ABSTRACT

Based on the competing theories regarding the relationship between family structure and child health outcomes, this article examined the effects of polygynous family system (PFS) on under-five mortality (U5M) across different socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts in selected sub-Saharan African countries. Cox proportional regression analysis was performed on pooled data of children (n = 54 842) born in the five years before the Demographic and Health Surveys of selected countries. Results indicated differential effects of PFS on U5M across varying contexts, because risks of U5M were significantly higher for children of polygynous mothers in poor communities (hazard ratio: 2.98, 95% confidence interval: 2.23 to 3.95, p < 0.001) and children of monogamists in poor communities (hazard ratio: 2.24, 95% confidence interval: 1.69 to 2.98, p < 0.001) compared with the children of monogamists in rich communities. Given the worsening effects of polygyny on childhood survival across different contexts, this study stressed the need for marriage reforms and enforcement of a monogamous family system if significant U5M reduction would be achieved in sub-Saharan African countries during the post-2015 development era.

1. Introduction

Polygyny – a union of one man and many wives – has been regarded as one of the characteristic features of sub-Saharan Africa (Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014). Although the practice of polygyny is waning across Africa, due to modernisation and westernisation, it still remains a common practice in many countries across sub-Saharan Africa. Based on findings from Westoff (Citation2003) and Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli (Citation2014), polygynous marriage is most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, with the percentage of women in polygynous unions ranging from 4% in Madagascar to 55% in Burkina Faso and 57% in Guinea. These findings indicate that, in more than a decade (i.e. 2003–14), a polygynous family system remains common practice across sub-Saharan Africa, and particularly in the West African countries.

Anthropological evidence shows that people of different socio-economic strata and background characteristics practise polygyny across sub-Saharan Africa (Gyimah, Citation2009; Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014). This suggests that Christians, Muslims and adherents of other religious faiths practise polygyny. The educated and uneducated alike practise polygyny. The phenomenon is practised in urban and rural settings. In addition, the rich and the poor practise polygyny. Available evidence has also revealed that a polygynous family system often leads to depressing capital stock and poor output as a result of low incentives to save (Sear et al., Citation2002; Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007). Anthropological evidence has further shown that African’s family system of polygyny and extended family practice is one of the factors contributing to the continent’s state of poverty and underdevelopment (Lindstrom & Kokko, Citation1998; Sear et al., Citation2002).

Moreover, a family system of polygyny not only has a link with poverty and underdevelopment, its relationship with child health and development has been well documented (Amankwaa, Citation1996; Amey, Citation2002; Brahmbhatta et al., Citation2002; Ukwuani et al., Citation2002; Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007; Sear & Mace, Citation2008; Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014). Frantz et al. (Citation2015) viewed polygyny and other forms of family structure as a central aspect of the family context that influences many children’s health and development outcomes. However, there are divergent views in the literature regarding the association between a family system of polygyny and child health and survival.

On the one hand, scholars have established the relationship between polygyny and poor health outcomes largely through the mechanism of competition for household resources arising from the presence of many women and children in the nuptial unit (Amankwaa, Citation1996; Amey, Citation2002; Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007). This is because the presence of many women and children in the conjugal unit often places much pressure on the scarce household resources, thereby leading to poor nutrient intake (Whitworth & Stephenson, Citation2002). In addition, polygynous union has been well linked with such negative consequences as strife, poverty and hunger, all of which have implication for poor child health outcomes and less survival advantage (Gage et al., Citation1997; Ota & Moffatt, Citation2007; Gyimah, Citation2009).

On the other hand, a number of studies have argued that no significant relationship exists between polygyny and child survival, while some others have argued in favour of a protective advantage of polygyny through the pathway of long duration of breastfeeding and long birth interval (Brahmbhatta et al., Citation2002; Sear et al., Citation2002; Ukwuani et al., Citation2002; Sear & Mace, Citation2008). Available evidence from the literature suggests that the advantage of long duration of breastfeeding and long inter-birth interval offered by the family system of polygyny is premised on the fact that there are many women in the conjugal unit with whom a man can have sexual intercourse.

Thus, as argued, the literature does not provide a strong consensus regarding the direction of relationship between polygyny and child health and survival. Also, while it is plausible to posit that a polygynous family system is a reflection of broader socio-economic and cultural contexts, extant studies have largely failed to view it as such. Further, although a family system of polygyny is viewed as a product of culture in a society, its effects on development and health outcomes of children as a reflection of a broader socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts has not been properly placed within the research agenda. It is thus hypothesised in this study that polygyny will work differently through the pathway of broader socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts to influence child survival differentially across varying contexts. Although, the implication of polygyny for childhood mortality is well established in the literature, evidence remains sparse on whether polygyny influences child survival differentially across varying socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts. This study aimed to address this knowledge gap.

2. Some theoretical perspectives on polygyny and child survival

A number of hypotheses have been advanced in respect of the relationship between polygyny and child health/survival. Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli (Citation2014) put forward three hypotheses in regards to the pathway of influence, through which polygyny influences child health and survival. The first concerns the resources dilution hypothesis, whereby the presence of many women and children in polygynous families is seen to reduce per-capita resources at the household level, thus leading to poor childhood nutrition and susceptibility to diseases and death. The second theoretical explanation concerns the poorer utilisation of maternity care in polygynous family settings relative to monogamous families. The former hypothesis (i.e. resource dilution) thus seems to underpin the latter, largely through incapacitation to utilise maternity care as a result of resource constraints. The third theoretical proposition is in respect of the possible influence of polygyny on child health through gender inequality. Scholars have argued that the problem of gender inequality is more pronounced in polygynous unions compared with monogamous marriages (Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007; Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014). The issue of gender inequality in polygynous families could also be linked directly or indirectly with resources dilution, and this may negatively affect the health of the mother and the child, particularly the sex that is less favoured (mostly the girl-child in many African settings).

Thus, to take the discourse further, we put forward another hypothesis in this study regarding the possible influence of polygyny on child health and survival. Considering that men and women of different strata and status practise polygynous marriage, perhaps due to cultural norms and values as noted in the demographic and anthropological literature, we thus hypothesised that polygyny will influence under-five mortality differentially across diverse socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts. We put this argument differently and state simply: does the effect of a polygynous family system on child survival vary significantly across different socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts? Because of the fact that young children are largely dependent on their parents, the socio-economic status of the parents is often used as a proxy to gauge children’s access to resources (Desai, Citation1992). Given the resource dilution hypothesis in respect of polygynous families, and because the literature has established better health outcomes for children in higher income families compared with those in poorer families (Desai, Citation1992; Adedini et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b), it is plausible to expect poorer health outcomes for children in polygynous unions compared with those in monogamous marriages, particularly if resources are held constant across households. However, if resources are made to vary and children are found in high-income households, it is plausible to argue that polygyny will be unlikely to have uniform effects on health outcomes of children across households with different socio-economic status. In other words, we posited that children in higher-income polygynous families are unlikely to have less survival advantage than those in monogamous families. Moreover, we hypothesised that children in better-off neighbourhoods will benefit from the social capital offered by the good socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts, like urban settings and rich neighbourhoods. To test this hypothesis, we analysed data from four countries, selected to represent the four blocs of sub-Saharan Africa.

3. Data and method

This study utilised pooled data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) of four sub-Saharan African countries. These countries were selected for three reasons: availability of relevant information in the recently conducted DHSs; high prevalence of polygynous unions in the selected countries relative to other countries; and the need to represent the four sub-regions of sub-Saharan Africa — East (Kenya), Middle (Niger), Southern (Zimbabwe) and Western African countries (Nigeria).

The children’s recode data of the most recent nationally representative data of the selected countries – Kenya (2014), Niger (2012), Nigeria (2013) and Zimbabwe (2010–11) – were utilised in the study. The DHSs employed similar methodology in data collection across countries, and this permits comparative analysis and comparability of findings across countries. The DHSs employed a multi-stage cluster design in selecting representative samples of women aged 15 to 49 in various countries. Detailed reports on data collection procedures have been published in the DHS reports of the selected countries (ZIMSTAT & ICF International, Citation2012; INS & ICF International, Citation2013; National Population Commission & ICF International, Citation2014; KNBS and ICF International, Citation2015).

To address the objective of this study, analysis was restricted to samples of 8384 children (Kenya), 12 203 children (Niger), 29 778 children (Nigeria) and 4477 children (Zimbabwe) of women who were ever married or were in a union. These samples constituted children that were delivered within five years before the survey. This translates to a total of 54 842 children in the pooled dataset.

3.1. Variable definition and measurement

3.1.1. Outcome variable

This study presents empirical findings on an important public health and developmental issue – under-five mortality, defined as the risk of death before age five. The variable was measured as the duration of survival since birth in months.

3.1.2. Independent variables

The main explanatory variable in this study is family structure, defined as the type of conjugal unit where a child is born or raised. Family structure was categorised as monogamous union or polygynous union. The selected control variables at the individual level included birth interval, maternal age, maternal age at birth, education, religion, parity and household wealth index. The selected variables at the contextual level are place of residence, community-level education and community poverty. Apart from the place of residence, the other selected community-level variables were constructed by aggregating the individual and household-level variables at the level of primary sampling units, which served as a proxy for neighbourhood or community. The constructed variables were later divided into tertiles, and categorised as low concentration, medium concentration and high concentration of individuals with a given attribute.

3.2. Statistical analysis

Three levels of analysis (univariate, bivariate and multivariate) were undertaken in this study. At the first level of analysis, the percentage distribution of sample’s characteristics was determined. At the bivariate level of analysis, we present both descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive results included the percentage distribution of the sample’s characteristics according to family structure. The inferential statistics at the bivariate level included presentation of results from the log-rank test. At the multivariate level, Cox proportional hazard regression analysis and multi-level survival analysis were undertaken to tease out the effects of polygyny and the selected individual-level and contextual characteristics on under-five mortality. The study employed Cox proportional regression analysis, given the time-to-event nature of the outcome variable.

Five Cox regression models were fitted using the pooled data for all of the selected countries. Model 1 is a one-variable model which considered the family structure covariate, control variables and the interaction variables in the analysis independently. Model 2 adjusted for selected individual-level variables. The contextual variables were adjusted for in Model 3, while Model 4 was the full model which incorporated all of the selected variables. In addition, Model 5 was fitted with interaction terms to demonstrate whether the effects of polygyny significantly vary across different socio-economic or neighbourhood contexts.

Further, multilevel Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was done to account for the clustering of observations. Five multi-level models were fitted using the pooled data for all the selected countries. Given that the outcome variable is a time-to-event measure, and because the assumption of homogeneity of residual variance in standard regression modelling is often not valid due to the hierarchical structure of the clustered data, this study employed multi-level modelling to account for the heterogeneity of residual variance.

In the Cox model, the probability of under-five mortality was considered as the hazard (Adedini et al., Citation2015a). The hazard was modelled using Equations (1) to (3):(1)

where X1 … Xk are a group of independent variables and H0(t) is the baseline hazard at time t, representing the hazard for a person with the value zero for all of the covariates. By dividing both sides of Equation (1) by H0(t) and taking logarithms, the equation becomes:(2)

where H(t)/H0(t) is considered the hazard ratio. The coefficients bi … bk are estimated by Cox regression.

In estimating the fixed and random effects in the multi-level survival model, we assumed that the hazards of any two units are proportional as has been postulated previously in an earlier study (Rabe-Hesketh et al., Citation2004). This is modelled as follows:(3)

In the third equation, two levels are indicated. These are denoted by the two subscripts, with i representing the level one units (individuals) and j representing the level two units (neighbourhoods or communities), denotes the linear predictor of the generalised linear latent and mixed model (GLLAMM).

All multi-level analyses were conducted using the GLLAMM implementable in Stata software (version 13.0). Results on measures of association were presented as the hazards ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Measures of variations were expressed as intra-class correlation and proportional change in variance.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

Percentage distributions of the study sample according to selected individual-level characteristics are presented in . Of the 54 842 children in the pooled data for all the selected countries, about half were children of uneducated women (49.7%), women aged 25 to 34 (50.5%), women whose maternal age at birth was 25 to 34 years (44.1%) and women with parity of five or higher (39.8%). Also, Christians comprised 36.9% of the sample and respondents in the poorest households constituted the majority (23.1%). Most of the children had a preceding birth interval of 36 months or higher (40.4%).

Table 1. Distribution of respondents by family type and according to selected individual-level characteristics.

further presents the percentage distributions of the study sample by family structure and according to selected background characteristics. All of the selected characteristics varied significantly between the family types (p < 0.05). As can be seen in , the majority of the Christians were in monogamous union (39.2%) while the highest proportion of the Muslims was in polygynous marriages (53.2%). Interestingly, most of the women in the poorest households were in polygynous unions, with 29.4% being children of the poorest women in polygynous unions compared with 10.4% being children of the richest women in polygynous marriages. Results further showed that higher-order children were more likely to be born in polygynous unions (55.8%) compared with lower-order children. Also, uneducated women were more likely to be in polygynous families compared with women who had tertiary education (71.6% vs 1.1%).

The distribution of the study sample according to the selected contextual variables is presented in . The largest proportions of the study sample were resident in rural areas (70.9%), poor communities (75.1%) and communities with a low concentration of educated people (35.4%). also indicates that most of the women in polygynous unions were residing in rural areas (81.8%), poor communities (84.5%) and communities with a low concentration of educated people (47.9%).

Table 2. Distribution of respondents by family type and according to selected contextual characteristics.

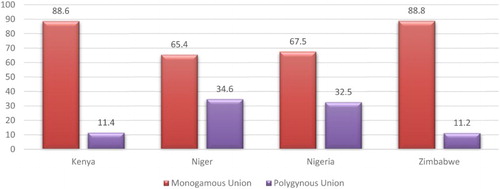

The results across country level () showed that the type of family structure varies significantly across the selected countries (p < 0.001). As shown in , the proportion of the study sample in polygynous union was highest in Niger Republic (34.6%), followed by Nigeria (32.5%), Kenya (11.4%) and Zimbabwe (11.2%).

4.2. Kaplan–Meir estimates and log-rank test

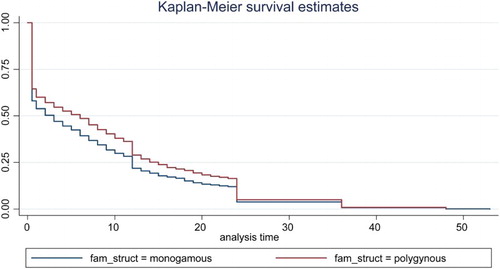

presents the Kaplan–Meier survival estimates showing the duration of survival since birth for children who failed to survive beyond age five. The Kaplan-Meier curve in shows that risks of under-five death were higher for children of mothers in polygynous marriage compared with those in monogamous union. The results of the log-rank test which examined the survival function between the two groups in indicated a significant difference in the distribution of the survival time of the children in monogamous and polygynous unions (p < 0.001).

4.3. Results from multivariate survival analysis

Results of the multivariate analysis from the Cox proportional regression analysis are presented in . Model 1 presents the univariate HRs. The results indicated elevated hazards of under-five death for children in polygynous unions (HR: 1.37, CI: 1.27 to 1.48, p < 0.001) compared with those in monogamous marriages. Adjusting for the selected socio-economic and demographic variables in Model 2 resulted in only slightly plummeted risks of under-five death for children in polygynous unions (HR: 1.15, CI: 1.05 to 1.25, p < 0.01), thus indicating that the influence of a polygynous family system on under-five mortality was independent of socio-economic and demographic characteristics. Incorporating only the selected contextual variables into the analysis in Model 3 also established significantly higher risks of under-five mortality for children in polygynous unions (HR: 1.17, CI: 1.08 to 1.25, p < 0.001) than for those in monogamous unions.

Table 3. Results from Cox proportional hazard model showing the effects of polygyny and selected variables on child survival in selected sub-Saharan African countries.

Moreover, simultaneously adjusting for the selected individual-level and contextual characteristics (Model 4) did not change the significant relationship between under-five mortality and a polygynous family system, but resulted in slightly higher hazards of under-five death for children in polygynous marriages (HR: 1.13, CI: 1.03 to 1.25, p < 0.01) relative to those in monogamous unions. Results from the full model (Model 4) also indicated some selected control variables, including respondent’s age at birth, birth interval, parity, wealth index, place of residence, community poverty and community education as significant predictors of under-five mortality in the selected countries.

In order to assess whether the effects of polygyny on child survival significantly vary across different socio-economic or neighbourhood contexts, we fitted cross-level interaction terms in Models 1 and 5. The results of unadjusted interaction terms (Model 1 in ) indicated lower risks of under-five death for children of educated monogamists (HR: 0.73, CI: 0.65 to 0.82, p < 0.001) and higher risks of under-five death for children of uneducated polygynists (HR: 1.29, CI: 1.19 to 1.40, p < 0.001) compared with the children of uneducated monogamists. Also, results in Model 1 indicated elevated hazards of under-five death for children of monogamists residing in rural areas (HR: 1.39, CI: 1.24 to 1.58, p < 0.001), polygynists resident in urban areas (HR: 1.23, CI: 1.00 to 1.50, p < 0.05) and polygynists in rural areas (HR: 1.85, CI: 1.63 to 2.10, p < 0.001), relative to the children of monogamists in urban areas. The unadjusted cross-level interaction model further indicated more than two-fold higher risks of under-five death for children of monogamists in poor communities (HR: 2.24, CI: 1.69 to 2.98, p < 0.001) and three-fold higher risks of under-five death for children of polygynists in poor communities (HR: 2.98, CI: 2.23 to 3.95, p < 0.001), relative to the children of monogamists in rich communities.

Analysis based on the adjusted cross-level interaction (Model 5) supports the results of unadjusted cross-level interaction in Model 1, but with a slight difference in the findings. For instance, being born in monogamous unions by rural women (HR: 1.17, CI: 1.02 to 1.36, p < 0.01) was associated with significantly higher risks of under-five death, whereas children of mothers in polygynous unions in urban areas had significantly lower risks of under-five deaths (HR: 0.73, CI: 0.57 to 0.92, p < 0.01), relative to children of mothers in monogamous families in urban areas. The results of the cross-level interaction further showed that children of monogamous mothers in poor communities (HR: 1.64, CI: 1.10 to 2.44, p < 0.05) had almost two-fold significantly higher risks of under-five death than the children of monogamists in rich communities. The interaction effects of family structure and maternal education indicated more than two-fold higher risks of under-five deaths (HR: 2.24, CI: 1.46 to 3.45, p < 0.001) for children of uneducated mothers in polygynous unions, and about two-fold higher risks of under-five deaths for children of educated women in polygynous unions (HR: 1.95, CI: 1.19 to 3.21, p < 0.01).

4.4. Results from multivariate Cox proportional hazard model

Multilevel Cox proportional regression analysis was fitted in order to account for clustering of observations. The results are presented in . Results from the null model (Model 0) which was fitted to decompose total variance into its individual and community-level components showed a significant variance across community, thereby justifying the use of multi-level modelling. Inclusion of family structure in the multilevel analysis as the only covariate revealed a significantly higher risk of death before age five for children of mothers in polygynous unions (HR: 1.30, CI: 1.22 to 1.39, p < 0.05) compared with those in monogamous families. Adjusting for the influence of contexts in the multi-level analysis showed that, irrespective of the socio-economic or neighbourhood context where a child is born or raised, the implication of polygyny for under-five mortality was almost similar across contexts (), thus invalidating our study hypothesis. This result affirms the findings established in the interaction terms presented in . The negative effects of polygynous families were further re-echoed in Models 1 to 4 of the multilevel analysis (). For instance, the full model (Model 4) which incorporated all of the individual and community-level covariates indicated significantly elevated hazards of under-five mortality for children of mothers in polygynous families (HR: 1.14, CI: 1.05 to 1.23; p < 0.05) compared with those in monogamous unions.

Table 4. Results from multilevel Cox proportional hazard model showing the effects of polygyny and selected variables on child survival in selected sub-Saharan African countries.

Further results from the full model of multilevel analysis () indicated significantly lower risks of under-five death for children of mothers aged 25 to 34 (HR: 0.72, CI: 0.65 to 0.79, p < 0.01), children with a birth interval of two years or higher (HR: 0.64, CI: 0.58 to 0.70, p < 0.05) and children in the richest households (HR: 0.65, CI: 0.55 to 0.78, p < 0.05) compared with those in the reference categories. At the community level, the protective advantage of urban residence and good education context was established, with children of women residing in rural areas having significantly higher under-five mortality risks (HR: 1.42, CI: 1.30 to 1.55, p < 0.05) compared with those in urban areas. Also, residence in a community with a high proportion of educated women was significantly associated with lower under-five mortality risk (HR: 0.89, CI: 0.80 to 1.00, p < 0.05). Although better-off contexts offered some protective advantage for child survival, results suggest that better-off contexts do not substantially reduce the risks of under-five death for children in polygynous families situated in better-off socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This article examined the influence of family system of polygyny on child survival across different neighbourhood and socio-economic contexts in selected sub-Saharan African countries. Hayase & Liaw (Citation1997) opined that family system of polygyny in sub-Saharan Africa is not just a type of marriage but also a value system which has been resistant to values that accompanied the imported western ideology of monogamy. The present study was conceived and designed based on the competing theories regarding the relationship between family structure and child health outcomes (Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007; Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014; Frantz et al., Citation2015), and based on the evidence that polygyny is practised across different socio-economic strata and neighbourhood structure (NPC & ICF Macro, Citation2014; Adedini et al., Citation2015b).

A number of previous studies have established negative effects of polygyny on child health outcomes (Gage et al., Citation1997; Ukwuani et al., Citation2002; Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007), while some others have indicated no significant relationship between the two phenomena, or better still protective effects of polygyny on child health and survival (Brahmbhatta et al., Citation2002; Sear et al., Citation2002). Studies that affirmed the negative effects of polygyny on child health outcomes suggest that an additional dependant (wife or child) in a polygynous family tends to reduce the per-capita household resources, thereby leading to stiff competition for household resources and poor nutrient intakes. Prior studies also established early marriage, strife and poverty as a possible pathway through which polygyny influences child health and survival (Ota & Moffatt, Citation2007; Gyimah, Citation2009).

Findings from the present study add to the literature by establishing that polygyny significantly contributes to high under-five mortality across different contexts – socio-economic and geographic. It was hypothesised in this study that the negative effects of polygyny on child survival would wane or disappear in a rich or better-off context. However, our findings showed that negative effects of polygyny on child survival only slightly plummeted in rich or better-off socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts. Our results suggest that a polygynous family system tends to increase the risk of under-five mortality across different contexts. For instance, findings showed that polygyny appears to compound the negative effects of lack of formal education on child survival, because risks of under-five mortality were significantly higher for children of uneducated polygynists, relative to the children of uneducated monogamists. Similarly, the results that established elevated hazards of under-five death for children of polygynists residing in urban areas confirmed that polygyny tends to diminish the protective advantage of urban dwelling, while it compounds the negative effects of rural residence on child survival. Furthermore, our results showed that residence in poor communities tends to diminish the protective advantage of monogamous unions on child survival, while polygyny appears to aggravate the negative effects of poor neighbourhood dwelling on child survival, because risks of under-five death were about two-fold significantly higher in the latter than the former.

These findings suggest that irrespective of the socio-economic strata or neighbourhood contexts to which one belongs, a monogamous family system generally offers a greater survival advantage for under-five children while less survival advantage is largely associated with a polygynous family system.

Prevalence of polygyny has not only been reported to differ considerably across sub-Saharan African countries, but also seen as a phenomenon that is significantly influenced by different socio-economic and cultural contexts (Hayase & Liaw, Citation1997). Our study thus adds to the literature by establishing that polygyny, as a by-product of a broader socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts, tends to influence under-five mortality through the influence of the factors operating within the broader social contexts.

Our results further suggest that socio-economic and neighbourhood characteristics play an important role in moderating the relationship between polygyny and child mortality. This confirms the selectivity hypothesis of marriage (Hayase & Liaw, Citation1997; Westoff, Citation2003; Gyimah, Citation2009), whereby women in poorer socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts (such as rural residence, poor communities, uneducated, unemployed and poor) tend to be more involved in polygynous marriages than those in the better-off contexts.

Although we postulated that good socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts would significantly diminish the negative effects of polygyny on child survival, our analysis showed that better-off contexts only slightly reduced the negative effects of polygyny on child survival, while a polygynous family system further compounds the negative effects of poor contexts on children’s survival chances.

In conclusion, given the negative effects of polygyny on childhood survival across different socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts, this study therefore stressed the need for marriage reforms and strict enforcement of a monogamous family system, if significant under-five mortality reduction would be achieved during the post-2015 development era across sub-Saharan African countries with a high level of polygynous unions. This study has a number of limitations. First, the contextual variables, other than place of residence, were generated from individual-level variables. This could introduce some bias. Second, primary sampling units served as a proxy for community. This could misclassify respondents into the wrong administrative boundaries and therefore could introduce bias. Despite these limitations, the study has some strengths. It provides empirical evidence on the influence of polygyny on child survival across varying socio-economic and neighbourhood contexts. Also, the results could be generalised across different countries due to similar methodologies employed by the DHS in different countries.

Acknowledgements

The support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence (CoE) in Human Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CoE in Human Development. Also, the financial supports from the Demography and Population Studies Programme, Wits University (which enabled the first author to attend and present this paper at the Family Demography Conference) are gratefully acknowledged. Comments of the conference participants and those of the anonymous reviewers are sincerely acknowledged. Authors would also like to appreciate the ICF International for authorisation to utilise the DHS data of the selected countries for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adedini, SA, Odimegwu, C, Imasiku, EN & Ononokpono, DN, 2015. Ethnic differentials in under-five mortality in Nigeria. Ethnicity & Health, 20(2), 145–62. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.890599

- Adedini, SA, Odimegwu, C, Imasiku, EN, Ononokpono, DN & Ibisomi, L, 2015. Regional variations in infant and child mortality in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Biosocial Science, 47(2), 165–87. doi: 10.1017/S0021932013000734

- Amankwaa, AA, 1996. Prior and proximate causes of infant survival in Ghana, with special attention to polygyny. Journal of Biosocial Science, 28(3), 281–95. doi: 10.1017/S0021932000022355

- Amey, FK, 2002. Polygyny and child survival in West Africa. Biodemography and Social Biology, 49(1–2), 74–89. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2002.9989050

- Brahmbhatta, H, Bishaia, D, Wabwire-Mangenb, F, Kigozic, G, Wawerd, M, Graya, RH & The Rakai Project Group, 2002. Polygyny, maternal HIV status and child survival: Rakai, Uganda. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 585–92. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00189-7

- Desai, S, 1992. Children at risk: The role of family structure in Latin America and West Africa. Population and Development Review, 18(4), 689–717. doi: 10.2307/1973760

- Frantz, J, Sixaba, Z & Smith, M, 2015. A systematic review of the relationship between family structure and health risk behaviours amongst young people: An African perspective. The Open Family Studies Journal, 7(1), 3–11. doi: 10.2174/1874922401507010003

- Gage, AJ, Sommerfelt, AE & Piani, AL, 1997. Household structure and childhood immunization in Niger and Nigeria. Demography, 34(2), 295–309. doi: 10.2307/2061706

- Gyimah, SO, 2009. Polygynous marital structure and child survivorship in sub-Saharan Africa: Some empirical evidence from Ghana. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 334–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.067

- Hayase, Y & Liaw, K-L, 1997. Factors on polygamy in sub-Saharan Africa: Findings based on the Demographic and Health Surveys. The Developing Economies, 35(3), 293–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1049.1997.tb00849.x

- Institut National de la Statistique (INS) et ICF International, 2013. Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples du Niger 2012. INS et ICF International, Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- KNBS and ICF International, 2015. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. KNBS and ICF International, Calverton, Maryland.

- Lindstrom, J & Kokko, H, 1998. Sexual reproduction and population dynamics: The role of polygyny and demographic sex differences. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 265, 483–8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0320

- National Population Commission, & ICF International, 2014. Nigeria 2013 Demographic and Health Survey report. Abuja, Nigeria.

- NPC & ICF Macro, 2014. 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey.

- Omariba, WRD & Boyle, MH, 2007. Family structure and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: Cross-national effects of polygyny. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(2), 528–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00381.x

- Ota, M & Moffatt, P, 2007. The within-household schooling decision: A study of children in rural Andhra Pradesh. Journal of Population Economics, 20(1), 223–39. doi: 10.1007/s00148-005-0033-z

- Rabe-Hesketh, S, Skrondal, A, & Picklesz, A, 2004. GLLAMM Manual. Division of Biostatistics Working Paper Series, University of California, Berkeley.

- Sear, R & Mace, R, 2008. Who keeps children alive? A review of the effects of kin on child survival. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.10.001

- Sear, R, Steele, F, McGregor, IA & Mace, R, 2002. The effects of Kin on child mortality in rural Gambia. Demography, 39(1), 43–63. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0010

- Smith-Greenaway, E & Trinitapoli, J, 2014. Polygynous contexts, family structure, and infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Demography, 51(2), 341–66. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0262-9

- Ukwuani, FA, Cornwel, GT & Suchindran, CM, 2002. Polygyny and child survival in Nigeria: Age-dependent effects. Journal of Population Research, 19(1), 155–71. doi: 10.1007/BF03031975

- Westoff, CF, 2003. Trends in marriage and early childbearing in developing countries. DHS Working paper.

- Whitworth, A & Stephenson, R, 2002. Birth spacing, sibling rivalry and child mortality in India. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 2107–119. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00002-3

- ZIMSTAT & ICF International, 2012. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2010–11. ZIMSTAT and ICF International Inc, Calverton, Maryland.