This is, however, statistically insignificant. Regardless of the identification strategy, the elasticity remains lower than those found by sectoral studies of mean wages (Fourie, Citation2011:53–56).

The GMM result is credible from a diagnostic perspective: the insignificant Hansen test statistic suggests that the moment conditions are not over-identified, so that each of the lagged instruments has an influence on reducing bias. Additionally, the pattern of significant first-order autocorrelation in the error terms and zero second-order autocorrelation conforms to the norms that are required for the consistency of the GMM estimator (Arrelano & Bond, Citation1991). All GMM specifications in this article satisfy these criteria.

Specifications 4 to 6 repeat the previous estimates, but control for district-level union density and the concentration of employment in small and large firms. These indicators proxy for wage-bargaining institutions, which occur at the firm level and in bargaining councils between large firms and large unions (Bhorat et al., Citation2012; Magruder, Citation2012). Notably, the FE coefficient halves, but remains stable and insignificant in the case of the GMM estimator. In all specifications, high union rates reduce employment levels. At least part of the effect of wages on labour demand can be accounted for by wage escalations that result from these institutions.

Specifications 7 to 9 presented in repeat these regressions, but this time considering labour force participation. All elasticities are small in magnitude, regardless of the estimation procedure; they de-emphasise the role of wages in driving the rise in labour force participation and, in turn, unemployment. Instead, it appears that income effects dominate substitution effects in labour force participation, with income gains of other household members prompting some exit from the labour market.

Specifications 10 to 12 turn to the effect of wages on unemployment, which is the outcome of both the demand and supply effects. Accounting for FE and reverse causality leads to a large positive unemployment elasticity, although results are statistically insignificant at the mean (the result differs at other points in the distribution, as discussed in the following). While we do not observe a pattern by which wage growth increases labour supply (and in turn raises unemployment), the labour demand channel dominates in contributing to unemployment.

4.2. Non-constant elasticities

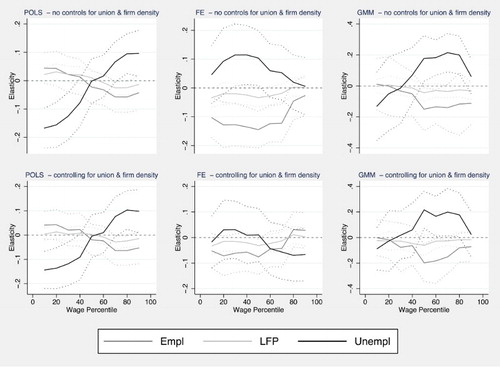

Until now the discussion has focused on mean wages. However, these estimates ignore the fact that wage increases along different points of the distribution may have heterogeneous impacts on labour market incentives. summarises the set of elasticities from various estimators. The first row of figures represents coefficients from specifications that have the same set of control variables as specifications 1 to 3 and 7 to 12, while the second row shows elasticities that additionally condition on union density and the firm size structure of districts.

Figure 2. Employment, LFP and unemployment elasticities along the wage distribution using various estimators.

Wage–employment elasticities estimated by OLS are only statistically negative for wages above the 60th percentile. In the case of FE, they are negative and significant for most of the lower part of wage distribution, while for GMM this is only true in the middle of the distribution. The introduction of union and firm size controls yields a statistically zero effect in all percentiles for FE estimates and in most percentiles for GMM estimates. These results indicate that employment reductions are particularly attributed to wage growth in districts with high union densities and with high concentrations of large firms.

Wage–participation elasticities are small and insignificant across most of the wage distribution, regardless of the estimation strategy. Demand-side effects therefore dominate in determining unemployment, regardless of whether wages of high-paid or low-paid workers change.

Finally, wage–unemployment elasticities estimated by OLS are close to –0.1 in the lower tail of the wage distribution. This reflects the standard wage curve magnitude estimated by many researchers; such an effect is dominated by changes in wages of low earners. However, as found by Von Fintel (Citation2015), accounting for regional heterogeneity with FE and reverse causality by GMM, the effect is reduced to zero at the bottom and the very top of the distribution. Unemployment responds to growth in wages at the middle of the distribution, and not for the least skilled, as time-series evidence from the 1970s–90s would suggest (Lewis, Citation2001). Again, controls for unionisation and firm sizes reduce GMM elasticities in magnitude, and in the case of FE they collapse to zero. These models emphasise that the wage growth which contributes to unemployment is in turn determined by institutional bargaining arrangements.

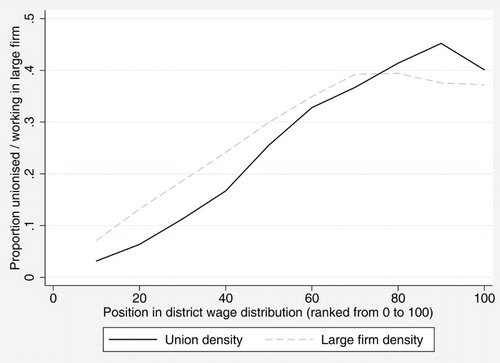

Previous evidence on wage-setting supports collective bargaining inhibiting labour demand, particularly so in small firms (Magruder, Citation2012; Rankin, Citation2016). shows both district-level union density and large-firm density (defined as a firm with more than 50 employees) along the wage distribution. While both indicators rise with wages, the steepest incline for union density is in the middle of the distribution, with a decline at the very highest end. Similarly, large-firm density rises steadily, but flattens off from the seventh wage decile. Comparing this figure with the wage elasticities, they correspond to the evolution of GMM estimates, whereby the wage–unemployment elasticity increases in a similar fashion to both unionisation and firm size density. Unionisation seems to correspond with wage increases and a larger labour demand response.

5. Conclusion

While the macroeconomic literature has emphasised labour demand as the channel through which rising labour costs fuel the level of joblessness, microeconometricians have emphasised the supply side in understanding unemployment in South Africa. This study has turned to both sides of this debate, by estimating the elasticity of various labour market outcomes to district-level wages. It confirms that primarily labour demand is affected by wages, while labour supply is not as sensitive to the allure of better remuneration for workers. This does not abstract from the important role that expanding labour supply has had in rising unemployment in South Africa. It does, however, suggest that this did not occur through increases in wages, but rather by way of other demographic changes. Wages do, however, exert substantial influence on firms’ choice to expand employment, confirming some previous results. This is particularly true for workers that are paid moderate to high wages, where various estimates do show that unemployment increases in response to their wages.

The evidence also suggests that the channel through which these changes operate includes high concentrations of unionised workers and employment in large firms (which typically bargain collectively). While this research does not claim to understand all features of high unemployment in South Africa, it does highlight how labour costs play a causal contributing factor in keeping its level elevated. The research contrasts with evidence which suggests that institutionalised wage-setting does not have uncharacteristic influences on labour demand (Bhorat et al., Citation2013, Citation2014), while it falls more closely in line with other work that highlights the role of unions and collective bargaining in inhibiting employment creation (Magruder, Citation2012; Rankin, Citation2016). This is not to say that non-unionised, low-paid workers’ wages can be raised without costs to employment; it is potentially true that once similar conditions (such as the proposed national minimum wage legislation) are applied to such workers, then similar effects could potentially manifest. These eventualities require continued rigorous investigation.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges funding for this research from the Research Project on Employment, Income Distribution and Inclusive Growth (REDI3×3). Opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of REDI3×3.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Dieter von Fintel http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6771-1315

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Wage demands can be both the outcome of and a contributor to unemployment. In the first instance, high local unemployment rates generally result in lower wage bargaining power and wage demands. In the second instance, wages that exceed the value of marginal productivity reduce labour demand.

2 Wages are commonly known to be distributed skewly, following approximately log-normal and Pareto forms. This implies that the average lies considerably below the median. This is also true in South Africa (Von Fintel, Citation2007).

3 In fact, recent research (Von Fintel, Citation2015) has questioned the existence of the short-run wage curve for South Africa: a lack of an effect of local unemployment rates on wages in micro data (in contrast to the robust relationship found between employment and wages in sectoral data) emphasises the need to separately identify the bi-directional causal chains.

4 These data are not a pure panel dataset, because they do not necessarily follow the same individuals over time. However, the data follows the aggregate outcomes of a representative group of individuals that constitutes a chosen unit of measurement – be it a birth cohort or a spatial unit. Repeated cross-sections can be aggregated in this manner to construct a pseudo-panel.

References

- Albaek, K, Asplund, R, Blomskog, S, Barth, E, Guomundsson, BR, Karlsson, V & Madsen, ES, 2000. Dimensions of the wage-unemployment relationship in the nordic countries: Wage flexibility without wage curve. In Polachek, SW (Ed.), Worker well-being – research in labour economics. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, 345–81.

- Altonji, JG & Devereux, PJ, 1999. The extent and consequences of downward nominal wage rigidity. NBER working paper 7236. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge.

- Angrist, J & Pischke, J-S, 2009. Mostly harmless econometrics – an empiricist's companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Armstrong, P & Steenkamp, J, 2008. South African trade unions: An overview for 1995 to 2005. Stellenbosch Economic Working Paper 10/08.

- Arrelano, M & Bond, S, 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58, 277–97. doi: 10.2307/2297968

- Baltagi, BH, Baskaya, YS & Hulagu, T, 2012. The Turkish wage curve: evidence from the household labor force survey. Economics Letters 114(1), 128–31. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2011.09.033

- Banerjee, A, Galiani, S, Levinsohn, J, McLaren, Z & Woolard, I, 2008. Why has unemployment risen in the New South Africa? Economics of Transition 16(4), 715–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0351.2008.00340.x

- Barattieri, A, Basu, S, & Gottschalk, P, 2014. Some evidence on the importance of sticky wages. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 6(1), 70–101.

- Behar, A, 2010. Would cheaper capital replace labour? South African Journal of Economics 78(2), 131–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2010.01240.x

- Bhorat, H & Hodge, J, 1999. Decomposing shifts in labour demand in South Africa. The South African Journal of Economics 67(3), 155–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.1999.tb01146.x

- Bhorat, H, Mayet, N & Kanbur, R, 2013. The impact of sectoral minimum wage laws on employment, wages, and hours of work in South Africa. IZA Journal of Labor and Development 2(1), 1–27. doi: 10.1186/2193-9020-2-1

- Bhorat, H, Naidoo, K & Yu, D, 2014. Trade unions in an emerging economy – the case of South Africa. WIDER Working Paper 2014/055. United Nations University – World Institute for Development Economics Research, Helsinki.

- Bhorat, H, Goga, S & van der Westhuizen, C, 2012. Institutional wage effects: Revisiting union and bargaining council wage premia in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics 80(3), 400–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2011.01306.x

- Blanchflower, DG & Oswald, AJ, 1990. The wage curve. NBER Working Paper 3181.

- Blanchflower, DG & Oswald, AJ, 2008. Wage curve. In Durlauf, SN & Blume, LE (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. 2nd edn. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online. Palgrave Macmillan. http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_W000135

- Blien, U, Dauth, W, Schank, T & Schnabel, C, 2013. The institutional context of an ‘empirical law’: The wage curve under different regimes of collective bargaining. British Journal of Industrial Relations 51(1), 59–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8543.2011.00883.x

- Blundell, R & Bond, S, 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87, 115–43. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

- Branson, N & Wittenberg, M, 2007. The measurement of employment status in South Africa using cohort analysis, 1994–2004. The South African Journal of Economics 75(2), 313–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2007.00113.x

- Burger, RP & von Fintel, DP, 2009. Determining the causes of the rising South African unemployment rate: An age, period and generational analysis. Working Paper 158. Economic Research Southern Africa, Cape Town.

- Burger, RP & von Fintel, DP, 2014. Rising unemployment in a growing economy: A business cycle, generational and life cycle persepective of post-transition South Africa's labour market. Studies in Economics and Econometrics 38(1), 35–64.

- Burger, RP, van der Berg, S & von Fintel, DP, 2015. The unintended consequences of education policies on South African participation and unemployment. South African Journal of Economics 83(1), 74–100. doi: 10.1111/saje.12049

- Casale, D & Posel, D, 2002. The continued feminisation of the labour force in South Africa: An analysis of recent data and trends. South African Journal of Economics 70(1), 156–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2002.tb00042.x

- Daouli, J, Demoussis, M, Giannakopoulos, N & Laliotis, I, 2013. The wage curve during the great depression in Greece. 8th IZA/World Bank Conference on Employment and Development, 22–23 August, Bonn, Germany.

- Deaton, A, 1997. The analysis of household surveys: A microeconometric approach to development policy. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Deaton, A & Paxon, C, 1994. Saving, growth and aging in Taiwan. In Wise, DA (Ed.), Studies in the economics of aging. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 331–62.

- Dinkelman, T & Ranchhod, V, 2012. Evidence on the impact of minimum wage laws in an informal sector: Domestic workers in South Africa. Journal of Development Economics 99(1), 27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.12.006

- Evers, M, de Mooij, R & van Vuuren, D, 2008. The wage elasticity of labour supply: A synthesis of empirical estimates. De Economist 156, 25–43. doi: 10.1007/s10645-007-9080-z

- Fedderke, J, 2012. The cost of rigidity: The case of the South African labor market. Comparative Economic Studies 54, 809–42. doi: 10.1057/ces.2012.25

- Fedderke, J & Mariotti, M, 2002. Changing labour market conditions in South Africa: A sectoral analysis of the period 1970–1997. South African Journal of Economics 70(5), 830–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2002.tb00047.x

- Fourie, FCVN, 2011. The South African unemployment debate: Three worlds, three discourses? SALDRU Working Paper 63. University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Hofmeyr, JF & Lucas, REB, 2001. The rise in union wage premiums in South Africa. Labour 15(4), 685–719. doi: 10.1111/1467-9914.00183

- Klein, N, 2012. Real wage, labor productivity, and employment trends in South Africa: A closer look. IMF Working Paper 12/92. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

- Levinsohn, J, Rankin, N, Roberts, G & Schoer, V, 2014. Wage subsidies and youth employment in South Africa: Evidence from a randomised control trial. Stellenbosch Economic Working Paper 02/14. University of Stellenbosch.

- Lewis, JD, 2001. World Bank informal discussion paper on aspects of the economy of South Africa 16.

- Magruder, J, 2012. High unemployment yet few small firms: The role of centralized bargaining in South Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(3), 138–66.

- McKenzie, D, 2006. Disentangling age, cohort and time effects in the additive model. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 68(4), 473–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.2006.00173.x

- Ranchhod, V & Finn, A, 2014. Estimating the short run effects of South Africa's employment tax incentive on youth employment probabilities using a difference-in-differences approach. SALDRU Working Paper 134. Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, Cape Town.

- Rankin, N, 2016. Labour productivity, factor intensity and labour costs in South African manufacturing. REDI3×3 Working Paper. Research Project on Employment, Income Distribution and Inclusive Growth, Cape Town.

- Roodman, D, 2009. A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 71(1), 135–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.2008.00542.x

- Rothkegel, M, 2013. Generational returns to education. Stellenbosch University, Mimeograph.

- Verbeek, M, 2008. Pseudo-panels and repeated cross-sections. In Mátyás, L & Sevestre, P (Eds.), The econometrics of panel data. Springer, Berlin, 369–83.

- Verbeek, M & Nijman, T, 1992. Can cohort data be treated as genuine panel data? Empirical Economics 17, 9–23. doi: 10.1007/BF01192471

- Von Fintel, DP, 2007. Dealing with earnings bracket responses in household surveys – how sharp are midpoint imputations? The South African Journal of Economics 75(2), 293–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2007.00122.x

- Von Fintel, DP, 2015. Wage flexibility in a high unemployment regime: Spatial heterogeneity and the size of local labour markets. REDI3×3 Working Paper 8. Research Project on Employment, Income Distribution and Inclusive Growth, Cape Town.

- Wakeford, J, 2004. The productivity–wage relationship in South Africa: An empirical investigation. Development Southern Africa 21(1), 109–32. doi: 10.1080/0376835042000181444