ABSTRACT

The concept of what a per diem is and who should receive one is a complex idea that, within the development context, can either support or hinder the achievement of development projects’ goals. This paper seeks to explain the evolving nature of per diems and their use within the development context; explore how they serve as barriers or enablers in achieving project goals; and touch on their impact on the development project cycle. Through a 3-year-long internationally funded development programme in Malawi and South Africa, the authors compare lessons drawn from their experience with existing literature to determine the practicalities of paying per diems and address the question: To what extent do per diems support or hinder international development projects?

1. Introduction

The term ‘per diem’ (henceforth per diem/s) has Latin origins that can be traced back to 1809. Its meaning of ‘by the day’ refers to an amount determined in advance to act as a daily allowance. Its original application was intended for sales representatives and civil servants to cover expenses while travelling during extended periods of time. The per diem would include payment from a wider variety of role-players, such as employers more generally, as well as development agencies to cover approved employee expenditure (Vian et al., Citation2013).

Per diems are relevant to the field of international development in two ways. First, employees of international donor agencies receive per diems for trips to field-sites, for instance. This is in line with the more traditional use of per diems to make provision for travelling expenses. However, such payments have been problematised as they often vastly exceed what staff from local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) receive. Second, per diems are also used in-country in international development projects to cover travel and food expenses of civil servants and project beneficiaries. This has been extended as a way in which to compensate beneficiaries for participation in international development projects.

How and why per diems are paid in development projects is worth examining for both the macro- and micro-level impacts. At a macro-economic level per diems can be viewed within the context of ‘huge sums of money flowing in and out of Africa in the name of research and implementation’ (Conteh & Kingori, Citation2010:1554). This is in part because ‘an increasingly considerable portion of public spending is allotted to allowances and per diems, usually in connection with seminars and workshops. This is especially the case as capacity building is a central concern of development efforts notably in Africa’ (Nkamleu & Kamgnia, Citation2014:5). Examples of scale mentioned in the literature include that in 2009 the Government of Tanzania spent USD 390 million on allowances (Vian et al., Citation2013). On a more micro-level, the payment of per diems raises the question of individuals’ incentives to participate in projects, especially as a result of the disproportionate amounts paid to them: a study conducted in two districts in Burkina Faso found that per diem income exceeded health workers’ salaries (Ridde Citation2010), while in Mozambique health workers that participated in a 3-week provincial workshop received the equivalent of 18-months’ salary from the development agency (Bryce et al., Citation1993).

Our interest in the topic of per diems stems from our 3-year programme funded by an international donor to build civil servants’ capacity in the use of research evidence in decision-making in South Africa and Malawi.Footnote1 Our experience of project implementation in South Africa was very different to working in Malawi where the topic of per diems was frequently discussed at various times during our project inception phase and year of implementing it there (2014–15). This emphasis on the payment of per diems has sparked our interest in the experience of other development projects working in Malawi specifically and elsewhere in Africa. We distinguish unequivocally between, on the one hand, per diem systems as a rational and justified means of cost reimbursement to staff when travelling away from normal duty station, which is an idea we support; and, on the other hand, how the system is used for purposes beyond its original intention, which we do not condone. This paper addresses the latter – the practices and potential malpractices of per diem payment and the implications of this for how projects are designed and implemented.

This paper explores the ways in which per diems can act as enablers and barriers in international development projects, affecting different aspects of the project lifecycle at different times. The need for further discussions on per diems is supported by the literature where a shortage is mentioned (Vian et al., Citation2013) as well as ‘that this issue has rarely been raised globally, as though discussing it were taboo in the development assistance community’ (Aiga, Citation2012:621).

2. Use of per diems in the African context

In order to understand the payment of per diems it is necessary to acknowledge their complexity, for example what constitutes a per diem, how they apply to different sectors, the extent of their use, and what purpose they serve (Conteh & Kingori, Citation2010). The payment of per diems can fulfil a number of different functions for the organisation paying them: they serve to cover travel-related expenses (Søreide et al., Citation2012; Vian et al., Citation2013; Nkamleu & Kamgnia, Citation2014); they encourage attendance at professional development courses or meetings (Nkamleu & Kamgnia, Citation2014) and the uptake of activities that might otherwise be difficult to carry out (Vian et al., Citation2013); they act as financial incentives that increase the job satisfaction of employees (Nkamleu & Kamgnia, Citation2014); and they allow an organisation to streamline its financial accounting systems (Søreide et al., Citation2012) by ‘simplifying administration by eliminating the controls needed in a system of reimbursing actual costs’ (Søreide et al., Citation2012:6).

Allowances can be distributed in different ways. Comparative work across Tanzania, Malawi and Ethiopia demonstrated this: for example, in Tanzania

… some allowances are linked to a specific position or situation, referred to as remunerative allowances, and include for example ‘disturbance allowance’ (if relocating), outfit allowance and housing allowance. Other allowances are discretionary benefits, often referred to as duty-facilitating allowances, and include overtime and special duty allowances, honoraria for outstanding performance and sitting allowances … (Søreide et al., Citation2012:18).

However, although some overlap exists, in Malawi distinction is made conceptually between the intended functions of allowances: ‘income-enhancing or remunerative allowances … and performance or work-facilitating and work-enhancing allowances’ (Søreide et al., Citation2012:40). Per diem rates can also vary by location, by sponsor and by staff level (Vian et al., Citation2013). There are different views on whether it is fair that rates vary by seniority (Vian et al., Citation2013) as the (mis)use of per diems by more senior staff is sometimes highlighted less as their power obfuscates this (Conteh & Kingori, Citation2010).

It is the income-enhancing element of per diems that receives some attention in the literature because ‘while these allowances are only meant to be compensatory, they tend to assume the character of additional salary payment in countries where salary levels are generally low … [and] may contribute significantly to total income’ (Søreide et al., Citation2012:3). When civil servants in Uganda and Tanzania were surveyed three-quarters of the sample saw allowances as equally important to a basic salary for their total income, while 13% were of the view that allowances were much more important than salaries (Therkildsen & Tidemand, Citation2008). However, a cautionary note is necessary when speaking about low salaries and what the comparators are as civil servants are sometimes more well-off than other professional groupings, such as those working in NGOs for instance. Such income supplementation does not exclusively apply to civil servants, and examples exist of it being an important means for health workers who receive low salaries or who experience delays in salary payments to supplement their income (Roenen et al., Citation1997; Chêne, Citation2009). If per diems go hand-in-hand with the topping up of salaries it is apt to ask what the implications of the institutionalisation of per diems are for salary levels. Such longer-term implications might include the undermining of the fair payment of salaries (Ridde, Citation2010; Scotland Malawi Partnership, Citation2014). A final aspect that might lead to increases in requests for the amount of per diem payments received in order to top up salaries is the imbalance between per diems allocated to international NGO staff and/or donor aid workers and local staff to attend the same event, for example

… a local person might receive USD 10 to attend a workshop, but someone from the WHO or UN attending the same workshop might receive close to USD 300. This might further reinforce power imbalances and also make local people ask for increases in per diems. If the problem is to be examined, all of the actors and the structural context that allow it should be examined … (Conteh & Kingori, Citation2010:1554).

Differences of opinion exist on what per diems might mean for how development projects are implemented and for the field of international development more generally. More critical views argue that per diems undermine employment rights, good governance systems and project implementation (Scotland Malawi Partnership, Citation2014). Openness is emphasised as per diems are seen as going ‘to the heart of what development projects aim to achieve’ (Aiga, Citation2012:620). The payment of per diems is not necessarily equated with corruption as regulatory frameworks do exist in some countries, although not all (Conteh & Kingori, Citation2010). Furthermore, economists might argue that individuals are merely maximising their personal utility (Conteh & Kingori, Citation2010). However, when asking whether per diems pose a challenge in the implementation of development projects it has been pointed out that who poses the question is important – Western public health professionals have raised concerns, but it has to be asked whether people in developing countries also perceive the negative effects of per diems for development projects (Vian et al., Citation2013).

3. Approaches to studying the topic

This paper draws on three main sources, the first of which is the existing literature on per diems as they relate to the field of international development. This was identified through searching academic peer-reviewed databases and locating grey literature on the topic.

Drawing on the advice in the existing literature on per diems, the paper also attempts to provide the perspectives of different actors in the development field (Vian et al., Citation2013) by drawing on 12 interviews conducted over a 2-month period between February and April 2016. These included people that have played different roles in development projects, for example those who have funded projects, been implementers of projects, or who have been beneficiaries of projects in Malawi specifically, and some also in other African countries.

Finally, the paper draws on the first-hand experiences of the authors who are part of a larger team that has been implementing a 3-year internationally funded programme to support government capacity to use research evidence in decision-making in South Africa and Malawi. Although our experiences are only observational and anecdotal, they add value in testing how our experience resonates with the existing literature and can add to what is already known and documented about the role of per diems in international development. The interest in writing this paper stems particularly from project conceptualisation and implementation in Malawi (2014–15) as per diems were a component that affected the project. Our programme in Malawi was implemented through a local NGO with support from South Africa in the form of frequent field visits. Following the guidelines from our funders our programme did not pay what is known as ‘sitting allowances’ – payments in order to attend workshops or mentorship opportunities. In line with the interpretation of per diems as reimbursement for travel and for meals, programme participants were reimbursed/received an allowance amount agreed between different international funders and the Malawi government. Despite following what were agreed guidelines, programme implementation showed, as highlighted elsewhere in the paper, that although these amounts were adequate to cover real expenses they were not always regarded as sufficient. This influenced programme implementation and piqued our interest in this topic.

All data were analysed using a thematic analysis framework (Boyatzis, Citation1995).

Whilst this paper only looks at per diems in the context of Africa, and specifically Malawi, it adds to the existing body of knowledge by drawing together the views of different role-players in the development field, for example international donors, local NGOs, civil servants. In addition, where much of the existing literature on per diems focuses on the health sector (Aiga, Citation2012; Vian et al., Citation2013) this paper takes a broader view and looks at per diems in areas outside of health. Finally, as set out in later sections of this paper, our analysis of the data indicates that per diems affect all aspects of the project planning and management cycle, which is a novel contribution to the literature on per diems.

4. Per diems as an enabler in development projects

The literature suggests that per diems can have benefits on three levels – individual, organisational and at the level of international development, although these levels are not mutually exclusive. The personal benefits of per diems focus on two dimensions. The first, and most predominant, relates to per diems acting as a top-up to salary, for example providing additional salary for paying household expenses (Aiga, Citation2012; Vian et al., Citation2013), allowing families to save for bigger expenses and to pay back loans (Vian et al., Citation2013). Making more money available to individuals where salaries are low contributes to poverty reduction (Vian et al., Citation2013). Receipt of per diems also has the potential to increase the personal motivation of staff (Vian et al., Citation2013). Organisational benefits of paying per diems relate to facilitating work getting done by paying the necessary travel expenses, increasing the knowledge base of staff in the organisation by encouraging attendance at training, being a way in which work is recognised, increasing staff productivity and motivation (Vian et al., Citation2013), and increasing spending efficiency by controlling what employees can spend (Vian, Citation2009). The perceived benefits of per diems in the development sector and to development agencies are not dissimilar to what has been mentioned above in relation to personal and organisational benefits and again speaks to the idea of incentives/motivations to participate in development projects and to ways of facilitating the uptake of training opportunities. Again, people are more likely to attend optional meetings or training where they will learn new professional skills if their expenses are reimbursed (Vian, Citation2009; Nkamleu & Kamgni, Citation2014). However, per diems also help development agencies to smoothly implement in-service training programmes by ensuring that a planned number of trainees attend (Aiga, Citation2012).

The role of per diems as incentives or motivating factors to participate in development projects was also a theme that emanated from the interviews we conducted, although ways were mentioned that this could be mediated. The payment of per diems is a factor that could be influential when project buy-in is negotiated:

People have been exposed to other programmes prior to this one … they benchmarked our programme to the previous programmes they’ve been involved in. (Respondent, International Development Programme)

Sometimes if people know there is this event [and] there will be allowances, they’ll come. Because they want to get their allowances and the allowances are given at the end. That can be enabling … they take it as part of income, but I think their salaries are too low. (Respondent, Local NGO)

It’s been a source of conflict and issues … on the other hand again it makes sure all the work gets done. (Respondent, Local NGO)

Who does it [paying allowances] reward? It rewards you – the project manager. (Respondent, International grants-making NGO)

The incentive value of per diems is particularly relevant in the context of a lot of donor activity in a particular setting, people having limited time, and donors in a sense vying for the same audiences.

People … will have a number of projects they’re working with. Those projects offering the greatest incentives, they’ll be motivated to work with them … we manage to deal with that by working long enough in those countries and having trust in those partners. (Respondent, International Development Programme)

… should not be done on the backs of poor people. (Respondent, International grants-making NGO)

If I am asking slum dwellers who are structurally unemployed, structurally malnourished to come to a workshop to talk to me about what’s going on in their community, the very least I can do is recognise the higher opportunity costs to that poor person who’s just on the edge of surviving. (Respondent, International grants-making NGO)

People are already paid in their respective jobs. They get their salary for doing that. It’s part of their work. (Respondent, Local NGO)

The actual functions of the job that you are doing for a [development] partner for me is like an added function. Because … I have my own job description as a government official … So when a project comes and says for example … you are an … officer for the project, which means I have to allocate maybe 20 percent of my time doing the project jobs … I need to be paid for that … So because the rules of the game are that you cannot be paid a salary – you can’t get two salaries – but I need to get something that can help me to work better in that kind of environment. (Respondent, Government)

It used not to be like that … But now things have changed. I don’t know whether it’s due to the coming of several NGOs and different types of funding … (Respondent, Local NGO)

With the NGOs bringing in the allowance culture, what came in was that we saw that as people did not have money, they saw that there were more donors, more projects, people paid and they seemed to be motivated … the culture has come to stay. (Respondent, Local NGO)

It’s a diversion to say ‘wow we can’t have these workshops unless we pay these guys. They’re demanding airfare, they’re demanding USD 30 a day in sitting fees because that’s what donor X pays’ … They just know the game. They know that you are sitting there with a donor-driven project where you’ve promised the moon to the donor – why not charge you for their time? … [It is about] getting what they have to do versus what you the outsider has to do in order to make donors happy [and] keep your money flowing … So do I … get all moralistic about it or do I see that it’s a larger system that forces people to be less than their best. (Respondent, International grants-making NGO)

5. Per diems as a barrier in development projects

The ways in which per diems act as barriers in the development context are highlighted in the literature and can be grouped around three general areas.

The first of these areas is that per diems can lead to the abuse of the donor funding system. This abuse can take a number of different forms such as the falsification of records in order to obtain payment of more per diems (Vian, Citation2009), delaying duties to clock overtime, double-dipping, exaggerating number of days worked, skimming days (doing work in less time but keeping the full per diem), workshop fraud (falsifying participant lists), and so on (Vian et al., Citation2013).

The second way in which per diems can act as a barrier relates to human resources and includes aspects such as how people allocate their time and what acts as intrinsic or extrinsic motivating factors. Per diems can create conflict in teams between those receiving per diems and those who are not (Vian et al., Citation2013). Per diems can affect productivity and can lead to task shifting, for example staff who do not have work opportunities where per diems are paid become less productive or avoid tasks that do not have per diems linked to them (Vian et al., Citation2013). Per diems and other allowances have been shown to distort human resource management systems. This happens when staff move their focus from routine tasks to workshop attendance or other programme-specific activities to which per diems have been allocated (Hanson, Citation2012). Just as per diems encourage senior managers to attend training instead of sending their subordinates, the incentive of per diem revenue encourages high-level government officials to attend meetings and conferences rather than fulfilling administrative tasks that would require time at their desks. For example one government official in Ethiopia claimed that donor organisations were out-bidding each other, paying higher and higher per diems and drawing staff away from their jobs (Grepin, Citation2009). The payment of per diems also affects people’s norms and intrinsic motivation for performing certain tasks: people are perceived as reluctant to do even the smallest tasks without receiving a per diem (Jack, Citation2009; Vian et al., Citation2013). Finally, the payment of per diems can have an effect on workforce retention. The argument here, specific to projects in the health sector, is that in-service training does not lead to retention in the health system, but people change career paths and instead want to work for international development organisations, while international development organisations see such training as a recruitment opportunity (Aiga, Citation2012).

Third, per diems can act as a barrier in the effect that it can have on services or development outcomes. As an example, per diems can have a geographic effect on the quality of services provided as it tends to be staff from urban areas that capitalise on training opportunities at the expense of their rural counterparts (Aiga, Citation2012). The payment of per diems furthermore inflates the cost of services and therefore does have an effect on the value-for-money component of development (Søreide et al., Citation2012). Another example of inflated costs relates to the discussion around where training programmes are hosted. An argument is made that training or meeting participants can focus better if the meeting is held off-site, although some evidence suggests that residential training programmes are no more effective than non-residential programmes, yet residential programmes may cost a lot more due to the expenses of accommodation and allowances. An example of this is Zambia where residential training in child health management costs twice as much as non-residential training, yet skills and knowledge of participants tested at three and six months after training were about equal (Mukuka, Citation2004). The payment of per diems also has an effect on who attends workshops and that can have an effect on how the training received translates into the development outcomes. Sometimes people attend workshops unrelated to their work targets or more senior people attend them in order to collect per diems (Vian, Citation2009). Capacity-building is therefore affected by resultant poor application of learning (Aiga, Citation2012). It is also not unusual for development agencies to engage in price competition to get the participants they need when conducting training on the same day (Respondent, International grants-making NGO), and although such competition might not be negative per se, it could disproportionally inflate the budgets of development projects.

Data from the interviews and from our own experience match the barriers discussed in the literature, but also point to additional ways in which per diems can act as a barrier. Although some of the interviews hinted at the abuse of the system (for example asking for lunch allowances when a meeting was not held close to lunchtime or deliberately organising meetings close to lunchtime in order to get a lunch allowance), more interviewees referred to inconsistencies in the way in which the payment of per diems is managed as a barrier. There are rules and guidelines which help manage the payment of per diems, both internal policies for donor agencies and in-country agreements between governments and donors. However, how these guidelines are managed can act as a barrier to implementing development projects because although governments and donors might have agreed rates, some civil servants privately do not agree with these rates, or rates differ between donors and between donors and government.

You’ll find yourself invited to a government activity … you may find something different … and they’ll say ‘no we’re following USAID regulations because this is USAID money’ … (Respondent, Local NGO)

I know recently in Malawi the government released a circular … to say ‘no allowances’ … You’ll find some government officials have said in some meetings that I was attending … ‘OK, you go ahead with [implementing] this circular … You won’t see us – we’ll simply tell you we are busy’. (Respondent, Local NGO)

Government [and] the donors issue their stances on allowances from time to time. Now there are times where government and donors seem to differ in defining the allowances to be paid … There are times when the donors even among themselves, you’d find [differences in rates] … and it has really been impacting on implementation … because the culture has come to stay, if you come and don’t want to provide allowances like another organisation does, people will shun what this organisation is doing. (Respondent, Local NGO)

It depends on how people might look at it: it might create a culture of saying that you can only participate in something if you are paid for it. (Respondent, Government)

For me it looks like a culture … a learned culture … so to deal with this culture it’s difficult because the beneficiaries have been exposed to this way of doing things in terms of managing this kind of culture … And if we give them [per diems], we have to give more [money than other projects]. (Respondent, International Development Programme)

Personally I am against per diems as a secondary form of remuneration – they have negative incentive effects where you end up with people who attend events or processes because of the money and not for the cause. This is a tough challenge and environment to operate in … If nobody attends [an event] because there is no per diem then it is a good indicator of the poor relevance and importance of the meeting or process in the first place. (Respondent, International Donor Agency)

If you don’t have money to give them [beneficiaries] … then what happens? They will not come. (Respondent, Local NGO)

They [per diems] are massively destructive of projects. All of our donors expect value for money … the biggest cost we have is around incentives … and per diems. (Respondent, International Development Programme)

As has been mentioned there are positive impacts of per diems from a project management perspective in the conceptualisation and implementation phase of a project. However, when misused, the consequence of a per diem becoming a means through which leverage is created, where individuals consider per diems as a bargaining tool and threaten the successful completion of a project, one must consider whether they are worth their weight in gold. The implementation and reporting stage of a project can become somewhat precarious. The implementation of a project can be derailed by poor or non-participation of actors, consequently reporting on project goals and objectives as well as effective measuring and evaluating of a project is brought into question.

6. Analysis and reflection on the effect of per diems on the entire project cycle

A summary of the literature, reflection on our own experience, and interviews with others working in the field of international development illustrate that per diems are enablers in various ways and can act as barriers in other ways as discussed above. Per diems act as enablers in that they are extrinsic motivating factors for people to participate in development projects and therefore facilitate development efforts. In this sense they have become part of the bigger context in which development takes place and in some ways standard development practice. The argument here is that it is ethical to pay people for their time and not to run projects that might indirectly exploit people. But per diems also act as barriers in the development process as they lead to an abuse of the donor funding system, negatively impact on people’s motivation and the projects people participate in, which in turn affects development outcomes. The literature also speaks to various context factors that facilitate the existence of the system, such as the habit that has now been created of paying per diems, and the concomitant expectations that have been created. Other contextual factors include poverty, salaries that might need to be topped up (although it is important to compare such salaries with those of others in equivalent positions in different professional fields), and salaries being paid late or not being paid at all, which creates problems with cash flow.

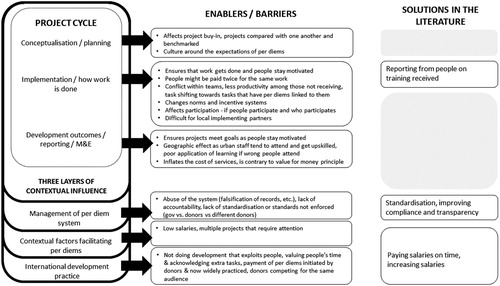

Per diems are clearly not just either barriers or enablers but both, and can have an impact on different dimensions of the project cycle. The data and literature combined suggest that per diems can act as barrier and enabler at various stages of a project. This way of looking at the effects of per diems, and illustrating the extent of their effects, is currently absent from the literature. The influence of per diems, either as barriers or enablers, at different points in the lifecycle of a development project is illustrated in which draws on the previous two sections of this paper on how per diems act as barriers and enablers. Here it can be seen that per diems are relevant at project conceptualisation and design as they influence buy-in into projects – projects are compared, and there is a ‘cultural expectation’ of payment of per diems. When designing a project, or considering work in a particular country context it is important to be aware of how per diems are perceived and what local expectations are. How these expectations will be negotiated, especially if different from what funders allow, needs to be carefully considered upfront as it is likely to influence project implementation at a later stage. Per diems also have a strong enabling or barring influence at the implementation stage of a project where they could act as a motivating factor and incentive to get work done, but could also be an extrinsic incentive that makes it difficult to establish people’s ‘real’ motivations. In order to address the potential misuse of per diems a suggestion for project implementers could be to resist pressure to pay inflated rates, although this does come with the risk of reduced programme participation if per diems act as an extrinsic incentive. However, it might also lead to participation by those who show most interest in the work, as opposed to those who most need additional income. Per diems also play a role in the final delivery of services or project outcomes, for example paying per diems could skew capacity in certain geographic areas as people from more urban areas make use of training opportunities, there can be poor application of learning if the wrong people attend workshops, and per diems inflate project costs and go contrary to the idea of value-for-money in development. International donor agencies have an important role to play in setting standards together with governments on the rates of per diems to be paid, enforcing this, and coordinating efforts with other donor agencies.

The literature and interview data also illustrate that the project cycle and the ways in which per diems influence the different dimensions are situated within three layers of broader contextual influences. The first layer is the management of the per diem system, which includes aspects such as standardisation (the lack or inconsistent application thereof). The second layer includes the various contextual factors that facilitate the existence of per diems, such as poverty, low salaries and multiple development projects in which people participate. The final layer is the larger context of international development practice in which all of these development activities and the practice of paying per diems are taking place. This layer includes aspects such as a system introduced by donors that is now widely practiced and demanded, and donors competing against one another for the same audience while trying to practice development in a way that does not exploit people ().

As illustrated in the diagram, in the literature, as well as in the interview data, when people speak about solutions to some of the barriers caused by the payment of per diems, or alternatives to per diems, the majority of suggestions revolve around better or different management of the per diem system, for example standardising rates across organisations and better enforcement of these standards; involving a wide range of stakeholders in discussions about how per diems should be regulated; and improving the monitoring, control, transparency of and compliance with the per diem system (Aiga, Citation2012; Vian & Sabin, Citation2012; Vian et al., Citation2013). Others focus on trying to address the contextual factors that facilitate the payment of per diems by increasing salaries and paying salaries on time, doing away with discretionary allowances (adding a pre-determined amount to salaries instead); and striving for comparable salaries irrespective of whether an individual works for a local NGO or an international donor agency (Conteh & Kingori, Citation2010; Vian & Sabin, Citation2012; Vian et al., Citation2013).

Using as a reference point, there appear to be many questions surrounding per diems that still require an answer, for example: With such a focus on improving the management of the per diem system, are there best practices or examples that we could learn from where the payment of per diems is working well? If the payment of per diems is a system that is here to stay (to some extent), what efforts are there at an international level between donor agencies to address these issues and/or standardise the practice? How are development efforts addressing the contextual factors such as poverty and low salaries that feed into the facilitation of this system of paying per diems? If a contributing factor is that donors are vying for the same audiences, how can in-country efforts be better coordinated to reduce this competition? What are the costs and benefits from a development ethics perspective of continuing with the practice of paying per diems? These are some of the questions that still require answers when debating the payment of per diems as a barrier to or enabler of international development projects in Africa.

7. Conclusion

This paper has explored how the payment of per diems can act as enabler and barrier in international development projects, drawing on existing literature, experience of programme implementation in Malawi, and interviews with others working in the development sector (civil servants, donors, local and international NGOs). It has illustrated the complexities surrounding this topic, as well as its pervasiveness in the effect that it has on different aspects of the project cycle – something that the literature to date has not illustrated. The paper has taken the discussion beyond the health sector, which is the focus of much of the existing literature, and into the development field more broadly. We hope that this is part of a wider and open discussion on per diems and concur that a large-scale survey is needed to fully understand the nature and extent of the payments of per diems internationally (Aiga, Citation2012).

Acknowledgement

The project on which this paper draws was funded by UK Aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies (grant PO 6123).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 In Malawi we implemented the project through a local NGO as we are not based in country.

References

- Aiga, H, 2012. Train to retain or drain? The need for a global survey for sitting allowances. Public Health 126, 620–3. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.02.009

- Boyatzis, RE, 1995. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Bryce, J, Cutts, F, Naimoli JF & Beesley, M, 1993. What have teachers learnt? The Lancet 342, 160–1. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91352-M

- Chêne, M, 2009. Low salaries, the culture of per diems and corruption, U4 Expert answer http://www.u4.no/helpdesk/helpdesk/query.cfm?id=220 Accessed 14 October 2016

- Conteh, L & Kingori, P, 2010. Per diems in Africa: A counter-argument. Tropical Medicine and International Health 15(12), 1553–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02644.x

- Hanson, S, 2012. Need to reform the remuneration system to initiate a system approach to the health sector in resource-poor countries. Tropical Medicine and International Health 17(6), 792–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02979.x

- Grepin, K, 2009. The per diem culture. The Global Health Blog. http://karengrepin.blogspot.com/2009/07/per-diem-culture.html Accessed 16 October 2016

- Jack, A, 2009. Expenses culture has high cost for world’s poorest nations. Financial Times. www.ft.com/cms/s/0/832f89ea-7c4f-11de-a7bf00144feabdc0.html?nclick_check=1 Accessed 15 September 2016

- Mukuka, C, 2004. Integrated management of childhood Illness in Zambia: A report on the documentation of the IMCI experience, progress, and lessons learned. WHO Regional Office for Africa. http://www.afro.who.int/whd2005/imci/zambia.pdf Accessed 11 August 2016

- Nkamleu, GB & Kamgnia, BD, 2014. Uses and abuses of per-diems in Africa: A political economy of travel allowances. African Development Bank Group, Working Paper Series, no 196, February 2014.

- Ridde, V, 2010. Per diems undermine health interventions, systems and research in Africa: Burying our heads in the sand. Editorial. Tropical Medicine and International Health 15(7), E1–4. doi: 10.1111/tmi.2607

- Roenen, C, Ferrinho, P, & Van Dormael, M, 1997. How African doctors make ends meet: An exploration. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2, 127–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-240.x

- Scotland Malawi Partnership, 2014. Practical guidance and support on per diems. http://www.scotland-malawipartnetship.org/resources/?type=298 Accessed 14 October 2016

- Søreide, T, Tostensen, A, & Skage, A, 2012. Hunting for per diem: The uses and abuses of travel compensation in three developing countries, Norad Evaluation Department, Report 2.

- Therkildsen, O, & Tidemand, P, 2008. Staff management and organisational performance in Tanzania and Uganda: Public service perspectives. Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen.

- Vian, T, 2009. Benefits and drawbacks of per diems do allowances distort good governance in the health sector? U4 Brief No. 29. CMI, U4 AntiCorruption Resource Centre, Bergen, Norway. http://www.U4.no Accessed 14 October 2016

- Vian, T, & Sabin, L, 2012. Per diem policy analysis toolkit U4 Brief No. 8. CMI, U4 AntiCorruption Resource Centre, Bergen, Norway. http://www.U4.no Accessed 14 October 2016.

- Vian, T, Miller, C, Themba, Z. & Bukuluki, P, 2013. Perceptions of per diems in the health sector: Evidence and implications. Health Policy and Planning 28, 237–46. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs056