ABSTRACT

This paper estimated the relationship between employment and depression, hypertension, diabetes and tuberculosis in South Africa between 2008 and 2014. South Africa has high levels of economic inactivity and unemployment as well as a high disease burden occasioned by depression, other non-communicable diseases and tuberculosis. Data came from the National Income Dynamics Study panel dataset. Using fixed effects, random effects and pooled ordinary least squares regressions, depression and diabetes were associated with a 4–6 percentage point decline in employment probability, while tuberculosis was associated with a 12–13 percentage point employment decline. The results suggested that the employment-health relationship possibly operated through illness being associated with increased economic inactivity, rather than through making the search efforts of the unemployed unsuccessful. Moreover, the employment-health relationship not only existed contemporaneously, but extended into the future (especially for the physical health indicators).

1. Introduction

Health is intuitively an important determinant of economic performance, and one way through which health may affect the economy is the labour market. Healthy people are more likely to work or seek employment than the sick because they are more capable of working longer, harder, productively and consistently (Jack & Lewis, Citation2009). Thus, the opportunity cost of non-participation in the labour market is generally higher among the healthy, increasing their probability of participation. Similarly, poor health may decrease labour market participation and earnings through reduced investment in human capital accumulation, like education (Jack & Lewis, Citation2009). Moreover, poor health can result in the sick valuing time spent away from labour market activities relatively more highly than the healthy due to, say, such time being used in seeking health care (Chirikos, Citation1993).

Labour market activities can also affect health. For instance, employment-based income can be used to obtain better health care and nutrition (Nwosu & Woolard, Citation2017). Moreover, employment can have beneficial health effects similar to exercise, while employment-related satisfaction may boost psychological health (Nwosu, Citation2015). Unemployment can also have detrimental effects on mental health (Paul & Moser, Citation2009). However, employment under adverse conditions can worsen health (Ross & Murray, Citation2004).

Most developing country evidence on the effect of health on labour market outcomes have generally focused on physical health indicators like height, body mass index, age at menarche and nutrient intake (Savedoff & Schultz, Citation2000; Knaul, Citation2001; Thomas & Frankenberg, Citation2002; Schultz, Citation2002; Habyarimana et al., Citation2005). Developing country studies on mental health and the economy have largely focused on the relationship between mental health and poverty, with virtually no evidence on the possible relationship between mental health and employment (Patel & Kleinman, Citation2003; Das et al., Citation2007). Studies on the joint relationships between physical and mental health on the one hand and employment on the other, in developing countries are generally lacking.

However, both aspects of health are likely important in partly determining labour market performance. For instance, an individual in good physical health may not be an effective job seeker if she suffers from, say, anxiety disorder. Similarly, a mentally sound individual may exit the labour market if she suffers from a major physical impairment.

In this paper, we estimate the relationship between employment on the one hand, and depression (a mental health disorder), hypertension, diabetes and tuberculosis (physical health indicators) on the other, in South Africa over a six-year period. As will be seen in Sections 1.1 and 1.2, these health conditions constitute a significant proportion of the disease burden both globally and in South Africa. Our contributions include the use of a panel dataset to ascertain whether mental and/or physical health indicators have any significant association with employment in South Africa, as well as whether the relationship (if any) differs across gender and age. By estimating a fixed effects model, we account for unobserved heterogeneity (e.g. taste for work and innate ability), which may independently affect one’s attempts/chances at finding a job. Failure to account for such unobserved heterogeneity may bias the estimated relationship between employment and health, given that such unobserved heterogeneity is likely correlated with the health indicators. This was overlooked by previous studies in South Africa due to data constraints (Booysen et al., Citation2004; Levinsohn et al., Citation2013). Moreover, previous studies in South Africa restricted their analyses to the relationship between HIV/AIDS and (un)employment. This paper however, captures the associations between employment and other less-researched but important contributors to the country’s epidemiological profile.

However, as implied in the foregoing, this study does not estimate causal effects of health on employment. This is because, given the afore-mentioned possible bi-directional relationships between employment and health, a causal study will require instrumental variables or other means of isolating the pure effect of health on employment. Unfortunately, we do not have any of these at our disposal. Therefore, this paper is a first step aimed at ascertaining the existence of an association between the aforementioned mental and physical health indicators and employment in South Africa, while controlling for unobserved heterogeneity. Upon the availability of requisite data, a sequel shall ascertain the existence of a causal relationship between these health indicators and employment in the country.

1.1 The global burden of depression, hypertension, diabetes and tuberculosis

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that depression, which is the leading cause of disability globally, affects about 350 million people, while less than half (and in some cases, less than 10%) of sufferers receive treatment (World Health Organisation, Citation2017a). WHO estimates that unipolar depression is twice as prevalent among females as males (World Health Organisation, Citation2017b). Moreover, depression was the third most important contributor to years lived with disability (YLDs) both globally and in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in 2015 (Vos et al., Citation2016).

Complications associated with hypertension result in approximately 9.4 million deaths annually (World Health Organisation, Citation2013), while the global prevalence of raised blood pressure for those aged 18+ years was 22% in 2014 (World Health Organisation, Citation2014a). The rate of high systolic blood pressure (SBP) exceeding 110–115 mm Hg increased from 73 119/100 000 population in 1990 to 81 373/100 000 population in 2015; for SBP > 140 mm Hg, the rate increased from 17 307/100 000 population to 20 526/100 000 population between 2005 and 2015 (Forouzanfar et al., Citation2017).

The global diabetes prevalence increased from 4.7% in 1980 to 8.5% in 2014 for adults aged 18+ years, resulting in an increase in the number of sufferers from 108 million to 422 million over the same period. Diabetes prevalence in the WHO Africa region increased from 3.1% in 1980 to 7.1% in 2014 for this age group, while the number of diabetes sufferers in the region increased from 4 million to 25 million over the same period (World Health Organisation, Citation2016a). Moreover, diabetes was the sixth largest contributor to YLDs globally, and the fifth in SSA in 2015 (Vos et al., Citation2016).

Globally, the tuberculosis (TB) incidence was about 142/100,000 population in 2015. Though the number of TB deaths fell by 22% between 2000 and 2015, it remained one of the top ten causes of mortality worldwide in 2015. A decomposition of the 2015 TB incidence shows that 56% occurred among males, 35% among females, and 10% among children (World Health Organisation, Citation2016b).

1.2 The South African context and employment-health literature

In South Africa, non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which most of the above health conditions are examples of, are an important contributor to the country’s disease burden. NCDs constituted about 43% of mortality in South Africa in 2012 (World Health Organisation, Citation2014b). One category of NCDs which is of significance to South Africa is mental health. According to the South African Depression and Anxiety Group, over 25% of South African workers have been diagnosed with depression by a health care professional (SADAG, Citation2015).

Hypertension has also remained a significant contributor to the national disease burden. At 77.9%, South Africa has one of the highest prevalence rates globally for people aged 50 years and above (Lloyd-Sherlock, Beard et al., Citation2014). However, treatment is highly inadequate, as less than 10% of sufferers in the country had access to effective treatment (Lloyd-Sherlock, Ebrahim et al., Citation2014).

The story is similar regarding TB, with the country having the highest rate of TB globally. In 2015, the rate of TB in the country was 834/100 000 population, while the country was among the six countries accounting for 60% of new TB cases globally in that year (World Health Organisation, Citation2016b). South Africa is also one of four countries accounting for half of Africa’s diabetes burden; about 2.4 million South Africans lived with the disease in 2015 (IDF, Citation2015).

Available data indicate that illness may be a major impediment to seeking employment in South Africa. For example, the National Income Dynamics Study dataset shows that between 2008 and 2014, excluding individuals who were economically inactive due to full time study, sickness/disability was the major reason economically inactive respondents aged 15–54 years by 2008Footnote1 gave for economic inactivity (see ). Furthermore, illness-related inactivity had long-term implications for future job search/employment. Ninety-one percent of those economically inactive due to sickness in 2008 still did not have any desire to work in 2014 (table available on request).

Table 1. Reason for non-participation among the economically inactive.

Ascertaining the relationship between health and employment in South Africa has significant policy implications. First, South Africa has very high unemployment rates. The general unemployment rate is about 27%, a figure that is worse for females and AfricansFootnote2 (Statistics South Africa, Citation2016). Moreover, the unemployment rate among the young aged 15–24 years exceeds 50% (World Bank, Citation2015). Secondly, as earlier noted, South Africa is characterised by a high disease burden.

However, most of the studies of (un)employment determination in South Africa focus on non-health factors like education, race, and the extension of minimum wage commitments to all employers in a given sector (Kingdon & Knight, Citation2007; Banerjee et al., Citation2008). While these are very important, they are not the only determinants of employment. Thus, ascertaining the association between health and employment will shed light on another potentially important determinant of employment in the country.

Previous studies that analysed the relationship between health and (un)employment in South Africa mainly focused on HIV/AIDS. To our best knowledge, they neither examined the health measures considered in this paper, nor compared the relative importance of mental and physical health in employment determination. For instance, Arndt and Lewis (Citation2001) did not find any significant effect of HIV/AIDS on employment, while Young (Citation2005) found a significant effect in the long run. Booysen et al. (Citation2004) found some relationship between HIV/AIDS and employment in the Free State Province. McLaren (Citation2010) found that the probability of employment increased with proximity to an antiretroviral facility, while Levinsohn et al. (Citation2013) found a 6–7 percentage point positive effect of being HIV-positive on the probability of being unemployed.

None of these studies utilised a detailed nationally representative panel dataset of individuals as in this study. Therefore, they did not account for possible individual unobserved heterogeneity. Moreover, while South Africa has a substantial HIV/AIDS burden, the earlier discussion shows that non-HIV/AIDS conditions are a non-trivial component of the national disease burden. Hence, an exclusive focus on HIV/AIDS neglects key features of the country’s epidemiological profile.

2. Methods

2.1 Models

The main model is the fixed effects (FE) model that enables us to account for both observed covariates and unobserved heterogeneity. We also estimate pooled ordinary least squares (POLS) and random effects (RE) models to respectively ascertain how the estimates may differ when unobserved heterogeneity is not accounted for, and when one makes the strong assumption that the unobserved heterogeneity is not correlated with the covariates.

For the main regression, we specify employment as a function of depression, hypertension, diabetes and tuberculosis, and other explanatory variables like education, age, household size and the local unemployment rate:(1) where E and D denote employment status and depression dummies, respectively. P is a vector of physical health indicators (hypertension, diabetes and tuberculosis); and X is a vector of explanatory variables like education, household size, and a quadratic age variable (to capture possibly differing probabilities of employment across the age profile). We also control for time indicators (to account for unobserved time-varying heterogeneity). u and ε denote unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity (e.g. taste for work) and idiosyncratic error, respectively. i and t are individual and time indicators, while β denotes parameters to be estimated. Gender and race are time-invariant explanatory variables included in the RE and POLS models only. We later test the RE assumption using a robust Hausman test (Wooldridge, Citation2002). In addition, given the chronic state of unemployment among South Africans aged 15–24 years, we further disaggregate the model by age group to see if the health-employment relationship differs between this age group and their older counterparts. We also disaggregated the model by gender to ascertain if the health-employment relationship differed across gender. Given that all the models estimated in this paper are of the linear probability model (LPM) nature, we note the major shortcomings of the LPM: heteroscedasticity and probability predictions outside the unit interval. All estimates were therefore corrected for heteroscedasticity.

2.2 Data

Data came from the currently available four waves of the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) dataset. NIDS is a nationally representative panel survey of individuals, which has been conducted biennially in South Africa since 2008. Households were sampled via a stratified, two-stage cluster design. In the first stage, 400 primary sampling units (PSUs) were selected from Statistics South Africa’s 2003 master sample comprising 3000 PSUs. These 400 PSUs were sampled within 53 district council strata in a manner where the chosen PSUs were proportional to the allocation of PSUs in the master sample. Thereafter, households were randomly selected within each selected PSU and individuals in selected households were interviewed. In wave 1, 7296 households comprising 28 226 resident continuing sample household membersFootnote3 were sampled. Of these, 26 776 individuals were successfully interviewed. In wave 2, wave 3 and wave 4, 22 966, 24 329 and 25 269 respondents were successfully interviewed, respectively. A detailed description of the survey is available at www.nids.uct.ac.za

2.3 Main variables

We used two employment measures in this paper. The first measure was a dummy variable which equalled 1 if the respondent was employed (i.e. engaged in a productive activity, often for money) over the past four weeks, and zero if they were not economically active. As earlier shown in , illness/disability was apparently a non-trivial cause of economic inactivity (and therefore, employment) in South Africa. The second measure equalled 1 if the respondent was employed and zero if they were unemployed but searching for a job. These two specifications are important for at least two reasons. First, we avoid conflating both the non-economically active (NEA) and the unemployed in the same category given that they are likely systematically different from each other. Secondly, we ascertain if the relationship between the health measures used in this paper and employment operate mainly through poor health being associated with economic inactivity, or non-successful job search. As is shown, the employment measure that was largely significantly related to our health indicators was the former, apparently reinforcing the earlier point that health was strongly related to economic inactivity in South Africa (see above).

Mental health was represented by an indicator for having depressive symptoms. Depression was derived from the ten-question Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D10) index which elicits an individual’s psychological/emotional health (Andresen et al., Citation1994). The questions determined whether, in the past week, an individual felt unusually bothered, had trouble keeping their mind on what they were doing, felt depressed, felt fearful, had restless sleep, felt everything was an effort, felt lonely, could not get going, felt happy and/or hopeful about the future. Responses were calibrated into four options reflecting the frequency of occurrence as follows: rarely or none (<1 day); some or little of the time (1–2 days); occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days); and all the time (5–7 days). Per standard practice, the two positive emotions, happiness and hope, were re-coded to be similar to the negative emotions.

CES-D10 values range from 0 to 30, with increasing values indicative of poorer psychological health. Our CES-D10 index was internally consistent given a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.74 over the four waves (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1978). A value of 10 or more indicates having depressive symptoms (Andresen et al., Citation1994; Zhang et al., Citation2012). Thus, depression was a dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent’s CES-D10 index was at least 10, and zero otherwise.

The three physical health indicators were dummy variables indicating whether the individual currently suffered from hypertension, diabetes or tuberculosis over the past four weeks. An individual was classified as having a given condition if they had been diagnosed by a health professional and were either taking medication for it or (for those not taking medication), admitted to having the condition at the time of the survey.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics.

reports the descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

The estimation sample was restricted to individuals aged 15–54 years in wave 1. The upper limit of 54 years was to exclude individuals who would have exceeded 60 years (the age of eligibility for the old age pension) by wave 4. We also excluded respondents who cited full-time studies as the reason for not searching for jobs. Given that the main model was the FE model, we only included individuals who had non-missing values for all the variables in at least two waves. We excluded Indians from the analysis given their small number (there were only 414 Indians, making up only 1.2% of the pooled sample). The results remained virtually unchanged with their inclusion, and are available on request. The pooled estimation sample size was 22 859 observations.

From , 71% of the sample were employed and 26% had depressive symptoms. While 12% suffered from hypertension, 3.5% and 1.6% suffered from diabetes and tuberculosis, respectively. Given that the sample proportions for diabetes and tuberculosis were small, we excluded them in a re-specification of each model and the results remained very similar (results available on request). The average number of years of schooling was 9.6, while males constituted 47% of the sample. Average age was 38 years while the average provincial unemployment rate was 25%.

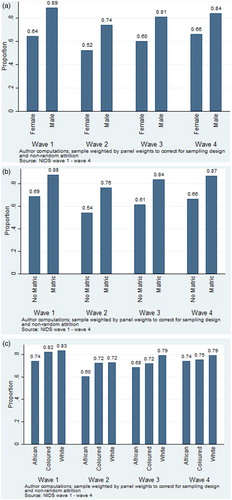

Employment probabilities over time across key characteristics: gender, education and race indicate that females, the less educated, and Africans consistently had lower employment probabilities over time (see (a) to (c)). For instance, the proportion of males employed in wave 1 exceeded that of females by 25 percentage points. It only narrowed to 18 percentage points in wave 4. The proportion of those with at least schooling (the so-called matric Footnote4) who were employed exceeded that of those with less than twelve years of schooling (no matric) by 19 and 21 percentage points in wave 1 and wave 4, respectively, indicating widening schooling premium in employment over time. The gap between whites and Africans was 9 and 5 percentage points in wave 1 and wave 4, respectively ((c)).

Figure 1: (a) Employment outcomes by gender. (b) Employment outcomes by education. (c) Employment outcomes by race.

A test of differences in proportions in employment probability across the above vectors showed that males, the matric group, and whites had significantly (p < 0.01) higher employment probabilities than females, the non-matric group and Africans, respectively, in the pooled sample (the results also held true in each individual wave). The results were similar for hypertension except for race, where the difference was not statistically significant. Also, females and the less educated had higher diabetes prevalence, while whites recorded a significantly higher diabetes prevalence than Africans. Finally, tuberculosis prevalence was statistically significantly higher among females and the less educated than males and the higher educated, respectively.

3.2. Regression results

depicts the results from the POLS, RE and FE models for both definitions of employment. Columns 1–3 depict estimates from the first definition (i.e. where employment equals 1 if the respondent was employed, and zero if she was NEA), while columns 4–6 depict estimates from the second employment definition (i.e. employment equals 1 if employed and zero if unemployed but searching for a job). In another specification, we defined the dependent variable as an economically active vs. inactive variable which equalled 1 if the respondent was either employed or engaged in job search in the reference period, and zero if she was economically inactive (discouraged or NEA). This specification was aimed at ascertaining if the health variables were negatively related with economic activity in general. The results are shown in in the Appendix and were substantively similar to those obtained in columns 1–3 of . All panel estimates were clustered at the individual level.

Table 3. The relationship between employment and mental and physical health.

For the first employment definition, the POLS and RE models indicate that having depressive symptoms was associated with a six percentage point decline in employment probability (relative to being NEA). Accounting for unobserved heterogeneity (the FE model), depression was associated with a four percentage point drop in employment probability. These estimates conformed to a priori expectations and were statistically significant at 1%. Similarly, diabetes was associated with between four and six percentage point decline in employment probability across the different specifications. Suffering from hypertension and tuberculosis was also associated with reduced employment probability. Columns 4–6 in indicate that using the second employment definition generally did not reveal any statistically significant association between most of the health measures and employment, with only depression having a significant relationship with employment in the POLS and RE models. It is worth mentioning that the FE estimates of the health measures may be attenuated. This is because these conditions (especially hypertension and diabetes) are likely to be chronic, while FE, by definition, exploits the within-variation in a variable and therefore has limited ability to identify chronic relationships.

4. Discussion

The foregoing results from both definitions of employment in suggest that, perhaps, the mechanism through which the health indicators are mostly related to employment in South Africa is through illness being associated with economic inactivity, rather than through making the search efforts of the unemployed unsuccessful. This assertion mirrors the earlier finding in , where we found that illness/disability was the dominant reason cited by economically inactive respondents (excluding those in full time study) for not looking for jobs. Given the results in , the following discussion will focus on the first definition of employment, as it appears to be the measure which is generally significantly related to the health measures of interest.

The regression results show that both mental and physical health had non-trivial relationships with employment in South Africa, while the controls also conformed to a priori expectations. Across all models, all the health measures had statistically significant negative relationships with employment, though hypertension and tuberculosis were only statistically significant in the POLS and RE models. Moreover, the health coefficients generally conformed to a priori expectations in terms of coefficient sign. Some of the health coefficients (POLS and RE coefficients of depression, and the POLS and FE coefficients of diabetes) were similar to Levinsohn et al’s (Citation2013) 6–7 percentage point effect of HIV/AIDS on unemployment in South Africa. On model choice between the RE and FE models, the robust Hausman test rejected the RE assumption, given a Sargan-Hansen Chi-square statistic of 168.81 (p < 0.01). Thus, one should focus more on the FE results. However, when interpreting the FE results, one should be mindful of the susceptibility of FE estimates to measurement error if such exists in the variables as well as the afore-mentioned potential attenuation of FE estimates in the presence of chronic health conditions.

We re-estimated the FE model to see if excluding a set of health measures significantly changed the coefficient(s) of the included health variable(s). There was no significant effect of excluding physical health indicators on the depression coefficient and vice versa. Moreover, the coefficients of other explanatory variables did not significantly change with such exclusions, indicating that the results were robust to a re-specification of the original model (see columns 1 and 2 of ). We also tested whether comorbidity was a significant feature of the health-employment relationship by interacting depression and the physical health indicators. The interactions were statistically insignificant (results available on request). This is similar to Grimsrud et al. (Citation2009), who found no evidence of comorbidity between hypertension and 12-month mental health outcomes in the absence of other chronic physical conditions in South Africa. However, they found some evidence of comorbidity between 12-month anxiety disorder and being diagnosed with hypertension (in conjunction with another chronic physical condition).

Table 4. Effect of excluding a group of health variables on employment (FE).

Another dimension of interest is gender. Columns 3 and 4 of indicate that the employment-depression relationship was similar for both females and males. Moreover, no physical health measure was significant in the disaggregated samples. However, the signs of the health coefficients generally conformed to a priori expectations.

The relationship between health and employment may differ between old and young respondents. Non-health factors (e.g. education and the general condition of the labour market) may be more important employment determinants than health for young people relative to their older counterparts. This may be true given expectedly healthier youth facing significantly higher than average unemployment rates (as noted in Section 1.2Footnote5). Moreover, different health conditions may be related to different age groups’ employment probabilities to varying degrees. In either case, one composite model may mask important features of the health-employment relationship between different age groups. Therefore, we re-estimated the FE model for those aged 15–24 years in wave 1 and their older counterparts. The results are shown in . The table indicates that of all the health indicators, only depression significantly determined youth (i.e. 15–24 years) employment. However, depression, diabetes and tuberculosis were significant in the older sub-sample. However, a Chow test of the differences in the relationships across the age categories showed no significant difference (p = 0.63).

Table 5. The relationship between employment and mental and physical health by age group (FE).

Given that we do not have sufficient information to uncover pure causality if reverse causality is a problem (e.g. instruments), we estimated the relationship between lagged health and employment by regressing employment on the lags (of various lengths) of the health indicators ().

Table 6. The relationship between lagged health and employment (OLS).

From , we see that the relationship between depression and employment extends up to two years (i.e. one lag) after the report of depressive symptoms. However, the magnitude of the relationship monotonically declined over time, suggesting that though not only a short-term phenomenon, the adverse relationship between depression and employment did not extend into the distant future. For hypertension, the relationship extended even up to six years after reporting illness, while the relationship actually became stronger over time. This shows that the deleterious relationship between hypertension and employment apparently became increasingly more important over time. Diabetes and tuberculosis also showed extended relationships with employment, though the relationships did not monotonically rise over time as in the case of hypertension. An important message from these results is that the health-employment relationship is not only of a short-term nature but persists into the future, especially for the physical health indicators.

We also estimated OLS regressions to ascertain the relationships between transitions into depression and hypertension (from not suffering from them in a prior wave) and transitions into economic inactivity (from being previously employed). The results generally conformed to a priori expectations given that adverse health transitions were associated with transitions into economic inactivity over time. However, none of the transitions was statistically significant at conventional levels (results available on request).

5. Conclusion

This study found that all four health conditions included in the analysis (both mental and physical health) negatively predict employment in South Africa, with depression and diabetes statistically significant across all model specifications (i.e. POLS, RE and FE). Moreover, depression negatively determines employment both for the youth (aged 15–24 years in wave 1) and their older counterparts, as well as for both males and females, while diabetes and tuberculosis also significantly determine employment for the older sample (aged 25–54 years in wave 1). As earlier indicated, it is likely that the FE estimates of the health conditions represent a lower bound of the health-employment relationship. This is especially more likely for hypertension and diabetes given their chronic nature. We also found that the health-employment relationship is not merely a contemporaneous phenomenon, but generally extends well into the future, especially for the physical health indicators. The above results also suggest that the health-employment relationship as investigated in this paper seems to mainly operate through poor health being associated with people remaining economically inactive, rather than in preventing the searching unemployed from getting jobs. In general, the results in this paper suggest that though both mental and physical health are negatively related to employment, (chronic) physical illness appears to have a stronger negative relationship with employment than depression in South Africa (especially over time).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 The upper age limit was to exclude potential recipients of the old age pension by 2014.

2 South Africa has four main racial groups: Africans, coloureds (mainly of mixed ancestry), Indians and whites.

3 Continuing sample members (CSMs) are wave 1 resident household members and the children of female CSMs who join the sample in subsequent waves. An individual qualifies for residence in a household if she satisfies the following three conditions: (i) Has lived in the homestead at least fifteen days in the last twelve months or arrived there within the last fifteen days and the homestead was now their usual residence; and (ii) Shares food from a common source with other household members when they are together; and (iii) Contributes to, or shares in a common resource pool.

4 ‘Matric’ is a colloquial term implying roughly 12 years of schooling in South Africa.

5 Also, statistical tests (available on request) indicate that those aged 25+ years in wave 1 had a higher prevalence of each of the health conditions, but were more likely to be employed than their younger counterparts in each wave (p < 0.01).

References

- Andresen, EM, Malmgren, JA, Carter, WB & Patrick, DL, 1994. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 10(2), 77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6

- Arndt, C & Lewis, JD, 2001. The HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa: Sectoral impacts and unemployment. Journal of International Development 13(4), 427–49. doi: 10.1002/jid.796

- Banerjee, A, Galiani, SF, Levinsohn, JA, McLaren, Z & Woolard, I, 2008. Why has unemployment risen in the new South Africa. Economics of Transition 16(4), 715–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0351.2008.00340.x

- Booysen, FR, Bachmann, M, Matebesi, Z & Meyer, J, 2004. The socioeconomic impact of HIV/AIDS on households in South Africa: Pilot study in Welkom and Qwaqwa, Free State Province. University of the Free State.

- Chirikos, TN, 1993. The relationship between health and labor market status. Annual Review of Public Health 14(1), 293–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.14.050193.001453

- Das, J, Do, Q, Friedman, J, McKenzie, D & Scott, K, 2007. Mental health and poverty in developing countries: Revisiting the relationship. Social Science & Medicine 65(3), 467–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.037

- Forouzanfar, MH, Liu, P, Roth, GA, Ng, M, Biryukov, S, Marczak, L, Alexander, L, Estep, K. et al., 2017. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990–2015. JAMA 317(2), 165–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19043

- Grimsrud, A, Stein, DJ, Seedat, S, Williams, D & Myer, L, 2009. The association between hypertension and depression and anxiety disorders: Results from a nationally-representative sample of South African adults. Plos One 4(5), e5552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005552

- Habyarimana, J, Mbakile, B & Pop-Eleches, C, 2005. HIV/AIDS, ARV treatment and worker absenteeism: evidence form a large African firm. Georgetown University, Mimeo.

- IDF, 2015. IDF diabetes Atlas. 7th ed. International Diabetes Federation. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/

- Jack, W & Lewis, M, 2009. Health investments and economic growth: Macroeconomic evidence and microeconomic foundations. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no.4877.

- Kingdon, G & Knight, J, 2007. Unemployment in South Africa, 1995 2003: Causes, problems and policies. Journal of African Economies 16(5), 813–48. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejm016

- Knaul, FM, 2001. Linking health, nutrition, and wages: The evolution of age at menarche and labor earnings among adult Mexican women. Inter-American Development Bank 582(4), 63–86.

- Levinsohn, J, McLaren, ZM, Shisana, O & Zuma, K, 2013. HIV status and labor market participation in South Africa. The Review of Economics and Statistics 95(1), 98–108. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00237

- Lloyd-Sherlock, P, Beard, J, Minicuci, N, Ebrahim, S & Chatterji, S, 2014. Hypertension among older adults in low- and middle-income countries: Prevalence, awareness and control. International Journal of Epidemiology 43(1), 116–28. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt215.

- Lloyd-Sherlock, P, Ebrahim, S & Grosskurth, H, 2014. Is hypertension the new HIV epidemic? International Journal of Epidemiology 43(1), 8–10. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu019.

- McLaren, Z. 2010. The effect of access to AIDS treatment on employment outcomes in South Africa. (Unpublished).

- Nunnally, JC & Bernstein, IH, 1978. Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Nwosu, CO, 2015. An analysis of the relationship between health and the labour market in South Africa. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cape Town.

- Nwosu, CO & Woolard, I, 2017. The impact of health on labour force participation in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics [online]. doi:10.1111/saje.12163.

- Patel, V & Kleinman, A, 2003. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81(8), 609–15.

- Paul, KI & Moser, K, 2009. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior 74(3), 264–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001

- Ross, MH & Murray, J, 2004. Occupational respiratory disease in mining. Occupational Medicine 54(5), 304–10. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqh073.

- SADAG, 2015. The impact of depression at work. http://www.sadag.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2391:new-research-on-depression-in-the-workplace&catid=11:general&Itemid=101

- Savedoff, WD & Schultz, TP, 2000. Earnings and the elusive dividends of health. Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC.

- Schultz, TP, 2002. Wage gains associated with height as a form of health human capital. American Economic Review 92(2), 349–53. doi: 10.1257/000282802320191598

- Statistics South Africa, 2016. Quarterly labour force survey quarter 1: 2016. (P0211). Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Thomas, D & Frankenberg, E, 2002. Health, nutrition and prosperity: A microeconomic perspective. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80(2), 106–13.

- Vos, T, Allen, C, Arora, M, Barber, RM, Bhutta, ZA, Brown, A, Carter, A, Casey, DC et al. 2016. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. The Lancet 388(10053), 1545–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6

- Wooldridge, JM, 2002. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- World Bank, 2015. Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15–24) (modeled ILO estimate). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS?locations=ZA

- World Health Organization, 2013. A global brief on hypertension: Silent killer, global public health crisis.

- World Health Organization, 2014a. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization, 2014b. Non-communicable diseases country profile: South Africa. http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/zaf_en.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization, 2016a. Global report on diabetes.

- World Health Organization, 2016b. Global tuberculosis report 2016. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization, 2017a. Depression fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- World Health Organization, 2017b. Gender and women’s mental health. http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/

- Young, A, 2005. The gift of the dying: The tragedy of AIDS and the wealth of future African generations. Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(2), 423–66.

- Zhang, W, O’Brien, N, Forrest, JI, Salters, KA, Patterson, TL, Montaner, JS, Hogg, RS & Lima, VD, 2012. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PloS One 7(7), 1–5.