ABSTRACT

In the past two decades, southern African countries have experienced rapid growth and spread of supermarket chains. This paper assesses the internationalisation of supermarkets and potential reasons for the uneven outcomes seen in different countries in the region. Several factors account for the spread, including rising urbanisation, increasing per capita income, greater economies of scale and scope, and more efficient procurement and distribution systems. However, the current literature does not adequately consider the importance of culture, proximity to suppliers and impact of policy objectives of national governments on the success of supermarkets in host countries, especially in developing countries. It also does not consider the nature of competitive rivalry between supermarkets and how this affects internationalisation. This paper highlights the importance of these factors in understanding the outcomes in selected southern African countries.

1. Introduction

The past two decades have seen the beginning of the fourth wave of the global ‘supermarket revolution’ occurring mainly in eastern and southern African countries (Reardon et al., Citation2004; Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006). The spread of supermarkets in Africa has, until recently, been through foreign direct investment (FDI) emerging from larger African economies.

The internationalisation of supermarkets has important consequences for consumers and suppliers. Supermarkets offer consumers a one-stop shopping experience, a wide range of products and an overall shopping experience that is a package of more than just physical products. This can result in lower overall costs for consumers. From a supplier’s view, supermarkets are an important route to market providing opportunities for participation in value chains which, in turn, can allow for capabilities development (Boselie et al., Citation2003).

Effective competition between supermarket chains benefits consumers through lower prices, increased convenience, improved quality and choice. For suppliers, it leads to more alternatives for the sale of their products and limits potential abuses of buyer power. Concerns have emerged around the anti-competitive conduct of dominant supermarket chains worldwide. In southern Africa, these include the exertion of buyer power over suppliers and conduct that results in rivals being prevented from locating in shopping centres. Such strategic behaviour affects the course, pace and success of internationalisation.

The political, social, cultural and economic realities in each country and the objectives of governments further affect internationalisation. The choice to invest, mode of investment, degree of expansion and procurement practices of supermarkets in host countries are influenced by policies in each country, which vary across the region.

The current literature does not adequately consider the impact of these factors on the internationalisation of supermarkets and is more focused on the internationalisation of manufacturing firms. It does not sufficiently explain how these and other factors result in supermarket chains succeeding in some countries in the region but failing in others, or why different strategies are employed by the same chain in different countries. It also does not provide an understanding of advantages that regional chains may have over global chains. This paper aims to contribute to the literature in these aspects.

Section 2 provides a literature review on supermarket internationalisation globally and the theories behind the rationale for internationalisation. To appreciate the differences between internationalisation in manufacturing and retail, the literature on the unique characteristics of supermarkets and the nature of competitive rivalry is reviewed. Section 3 evaluates the trends in supermarket internationalisation in selected southern African countries and their uneven outcomes, providing explanations of why this may be so. In Section 4, the impact of competitive dynamics between supermarkets on internationalisation and the types of anticompetitive conduct concerns that have arisen in the region are explored. Section 5 concludes.

2. The internationalisation of supermarkets and the nature of competitive rivalry – literature review

The first wave in the global supermarket ‘revolution’ occurred in more affluent South American countries (Brazil, Argentina and Chile), northern central Europe and East Asia (excluding Japan and China) in the 1990s while the second covered Mexico, Central America, South Africa (SA), Southeast Asia and south-central Europe. The third wave hit India, China, poorer Latin and Central America, and Eastern Europe in the 1990/2000s. The most recently documented fourth wave involved eastern and southern Africa, and other South Asian countries (Reardon & Weatherspoon, Citation2003; Reardon et al., Citation2004; Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006).

The first African countries to experience growth of supermarkets were SA and Kenya, followed by a ‘second round’ in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Namibia, Botswana, Swaziland, Mauritius, Mozambique, Angola and then Uganda and Tanzania. West African countries (Ghana and Nigeria) are also seeing supermarket growth, although independent retailers and wet markets still dominate.

The revolution has not only been in terms of spreading across countries, but also within countries from cities to towns to rural areas, spanning a full range of income groups. This has displaced independent retailers and traditional markets. There has however been some resilience by independent retailers in Zambia and SA (Abrahams, Citation2009; das Nair & Chisoro, Citation2015). In SA, around 30–40% of the grocery retail market is served mainly by foreign-owned independent retailersFootnote2 who access their products through buying groupsFootnote3 or wholesalers (Appendix 1). These retailers have in recent years been spurred by income from rising social grants and are frequented by hawkers and customers in township, peri-urban and rural areas.

Countries in the second round of growth of supermarkets in Africa are largely recipients of FDI from SA. Reardon & Weatherspoon (Citation2003) noted that the trend of FDI by global multinational enterprises (MNEs) such as Ahold, Walmart and Carrefour that hit Latin America had at the time not yet hit Africa, although they predicted that this was likely to happen by around 2008. Their predictions were partly accurate, with America’s Walmart entering Africa through a merger with SA’s Massmart, UK’s Poundstretcher entering Zambia and France’s Carrefour entering Kenya, albeit all later than 2008.

While orthodox FDI theories, particularly those linked to trade (Helpman, Citation1984 ), have limiting assumptions such as perfect competition, industrial organisation (IO) based theories accept that there are market imperfections and barriers to entry. Their premise is that FDI happens because firms have specific advantages that make it profitable to invest abroad in production instead of exporting. These advantages are sources of market power and can include possession of patent-protected technology, brand names, business techniques, skilled personnel, marketing and management skills, and cheaper sources of finance (Kindleberger, Citation1969).

The IO-based theories have been extended to view FDI as a way of defending and reinforcing market power in oligopolistic industries, which the literature suggests the nature of competition between large supermarket chains is tending towards (see below). One set of theories is broadly categorised as ‘asset exploiting’ motivations, where investments aim to generate economic rent by using existing firm-specific assets (Dunning, Citation1993; Narula & Dunning, Citation2000). Asset exploiting investments include new market seeking investments – where home markets are saturated and growth prospects exist outside; and efficiency seeking investments – to take advantage of scale and scope economies, differences in consumer tastes and supplier capabilities. Both have potential to explain supermarket internationalisation in southern Africa. Another set of FDI theories is ‘asset augmenting’ where investments seek new strategic assets to protect or enhance existing assets. This is a strategic position on FDI in which decisions of where, when or how to invest are influenced by the actual or expected actions of competitors. Along these lines, a motivation for choosing a location was put forward by Knickerbocker (Citation1973) suggesting that firms in oligopolistic markets follow each other’s location decisions if they are uncertain about production costs in the host country, and therefore, by following their rivals through ‘defensive investments’, they reduce risks. It has been shown that firms which compete in domestic markets tend to follow each other to the same foreign markets, while non-competing firms try to avoid each other geographically when internationalising (Hansen & Hoenen, Citation2016).

While IO-based theories offer motivations for supermarket internationalisation, they alone do not provide sufficient insight on the choice of location or the advantages of ownership. A framework that better contributes to understanding this is Dunning’s Ownership, Location, Internalisation (‘OLI’) framework (Dunning, Citation1977). This framework combines imperfect market-based and internalisation theories, and adds a third important dimension – location. It attempts to explain why and how a firm invests abroad, who produces what goods or services and in which locations.

Ownership advantages explain why some firms invest abroad based on firm-specific advantages (preferential access to markets, control over inputs, patents, managerial structures, marketing skills, access to technology and finance, and scale economies) which allow them to be competitive despite additional costs. Location advantages seek to understand where MNEs choose to locate, depending on transport costs, local market potential, legal, political and institutional frameworks etc. Internalisation refers to the firm’s decision to set up foreign plants to internalise these advantages, rather than to transfer them to foreign firms. Dunning’s OLI ‘eclectic’ approach has been criticised as lacking a robust theoretical foundation, merely combining elements from other theories. Many criticisms were subsequently addressed as the literature developed (Dunning, Citation2001, Citation2006). The eclectic paradigm is nonetheless flexible in that it caters for contextual responses of firms to economic and political features of host economies, as well as industry dynamics, characteristics and objectives of firms. This flexibility is useful for assessing supermarket internationalisation.

However, while having some explanatory potential, the above theories fall short of adequately explaining supermarket internationalisation. The empirical literature is particularly scarce on developing countries, especially in Africa, in which market and consumer dynamics are different from developed countries. As mentioned, existing theories and empirical evidence are mainly focused on manufacturing firms. There has been limited research on the internationalisation of retailers (Coe & Hess, Citation2005). The nature of retail offerings is very different from manufacturing. Given these unique characteristics, trying to explain retail internationalisation using theories and empirical evidence from manufacturing firms is limiting (Alexander & Doherty, Citation2000; Burt et al, Citation2002; Dawson, Citation2007).

A supermarket offering today is much more than a ‘basket of goods’ at a specific price. Supermarkets offer consumers a wide selection of products under one roof; they are convenient, easily accessible, open for long hours and offer a range of other services. Modern retailers are thus said to offer a ‘Price-Quality-Range-Service’ (PQRS) package (Dobson, Citation2015). This can reduce overall costs for consumers, including transport, time, search, information and storage costs. The offering includes an ‘overall customer experience’ (Betancourt, Citation2006; Basker & Noel, Citation2013). In providing these offerings, modern retailers differentiate themselves through store formats (González-Benito et al., Citation2005) such as supermarkets, hypermarkets, convenience stores, discount stores etc.

From an IO perspective, supermarkets have been characterised as natural oligopolies, where a few powerful chains offer quality products and low prices (Ellickson, Citation2013). This stems from Sutton’s (Citation1991) endogenous sunk cost model of competition where market structure is determined by competition to provide higher quality and wider service offerings. As the market grows, existing firms expand sunk cost investments to remain competitive. Such investments limit the number of firms that can profitably enter even large or fast-growing markets. A small but vibrant set of fringe players can grow alongside large supermarket chains, but these do not compete on PQRS in the same way that large chains do, and can grow without large sunk investments (Ellickson, Citation2013). This ties in with the observation in SA of a few large supermarket chains collectively dominating markets, with limited competition from a fringe of independent retailers.

Modern supermarket chains invest heavily in infrastructure, including in supply chains, centralised distribution centres (DCs), IT systems and transport fleets, to get products on shelves at the lowest possible costs (Harvey, Citation2000). Supermarkets in southern Africa are moving towards DCs instead of store-to-store procurement as they modernise (Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006). While offering cost saving benefits, including scale and scope economies, investing in DCs also raises barriers to entry (Basker & Noel, Citation2013). Given high entry barriers and sunk costs, supermarkets can be characterised as having become increasingly oligopolistic over time where there are a few large, powerful chains which tend to have both significant market power (oligopoly) and buyer power (oligopsony), with a consequent high degree of control over entire value chains (Dobson, Citation2015).

Competition within same format supermarkets (‘intra-format’) depends on the closeness of competition between offerings of supermarkets in a shopper’s catchment area; and how prepared consumers are to substitute between offerings. The competitive reaction to lost market share between same format stores can be through price discounting and promotional activity (Ellickson & Misra, Citation2008; Dobson, Citation2015). Competitive pressure can also come from different formats. In Germany, competition to supermarkets comes from other formats like ‘hard-discount’ chain stores Aldi and Lidl (‘inter-format’) even though the offerings of these discounters are very different from what traditional supermarkets offer, stocking narrower ranges of products and providing limited customer service (Verboven et al., Citation2010; Ellickson et al., Citation2016).

Another distinguishing characteristic of supermarkets is location. Consumers tend to shop regularly from supermarkets near their homes or workplaces, creating competition between supermarkets at a very local level.Footnote4 Supermarkets therefore compete for space near residences, central business districts, workplaces or dense housing areas (like township areas in SA). For chains that operate nationally, strategic decisions are often determined at head office and rolled out to stores. These decisions are made based on, amongst other things, overall competitive rivalry between chains and not necessarily rivalry in a specific location. In this sense, the market may be wider than local from an antitrust perspective.Footnote5 In practice however, from a consumer perspective, catchment areas for various formats of grocery retail have been defined as local in several jurisdictions (Dobson, Citation2015).

Given these unique characteristics, retailer and manufacturer internationalisation and competition dynamics are different. Retailers are driven to increase sales, while manufacturers are often driven by cost reduction considerations. Retailer internationalisation further involves a process for the diffusion of managerial knowledge through economic and social systems. This ‘process view’ is supported by the fact that internationalisation affects all levels of consumer goods value chains – from sourcing, logistics and operations to property management and customer relationships (Dawson & Mukoyama, Citation2006).

As highlighted, supermarkets are ‘local’ from the customer’s point of view, irrespective of whether they are part of large multinationals. This requires understanding and adapting to, or even creating, local cultures and following patterns of consumption in host countries. This is not the case for manufacturers. There is no requirement for customers to be in the locality of manufacture and internationalisation is often focused on production for exports (Dawson, Citation2007). Supermarkets can transfer their own culture to host countries to varying degrees. Full internalisation may be central to the development of the firm and part of their core strategy (e.g. Carrefour and Tesco). For these firms, while domestic operations are still important, they almost fully transfer their culture and business models to foreign markets. In contrast, Marks and Spencer’s strategy is not to transfer its culture to foreign markets. With full culture transfer, the influence of senior management is significant, and internationalisation fully transfers strategy, business models, corporate values and operations to host countries (Burt et al., Citation2002; Dawson, Citation2007). The adaptation in host countries may be small if cultures are similar, which might be the case for immediate cross-border internationalisation, or large when trying to succeed in very different markets. There is less of a requirement, if any, for manufacturers to adapt to local cultures. Poor adaptation to local cultures may explain why South African retailers have been less successful in East Africa relative to southern Africa generally. The cultural hurdle may be more easily overcome in markets closer to home, in addition to supply chains being shorter. The degree of adaptation and transfer of culture hinges on managerial ability to adapt to the host market (Wrigley & Currah, Citation2003; Dawson, Citation2007).

The relationships with suppliers and customers are also different for retailers and manufacturers. Retailers have an intimate relationship with suppliers to ensure efficiencies and on-time deliveries, along with constant monitoring of sales. These ‘network’ efficiencies are integral to retailer operations. In manufacturing on the other hand, ‘operational’ efficiencies are often more important, emphasising cost reduction objectives. The different approaches are also seen in the management of suppliers. In retail, the interactions with central head office are important for corporate stores, while for manufacturing, control is usually at local management levels. The portfolio of suppliers is often larger for retailers than manufacturers, and there is a variety of relationships with different suppliers (Dawson, Citation2007).

3. The internationalisation of supermarkets in southern Africa

The internationalisation of supermarkets in Africa has until recently been dominated by South African chains – Shoprite Holdings, Pick n Pay Stores, the SPAR Group, Woolworths Holdings, and Fruit and Veg City (Food Lovers Market). However, the last decade has seen the spread in southern (and East) Africa of other African chains such as Botswana-owned Choppies Enterprises, and entry by international chains like Walmart, Carrefour and Poundstretcher.

Demand-side factors spurring internationalisation include rising urbanisation, growing income and increased demand for convenience as the middle class grows (Reardon et al., Citation2004; Tschirley, Citation2010). From the supply side, a major driving force has been increased FDI given saturation of home markets and greater sales and profitability opportunities in developing countries (Humphrey, Citation2007).Footnote6 This has been fuelled by retail and trade liberalisation, including as part of structural reform programmes in the 1990s in many African countries. Economies of scale and scope, and the modernisation of procurement, inventory management and logistics systems have further spurred growth.

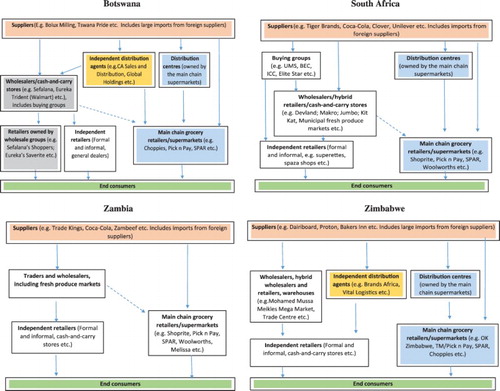

shows the main supermarket chains in Botswana, SA, Zambia and Zimbabwe, and their ownership and market shares based on store numbers.Footnote7 A few large chains dominate in each country. Favourable trade conditions through Southern African Development Community (SADC) trade agreements (with preferential/no import duties on certain products) and proximity to SA make it easier for South African supermarkets to operate in the region relative to global chains, given that their supplier base is concentrated in SA. A large proportion of imports on supermarket shelves in SADC are indeed from SA.Footnote8 This highlights important regional dimensions which support a ‘regional’ value chain approach in understanding certain supply chains in southern Africa.

Table 1. Number of supermarkets, ownership and % share in each country (formal chain stores only), 2016.

South African chains hold a significant portion of the national market in Zambia (55%), Botswana (37%) and Zimbabwe (33%) (), although the proportions vary in the countries reflecting the different degrees of success of the chains. Shoprite was the first to internationalise. Headquartered in SA, it operates in 14 other African countries. In SA, Shoprite has a range of different formats catering for all income groups, as well as fast food, furniture, liquor and pharmacy outlets. Shoprite has a lower-income segment offering through ‘Usave’ and competes at the higher end through ‘Checkers’. Listed on the Johannesburg (JSE), Namibian and Lusaka stock exchanges, Shoprite is the only South African chain to have multiple listings on the continent.Footnote9

The reasons for supermarkets investing in Zambia are straightforward. Zambia has been one of the fastest growing countries in SADC, with an average gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of around 7% () and an increase in the proportion of urban population of 18% between 2000 and 2015 (). This is higher than the overall continent increase of 17% and higher than the other countries studied. Although past research has shown that supermarkets accounted for a small proportion of food sold in Zambia (Abrahams, Citation2009), the growth of South African and multinational chains in the past seven years suggests that this proportion is growing. These factors contribute to the strong presence of South African supermarkets in Zambia investing to access the growing urban population with rising disposable income (); this is in line with new market seeking theories of FDI.

Figure 1. Proportion of urban population, 2000–15. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2014). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision.

Table 2. GDP growth rates, 2000–15.

In Zambia, Shoprite had the first-mover advantage when it bought former state-owned supermarkets during the privatisation phase in the 1990s. Essentially ‘taking over’ the local competition, Shoprite grew initially via acquisitions and then organically (Reardon & Weatherspoon, Citation2003), bolstered by government support (including tax rebates and import tariff concessions). While there is some competition from traditional markets and independent retailers, these are not direct rivals in terms of the full PQRS offering that urban consumers are gravitating to.

Botswana has seen GDP growth rates and per capita levels close to SA’s (although urban population increases are lower) (). It is also closer to SA than Zambia is. Yet, South African chains have not gained as much share as they have in Zambia. This is partly attributable to strong local competition. The growing retail culture in Botswana has been largely captured by local chain, Choppies (discussed below). South African chains also face competition from vertically integrated wholesalers and retailers with similar offerings (e.g. Sefalana, see Appendix 1). The licensing of traders of goods regulated by the Trade Act of 2003 and the Trade Act Order of 2008 prevents wholesalers from selling directly to end-consumers. To remain competitive in the face of expanding supermarkets, wholesalers have vertically integrated into retail. Multinational supermarkets therefore compete not only with Choppies, but also with vertically integrated wholesalers and retailers.

Similarly, in Zimbabwe, South African supermarkets have grown slowly. Given the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment requirements of 2011 which stipulate that 51% of shareholding should be owned by Zimbabweans, Pick n Pay operates as a joint venture with local chain, TM Supermarkets. Local chain OK Zimbabwe and TM/Pick n Pay collectively hold over half the market. Additional factors such as unfavourable economic conditions, protectionist policies and trade restrictions on imports further make it difficult for multinationals given limited local supplier capacity.

Shoprite’s performance outside SA shows that new market seeking theories are relevant in explaining its internationalisation. Profit and sales growth outside SA are rising (). Compound annual growth rates (CAGR) of sales between 2010 and 2016 for non-SA operations were around 21% compared to around 10% for SA, and CAGR of profits were higher for non-SA operations (17%) than SA operations (13%).

Pick n Pay is the second largest retailer in SA specialising in groceries, clothing and general merchandise. In SA, Pick n Pay operates across multiple store formats, both franchised and corporate-owned, and has liquor, clothing and fuel court convenience outlets. Pick n Pay also started targeting lower-income consumers through the acquisition of Boxer Superstores. However, compared to Shoprite, Pick n Pay’s performance has been weaker and it has internationalised to a lesser degree ( and ).

Figure 3. Shoprite and Pick n Pay’s SA and non-SA supermarket sales and profits, 2010–16. Source: Shoprite and Pick n Pay Annual Reports.

Note: The sales figures represented by bars are on the primary (left) axis, while the profit figures represented by lines are on the secondary (right) axis.

Pick n Pay’s relative lack of success in the region can be traced back to floundering profitability at home until 2013 (). Twenty years ago, its market value exceeded Shoprite’s in SA. Today, its value is only around a third of Shoprite’s. Pick n Pay faced significant growth challenges given lack of adaptation to the changing South African market and emerging black middle class,Footnote10 and slow pace of retail modernisation including in DC investments.

Shoprite is over 85% centralised. Its sophisticated distribution infrastructure is credited for achieving world-class trading margins and low prices. Pick n Pay invested over ZAR 2 billion in its DCs collectively in the past decade to catch up to the rest of the industry, particularly Shoprite. Its new management implemented other turn-around strategies, which appear to have borne fruit in recent years. From 2013, sales and profits in Africa started seeing growth although off a much smaller base than Shoprite (). Pick n Pay now recognises African markets as its second engine of growth, generating revenue of over ZAR billion in 2016. CAGR of profits between 2012 and 2016 for the rest of Africa were 46% compared to around 3% in SA, while CAGR of sales in the rest of Africa were almost 20% compared to only 7% in SA. Pick n Pay is only listed on the JSE.

3.1. Why has Shoprite been so successful in the region?

Shoprite has undoubtedly been the market leader in terms of keeping up with evolving markets, investing in modernisation and exploiting opportunities in the region. It has achieved this through ownership advantages, including size, dynamic management, efficient DCs, organisation innovation, respected brand name and access to capital. These advantages reduce costs, which is important for consumers in the region as part of the PQRS package. Pick n Pay on the other hand has played the follower role to remain competitive.

Another aspect that Shoprite got right was building relationships with local suppliers. Its fresh produce procurement arm, Freshmark, has increased sourcing of fruit and vegetables from within host countries in the region. While previously most fresh produce for stores in Zambia was imported from SA, now only fruit is imported while vegetables are largely sourced locally. Freshmark has been able to identify suitable local farmers in Zambia (Reardon & Weatherspoon, Citation2003; Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009; Ziba & Phiri, Citation2017). Shoprite has also entered an agreement with a large beef producer in Zambia, Zambeef, to run 20 in-store butcheries. Recently, Shoprite undertook to support small enterprises through agreements with the Zambia Development Agency, the Ministry of Trade, Commerce and Industry, and the Private Enterprise Programme under the Department for International Development programme. The other South African supermarkets have only more recently seriously started their expansion into Africa, and while they too are starting to build relationships with suppliers, Shoprite has had the first-mover advantage in countries with limited supplier capacity. There are still serious concerns however that local supplier inclusion is not at the level it should be.

Listed on the JSE, the SPAR Group (SA) is the third largest grocery retailer in SA operating through a franchise model. However, SPAR in Zambia is not part of the SA group, but part of SPAR International in the Netherlands, operating as a joint venture (JV) between Innscor International, Zimbabwe and Platinum Gold Zambia. Sanctions in SA during the 1950s also forced the SPAR group in Zimbabwe to seek their own rights directly from SPAR International (). The South African SPAR Group is however present in Botswana, Swaziland, Namibia and Mozambique. The franchise business model of SPAR where individual owners’ own stores, on one hand, could promote its internationalisation. The benefits of franchises, including ease of making decisions at store level, greater latitude for local procurement, increased levels of personalised service to consumers and access to group DCs, may make it easier, and less risky, to internationalise through franchises. On the other hand, different owners can result in different qualities and inconsistencies across stores, which may negatively affect the brand name.

Woolworths Holdings, listed on the JSE, is the fourth largest retail chain in SA, specialising in food and clothing. Unlike the other chains, the group’s food stores exclusively target high-income consumers. Its presence in the other countries is limited, starting off with clothing and gradually diversifying into grocery retail. This is partly due to Woolworths’ target market being upper-income consumers and partly due to its procurement model. Unlike the other chains, majority of Woolworths’ products are house brands/private labels, with Woolworths forming close relationships with SA suppliers who custom-manufacture exclusively for them. There is a lack of supplier capabilities in the region to produce the quality required, making Woolworths dependent on imports.

The fifth largest grocery retailer in SA is Fruit and Veg City Holdings (FVC). It expanded rapidly since its first store opening in 1993 and now has over 100 stores throughout southern Africa. Like the other supermarkets, it has evolved to targeting customers across income groups, including through its up-market Food Lover’s Market format. FVC is not listed. In 2007, Pick n Pay sought to merge with it but the transaction was prohibited on grounds that it would remove an effective competitor. The Competition Commission of South Africa (CCSA) found that FVC was a growing competitor to Pick n Pay and would be an even stronger competitor in the future. FVC’s turnover indeed more than tripled between 2006 and 2015, with a growth rate well ahead of the major listed food retailers (das Nair & Chisoro, Citation2015).

Unlike the other chains, FVC’s model is predominantly the sale of fresh fruit and vegetables, with a small but growing proportion of other groceries. FVC primarily procures fresh produce daily from municipal produce markets and not directly from farmers. This has allowed it to offer cheaper prices for fresh produce, and has also provided a source of demand for farmers not able to deal directly with the large chains. FVC has recently ventured into the region and faces competition from other supermarkets and wet markets. As FVC grows in the region, it is likely to develop stronger links with fresh produce markets and farmers, although at present much of its produce is imported.

Recently, Walmart-owned Game branched into food products (Foodco). It also targets low-income consumers through Cambridge Foods, and offers hybrid wholesale and retail sales through Makro. While Game has the advantage of Walmart’s immense global supplier base, allowing it to benefit from lower costs, it has yet to gain traction in southern Africa as a grocery retailer. This raises the question of why a large multinational with significant ownership advantages and access to global supply networks has seen slow growth in southern Africa. Advantages that could translate into lower prices for consumers are alone apparently not sufficient for success. This highlights the importance of supplier relationships and the ability to respond to consumer cultures in host countries. Location advantages of regional chains in terms of access to well-trusted suppliers from their home country with whom they have strong relationships have a bearing in this regard. Shorter supply chains and lead times may be more beneficial than having numerous deep-sea suppliers, especially for perishable products. Being relatively new in the grocery retail space, Game has to build these relationships. Walmart has however also openly conceded to a slower, more cautious approach in expanding into Africa given certain risks.Footnote11

The ability to adapt to host country culture may be easier for regional supermarkets than for global MNEs like Walmart. Shoprite has been able to do this more successfully than even the other South African supermarkets. This may be due to its first-mover advantage and managerial responsiveness, which has allowed it to build a brand that consumers trust. The success of regional supermarkets over global MNEs is further seen in the recent entry and growth of Choppies. Choppies has over the last decade grown from two stores in home Botswana to over 190 stores in the region. Recently, it also entered Kenya. The fast-growing African market is a key motivation for Choppies’ expansion into Africa, again supporting new market seeking theories of internationalisation. Choppies’ target market is low-to-middle-income consumers, but it is also attempting to attract middle-to-upper-income consumers. Listed on both the Botswana and Johannesburg stock exchanges, Choppies is the only supermarket other than Shoprite to have more than one listing in Africa.

Choppies imports significantly from SA and from global sources because of Botswana’s limited manufacturing capacity. Yet, Choppies’ growth rate (in store numbers) has been higher than both Walmart and South African chains. This can be attributed to its aggressive growth strategy mainly via acquisitions of existing, already established supermarkets strategically located along key transport routes and urban locations. Choppies has also invested in DCs. Its stores are typically open for longer hours and stock a wide range of lower-priced, private label products. This highlights the importance of adapting to consumer preferences and culture in host countries.

The political, social and economic policy objectives in each country also have an impact on supermarket internationalisation. For instance, laws that prevent wholesalers from offering retail sales in Botswana, as noted have resulted in wholesalers vertically integrating with retail outlets, an outcome that is unique to Botswana. The indigenisation laws in Zimbabwe have seen MNEs enter through non-controlling JVs with local supermarket chains, a mode of entry not seen in the other countries. These laws limit the entry of supermarkets in Zimbabwe.Footnote12 In contrast, the approach to retail FDI in Zambia has been liberal, with policies actively encouraging entry and growth of MNEs.

Despite the countries studied being part of SADC, each country pursues its own policies to protect respective national industries and local suppliers. This includes local content requirements (sourcing a minimum proportion of goods locally) and trade restrictions. Protectionist measures are strongest in Zimbabwe with high import duties on a range of products. In Botswana and Zambia there are outright bans on imports of poultry and maize meal, and other non-tariff barriers such as vitamin A fortification for sugar and non-GMO requirements for grain (in Zambia). While SA, Botswana and Zambia have ‘softer’ local content requirements, Zimbabwe’s Competition and Tariff by-laws set a hard threshold that stipulate supermarkets are to procure at least 20% of products locally. This impacts internationalisation.

4. Competition and the impact on internationalisation

Competition affects, and is affected by, the internationalisation of supermarkets. The intensity of competition differs in the countries assessed. As noted, competition between supermarkets (and between supermarkets and other grocery retailers) results in more options for suppliers, improving their chances of obtaining favourable trading terms as they can play alternatives off against each other. Competition also benefits consumers, creating the dynamism that is essential for lower prices, better quality, greater innovation, more convenience and wider ranges.

Chains in SA have diversified their formats to include supermarkets, hypermarkets, convenience stores at fuel forecourts, liquor outlets, fast food offerings etc. All the chains, except Woolworths, have offerings to target customers of all income levels. Supermarkets thus compete to offer a full suite of formats, where similar formats compete more vigorously (intra-format competition). This is also reflective of the relative maturity of the industry in SA. Multiple formats are not yet offered in the other countries assessed, but as these markets mature, multiple formats will likely evolve. Intra-format competition is especially seen in the offering of lower-priced house brands. There is also a degree of inter-format competition with vertically integrated wholesalers and retailers buying group-led independent retailers and general independent retailers.

Whilst there may be competition between existing supermarket chains, there has been limited entry of new chains with formats competing with the incumbents. The South African supermarket industry remains concentrated with the top four – Shoprite, Pick n Pay, SPAR and Woolworths – collectively dominating markets. It was several years before FVC gained traction to become an effective rival. The other significant new players, Choppies and Game, entered almost two decades after FVC. This is reflective of the high barriers to entry. High levels of concentration are also seen in the other countries ().

The strategic behaviour of incumbents with market power also creates barriers to entry. A historic concern in SA is the practice of supermarkets entering lease agreements with property owners in shopping centres that contain exclusivity clauses. This prevents new retailers and specialist stores like butcheries and bakeries from locating in lucrative spaces, limiting their ability to grow. Physical location and attractive store sites are important if entrants are to become effective competitors. Property developers provide supermarkets with these sites, with the most desirable sites located inside shopping centres where customer traffic is dense. Exclusive leases signed by anchor tenants, which are often supermarkets, grant them rights to operate as the sole supermarket in the mall. From the property owners’ point of view, incumbent supermarkets are ‘must have’ anchor tenants to secure financing from banks, given the high footfall they attract. Although banks may not insist on exclusivity, they require anchor tenants before approving finance to guarantee returns. The typical argument by anchor supermarkets for exclusive leases is that property developers would not construct a mall without their commitment. This highlights their strong bargaining position.

Leases in SA typically last ten years, but anchor tenants have options for renewal resulting in exclusivity spanning several decades. While exclusive leases might arguably be justified in the initial phases of investment to allow anchor supermarkets to recoup investments, gain footfall and establish markets, it is hard to see how they are reasonable for extended periods of time. Small property developers, particularly in rural areas, who do not have bargaining power against major supermarkets, are more inclined to succumb to exclusive leases to kick-start developments. Lack of competition has far-reaching consequences in rural areas where pricing is a key factor for poor consumers and where the nearest alternative supermarket is further away than in urban areas, increasing transport and search costs.

The CCSA has received complaints about exclusive leases over the years (including from FVC and Walmart), and in 2015 announced a grocery retail market inquiry considering this issue amongst others. The inquiry is on-going. Some of the South African supermarkets have attempted to ‘export’ the practice of exclusive leases to the other countries assessed. This affects internationalisation of other chains.Footnote13 Internationally, the UK Competition Commission required phasing out of exclusive leases in its 2010 Groceries Market Investigation Order following recommendations from the former Office of Fair Trading. In Australia, following an inquiry by the competition authority, the major supermarket chains voluntarily provided court-enforceable undertakings which phased out exclusive leases.

Competition between supermarkets can also be dampened when supermarkets exert buyer power to enter exclusive agreements with key suppliers, preventing them from supplying ‘must-have’ products to rival supermarkets or independent retailers. Supermarkets in the region appear to generally not impose exclusivity conditions except in the supply of house brands. Certain suppliers are developed by supermarkets to exclusively supply house brands and are typically not permitted to sell the brand to rivals. However, even if suppliers are free to supply rivals, the various costs imposed on them by large supermarkets may negatively affect the trading terms between these suppliers and rivals as compensation for these higher costs (the ‘waterbed effect’, Inderst & Valletti, Citation2011). In SA, it is often difficult for independent retailers or buying groups to get similar trading terms to the large supermarket chains even for equivalent transactions. The buyer power of supermarkets is explored in das Nair & Chisoro (Citation2016, Citation2017).

5. Conclusion

While South African chains have been the drivers of regional supermarket FDI historically, this is changing with other regional and global MNEs emerging. Internationalisation has been motivated by sales opportunities in the region. Although global chains have entered, their success has been muted, highlighting the advantages that regional chains have over them. Stemming from the unique characteristics of supermarkets, these advantages include strong relationships with, and proximity to, SA suppliers, better awareness of cultures and trends, brand reputation and trust. The degree of internationalisation differs even between SA chains as seen by the experiences of Shoprite and Pick n Pay. Shoprite is clearly dominant in the internationalisation game, potentially explained by, in addition to supplier networks, its first-mover advantage, ownership advantages (dynamic management, market positioning, quicker response to changing markets) and investments in modernisation.

While important, ownership and location advantages alone are not sufficient to understand internationalisation. Political, social and economic policy objectives in each country impact internationalisation. These influence the choice to invest, the mode of investment, the degree of expansion and the procurement practices in host countries. National–local content policies, import duties and quotas that protect local industries, and that are not harmonised across the region, impact internationalisation. Promoting internationalisation requires reducing restrictions to trade and harmonising policies, potentially creating regional content policies for supermarkets.

Finally, with internationalisation of only a handful of large supermarket chains comes the potential for abuses of market power. To ensure effective rivalry, competition authorities (local and regional) can play a key role in reducing certain barriers, for instance, facilitating legally enforceable undertakings by supermarkets to not enter exclusive leases, or to reduce their duration and scope. Municipalities can also actively encourage a diversity of retail formats as part of spatial planning policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This paper draws from research undertaken for UNU-WIDER by das Nair & Chisoro (Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2017), Ziba & Phiri (Citation2017) and Chigumira et al. (Citation2016).

2 Supermarkets, cash-and-carrys, wholesalers with retail offerings (hybrid) as well as informal ‘spaza’ shops.

3 Unitrade Management Services, Buying Exchange Company, Independent Buying Consortium, Independent Cash & Carry Group, Elite Star Trading etc.

4 The UK Competition Commission in its retail market inquiry defined geographic markets as being limited to 5–15 minutes drivetime depending on whether they were large, mid-sized or convenience grocery stores.

5 JD Group Limited/Ellerine Holdings Limited, 78/LM/Jul00.

6 Annual Reports of the listed supermarkets confirm this.

7 Revenue or sales by country for each supermarket is a better measure. This data is however not consistently publicly available for all supermarkets.

8 There is antagonism towards South African supermarkets because of their procurement practices that favour South African imports even when there are local options (Abrahams, Citation2009). See das Nair & Chisoro (Citation2016) on the impact on local suppliers.

9 An indication of the extent of its internationalisation (Dörrenbächer, Citation2000).

10 http://www.financialmail.co.za/coverstory/2016/06/03/can-pick-n-pay-regain-its-former-glory, accessed 1 October 2016.

11 http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/wall-street-journal/walmarts-growslow-with-massmart-in-africa/news-story/8c218d4270ac5c01329e2b87d753d1f5, accessed on 10/03/2017.

12 Although Choppies has not entered Zimbabwe through a JV. The reason for this exception is unclear.

13 The role of South African property developers operating in the region requires further research.

References

- Abrahams, C, 2009. Transforming the region: Supermarkets and the local food economy. African Affairs 109/434, 115–34. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Royal African Society.

- Alexander, N & Doherty, AM, (Eds.), 2000. The internationalization of retailing. International Marketing Review, special issue 17(4/5), 307–475. doi: 10.1108/02651330010339888

- Basker, E & Noel, M, 2013. Competition challenges in the supermarket sector with an application to Latin American markets. Report for the World Bank and the Regional Competition Centre for Latin America. CRCAL, Mexico, DF.

- Betancourt, R, 2006. The economics of retailing and distribution. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Boselie, D, Henson, S & Weatherspoon, D, 2003. Supermarket procurement practices in developing countries: Redefining the roles of the public and private sectors. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85(5), 1155–61. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00522.x

- Burt, S, Mellahi, K, Jackson, TP & Sparks, L, 2002. Retail internationalization and retail failure: Issues for the case of Marks and Spencer. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 12, 191–219. doi: 10.1080/09593960210127727

- Coe, N & Hess, M, 2005. The internationalization of retailing: Implications for supply network restructuring in East Asia and Eastern Europe. Journal of Economic Geography 5, 449–73. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbh068

- Chigumira, G, Chipumho, E, Mudzonga, E & Chiunze, G, 2016. The expansion of regional supermarkets chains, changing models of retailing and the implications for local supplier capabilities in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit (ZEPARU). UNU-WIDER.

- das Nair, R & Chisoro, S, 2015. The expansion of regional supermarket chains: Changing models of retailing and the implications for local supplier capabilities in South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2015/114

- das Nair, R & Chisoro, S, 2016. The expansion of regional supermarket chains and implications for local suppliers: A comparison of findings from South Africa, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2016/169

- das Nair, R & Chisoro, S, 2017. The expansion of regional supermarket chains: Implications on suppliers in Botswana and South Africa. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2017/26

- Dawson, J, 2007. Scoping and conceptualising retailer internationalisation. Journal of Economic Geography 7, 373–97. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbm009

- Dawson, JA & Mukoyama, M, 2006. The increase in international activity by retailers. In Dawson, JA Larke, R & Mukoyama, M (Eds.), Strategic issues in international retailing. Routledge, London, pp. 1–30.

- Dobson, P, 2015. Structural issues in the groceries sector: Merger and regulatory issues. Background paper by the OECD Secretariat – Latin American Competition Forum, Session I – DAF/COMP/LACF (2015)13.

- Dörrenbächer, C, 2000. Measuring corporate internationalisation: A review of measurement concepts and their use. Intereconomics May/June 2000.

- Dunning, JH, 1977. Trade, location and economic activity and the multinational enterprise: A search for an eclectic approach. In Ohlin, B, Hesselborn, P & Wijkman, P (Eds.), The international allocation of economic activity. MacMillan, London, pp. 395–418.

- Dunning, JH, 1993. Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Addison-Wesley, Harlow.

- Dunning, JH, 2001. The eclectic (OLI) paradigm of international production: Past, present and future. International Journal of the Economics of Business 8(2), 173–90. doi: 10.1080/13571510110051441

- Dunning, JH, 2006. Towards a new paradigm of development: Implications for the determinants of international business. Transnational Corporations 15(1), 173–227.

- Ellickson, PB, 2013. Supermarkets as a natural oligopoly. Economic Inquiry 51(2), April 2013, 1142–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2011.00432.x

- Ellickson, PB, Griecob, P & Khvastunovb, O, 2016. Measuring competition in spatial retail: An application to groceries. Draft paper. 3 March 2016.

- Ellickson, PB & Misra, S, 2008. Supermarket pricing strategies. Marketing Science 27(5), 811–28. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1080.0398

- Emongor, R & Kirsten, J, 2009. The impact of South African supermarkets on agricultural development in the SADC: A case study in Zambia, Namibia and Botswana. Agrekon 48(1), (March 2009), 60–84. doi: 10.1080/03031853.2009.9523817

- González-Benito, O, Munoz-Gallego, PA & Kopalle, PK, 2005. Asymmetric competition in retail store formats: Evaluating inter- and intra-format spatial effects. Journal of Retailing 81(1), 59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2005.01.004

- Hansen, M & Hoenen, A, 2016. Global oligopolistic competition and foreign direct investment. Critical Perspectives on International Business 12(4), 369–87. doi: 10.1108/cpoib-03-2014-0017

- Harvey, M, 2000. Innovation and competition in UK supermarkets. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 5(1), 15–21. doi: 10.1108/13598540010294892

- Helpman, E, 1984. A simple theory of international trade with multinational corporations. Journal of Political Economy 92, 451–71. doi: 10.1086/261236

- Humphrey, J, 2007. The supermarket revolution in developing countries: Tidal wave or tough competitive struggle? Journal of Economic Geography 7(4), 433–50. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbm008

- Inderst, R & Valletti, T, 2011. Buyer power and the waterbed effect. The Journal of Industrial Economics 59(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6451.2011.00443.x

- Kindleberger, C, 1969. American business abroad. The International Executive 11, 11–12. doi: 10.1002/tie.5060110207

- Knickerbocker, FT, 1973. Oligopolistic reaction and multinational enterprise. Division of research, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States.

- Narula, R & Dunning, J, 2000. Industrial development, globalisation and multinational enterprises: New realities for developing countries. Oxford Development Studies 28(2), 141–67. doi: 10.1080/713688313

- Reardon, T & Hopkins, R, 2006. The supermarket revolution in developing countries: Policies to address emerging tensions among supermarkets, suppliers, and traditional retailers. The European Journal of Development Research 18(4), 522–45. doi: 10.1080/09578810601070613

- Reardon, T, Timmer, P & Berdegue, J, 2004. The rapid rise of supermarkets in developing countries: Induced organizational, institutional, and technological change in agrifood systems. e-Journal of Agricultural and Development Economics 1(2), 168–83.

- Reardon, T & Weatherspoon, D, 2003. The rise of supermarkets in Africa: Implications for agrifood systems and the rural poor. Development Policy Review 21(3), 333–55. doi: 10.1111/1467-7679.00214

- Sutton, J, 1991. Sunk cost and market structure: Price competition, advertising, and the evolution of concentration. MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Tschirley, D, 2010. Opportunities and constraints to increased fresh produce trade in east and southern Africa. Paper prepared for 4th video conference under AAACP-funded series of high value agriculture seminars.

- Verboven, F., Cleeren, K, Dekimpe, MG & Gielens, K, 2010. Intra- and inter-format competition among discounters and supermarkets. Marketing Science 29(3), 456–473. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1090.0529

- Wrigley, N & Currah, A, 2003. The stresses of retail internationalization: Lessons for Royal Ahold’s experience in Latin America. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 13, 221–43. doi: 10.1080/0959396032000101336

- Ziba, F & Phiri, M, 2017. The expansion of regional supermarket chains: Implications for local suppliers in Zambia. Zambia Institute for Policy Analysis and Research (ZIPAR). UNU-WIDER.