ABSTRACT

This paper suggests that sufficient imagination about the role of the university as a place-based actor, in conjunction with conditions of institutional embeddedness and normative alignment of university-community engagement, are minimum requirements for place-specific engagement. To explore this process of alignment and institutional conditions in practice, this paper explores one university's approach to embedding engagement and its sense of place-making in the context of multiple institutional logics. Findings show how the university has attempted to embed engagement by following a protracted consultative process that enabled engagement to be aligned with and integrated into the core functions of the university. Findings also show that engagement continues to be driven, at least partially, by market logics that favour financial imperatives over those of place-making.

1. Introduction

According to Perry and Villamizar-Duarte (Citationforthcoming), ‘universities as place-based or “urban” anchor institutions have the capacity to fly in the face of increasing hegemonic, individual and entrepreneurial logic(s)’. In this paper, we argue that in order for universities to deploy their capacity fully so that they can be anchored in place, and displace self-seeking and entrepreneurial logics, a process of institutional change must take place. To be specific, the delegitimisation of one form of university-community engagement that values exchange with external communities for the financial benefit of the university (and is tenuously linked to the core functions of the university) and the institutionalisation of a form of university-community engagement that values place-specific development (while simultaneously strengthening teaching and research) needs to take place.

Boyer (Citation1996), Muller (Citation2010) and Watson et al. (Citation2011) all stress the historical dimension of engagement – how dominant social issues have determined the form of interaction between the university and society. The contemporary university is under growing pressure to illustrate the impact of the knowledge it produces. Under the watchful gaze of their benefactor governments and expectant publics, universities are expected to balance social relevance with the rigours of a competitive global higher education environment. Universities, as organisations with embedded and resilient institutional norms values, may adapt several strategies in dealing with external pressures to be more responsive (Oliver, Citation1991; Scott, Citation2014). University-community engagement is one such response, and there is evidence of its increasing legitimisation and diffusion as evidenced by the establishment of university centres, units and committees to manage and coordinate engagement, the founding of global networks of engaged universities such as the Talloires Network, and the publication of academic journals to promote university-community engagement as a field of study, to name a few (Hall et al., Citation2015).

Scott (Citation2014:169) points to the fragmentation on normative consensus within institutions as social pressures mount: ‘the presence of multiple competing and overlapping institutional frameworks undermines the stability of each’. Thornton et al. (Citation2012), acknowledging the agency of institutionally-bound actors and the effects of multiple competing frameworks, propose the notion of ‘institutional logics’, that is, ideal-type logics – potentially in conflict – that serve as multiple sanctioned scripts for action. They propose seven societal-level logics: family, community, religion, state, market, corporation and profession. According to Scott (Citation2014:91): ‘Many of the most important tensions and change dynamics observed in contemporary organizations and organization fields can be fruitfully examined by considering the competition and struggle among various categories of actors committed to contrasting institutional logics’.

Universities as public institutions have experienced an invasion of corporate and markets logics into the established logic of the profession (Berman, Citation2012; Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999). The rise in prominence of the entrepreneurial university can be seen as being symptomatic of the market logic, indicative of what Berman (Citation2012) describes as a shift from ‘science-as-resource’ (logic of the profession) to ‘science-as-engine’ (logic of the market). In their seminal 2012 publication on the institutional logics perspective, Thornton et al. (Citation2012:68), (re)introduce the neglected institutional logic of the community as an institutional order: ‘communities embody local understandings, norms, and rules that serve as touchstones for legitimating mental models upon which individuals and organizations draw to create common definitions of a situation’. For the university, the logic of the community offers legitimisation in the form of ‘science-as-adhesive’ – as the pursuit and application of new knowledge that brings together and cements in place.

The institutional logics approach rests on the integration of three interinstitutional levels: society, organisation and the individual. While Clark (Citation1983) did not situate his work within the institutional logics approach, his sociological perspective adopts a similarly fine-grained ‘levels’ approach to the university as institution when he maintains that there are three layers that are characteristic of integrated higher education systems – that of the state, of university management, and of the academic heartland – and that ‘the most meaningful and successful change in the university occurs when the decentralized nature of the organization and the significant formal and informal authority of faculty and academic staff is recognized and incorporated into decision processes’ (Edelstein & Douglass, Citation2012). We suggest that only when there is internal coherence (i.e. between management and academics) at the organisational level, and institutional coherence (i.e. between the university and its institutional domain) can the university leverage its full capacity to engage in a coordinated and consistent manner with those external to the academy.

Goddard & Puukka (Citation2008:17,19) trace the position of the university as a ‘detached site for critical enquiry’ and transcendent of its physical location in the nineteenth century to one at the turn of the twentieth century that has a strong ‘territorial dimension’ to connect the university to industry and communities to facilitate innovation and public service delivery. Bank (Citationforthcoming) extracts from the literature evidence of the failure of the university as a regionally-located institution in the UK and US, and the shift in focus towards the city and urban precinct as situated spaces for university engagement. In South Africa, Bank notes the absence of a national policy framework to make the role of the university vis-a-viz development place-specific; and the engagement of the universities themselves in place-based development is uncoordinated and piecemeal. This necessitates sufficient imagination about the role of the university as a place-based actor and, in conjunction with conditions of embeddedness and normative alignment of university-community engagement, should be regarded as minimum requirements for place-specific engagement.

To explore this process and set of conditions in practice, this paper provides an overview of one university's approach to embedding engagement, and of the university's sense of place-making in the context of multiple institutional logics. The university in question is Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, or NMMU, located in the coastal city of Port Elizabeth in South Africa. The university, in South African terms, is described as a ‘comprehensive university’, that is a university that offers both theoretically- and vocationally-orientated qualifications. The university was established following the merger in January 2005 of three post-secondary institutions: the University of Port Elizabeth, the Port Elizabeth Technikon and Vista University.

This paper follows previous research on university-community engagement at NMMU. Cloete et al. (Citation2011) found a multiplicity of notions at the national and the university level on what the role of the university should be in development. They found a lack of consensus on NMMU's identity and that engagement activities occurred on an ad hoc basis instead of in a strategic, proactive and systemic manner. They also found a lack of formal coordination of linkages with business and industry, and that linkages appeared to be strong at the level of university entities as demonstrated by the development-related projects/centres situated in faculties. They also noted that the ‘academic core’ – that is, the core functions of research, and teaching and learning – of the new institution needed to be strengthened in order for NMMU to contribute effectively to development.

A second study (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2010) using data from Cloete et al. (Citation2011) confirmed the presence of multiple engagement ideologies or imperatives at the level of national policy, university management and in the academic heartland. In terms of alignment between university management and the academic heartland, the study showed that an aligned shift was taking place from civic engagement to development engagement. This shift, the study claimed, appeared to be driven by a combination of new leadership and the observable success of certain engagement activities undertaken by academics at NMMU, resulting in the diffusion of engagement as an ‘acceptable’ academic pursuit. The study found no evidence of a strong entrepreneurial imperative for engagement at the university. However, the study does make note of concern raised in relation to weak co-ordination between NMMU, government and industry, as well as between universities in the region, resulting in engagement that is predominantly reactionary and opportunistic.

A pre-merger study by Kruss (Citation2005:123) of institutional responses to the establishment of university–industry partnerships, describes the Port Elizabeth Technikon as belonging to a group of South African universities characterised by an ‘emergent entrepreneurialism’. The University of Port Elizabeth is assigned to a group of universities described as ‘laissez faire aspirational’: characteristically, partnerships between the university and industry are established in a decentralised manner, driven by individual champions in academic departments, and in an institutional policy vacuum (Kruss, Citation2005:134).

The Cloete et al. (Citation2011) study (and therefore, by implication, the Van Schalkwyk (Citation2010) study), relied on only six engagement activities for their analysis, and were weakened by category confusion (the inclusion of engagement activities [projects] and organisational structures [e.g. centres, units, etc.]) in its sampling. A more recent study (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2015) sought to remedy these limitations and to explore further at NMMU the tensions between financial and scientific imperatives observed by Kruss (Citation2005). Based on a sample of 77 engagement projects across several faculties, the study found that the degree to which engagement activities at NMMU are strengthening the university as a knowledge-producing and -transfer institution was uneven.

2. Method

This study relied on three sources of evidence to assess NMMU's engagement with external communities as being embedded and informed by place. The first relies on the strategic and policy documents of the university, and, based on a textual analysis of those documents, is a descriptive account of how a university in transition has attempted to embed engagement as a taken-for-granted academic activity in an institutional context of competing pre-merger logics.

The second and third sources of evidence rely on indicators as proxies for entrepreneurialism and place-making. Data on changes in the composition of NMMU's income – both at university and at project level – are drawn from the Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS) of the South African Department for Higher Education and Training (CHET, Citation2017) and from data collected by the Higher Education Research and Advocacy Network in Africa (HERANA) project of the Centre for Higher Education Trust on 77 engagement projects at NMMU (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2014). The same HERANA project data is used to ascertain the geographic locations of engagement projects and as a proxy for place-specific engagement.

3. Findings

3.1. Embedding engagement at NMMU: strategies and policies

The creation of a new, merged university (NMMU) was framed around the notion of a ‘new generation engaged university’, led by the former University of Port Elizabeth vice-chancellor (2003–7). The main task of the first administrator was to implement the merger. His successor's main role (post-2008) was to consolidate the process and to develop NMMU's institutional profile and identity (Pinheiro, Citation2010). A significant component of the merger and consolidation process has been to embed engagement as accepted practice. The process followed two clear phases: 2003–9 (phase 1) and 2010–15 (phase 2).

3.1.1. Phase 1: 2003–9

The proposition of the newly established NMMU being an engaged university emerged from a research project initiated by the University of Port Elizabeth, and resulted in the notion becoming part of the merger discussions at the time. The aim of the research project was to develop a vision of closer cooperation amongst the three higher education institutions, and between the higher education institutions and the city, based on a new model for development. The project culminated in a three-day conference titled ‘The University and the City: Towards an Engaged University for the Nelson Mandela Metropole’ (CHET, Citation2003).

While there was growing support for the idea of an engaged university, a redefinition of the core mission of the new university was required, as well as a restructuring of the relationship between the university and its environs. The notion of engagement was supported by the three institutions as it was located comfortably within the debates at that time about transformation and the restructuring of the national higher education system. The definition of engagement agreed upon by the conference delegates was that it was ‘a systemic relationship between higher education and its environment characterised by mutually beneficial interaction which enriches learning, teaching and/or research while addressing societal problems, issues and challenges’ (CHET, Citation2003). The conference ended with the formulation of key aspects linked to engagement which were integrated into the merger process: ‘engagement and the resulting special relationship with the Metro needed to become an integral component of the new institution's vision and mission’ (CHET, Citation2003).

Achieving institutional consensus on what the underlying philosophy and approach to engagement should be for the newly merged institution proved to be a lengthy process. The merger brought together differing views and interpretations of what constituted engagement. During this period, the debate moved from one of protection and postulation of ideas that were developed and understood within the pre-merger institutions, to a common understanding of what would work and be of value in the new comprehensive university. Overall there was no dominant view, instead there were a range of competing views. There were clear tensions between the ‘self-governing’ and ‘instrumentalist’ role that the university should play as reflected in the well-known tension between institutional autonomy and engagement (or responsiveness) (Cloete et al., Citation2011).

Therefore, an important part of this process was to develop a coherent conceptual framework on engagement as it would underpin the policies and structures required for the mainstreaming of engagement as the third mission of the university. It was understood that different conceptions and practices of engagement were unique to specific universities and that a new conceptual framework best-suited to NMMU needed to be developed as there was not a ‘one that fits all’ conceptual framework for engagement in South Africa (Muller, Citation2010). Existing definitions and interpretations of engagement had to be accommodated, aimed at achieving an institutional consensus.

The NMMU Discussion Document on Engagement (De Lange, Citation2006) presented the first draft of an engagement conceptual framework and provided the structure for further input and debate. The mission statement read as follows: ‘The Nelson Mandela University is an engaged and people-centred university that serves the needs of its diverse communities by contributing to sustainable development through excellent academic programmes, research and service delivery’. (It is worth noting here that in this 2006 mission statement the sense of place so prominent in the formulation of engagement at the 2003 conference, has disappeared.)

All policies were redrafted to meet the vision of the new merged university. Within the context of uncertainty and change, institutional cultural differences and staff insecurity, the redrafting process created the opportunity to rethink, make changes and introduce new ideas in a new university. The merger environment provided the necessary space to reconsider existing structures and ways of doing things, and to break down pre-existing structures or protected ‘empires’ and institutional cultures that had served their purpose in the pre-merged institutions. During this first phase, which ended in 2009, the policies, structures and processes for operationalising and integrating engagement into the institution's core functions were agreed on and approved across the university – both at the management level and by the university's academics.

3.1.2. Phase 2: 2010–15

During the period from 2008 to 2009, under the leadership of a new vice-chancellor, the university started the process of drafting its Vision 2020 Strategic Plan based on broad internal consultation about the future strategic direction of the institution. Following the predominantly conceptual work done in the preceding phase, Vision 2020 provided for a more structured and coordinated approach to engagement and development-related activities. It provided the necessary planning framework alongside a negotiated consensus about the identity, focus and role of the university.

The strategic plan positioned the NMMU as a new university that ‘seeks to break the mould by looking at more inclusive and sustainable ways to deliver higher education that is strongly linked to the region and communities it serves’ (NMMU, Citation2010). Vision 2020 postulated an integrative paradigm that strived to achieve connectedness between the diverse knowledge domains of the university in which it operated, and between the university and the communities it serves (NMMU, Citation2010).

Engagement would be operationalised by offering a range of qualifications spanning the knowledge spectrum from general formative academic programmes with strong conceptual underpinnings to vocational, career-focused programmes with strong links to industry and the world of work. Engagement would be integrated into the knowledge enterprise of the university by broadening the notion of scholarship:

Scholarship is invigorated and enhanced through engagement activities that enable learning beyond the classroom walls. Engagement is integrated into the core activities of the institution and cuts across the mission of teaching, research and service in a manner that develops responsible and compassionate citizens; strengthens democratic values and contributes to public good; and enhances social, economic and ecological sustainability (NMMU, Citation2010).

The strategic goals that were linked to achievement of this priority included: developing and sustaining enabling structures dedicated to advancing engagement; promoting and sustaining the recognition of engagement as a scholarly activity; and developing and sustaining mutually beneficial local, regional and international partnerships that contribute towards a sustainable future. Three new goals were added in 2013: respond to societal needs in line with institutional focus areas; promote engagement for public good; and to promote the integration of engagement, research, innovation and teaching and learning.

The role of engagement (and development) is also explicitly stated in the university's Research, Technology and Innovation Strategy. The policy states that in attaining the university vision, the institution will be able to contribute to the transformation and development of communities in terms of the full spectrum of their needs through research, technology and innovation solutions, and will continue to make a major contribution to sustainable development in Africa through research projects informed by societal needs (NMMU, Citation2007b).

As a result of Vision 2020, NMMU has attempted to follow a more coordinated and focused approach to engagement activities during the 2010–15 period. The ongoing internal debates and discussions that centred around Vision 2020 from 2008 onwards, and which culminated in the implementation of the Engagement Strategic Plan in 2010, provided the necessary impetus for a number of interventions that supported the system-wide integration of engagement into the university's academic project, and shifted the NMMU towards a more ‘instrumental’ relationship with society.

Weerts & Sandmann (Citation2008) state that universities that adopt an engagement agenda often undergo significant cultural and structural changes as they redefine relationships and expectations of internal and external partners. Kruss et al. (Citation2015) refer to institutional interface structures and the building of interactive capabilities that orient universities towards socio-economic responsiveness and inclusive development. In addition to the approval of the required engagement policy framework and related strategic plans, other internal engagement enablers have contributed to embedding engagement at NMMU.

3.2. Enabling engagement at NMMU: priorities, structures and incentives

3.2.1. Prioritising external demands and core functions

Hall (Citation2010) cautions that although engagement is normatively desirable, it should not prosper at the expense of the nurturing institution. Previous research (Cloete et al., Citation2011; Van Schalkwyk, Citation2015) found that NMMU's engagement activities were not consistently strengthening its academic core, and that this jeopardised the university's contribution to development.

Cloete et al. (Citation2011) noted that the most serious challenges to strengthening the academic core were increasing the percentage of staff with doctorates, doctoral graduation rates and research outputs. A range of interventions have been introduced since the merger aimed at strengthening the academic core. and show an increase in academic staff with PhDs and in publication units per academic staff at the same time as a concerted effort was being made to embed engagement at NMMU.

Table 1. Proportion of permanent academic staff with a post-graduate qualification.

Table 2. Ratio of publications to permanent academic staff.

The needs of external communities are always likely to exceed the capacity of the university to respond to all those needs. If NMMU believes that it should maintain a balance between responding to external developmental needs and institutional autonomy (as this allows the university to play a constructive role in addressing challenges in the external environment while remaining sufficiently independent to be able to fulfil its role as knowledge producer), then the university would need to define clearly it engagement priorities. Documentation shows that NMMU has identified engagement priorities based on its available resources and expertise, such that engagement is aligned to the research focus areas of the institution. In practice, research has shown that it is the faculties of engineering and of the arts that are most successful in terms of their engagement projects striking a balance between reaching out to external communities and strengthening the academic core (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2015).

3.2.2. Executive and senior leadership support

Leadership has been identified in many studies as a key factor in predicting sustained commitment to change as university leaders legitimise and facilitate new activities (Sandman, Citation2006; Scott, Citation2014). As part of Vision 2020, the title and responsibilities of the DVC: Research, Technology and Innovation was changed to ‘DVC: Research and Engagement’, which raised the profile of engagement within the university. The positioning of the Engagement, Research and Innovation Offices within the same portfolio, allowed for improved coordination and collaboration.

The approach of university leadership, particularly during the merger process, was key in aligning interests across academic units, and between management and university academics. The vice-chancellor at the time of the merger has been described as politically neutral and holding ‘a scientifically-informed point of view’ (CHE, Citation2015). When countering resistance to institutional change, he presented ‘first and foremost the “academic benefits”’ (Stumpf, Citation2015) of the proposed plan. In other words, leadership was mindful of the collegial and management divide, and focused on aligning their interests during the change process. While the first post-merger administrator successfully integrated the university, his successor capitalised on that organisational coherence and deployed his social capital to extend the university's links beyond industry to government and other external communities.

3.2.3. Incentives and funding

Staff development opportunities and incentives linked to engagement have been introduced at NMMU (NMMU, Citation2007a). Engagement has been included as one of the key performance areas of senior staff, particularly those in leadership positions, such as heads of department and faculty deans. More than being another performance metric to monitor efficiency, the introduction of engagement as a performance indicator was aimed at anchoring engagement projects in scholarship, as it was understood that the sustainability of engagement relied on embedding it in the norms and values of academic staff.

Other staff development opportunities and incentives include workshops on integrating engagement into teaching, learning and research; engagement-focused writing retreats; developing engagement portfolios for recognition and promotional purposes; and an annual engagement colloquium. Financial incentives for engagement at NMMU include engagement excellence awards and engagement project seed-funding.

‘Top-up’ project seed-funding is made available by the university for a maximum period of three years after which projects are required to be self-sustainable or externally funded (NMMU, Citation2012). Funding is contingent on activities that link back to the core functions of the university, and that articulate strongly with institutional policy framework and strategy. The seed funds are generated from institutional third-stream income by the raising of a 15% levy on the turnover of short learning programmes of which 5% is allocated to the Engagement Office for the provision of project seed funding. Engagement is therefore not centrally (council) funded as a separate line item, as it is viewed as a component of research and teaching funding.

A large percentage of the engagement project staff are not appointed on a permanent basis due to their employment being dependent on external project funding. These contract employees are therefore often not be fully integrated into the academic departments in which projects are located. NMMU responded with the introduction of measures to extend the contracts of project staff in order to create more permanent links between their engagement activities and the academic departments.

3.2.4. New centralised structures

As traditional academic structures tend to reinforce isolation among academics and external stakeholders, structural adjustments and a shift towards flattening the hierarchical relationship between academics and external stakeholders is required. Weerts and Sandmann (Citation2008) state that boundary ‘spanners’ are more inclusive as they allow for a two-way flow of information, and that centralised support structures act as convenors, problem-solvers and change agents that negotiate the desires and needs of stakeholders involved in the creation and dissemination of knowledge. The new structures support the emerging disciplinary culture which allows for research and teaching to occur between disciplines. And they strengthen public financial support and capacity to leverage external funding ‘as the concept of engagement fits squarely with the new generation of donors and funding agencies’ (Weerts, Citation2002).

The boundary and structural changes within the NMMU have been established in the form of an Engagement and Innovation Office, a Continuing Education Unit, incubators, university-owned companies, and a range of faculty-based research and engagement entities with centralised steering and oversight by the DVC: Research and Engagement. These porous structures have proved to be more suited to accommodate a two-way flow of information and the co-creation of new knowledge between academics and external stakeholders. With the expansion of engagement and innovation activities, the centralised and faculty-based engagement and research entities have facilitated and expanded the building of linkages with a wide variety of external stakeholders by providing the necessary transactional spaces where engagement occurs (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2015).

The engagement activities of academic entities at NMMU are centrally monitored by the Engagement Office by means of its Engagement Management Information System. The systemisation of information flows in organisations are ‘structures of resources that create capabilities for acting’ (March and Olsen, Citation2011:159) – an indicator of institutionalised norms. The entities are subjected to a review process every five years. Entity annual reports are presented at Faculty Boards, the NMMU Engagement Committee and the NMMU Research Technology and Innovation Committee before being submitted to Senate for final approval. It has been proposed that the Engagement Committee and the Research Technology and Innovation Committees be combined into one committee as this will further contribute towards an integrated approach to engagement.

NMMU has implemented a co-ordinated communication strategy between the Engagement and Innovation Offices and the Communication and Stakeholder Liaison Office. The aim of the joint communication is to maximise internal and external profiling of engagement and innovation activities at the university.

3.2. Engagement as entrepreneurialism

As the majority of the entities at NMMU are self-funded, they are dependent on external income streams, including government and private-sector funding. This has resulted in a number of the entities having to develop an entrepreneurial culture in order to remain operational. The entrepreneurial endeavours include consultancy, laboratory testing services, contract research, short learning programmes, commercialisation of intellectual property, and the creation of spin-off companies.

Kruss (Citation2005) noted different approaches to establishing partnerships with industry when comparing the University of Port Elizabeth and Port Elizabeth Technikon shortly before the 2005 merger. However, common to both was the prevalence of financial imperatives in the establishment of partnerships. This financial imperative – expressed as entrepreneurialism – would have been carried by both universities into the merged university. An analysis of documents produced by NMMU during the post-merger period reveals the continued presence of an entrepreneurial approach to engagement. Terms such as ‘commercialisation’, ‘products’, ‘innovation’ and ‘engagement income strategy’ remain in the engagement discourse.

In a 2013 survey at NMMU (Van Schalkwyk, Citation2015), leaders of engagement projects were asked what they thought the specific goals of university engagement are. Unsurprisingly, the responses were diverse: engagement provides student learning opportunities, enhances teaching and research, responds to local challenges, applies technology in line with industry needs, delivers services to the community, etc. Also among the responses was an articulation of the financial imperatives of engagement: ‘to generate third stream income through consultancy’, ‘links with industry are essential for survival’, and ‘to increase its research and consultation income’.

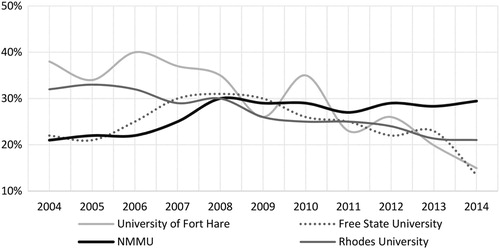

An analysis of sources of income () shows that NMMU experienced a significant increase in its proportion of third-stream income after 2007 (from 20% to 30%), and maintained this position from 2008 to 2014 while other universities in the region (Forth Hare University and Rhodes University) as well as other comprehensive universities (Free State University) saw a decline in the relative contribution of external to overall income.

Figure 1. External funding (‘third stream income’) for selected South African universities, 2004–2014.

Source: CHET (Citation2017).

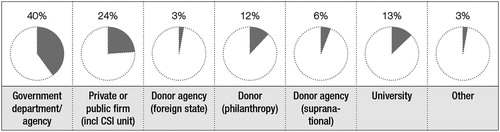

A project-level analysis of sources of funding for engagement activities () shows that the majority of project funding came from external sources (45%), with 24% of funding for engagement projects coming from industry.

Figure 2. Sources of income of engagement projects at NMMU in 2013 (n = 77).

Source: Van Schalkwyk (Citation2015).

3.3. Engagement as place-making

Being the only university in the city, with its six campuses situated across the Metro, NMMU is one of the largest property owners, rate payers, revenue generators, employers and procurers of goods and services. It has positioned itself as one of the city's ‘anchor institutions’ (Harris & Holley, Citation2016) contributing to the economic development of the city.

Since 2010, under the leadership of its second vice-chancellor, NMMU has focused on becoming a stakeholder in the development of the Nelson Mandela Metropole, evidenced by the signing of memoranda of understanding (MOU) with the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality, Nelson Mandela Bay Development Agency and the Coega Development Corporation. The MOUs are overseen by coordinating committees comprised of NMMU and Metro Council members chaired on an alternating basis by the university and the city. NMMU is an active member of the Port Elizabeth Chamber of Commerce and is a member of the Nelson Mandela Bay Strategic Intervention Forum. The university has partnered with the Nelson Mandela Development Agency on urban regeneration projects, including the regeneration of precincts around its Bird Street and Missionvale Campuses. The shift towards signing MOUs at institutional level was aimed at improved project coordination and reporting, funding opportunities and for multi-disciplinary teams to work on projects.

However, MOUs between the university and the city still need to be translated into place-based activities on the ground, and those activities take shape within a context of additional priorities set by the university in terms of regional development (for example, the NMMU has also signed MOUs with several rural municipalities, and hosts the Nelson Mandela Bay/Cacadu District Municipality Regional Innovation Forum which aims to promote innovation in the Eastern Cape Province).

A dilution in focus on the metro in its strategic documents from 2003 to 2015 has already been noted above. Data collected in 2013 on the location-specificity of 76 engagement projects at NMMU based on the site of implementation reveals the following: 12 (16%) indicated South Africa; 10 (13%) indicated the Eastern Cape Province; 20 (26%) indicated Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality; and seven (9%) indicated a specific precinct or suburb within the Metro as the site of implementation. The remainder of the projects either provided no site of implementation (18%), or indicated that project implementation was at the international level (5%) or on-campus (3%). These findings show a spread in terms of the place-specificity of engagement activities at NMMU.

4. Discussion

Holland (Citation2005) found that the early adopters of the engaged scholarship model are the younger, more locally-orientated universities with a comprehensive range of programmes. These institutions suffer under the pressures of coercive and mimetic isomorphism with the ascendency in status of the research university (propelled, in part, by the influence of university rankings), and lack national-level policy and financial support to achieve that status fully. Therefore, they struggled to create a balance between teaching (closer to their founding mission) and research. For many of these institutions, engagement has clarified their academic identity and scholarly agenda, and enhanced their quality and performance in both teaching and research. By focusing on the alignment of academic strengths with the problems faced by their surrounding communities, these universities have, according to Holland (Citation2005), developed a more specific teaching and research agenda that improved their performance.

Becoming an engaged university is organisationally-specific and institutionally bound, and is consequently dependent on engagement being embedded rather than bolted-on as an artificial organisational appendage. As Habermas and Blazek (Citation1987) notes ‘an institution remains functional only as long as it vitally embodies its inherent idea’. If engagement activities are viewed as separate and distinct from teaching and research, the ‘inherent idea’ as critical to preserving institutional functionality, is weakened. The findings show that achieving embeddedness has been fundamental to the transformation of NMMU into an engaged university – embeddedness is the combined product of its scholarly engagement architecture, organisational strategies, coherent policy framework reformulated over a protracted period by both management and academics, and the leadership provided in creating and mobilising a new merged university.

From an institutional logics perspective, NMMU's success could be interpreted as the effective blending of logics following a merger between three organisations each with its own dominant institutional logic. The Port Elizabeth Technikon observed a market logic in the form of the field-level variant of entrepreneurialism, while the University of Port Elizabeth adhered to the logic of the profession. Both logics are centred around communities – one outside of the academy and one within the academy. University-community engagement, if conceived of as being shaped by the logic of the community, possibly provided the common denominator around which a new understanding of the university's core functions could be moulded. In this sense, engagement functions as a blended field-level variation of two institutional logics.

However, despite NMMU's apparent success in embedding engagement to bridge logics, differential remnants of both logics remain. And, in particular, in a context of diminishing state funding for the university, the market logic, expressed as entrepreneurialism at the field-level, persists. The market logic promotes action premised on self-interest, personal connections and increases in efficiency and profit; in contrast to the membership-orientated, communal and reputational ideal types characteristic of the logics of both the profession and of the community (Thornton et al., Citation2012). One consequence, is engagement that is opportunistic rather than motivated by the problems of place, i.e. the challenges faced by the communities who share the city with the university. NMMU's successful integration of engagement into scholarship does mitigate against all engagement being motivated by financial imperatives. But the evidence shows that neither scholarly or financial imperatives are currently place-specific.

Thornton et al. (Citation2012) show how three ‘institutional entrepreneurs’ transformed retail, higher education and publishing in face of institutional resistance. These are entrepreneurs of a different ilk – according to Thornton et al. (Citation2012), they were able to draw on societal institutional logics different from those logics dominant in their own domains, and create new combinations of existing resources (both material and symbolic) to catalyse institutional change. The contributions of the two successive leaders at NMMU is noted in the findings above. And there is a hint of them blending non-conforming logics: the first vice-chancellor introduced a highly people-centred approach to bridge the logics of the (self-organising) profession and the corporation (new managerialism), while the second oversaw the formulation of a mission statement that defines NMMU as ‘breaking the mould’. A more in-depth examination of the histories and values of these leaders may provide further insight into how NMMU has attempted to transform itself into an engaged university.

5. Conclusion

This study has shown how through its leadership, policies and related organisational structures and incentives, NMMU has been attempting to steadily integrate engagement into its academic core. NMMU has invested in local partnerships, and its curricula and research are becoming community-focused. As an engaged university, it is increasingly generating knowledge through approaches that are more applied, problem-centred, transdisciplinary, demand-driven and responsive to external communities. As a young urban university, engagement has become embedded as a distinct element of its institutional identity.

The embedding of engagement at NMMU has created a university that is therefore, for the time being, linking effectively to those communities inhabiting the spaces outside of the university. However, while engagement with external communities is evidently place sensitive, this paper has shown that it is not yet place specific. The persistence of a market logic is a contributing factor that inhibits the university's position as a place-based anchor institution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

François van Schalkwyk http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1048-0429

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bank, L, forthcoming. A tale of two and many cities: Universities, place-making and development in South Africa. In The state of the nation 2018. Poverty and inequality: Diagnosis, prognosis and responses. HSRC Press, Pretoria.

- Berman, EP, 2012, Creating the market university: How academic science became an economic engine. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Boyer, EL, 1996. The scholarship of engagement. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 49(7), 18–33. doi: 10.2307/3824459

- CHET, 2003. The university and the city: Towards an engaged university for the Nelson Mandela Metropole. Joint Engagement Research Project. CHET Policy/Change Dialogues.

- CHET, 2017. Higher education performance data 2009 to 2015. http://www.chet.org.za/files/uploads/data/2017/SA_HE_2015_Data.zip

- Clark, BR, 1983. Higher education systems. California University Press, Berkeley.

- Cloete, N, Bailey, T, Pillay, P, Bunting, I & Maassen, P, 2011. Universities and economic development in Africa. CHET, Cape Town.

- Council on Higher Education, 2015. Reflections of South African university leaders: 1981 to 2014. African Minds, Cape Town.

- De Lange, G, 2006. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. Discussion document on engagement. Unpublished paper, Port Elizabeth.

- Edelstein, RJ & Douglass, JA, 2012. Comprehending the international initiatives of universities: A taxonomy of modes of engagement and institutional logics. Research and Occasional Paper Series: CSHE 19.12. Center for Studies in Higher Education, University of California, Berkeley.

- Goddard, J & Puukka, J, 2008. The engagement of higher education institutions in regional development: An overview of the opportunities and challenges. Higher Education Management and Policy 20(2), 11–41.

- Habermas, J & Blazek JR, 1987. The idea of the university: Learning processes. New German Critique 41, 3–22. doi: 10.2307/488273

- Hall, M, 2010. Community engagement in South African higher education. Kagisano 6, 1–52.

- Hall, B, Tandon, R & Tremblay C, (Eds.), 2015. Strengthening community university research partnerships: Global perspectives. University of Victoria, Victoria.

- Harris, M & Holley, K, 2016. Universities as anchor institutions: Economic and social potential for urban development. In Paulsen, M (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, vol. 31. Springer, Cham, 393–439.

- Holland, B, 2005. Scholarship and mission 21st century university: The role of engagement. Proceedings of the Australian Universities Quality Forum, AUQA Occasional Publications Number 5, Australian Universities Quality Agency, Melbourne, 11–17.

- Kruss, G, 2005. Financial or intellectual imperatives. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Kruss, G, McGrath, S, Petersen, I & Gastrow, M, 2015. Higher education and economic development: The importance of building technological capabilities. International Journal of Educational Development 43, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.04.011

- March, GM & Olsen, J, 2011. Elaborating the ‘new institutionalism’. In Goodin, R (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of political science. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 159–75.

- Muller, J, 2010. Engagements with engagement. Kagisano 6, 68–88.

- NMMU, 2007a. NMMU policy on academic ad Personam promotions. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth.

- NMMU, 2007b. Research, technology and innovation strategy. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth.

- NMMU, 2010. Vision 2020 strategic plan. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth.

- NMMU, 2012. NMMU policy on engagement. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth.

- Oliver, C, 1991. Strategic responses to institutional pressures. The Academy of Management Review 16(1), 145–79. doi: 10.5465/amr.1991.4279002

- Perry, DC & Villamizer-Duarte, N, forthcoming. In Bank, L & Cloete, N (Eds.), Anchored in place. African Minds, Cape Town.

- Pinheiro, R, 2010. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University: An engine of economic growth for South Africa and the Eastern Cape Region. CHET, Cape Town.

- Sandman, L, 2006. Scholarship as architecture: Framing and enhancing community engagement. Journal of Physical Therapy Education 20(3), 80–84 doi: 10.1097/00001416-200610000-00013

- Scott, P, 2014. Institutions and organizations. 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Stumpf, R, 2015. Academic leadership during institutional restructuring. In Council on Higher Education (Ed.), Reflections of South African university leaders: 1981 to 2014. African Minds, Cape Town.

- Thornton, PH & Ocasio, W, 1999. Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958–1990. American Journal of Sociology 105(3), 801–43. doi: 10.1086/210361

- Thornton, PH, Ocasio, W & Lounsbury, M, 2012. The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Van Schalkwyk, F, 2010. Responsiveness and its institutionalisation in higher education. Master’s thesis, University of the Western Cape.

- Van Schalkwyk, F, 2014. University engagement as interconnectedness: Indicators and insights. Cape Town: Centre for Higher Education Transformation. http://www.chet.org.za/files/CHET%20HERANA%20II%20Engagement%20Report%20Web.pdf

- Van Schalkwyk, F, 2015. University–community engagement as interconnectedness. In Cloete, N, Maassen, P & Bailey, T (Eds.), Knowledge production and contradictory functions in African higher education. African Minds, Cape Town, 203–29.

- Watson, D, Hollister R, Stroud, SE & Babcock, E, 2011. The engaged university: International perspectives on civic engagement. Taylor & Francis, New York.

- Weerts, D, 2002. Toward an engagement model of institutional advancement at public colleges and universities. International Journal of Educational Advancement 7(2), 79–103. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ijea.2150055

- Weerts, D & Sandmann, L, 2008. Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. Journal of Higher Education 81(6), 632–57. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2010.11779075