ABSTRACT

The township cash economy of fast food, takeaways, and prepared meals is collectively termed ‘informal foodservice’. An analysis of a five-township ∼3800 microenterprise census, and qualitative supply chain investigation of 50 informal foodservice retailers and 75 consumers revealed a well-established although deeply informal trade predominated by women preparing takeaway foods and conducting street braai (BBQ). The business demonstrates high dependence on the immediate place of operations which includes local input suppliers and selling to a narrow pool of trade from immediate (walking scale) neighbourhoods. Supply chains are short, linked to formal agriculture and wholesale sectors. Informal foodservice is heavily utilised by local residents on a regular basis who spend up to R218 per week on products (potentially 30% of income) from these outlets. These enterprises make a substantial contribution towards satisfying local food demand whilst serving an important social protection and neighbourhood relationship function.

1. Introduction

The informal economy provides livelihoods for thousands of South Africans and an important food access for the poor. An important informal business activity of Cape Town, South Africa, is the preparation and trade of food as takeaways, meals and catering (collectively described in this paper as ‘informal foodservice’). A microenterprise census of five working class township settlements by Charman et al. (Citation2017) demonstrates its strong economic basis in the trade of food, takeaways, and drink (collectively over 50% of enterprises by number). Yet, despite the increasingly recognised role of informal foodservices for food security, especially for poor urban dwellers (Cohen & Garret, Citation2009) the understanding of activities, mechanisms and the trade environment within urban townships remains limited (Even-Zahav & Kelly, Citation2016). Informal foodservice supports self-employment, local economic development and enhances food security in culturally and geographically important ways (Cohen & Garret, Citation2009; Crush & Frayne, Citation2011; Skinner & Haysom, Citation2016). This paper contains a review of informal food economy knowledge and identifies several theoretical questions and knowledge gaps. It further analyses data from a small-area business census and presents the findings of subsequent qualitative research conducted with a sub-sample of informal microenterprise operators and informal foodservice customers. The paper concludes by reviewing the implications for the wider theoretical discourse around the informal food economy, thus building on the state of knowledge on the nature and operations of microenterprises in the informal foodservice sector and their role in livelihoods and food security.

2. Background

In developing countries throughout the world, and especially in sub-Saharan Africa, many people’s livelihoods are enmeshed in what is often referred to as the informal economy. The category ‘informal sector’, first coined by anthropologist Keith Hart in a 1971 study of low-income activities in Ghana (Hart, Citation1973, 68), has become a catch-all for a wide range of economic activities which share a few key characteristics: they are unregistered for tax, they are unregulated, and they do not offer employees any social benefits (Chen, Citation2012).

Four main schools of thought contest the characteristics and causes of informal work. Dualists maintain that informal operators are excluded from economic opportunities as a result of disparities between population growth rates and industrial employment as well as between people’s skills and economic opportunities (Hart, Citation1973). This is considered untenable in South Africa due to the close linkages between formal and the informal economies (Devey et al., Citation2003; Greenberg, Citation2010; Du Toit & Neves, Citation2014; Greenberg, Citation2016). Reviews of the informal food economies in Cape Town (Battersby & Marshak, Citation2016) and Johannesburg (Kroll, Citation2016) indicate that the informal sector is indeed closely linked with the formal sector as the key source of produce. By contrast, structuralist explanations contend that informality is a necessary outcome of capitalism as formal firms externalise operations and risks to the informal domain (Moser, Citation1978; Chen, Citation2012). The legalist position argues that the self-employed operate informally to avoid hostile legal systems which favour large and powerful corporations (Chen, Citation2012). This is confirmed to some extent by informal trade research in Durban, where harassment by police appeared commonplace (Mkhize et al., Citation2013). Finally, voluntarists assert that informal operators deliberately avoid regulation, registration and taxation, following a rational cost–benefit calculation though not simply because of onerous registration procedures. The diversity of the informal economy suggests that each of these positions may reveal valid perspectives (Chen, Citation2012).

In sub-Saharan Africa, the informal sector comprises some 66% of non-agricultural employment. Trade forms the dominant activity, constituting 43% of total informal economic activity. Comparatively the informal economy makes up 82% of non-agricultural employment in South Asia, 65% in East and Southeast Asia (excluding China), and 51% in Latin America and the Caribbean. The corresponding figure of 33% for South Africa appears low by comparison (Vanek et al., Citation2014) and may be a result of the high degree of concentration and consolidation of the formal food economy (Greenberg, Citation2010; Greenberg, Citation2016).

In January–March 2017 some 2 681 000 people worked in a fluctuating informal sector; approximately 16.7% of total employment (Stats SA, Citation2017). Of this, trade constituted 41%. Thus, while the South African food system is characterised by a highly-concentrated core formal economy, it also comprises a large informal periphery constituting 32–45% of the food market (Greenberg, Citation2010; Greenberg, Citation2016).

The informal food economy is common in all African cities, with Crush & Frayne (Citation2011) considering this particularly important in cities such as Lusaka, Harare, Blantyre and Maputo. Similarly, within South Africa descriptions by Abrahams (Citation2006) of alternative food supply systems in Johannesburg reveal the ongoing use of informal vendors. Food vending is an important component of Cape Town townships with a high general occurrence (19.2 outlets per 1000 residents – collectively including liquor retailing, spaza [grocery] shops, house shops and takeaway trade) revealing highly entrenched local buying habits amongst township residents (Charman et al., Citation2017).

Skinner & Haysom (Citation2016), highlight how the informal food economy is also an important channel for food access for the food insecure where it reflects a core aspect of the foodways of South Africa’s poor (Kroll, Citation2016). This is reflected through the role of street foods in providing daily dietary intake (Steyn et al., Citation2013) but, in various cases (in Cape Town and Johannesburg) more frequently utilised than supermarket chains (Battersby, Citation2011; Rudolph et al., Citation2012).

Informal businesses offer affordable unit sizes, credit, long opening hours, convenient locations, daily re-stocking of fresh produce, fresh produce often cheaper than at supermarkets, and a range of meat cuts responding to cultural preferences and tastes. These are balanced by disadvantages such as higher unit costs, perceived lower quality, a limited range, lack of a cold chain, and perceived food safety risks. The informal food economy can appear to have a complementary and apparently symbiotic relationship with formal sector retailers (Peyton et al., Citation2015).

South Africa appears to be in a nutrition transition – a global trend towards greater consumption of energy-dense foods which is increasingly affecting developing countries of the global South. This transition is associated with the growing prevalence of various non-communicable diseases (Drewnowski & Popkin, Citation1997; Popkin, Citation2003; Drewnowski, Citation2004; Popkin, Citation2004).

The nutrition transition in southern Africa is driven by persistent poverty, and therefore reveals specific patterns. These include the simultaneous existence of macro-nutrient over-nutrition and micronutrient malnutrition, stubbornly high levels of early childhood stunting, particularly in poor urban areas, high and increasing prevalence of obesity, especially among women and in urban areas, a vicious cycle of food insecurity, malnutrition and HIV/AIDS, and negative impacts on mental and physiological health (Crush et al., Citation2011). Specific aspects of urban environments appear to promote these patterns in South African cities, although the concept of food deserts as developed in the global North is limited in its usefulness in the South African context (Battersby, Citation2012; Battersby & Crush, Citation2014; Kroll, Citation2016). This highlights the need to understand the role played by local food geographies, particularly in poor settlements, in mediating and influencing access to food.

Glanz et al. (Citation2005) present a conceptual framing of food environments. In this model, community nutrition environments reflect the neighbourhood scale, consumer food environments focus more closely on in-store features. To describe the community nutrition environment, Glanz et al. (Citation2005) consider the distribution of food outlets including the number, type, location, and accessibility, using geographic information systems, land-use and census data, food licence lists, and website searches. However, in considering food environments, it is also important to understand how research boundaries can take account of people’s mobility patterns, to consider how food environments change over time in response to seasonal and diurnal cycle, and to recognise how minority and vulnerable communities navigate and influence local food environments (Gittelsohn & Sharma, Citation2009).

A fundamental limitation of food geography models developed in the US and UK is that they emerged in a highly formalised context in which data sources are comprehensive, well-managed and accessible. The South African context is very different – limiting the usefulness of adopting the food environments frameworks of the global North. Challenges include the spatial and infrastructural legacies of apartheid planning and subsequent urban development policy, high levels of mobility and migration, and the key role played by informal economies closely enmeshed with highly consolidated formal food value chains (Kroll, Citation2016).

Therefore, in South African urban settings characterised by high degrees of informality and poverty, the prevalence, spatial distribution and type of foods accessible via informal trade are of particular interest in the study of community food environments.

Although the role of the informal food economy in local food environments and nutritional outcomes is important and still poorly-researched, as noted by Even-Zahav & Kelly (Citation2016), there is also a significant dearth of research concerning the subjective experiences, motivation and agency of informal food economy operators and clients. Initial research suggests that the lack of adequate storage and refrigeration leads to high rates of spoilage, raising questions around waste management in the informal sector.

Several questions emerge from this review, and the empirical data gathered in this study seek to shed light on these.

Firstly, what features of the ‘missing middle’, namely, food processing, distribution, and retail, can be discerned at the neighbourhood scale? Secondly, to what extent is the informal food economy of the survey areas enmeshed with the formal food economy, addressing the theoretical tension between structuralist and dualist frameworks? Thirdly, to what extent does the informal food economy present livelihood opportunities that could contribute to local economic development?

Fourth, to what extent do the findings of this survey validate the positions of legalist or voluntarist schools of thought on informal economies, that is, to what extent is government regulation perceived as onerous or enabling and how does this influence food entrepreneurs’ choices to operate informally? Fifth, what does the mapping of the informal food economy reveal about the local food environment and the extent to which it enables or constrains access to healthy or risky foods? Sixth, to what extent are informal food enterprises in the study area affected by challenging operational environments such as state harassment and lacking infrastructure? Finally, this study also considers why consumers frequent informal food sources.

Working towards filling knowledge gaps on these enterprises and their place in the broader township economy could enhance understanding of their contribution towards urban food security and provide evidence for bolstering of municipal and industry support, lifting food standards, enhancing supply chains and market efficiencies. As such, in a process towards building this knowledge base, we conducted a qualitative study into these microenterprises and a broader supply chain and consumer investigation of the township informal foodservice sector.

2.1. The study area

Cape Town is a coastal city of 3.74 million people (Statistics South Africa, Citation2011) with a historic city centre that sprawls eastwards onto a large sandy plain of working class ‘townships’ known as the Cape Flats. Cape Town’s population is racially and culturally diverse (McDonald, Citation2008), including 48% Coloured (commonly descended from Khoisan and mixed ethnic influences), 32% Black (primarily isiXhosa-speaking), and 18% White South Africans (City of Cape Town, Citation2009). Cape Town is a fast growing centre with an estimated in-migration of 13 000 persons per month (Poswa & Levy, Citation2006). Such economic migrants largely comprise isiXhosa rural persons originating from the Eastern Cape Province with the great majority establishing themselves within the 232 informal settlements scattered across the city (City of Cape Town, Citation2010). Of Cape Town’s collective 1 068 000 households, 22% are economically indigent, of which over half reside in untitled informal dwellings (City of Cape Town, Citation2007). Formal unemployment in the city is 23.8% (StatsSA, Citation2011), although locally it exceeds 60% in socio-economically challenged township settlements of the city (DSD, Citation2007) such as across the Cape Flats. It is within these communities that informal foodservice predominates, and where the study was undertaken.

3. Methodology

The study methodology adopted a mixed-methods approach which involved multiple phases. Firstly, a microenterprise database comprising findings of small-area censuses conducted by the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation (over the course of 2010–14) in five Cape Town townships was interrogated. A total of 588 informal food retail and related businesses from the ∼3800 microenterprises identified in the townships of Philippi, Sweet Home Farm, Delft South, Vrygrond and Imizamo Yethu was identified. Analysis of the qualitative data associated with these enterprises was conducted and included:

Business type

Business location (using GPS positioning)

Owner demography

Enterprise turnover

Retail prices of traded products

Reviewing photographic images of businesses, menus and other relevant features.

Secondly, a process of primary research was undertaken by revisiting 50 of these informal foodservice microenterprises located in Philippi, Delft South and Sweet Home Farm from May to August 2014 and conducting 40 minute semi-structured interviews with each. Questions on predetermined topics such as household structure, income streams, products, prices, volumes traded, local business environment, and opportunities and threats to business were discussed. The researchers spent up to four hours in each business outlet observing operations and customer behaviour. Building on participant responses, supply chain mapping of raw ingredients and inputs (such as cooking fuel, utensils and transport) was undertaken. It must be emphatically stated that the information thus recorded reflects primarily the foodservice operators’ subjective perceptions and understanding of their business’ upstream supply chains. For each step in the supply chain participant perceptions of major business influences, including other chain participants, support industries such as transport, and the broader environment including policy, infrastructure, institutions and processes that influence the market were gleaned. Three local government officials, two wholesale suppliers of food inputs and an informal transport supplier were also interviewed.

Thirdly, we conducted a 75 person consumer study with persons utilising these enterprises using an open-ended questionnaire tool. Each interviewee was approached after their visit to an informal foodservice vendor within the various research sites. After consent was obtained, the consumer survey occurred as a rapid assessment over 15 minutes, exploring participant demographics, socio-economics, and qualitative understanding of the nature of demand for informal foodservice. Consumers were asked about their foodservice eating choices and preferences, and a range of questions pertaining to their patronage of formal and/or informal businesses.

Participant insights were gained through open-ended questions and informal discussion – in essence ‘conversations with purpose’ (Drury et al., Citation2011, 257) – allowing the researchers to inquire without unintended influence, iteratively creating opportunity for broader discussion to emerge. Broad ranging conversations with all stakeholders also revealed commodity chain dynamics that formed the enabling business environment, and other factors not easily known beforehand. To enhance participant comfort and ensure correct interpretations of responses, a culturally representative and multilingual investigatory team with practical understanding of informal enterprise operations was trained by the lead researcher and participated in field research. All data were anonymised.

Finally, all microenterprise and consumer survey findings were recorded in Microsoft Excel, examined for commonalities and frequencies, and reviewed. The data allowed the researcher to map commodity flows from raw ingredient procurement through the processing and eventual retailing stages to the end-consumer.

4. Results

4.1. Informal microenterprise census and township business landscape

The informal microenterprise census (Charman et al., Citation2017) revealed that six prominent business types in the Cape Town residential township setting are (in declining order) liquor retailers (shebeens), spaza shops (specifically defined as having independent business premises, a dedicated product fridge and at least eight of 10 staple food products), house shops (individuals working from private homes and selling a basic range of items such as chips, sweets and paraffin), hair salons/barber shops, informal foodservice (such as fast food takeaways in the form of street braai – BBQ) and mechanical/electrical repairs. Four of these six enterprise types are involved in food or drink retail – implying the high importance of food as a part of business activity.

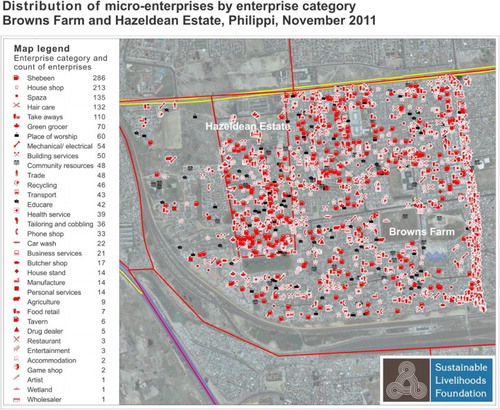

A map of Philippi Township reveals the extent of informal micro-entrepreneurship in the local area, including predominant business types ().

Within the database a number of microenterprise types were identified as relevant to informal foodservice. These were grouped into two business categories which were broadly defined by their positioning in the supply chain. These categories are:

Actual informal foodservice businesses that primarily retail cooked food – chicken, sausages and other meat types. Broadly speaking, this category includes business enterprises such as street barbeques, takeaways and meal preparers.

Enterprises that potentially supply informal foodservice enterprises with inputs such as raw meat, cooking oil or wood. These include butcheries or street side meat sales, and also local transport businesses that ferry these inputs.

It is important to note that the retail supplier type business such as spaza shops and street traders were not all necessarily suppliers to informal foodservice enterprises. However, they remain relevant in the broad understanding of the informal foodservice economy.

Whilst not all respondents in the informal microenterprise census were asked for nationality, of those businesses that prepare and sell cooked food, the great majority are owned by South Africans (87%). Only four other nationalities were represented, with Zimbabweans being the largest.

For the 402 informal foodservice enterprises in the microenterprise small-area census database, 224 reported on the structure of their enterprise with nearly three quarters of these operating as prepared food takeaways in temporary structures (including tents, tables, braais, and self-built units). The remainder worked from private homes. The businesses were revealed to be largely scattered throughout the residential township environment.

4.2. Microenterprise interviews – general business dynamics

Guided by the findings of the database, the predominant business types of the 47 interviewed in the subsequent informal foodservice sample were takeaways (37/79%) (either BBQ or deep fried products) where prepared food served from the premises is predominately taken off-site to be consumed elsewhere by the customer. The remaining were restaurant-styled enterprises – specialising in sit-down meals () ().

Table 1. Interview sample and enterprise type.

Across the range of interviewed informal foodservice microenterprises sustainability appears high with the average length of time in business reported in interviews being 4.2 years – the oldest establishment operating for 16 years, and the youngest for three months. Yet despite the general business age, growth appears limited. With respect to employment most of these enterprises are worthy of their generally ‘micro’ status, with only two enterprises employing staff outside of direct family members (respectively six, and three employees). The majority of the enterprises were not sole operators, with many relying on family involvement as a key strategy within their enterprises, with assistance commonly rendered by wives, husbands and children – primarily in food preparation. This implies that Neves & du Toit’s (Citation2012) assertions of reliance and transfers between the domestic and enterprise economy are critical in informal foodservice microenterprise operations.

The township informal foodservice sector is predominated by the trade in cooked meat products – the primary business of all the enterprises sampled. For all of the enterprises surveyed the primary products traded are cooked chicken pieces, including chicken feet (32%), although most traders prepare a range of products including ‘Russians’, polonies, pork and boerewors (49%). Others prepare items such as vetkoeks (deep fried dough cakes), deep fried potato chips and cooked snack foods ().

Plate 2. Braaied (BBQ) chicken feet (R0.50 per foot) served in scrap paper wrapping from a street barbeque; Delft Cape Town.

According to the responses of business owners, the operating hours in the informal foodservice sector show considerable individuality. Business hours tend to vary according to enterprise, meal types prepared and served, enterprise location, and are largely influenced by the specific days of the week. For example, many of the businesses indicated different operational hours during the week and the weekend. Weekend hours are generally considerably longer – indicating improved sales over this period. Many enterprises reported opening hours to be coinciding with shebeen operations where they capitalise on such customers.

As a general trend, reported primary operating times for informal foodservice enterprises consist of:

30% operate in the morning

28% operate in the afternoon

28% operate in the evening

8% operate late into the night

Whilst some of these enterprises were open across two or more of these periods, the majority of businesses appear to specialise their operations during certain time windows, with the majority of smaller enterprises concentrating their work activities and trade from Thursdays to Sundays, midday to evening.

The most common equipment owned by the respondents were deep fryers (34%), braais (30%), and freezers (17%) (). Many business owners had only one of these items, and none owned all of these items. Of the interviewed businesses, 4% owned none of those appliances, and were primarily cooking on household kitchen stovetops.

Table 2. Business assets held by informal foodservice enterprises.

Access to a motor vehicle was also limited amongst the interview sample with 13% of the businesses reporting owning (2), hiring, or borrowing a car from a neighbour or family member. The great majority (87%) of respondents indicated they had no private vehicle access and were reliant on various transport modes including minibus and amaphela (sedan) taxis, bicycles, collecting goods in trolleys and walking to their suppliers. Despite what appears to be a considerable logistic challenge, microenterprises conducted stock purchases approximately three times per week, with some purchasing daily. The average amount of money spent on a stock purchase is R1,214 while the median is R717. Distance to wholesalers and available storage space (such as refrigerators) were commonly cited as limiting factors in the quantities of stock purchased. None of the respondents indicated that goods are delivered to their businesses by their suppliers, which implies their micro-status gives them limited leverage in their supplier relationships, reinforcing the critical influence of close proximity for such suppliers.

Demand for informal foodservice is considerable. Amongst readily comparable meat braaiers (the predominant study group) the average reported number of customers per week was calculated as 247. Note that reported customer numbers are influenced by the amount of time a business spends operating which varies from enterprise to enterprise, and also the type of products traded. For example, commonly interviewed chicken feet braaiers who trade a low-priced snack consistently report trading with the highest numbers of customers and likely raise the general average. Purchase amounts spent per customer visit range from as much R70 per plate for a pre-prepared meal, to as little as R0.50 (for one street-braaied chicken foot). The average spend is R24 per visit, although for those visiting street BBQ or takeaways, this falls to an average of R15.90 per trade (the average spend being lowered through the cheaply obtained and popular braaied chicken feet).

Building upon data from 106 respondents in the prior small area census findings, and the primary research in this case, enterprise turnover and profitability was estimated. Each of the 47 business owners interviewed was asked to supply profit per day, week and month ().

Table 3. Reported profits per day, week and month for township foodservice.

It is hypothesised here that the figure reported daily is the most representative figure of business profit. This is because many business enterprises are not operated on a full time basis, opening at more lucrative operating days and times – most commonly evenings from Thursday to Sunday. These data should be interpreted with some caution and should not be used to characterise the entire township retail foodservice sector, firstly as the enterprises represented in this analysis are biased towards street braai trade as the most prominent township foodservice enterprises, with these having the least business investments. Secondly, through broader understanding of the informal context it has become apparent that cash profits are not necessarily a universal determining factor behind the existence of survivalist enterprises (in this respect see Neves & du Toit, Citation2008). For example, a woman who operates an informal foodservice enterprise from home is likely able to simultaneously care for her children or run other business enterprises. Furthermore, the enterprises are cash-based and the income has no bearing on social grants or other income streams within the household.

Of the specific study group sample, 70% of enterprises reported that the informal foodservice business was the primary source of income to the operator’s household. Where this was not the case, other income sources included child grants, pensions, other informal businesses such as taverns or car washes, and two cases of formal sector jobs – with the municipality and the South African Navy.

4.3. Informal foodservice supply chains

Interviews with foodservice operators highlighted a relatively short supply chain generally extending from formal economy wholesalers (selling commercially grown produce) via informal foodservice operators to consumption. It is important to note here that this reflects the perceptions of the interview respondents, the majority of whom were foodservice operators. Only a small number of upstream suppliers were interviewed, and more primary research is needed to understand upstream value chains. Each link in the chain and their respective activities and value adding is summarised below.

4.3.1. Formal economy wholesalers

Formal economy wholesalers in this study were located at the geographic fringes of the township setting, easily reached through public transport. They mostly consist of butchery related enterprises that specialise in wholesaling bulk quantities of budget meat cuts including cow/pig/chicken offal, feet, and heads which are sourced from commercial abattoirs and importers. Items such as heads are sold loose from open freezers, with chicken feet ordered over a counter, then shovelled from pallets into reinforced plastic bags and sold by the kilogram. Butchery wholesalers and other more generalist wholesale outlets also trade spices, sauces and other cooking materials in bulk quantities. These shops are open for long hours, with customers arriving on foot, in public transport or in private vehicles. These wholesalers are characterised by long queues, high security and predominately cash trade. Their comparative advantage is the ability to trade in large volumes at low margins with their economies of scale unachievable by any of the informal foodservice enterprises encountered.

4.3.2. Informal economy transport providers

In visiting the above wholesalers, minibus taxis and amaphelas (hired private taxi sedans) are important transport providers. Minibus taxis generally collect and drop-off informal foodservice operators between home (business) and wholesalers, charging them on an estimated volume basis for additional room taken up in the vehicle by their purchases. More commonly, business owners utilise amaphelas that provide transport for the entire provisioning process. This service is considered highly valued and efficient, with a set fee (around R70 for a complete journey – although influenced by place, time and distance) which can also include driver waiting time (during the shopping process), and in some cases assistance packing and emptying stock from vehicles.

4.3.3. Informal economy provisioners

Spaza shops, street traders and other enterprises support informal foodservice by supplying items such as bread, sauces, salt and cooking oil. Interestingly, foodservice operators commonly claimed they would not procure chilled or frozen meat supplies from the township spaza sector. This was due to perceptions of poor meat quality and lack of cleanliness. Some meat trading enterprises exist in the township setting, such as traders marketing commercially exhausted battery chickens. These are live traded at R50–70 each (commonly with a R10 margin per bird above the farmer price) and slaughtered/processed in private homes. Live birds were said to fulfil the cultural preferences for ‘gamier’ meat ().

4.3.4. Informal economy fuel providers

The vast majority of enterprises cook their ingredients on open fires. There are notable fuel shortages and complaints about poor quality and recycled fuelwood. The use of industrial pallet timber (purchased expressly for cooking with at R1 per pallet) and exotic alien timber (such as Acacia spp.) is commonplace. A trolley load of such timber can cost R20–40 depending on volume, timber type and wood piece sizes.

4.3.5. Landlords (including services provision)

Informal foodservices trading from public pavements commonly hire electricity via extension leads from adjacent properties. Electricity can cost R50 per week or more depending on frequency of use, access reliability, and scale of illegality of the connection. Water is commonly purchased and fetched from these neighbours in buckets.

4.4. Operational environment

Participants were questioned on matters pertaining to relevant South African government service delivery, including access to trading sites, electricity, water, permitting and law enforcement. The majority of microenterprises interviewed revealed a lack of interaction between themselves and relevant government authorities (46 of the 47 enterprises claimed very little or no interaction with municipal officials). This finding could be interpreted as positive for entrepreneurship activity – revealing how limited state interference has potentially allowed for much microenterprise activity within the informal township context. Despite the claimed limited interaction, a local municipality presence was noted throughout all sites with law enforcement, refuse collection and local health care services observed. One of the critical business environment themes that emerged was the lack of security for the informal business sector in townships. Almost all the respondents had either themselves, or had witnessed neighbouring enterprises being robbed through criminal activity.

Local government officials noted the key challenges of permitting for informal operations. This primarily relates to aspects of food safety and trading locations. It was highlighted that individual traders commonly failed to comply with locally set food safety requirements with respect to commercial food standard kitchens or operating premises. Despite these local government concerns, most informal foodservice operators operated outside of regularised trading areas (such as informal settlements and from their homes) and therefore the scrutiny of law enforcement officials.

Operators tended to be upbeat about the potential in their business as a response to enhanced investment into the broader business environment. Those operating on the street pavement highlighted the value of trading shelters so that they would be able to operate in all weather conditions. Other than shelter, various individuals highlighted the value of basic services such as water and electricity within their businesses to cut the cost of renting and time spent moving to access them. Many were hopeful of being able to rent trading sites directly from the municipality to remove themselves from the influence of private landlords, some of whom were claimed to be unscrupulous. Some claimed to be willing to pay for legal opportunities to trade from designated spaces.

4.5. Consumer feedback

A random survey of 75 consumers across age (15–60 years), gender (38M/37F) and ethnicity (black/coloured) who purchase from township-based informal foodservice enterprises was conducted. It emerged that consuming from informal foodservices is a commonplace activity. Street food was commonly considered ‘tasty’ across all demographic groups, with a further reason for female patronage in reducing domestic workload. This finding was reflected by more women consuming their purchases at home compared to men who tend to eat at the point of purchase ().

Table 4. Where do you eat food bought from township foodservice? (N = 75).

Both males and females expressed unwillingness to cook as a reason why they buy prepared street food. Women also viewed informal foodservice as cheaper than buying from formal shops (). A common female perspective was that if one is financially broke, you can always find enough money to purchase (for example) cooked chicken feet in the township – a product largely unavailable in formal outlets.

Table 5. Reasons behind purchase decisions from township foodservice (N = 75).

Informal foodservice is a well utilised business service in the township context. Male informal foodservice consumers spend a surprisingly high average of R218.26/week/person on informal foodservice; amounting to R31.15 per day (potentially split across numerous purchases). Women spend considerably less than their male counterparts; an average R93.65 per week, or R13.38 per day. In the predominant research site of Philippi, 78% of households have an income of R3,200 per month or less (City of Cape Town, Citation2013). What appears to be a substantive level of spending reflects the importance of informal foodservice as part of daily life of township residents, and the likely strategic role of the business in serving commuter markets. The considerable demand for street food by the resident community implies its important role and abundance of microenterprises in the township context.

5. Discussion

Informal foodservice is a highly utilised business and plays an important role in meeting daily food demands for township residents. The research process revealed a number of categories of informal economy food retail enterprises – such as street-based barbeque, deep fried takeaway outlets and sit-down ‘restaurant’ shisanyama venues. Foods prepared and traded from these outlets are geared to local consumer budgets (including cheap cuts of meat), cultural preferences (including meal types and service) in contemporary township society with many of these consumer demands not being directly met within the formal economy. Similar to the traditional medicine economy findings of Trienekens (Citation2011), the township foodservice industry effectively forms a distinct food retailing informal economy suited to local circumstances outside of formal and regulatory frameworks.

What then are the implications of this study’s findings for the theoretical questions outlined earlier? The first question concerned the ‘missing middle’ of the food economy in the areas surveyed. This study showed that, whilst embedded into informality, township foodservice is highly reliant on inputs emerging from formal sector enterprises in the form of agricultural producers, wholesalers, and retailers. Supply chains in the sector are relatively short. All microenterprises in the study source their main food inputs from formal economy businesses (wholesalers) who in turn buy directly from abattoirs and importers. The sector also provides income opportunities for related informal enterprises including minibus and sedan taxis, street sales of bread, firewood and live chickens. Most microenterprises conduct the activities of stock and input procurement, food preparation and retailing themselves from within the township environment and adjacent formal sector wholesalers. The informal economy linkages are however quite apparent, with suppliers providing cultural niche items such as live chickens (spent hens), vegetables, transportation, electricity (access hire), water and real estate provision, labour, and occasional items such as condiments and firewood. Interestingly the forms of many of the food items traded would be of limited value to formal markets.

This finding also has implications for the second theoretical question concerning linkages to the formal economy: the majority of produce traded in the study areas was sourced from formal-sector suppliers who capitalised on their location in close proximity to these settlements. Whilst quantities were not directly tracked in this study it is apparent that unprocessed fifth quarter products (including visceral fat, alimentary tract, visceral organs, feet and heads – Helou, Citation2004) make up a considerable proportion of traded products. In this way the informal economy potentially creates an important efficiency for markets through full ‘nose to tail’ utilisation of animal products. In this way the informal economy potentially serves a useful role in externalising formal sector costs of disposing of fifth quarter products and therefore enhancing overall market efficiencies. However, the study also found that informal foodservice relied on local informal spaza shops to access produce, implying dense local value chain networks. This highlights that informal foodservice in this setting is in fact densely networked with both formal and informal upstream value chains and that the dualist position is not supported by these findings.

The third theoretical question emerging from the literature review was to what extent the informal economy and especially foodservice represented opportunities for economic development and upliftment. The findings of this study suggest that the potentials are limited due to the reliance on short supply chains linking to the same wholesale operators, due to limited product or business diversification, due to the avoidance of direct competition, due to a high degree of business individualisation and due to the narrow margins possible in a generally impoverished consumer environment. These findings also suggest that it is problematic to consider the informal food economy purely from an entrepreneurship lens focused on business growth and capital accumulation, but that it is also a response to conditions of persistent poverty and disadvantage. The business is commonly geared to operate at peak times of trade such as commuting periods, allowing for the high participation rates of women (especially those with dependent children) who can adjust opening hours to suit other lifestyle considerations and responsibilities. Such businesses share compatibility with the arrangements discussed by du Toit & Neves (Citation2008) that help the poor survive as a form of social protection with such businesses being income producing, household food provisioning and accommodating of household labour requirements. Reflecting this social dynamic, simple commodity chains and limited value adding, average microenterprise profitability is a generally modest although likely a pragmatic activity in otherwise potentially limiting economic circumstances. These enterprises are also suited to lifestyle factors with the majority of township enterprises only trading at times of highest consumer demand and tend to close outside these periods.

Considerable reliance on highly proximate local markets potentially limits entrepreneurial growth prospects which may in turn influence how competition is collectively managed in the sector. Direct competitiveness appears to be intentionally avoided including common strategies of not trading in products being traded by one’s neighbours (Petersen & Charman, Citation2008; Neves & du Toit, Citation2012) practically meaning that liquor retailing shebeens generally do not sell food, and food retailers similarly rarely retail liquor. Larger business enterprises tend to also differentiate from one another through potentially diverse menu offerings, ‘special sauces’ and spices, strong product branding, emphasis on fresh produce, and through longer trading hours including operating late into the night.

Importantly, operating in such localities gives potential for individuals and their microenterprises to enter economic markets, meaning that a lack of infrastructure (e.g. not having a food grade kitchen, or a cool room), legality issues (such as lack of permits, certificates), or even a lack of menu offerings or facilities, or even a lack of individual entrepreneurial zeal does not prevent new foodservice enterprises from emerging. Indeed there can be benefits to this informality; for example the emphasis on cash trade effectively avoids much of the bureaucracy of business registration, accounts and taxation and minimises the capital outlay required to commence operations.

Yet, despite the popular nature of working in the sector any enhancement of individual incomes in the informal foodservice sector may pose challenges for development practitioners. Tschumi & Hagan (Citation2008) highlight that an important strategy can be through enhancing product credence (such as labelling, branding or certification) to create a consumer price premium. However in township markets served by many independent informal foodservice providers, consumer households might not be prepared to pay premiums for differently variated products when cheaper, similar alternatives are known to exist. As all enterprises were found to be very much independent from one another and self-reliant, it seems unlikely that collective groups of these independent foodservice operators will agree to coordinated price rising in this economy in order to raise collective profits. With respect to enhancing enterprise profitability through somehow further cutting business expenditure (if this is indeed possible), the ongoing business culture of microenterprise individualism raises individual costs as most foodservice participants conduct all commodity chain functions themselves, which limits the possibilities for gaining economies of scale.

Encouraging appropriate business development adjacent to township residential areas that could service such enterprises – ironically, potentially the expansion of supermarkets into these areas (Crush & Frayne, Citation2011) – may enhance local informal foodservice access to stock. Similarly, stockpiling fuelwood from government exotic tree clearing programmes into depots near the township could produce a cheap and local source of high quality firewood for cooking.

Further challenges include the informal and micro-status of these enterprises, the commonly extra-legal or illegal nature of operations (based on land-use zoning, informal status, and municipal permitting such as requiring food-grade kitchen permits), and the power imbalance they face with their formal sector suppliers creating difficulties for state or private sector interventions. In order to support the growth and activities of the sector it is likely that interventions will need to focus on aspects beyond the microenterprises themselves, such as the township business environment.

This is relevant to the fourth theoretical question arising from the literature review, which considered to what extent the regulatory business environment encourages or hinders formalisation. The vast majority of traders interviewed reported little if any interaction with government officials despite visible state presence. Although officials reported difficulties in enforcing compliance with regulations, the majority of traders did not feel that their businesses were at risk due to lacking trading permits even though they operated outside of demarcated trading areas. In this case neither the legalist nor the voluntarist perspectives are adequate in explaining the prevalence of the informal food economy in these study sites. Instead, in this case the state appears to engage in a form of benevolent neglect, while informal operators continue to trade in blithe contravention of existing regulations either through mutual acceptance, or simply a lack of enforcement of regulations. Further research is required to understand this conundrum around the governance of the informal food economy in African cities.

However, in order to support the business environment it is important for local economic development practitioners and officials to interpret informal foodservice as the grass roots of economic self-reliance and entrepreneurship. As informal foodservice microenterprises organically emerge to serve customer demand, within reason such microenterprises should be accepted, and even encouraged in non-traditional business locations – such as township residential areas. Allowing for this requires increasingly amenable town planning considerations and a reconsideration of by-laws that govern food preparation, trading activities and locations.

The fifth question related to the role of informal trade in facilitating food access, considering how the informal food trade shapes local food geographies and thus influences nutritional and health outcomes. From a geographical perspective, it is evident that foodservice outlets are densely clustered around major transit routes, emphasising the dependence on high volumes of passing trade. Conversely, due to the comparative scarcity of such outlets in more peripheral or deeply residential areas, these access benefits may not extend to the elderly, disabled or unemployed who lack the means to purchase from informal foodservice. In terms of the kinds of food retailed at these outlets, these were dominated by various forms of cooked meat, mainly chicken, as well as processed meats like polony and russians, pork and boerewors, much of this flame-grilled or deep-fried. Also prevalent was the sale of vetkoek (deep-fried dumplings). While chicken may be nutritionally valuable in terms of its protein content, the fact that it is often deep-fried, and the common retailing of other deep-fried and ultra-processed foods alongside foods extremely high in carbohydrates (e.g. pap, fried chips, vetkoek) suggests that, even though it is providing convenient access to food for many, the informal foodservice economy is also likely contributing to obesogenic food environments due to the energy-dense nutritional profile of these foods (see Feeley et al., Citation2009 ).

Relevant insights also emerge concerning the sixth theoretical question, which considers traders’ subjective experiences of the trading environment. This study confirms the general lack of appropriate infrastructure documented by other studies (Mkhize et al., Citation2013; Kroll, Citation2016; Battersby & Marshak, Citation2017), including access to water, electricity, and shelter. This contributes to a very challenging operating environment for informal foodservice enterprises. Enhancing infrastructure and utility provision in the residential township environment would go some way towards promoting microenterprise success. Improved street lighting would enhance client safety, and operating hours. Increasing accessibility of water and electricity to traders would improve facility cleanliness and support increased efficiencies to their enterprises.

6. Conclusions

This study was able to contribute to the body of knowledge supporting the debate around several questions of broader relevance to the understanding of the informal economy in general, and the informal food economy in particular. These can inform a range of interventions with potential for implementation by policy makers to support the sector. Interventions must focus on bolstering the broader business environment and need to be considered within the context of the informal economy, localised consumer demand and existing cultural frameworks. While they should explicitly take into account the role of the informal foodservice sector in contributing to livelihoods and food security for the poor, such interventions should also consider how the sector may be shaping food environments that reinforce the nutrition transition and swell the rising tide of non-communicable illness. It is therefore essential that interventions aimed at the informal food sector also be designed to promote food sourcing and preparation practices that reduce health risks and facilitate access to health-promoting foods.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abrahams CN, 2006. Globally useful conceptions of alternative food networks in the developing south: The case of Johannesburg’s urban food supply system. Online papers archived by the Institute of Geography, School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh.

- Battersby, J, 2011. The state of urban food insecurity in Cape Town. Urban Food Security Series No. 11. Queen’s University and AFSUN, Kingston and Cape Town.

- Battersby, J, 2012. Beyond the food desert: Finding ways to speak about urban food security in South Africa. Human Geography 94(2), 141–59.

- Battersby, J & Crush, J, 2014. Africa’s urban food deserts. Urban Forum 25(2), 143–51. doi: 10.1007/s12132-014-9225-5

- Battersby, J & Marshak, M, 2017. Mapping the invisible: The informal food economy of Cape Town, South Africa. Southern African Migration Programme.

- Battersby, J, Marshak, M & Mngqibisa, 2016. Mapping the invisible: The informal food economy of Cape Town, South Africa. AFSUN Urban Food Security Series Nr 24.

- Charman, AJ, Petersen, LM, Piper, LE, Liedeman, R & Legg, T, 2017. Small area census approach to measure the township informal economy in South Africa. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 11(1), 36–58. doi: 10.1177/1558689815572024

- Chen, MA, 2012. The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. WIEGO Working Paper Nr1.

- City of Cape Town, 2009. “State of Cape Town 2008: Development issues in Cape Town.”

- City of Cape Town, 2007, 2010. General statistical data for City of Cape Town as compiled by the Strategic Information Department. http://www.capetown.gov.za/en/stats/Documents/City%20Statistics%202009.htm Accessed 2 February 2016.

- City of Cape Town, July 2013, 2011. Census suburb Philippi. Compiled by Strategic Development Information and GIS Department (SDI&GIS), City of Cape Town 2011 Census data supplied by Statistics South Africa.

- Cohen MJ & Garret JL, 2009. The food price crisis and urban food (in)security. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Human settlements working paper series; Urbanisation and emerging population issues – 2.

- Crush, J & Frayne, B, 2011. Supermarket expansion and the informal food economy in Southern African cities: Implications for urban food security. Journal of Southern African Studies 37(4), 781–807. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2011.617532

- Crush, J, Frayne, B & McLachlan, M, 2011. Rapid urbanization and the nutrition transition in Southern Africa. AFSUN Series 7. AFSUN, Cape Town.

- Devey, R, Skinner, C & Valodia, I, 2003. Informal economy employment data in South Africa: A critical analysis. Paper presented at the TIPS AND DPRU FORUM 2003, The Challenge of Growth and Poverty: The South African Economy Since Democracy, 8–10 September 2003, Indaba Hotel, Johannesburg

- Drewnowski, A. 2004. Obesity and the food environment: Dietary energy density and diet costs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 27(3), 154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.011

- Drewnowski, A & Popkin, BM, 1997. The nutrition transition: New trends in the global diet. Nutrition Reviews 55(2), 31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x

- Drury, R, Homewood, K & Randall, S, 2011. Less is more: The potential of qualitative approaches in conservation research. Animal Conservation 14, 18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00375.x

- DSD, 2007. Khayelitsha - Livelihood profile of Khayelitsha and situational analysis of DSD services in the node Department of Social Development Pretoria, South African National Government.

- Du Toit, A & Neves, D, 2008. Informal social protection in post-apartheid migrant networks: Vulnerability, social networks and reciprocal exchange in the Eastern and Western Cape, South Africa. Brook’s World Poverty Institute Working Paper 74. Manchester: Brook’s World Poverty Institute, University of Manchester.

- Du Toit, A & Neves, D, 2014. The government of poverty and the arts of survival: Mobile and recombinant strategies at the margins of the South African economy. Journal of Peasant Studies 41(5), 833–53. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2014.894910

- Even-Zahav, E & Kelly, C, 2016. Systematic review of the literature on ‘informal economy’ and ‘food security’: South Africa, 2009–2014, Working Paper 35. Cape Town: PLAAS, UWC and Centre of Excellence on Food Security.

- Feeley, A, Petifor, JM & Norris, SA, 2009. Fast-food consumption among 17-year-olds in the birth to twenty cohort. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2(3), 118–23. doi: 10.1080/16070658.2009.11734232

- Gittelsohn, J & Sharma, S. 2009. Physical, consumer, and social aspects of measuring the food environment among diverse low-income populations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(4S): 161–5.

- Glanz, K, Sallis, J, Saelens, B, & Frank, L. 2005. Healthy nutrition environments: Concepts and measures. American Journal of Health Promotion 19(5): 330–3. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330

- Greenberg, S, 2010. Contesting the food system in South Africa: Issues and opportunities. Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape.

- Greenberg, S, 2016. Corporate power in the agro-food system and South Africa’s consumer food environment. PLAAS Working Paper 32. PLAAS, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town.

- Hart, K, 1973. Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies 11(1), 61–89. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X00008089

- Helou, A, 2004. The fifth quarter: An offal cookbook. Absolute.

- Kroll, F. 2016. Foodways of the poor in South Africa: How value-chain consolidation, poverty and cultures of consumption feed each other, Working Paper 36. PLAAS, UWC and Centre of Excellence on Food Security, Cape Town.

- McDonald, DA. 2008. World city syndrome: Neoliberalism and inequality in Cape Town. Routledge, 355.

- Mkhize, S, Dube, G & Skinner, C. 2013. Informal economy monitoring study: Street vendors in Durban, South Africa. WIEGO, Manchester, UK.

- Moser, CN, 1978. Informal sector or petty commodity production: Dualism or independence in urban development. World Development 6.

- Neves, D & Du Toit, A, 2008. The dynamics of household formation and composition in the rural Eastern Cape. Centre for Social Science Research.

- Neves, D & du Toit, A, 2012. Money and sociality in South Africa's informal economy. Africa 82(1), 131–49.

- Petersen, L & Charman, A, 2008. Making markets work for the poor – understanding the informal economy in Limpopo. Report for the Limpopo Centre for Local Economic Development, commissioned by Sustainable Livelihood Consultants and Cardno Agrisystems, Cape Town.

- Peyton, S, Moseley, W & Battersby, J, 2015. Implications of supermarket expansion on urban food security in Cape Town, South Africa. African Geographical Review 34(1), 36–54. doi: 10.1080/19376812.2014.1003307

- Popkin, BM, 2003. The nutrition transition in the developing world. Development Policy Review 21(5–6), 581–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8659.2003.00225.x

- Popkin, BM, 2004. The nutrition transition: An overview of world patterns of change. Nutrition Reviews 62(7 pt 2), S140–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00084.x

- Poswa, N & Levy, R, 2006. Migration study in Monwabisi Park (Endlovini), Khayelitsha Strategic Information Branch. Cape Town, City of Cape Town.

- Rudolph, M, Kroll, F, Ruysenaar, S & Dlamini, T. 2012. The state of food security in Johannesburg. Urban Food Security Series No. 12. Queen’s University and AFSUN: Kingston and Cape Town.

- Skinner, C & Haysom, G, 2016. The informal sector’s role in food security: A missing link in policy debates? Working Paper 44. Cape Town: PLAAS, UWC and Centre of Excellence on Food Security.

- Statistics South Africa, 2011. South African census 2011, Government of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Statistics South Africa, 2017. Quarterly labour force survey Quarter 1:2017. Statistical release P0211.

- Steyn, N, Mchiza, Z, Hill, J. et al. 2013. Nutritional contribution of street foods to the diet of people in developing countries: A systematic review. Public Health Nutrition 17(06), 1363–74. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013001158

- Trienekens, JH, 2011. Agricultural value chains in developing countries - A framework for analysis. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 14(2), 51–83.

- Tschumi, P & Hagan, H, 2008. A synthesis of the making markets work for the poor (M4P) approach. UK Department for International Development (DFID) and Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC).

- Vanek, J, Chen, MA, Carré, F, Heintz, J & Hussmanns, R, 2014. Statistics on the informal economy: Definitions, regional estimates & challenges. WIEGO Working Paper Nr2.

- Williams, C, Martinez-Perez, A & Kedir, AM, 2016. Entrepreneurship in developing economies: The impacts of starting Up unregistered on firm performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice.