ABSTRACT

This paper explores the range of functions undertaken by the University of Fort Hare (UFH) over its 100-year history and in what ways it has carried these out. Drawing on the framework developed by Castells on the functions performed by universities, the paper shows that UFH’s role in three of these functions – namely, in the production of values for individuals and social legitimation for the state, in the formation of the dominant elite, and in the training of the labour force – has shifted and changed along with the different imperatives and conditions of the colonial, apartheid and post-1994 democratic eras in South Africa. By contrast, UFH’s role in the production of scientific knowledge is a relatively recent development, but one which has strengthened rapidly.

1. Introduction

Building on the ideas of scholars such as Alexander von Humboldt, Cardinal Newman and Clark Kerr, Manuel Castells theorised the core functions of the university within the changing conditions of globalisation and the knowledge economy. According to Castells (Citation2001:206–12), historically, and to a greater or lesser extent, universities play a role in four functions, which may be summarised as follows:

As ideological apparatuses involved in the production of values (citizenship) for individuals, and in the social legitimation for, or contestation of, the state. Despite claims to the contrary, the formation and diffusion of ideology is still a fundamental role of modern universities.

The selection of the dominant elites, which is accompanied by a socialisation process that includes the formation of networks for the social cohesion of the elite, as well as a social configuration which makes a distinction between the elite and the rest of society. Despite increased access to and participation in higher education over the past few decades, and greater differentiation between universities (where some have become more elite and other less so), the university remains a meritocratic selector of elites.

Training of the labour force, which has always been a basic function of the professional university – from the training of church bureaucrats to the Chinese Imperial bureaucratic systems, which extended to the emerging professions of medicine, law and engineering. Over time, the conception of training changed from the reproduction or transmission of ‘accepted’ knowledge to ‘learning to learn’, ‘continuous education’ or creating ‘self-programmable’ workers, all of which refer to the ability to adapt to different occupations and new technologies throughout one’s professional life.

The production of scientific knowledge follows the emergence of the German research university during the second half of the eighteenth century, and later the American Land Grant University model, with its specific focus on science with application into society. This knowledge production function is now an imperative in the development of knowledge economies.

Importantly, Castells argued that no single university can fulfil all of these functions simultaneously or equally well, essentially compelling universities to find ways of managing the tensions that arise from performing often contradictory functions. And, since institutions often shift or change functions, the extent to which the university is able to manage these tensions depends on institutional capacity (academic and managerial) as well as the existence of a national higher education and research system (ibid.: 14).

In this paper, we draw on Castells’ framework in order to reflect on the range of functions undertaken by the University of Fort Hare (UFH) over its 100-year existence. In addition to an historical and sociological account, we also consider key performance indicators as a proxy for an assessment of the extent to which UFH has succeeded in fulfilling its training and knowledge production functions. Unless otherwise indicated, the figures presented in this paper are drawn from Cloete et al. (Citation2016).

2. The University of Fort Hare in the post-1994 context

The much-anticipated transformation of higher education following the transition to democracy in 1994 confronted South African universities, and Fort Hare among them, with very complex and contradictory challenges. As Badat (Citation2004:23) observed, policy-making and transformation were not only conditioned by visions, goals and polices, but also the paradoxes, ambiguities, contradictions, possibilities and constraints of the structural and conjectural conditions at the time.

Specifically, UFH was faced with two major challenges. First, and rather ironically, joining the national university system resulted in a reduction in government funding. Under the apartheid regime, it had received more funds from the Ciskei homeland government (on average, about 55% more) than was paid to a comparably-sized South African university. Secondly, under tremendous pressure to transform their racial profiles, historically advantaged (white) universities attracted and recruited the best black students and staff, resulting in a brain drain from UFH and a number of other historically black institutions.

As a result, by 2000, when the Minister of Education appointed a National Working Group (NWG) to assist with the reorganisation of the apartheid higher education institutional landscape, through processes of merger and incorporation, the overall picture of Fort Hare was that while it had a proud history in South African higher education, it was essentially a rural university in a small and remote town. According to the NWG report (MoE, Citation2002), declines in its intake of first-time entering undergraduates (down by 16% since 1995) had affected its enrolment stability, forcing the university to rely on the registration of large numbers of teachers for in-service programmes in education. Its graduation rates also declined (by 32%) and its research outputs were significantly low. Weak financial indicators towards the end of the 1990s reflected poor liquidity, and unsustainable levels of personnel expenditure relative to income received. If various environmental conditions became adverse, then Fort Hare’s ability to survive would be placed in doubt.

The plan proposed by the NWG was bold in terms of changing the institutional landscape, and radical in the South African context since, instead of the usual focus on human resources, it exhibited strong undertones of regional and metropolitan development, something unheard of in South Africa before. Specifically, with regard to the Eastern Cape, the NWG proposed that one multi-campus university should be established in the East London metropolitan area and in the rural areas to the north and north-west of the city. This would involve the merger of Rhodes University with UFH; a reduction in academic programmes offered on the Alice campus of UFH; and the disestablishment of the University of Transkei (apart from the incorporation of its medical faculty into the new university). This new higher education institution would be expected to offer only university programmes, and to develop a major East London campus as the base from which it would grow and link to the designation of East London as an industrial development zone by the provincial government (ibid.).

This proposed merger and incorporation was rejected by the South African government in favour of preserving and strengthening the heritage of UFH, given its role and history in the development of black intellectuals and social and political leaders, both in South Africa and Africa more generally (ibid.: 14). In the end, UFH was merged with the East London campus of Rhodes University in 2004 and retained its status as a ‘traditional’ university (a category alongside the newly-created comprehensive universities and universities of technology). As a traditional university, the government expectations were that UFH would offer basic academic programmes up to the three-year degree level in the sciences and humanities, as well as four- and five-year degrees which could lead to accreditation in a recognised profession, rather than undergraduate vocational diplomas or certificates.

3. Reflections on the functions undertaken by the University of Fort Hare

Over the course of its 100-year history, UFH has made its own unique contributions, to larger or lesser degrees, to the four functions of universities outlined by Castells. As will be seen, the university’s role in the first three functions – namely as ideological apparatus, and in the formation of the dominant elite and training of the labour force – has shifted and changed along with the different imperatives and conditions of the colonial, apartheid and post-1994 democratic eras. By contrast, UFH’s role in the production of knowledge is a relatively recent development, but one which has strengthened rapidly.

3.1. Ideological and elite selection functions

For much of its existence, UFH has largely been defined as a point of contestation to the dominant colonial values of the white-dominated society. Originally established in 1916 as the South African Native College, it was created specifically for selecting and educating African elites, including the children of chiefs. Elite in this sense refers to the percentage of the population that participates in higher education. Even by 1986, only 5% of Africans in the 20- to 24-year-old age group were in higher education, compared to more than 60% of whites. But the African students did not come from elite backgrounds or schools (NCHE, Citation1996).

With so few university opportunities for Africans during apartheid, Fort Hare attracted the crème de la crème – not only from South Africa, but also from other African countries. However, in the post-apartheid era, top students and staff have been attracted to and recruited by the world-ranked institutions in urban areas like Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria and Durban.

At an ideological level, the Christianising and ‘civilising’ functions of the university were seen as paramount, and were reflected in a curriculum which focussed on subjects like theology, education and social work. In the British-inspired colonial model of indirect rule, it was necessary for Africans to be educated to perform administrative tasks to support the functioning of the system. This included training clerks, teachers, nurses and bureaucrats, who could be sent out to service communities in the African reserves, and to ensure that they were well-administered, did not revolt, and that taxes were collected. In short, the university was seen to fulfil a crucial ideological and social function in legitimising state power and authority (Kerr, Citation1968; Massey, Citation2010).

As far as the missionaries, white academics and administrators of the university were concerned, the institution had potential beyond this limited role. They worked with dedication – not only to produce black state functionaries, but also to train Africans in disciplines such as science, Latin, literature and philosophy. High-level postgraduate academic training in these areas was, however, not offered at Fort Hare. Nevertheless, some of the students that attended Fort Hare in the first half of the twentieth century were able to travel overseas, sometimes with support from the university, to become medical doctors, scientists and academics in their own right. Two outstanding examples of this were DTT Jabavu and ZK Matthews, both of whom started at Fort Hare and then trained overseas in the United Kingdom and America, before returning to take up academic posts at the university. In fact, ZK Matthews was later to become the first black acting vice-chancellor of the university in the 1950s (Kerr, Citation1968; Higgs, Citation1997).

The presence of black academic staff at the institution from the late 1920s, together with an admissions policy which allowed people of all races to enrol, created a space for critical debate and engagement with issues of racism and white domination. Under the auspices of its mixed student body, in the 1930s UFH articulated an ideology of non-racialism that it put into practice on campus. The university was also a site where the Hertzog Bills of 1936, which entrenched land alienation and removed the limited political rights Africans enjoyed on the voter’s role in the Cape Province, were fiercely debated and contested. In this period, the student body at the university, with support from academic staff, emerged as a major site of resistance to both segregation and apartheid (Kerr, Citation1968; Higgs, Citation1997).

In the 1940s, this role was further entrenched through the participation of staff and students in drafting documents such as the ‘Africans’ Claims in South Africa’ manifesto for equal rights adopted by the African National Congress (ANC) in 1943, and later in the formation of the ANC Youth League. This proved to be decisive in the development of mass-based resistance politics in South Africa. Both the ANC and its Africanist off-shoot, the Pan Africanist Congress, were reinvented in the 1950s on the basis of the political energy and resistance at UFH. The ANC Youth League at Fort Hare was arguably the political engine for this transformation of resistance politics and the formation of new and more radical forms of African nationalism.

In 1959, the apartheid government acted decisively against Fort Hare and other institutions that promoted a subversive resistance politics, by passing the Extension of University Education Act which made provision for the establishment of separate tertiary institutions for blacks, Indians, coloureds and whites. As such, this Act aligned African higher education with ‘bantu education’, stripping mission institutions of any role in the university, and transformed universities like Fort Hare into Bantustan universities. The new function of UFH was thus to assist the apartheid state in transforming the tiny and isolated Ciskei Native Reserve (within which Fort Hare was located) into a Xhosa national state. In this period, UFH lost its progressive staff, who either resigned or were weeded out by the new Afrikaner, quasi-military leadership of the university. The students, however, refused to accept the new dispensation and continued to use the campus to resist apartheid. In the teeth of apartheid repression, students of Fort Hare continued to fly the flag of African liberation. But, in practice, many of its graduates were press-ganged into the homeland bureaucracy, which was later amalgamated into the post-apartheid Eastern Cape provincial administration (Massey, Citation2010; Bank & Bank, Citation2013).

In the post-apartheid period, the intellectual and political role of Fort Hare in the creation of African nationalism in southern Africa has been lionised and acknowledged globally. As an institution, it stands alone in producing five post-independence African heads of state, as well as accounting for the majority of the liberation icons in South Africa, including Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe and Govan Mbeki. It is the loadstar of African liberation politics in southern Africa, but has also become an important training ground for the construction of a new, Africanised, ANC-aligned bureaucracy in South Africa. It is this functional role, combined with a broad legitimation of the ANC as the ruling party, that has defined the university’s role in the post-apartheid era. Arguably, however, the reconstruction of UFH as a ‘heritage institution’ for African nationalism has discouraged its staff and students from contributing to the debates about political renewal and ideological reorientation within the ANC and liberation movements more broadly.

In order to maintain and expand on its historical legacy, UFH has also embarked on a broad programme of opening up recruitment to staff and students from across Africa. In 2016, the majority of its senior academic staff (including professors and faculty deans) and postgraduate students were not South African nationals. This has created an ideological fault line at Fort Hare, specifically in the context of the ongoing protests across South African universities relating to student fees and broader transformation issues. Indeed, there has been growing agitation and discontent in the UFH student body at the failure of the university to provide new trajectories into the middle class, beyond the bureaucracy which is now becoming oversubscribed. Furthermore, students have made demands for a kind of fee structure, admissions policy and service that would benefit young black South African nationals, rather than students from other African countries.

3.2. Training of the labour force

A basic assumption following the independence of African nations in the 1960s and 1970s was that universities were expected to be key contributors to the human resource needs of their countries, and particularly in relation to the civil service and the professions. This was to address the acute shortages in these areas that were the result of the gross underdevelopment of universities under colonialism. Fort Hare, in contrast, started with theological education and training. But, as apartheid tightened its ideological grip in the 1960s, the university became more of a ‘state tool to build a nation within a nation’ (Thakrar, Citation2017); in other words, it would produce graduates who could serve the needs of the homeland in which it was situated, training administrators (for the public service rather than for business) and teachers and nurses (rather than doctors or engineers).

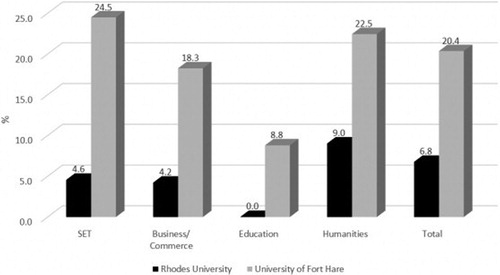

By 1994, the enrolment shape of UFH was pretty much how the apartheid government had intended it, with a high proportion (62%) of students enrolled in humanities and teacher training programmes, leaving 24% in science and technology and 14% in business and management programmes. Significantly, not much has changed in the pursuant years. Following the merger with the East London campus of Rhodes University in 2004, figures show () that the greatest increase in graduates has occurred in the humanities and social sciences which, in 2014, constituted 44% of the total output. While the number of graduates in science, engineering and technology (SET) grew at a healthy rate of around 13% over the period, they still only constituted a quarter of the total. Business and management sciences had the highest average annual growth rate, but, along with education, still constitute the smallest proportion of the graduating class.

Table 1. Total graduates by fields of study: 2004 and 2014.

A study comparing Rhodes University and UFH graduates (2010–11) regarding study choices and employment transitions (Rogan & Reynolds, Citation2015) is very revealing. At Rhodes, about 60% of graduates who intended to study a discipline within SET, successfully completed a degree in SET. Among UFH graduates, just less than half (48%) of those who intended to obtain a SET degree, did so. Rhodes graduates were also significantly more likely than UFH graduates to complete the degree in which they originally intended to enrol. Fort Hare graduates who changed their study category between matric and university graduation, switched to humanities. The main reason provided for changing from the initial intended course of study differed between the groups. Among UFH students, 32% indicated that their marks were not good enough to gain entry or to complete their studies. Financial pressures were also a consideration, with 7% indicating a perceived lack of jobs in their initial choice of study, or a lack of scholarship opportunities (14%). By comparison, 48% of Rhodes graduates reported loss of interest as their motivation for switching their course of study.

With regard to the transition from university to the labour market, the two most striking findings of the study were the differences in unemployment rates and employment sectors. On average, the unemployment rate among Rhodes graduates was 7%, while that among the UFH graduates was almost three times higher (20%). Contrary to popular belief, the lowest unemployment rate for both groups was in education. For UFH students the highest unemployment was SET while for Rhodes it was the humanities. This certainly raises many labour market and quality of programmes issues.

The most dramatic finding in relation to employment was that the vast majority (73%) of Rhodes graduates were employed in the private sector, while 67% of UFH graduates found employment in the government sector. These findings imply that UFH has not shaken off its traditional African and homeland mission of predominantly training students for work in government. There are exceptions, such as the award-winning accountancy training programme in East London, but it is difficult to expect UFH to change its profile and brand unless it can offer programmes in medicine, engineering and regional niche areas ().

Figure 1. Broad unemployment rates (as of 1 March 2014), by field of study. Rogan and Reynolds (Citation2015).

3.3. The production of scientific knowledge

Castells (Citation2001) argued that the major area of underperformance of universities in Africa is in the research or ‘generation of new knowledge’ function. Tellingly, Africa is at the bottom of almost every indicator-based ranking and league table in science and higher education (Zeleza, Citation2016). A recent assessment of eight flagship universities in sub-Saharan Africa concluded that while these institutions had done well in elite selection and training, they had not been very effective in developing social legitimation or cohesion (Cloete et al., Citation2015b). And, with the exception of the University of Cape Town, they had fared poorly in terms of knowledge production (i.e. doctorates and research outputs) (ibid.).

Prior to 2006, UFH had minimal interaction with national policy frameworks and knowledge production initiatives, and research-facilitating structures were fragmented and uncoordinated across the institution (Cloete & Bunting, Citation2013). This situation changed after 2006 when UFH started a process of developing a new strategic plan in order to avoid being classified as a low-ranked teaching university in South Africa. The shifts that occurred were underpinned by a realisation that research capacity development for academic staff and postgraduate students should be a priority. This was connected to the centralisation and strengthening of research administration, which allowed for a greater sense of planned facilitation, monitoring and evaluation of research efforts. Further interventions were the development of a strategic research plan for 2009–16, the restructuring of the research management division, and the identification of key research funders and possible niche areas. In addition, an incentive scheme for research outputs was put in place which included $2000 for each accredited research article, $2000 for each masters graduate, $6000 for each doctoral graduate, and $1500 for winners of the vice-chancellor’s senior and emerging researcher medals.

As the figures below show, these strategic interventions have supported and encouraged the development of UFH’s knowledge production function from its very limited and humble beginnings. For the purposes of this paper, high-level knowledge production is conceptualised in terms of inputs and outputs (Cloete et al., Citation2015a). Inputs include the seniority and qualifications of academic staff employed by a university, as well as doctoral enrolments. The outputs include doctoral graduates, and research publications in the form of journal articles and published proceedings of research conferences. Senior academics (professors, associate professors and senior lecturers), and especially those with PhDs, are important for knowledge production since they are qualified to supervise students. They are also much more likely to publish (see e.g. Cloete et al., Citation2016).

Over the period 2006–14, the number of senior academics at UFH increased from 105 to 140, an annual increase of 4%. Despite this improvement, the proportion of senior academic staff (42%) falls short of the target (60%) for traditional universities. There was also a substantial increase in the number of academic staff with doctorates, from 54 in 2006 to 142 in 2014. This constitutes an average annual change of around 13% which is much higher than at a comparative university such as Rhodes (3%). However, since UFH started its growth from such a low base, it still did not quite meet the target (50%) for traditional universities for academic staff with doctoral degrees.

UFH also expanded its doctoral student enrolments rapidly over the period, at an average annual rate of 24%, from 90 doctoral enrolments in 2006 to 477 in 2014. This growth rate was, once again, much higher than that of Rhodes, which averaged at almost 10%. Furthermore, by 2014, UFH had met the university target of 3% of enrolments in doctoral programmes. Doctoral graduates also grew rapidly from only nine in 2006 to 66 in 2014, an average annual increase of just over 28%.

At the national level, research outputs are incentivised as part of the Department of Higher Education and Training’s (DHET) revised funding framework, which was implemented in 2006. The funding formula does not set fixed prices for research outputs; instead, it divides the research budget allocation between universities on the basis of their share of the total outputs in a given year. As such, in 2014, the incentives for UFH were $9000 per research masters graduate, $26000 per doctoral graduate, and $9000 for research publications per unit. Based on various analyses of South Africa’s research output, Mouton and Valentine (Citation2016) report that the revised DHET funding framework, along with some other factors, has resulted in steep and sustained increases in the number of research publications across the higher education sector.

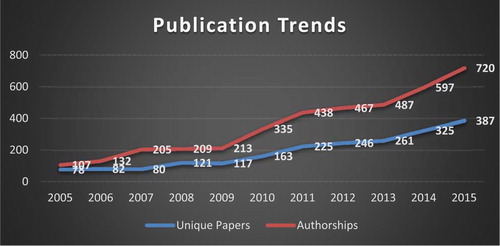

As shows, since 2005 there has been an annual increase of around 18% in publication outputs at UFH which, albeit starting from a low base, is one of the steepest in South Africa. This is due to an extraordinary increase in research article production, especially over the last three years, reaching a total of 387 papers in 2015 compared to 78 in 2005. UFH’s average annual growth rate in research publications over the past 10 years has been a very respectful 9%. As a result, UFH could be ranked seventh overall on the ‘weighted research output’ indicator (Mouton & Valentine, Citation2017).

Figure 2. Publication trends at the University of Fort Hare. Mouton and Valentine (Citation2017).

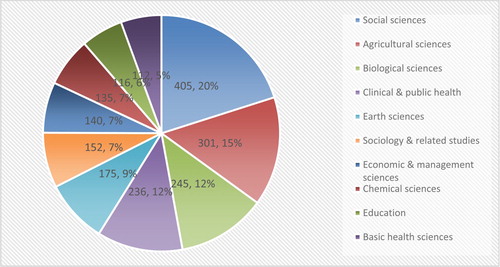

shows that the majority of UFH’s publication outputs are in the social sciences, followed by agriculture and the biological sciences – a surprising development given that agriculture, biological sciences and public health have traditionally been UFH’s strongest fields. If one looks at changes in the number of publications in specific fields from 2007–15, it can be seen that while agriculture remained somewhat constant (from 111 to 131), the biological sciences decreased (from 40 to 26). The most dramatic increases were in fields such as the chemical sciences (13 to 81), economic and management sciences (1 to 74), education (12 to 78), sociology and related studies (0 to 156), and ‘other’ social sciences (12 to 239). These are indeed extraordinary increases.

Figure 3. University of Fort Hare publication output by scientific field. Mouton and Valentine (Citation2017).

However, Mouton and Valentine (Citation2016, Citation2017) point out that the research publication totals cited above must be viewed with a measure of caution. The main reason is that Fort Hare’s totals include a large proportion of predatory journal publications. Journals are classified as ‘predatory’ when they are open access for the sole purpose of profit; solicit manuscripts by spamming researchers; have bizarrely broad or disjointed scopes or titles; claim extremely rapid response and publication times; publish markedly high numbers of papers per year; boast extraordinary and often fake journal impact factors; make false claims about where the journal is indexed; often have fake editorial boards or editorial boards that comprise a small number of individuals from the same organisation or country; and often include high-status scholars on the editorial board, without their knowledge or permission. In their analysis of the universities in the Eastern Cape, Mouton and Valentine (Citation2016) show that a quarter of all publications produced at both UFH and Walter Sisulu University could be classified as predatory, compared to only 2% at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) and less than 1% at Rhodes. In fact, out of all South African universities, only the Mangosuthu University of Technology had a higher proportion of predatory journal articles than UFH.

From 2005–11, UFH showed a clear trend towards increasing publications in the Thompson Reuters Web of Science (WoS), where, in 2011, publications in the WoS constituted more than 80% of all UFH papers (Mouton & Valentine, Citation2017). There has also been an increase in the number of UFH papers published in the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), an index that mainly caters for journals in the humanities and social sciences. In fact, by 2015 more UFH papers were published in the IBSS than in WoS journals. However, it is the IBSS index that is most suspect in terms of predatory journals: while the journals listed in the WoS are normally subjected to rather more stringent criteria of quality assurance, this is not the case for all journals in the IBSS. As Mouton and Valentine (Citation2016) argue, this is a trend that should cause concern as it may suggest that academics at UFH have changed their publication strategies to submitting increasing numbers of papers to journals that are perceived to be ‘easy and quick to publish.’

UFH also faces some demographic challenges in relation to publication outputs. Prime amongst these is that while 81% of UFH authors are black, only 31% of these are South African. Furthermore, of the top 10 most prolific authors, only two are South African. On a positive note, this is probably one of the highest proportions of internationalisation (specifically in terms of the rest of Africa) of authors at any South African university. In terms of gender, for the period 2005–15, 80% of all authors were male – one of the highest proportions of male-authored papers at any South African university. However, female representation has improved in recent years, most likely owing to the growth in the numbers of social science papers.

In summary, there has certainly been a concerted strategic attempt at the institutional level to boost research outputs in the form of staff capacity, doctoral enrolments and graduations, and publications. In terms of the DHET indicator of research productivity, which is the ratio between total research outputs (articles + conference papers + books + research masters graduates + doctoral graduates) in a given year, and the number of permanent academics in that year, UFH’s ratio of 2.15 places it in a band with the top seven research universities in the country.

Along with the University of Western Cape, UFH has been by far the most successful of the historically disadvantaged universities in strengthening the knowledge production function. In the process, this has contributed to increased government subsidies for masters and doctoral students and for publication output. And, by increasing its research outputs, UFH has been able to improve its external profile, as well as that of certain of its organisational units, and to attract more interest from funders for research grants. However, the system of increased government subsidies for knowledge outputs, together with institutional financial incentives, puts pressure on both institutions and individuals to over-report and overproduce. According to Harzing (Citation2005), there is considerable evidence internationally that increased publication outputs associated with direct financial incentives is associated with a reduction in quality (measured in terms of a decrease in citations).

In addition to the perverse effect of incentives, there is also pressure on young academics to publish quickly, both for promotion and for financial rewards, which makes them susceptible to predatory journals. A particular challenge UFH may have is that with an unusually high proportion of mobile academics (i.e. foreign academics without tenure), there is an even higher pressure to publish quickly, which is only exacerbated by incentives that are paid in US dollars. This also raises the question about the relevance or local/regional applicability of the knowledge produced – an issue which certainly warrants further investigation, particularly in light of Thakrar’s (Citation2017) report on the disengagement of UFH from its surrounding communities.

4. Conclusion

Fort Hare, like many universities around the world, is at the beginning of the next phase of its development. As such, it is confronted with contradictions and tensions that are both a product of its history and of its changing societal context locally, regionally, nationally and internationally.

UFH was established as part of an ideological (colonial Christian) project. This function became even more entrenched following the 1959 Extension of University Education Act when the imposed mission of the university was to forge a Xhosa ethnic identity and to produce functionaries for the Ciskei homeland. UFH resisted the anti-apartheid role by becoming a site of contestation against the apartheid regime through developing a very strong human rights culture, while still producing a mixture of politicians and functionaries.

However, since the transition to democracy, the unifying anti-apartheid ideology of the university has fragmented and the elite selection function is not as pronounced. In terms of the analysis of Castells (Citation2001) regarding the ideological apparatus function, in many post-independent African countries things unravelled very quickly as the universities, with competing aspirant elites, became cauldrons of conflicting values, ranging from conservative-reformist to revolutionary ideologies. The contradictions between academic freedom and political militancy, and between the drive for modernisation and the preservation of cultural identity, were detrimental to the educational and scientific tasks of the university. These new universities could not merge the formation of new elites with the ideological task of forging new values and the legitimation of the state, which is essential for development, and hence the universities and the development project failed (ibid.: 213).

Two other functions that are crucial for development are training and knowledge production. A daunting task for UFH was to move away from the enrolment shape imposed on it by the apartheid government. In 1994, a very high proportion (62%) of students were enrolled in humanities and teacher training programmes. Not much had changed by 2014 insofar as the greatest increase in enrolments was once again in the humanities and social sciences (44% of the total enrolments). While UFH has managed a steady increase in SET and business management enrolments, SET still only constitutes 25% of all enrolments and business management 15%. What this tells us about UFH’s training function is that although it is slowly shifting its enrolment profile, it is still trapped in the historical African and homeland path of preparing people for government, as the employment figures show (67%). And, with the looming slowdown in government employment, this will indeed be a serious challenge.

The most significant shift in UFH has been in the area of knowledge production which has been the result of making the restructuring of the institutional research architecture, capacity development for academic staff, and postgraduate students and research outputs, a priority. This followed a lengthy planning and consultation process led by the new Vice-Chancellor and resulted in a new strategic plan for the period 2009–16 (UFH, Citation2009).

In particular, from 2008, UFH increased the number of senior academics, academics with doctorates, doctoral student enrolments and graduates and, even more dramatically, publication outputs. Its share of research outputs for the whole South African university system showed the third highest improvement of all universities in the country. Yet, casting a shadow over these achievements is the spectre of the high proportion of publications in predatory journals and the social sciences, which raises questions about the relevance of the university’s research outputs to development in the Eastern Cape and the country as a whole.

An even more serious obstacle for UFH is its poor financial health. Income from state sources include block grants generated by a subsidy formula, and earmarked grants for specific purposes such as physical infrastructure development. The majority proportion of block grant funding is generated by full-time equivalent student enrolments, which are, for subsidy purposes, weighted by field of studies and qualification level. According to Bunting (Citation2015), government planning decisions on Fort Hare’s student shape and size have had a major impact on the block grant it receives; specifically, insofar as these decisions have resulted in the university remaining primarily a humanities, social sciences and teacher training university, with low proportions of students in SET, business and management programmes. As a consequence, UFH’s annual block grant has been substantially lower than that of a similarly-sized university with greater proportions of enrolments in these latter fields. In addition, UFH has not been able to supplement its state income by increasing student fees or effectively collecting outstanding student debt. While UFH did reasonably well in obtaining designated or restricted research grants, which averaged R127 million per annum between 2000 and 2008, its private or undesignated donations were, over the same period, a worryingly low annual average of R6 million (ibid.). Considering the large number of illustrious alumni, this suggests that the ‘Fort Hare brand’ has not been widely supported by donors. One of the effects of its low level of third-stream income has been that Fort Hare has had little or no scope to fund infrastructure developments not approved by government.

With regard to East London, it could be argued that just as the government oscillated between developing the Alice or East London campuses, so too has Fort Hare. East London, unlike Port Elizabeth, does not have a stand-alone university; it is just a reservoir of students for competing higher education institutions (Cloete et al., Citation2004). Internationally and in South Africa, as other articles in this volume show, there is now a growing movement to link universities to city (metropolitan) development. With serious questions being raised about the sustainability of UFH in its current form, at both the Alice and East London campuses, the issue of a city university embedded and engaged in the metropolitan growth district must be explored again. East London and UFH need each other, but not under the present arrangements in which the main contact seems to be with city landlords, who rent blocks of flats and old hotels at high prices to UFH for the accommodation of disadvantaged students, and leave UFH with the task of collecting rentals directly from the students.

However, for a university to effectively engage with and contribute to city development, it requires relevant academic capacity. The assessment of UFH’s functions and performance raises serious doubts about the institution’s capacity to engage, for example, with the health issues of the metro, the global motor vehicle industry, and the East London industrial development zone. Looking at other universities in South Africa which too are grappling with contradictory functions, a university such as Stellenbosch shifted from being largely a producer of apartheid ideology and civil servants to one of the best-performing universities in the country (Cloete et al., Citation2015c). Key to this transformation was deliberate internationalisation driven by strong medical and engineering faculties, as well as agriculture linked to the international wine business. In contrast to UFH, NMMU (the result of a merger between a historically white university, a historically black university and a technikon) has done very well in terms of performance and engagement with the city.

In Castells’ (Citation2001) terms, while the elite and ideological functions have weakened, the training and knowledge production functions have strengthened. However, challenges remain: in terms of training, there needs to be a shift to producing students who will be competitive in the private sector labour market; regarding research, predatory journals are a serious concern. For UFH to develop a more sustainable strategic plan that also contributes to the development of East London, the university will not only have to rethink its model of the ‘traditional’ university, but it may have to revisit the original NWG plan of a multi-campus university in the East London metropolitan area, with a medical school and engineering. However, as Castells (Citation2001) pointed out, this will require both institutional capacity and national system support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Tracy Bailey http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2984-814X

References

- Badat, S, 2004. Transforming South African higher education 1990–2003: Goals, policy initiatives and critical challenges and issues. In Cloete, N, Pillay, P, Badat, S & Moja, T (Eds.), National policy and a regional response in South African higher education, pp. 1–50. James Currey, Oxford.

- Bank, A & Bank, L, eds. 2013. Inside African anthropology: Monica Wilson and her interpreters. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Bunting, M, 2015. Financial characteristics of the non-profit organisation: Theory and evidence for the assessment of the financial condition of South African public universities. PhD thesis, Rhodes University, South Africa.

- Castells, M, 2001. Universities as dynamic systems of contradictory functions. In Muller, J, Cloete, N & Badat, S (Eds.), Challenges of globalisation: South African debates with Manuel Castells, pp. 206–23. Maskew Miller Longman, Cape Town.

- Cloete, N & Bunting, I, 2013. Challenges and opportunities for African universities to increase knowledge production. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris.

- Cloete, N & Muller, J, 1998. South African higher education reform: What comes after post-colonialism? Centre for Higher Education Transformation, Pretoria.

- Cloete, N, Pillay, P, Badat, S & Moja, T, 2004. National policy and a regional response in South African higher education. James Currey, Oxford.

- Cloete, N, Bunting, I & Maassen, P, 2015a. Research universities in Africa: An empirical overview of eight flagship universities. In Cloete, N, Maassen, P & Bailey, T (Eds.), Knowledge production and contradictory functions in African higher education, pp. 18–31. African Minds, Cape Town.

- Cloete, N, Maassen, P, Bunting, I, Bailey, T, Wangenge-Ouma, G & Van Schalkwyk, F, 2015b. Managing contradictory functions and related policy issues. In Cloete, N, Maassen, P & Bailey, T (Eds.), Knowledge production and contradictory functions in African higher education, pp. 260–89. African Minds, Cape Town.

- Cloete, N, Mouton, J & Sheppard, C, 2015c. Doctoral education in South Africa: Policy, discourse and data. African Minds, Cape Town.

- Cloete, N, Bunting, I & Van Schalkwyk, F, 2016. HERANA phase 3: Changes and trends. Paper presented at the HERANA phase 3 meeting, 21–23 November 2016, Franschhoek, South Africa.

- Harzing, A-W, 2005. Australian research output in economics and business: High volume, low impact? Australian Journal of Management 30(2), 183–200. doi: 10.1177/031289620503000201

- Higgs, C, 1997. The ghost of equality: The public Lives of D.D.T. Jabavu of South Africa, 1885–1959. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio.

- Kerr, A, 1968. Fort Hare, 1918–1948: The evolution of an African college. Shuter & Shooter, Pietermaritzburg.

- Massey, D, 2010. Under protest: The rise of student resistance at the University of Fort Hare. Hidden Histories Series. Unisa Press, Pretoria.

- MoE, 2002. Transformation and restructuring: A new institutional landscape for higher education. Ministry of Education, Pretoria.

- Mouton, J & Valentine, A, 2016. University of Fort Hare: A bibliometric study. Report commissioned by the Centre for Higher Education Trust, Cape Town.

- Mouton, J & Valentine, A, 2017. The extent of predatory publishing in South Africa. South African Journal of Science forthcoming.

- NCHE, 1996. An overview of a new policy framework for higher education transformation. National Commission on Higher Education, Pretoria.

- Rogan, M & Reynolds, J, 2015. Schooling inequality, higher education and the labour market: Evidence from a graduate tracer study in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Paper presented at the International Council on Education for Teaching (ICET) 59th World Assembly, ‘Challenging Disparities in Education, 19–22 June 2015, Tokushima, Japan.

- Thakrar, J, 2017. University-community engagement as place-making? A Case of the University of Fort Hare and the town of Alice. Unpublished paper.

- UFH, 2009. Strategic plan 2009–2016: Towards our centenary. University of Fort Hare.

- Zeleza, P, 2016. The role of higher education in Africa’s resurgence. Eric Morobi Inaugural Memorial Lecture, 15 October 2016, University of Johannesburg.