ABSTRACT

The integration of corporate social responsibility in existing government-funded projects geared towards community upliftment is fundamental for the restoration of humanity. The study aims to untangle the intricacies by the citizens in imposing support from government-funded projects while significantly aiming to contribute towards policy considerations, enterprises, institutions and communities. The study was approached from a case study perspective. The lessons from the case study will be integrated and synthesised within the content analytical framework. The findings from the literature review demonstrated that citizen empowerment is a critical factor that could contribute to enhanced efficiency and effectiveness in the provision of goods and services. The study recommends that there is a need for a clear regulatory framework for corporate social responsibility in the public sector. This original article contributes to the body of knowledge within the development context and public policy.

1. Introduction

The pessimistic pattern of social corporate responsibility (CSR) is still a misnomer in the contemporary allusive sense. The phenomenon is not yet legally nationalised and the concept is still nebulous. The notion of corporate social responsibility according to Chander (Citation1994:66) first occurred in the United States. It emerged around 150 years ago as a social and political reaction to the hasty evolution of capitalism following the American civil war of 1861–5. According to Frederick (Citation2006:143), CSR started to appear in the spotlight in 1951.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is no longer optional, despite the lack of clear regulation, particularly in the South African context. This is supported by Florex-Araoz who says that business enterprises ought to have legal obligations towards the stakeholders. Furthermore, CSR plays a crucial role in uplifting communities in areas such as education, health, housing, environment and safety. Companies Act no. 71 of the 2008 provisions of regulation 43 prescribes that certain ethics and social activities, values, principles and events must regulate the way in which the companies are governed.

Bitchta (Citation2001:14) reported that CSR has been prone to numerous explanations owing to reflections on the connection between business and society over time. It is emphasised in this article that, in the South African context, its principal purpose is to balance the inequalities of the past in the post- apartheid South Africa. The underpinnings emerging from discussions by scholars such as Flores-Araoz (Citation2011:5), Bitchta (Citation2001:14), Esser & Dekker (Citation2008) and Kirby (Citation2014:91) contend that it is imperative for external organisations geared for development in the area to commit certain resources towards communities.

According to Kirby (Citation2014:10), sectors must comply with the CSR requirements to ensure their explicit investment in and commitment to communities. Within this arena of activities, as a matter of priority, consideration is given to women, youth and disabled in an attempt to balance inequality. This study states that citizens should actively participate in all community initiatives and, where possible, provide goods and services needed in projects as and when necessary rather than relying on external businesses.

The South African policy outline for the provision of goods and services in the public sector, access to public services and public consultation such as the White Paper on Transforming public Service Delivery (Citation1997), the Broad Based Black Economic Act (Act 53 of 2003), the Companies Act (Act no. 71 of 2008), the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa and the King III report are reviewed to give context to the article for evidence-based recommendations. This article satisfies the substantial gap of the CSR being linked to a project pragmatically. This work will influence a change in paradigm for policy-makers to begin giving CSR attention in terms of having a clear regulatory framework to guide project implementation in all respects. Promoting CSR in business, according to Skouloudis et al. (Citation2014), could yield win–win opportunities and produce a positive effect on the regeneration of the national economy’s dynamics. It is anticipated that this study will contribute to the local economic landscape through the changes proposed in the paper. This work also provides an insight into community-level information about how CSR works in the real world.

The process flow for the community accounting framework is presented to showcase the Independent Development Trust (IDT) implementation modality in the infrastructure development projects approach. The article aims to fill a gap by relating to an incident that is explained in detail in a case study. It is in this context that this article aims to untangle the intricacies by the citizens in imposing support from government-funded projects through CSR.

The research aims at achieving the following objectives which serve as the cornerstones of the study. It aims to contribute to the community through the construct of CSR. To achieve this, a case study was found to be more relevant in fulfilling the three interrelated objectives and research questions:

to examine the power of citizens to demand CSR from government-funded projects;

to assess the responsibilities of government-funded projects within the principles of CSR towards community improvement and investment; and lastly,

to evaluate how CSR benefits communities and how insight can be provided at the community level on how CSR works.

The objectives above will answer the research questions: what is the power of citizens in demanding CSR in community projects? What is the responsibility of government towards CSR during the implementation of government-funded projects? Lastly, how does CSR benefits communities and how can insight be provided at the community level on how CSR works?

The article comprises five sections. The first one examines the background to the study, which consists of a research overview. The second section discusses the case study of the Ikageleng community in relation to CSR demands. The third section provides a literature review and examines the effects of CSR on policy imperatives. The fourth section presents a discussion of the findings in relation to discourses emanating from the theoretical debates. The final section presents the conclusions and also highlights some recommendations.

2. Background to the study

Before going any further into the debates and further discussions for demystifying the concept, it is important to define important concepts in this article, such as CSR and empowerment. Whilst the notion of CSR has advanced rapidly, in the context of this article, it is necessary to describe the concept of CSR as articulated by scholars in the field. Flores-Araoz (Citation2011:7) defines CSR as largely a voluntary contribution, or an outlay, of enterprises involved in social projects concerned with an improvement in society/the community within the jurisdiction of health care, housing, education, safety and the environment, among others. This definition is supported by Mackey et al. (Citation2007:42), who also refers to CSR as voluntary corporate actions designed to improve social conditions.

However, although the CSR definitions convey the same meaning and understanding, a difference arises from the perspective from which the concept is looked at. If it is from a social development, legal, ethical, business, science and economic perspective, there will be a level of expansion on the definition itself. This point of view has been verified by scholars such as Carroll (Citation1999:13), Porter & Kramer (Citation2011:17), Des Jardins (Citation1998:827), Esser & Dekker (Citation2008:91) and Commission of the European Communities (Citation2001, Citation2002, Citation2006). The author concurs with the definition and adds to it by stating that the CSR exists to ensure that the citizens in any given country are empowered. It is important to outline some of the critical concepts like empowerment at the outset of the discussion.

Empowerment is a complex concept and interpreted in various ways to suit specific situations. It is viewed in the context of discussion as a conferring of power to the powerless so that they can have the capacity and capability to make decisions affecting their development. When citizens possess power and are able to make decisions, this enables them to have access to resources to achieve certain goals, which is in agreement with Davis et al. (Citation2004:124). In this respect, it is noteworthy to consider De Beer & Swanepoel (Citation2004:135), who stated that people should be in possession of power in order that they can be enabled to challenge decisions and influence them as and when necessary on developments affecting their well-being, since in the absence of this power, effective participation will not occur. In reference to the case study below on the dissatisfaction of a certain portion of the community regarding the failure to contribute to the community within the CSR guidelines, this means that the Concerned Group is enabled, knows its rights, and can use them.

Drawing from the intersection of CSR and empowerment, it is of key significance to tie the two concepts together. Empowerment is embedded within CSR because, by virtue of the company investing in a community, that in itself is empowerment

2.1. Research overview

A case study was the method chosen for this study to be able to understand the origin of the problem. Yin (Citation1994:142) defines a case study as ‘an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real life context’. In this case, as Yin (Citation1994:142) has expounded, the investigation of the phenomenon did not follow a scientific approach but was conducted in an open environment where people were sharing their views openly. The exercise was pragmatic and it was also a behavioural reflection of a community project. A strong advocate of the case study approach to research is Starke (Citation1995:98), who views it rather in the light of simplifying a case than making it more complex.

This research project was conducted based on the guidelines supplied by Yin (Citation1994:143), who suggests that the case study method involves factors such as determining the present situation and gathering information about the background to the present situation. The research is performed through exploration of the case being studied and presents findings and recommendations for action.

2.2. Case study of the Ikageleng community regarding the CSR demands

As the aim of this article is to untangle the intricacies by the citizens in imposing support from government-funded projects through CSR, the details are provided in this section. The IDT (Citation2015/16) is a Schedule 2 Major Public Entity governed by its Deed of Trust, the Public Finance Management Act (Act No. 1 of 1999), as amended by Act No. 29 of 1999 (PFMA) and other relevant legislative frameworks, reporting to Parliament through the National Department of Public Works. Furthermore, the IDT is mandated to support all spheres of government in development programme implementation across the three spheres of government (IDT, Citation2015/16). The IDT has a regional office in each of the nine provinces of South Africa. It is responsible for delivering social infrastructure and social development programme management services on behalf of the government. The social infrastructure programmes include public schools, clinics, community centres and government offices, and these are predominantly in rural communities dispersed across the nine provinces (IDT Strategic Plan, Citation2016/17).

IDT tenders for social infrastructure were advertised for Bosugakobo School extension project, which is in the North West province. The tender was awarded to the contractor and consulting engineer. At the outset of the project, the social facilitator (the author of the article), who was appointed by the lead consultant and project manager to take care of all social issues and liaise between the community and the project, carried out negotiations and made arrangements with the leadership and other important stakeholders within the community prior to the project being implemented. The agreements were sealed during the project hand-over before commencement of the project activities.

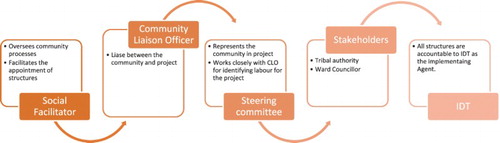

Some of the agreements were to give priority to the members of the community for providing services to the project if they qualify. It was agreed that priority shall be given to youth, women and the disabled within the limits of qualifications for those activities. The social facilitator also facilitated the appointment of the steering committee and community liaison officer, who are used as conduits to leverage opportunities arising from the project for the community. This was within the framework of the project supported by the IDT. illustrates the community accounting framework.

The project was implemented in February 2016 and in the midst of normal project execution, a dispute arising from the community group which called themselves the ‘Concerned Group’ emerged. They were not part of the community meetings during the first phase when the social negotiation processes and agreements took place. They had several complaints and demands regarding the implementing agent based on empowerment and CSR. They were demanding what they called ‘Payback’. They indicated that the implementing agent had to make a contribution to the community through the construction of a community hall to meet community need, skills development and capacity building through the utilisation of existing goods and services in the community, for example, supply of building material, labour and other resources deemed necessary. They were demanding that the contractor should give them subcontracting work so that they could utilise their own people who had already been poached by the project, leaving them with no labour.

They stated that they had experience, albeit lacking in compliance on issues like Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) grading, which is a standard requirement for building according to the legislation. They said that it was the only opportunity for them through the project to gain points which would enable them to achieve an acceptable grading. They were in a way hijacking the project but the contractor’s main concern was the quality of work. They also complained about the low rates being paid to the general labourers.

The main problem with them was that they were not engaging in mutual negotiations but demanding and stating that they were entitled, and that the contractor was obligated to fulfil their rights. They further gave ultimatums by instilling fear through intimidating practices, indicating that the project would be stopped if those actions were not implemented. The project was stopped at a later stage to the point where the community had to step in and salvage the situation. They also said that their children were grown up and so they did not care about the school. They were displaying a lack of interest in the project and also showing some level of selfishness. There was no amicable solution reached, for the reasons provided below.

The social facilitator for the project had to intervene in an attempt to resolve the disputes. She clarified the issue of CSR to them. She elucidated that the term CSR can be unambiguous and misconstrued at times if not well articulated. She informed them that:

the school building project was an initiative of the community;

the government had been approached to release funds to be able to build the school for that community;

the project was therefore a government project and the school itself was an investment by the government to the community;

before implementation, all of the authorities were consulted for buy-in, support and handing over;

the implementing team indicated to the community authorities that the project would not leave the community with nothing, that skills would be conferred during the building process, that local labourers would be utilised during construction, building material would be solicited from local suppliers, capacity would be transferred for empowerment, issues of gender, disabled and youth would be considered during employment and general participation, and there was a consensus on the undertakings presented by the implementing body; where service providers from the community qualified, they would indeed be utilised for other trades such as tiling and paving;

she illustrated to them that what was being said was practical as all of the things agreed upon were implemented; however, it was not the community’s prerogative to take over the project since an experienced contractor had been appointed to deal with all issues pertaining to building of the school;

she further said that, if they still disagreed, it would mean that they were challenging the authorities who in this instance were their community representatives;

the government did not allocate funds for CSR because there was no policy compelling them to do that;

the rates used to pay labourers were determined by the Department of Labour and those rates were augmented through the project funds;

it was also stipulated that there was no budget for CSR and big corporations like the mines were obligated to consider CSR when implementing big capital projects which caused environmental impact on communities and those big corporations could not be compared with the government;

it was also mentioned that there were certain requirements stipulated in the legislative provisions in the national government on compliance such as the National Home Builders Registration Council CIDB grading, meaning that the contractor could not just take anyone for subcontracting because they were also regulated and had to work within the regulatory framework to be able to comply to quality and standards so that they were not disqualified;

the Concerned Group was informed that they were putting their own project in jeopardy, compromising development in their area and showing that they were not in ownership of the project by delaying progress, as well as denying their children and grandchildren the opportunity to better their education;

the database forms were provided at the site office to allow the local vendors to apply and be prequalified based on the CIDB grading and others for authentication;

unfortunately, none of them qualified for bricklaying subcontracting;

she pleaded with them that they must allow construction to go on and adopt the motto of ‘going concern’ for building progress.

The community was against the Concerned Group’s allegations owing to the approach that they took and their agreement with the implementing agent. The Concerned Group ultimately surrendered and the project proceeded without any interference. The contractor appointed by government for that community-initiated project might not have budgeted for additional items on the bill of quantities; however, in terms of other resources that do not require supplementary costs, it is their duty to ensure that they leave the community empowered. Some of the services could be in a form of subcontracting qualifying people who are skilled in certain trades within the project structure. Similarly, local people should be considered for the supply of specific goods such as the material necessary for a particular project. The discussions within this article will make reference to the above case study and clarify the concerns raised.

It is important for citizens to know their rights, which in this case also means limitations to those rights, as they can be used to give negative connotations to people who can end up claiming things which they are not entitled to. The consequences of that can end up in a protest holding the government accountable. In certain instances if the government is funding a community initiative, it is an empowerment in itself which therefore does not give citizens the right to demand CSR. In that case, it will be a matter of negotiations on a win–lose basis. The above shows the third objective of evaluating how CSR benefits the communities and how insight can be provided at the community level on how CSR works. The discourse above on the solving of issues has shed light on how CSR works at a community level in the real world.

3. Literature review

There are many fallacies around CSR theory. These cause entrepreneurs to be unenthusiastic about the concept. The fallacies and myths are discussed in perspective within the theoretical debates in this section. Continuing from the earlier section where CSR was contextualised in the study background, it is necessary to continue the debates which are underpinned in the literature reviewed. It is understood that CSR is a voluntary action; Mackey et al. (Citation2007:39), Flores-Araoz; Steurer (Citation2011:12) and McWilliams & Siegel (Citation2000:603) emphasised that it exists to compensate the citizens for business operations. CSR has advantages which benefit not only the citizens but the enterprises as well. Some of the advantages as stipulated by Baker (Citation2004:63) and Horrigan (Citation2010:23) are mass media interest and good reputation, access to funding prospects, attracting and maintaining a happy workforce, enhanced relationship with stakeholders, winning new businesses and increasing customer retention. CSR can promote popularity in media, which gives the said enterprise a good reputation. Funders also give business proposals containing CSR an advantage over others. On the other hand, tax rebates are also offered to businesses practising CSR. All entrepreneurs have a legal, political and moral commitment to succeed and to ensure that they improve the quality of life of society and also leave a positive legacy.

There are also disadvantages associated with CSR, as postulated by Kleinmans, that is, costs and greenwashing. It is evident that costs can affect CSR negatively in terms of inflating the budget planned for a particular project. Greenwashing is also a problem, especially if prior consultation with the community where the project is going to be established was not done.

Scilly (Citation2013:4) views dimensions of CSR in the same light as Carroll (Citation1999:268), Porter & Kramer (Citation2011:20), Des Jardins (Citation1998:826) and Esser & Dekker (Citation2008:40). CSR is seen as contributing to economic development; businesses are expected to behave ethically, taking care of the ecological aspects of the environment. Likewise, CSR improves the quality of life and also enhances the relationship with stakeholders. CSR focuses on ecological issues such as climate change.

The issue of voluntarism entails a situation where enterprises volunteer to make a contribution to the community of their own free will. There is no legal obligation which forces the enterprises to invest in the community and there is also no ceiling in terms of how large a contribution they should make; it can only be done according to affordability, and where financial resources are lacking, there will be no legal case if there are complaints. This view is supported by Esser & Dekker (Citation2008:41) and Flores-Araoz (Citation2011:6), who indicate that CSR is based on voluntarism. Actions that are within the auspices of the voluntary dimension are not compulsory.

Skouloudis et al. (Citation2015) shed light on the perspective of CSR in terms of it being instrumental in facilitating a more mutually conditional approach towards the establishment of a meaningful CSR agenda in a community setting. Importantly, understanding the attitudes of the community towards challenging issues of socially responsible business behaviour will unlock some of their misconceptions. Skouloudis et al. (Citation2015) assert that ‘identifying and responding to concerns raised by stakeholder has a key role in enabling social capital as well as mutual learning processes’. Ulrich & Fluri (Citation1995) add that the concerns would help to manage risks and shape competitive advantages. However, the lack of awareness and knowledge of stakeholders on how CSR works in the real world can have a negative implication for the effective implementation of the project operations.

Ongoing stakeholder dialogues are key to success. This view is supported by Shah (Citation2011), who states that CSR can only materialise when enterprises take the perceptions of stakeholders into account in order to maintain social legitimacy.

It is solely dependent upon the company to decide whether it is correct to implement CSR or not. The decisions by companies are usually embedded in their policies, ethical standards and the values which they hold. Importantly, the stakeholders’ view of CSR is deemed to be essential in shaping pertinent policies, plans and programmes (Skouloudis et al. Citation2015). Cowe & Porrit (Citation2002:3) report that, in the UK, the battle between voluntarism and compulsion is at a critical stage. Importantly, with the appointment of the Minister for CSR, it means that CSR has been regulated, unlike in South Africa. Innovation and productivity are seen to be promoted by the government in the UK.

In the South African context, the Companies Act (Act 71 of 2008) does not compel companies to engage in CSR activities or projects. However, according to Esser & Dekker (Citation2008:41) and Flores-Araoz (Citation2011:6), various government policies and documents, such as the King III Report, address the need for companies to acknowledge all stakeholders and to adopt the ‘triple-bottom line’ approach. The triple-bottom line approach focuses on social, environmental and economic concerns of the organisation, which is also simplified by some scholars such as Elkington (Citation1994:96) linking them to people (social), planet (environment) and profit (economic), respectively.

During the new democratic administration since 1994, several efforts have been made to eradicate socioeconomic imbalances through various social programmes. Governments have often encouraged CSR in order to manage a wide range of governance issues. In the case of South Africa, as McWilliams & Siegel (Citation2000:603) emphasise, concern has focused on the governance implications of the shift from apartheid to democracy.

The sentiments expressed above by the courts in South Africa also resonate in the King III Report. According to Flores-Araoz (Citation2011:8) in 2002, the King II report on Corporate Governance was published concurrently with the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and requested listed companies to comply with the King report as well as compelling them to account for lack of adherence to the norm. Consequently, in March 2009 the revised version, referred to as the King III report, was adopted. Additionally, the King III report incorporated issues such as sustainability, risk and quality, while continuing to highlight the position for enterprises to respond to all stakeholders.

The clauses within the King III reports are not forceful. Another mandatory document which aims to address previous imbalances is the Black Economic Empowerment Act. The Broad Based Black Economic Act (Act 53 of 2003) is mandatory within South African-based companies to ensure that their operations are geared towards the eradication of socioeconomic inequalities, lifting marginalised groups to be active participants in the country’s economy.

The issue of putting people first, optimising access to services through empowerment and investing in citizens has been reiterated and emphasised by the government of South Africa. This is evident also in the White Paper on the Transformation of Service Delivery, the primary principle of which is to meet the basic needs of all citizens. Key programmes are also presented, which are the Reconstruction and Development Programme as well as the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Programme, which calls for, among other things, the release of resources for redirection of productive investment to areas of greatest need.

From the public policy point of view, the issue of CSR cannot be overlooked or undermined because it has negative connotations when it comes to communities owing to their lack of understanding of pertinent issues. It should not be seen as nebulous or as a misnomer since its importance has been illustrated within the discussions in this article. It should be treated as it is in other countries like the UK, Australia and most importantly the United States and be made compulsory. The action of business enterprises towards CSR should not be voluntary according to academic scholars such as Moon & Vogel (Citation2009:101) and Andriof et al. (Citation2002:224). In many countries, as Moon & Vogel (Citation2009:101) describe, CSR has been promoted by national governments, the European Union and various inter-governmental organisations, most notably the United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

In the United States, according to Flores-Araoz (Citation2011:6) and Bitchta (Citation2001:14), business enterprises which are operational have legal obligations towards the stakeholders. This view is supported by Skouloudis et al. (Citation2015) when they say that the concept of CSR is closely intertwined with increased engagement with stakeholders and integration of their concerns into core business processes. Importantly, Esser & Dekker (Citation2008:42) further explained that there are laws which require enterprises to comply with CSR to ensure that they are considerate of the interests of the society where they operate. Failure of enterprises to fulfill those mandatory obligations leads to punishment. The law is aimed at encouraging businesses to act responsibly.

5. Discussion of findings

The purpose of this section is to contextualise, explain and evaluate the underpinnings from the literature to analyse the research problem within the academic context. It is critical for all organisations regardless of sector, whether mining, environment, agriculture, construction, infrastructure development (construction), private, public or non-governmental, to support communities. The first objective is to examine the power of citizens to demand CSR from government-funded projects. As clearly stipulated in the literature reviewed, it was uncovered that the citizens should play a role in the provision of public goods and services.

Enterprises should approach CSR imperatives with mutual responsiveness towards stakeholders’ considerations and expectations. Continuous engagement with stakeholders was the order of the day for this specific project. Mahmood & Humphrey (Citation2013) support this view by adding that implementing robust multi-stakeholder platforms of dialogues with communities through roundtable regular meetings will give direction to the project and improve progress. The project implementers met with stakeholders twice a month during technical meetings and progress meetings, while the social facilitator liaised with the communities from time to time through the community liaison officer and the steering committee, who were chosen by the community to represent them in all negotiations and discussions.

It would have been irresponsible and inconsiderate for the implementers not to take the community expectations into consideration. In this specific case, the communities were engaged on the project in various building activities, such as supplying sand, water and labourers, and other subcontracting work, such as electrical wiring, tiling, paving, plastering, painting, ceiling erection and glazing, after examination of their previous work executed. The quality of work done was satisfactory. This is a long-term development trajectory which should be tapped into by other implementers. Morsing & Schultz (Citation2016) refer to this analogy as ‘sense making of a robust agenda setting’. This enables an ability to integrate the discourses of stakeholders which will eventually reflect the organisation’s capacity to strategically initiate a fruitful relationship through mutual understanding.

As has already been iterated, the South African government does not provide a legal binding framework for CSR within industry; however, other mandatory documents such as the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa and King III Report give guidance in this regard. This discussion gives impetus to the second objective, which assesses the responsibilities of government-funded projects within the principles of CSR towards community improvement and investment.

The findings show that people need to be empowered to be able to make decisions which can have a positive impact in their lives; moreover, the study demonstrates that the approach employed should be procedural, harmonious and ethical. Demanding a contribution from business by force does not always yield positive results, indicating that power is in the hands of the stakeholders through the leadership and is influenced by how they were approached initially. The project has contributed to job creation, although on a short term, and gave local businesses a reference on their business profiles which may attract more business for them in future.

It should still be borne in mind that business is primarily an economic institution but it still has a responsibility towards communities within which it operates while needing to attend to its economic interests as its main priority. This should not be misconstrued; it should be noted that business has a definite responsibility to society as Skouloudis et al. (Citation2015) view it, apart from making a profit. Importantly, a business that ignores social responsibility may have a cost advantage over a business that does not.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

Various theoretical considerations have provided a deeper insight into the concept of CSR. Governments have to take overall responsibility for ensuring that CSR is controlled properly, including the significance of sustainable development: economic, social and environmental factors. The discussion has provided answers to the objectives which were destined to untangling the intricacies by citizens through CSR.

The previous section on findings examined the power of citizens to demand CSR from government-funded projects. It also assessed the responsibilities of government-funded projects within the principles of CSR towards community improvement and investment. The final objective, which is how CSR benefits the communities and how insight can be provided at the community level on how CSR works, has also been addressed when looking at the perspectives of CSR in a community-led project.

The final discourse of this discussion is that CSR for now should be implemented without boundaries whether regulated or not. However, the discussion also states that the government should follow countries like the United States in instituting the law as well as the policies that can be crafted by departments. It is also evident that the enterprises should adhere to the principles of CSR in all respects as they also benefit in the process.

This study aims to make a significant contribution towards policy makers, enterprises, institutions and citizens on CSR aspects that they are bound to adhere to by the principles within the King III report and the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa.

The study recommends that people need to be empowered to be able to make decisions which can have a positive impact on their lives however utilising a harmonious and ethical approach to succeed. The study also reiterates that there should be law regulating all CSR activities in this regard. This article contributes to the growing body of knowledge on CSR within the development context and public policy. Metaphorically speaking, the principle of ‘batho pele’, translated as ‘people first’, should be adopted.

This study also contributes largely to the literature by offering substantive insights into the perceptions and attitudes of stakeholders and also provides insight into community-level information about how CSR works in the real world. This will add value to the Development Southern Africa journal as the study focusses on the development policy and practice in the Southern African region. This article provides area-based scholarship in the social sciences and contributes towards possibilities for policy solutions to local and regional socioeconomic development challenges. The key development issues in the region being addressed here are in terms of procedures to be followed during the implementation of projects, either for infrastructure development or business development, which in turn would contribute to poverty reduction, unemployment and local economic development within the development context. It will also persuade policymakers to debate the policy suggestions presented and argued based on evidence.

The study was limited to one project only owing to financial limitations and to narrow the scope for better focus and concentration. However, for future studies, a comparative study with implementation agencies other than national and provincial governments will be undertaken. The scope will accommodate local governments’ implementation approaches, for replication of the model to the approach of the private sector and big corporations such as WBHO, Group Five, Murray and Roberts, Stefanutti and Stocks, Aveng, Basil Read and others in the building industry towards the community in terms of CSR. These will influence the government to employ a generic approach to the implementation modality influenced also by the comparative studies employed. These will serve as a practical example while also displaying pragmatic implications pertaining to the creation of an enabling environment for strategic CSR implementation to be endorsed by all implementing parties.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andriof, J, Waddock, S, Husted, B & Rahman, SS (eds), 2002. Unfolding stakeholder thinking - theory, responsibility and engagement. Greenleaf Publishing, Greenleaf, Sheffield, UK. 20 Johnson G Scholes, K 1999. Exploring Corporate Strategy, Fifth Edition, Prentice Hall, London.

- Baker, M, 2004. Corporate social responsibility–What does it mean? http://www.mallenbaker.net/csr/definition.php. Accessed 10 December 2016.

- Bitchta, C, 2001. Corporate social responsibility a role in government policy and regulation? The Utilities Journal, CSR or Regulation? February pp. 14-15. Centre for the study of regulated industries. Published by Jan Merchant The University of Bath.

- Carroll, AB, 1999. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society 38, 268–29. doi: 10.1177/000765039903800303

- Chander, S, 1994. A study of perceived significance of social responsibility information. Journal of Accounting and Finance VIII(1), 67–77.

- Commission of the European Communities, 2001. Promoting a European framework for corporate social responsibilities, Brussels. COM(2001) 366 final.

- Commission of the European Communities, 2002. Corporate social responsibility – main issues, MEMO/02/153, Brussels.

- Commission of the European Communities, 2006. What is corporate social responsibility, Brussels. CSR)? http://europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/soc-dial/csr/csr_whatiscsr.htm [23 May 2006]. Accessed 12 October 2016.

- Cowe, R & Porritt, J, 2002. Government’s business–enabling corporate sustainability, Forum for the Future, p3.

- Davis, I, Theron, F & Maphunye, J, 2004. Participatory development in South Africa: A development management perspective. Van Schaik, Pretoria.

- De Beer, F & Swanepoel, H, 2004. Introduction to development studies. 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Cape Town.

- Des Jardins, J, 1998. Corporate environmental responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 17, 825–838. doi: 10.1023/A:1005719707880

- Elkington, J, 1994. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review 36(2), 90–100. doi: 10.2307/41165746

- Esser, IM & Dekker, A, 2008. The dynamics of corporate governance in South Africa: Broad based black economic empowerment and the enhancement of good corporate governance principles. Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology 3(3), 157–69.

- Flores-Araoz, M, 2011. Corporate social responsibility in South Africa. More than a nice intention. In On Africa. www.inonafrica.com. Accessed 10 December 2016.

- Frederick, WC, 1987. Theories of corporate social performance. In Sethi, SP & Falbe, C. (Eds.), Business and society. Dimensions of conflict and cooperation (142–161). Lexington Books, New York.

- Frederick, WC, 2006. Corporation, be good: The story of corporate social responsibility, 334. Dog Ear Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

- Horrigan, B, 2010. Corporate social responsibility in the 21st century. Debates, models and practices across government, law and business. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK.

- IDT, 2015/16. Independent development trust strategic plan 2015/2016. http://www.idt.org/za/strategic-plan. Accessed 19 October 2016.

- IDT, 2016/17. Strategic plan. http://www.idt.org.za/strategic-plan. Accessed 13 December 2016.

- Kirby, N, 2014. What’s really right? Corporate social responsibility as a legal obligation in South Africa, Johannesburg. Legal Brief, February.

- Mackey, A, Mackey, TB & Barney, JB, 2007. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance. Investor preferences and corporate strategies. Academy of Management Review 32(3), 817–35 York, Lexington Books. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.25275676

- Mahmood, M & Humphrey, J, 2013. Stakeholder expectation of corporate social responsibility practices: A study on local and multinational corporations in Kazakhstan. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20, 168–81. doi: 10.1002/csr.1283

- McWilliams, A & Siegel, D, 2000. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. The Academy of Management Review 30 10 (366) final, 166–79.

- Moon, J & Vogel, D, 2009. Corporate social responsibility. government, and civil society. The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Morsing, M & Schultz, M, 2006. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Business Ethics: A European Review 15, 323–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00460.x

- Porter, M & Kramer, M, 2011. Creating shared value. How to reinvent capitalism-and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review 18(2).

- Scilly, M. 2013. Four types of corporate social responsibility. http:smallbusiness.chron.com//four-types-corporate-social-responsibility-54662.html. Accessed 4 November 2016.

- Shah, KU, 2011. Corporate environmentalism in a small emerging economy: Stakeholder perceptions and the influence of firm characteristics. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 18, 80–90. doi: 10.1002/csr.242

- Skouloudis, A, Chymis, A, Allan, S & Evangelinos, K, 2014. Corporate social responsibility: a likely causality of the crisis or a potential exit strategy component? A proposition development for an economy under pressure. Social Responsibility Journal 10(4), 737–55. doi: 10.1108/SRJ-02-2013-0015

- Skouloudis, A, Evangelinos, K & Malesios, C, 2015. Priorities and perceptions for corporate social responsibility: An NGO perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22(2), 95–112. doi: 10.1002/csr.1332

- Starke, R, 1995. The art of case research. Sage Publications, Thousand oaks, CA.

- Steurer, R. 2011. Disentangling governance: A synoptic view of regulation by government, business and civil society. Policy Sciences 46(4), 387. doi: 10.1007/s11077-013-9177-y

- Ulrich, P & Fluri, E, 1995. Management: Eine konzentrierte einführung (Management: A concise introduction). Campus, Berne, Switzerland.

- White paper on transforming public service delivery, 1997 . Department of Public Service and Administration. Pretoria.

- Yin, RK, 1994. Case study as a research method. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.