ABSTRACT

Family is the foundation on which other institutions are built. Its quality has resultant effects on the quality of the society in its entirety. It is, therefore, expedient to examine the relationship between diverse family forms and quality-of-life in sub-Saharan African countries. Demographic and Health Surveys for four countries were used for the study. The study reveals a significant relationship between cohabitation, marriage and wealth status in all the four countries, while marriage remains significantly related with education in all the countries except Kenya. Poisson regression revealed a higher effect of education on diverse family forms except single parents in Mozambique and Nigeria, while with the adjusted data divorce/separated women in Kenya have a significantly higher coefficient (β = −1.03, p-value = 0.000) compared with other countries in the study area The study concludes that family formation cannot be overlooked, as it relates to the wellbeing of women in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

The family is one of the oldest fundamental institutions in society. It provides both biological and social stability for its members. It is the foundation on which other institutions are built. Consequently, its quality has resultant effects on the quality of the society in its entirety. Families are also the centre of consumption, savings and other production activities that are essential to the overall economic wellbeing of the nation. The society or the nation depends on this essential unit, where value and norms are developed. Until the present time, the family has been characterised by a relative degree of normative structure, and certain duties and privileges have been prescribed for husbands, wives, children, fathers and mothers. These duties and positions have been defined by powerful cultural values and they include provider, house-keeper, child-care, child socialisation, recreational, kinship, therapeutic and sex roles. Talcott and Robert (Citation1955) analysed the primary roles of males and females along the instrumental–expressive dimension. His functional analysis of the family includes the allocation of roles according to sex within the family. The family role entails leadership and decision-making responsibilities filled by the spouse, who is the economic provider for the family, the husband/father. The wife/mother then assumes the expressive role of caring for children and doing the housework

There has been a dramatic shift from the traditional nuclear family life in recent decades and never-married women have been on the increase in the last two decades. Coupled with changes in family-related behaviours (such as an increase in pre-marital sex), cohabitation and non-marital childbearing have occasioned dramatic increases in the social acceptance of all these behaviours (Axinin & Thornton, Citation2000; Cancian & Reed, Citation2009). Manning (Citation2015) explained that cohabiting families have increased from 20% in the 1980s to over 40% in the 2000s in the US. This has resulted in a decline in the number of children with both biological parents in residence. In 2013, about 5 million children were living with cohabiting parents before age 12 and 40% of American children have spent part of their lives with cohabiting families (Manning, Citation2015). However, while the relationship between family structure and economic wellbeing is well documented, poverty varies within different family structures. Cancian et al. (Citation2011), in their study conducted in the US in 2006, revealed that about 40% of single mother families, 8% of married couples with children and 14% of single fathers families were poor. Evidence also suggests that having a child before getting married increases the probability of poverty. Poverty also increases the chances of non-marital childbearing, stability of marriages and, for those who divorce, the probability of remarriage (Cancian & Reed, Citation2009). Sawhill and Thomas (Citation2002) revealed that the poverty rate will be four times higher among single-parent families compared with two-parent families. The fact remains that single mothers have limited financial resources in settling different bills such as education, health and childcare costs. In the US, seven out of every 10 children living with single mothers are poor compared to one-third of those who are living with other types of families (Mather, Citation2015). This is as a result of the number of adults that are capable of participating in paid employment. Increase in male unemployment, reduction in ‘marriageable men’ and marital breakdown have also resulted into the increase in female-headed households, which invariably affects the quality-of-life (Lerman, Citation1996). Moreover, while the pattern of cohabitation and marriage differs according to social class, it is expected that marriage should improve life satisfaction and improve quality-of-life over cohabitation due to the contractual agreement, which indicates the mutual rights and benefits. Brien and Sheran (Citation2003) revealed that family formation will affect the wellbeing in relation to the sharing of resources. They explained that mutual financial responsibility will provide a good atmosphere for division of labour and a higher standard of living. It is also expected that, in a dual-breadwinner household, income received by one of the partners may serve as a ‘rescue means’ for the other partner in the case of job loss. Kaplan and Lancaster (Citation2003), in their study, explained that the quality-of-life and wellbeing derived from family formations may differ between men or women, married or unmarried as a result of gender differences and the motive behind the relationship. They are of the opinion that females benefit more than males in long-term relationships due to the financial protection and support in raising children, which makes them support monogamy. Studies also found that there may be a delay in marriage or more women who are single in areas where women have higher employment and earnings (South & Lloyd, Citation1992; Blau et al., Citation2000). It was expected that women’s earnings and higher employment opportunities should have a positive impact on family formation and discourage gender specialisations as regards income in marriage (Goldstein & Kenney, Citation2001). Looking at divergent views and the dearth of literature in the area of family formation and quality-of-life in Africa, it is, therefore, expedient to examine the relationship between diverse family forms and quality-of-life among women in sub-Saharan African countries.

Family forms in sub-Saharan Africa: the current trend

In the last two decades, family structures have witnessed demographic changes around the world, from the extended family to nuclear family, with an increase in divorce or separation, with the emergence of new family formations such as cohabitation instead of marriage, single-parenting, blended families and living-apart-together (Kimani & Kombo, Citation2010). Although the African family is traditionally organised along gender line and characterised by male domination, marriage is the centrality of the family, with unions between lineages which provide the power for the patriarchal heads. These families have grown from the simple, ancient entities that existed in foraging societies to the modern entities that emerged with industrialisation (Leeder, Citation2004). It was also observed that urbanisation influenced the shift from the kinship obligations and societal control. Coupled with this are the level of education and employment opportunities, especially in the urban centres, which allow women to escape the pressure from being in a marital union. The enhancement of women’s status as a result of money economy and the opportunity of working outside the home for women considerably changed the forms and functions of the African family. Studies revealed a decline in marriage in Africa and a progressive increase in the other forms of family formation (Ikamari, Citation2005). For instance, a study on cohabitation in sub-Saharan African shows that 10% of women in the age group 15–19 years cohabited in South Africa and Namibia, while seven out of every 10 women in the same aged group cohabited in West and East Africa. Single motherhood, which may be as a result of pre-marital motherhood and divorce or death of husband, is also on the increase in the continent. It was reported that 50% of women in sub-Saharan African will become single as a result of widowhood or divorce (Clark & Hamplova, Citation2013). Tilson and Larsen (Citation2000) reveal that 45% of first marriages in Ethiopia end up in divorce within 30 years and two thirds of the divorces took place within the first 5 years. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the number of divorces or separation increased by 50% between 1984 and 2007. In countries like Nigeria, where divorce is very uncommon, the recent 2013 NHDS data indicates an increase in divorce rate. However, this cannot be compared with countries like Ghana and Togo, where more than 50% of their first marriages end up in divorce (Gage & Njogu, Citation1994; Takyi & Gyimah, Citation2007; Locoh & Thiriat, Citation1995). There are also variations relating to single parenting in countries like Zimbabwe, Ghana and Burundi, where more than 10% of births are to never-married women in the age group 15–24 years. In South Africa, never-married women contributed about half of all births to women between ages 12–26 (Gage-Brandon & Meekers, Citation1993; Garenne et al., Citation2000). Some of the reasons identified for the increase in the rate of divorce include infertility, religion, level of education and poor economic conditions.

However, Makomani (Citation2011) explained that the dramatic changes in the socio-economic situations of African countries have led to union instability and well-being of families. In his study in Botswana, it was revealed that cohabitated women did not have legal protection with respect to inheritance, property and maintenance rights. Also, children born within these unions are vulnerable, with no claims with regards to their father’s property in a situation where the union ends. Studies reaffirmed that female-headed household in Africa are more pronounced among the poor. Single parents are more likely to be poor due to low earning capacity, which cannot be compared with the married women (Blanc & Lloyd, Citation1994; Sean, Citation1999). They normally have little or no financial support, with antecedent consequences such inadequate childcare, poverty and psychological difficulties. McLoyd et al. (Citation1994) revealed that financial stress is a predictor of depression among single mothers, they often experience a cycle of bleakness and hopelessness which is detrimental to their health. The paucity of literature in this area of family formation and quality-of-life also necessitated this study

Methods

Demographic and Health Surveys for four countries were used for the study. The four selected countries are representative of the regions within Sub-Saharan Africa which has data for a minimum of 15 years. East Africa is represented by Kenya, while Nigeria is selected from West Africa. South Africa has Mozambique as a representative, while Congo Brazzaville was selected for Central Africa. This is to allow comparisons among the regions. The dataset for women aged 15–49 years were downloaded after the explicit permission from Measures DHS had been gained.

In this study, women with at least one living child (≤ 5 years) were used to categorise diverse family forms, while women who are widows were excluded from the categorisation, since the death of the husband may demand the need to remarry. The sample size from the four countries were Congo Brazzaville 6037 respondents, Kenya 10 350, Mozambique 1035 and Nigeria 27 034.

For quality-of-life, the Objective Approach by United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Index (HDI) (UNDP, Citation2004) was used. Based on this index, knowledge (years of schooling) and standard of living (wealth index) were used in this study. For years of schooling, education in single years was used due to the fact that there is a high correlation between highest levels of education and wealth index. Wealth index was recoded into poor and rich. Four different categories of family formation were identified. These are Single Parenting (these are women who are not presently with a partner or who have child(ren) out of wedlock), Married, Cohabitation (those who are living with a partner but not married) and Divorced/Separated (they have married before, but not with partner at the time of the survey). Proximate controls are age, place of residence, partners’ education, age at first cohabitation, number of living children and religion. These variables were identified in the literatures to have an effect on diverse family forms. The independent variable was a categorical variable and it was recoded through the dummy variable where each category was recoded as ‘yes’ = 1, ‘otherwise’ = 0. This was employed to determine the effects of each category in the multivariate analysis. Two models were developed to determine the effects of the diverse family forms on the well-being of the respondents which is the main objectives of the study. This was also based on the two variables that were used to measure quality-of-life. For the first model, binary logistic regression was used where wealth index was recategorized from five categories (poor, poorest, middle, richer and richest). The richer and richest were merged together, while the other three categories were also merged together as poor. This was dichotomised into two, ‘rich’ = 1 and ‘poor’ = 0. The data for the four countries were also pooled together to show the holistic effects of the independent variables on dependents variable. Given that years of schooling is a count variable, Poisson regression technique was used in the construction of the second model. Univariate analysis was also adopted to see the trends (1998–2015) of the variables included in the models for all the countries selected and the variations among each of them.

Results

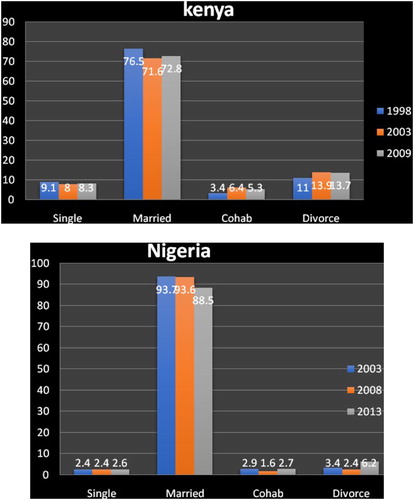

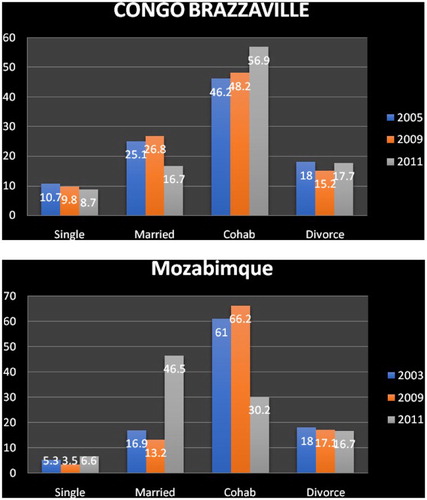

The study reveals from that one-fifth of women in the four selected countries were in the age group 20–29 years, even with the pooled data, while Nigeria has the highest number of women in the age group 45–49 years (9.1%). Ironically, Nigeria has the highest for both women with no level of education and higher education; 43.5% and 7.6%, respectively. Congo Brazzaville and Kenya, however, had the highest percentage of women with secondary (53.4%) and primary education (54.3%), respectively. More than two-thirds of the women in the selected countries live in rural areas (65.4%). With respect to the wealth index, which is one of the variables used to measure the quality-of-life, the study indicated that 67.4% of women in Congo Brazzaville are poor, while the Mozambican women are the richest (51.1%), followed by Kenyans (45.2%). In relation to the age at first cohabitation, Nigeria has the highest number of cohabiting women before age 14 years (26.6%), followed by Mozambique (15.8%), while more than two-thirds of women in the study area would have cohabited before aged 19 years when the data were pooled together. On family size, the total children ever born (CEB) shows that Nigeria has the highest number of women who had given birth to seven children and above. With regards to labour force participation, Congo Brazzaville (80.6%) has the highest number of women who are currently working, while Mozambique has the least number of women (42.6%) who are currently working. The trends of family formation vary within the selected countries. In Nigeria, for example, single parents decreased from 37.5% in 2003 to 2.6% in 2013, while the number of married women increased from 54.5% in 2003 to 88.5% in 2013. In Congo Brazzaville, women who cohabitated increased from 46.2% in 2005 to 56.7% in 2011, while women who cohabited in Mozambique decreased from 66.2% in 2009 to 30.2% in 2011 ().

Figure 1. Charts Showing Diverse Family Forms in Selected Sub-Saharan African Countries.

Table 1. Percentage distribution of selected variables.

The binary logistics regression in reveals that single parents and married women are significantly related with wealth index in the unadjusted data among women in Congo Brazzaville (p-value = 0.028 and p-value = 0.004, respectively). The three family structures are more likely to have rich wealth status (Single parents Odds Ratio = 2.176, Married Odds Ratio = 4.590, Cohabitation Odds Ratio = 2.130) in the adjusted data compared with the reference category, which is divorce/separated. Among Kenyan women, those who are married and those who cohabited were negatively significantly related with wealth index when compared with the reference category. In the unadjusted model all the categories were significant in Mozambique. With the unadjusted data in Nigeria, the three family structures were significantly related with wealth index (p-values < .005), while those who cohabited are 2.280-times more likely to have a rich wealth index when compared with the reference category divorce/separated. However, with the adjusted data in , all the three family structures in Congo Brazzaville and Mozambique were significantly related with wealth index (p-values < 0.0001), while none of the family structures was significant with the wealth index in Kenya. With respect to Nigeria, except single parents, other family structures were significantly related with the wealth index (p-values < 0.0001) and more likely to have good wealth status when compared with the reference category. With the pooled data (), only single parents are significantly related with the wealth index with the unadjusted data, while all the family structures were significantly related with wealth index with the adjusted data (p-values < 0.0001).

Table 2. Logistics regression showing relationship between family formation and wealth index.

Table 3. Logistics regression showing relationship between family formation and wealth index (pooled data).

shows the Poisson regression of knowledge diverse family forms and (education in single years) in the study area. The family structure in all the four countries shows a statistically positive relationship with education except cohabitation in Nigeria with unadjusted data. Married women in Mozambique exhibit a higher coefficient with education (β = −7.091, p-value = 0.000) when compared with other countries in the unadjusted data. When the equation was adjusted with the confounding variables, Cohabiting women in Congo had a significantly higher coefficient (β = 2.411, p-value = 0.000) compared with other countries in the study area. Single women showed a significant relationship with the year of schooling in Nigeria and Mozambique with adjusted data. The results also displayed a significant relationship between family formation and years of schooling unadjusted data, except for with the cohabitation women in Nigeria. In Kenya, except married women, other family forms were insignificant with the years of schooling. With the pooled data, cohabiting women had a higher coefficient in both adjusted and unadjusted data ().

Table 4. Poisson regression showing relationship between family formation and education.

Table 5. Poisson regression showing relationship between family formation and education (pooled data).

Discussion

The paper examined the relationship between diverse family formation and quality-of-life among women in sub-Saharan Africa. Using the latest Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data, except in Kenya, where 2014 data were not available as at the time of this study, the analyses reveal that half of the women married before 19 years of age. It is evident that early marriage thrives in sub-Saharan Africa countries. This finds corroboration in existing studies. Mozambique, for instance, has nearly 60% of girls with no education married before aged 18 years, while 82% of girls with no education married before aged 18 years in Nigeria (International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), Citation2012). In most of these countries girls are seen as an economic burden and a means of alleviating household poverty and improve the family’s well-being. Early marriages, however, entrap girls in the cobweb of poverty. UNICEF (Citation2005) explained that 40% of girls from the poorest household are more likely to get married before 18 years of age, which will further impoverish them. Studies also argued that women who married early may not have the emotional strength for the challenges associated with marriage and this may lead to divorce (Takyi & Gyimah, Citation2007; Adegoke, Citation2010). The high number of women with no education in Nigeria and Mozambique may find resonance with the prevalence of early marriages. Uneducated girls are three times more likely to get married before age 18 years compared to those with secondary education or higher education (UNFPA, Citation2012). It is evident that education has played an important role in recent times in changing women’s attitudes towards marriage, age at marriage, childbearing and union formation. More than one-third of the respondents were in a poor wealth quartile, most of these women in sub-Saharan Africa are self-employed, with low returns on their businesses, compounded with large family size. Cancian and Reed (Citation2009), in their study, explained that the number of adults in a household, the employment status, types of earnings, wage rates and number of children to support will influence the income status of women in any union. More than one-third of these women have more than four children and are currently not working. Furthermore, there are mixed revelations with regard to the trends of family formation, for instance in Mozambique the number of married women nearly tripled between 2003 and 2011, while cohabiting reduced from 66% in 2009 to 30.2% in 2011. This may be as a result of an increase in the level of education of women above primary school level, from 9.7% in 2003 to 23.3% in 2011 (MDHS, Citation2011). The case is reversed in Congo Brazzaville, with a cohabitation increase from 46.2% in 2005 to 56.7% in 2011.

This study established significant relationship between cohabitation, marriage and wealth status in the four countries, while single parents were significant in Congo and Mozambique for both adjusted and unadjusted data. Union formation improves the quality-of-life of women. Partnerships have positive effects on life satisfaction, discourage risky behaviour and promote healthy living. Marriage and cohabitation provide an avenue for pooling the resources together and sharing of responsibility. Haring-Hidore et al. (Citation1985), in reviewing 58 studies, discovered that there is a positive association between being married and well-being, while those who cohabited are less likely to have good quality-of-life when compared with married couples. Kohler et al. (Citation2005) explained that having a spouse improves the quality-of-life for both genders, but the effect is almost twice for men than women. They believed that men seem to enjoy greater benefit in terms of wellbeing from partnerships than women. While cohabitation has a direct impact on life satisfaction, similar to that of marriage, the magnitude of the effect is very low compared to married partners. It was also believed that, apart from the family formation, other factors like education and cultural factors will influence women’s wellbeing in any union. Stutzer and Frey (Citation2006) identified level of education between couples as a factor that can influence life satisfaction and quality-of-life, those couples with small educational differences gain more satisfaction than those couples with large differences in educational attainment. Except in Kenya, marriage remains significantly related with education in all the countries when considered with other variables.

An increase in the years of schooling will increase the knowledge of women and enable them to make better choices and decisions on spousal preferences, which will eventually determine family formation. Studies have shown that education has a bidirectional effect on family formation (Brienna, Citation2006, Geruso & Royer, Citation2014). Bernhard and Tabuchi (Citation2012), in their study on the effects of education on family formation among women, reported that the increasing opportunities for educated women in the labour market and the available economic resources to satisfy needs may lead to a delay in family formation, decreased nuptiality but not childlessness. The pursuing of higher education among women will influence family formation and having a first child. Education provides other opportunities for motherhood than childbearing and, consequently, reduces the fertility level

Conclusion

The study reaffirmed the association between family forms and quality-of-life among women in sub-Saharan African countries. The inverse relationship between cohabitation and marriage with the years of schooling was established in this study. Improved quality-of-life of women through higher occupational status and a better opportunity to fulfil their labour market desires are guaranteed through higher educational attainment. It is clear, therefore, that family formation cannot be overlooked, as it relates to the well-being of women in sub-Saharan Africa. In order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, which is basically on healthy lives and promotion of wellbeing for all. It is necessary for a policy that will increase the years of schooling for girls. This will increase their access to knowledge and enable them to make right choices that will improve their wellbeing. The Government of these countries should also promote two-parent families, which will improve the quality-of-life for women. It is also of the opinion that the data for this study did not exhaust most of the variables for quality-of-life, and further study will be necessary to see the relationship between diverse family forms in sub-Sahara Africa and other variables.

Acknowledgement

The support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CoE in Human Development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Adegoke, T, 2010. Socio-cultural factors as determinants of divorce rates among women of reproductive age in ibadan metropolis, Nigeria. Studies of Tribes and Tribals 8(2), 107–14. doi: 10.1080/0972639X.2010.11886617

- Axinn, WG & Thornton, A, 2000. The transformation in the meaning of marriage. In Waite, L, Bachrach, C, Hindin, M, Thomson, E & Thornton, A (Eds.), Ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. Aldine de Gruyter, New York, pp. 147–65.

- Bernhard, N & Tabuchi, R, 2012. One or two pathways to individual modernity? The effects of education on family formation among women in Japan and Germany. In Vienna yearbook of population research, vol. 10, education and the global fertility transition, 49–76. Vienna Institute of Demography, Vienna.

- Blanc, AK & Lloyd, CB, 1994. Women’s work, child-bearing and child-rearing over the life cycle in Ghana. In Adepoju, A & Oppong, C (Eds), Gender, work, and population in sub-Saharan Africa, 112–31. James Currey, London.

- Blau, FD, Kahn, LM & Waldfogel, D, 2000. Understanding young women’s marriage decision. The role of labour and marriage married condition. Industrial & Labour Relations Review 53(4), 624–47. doi: 10.1177/001979390005300404

- Brien, M & Sheran, M, 2003. The economics of marriage and household formation. In Grossbard-Shechtman, S (Ed.), Marriage and the economy. Theory and evidence from advanced industrial societies. Cambridge University Press, New York and Cambridge.

- Brienna, P-H, 2006. The changing effects of education on family formation during a period of rapid social change http://paa2006.princeton.edu/papers/60440.

- Cancian, M & Reed, D, 2009. Family structure, childbearing, and parental employment: Implications for the level and trend in poverty. Focus 26(2), Fall, 1–6.

- Cancian, M, Meyer, DR & Cook, ST, 2011. The evolution of family complexity from the perspective of nonmarital children. Demography 48, 957–82.

- Clark, S & Hamplova, D, 2013. Single motherhood and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: A life course perspective. Demography 50, 1521–49. doi:10.1007/s13524-013-0220-6.

- Gage, A & Njogu, W, 1994. Gender inequalities and demographic behavior. Population Council, New York.

- Gage-Brandon, A & Meekers, D, 1993. Sex, contraception and childbearing before marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. International Family Planning Perspectives 19(1), 14–33. doi: 10.2307/2133377

- Garenne, M, Tollman, S & Kahn, K, 2000. Premarital fertility in rural South Africa: A challenge to existing population policy. Studies in Family Planning 31(1), 47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00047.x

- Geruso, M & Royer, H, 2014. The impact of education on family formation: Quasi-experimental evidence from the UK https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/geruso_royer.pdf.

- Goldstein, JR & Kenney, CT, 2001. Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review 66, 506–19. doi: 10.2307/3088920

- Haring-Hidore, M, Stock, WA, Okun, MA & Witter, RA, 1985. Marital status and subjective well-being: A research synthesis. Journal of Marriage and the Family 47(4), 947–53. doi: 10.2307/352338

- ICRW, 2012. Child marriage in southern asian: Policy options for action. ICRW, Washington, DC.

- Ikamari, LDE, 2005. The effect of education on the timing of marriage in Kenya. Demographic Research 12(1), 1–28.

- Kaplan, H & Lancaster, J, 2003. An evolutionary and ecological analysis of human fertility, mating patterns, and parental investment. In Wachter, KW & Bulatao, RA (Eds), Offspring: human fertility behavior in biodemographic perspective, 170–223. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

- Kimani, E & Kombo, K, 2010. Challenges facing nuclear families with absent fathers in Gatundu North District Central Kenya 10(2), 11–25.

- Kohler, H-P, Behrman, JR & Skytthe, A, 2005. Partner + children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Population and Development Review 31(3), 407–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00078.x

- Leeder, EJ, 2004. The family in global perspective: A gendered journey. SAGE Press, Thousand Oaks, CA, 307 pp.

- Lerman, R, 1996. The impact of the changing US family structure on child poverty and income inequality. Economica 63, 5119–39. doi: 10.2307/2554812

- Locoh, T & Thiriat, MP, 1995. Divorce et Remariage des Femmes en Afrique de l'Ouest - Le Cas du Togo. Population 50(1), 61–93. doi: 10.2307/1533793

- Makomani, Z, 2011. Dynamics of non-marital cohabitation in Botswana. Lap Lampert Academic Publishing. Pgs 168.

- Manning, WD, 2015. Cohabitation and child wellbeing. The Future of Children 25(2), 51–66. doi: 10.1353/foc.2015.0012

- Mather, M, 2015. U.S. children in single-mother families Population Reference Bureau, Data Brief. May, Washington.

- McLoyd, VC, Jayaratne, TE, Ceballo, R & Borquez, J, 1994. Unemployment and work interruption among African American single mothers: Effects on parenting and adolescent socioemotional functioning. Child Development 65, 562–89. doi: 10.2307/1131402

- MDHS, 2011. Mozambique Demographic and Health Survey 2011 Report. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr266-dhs-final-reports.cfm

- Sawhill, I & Thomas, A, 2002. For richer or for poorer: Marriage as an antipoverty strategy. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21(4), 587–99. doi: 10.1002/pam.10075

- Sean, J, 1999. Singlehood for security: Towards a review of the relative economic status of women and children in woman-led households. Society in Transition 30(1), 13–27. doi: 10.1080/10289852.1999.10520165

- South, SJ & Lloyd, KM, 1992. Marriage opportunities and family formation: Further implications of imbalanced sex ratios. Journal of Marriage and Family 54, 440–451. doi: 10.2307/353075

- Stutzer, A & Frey, BS, 2006. Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics 35, 326–47. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.043

- Takyi, B & Gyimah, S, 2007. Matrilineal family ties and marital dissolution in Ghana. Journal of Family Issues 28(5), 682–705. doi: 10.1177/0192513X070280050401

- Talcott, P & Robert, B, 1955. Family, socialization and interaction process. Glencoe, IL, Free Press.

- Tilson, D & Larsen, U, 2000. Divorce in Ethiopia: The impact of early marriage and childlessness. Journal of Biosocial Science 32(3), 355–72. doi: 10.1017/S0021932000003552

- UNDP, 2004. Human Development Report 2004. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2004

- UNICEF, 2005. Early marriage: A harmful traditional practice – A statistical exploration. UNICEF, New York.

- UNFPA, 2012. Marrying too young: End child marriage. Published by the United nations Population Fund UNFPA, New York.