ABSTRACT

This research analyses the commitment to and use of ‘balanced scorecards’ by retailers in generating sustainable profitability, whilst contributing to socio-economic development in South Africa. An international literature review of scorecard frameworks, plans and reports by major retail companies and semi-structured dialogic interviews with a purposive sample of retail business stakeholders and government officials formed the methodology. By contrasting the literature and empirical insights, a summary of findings was generated, which conclude that most retailer scorecards (formal or informal) seek to balance financial with ‘cause-related marketing’ targets, but implementation differs according to factors such as company size, developmental maturity and managerial competence. Furthermore, collaboration between retailers and state institutions in scorecard management is not a reality, as has been achieved in other industries. It is therefore recommended that a Retail Charter scorecard framework be considered, to promote public/private-sector knowledge-sharing and socio-economic development.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

A review of the South African retail sector’s contribution to the socio-economic vision and developmental themes of the National Development Plan (NDP) identified that the retail supply chain can have significant socio-economic added value, with job creation and cause-related marketing implications, within the social and economic diversity of South African society (Corbishley & Mason, Citation2011; Gauteng Provincial Treasury, Citation2012; Accenture, Citation2014; Bureau of Market Research, UNISA, Citation2014; Sewell et al., Citation2014; Burger et al., Citation2015; Business Monitor International, Citation2015; National Business Initiative, Citation2015). The NDP stresses (RSA, Citation2012:27) ‘three core developmental priorities’, namely employment through economic growth, education and skills development, and development and transformation.

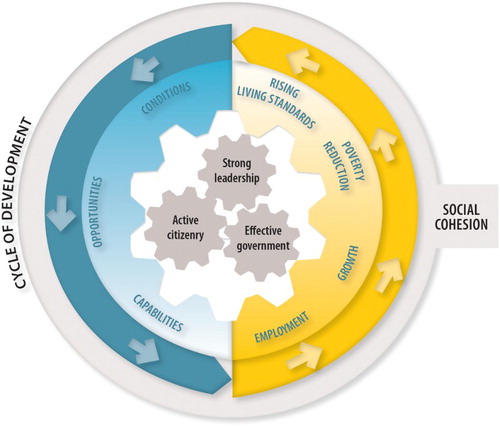

Since then, there has been ongoing debate in business and state circles regarding the ‘benchmarking’ and ‘balancing’ of collaborative roles and scorecard goals for sustainable socio-economic development (Sonnenberg & Hamann, Citation2006). This is illustrated in by the national ‘cycle of development’ performance scorecard paradigm.

Figure 1. National development plan cycle of development scorecard. Source: RSA, Citation2012:26.

1.2. Rationale for study

The dynamics of socio-economic development (Szirmai, Citation2005), studies of economic development drivers (Gveroski et al., Citation2011) and a multivariate approach in measuring socio-economic development in Middle East and North African countries (Milenkovic et al., Citation2014) have contributed significantly to the study of the problems and possibilities of developing countries. The retail sector is a significant component of the South African social economy and a major employer. Retailing is the fourth largest contributor to gross domestic product, and the 30 000 tax-registered retail enterprises employ about 22% of the economically active workforce of the country (Terblanche, Citation2016).

The social and economic transformation and equitable development that has occurred since the end of the former apartheid regime highlights the emergence of a new black middle class, motivating many retailers to reconfigure their scorecard strategies, community marketing and staffing profiles (De Bruyn & Freathy, Citation2011; Burger et al., Citation2015).

Demographic and economic developments that will continue to influence the South African retail sector, and therefore need to be included in their socio-economic development planning, include the following:

Because 65% of retail employees work for major corporates, and a national priority is to promote the entrepreneurial growth of small and medium-size enterprises, effective public/private-sector collaboration in funding and skills development is required, similar to the European Commission Retail Forum for Sustainability (2015).

The BMI (Citation2015:6) Research South Africa Retail Report suggests that household spending will remain relatively resilient, owing to a youthful, multi-ethnic and increasingly urbanised workforce, entering the middle-income bracket.

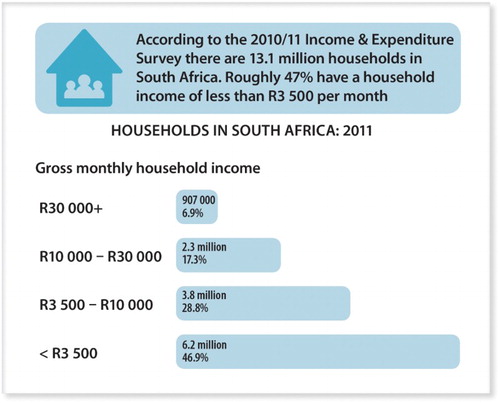

As illustrated in , gross monthly household income data reflect the inherent disparities of South African communities and consumers, which limit the financial scorecard growth potential of many retailers.

Figure 2. Gross monthly household income. Source: Statistics SA, Citation2012:10.

Rapid urbanisation is another significant factor in South Africa’s demographic landscape and developmental scorecard. The NDP (RSA, Citation2012:284) predicts that by 2030 more than 70% of South Africa’s population will live and seek employment in urban areas, moving increasingly towards mall-based retailing; a trend which is generating negative implications for the competitive sustainability of informal traders (City of Cape Town, Citation2015) and the sustainable employment creation potential of emerging retailers.

Business managers are frequently faced with decisions of how to allocate scarce resources, in an environment that is placing more and more pressures on them (Waddock & Graves, Citation1997), especially to ‘balance’ immediate financial objectives with the longer-term vision of sustainable socio-economic developmental strategies.

Business collaboration with state governance policies is not a new phenomenon, as has been evident in East Asian and European Union developmental initiatives. Business Unity South Africa (BUSA, Citation2014) has been active in promoting sector collaboration, corporate social investment and industry transformation charters, including the Mining Industry Growth, Development and Employment Task Team Report (Citation2015). No collaboration or transformation charter currently exists in the retail sector. The NDP themes include few objectives relating directly to the retail sector, although they do highlight ‘Business Drivers of Change’ (RSA, Citation2012:152), which require well-informed data and organisational scorecard synergy by retail strategists and decision-makers. It is therefore envisaged that this study will contribute to shared retail scorecard understanding, collaborative performance indicator design and focused implementation of developmental scorecards.

1.3. Objectives

The objectives of this study, therefore, are to review and analyse retail business performance indicators, based on the motivations, benefits and pressures in the strategic planning and monitoring of organisational scorecards, when short-term financial targets need to be ‘balanced’ with longer-term ‘cycle of development’ programmes and consumer marketing needs (Biggart et al., Citation2010). In terms of the national developmental priorities already highlighted, this study seeks to address the following questions through international and local literature, complemented by empirical interview insights and stakeholder perceptions into effective retail business scorecard design and management:

To what extent is a form of ‘balanced scorecard’ management system used by South African retailers as their financial and socio-economic developmental indicator?

What are the key pressures and opportunities for retail businesses to address socio-economic developmental strategies, as organisational performance indicators?

Is there evidence of benefits in the collaborative use of scorecards, between retail businesses and state institutions, to promote socio-economic development?

2. Literature review

As Szirmai (Citation2005) and Dastjerdi & Isfahani (Citation2011) highlight, the central issue in socio-economic development lies in low levels of per-capita income and low standards of living among the mass of the population in so-called developing countries. It needs to be noted that the concept of socio-economic development involves a wide range of changes in social indicators such as health, education, technology and life expectancy, which are directly or indirectly linked to economic opportunity and equity.

Literature sources were reviewed to identify the origins of the ‘balanced scorecard’ and similar multi-pronged strategic performance management systems; to explore their application by international and South African retail businesses in addressing social and economic constraints and opportunities for sustainability and/or transformation; and to analyse relevant data and insights which will contribute to answering the research questions

2.1. Origins of ‘balanced scorecards’

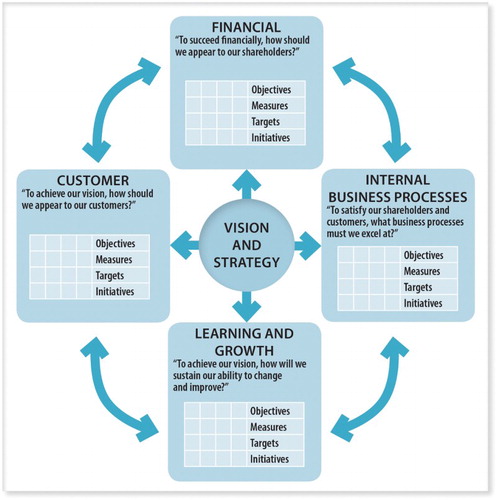

Kaplan & Norton (Citation1996) found that most organisations were not effectively aligning performance indicators, outcomes and stakeholder reports to strategic business processes Their work with a number of US companies (including a clothing retailer, a retail bank and a petroleum retailer) saw the ‘balanced scorecard’ evolve into a ‘core strategic management system’. They detailed the four ‘strategic perspectives’ which characterise the integrated ‘balanced scorecard’ performance framework as shown in .

Figure 3. The balanced scorecard strategic framework. Source: Kaplan & Norton, Citation1996:76.

Ten years later, Kaplan & Norton (Citation2006) described how successful enterprises achieve scorecard synergies by explicitly defining management’s role in aligning, coordinating and overseeing organisational strategy.

At about the same time, Elkington’s (Citation1997) ‘Triple Bottom Line’ scorecard concept measured organisational performance and sustainability indicators on three interlinked fronts:

profit: the economic value created by the company;

people: social responsibility, through fair and equitable business practices; and

planet: the use of sustainable environmental practices.

Adams (Citation2015) sets out the case for ‘integrated reporting’ and its potential to change the thinking of business managers, leading to the further integration of sustainability indicators. She refers to the increasing influence of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), a global coalition of businesses, investors, government agencies and regulators. The IIRC recommends that all ‘integrated scorecard reports’ should include a combination of quantitative and qualitative information, based on a ‘six capitals’ strategic framework of values and outputs that are transformed by the activities of an organisation – namely:

financial;

manufactured;

intellectual;

human;

social and relationship; and

natural capital.

2.2. International retailers’ scorecard practices

Benchmark examples from several countries illustrate scorecard approaches typically focused on retail investors, target customers, staff or communities in which the company seeks to promote its reputation and so enhance its ‘return on expectations’.

2.2.1. USA

Thomas et al. (Citation1999) illustrate scorecard evaluation studies in the USA, using multiple indicators of retail profitability, reputation and customer loyalty. The National Retail Federation is ‘strategically focused on jobs, innovation and consumer value’. The NRF (Citation2014:11) Annual Report highlights that member companies and National Retail Federation policy committees ‘educate lawmakers’, participating in legislature working groups which monitor employment law, health and employee benefits, food and product safety, food supply chain and postal services. Regular interaction and advocacy with government and socio-economic agencies is promoted, using the Retail Opportunity Index to ‘measure the support of policies that contribute to a healthy retail sector and US economy’ (NRF, Citation2014:15).

2.2.2. Australia

Similarly, the Retail Council in Australia is active on behalf of its members. The Council engaged with government and other industry associations at the Australian National Reform Summit in 2015, seeking common scorecards for economic and social reform, including the Indigenous Australia Program (Citation2015), a national racial equity development campaign.

2.2.3. United Kingdom

In the context of ‘balanced’, ‘triple bottom line’ and ‘six capitals’ scorecard strategies, corporate social investment and cause-related marketing indicators are also evident in British retail performance management scorecards. The Marks and Spencer Group Strategic Report (Citation2015) provides financial and non-financial performance indicators. M&S socio-economic scorecard indicators include: ‘improved product sustainability’ and ‘reduced greenhouse gas emissions impact’, both of which require effective product sourcing and supply chain management.

2.2.4. Conclusion

These international retail performance scorecard benchmarks illustrate a range of management practices to ‘balance’ the traditional ‘bottom line’ financial success indicator with socio-economic developmental goals, typically seeking to promote community awareness and consumer loyalty, towards business sustainability and growth.

2.3. Scorecard practices of South African retailers

2.3.1. Socio-economic development applications

Besides consideration of the National Development Plan: Vision 2030 (RSA, Citation2012), the literature review covered national socio-economic developmental analyses, including topics relating to socially responsible business investment in South Africa such as Bureau for Economic Research/Ernst & Young's (Citation2015) Retail Survey and Business Monitor International's (Citation2015) South African Retail report, which provide insights into developmental scorecard perceptions, pressures, problems, opportunities and benefits.

Few academic papers relating to South African ‘balanced scorecard’ governance, regulatory and marketing strategies were evident. These included marketing and consumer behaviour in the eThekweni municipality (Corbishley & Mason, Citation2011). Regulatory framework factors which may promote, impede or pressurise sustainable business growth, socio-economic inclusivity and job creation, were found to include the following:

Entrepreneurship, youth unemployment and job market entry (African Frontiers Forum, Citation2013; South African Board for People Practices, Citation2015).

Franchising models, business reputations and community trust (Falala, Citation2013).

Other sources of relevance to socio-economic development and promoting sustainable retail business include Hamann & Acutt (Citation2003), National Labour & Economic Development Institute (Citation2007), National Economic Development and Labour Council (Citation2010), Matola (Citation2014) and Consumer Goods Council of South Africa's (Citation2015) Annual Report.

2.3.2. Examples of South African retailer scorecard practices

In the context of South Africa’s socio-economic growth and employment equity priorities and of the international retailer scorecard indicators already benchmarked, a purposive sample of annual reports of major South African retail groups was reviewed, in order to analyse their scorecard strategies and ‘cause-related marketing’ approaches to financial and socio-economic development indicators. Of the 11 major retail chains analysed, eight made use of the IIRC’s six capitals approach.

Two national retailer scorecard approaches are summarised in the following to exemplify such corporate retailers’ strategic developmental approaches.

2.3.2.1. Clicks Group Limited

The Clicks Group retail brands have a combined footprint of 657 stores; including 34 in neighbouring countries. The Clicks Group Integrated Report (Citation2015) states that the IIRC scorecard framework has been adopted. Performance against 2015 objectives and plans for 2016 are detailed for each retail brand, within the six ‘scorecard capitals’; and material issues, risks and opportunities are defined with financial and reputation implications. Socio-economic performance scorecard indicators are reviewed, including transformation targets in terms of the United Nations Global Compact. The projects highlighted were undertaken by the Clicks Foundation, Clicks Helping Hand Trust, bursary and internship programmes for pharmacy students and the black empowerment and transformation strategy, to maintain progress in ownership, management, skills development and socio-economic development.

2.3.2.2. Woolworths Holdings Limited

The Woolworths Holdings Integrated Report (Citation2015) defines this major retail group’s business model and scorecard as based on the IIRC six capitals framework, noting that this framework has introduced the concept of how a business creates value through the use of financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural capital.

Woolworths Holdings highlights the core scorecard value of ‘sustainability’ in its ‘Good Business Journey’ concept, which has earned it the accolade of South Africa’s Most Reputable Company, in terms of a national survey. The ‘Good Business Journey’ scorecard is based on effective stakeholder developmental engagement, with government and regulators, business partners, shareholders and investors, media, competitors, unions, industry bodies and customers and communities.

2.4. Key pressures and opportunities to address socio-economic development

Dastjerdi & Isfahani (Citation2011) and Taylor (Citation2015) explore the organisational and individual complexities of performance motivation, particularly related to indicators of social equity and economic growth. Apart from transformative regulations related to employment equity levels, skills development levies and preferential state procurement policies, no South African literature indicating explicit pressures or motivations was identified.

Opportunities for strengthening retail brand image and reputation or customer loyalty, based on socio-economic development and cause-related marketing programmes, are reflected, in an ‘uBuntu’ (‘Community’) brand recognition research survey of South African consumers (BrandMapp, Citation2015).

2.5. Benefits of collaborative use of scorecards

Few instances were noted in the literature of institutional collaboration in the use of retail scorecards, either between businesses or with state institutions, other than the required submission of transformation data such as employment equity and preferential procurement ratios. By contrast, the South African Mining Industry sector has collaborated in defining a scorecard for the ‘Broad-based socio-economic empowerment Charter for the SA Mining Industry’ (RSA, Citation2004). This sector collaborative scorecard was designed to facilitate the application of the Mining and Minerals Industry Socio-economic Empowerment Charter; and includes several performance indicators, ranging from human resource development and employment equity, to beneficiation and reporting.

Strategic plans and reports of certain business organisations indicate their commitment to membership information sharing, around socio-economic transformation goals and achievements, within the defined vision of the NDP. Examples of organisations with retail business membership include the following:

The SA Retail Council; whose stated objective is to deal with ‘issues facing the retail sector in two particular areas being the economic and legislative affairs and labour relations’ (Consumer Goods Council of South Africa, Citation2010:1).

The National Business Initiative (Citation2015:4); which states that …‘collective action between business, government and society supports large scale positive and systainable systemic change’.

The Black Management Forum; which includes several retail members. A recent Black Management Forum press release reflected its main purpose of influencing socio-economic transformation, in pursuit of justice, fairness and equity.

Findings of the Quality of Life Survey: City Benchmarking Report (GCRO, Citation2013), Position Paper on Employment Equity (South African Board for People Practices, Citation2015) and SA Reconciliation Barometer 2015 (Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, Citation2016) underscore the need for retailers to:

address the differing expectations of ethnic and generation groups, across the country’s socio-economic inequality levels; and

demonstrate their commitment to promoting developmental progress, towards a more equitable society.

3. Methodology

A qualitative research methodology was used for this formative evaluation study, following a data-gathering and analytical approach (Emmel, Citation2013). The literature review phase sought to strengthen understanding of the international retail business contexts of the ‘Triple Bottom Line’ (Elkington, Citation1997) and ‘Balanced Scorecard’ (Kaplan & Norton, Citation1996) performance management paradigms. Thereafter, dialogic interviews with retail stakeholders sought to gain insights into the evolving perceptions of the sector’s socio-economic development strategies. In the process, it became evident that a qualitative focus on the retail customer profiles, supply chains, employee engagement and community demographics would be needed to answer the research questions, within a relational social capital framework.

The interview guide, based on the relevant literature, was designed to identify the use by retail organisations of a ‘balanced scorecard’, ‘triple bottom line’ or similar integrated performance strategy framework, aligned with national development priority themes; and to analyse possible retail sector strategy variances.

Based on the interview guide, dialogic interviews were held to gain insights into retailer socio-economic development priorities. A purposive sample of 60 retail business and regulatory stakeholders in major urban regions was selected, as presented in . Interviews were held individually or in small groups, with responses being recorded manually on the interview guide ‘questionnaires’. Prior to data collection, the study was approved by the CPUT Ethics Committee (Certificate No 2015FBREC328) and all respondents received a letter of information and informed consent.

Table 1. Sample profile.

Because of the qualitative nature of the study, the data collected were analysed manually, using frequency statistics and content analysis using MS Word and MS Excel. In order to summarise the opinions of the large number (n = 60) of respondents, responses were deconstructed and then reconstructed according to themes (Lee, Citation1999). These themes involved retail management use of a ‘balanced scorecard’, or similar performance management tool, for synergising short-term financial objectives with longer-term community and/or socio-economic investment goals, in support of employment, development, equity and sustainability strategies. The reconstructed findings were then used to answer the research questions presented in Section 1.3.

Face and context validity of the data collection instrument was tested with retail and research experts, and the instrument was then pilot tested with a small sample of retail stakeholders and regulatory role-players. Overall trustworthiness of the findings comes from the spread of different types of respondents (see ) and from a peer-review critique of the draft paper, provided by a focus group of retailer and retail association representatives. Their feedback enhanced validity and trustworthiness of this study. Therefore, the findings are generally believed to be credible and trustworthy because of source triangulation (respondent categories) and peer debriefing (checking of results with a focus group made up of industry experts and retailer representatives) (Padgett, Citation1998).

4. Findings from interviews

In order to supplement the retail scorecard data from the literature insights, perceptions and data relevant to the research questions are now summarised.

4.1. Knowledge and awareness of performance scorecards

The interviews indicated that knowledge of literature regarding organisational performance scorecards varied, according to the management role, organisational size, complexity and performance measurement culture:

High ‘balanced scorecard’ and ‘triple bottom line scorecard’ awareness and usage was most evident (70%) amongst retail corporate and franchise owner/management; as well as most sector consultants, with relevant business management education.

Low ‘balanced scorecard’ awareness was evident amongst most small and medium sized enterprises (SME) owner/managers (10%); although several recognised the operational value of defining their financial and community reputation goals, to motivate staff and measure success.

4.2. Use of balanced scorecards

The extent of ‘balanced scorecard’ performance management use by South African retail organisations varies considerably. Overall, 90% of respondents were aware of ‘performance scorecard targets’ in their organisations, although these were usually financial ‘bottom line’ targets for the branch, department or individual manager.

After clarification (‘aided recall’) of the concept of a ‘balanced’ or ‘multi-pronged’ framework of integrated business scorecard targets, including community development objectives, the extent of such scorecard usage was evident, as presented and illustrated by typical commentary in .

Table 2. Aided awareness of scorecard usage.

4.3. Pressures, opportunities and problems regarding socio-economic development

This research question elicited a diverse range of stakeholder responses and motivations, based largely on their business size, organisational maturity, product sub-sector and personal perception of the private sector’s role in South Africa’s socio-economic transformation. Perceptions of organisational key performance areas for socio-economic development were typically based on the following criteria.

4.3.1. Pressures

4.3.1.1. Broad-based black employment equity

The most frequently mentioned ‘pressure’ was that of broad-based black employment equity levels, often perceived to be a mandatory requirement for business licensing and growth opportunity, subject to Department of Labour assessments.

4.3.1.2. Regulatory bureaucracy

Concerns were also expressed about other potential state bureaucracy or further regulatory requirements, which would restrict business entrepreneurship and autonomy.

4.3.1.3. Staff transformation

Less formally, but no less perceived as reality, was the requirement to be seen as transforming staff complements – especially in communities where the emerging black middle class represents a significant consumer ‘pressure group’.

4.3.2. Opportunities

Across the spectrum of retail enterprise size and maturity, most respondents indicated an ongoing alertness to cost-effective opportunities to align their product mix, sales and corporate social investment activities with community profiles and developmental projects. For example, programmes to promote healthy eating (by supermarkets) and moderate drinking (by liquor retailers) were cited; as were cause-related marketing programmes by schoolwear and stationery suppliers, and by an optician/eyewear retailer to the ‘OneSight’ eye testing support programme.

4.3.3. Problems

The most frequently cited problems relating to implementing meaningful socio-economic development strategies in retail business performance scorecards were as follows:

‘copy cat’ competition when less innovative retailers in the same sub-sector ‘steal’ promotional ideas, diffuse the project identity and reduce the community impact of the initiative; and

time and additional costs of promoting such community developmental strategies, especially when the inputs (such as education or healthcare promotion) are seen to be the accountability of a ‘capable state’ and not a role for the business sector.

4.4. Benefits of collaborative use of balanced scorecards by business and state

Empirical analysis of stakeholder comments regarding the ranking of NDP ‘core priorities of socio-economic development’, and of answers to the question relating to benefits which have motivated use of a ‘multi-pronged scorecard’, indicates that the following:

Inter-departmental and/or inter-branch collaboration is often enhanced by the shared use of an organisational scorecard. Ninety per cent of corporate retail business respondents confirmed this benefit, especially when company-wide awareness of socio-economic development projects was created by mutual scorecard use, with regular feedback reports and recognition of efforts and achievements, through company media.

Collaborative socio-economic scorecard use between retail businesses is evident in several retail sector associations where shared sector benefits are the motivation. Illustrative examples include the following:

petroleum retailers – collaborative promotion of workplace health and safety campaigns, aligned with legislation;

clothing retailers – encouragement of local textile supplier development; and

South African Small and Medium Enterprise Federation members – collaborative supply chain partnerships and workshops, to develop project management skills.

The caution was frequently expressed, however, that such collaboration is focused on community profiling and socio-economic development projects; and not on business financial goals, which would be undesirable, if interpreted as ‘collusion’ or ‘anti-competitive’:

(c) Collaborative scorecard programmes between retail business and state institutions are evidently unusual, except where an NDP ‘core priority’ is ranked highly by the retail business sector. In this regard, near unanimity of NDP importance ranking by retail stakeholders is presented in .

Table 3. Ranking of NDP priorities by retailer stakeholders.

Examples of such private/public scorecard collaboration benefits, as identified by retail sector interviewees, include the following:

Clothing retailers – joint planning with Department of Trade and Industry to promote capacity-building of local textiles manufacturers (‘important for developmental job creation, cost reduction and new customers’).

Retail banking – collaboration with the National Student Financial Aid Scheme, to promote bursaries and financial support for deserving university and college students (‘we must overcome the lack of mutual trust and understanding, if we want to build a stable future’).

4.5. Differentiation of scorecard perspectives by size and sub-sector

Company size and sub-sectors certainly generate significant differences in the focus and complexity of enterprise scorecard perspectives, socio-economic developmental strategies and business outcomes, evidenced by responses to the following interview questions.

4.5.1. Use of a ‘multi-pronged scorecard’ framework for measuring retail performance

Company size, organisational performance, culture and maturity were certainly the defining factors in the responses to this question:

Always (60%): major corporates have typically built ‘multi-pronged scorecard’ awareness and action into their organisations, down to branch level (‘It’s a normal part of our business planning’).

Sometimes (20%): aspirant corporates, often led by young, high-calibre executives, had introduced a form of multi-pronged scorecard – focused on building their profile and profitability in the target community (‘We want to be seen to be doing the right things’).

Never (20%): SMEs and informal traders, inexperienced or in survival mode, seldom have a formal business scorecard, although their community profiles are neighbourly and a daily activity (‘Smaller retailers can’t take on this additional burden’).

4.5.2. Socio-economic development strategies as part of all retail scorecards

Seventy-five per cent of stakeholders responded that all retailers should include some sort of socio-economic transformation goals, to help build their customers and the country; but they recognised that SMEs and historically disadvantaged traders often do not have the necessary time, capacity or marketing skills to do so.

‘We need to work together, for collective growth and success’ was how a group of township traders expressed their need for a shared scorecard system.

4.5.3. Readiness to collaborate in a national retail sector charter

Respondents were asked to rank their readiness on a three-point scale: 1 = ‘Yes, ready for a Retail Sector Charter’; 2 = ‘Not sure: Need time to consider’; and 3 = ‘No, we see no value in this idea’.

Again, company and retail sub-sector size and collaborative market culture were significant indicators for typical responses to this question:

Yes (40%): although only a few respondents (mainly well-established corporates) were confident that participation in developing an industry-wide Retail Charter would add developmental value, their confidence was based on successful collaboration in business fora, such as the Business Unity South Africa or National Business Initiative, or associations such as the Retail Motor Industry Organisation, Consumer Goods Council and National Clothing Retailers Federation.

Not sure (50%): most respondents indicated concerns regarding the value-added potential of participation, sometimes based on mistrust of state regulations and/or competitors. Typically, they asked for more detail on the proposed goals and regulatory authority of such a Retail Charter.

No (10%): the time commitment and regulatory suspicion factor, alluded to earlier, caused these respondents to deny any value in participation in a Retail Sector Charter forum. When the possibility of representation through the South African Small and Medium Enterprises Federation, Business Unity South Africa or retail sector associations was mooted, several respondents then indicated a readiness to debate the process further.

4.6. Summary of findings

The findings for the empirical component of this analysis of ‘balanced scorecard’ socio-economic developmental management strategies by South African retailers reflect the following:

Most of the larger retail corporates are aware of a balanced scorecard approach as a performance indicator to measure success, while smaller retail businesses focus on financial performance but do recognise the operational value of goals to improve reputation in the community.

Financial targets are dominant; and where there are other indicators, such as transformation and community projects, managers do not always communicate these to their staff. It is rather done to boost the external image of the business.

The main problem which retailers experience in broadening their scorecard from purely financial indicators is the time needed and the additional cost, as well as the risk of competitors copying their strategies.

Most collaboration between businesses on social development issues is on a sector/industry level; business leaders prefer to do it through sector associations, to prevent accusations of collusion.

There is little evidence of collaboration or knowledge-sharing between businesses and governmental institutions on socio-economic developmental issues.

In summary, South African retail businesses are pragmatically aware of the need to be contributing to local or regional socio-economic development projects, but with significant variances in scorecard design, effective implementation and sector collaboration.

In the next section, joint conclusions from the literature review and the empirical study will be summarised, within the framework of the research questions.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

Reflecting on the research questions, available evidence, qualitative data and insights gained from the literature review and empirical interviews, a comparative analysis of findings is summarised in .

Table 4. Overall summary of findings.

In response to each of the research questions, the table indicates ratings of high, medium or low evidence value relative to the questions; and congruence ratings of findings from the literature review and the empirical interviews, as an evidenced-based framework for conclusions and recommendations. The congruence ratings in the summary are based on interviewee awareness or endorsement of literature review factors.

Based on these ratings of congruence between literature review and stakeholder interview findings with regard to the research questions, the following is concluded:

Forms of ‘balanced scorecard’ management systems are strategically used by retail corporates, with a clear cause-related marketing approach in annual reports. Many smaller enterprises also use informal scorecards to focus and motivate staff in planning and monitoring financial targets and community reputation projects.

Significant pressures and opportunities for socio-economic development scorecard initiatives are typically based on the competitive nature of retailing, when reputations and customer loyalty are energised by the visibility and frequency of socio-economic development projects.

Little evidence is available for collaborative use of balanced scorecards, especially in private/public partnerships. Retailers who have benefitted from collaboration within retail groups or trade associations are more open to exploring business/state ‘active citizenry’ information-sharing and developmental collaboration.

5.2. Implications for the retail sector

Because there are perceived benefits to collaboration on socio-economic issues, we recommend that retailers consider two approaches to working collaboratively.

5.2.1. Retail stakeholder forum

Given the broad stakeholder recognition of the pragmatic value of a business performance scorecard, even when informally conceptualised, the wide variances in implementation of ‘balanced’ or ‘integrated’ scorecards with socio-economic developmental indicators, and consequent reservations about readiness to collaborate, it is recommended that a retail stakeholder forum should be convened, to consider the potential value of a ‘national retail sector developmental scorecard’, as a framework for further collaborative research, nationally and regionally.

5.2.2. Retail charter scorecard indicators for collaborative adoption

It is further recommended that the Wholesale & Retail Leadership Chair provides informative input to such a stakeholder forum. Two examples of scorecard indicators that could be considered the basis for a retail charter/scorecard are the Broad-based Socio-Economic Charter for the Mining Industry (RSA, Citation2004) and the IIRC (Adams, Citation2015) ‘six capitals of value creation’ framework, as already in use by several South African retailers.

5.3. Recommendations for further research

In addition to the advocacy actions recommended, it is also suggested that further research into the topic is needed to increase shared understanding of retail’s potential role in socio-economic development. The following are recommended:

Socio-economic developmental needs that could be best addressed by retailers.

What are retailers doing at regional and local levels, to address the socio-economic developmental needs of their communities?

What could the sector do to expand such activities on a national basis?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Accenture. 2014. The secret of seamless retailing success. www.accenture.com/Microsites/retail-research/Pages/consumer-research-results. Accessed 24 April 2014.

- Adams, C, 2015. Understanding integrated reporting. Greenleaf Publishing, Saltaire, UK.

- African Frontiers Forum, 2013. Africa’s youth and the unemployment challenge – The impact on Africa’s economic outlook. Paper Delivered at the African Frontiers Forum Conference, 15 May 2013, Johannesburg. www.frontieradvisory.com. Accessed 8 January 2014.

- Biggart, B, Burney, L, Flanagan, R & Harden, J, 2010. Is a balanced scorecard useful in a competitive retail environment? Management Accounting Quarterly 12(1), 1–12.

- BrandMapp, 2015. The uBuntu report. Whyfive, Cape Town.

- Bureau for Economic Research/Ernst & Young, 2015. Retail survey. Ernst & Young, Johannesburg.

- Bureau of Market Research, 2014. Retail trade sales forecast for South Africa, 2014. Research Report Number 443. BMR, University of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Burger, R, Louw, M, Pegado, B & Van der Berg, S, 2015. Understanding consumption patterns of the established and emerging South African black middle class. Development Southern Africa 32(1), 41–56. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2014.976855

- BMI (Business Monitor International), 2015. South Africa Retail Report 2015. www.bmiresearch.com Accessed 30 December 2015.

- BUSA (Business Unity South Africa), 2014. Annual review: One voice of business. BUSA, Sandton.

- City of Cape Town, 2015. Economic development strategy. www.capetown.gov.za Accessed 27 November 2015.

- Clicks Group Integrated Report, 2015. Clicks Group Limited, Cape Town.

- Consumer Goods Council of South Africa, 2010. South African Retail Council launched. iFashion, 28 April. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:AH9CB0MEJv8J:www.ifashion.co.za/index.php%3Foption%3Dcom_content%26amp%3Bview%3Darticle%26amp%3Bid%3D2702%26amp%3Bcatid%3D139+&cd=2&hl=en&ct=clnk&client=firefox-b. Accessed 31 March 2017.

- Consumer Goods Council of South Africa, 2015. Annual report. CGCSA, Johannesburg.

- Corbishley, KM & Mason, RB, 2011. Cause-related marketing and consumer behaviour in the greater eThekweni area. African Journal of Business Management 5(17), 7232–9. doi: 10.5897/AJBM10.617

- Dastjerdi, RB & Isfahani, RD, 2011. Equity and economic growth, a theoretical and empirical study: MENA zone. Economic Modelling 28, 694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2010.05.012

- De Bruyn, P & Freathy, P, 2011. Retailing in post-apartheid South Africa: The strategic positioning of boardmans. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 39(7), 538–44. doi: 10.1108/09590551111144914

- Elkington, J, 1997. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Capstone Publishing, Oxford.

- Emmel, N, 2013. Sampling and choosing cases in qualitative research – A realist approach. SAGE Publications, London.

- European Union Commission Retail Forum for Sustainability, 2013. Announcement – 15th Meeting of the Retail Forum for Sustainability. www.ec.europa.eu/environment/industry/retail Accessed 14 April 2014.

- Falala, S, 2013. Top companies reputation index: Always there for you: This retail chain exemplifies how reputations are built, in the corporate world. Mail & Guardian, 22-27 March, p. 36.

- Gauteng Provincial Treasury, 2012. The retail industry on the rise in South Africa. Quarterly bulletin, June. Provincial Treasury Economic Analysis Unit, Johannesburg.

- GCRO (Gauteng City-Region Observatory), 2013. Quality of life survey 2013: City benchmarking report. GCRO, Johannesburg.

- Gveroski, M, Risteska, A & Dimeski, S, 2011. Small and medium enterprises – Economic development drivers. Management 59, 86–94.

- Hamann, R & Acutt, N, 2003. How should civil society (and the government) respond to ‘corporate social responsibility’? A critique of business motivations and the potential for partnerships. Development Southern Africa 20(2), 255–70. doi: 10.1080/03768350302956

- Indigenous Australia Program, 2015. Australian human rights commission, Annual Report.

- Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, 2016. SA Reconciliation Barometer 2015.

- Kaplan, R & Norton, D, 1996. The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

- Kaplan, R & Norton, D, 2006. Alignment: Using the balanced score card to create corporate synergies. Harvard Business School Press, Brighton, MA.

- Lee, TW, 1999. Using qualitative methods in organizational research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Marks and Spencer Group Strategic Report, 2015. Marks and Spencer Group, London UK.

- Matola, M, 2014. NDP is a blueprint for citizens to rally round proactively. Business Report 11. July. p. 16.

- Milenkovic, N, Vukmirovic, J, Bulajic, M & Radojicic, Z, 2014. A multivariate approach in measuring socio-economic development of MENA countries. Economic Modelling 38, 604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2014.02.011

- Mining Industry Growth, Development and Employment Task Team Report, 2015. Chamber of mines of South Africa: Integrated annual review.

- National Business Initiative, 2015. Integrated annual report 2014/15. NBI, Johannesburg.

- National Economic Development and Labour Council, 2010. National retail sector strategy. Prepared for the NEDLAC trade and industry chamber, on behalf of the fund for research into industrial development, growth and equity. Silimela Development Services, Cape Town.

- National Labour & Economic Development Institute, 2007. The retail sector: An analysis of its contribution to economic growth, employment and poverty reduction in South Africa. Commissioned by the department of trade and industry, economic research and policy co-ordination unit. NALEDI, Johannesburg.

- NRF (National Retail Federation), 2014. The economic impact of the U.S. Retail Industry. Washington, DC. www.retailmeansjobs.com Accessed 16 December 2015.

- Padgett, DK, 1998. Qualitative methods in social work research: Challenges and rewards. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- RSA (Republic of South Africa), 2004. Scorecard for the broad based socio-economic empowerment charter for the South African mining industry. Government gazette notice 1639. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- RSA (Republic of South Africa), 2012. National development plan; vision 2030. National Planning Commission, The Presidency, Pretoria.

- Sewell, W, Mason, RB & Venter, P, 2014. Strategic alignment of the South African retail sector with The National Development Plan. Journal of Governance and Regulation 3(2), 235–51.

- Sonnenberg, D & Hamann, R, 2006. The JSE socially responsible investment index and the state of sustainability reporting in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 23(2), 305–20. doi: 10.1080/03768350600707942

- South African Board for People Practices. 2015. Updated position paper on employment equity and transformation. SABPP, Johannesburg.

- Statistics SA, 2012. Income and expenditure of households 2010/2011: Statistical release P0100. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Szirmai, A, 2005. The dynamics of socio-economic development: An introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Taylor, BM, 2015. The hierarchical model of motivation: A Lens for viewing the complexities of motivation. Performance Improvement 54(4), 36–42. doi: 10.1002/pfi.21475

- Terblanche, N, 2016. Retail management: A South African perspective. 2nd edn. Oxford University Press Southern Africa, Cape Town.

- Thomas, R, Gable, M & Dickinson, R, 1999. An application of the balanced scorecard in retailing. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 9(1), 41–67. doi: 10.1080/095939699342679

- Waddock, S & Graves, S, 1997. The corporate social performance – Financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal 18(4), 303–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199704)18:4<303::AID-SMJ869>3.0.CO;2-G

- Woolworths Holdings Integrated Report, 2015. Woolworths Holdings Limited. Cape Town.