ABSTRACT

The family setting has implications for child survival. In this study, the dynamics of maternal union dissolution and childhood mortality were investigated in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Birth history data of 235 454 children from the most recent Demographic and Health Survey conducted in 23 SSA countries were analysed using life table techniques and piecewise exponential hazards models. The results revealed that the childhood mortality rates were 35 vs 32 per 1000 live births (one month), 61 vs 54 per 1000 (11 months) and 95 vs 86 per 1000 (48 months) for children of women in marital dissolution compared with those with intact marriages. Despite controlling for background variables, the risk of under-five mortality was significantly higher among children of women in marital dissolution (relative risk = 1.35, confidence interval: 1.30–1.40). The effect of dissolution on childhood mortality has not changed since the 1990s. Marital stability is an important social structure for child survival.

1. Background

The high rate of childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has received increasing attention in policy and research over the past 10 years, in view of the pursuit of globally accepted developmental goals. Previous research has highlighted several individual demographic and economic, familial and community factors that influence child survival (Akinyemi et al., Citation2013; Subramanian & Corsi, Citation2014; Adedini et al., Citation2015). These findings have influenced the design of a wide array of intervention programmes. Prominent among these are maternal newborn and child healthcare initiatives, as well as immunisation against vaccine preventable diseases (Kerber et al., Citation2007; Zuehlke, Citation2009). As important as these individual-level programmes are, the family is also a critical component given that it is the channel through which children are born (Beegle et al., Citation2010). Children are born mostly from formalised or informal heterosexual unions/family units. These unions/families provide the environment for children’s growth and development, as well as uptake of diverse interventions to enhance children’s health and survival. This implies that the success of child survival programmes depends on the status and general well-being of these unions/families. For instance, a union/family stressed by marital problems is not likely to be able to pay adequate attention to the care of children (Bzostek & Beck, Citation2011). Unfortunately, previous research, policies and programmes on child health and survival in SSA have paid little attention to the central roles of unions/families in children’s well-being. A greater proportion of existing studies on families and child health and well-being have concentrated on western countries, especially in North America and Europe (Fomby & Cherlin, Citation2007; Gorman & Braverman, Citation2008; Amato, Citation2010). The general consensus in many of these studies is that union/family/marital dissolution has negative consequences on children’s health and developmental outcomes (Fomby & Cherlin, Citation2007; Amato, Citation2010). For example, children of divorced parents are more likely to be malnourished, suffer psychological stress and have poor academic performance.

There have been studies which have looked at the relationship between child health and mortality, household structure, family type and maternal characteristics such as educational level, socio-economic status and empowerment status in SSA (Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007; Gyimah, Citation2009; Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014; Gupta et al., Citation2015; Akinyemi et al., Citation2016). The relationship between single motherhood (Clark & Hamplova, Citation2013; Ntoimo & Odimegwu, Citation2014) and childhood mortality (Smith-Greenaway & Clark, Citation2015) has also received attention. The common finding is that children of single and divorced mothers have poorer health outcomes than those from intact unions/families. The nature of the relationship, however, varied from one country to another (Clark & Hamplova, Citation2013; Ntoimo & Odimegwu, Citation2014).

Variables such as urbanisation, education and household wealth index are correlated with both divorce and childhood mortality (Clark & Brauner-Otto, Citation2015). Although urbanisation is positively correlated with divorce among women, it also enhances survival of under-five children via better access to modern infrastructure and child health care services (Fayehun, Citation2010; Bocquier et al., Citation2011). Some studies also reported that higher education encourages divorce because educated women are autonomous and usually have their own economic resources that enable them to live independently (Takyi & Broughton, Citation2006; Wilson & Smallwood, Citation2008). Furthermore, the divorce selection hypothesis posits that economically endowed women could positively select into divorce (Fomby & Cherlin, Citation2007). In such instances, divorce would not be expected to constitute a risk for child survival. A few other studies found the opposite; that is, education enhances marital stability because more educated women are likely to remain married (Takyi & Gyimah, Citation2007; Grant & Soler-Hampejsek, Citation2014). Therefore, the inter-relationships between divorce (union dissolution), childhood mortality and their determinants require further empirical study. This is even more pertinent in SSA, where different forms of family transitions are underway (Defo & Dimbuene, Citation2012). This study attempts to expand the existing body of knowledge on maternal union dissolution and childhood mortality in four ways.

First, the study provides a holistic view of the relationship between union dissolution and child survivorship, by adopting a broader definition for marital dissolution as being divorce, separation, or widowhood. To date, only one study from Burkina Faso in West Africa (Thiombiano et al., Citation2013) has adopted this approach to investigate marital dissolution and childhood mortality. The study showed that children of women in marital dissolution had higher mortality risks. Previous studies on marital dissolution and childhood mortality have used divorce as an indicator of the former (Amato, Citation2010; Smith-Greenaway & Clark, Citation2015). However, divorce is just one form of union dissolution especially in SSA. Other forms include separation and widowhood. Each of the three has similar consequences of depleting the economic resources available for children’s health and survival, depending on the socio-economic status of the mother and household.

Second, evidence suggests that the remarriage rate in SSA is reasonably high (Isiugo-Abanihe, Citation1998; de Walque & Kline, Citation2012). In addition, some studies also show that union dissolution or family instability has cumulative negative effects on child health outcomes (Amato, Citation2010; Goldberg, Citation2013). A woman may be currently married, and the marriage may not be her first. Differences in health and survival of children of women in higher order marriages relative to first marriages are not clear. This study provides evidence for the influence of previous history of union dissolution on childhood mortality.

The third perspective in which this study adds to existing knowledge is in terms of sub-regional variations in union dissolution and childhood mortality in SSA. Union dissolution is least prevalent in Western Africa and highest in the Southern region (Clark & Brauner-Otto, Citation2015). Childhood mortality, on the other hand, shows a different pattern with higher rates in the Western and Central regions and lower rates in Eastern and Southern Africa (UNICEF et al., Citation2014). Another study argued that the effect of divorce on child mortality is more severe in areas where divorce is rare, and vice versa (Smith-Greenaway & Clark, Citation2015). Although this information is useful, further research is needed to clearly characterise the relationship between union dissolution (divorce, separation and widowhood) and childhood mortality in the four sub-regions of SSA. Furthermore, this third perspective provides much-needed insight into the socio-economic context of marital dissolution, given that certain maternal characteristics such as secondary or higher maternal education and a rich household wealth index are associated with lower childhood mortality. It is therefore important to investigate the mortality risks among children born to educated women or women who live in rich households and who have experienced union dissolution.

Lastly, this study investigates whether the relationship between union dissolution and childhood mortality has changed over time in the presence or absence of its known determinants. Childhood mortality has declined consistently in several SSA countries in the past decade. This decline has been reportedly driven by improvements in maternal and child health utilisation; namely antenatal care, skilled delivery and childhood vaccination amongst others (Akinyemi et al., Citation2013; Subramanian & Corsi, Citation2014). Meanwhile, a recent study on trends in divorce in SSA (Clark & Brauner-Otto, Citation2015) showed that union dissolution has not changed significantly in the past three decades. Knowledge of changes in the relationship is important because of its implications for child survival interventions. For instance, if the relationship remains stagnant, it means that children of women who have experienced union dissolution would continue to be disadvantaged irrespective of the availability of child health or survival programmes.

From the four perspectives highlighted, this study aims to describe the dynamics of maternal union dissolution and childhood mortality in SSA by providing answers to the following questions:

What is the independent association between current maternal union dissolution (divorce, separation and widowhood) and childhood mortality in SSA?

Does repeated/recurrent maternal union dissolution have any independent association with childhood survivorship?

Does the relationship between maternal union dissolution and under-five mortality vary by sub-regions and socio-economic context of mothers?

Has the relation of maternal union dissolution to childhood mortality changed over time in SSA?

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

Twenty three SSA countries with Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted between 2011 and 2014 were included in the study. The choice of 2010 as the cut-off year was to provide data on a relatively recent period which did not exceed more than five years. The child datasets for these countries were retrieved following approval from MEASURE DHS. Data were merged together into a single pooled dataset with 235 454 children from ever-married women, and subsequently analysed. Data pooling was done to increase statistical power and enhance generalisability to SSA.

To investigate whether the effect of union dissolution has changed over time, additional data were retrieved. Two surveys were selected from eight countries such that:

the first survey was conducted between 1990 and 1999;

the most recent survey was not earlier than 2010;

there is at least an interval of 10 years between the selected repeated DHS dataset in each country; and

in each sub-region of SSA, the two countries that ranked top in the under-five mortality rate (U5MR) in the most recent survey were selected provided the first three criteria were met.

In Western Africa, Nigeria and Niger ought to have been selected; however, both are contiguous and had almost the same U5MR in their most recent surveys – Nigeria had a U5MR of 128 per 1000 and Niger had a U5MR of 127 per 1000. Consequently, the next in rank for U5MR – Cote d’Ivoire – was selected. The analysis included the following selected countries: Cameroun (1991, 2011); Cote d’Ivoire (1994, 2011/2); Gabon (2000, 2012); Mozambique (1997, 2011), Nigeria (1990, 2013), Tanzania (1996, 2010); Uganda (1995, 2011); and Zimbabwe (1994, 2010/1).

2.2. Variables

The dependent variable was childhood mortality, which was treated as an event history outcome. Childhood mortality was defined as the probability of death between birth and the 59th month of life. Children who were alive at the time of survey were censored at their current age (months), while the survival time for dead children was their age at death in months.

The main independent variable was maternal union dissolution categorised as either Yes (1) or No (0). This variable was derived from the current marital status of the mothers of children under five during the survey. Women whose current marital status was divorced, widowed, or separated were categorised as ‘current union dissolution’. Children of never-married women were excluded from the analyses. Two additional proxy measures were derived for union dissolution. The first was an indicator variable for previous history of union dissolution (Yes [1], No [0]). Women who are currently in second or higher order marriages or unions were classified as having previously experienced dissolution. Second, the number of dissolution episodes was captured in another variable categorised as those who have never experienced a union dissolution or ‘none’ (0), women who have been married only once and are currently in dissolution or ‘first order’ (1) and those who have had more than one union and are currently in dissolution or ‘higher order’ (2).

Other explanatory variables included background characteristics of the household, mother and child. The variables were selected based on their established relationship with either union dissolution or childhood mortality (Fuchs et al., Citation2010; Bocquier et al., Citation2011). These variables included household factors (wealth index and place of residence); maternal factors (level of education, occupation, age at first marriage and age at child’s birth); and child factors (birth order and birth interval). At the country level, controls were included for sub-region (West, Central, East and South).

2.3. Analytical methods

Descriptive statistics for all explanatory variables were generated and cross-tabulated by current dissolution status and dissolution episodes. Synthetic life table estimates of childhood mortality were derived using the Kaplan–Meier method. Childhood mortality rates were obtained at 1, 11, 24, 36, 48 and 59 months. The rates were disaggregated by dissolution measures and compared using the log-rank test. The piecewise exponential hazards model was employed to assess the relationship between union dissolution and childhood mortality. This model is a parametric model suitable for event history outcomes when the baseline risk varies across time intervals (Rabe-Hesketh et al., Citation2004). Childhood mortality risk is known to vary between the neonatal and post-neonatal period (Ukwuani et al., Citation2002). To account for the changing risk, the survival time of each child was divided into shorter intervals (within which the baseline risk is assumed constant). In this study, the time intervals used were <1 month, 1 to 11 months, 12 to 23 months and 24 to 59 months.

During model fitting, adjustment was made for the hierarchical structure of the pooled data such that the 235 454 children (level 1) in the sample were nested within 23 countries (level 2). Furthermore, data were weighted to account for the complex sample design used for the DHS. These adjustments were meant to improve the precision of the results. Models were fitted as follows:

Model 1: Dissolution indicators.

Model 2: Model 1 + maternal variables (education, occupation, age at first marriage and age at child’s birth).

Model 3: Model 2 + household variables (wealth quintile and residence).

Model 4: Model 3 + child variables (birth order and birth interval).

Model 5: Model 4 + country-level variables (sub-region).

In the model results, the coefficients and their confidence intervals were exponentiated and interpreted as relative risks.

To investigate the variation across SSA sub-regions, stratified analyses were conducted. To further explore the socio-economic context of marital dissolution, the interaction effects of maternal education, occupation and household wealth index on the relationship between marital dissolution and childhood mortality were analysed.

2.4. Assessment of changes in the relationship between union dissolution and childhood mortality

Separate analyses were conducted for each of the eight countries selected for this component of the study. Changes in this relationship were assessed using confidence intervals. Models were fitted separately to each of the two rounds of DHS data from the same countries. Relationships were presented as relative risks with 95% confidence intervals. If there is an overlap in the confidence interval at the two time points, this suggests that there is no difference in the relationship over time.

For the purpose of simplicity and clarity, only the results for principal independent variables were reported for all models. Furthermore, all the other control variables conform to patterns already established in the literature. Data were analysed using Stata SE version 12.

3. Results

3.1. Childhood mortality and probability of marital dissolution in selected countries

Estimates of childhood mortality and first union dissolution are presented in . In Western Africa, probability of first union dissolution ranged from 9.6% in Mali to 40.4% in Ghana; while childhood mortality rates varied from 54 per 1000 live births in Senegal to 128 per 1000 in Nigeria. In the Central region, union dissolution was more prevalent in Congo-Brazzaville (51.0%) and Gabon (42.9%), but Cameroun (122 per 1000 live births) and Congo DRC (104 per 1000 live births) had the highest childhood mortality rates. Union dissolution probability in the Eastern and Southern regions ranged from 24.2% in Kenya to 39.1% in Zambia. The lowest childhood mortality was found in Namibia (54 per 1000 live births) and Kenya (52 per 1000 live births).

Table 1. Survey year, probability of first union dissolution and under-five mortality rates in the most recent DHS from 23 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

3.2. Descriptive characteristics

shows that the majority of the children’s mothers were aged 20 to 35 years (71.1%). About half of the children’s mothers had no formal education (45.5%), while only 23.3% had secondary or higher educational level. About one third lived in rich households (31.3%), and nearly half (48.8%) were domiciled in households in the poor wealth quintile. In terms of residence, 69.3% lived in rural areas.

Table 2. Background characteristics according to current dissolution status and number of dissolution episodes, most recent DHS for 23 sub-Saharan Africa countries.

Overall, 6.6% of 235 454 under-five children had mothers who were not in a marital or family union (current union dissolution). In terms of dissolution episodes, 12.9% and 1.3% were exposed to first-order and higher order dissolutions respectively. Furthermore, further shows the characteristics of children according to current marital dissolution and dissolution episodes. Just under one third (32.2%) of children who were currently exposed to marital dissolution had mothers with a secondary or higher education.

The sub-regional distribution of exposure to current dissolution was 3.5% in the Western region, 9.6% in the Central, 9.1% in the East and 13.1% in the Southern region of SSA. First-order dissolution was highest in Central Africa (15.7%), followed by the Southern region (13.5%).

3.3. Maternal union dissolution and childhood mortality

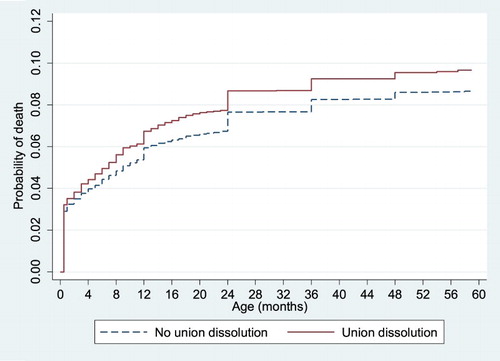

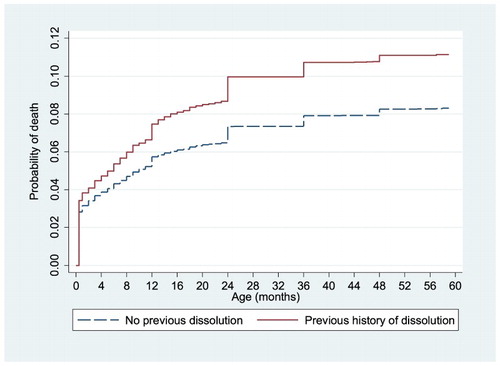

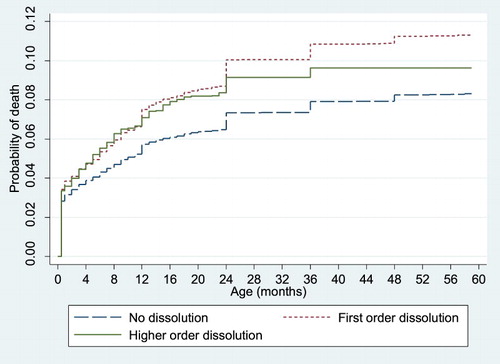

shows that the childhood mortality gap by current maternal union dissolution widened consistently after one month until 48 months of life. shows that the gap, according to previous history of union dissolution, was wider compared with the pattern in . Consistently, children of women with a previous history of union dissolution had significantly higher mortality rates. Furthermore, mortality was higher among children of women who were in first-order dissolutions, compared with those with no marital dissolution and those in higher order dissolutions ().

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier plot of probability of childhood death according to current maternal union dissolution status in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier plot of probability of childhood death according to previous maternal union dissolution history in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier plot of probability of childhood death according to number of maternal union dissolution episodes in sub-Saharan Africa.

Model 1 () reveals that both current and previous marital dissolution increased the risk of childhood mortality. Without controlling for other variables, the risk of childhood death was 24% higher among children of mothers with dissolved unions (relative risk [RR] = 1.24, confidence interval [CI]: 1.17–1.32). Similarly, the risk was 32% higher for children whose mothers had a prior incidence of union dissolution (RR = 1.32, CI: 1.27–1.37). Surprisingly, the sequential addition of explanatory variables in Models 2–5 did not alter the magnitude of the risk in any substantial manner. The results from Model 5 showed that when diverse childhood mortality determinants are controlled, there were no substantial differences in childhood mortality risks across the four sub-regions.

Table 3. Relative risk (95% confidence interval) for the effect of marital dissolution status on childhood mortality in 23 sub-Saharan Africa countries.

shows that first-order union dissolutions (RR = 1.33, CI: 1.27–1.39) exerted slightly greater mortality risk than higher order dissolutions (RR = 1.25, CI: 1.09–1.41). Similar to the pattern of results shown in , the relationship was not affected by the addition of other control variables to the model (Models 2–5).

Table 4. Relative risk (95% confidence interval) for the effect of number of marital dissolution episodes on childhood mortality in 23 sub-Saharan Africa countries.

3.4. Sub-group analysis according to sub-region

To simplify the next set of analyses, we created a single variable called history of dissolution (Yes [1], No [0]) that represents the experience of marital dissolution irrespective of whether dissolution was current or previous, and irrespective of the number of episodes. This variable was used as the main explanatory variable for subsequent analyses. The results are presented in . The relative risk (confidence interval) for the effect of any history of maternal union dissolution on childhood mortality was: West region (RR = 1.35, CI: 1.27–1.43), Central region (RR = 1.23, CI: 1.11–1.36), Eastern region (RR = 1.39, CI: 1.22–1.57) and Southern region (RR = 1.48, CI: 1.32–1.66).

Table 5. Relative risk (95% confidence interval) for the effect of marital dissolution on childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa regions.

3.5. Analysis of interaction effects of maternal education, occupation, household wealth index and marital dissolution on childhood mortality

shows that the contrast (difference) in the risk of childhood mortality between children of women with and without experience of marital dissolution varied by education, occupation and household wealth index in all sub-regions of SSA. The contrast decreased with educational attainment and household wealth index. In the Western region, the risk of childhood mortality was 25% higher among children of women with no formal education who had history of marital dissolution than those who did not. The contrast across educational level in the Central region ranged from 19% (no formal education) to 11% (secondary/higher education). Results for the Eastern and Southern regions showed that the contrast at secondary/higher education was 20% and 22% respectively.

Table 6. Analysis of interaction effects: Marital dissolution history with education, occupation and household wealth index.

3.6. Temporal changes in the relationship between maternal union dissolution and childhood mortality

Although there were inter-country variations, there was no significant change in the relationship over time in all countries (). Generally, there was no difference between the results in Model 1 (only union dissolution) and Model 5 (controls for all selected variables). Furthermore, the strength of the relationship reduced in magnitude (not statistically significant) over time in three countries (Cameroun, Gabon and Zimbabwe). However, the magnitude of the relationship increased in Cote D’ Ivoire, Mozambique, Nigeria and Tanzania – albeit not statistically significant.

Table 7. Analyses of changes in the effect of marital dissolution on childhood mortality between 1990s and 2010s in 10 selected sub-Saharan Africa countries.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The results show that there were significant childhood mortality differentials according to current and previous marital dissolution experience of mothers. This agrees with previous studies in SSA (Clark & Hamplova, Citation2013; Ntoimo & Odimegwu, Citation2014) and other developing countries (Bhuiya & Chowdhury, Citation1997). The probable mechanisms underlying this have been suggested to be stress, disruption of social support from her partner and reduction of socio-economic resources available to mothers and children (DeRose et al., Citation2014). Previous dissolution shows the long-term consequences of marital dissolution. When a union is dissolved, some women remarry. As a result, children born in previous unions may become neglected. Most often, the mother shifts attention to the new union, possibly getting pregnant and giving birth to another child to secure the new relationship. Remarriage thereby constitutes a source of instability for the older child, who may suffer an array of negative consequences (Bzostek & Beck, Citation2011).

Another striking result is the significant differentials according to number of dissolution episodes. Specifically, it was found that childhood mortality rates were higher among children of women in first-order dissolutions than those in higher order dissolutions. A possible explanation for this is that the dissolution of first marriages/unions has greater negative effects on child survival than higher order dissolution episodes. It may imply that women who experienced serial dissolution have learnt to cope with the experience and challenges and are thus able to protect their children against the shock. The descriptive results actually suggest that a higher percentage of children from women with no formal education were exposed to first-order dissolution than higher order marital dissolution. Alternatively, women in first dissolution are likely to be younger and evidence has shown that younger age at marriage is a predictor of marital separation and divorce (Takyi & Broughton, Citation2006; Grant & Soler-Hampejsek, Citation2014). Younger age at marriage will most likely correlate with younger age at birth, which is a risk factor for under-five mortality.

The age pattern of childhood mortality according to marital dissolution status, as revealed in the Kaplan–Meier curves, revealed some interesting dynamics. First, the mortality gap between children within intact marriages and those in dissolution widened from 12 months of age. This pattern is consistent with previous knowledge about the age pattern of under-five mortality (Zhang et al., Citation2013). It also suggests that the effect of marital dissolution on child mortality is age dependent. Ukwuani et al. (Citation2002) reported that polygyny enhances childhood survival (age one to five years), and results in the present study indirectly support the assertion – because from 12 months, children of women in dissolution suffer greater mortality. This may be as a result of a loss of social support networks, which an intact family provides.

Furthermore, the age pattern also shows that in the first 24 months of life mortality rates are similar between children exposed to first-order and higher order dissolutions; but the difference widens afterwards, with those exposed to first order faring worst. This could imply that children aged two and higher of women in first dissolution face adverse conditions that compromise survival, compared with those in higher order dissolutions. A clearer understanding of the mechanism driving this will require longitudinal data substantiated with anthropological evidence.

Results from the multivariable analysis show that the negative effect of union dissolution remained significant, despite adjustment for other variables. These findings, which are similar to those from previous studies in SSA (Thiombiano et al., Citation2013), have implications for child survival programmes and policies. This means that existing programmes have had little or no impact on the relationship between dissolution and child mortality. Therefore, special welfare programmes targeted at children exposed to union dissolution may be needed.

Similarly, the results show that the effect of union dissolution on childhood mortality in SSA has remained the same over the years. Stability in the effect of union dissolution may be a direct consequence of the fact that the probability of marital dissolution itself has remained virtually unchanged in many SSA countries (Clark & Brauner-Otto, Citation2015). This finding is similar to the results provided by Omariba & Boyle (Citation2007), which revealed that the effect of polygyny on child survival remained stagnant over time.

The subgroup analysis suggests that although the magnitude of effect of union dissolution varied, it was still significant across all sub-regions in SSA. This shows that no sub-region is immune to the negative consequences of union dissolution on child health outcomes, notwithstanding the progress made in reducing mortality. It is important to note that although the probability of union dissolution was higher in Eastern and Southern Africa, these are regions with the lowest childhood mortality rates; while Western and Central Africa have lower probabilities of union dissolution but higher mortality rates. Despite this seemingly inverse relationship, the relative risk for marital dissolution history was higher in Eastern and Southern Africa. It thus appears that the prevailing level of marital dissolution has an overbearing influence on child survival.

Some limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the fertility history data used to investigate union dissolution and childhood mortality. Longitudinal data with information on marital history would allow a better understanding of the temporal relationships that may exist between family formation/dissolution/repartnering and child health outcomes. Secondly, the non-availability of data on marital history did not allow an investigation of the role of ex-partner characteristics among women who have experienced marital dissolution. Despite these limitations, the findings are in tandem with results from demographic surveillance system data in Bangladesh (Alam et al., Citation2001), which showed that children born before or after a dissolution had worse probabilities of survival.

This study concludes that children of women who have experienced union dissolution face greater risks of mortality. The mortality risk faced by these children is even higher in first dissolution than higher order dissolutions. The negative effect of marital dissolution on childhood mortality is almost universal across SSA, although slightly higher in the Eastern and Southern regions. This negative effect has remained unchanged since the 1990s. An obvious policy implication of these findings is the need for welfare support programmes for mothers of under-five children who have been divorced, separated or widowed. Such programmes must be designed to provide the necessary cushion against the negative consequences of marital dissolution. This is essential so that their disadvantaged situation does not undermine other efforts aimed at promoting child health and well-being. In terms of research, the effect of family context on children’s growth and development, especially beyond the first five years of life, needs to be further investigated. Further empirical evidence on the timing and long-term cumulative effect of union dissolution is necessary in view of ongoing transitions in family systems and livelihood in SSA.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the DHS programme and implementing agencies in different countries. The support of the Department of Science and Technology-National Research Foundation (DST-NRF) Centre of Excellence in Human Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre of Excellence in Human Development. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adedini, SA, Odimegwu, C, Imasiku, EN, Ononokpono, DN & Ibisomi, L, 2015. Regional variations in infant and child mortality in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Biosocial Science 47, 165–87. doi: 10.1017/S0021932013000734

- Akinyemi, JO, Bamgboye, EA & Ayeni, O, 2013. New trends in under-five mortality determinants and their effects on child survival in Nigeria: A review of childhood mortality data from 1990–2008. African Population Studies 27, 25–42. doi: 10.11564/27-1-5

- Akinyemi, JO, Chisumpa, VH & Odimegwu, CO, 2016. Household structure, maternal characteristics and childhood mortality in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Rural Remote Health 16, 3737.

- Alam, N, Saha, SK, Razzaque, A & van Ginneken, JK, 2001. The effect of divorce on infant mortality in a remote area of Bangladesh. Journal of Biosocial Science 33, 271–8. doi: 10.1017/S0021932001002711

- Amato, PR, 2010. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and New developments. Journal of Marriage and Family 72, 650–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

- Beegle, K, Filmer, D, Stokes, A & Tiererova, L, 2010. Orphanhood and the living arrangements of children in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 38, 1727–46. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.06.015

- Bhuiya, A & Chowdhury, M, 1997. The effect of divorce on child survival in a rural area of Bangladesh. Population Studies 51, 57–61. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000149726

- Bocquier, P, Madise, NJ & Zulu, EM, 2011. Is there an urban advantage in child survival in sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from 18 countries in the 1990s. Demography 48, 531–58. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0019-2

- Bzostek, SH & Beck, AN, 2011. Familial instability and young children’s physical health. Social Science & Medicine 73, 282–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.014

- Clark, S & Brauner-Otto, S, 2015. Divorce in sub-Saharan Africa: Are unions becoming less stable? Population and Development Review 41, 583–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00086.x

- Clark, S & Hamplova, D, 2013. Single motherhood and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: A life course perspective. Demography 50, 1521–49. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0220-6

- de Walque, D & Kline, R, 2012. The association between remarriage and HIV infection in 13 sub-Saharan African countries. Studies in Family Planning 43, 1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00297.x

- Defo, BK & Dimbuene, ZT, 2012. Influences of family structure dynamics on sexual debut in Africa: Implications for research, practice and policies in reproductive health and social development. African Journal of Reproductive Health 16, 147–72.

- DeRose, L, Corcuera, P, Gas, M, Fernandez, LCM, Salazar, A & Tarud, C, 2014. Family instability and early childhood health in the developing world. In Mapping family change and child well-being outcomes. Child TRENDS, New York.

- Fayehun, O, 2010. Household environmental health hazards and child survival in Sub-Saharan Africa. DHS Working Papers No. 74. ICF Macro, Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Fomby, P & Cherlin, AJ, 2007. Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review 72, 181–204. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200203

- Fuchs, R, Pamuk, E & Lutz, W, 2010. Education or wealth: Which matters more for reducing child mortality in developing countries? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 8, 175–99. doi: 10.1553/populationyearbook2010s175

- Goldberg, RE, 2013. Family instability and early initiation of sexual activity in western Kenya. Demography 50, 725–50. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0150-8

- Gorman, BK & Braverman, J, 2008. Family structure differences in health care utilization among U.S. children. Social Science & Medicine 67, 1766–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.034

- Grant, MJ & Soler-Hampejsek, E, 2014. HIV risk perceptions, the transition to marriage, and divorce in southern Malawi. Studies in Family Planning 45, 315–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00394.x

- Gupta, AK, Bortkotoky, K & Kumar, A, 2015. Household headship and infant mortality in India: Evaluating the determinants and differentials. International Journal of MCH and AIDS 3, 44–52.

- Gyimah, SO, 2009. Polygynous marital structure and child survivorship in sub-Saharan Africa: Some empirical evidence from Ghana. Social Science & Medicine 68, 334–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.067

- Isiugo-Abanihe, UC, 1998. Stability of marital unions and fertility in Nigeria. Journal of Biosocial Science 30, 33–41. doi: 10.1017/S0021932098000339

- Kerber, KJ, de Graft-Johnson, J, Bhutta, ZA, Okong, P, Starrs, A & Lawn, J, 2007. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: From slogan to service delivery. The Lancet 370, 1358–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5

- Ntoimo, LFC & Odimegwu, CO, 2014. Health effects of single motherhood on children in sub-Saharan Africa: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 14, 1145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1145

- Omariba, DWR & Boyle, MH, 2007. Family structure and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: Cross-national effects of polygyny. Journal of Marriage and Family 69, 528–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00381.x

- Rabe-Hesketh, S, Skrondal, A & Pickles, A, 2004. GLLAMM Manual. U.C. Berkeley Division of Biostatistics Working Paper Series.

- Smith-Greenaway, E & Clark, S, 2015. Parental divorce and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: Does context matter? PSC Research Reports 15-843. Institute of Social Research, University of Michigan.

- Smith-Greenaway, E & Trinitapoli, J, 2014. Polygynous contexts, family structure, and infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Demography 51, 341–66. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0262-9

- Subramanian, SV & Corsi, DJ, 2014. Association among economic growth, coverage of maternal and child health interventions and under-five mortality: A repeated cross-sectional analysis of 36 sub-Saharan African countries. DHS Analytical Studies No. 38. ICF Interneational, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- Takyi, BK & Broughton, CL, 2006. Marital stability in sub-Saharan Africa: Do women autonomy and socio-economic situation matter? Journal of Family and Economic Issues 27, 113–32. doi: 10.1007/s10834-005-9006-3

- Takyi, BK & Gyimah, SO, 2007. Matrilineal family ties and marital dissolution in Ghana. Journal of Family Issues 28, 682–705. doi: 10.1177/0192513X070280050401

- Thiombiano, BG, LeGrand, TK & Kobiané, J-F, 2013. Effects of parental union dissolution on child mortality and child schooling in Burkina Faso. Demographic Research 29, 797–816. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.29

- Ukwuani, FA, Cornwell, GT & Suchindran, CM, 2002. Polygyny and child survival in Nigeria: Age-dependent effects. Journal of Population Research 19, 155–71. doi: 10.1007/BF03031975

- UNICEF, WHO, World Bank and United Nations. 2014. Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2014. Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York, 10017 USA: United Nations Children’s Fund.

- Wilson, B & Smallwood, S, 2008. The proportion of marriages ending in divorce. Population Trends 131, 28–36.

- Zhang, L, Maher, D, Munyagwa, M, Kasamba, I, Levin, J, Biraro, S & Grosskurth, H, 2013. Trends in child mortality: A prospective, population-based cohort study in a rural population in south-west Uganda. Paediatrics and International Child Health 33, 23–31. doi: 10.1179/2046905512Y.0000000041

- Zuehlke, E, 2009. Child mortality decreases globally and immunization coverage increases, despite unequal access. Population Reference Bureau, Washington, DC.