ABSTRACT

Building on the model of Meyer [(2007). Pro-Poor tourism: from leakages to linkages. A conceptual framework for creating linkages between the accommodation sector and ‘poor’ neighbouring communities. Current Issues in Tourism 10(6), 558–83], this paper focuses on the regional development potential of local linkages with the supply chain and community partnerships of established tourism businesses in western Uganda. Results show that supply-related inconsistencies of local produce undermine the existence of supply chain linkages with local farmers, and favour business linkages with local intermediary suppliers, dominantly shaping the regional development potential of supply chain linkages in western Uganda. Yet, this research found several ‘windows of opportunity’ for local suppliers to connect to the tourism value chain. Results on community partnerships suggest that most businesses do not move beyond the absolute minimum partnership intensity that is required to be able to strategically use for marketing purposes and obtain a unique selling proposition. Finally, our research exposes the complexity of locating responsibility among different stakeholders of the value chain in suggested paths for (regional) development.

1. Introduction

As tourism induces economic activities to peripheral rural and economically marginal areas, the sector is regarded as a lever for development purposes in these contexts (Kauppila et al., Citation2009). Since the post-war period, the role of tourism in the development debate and the meaning of the development concept as such evolved under different dominant paradigms, predominantly based upon comparing economic levels of growth between ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ parts of the world (Holden, Citation2013). In addition, conceptualisations of the relationship between tourism and development changed in time based on the theoretical approaches of modernisation, dependency, economic neo-liberalism and alternative development (Thomas-Francois et al., Citation2017). However, given the potential of tourism to contribute to development, several authors indicate that linkages between the development theory and tourism remain limited (Holden, Citation2013).

However, there has been a clear ‘impasse’ concerning the different routes to development over the last decade, ‘characterized by considerable disillusion with all major theories on development’ (Harrison, Citation2015:60). The realisation of shortcomings of grand theories of development is also reflected in current approaches to tourism, in which researchers embraced postmodern, postcolonialist and post-structuralist thoughts, leading to a post-development way of thinking (Harrison, Citation2015). This post-development perspective ‘contest the value of grand theories of development that suggest single ways of understanding the world, and all share an interest in power relations’ (Scheyvens, Citation2011:42). In the meanwhile, many scholars criticise the tourism sector for not completely realising its regional development potential in these countries. In these countries, this potential is reduced because linkage opportunities between the tourism sector and local communities, also known as local value chain linkages,Footnote1 are seldom maximally established in tourism value chains (e.g. Adiyia et al., Citation2015).

Nevertheless, several scholars argue that research on local value chain linkages and their role in the regional development potential of tourism remains incomplete (e.g. Meyer, Citation2007; Anderson & Juma, Citation2014). The linkage formation process is driven by a wide set of complex establishing mechanisms, and the establishment of local linkages in many economically less developed destinations has failed due to various challenges of demand-related, supply-related, marketing-related and institutional-related nature (Anderson & Juma, Citation2014). More specifically, Pillay and Rogerson (Citation2013:49) argue that ‘questions surrounding the establishment of linkages between tourism establishments and local food producers are little documented’, especially in African tourism scholarship. Secondly, parallel to various recent claims that donors and governments have failed to eliminate poverty, the private sector has become the focal point to take a greater and more direct role in development (Banks et al., Citation2016). Yet, the nature and effects of ongoing private sector community initiatives are still under-researched (Banks et al., Citation2016).

In this research context, this paper analyses the regional development potential of local linkages with the supply chain and community partnerships of the tourism sector from a private sector perspective. The paper focuses on western Uganda as a case study in Sub-Saharan Africa, as the Ugandan government tries to use tourism as a strategy to alleviate poverty and develop rural areas (Ministry of Tourism, Citation2013). In-house responsibilities, such as employment, have been extensively studied over the past decade among others in the study area, and are therefore beyond the scope of this paper (e.g. Adiyia et al., Citation2014; Snyman, Citation2014).

2. Broadening the value chain approach

Recent studies confirm that value chain based analyses (VCAs) are appropriate to understand the regional development potential of tourism in economically less developed countries (e.g. Spenceley & Meyer, Citation2012; Mitchell et al., Citation2015). Value chains originate from economic and business studies, conceptualised by Porter (Citation1980:36) as ‘a collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support its product’. Put in another way, value chains comprise a process view of which subsystems, each with inputs, create the provision of a service in different steps; each step generates an additional value compared to the previous step (Hjalager et al., Citation2016). Originally, value chains functioned as a tool to manage the competitive advantage of single firms in traditional manufacture, while a business aims to be profitable by creating an amount of total value that exceeds the total costs (Porter, Citation1980; Gereffi & Korzeniewicz, Citation1994). Due to globalisation and fragmentation, the specialisation of firms and the division of labour, different activities within the value chain are often carried out by firms located in different countries (Romero & Tejada, Citation2011). In this regard, the concept of global value chains emerged, integrating different value chains carrying out value-adding activities required to bring a product or service from the design phase, through the production and marketing phase to the distribution and final disposal or recycling stage after use (Romero & Tejada, Citation2011). Global value chains differ from Porter’s definition of a value chain in the sense that they are also interested in relations between different agents participating in the value chain. Value chains are no longer solitary chains but are interlinked in global networks (Romero & Tejada, Citation2011). Global value chains imply stakeholder linkage interactions (Kaplinsky & Morris, Citation2000). Governance ensures that interactions reflect a degree of organisation instead of occurring at random.

In tourism, individuals, organisations and firms collaborate to produce and distribute sustained value for tourists, while generating profit for themselves (Romero & Tejada, Citation2011). Accordingly, Mitchell & Ashley (Citation2010:16) define tourism value chains as ‘all elements of providing goods and services to tourists, from supply of inputs to final consumption of goods and services, and [this] includes analysis of the support institutions and governance issues within which these stakeholders operate’. In reality, value chains are complex to analyse and to define due to their multi-layered dimension and intangible structure (Kaplinsky & Morris, Citation2000; Mitchell, Citation2012). Its understanding is further complicated by the fact that the tourism value chain integrates services that do not consist of a well-defined ‘sector’, certainly when expanding at an international level.

In an attempt to assess the sectors’ regional development potential, Mitchell & Ashley (Citation2010) developed a simplified VCA-based model comprising the different pathways by which tourism can impact local economies (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2010). The modelFootnote2 reflects three pathways through which tourism can contribute to poverty alleviation and regional development, namely via primary, secondary and dynamic effects on the local economy. Going back to the value chain perspective, it becomes clear that the multitude of stakeholders and scales makes us drift away from the original input-output models, traditional economic added value, and economic multiplier effects. According to Kaplinsky & Morris (Citation2000), value chain analysis comprises identifying the type of value chain, the barriers to enter the chain and governance issues related to links between stakeholders in the chain. The post-development perspective on development stimulates analysis of stakeholder interactions of powerful stakeholders and their influence on their approach to development (Scheyvens, Citation2011). In this regard, the focus of this perspective on power relations is further reflected by the multi-scalar and multi-sectoral characteristics of the tourism system that give rise to a value chain in which stakeholders both compete and cooperate, generally resulting in power imbalances where each stakeholder tries to derive a larger share of value by gaining more power (Bramwell & Meyer, Citation2007).

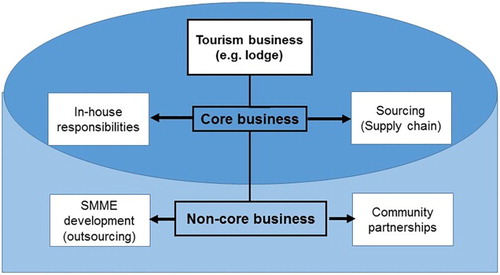

In this context, Meyer (Citation2007) developed a simplified framework distinguishing different types of linkages based on an extensive review of the academic literature on tourism and development. The framework makes a distinction between a business’s core and non-core competenciesFootnote3 as it is argued that activities related to the core and non-core business have different impacts on poverty reduction. Accordingly, the framework contains four different types of local value chain linkages: (1) in-house responsibilities, (2) supply chain linkages, (3) Small Micro and Medium Enterprise (SMME) development and outsourcing, and (4) community partnershipsFootnote4 ().

Figure 1. Different types of linkages between tourism businesses and the local economy (adapted from: Meyer, Citation2007).

3. The competitive advantage of strategic linking

From a corporative perspective, there are many motives to create local value chain linkages, ranging from commercial interests to corporate social responsibility (CSR) as they both shape the success of an enterprise in several ways. From a commercial point of view, the enterprise’s success is influenced by its supporting companies and surrounding infrastructure (Porter & Kramer, Citation2002, Citation2011). Accordingly, tourism businesses apply strategies aiming at an optimal logistical efficiency for core and non-core competencies in terms of local labour and suppliers (Ashley & Mitchell, Citation2006; Vanneste & Cabus, Citation2007). The nature of inter-firm network links ranges in a continuum from ‘loose’, informal relation-based linkages to structural, formal contract-based links as inter-firm network links are partially based on qualitative cooperation mechanisms such as trust and personal commitment (Beritelli, Citation2011). Loosely organised networks are prevalent among SMMEs and generally aim to deliver short-term profits, while formal distribution networks are generally established for long-term inter-firm coordination purposes in both core and non-core competencies (Beritelli, Citation2011).

As for CSR, customer satisfaction plays an important part. Tourism businesses can modify customer satisfaction by manipulating their business environment, since experience value can be undermined by local poverty and hostility, or conversely, can be intensified by supporting local products and communities (Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2006). In addition, CSR practices positively influence the motivation and commitment of employees, even in terms of recruitment (Garay & Font, Citation2012). In settings with extreme differences between basic amenities available to local people and luxuries available to international guests, businesses feel obliged to provide goods and services to adjacent communities (Banks et al., Citation2016). Hence, CSR in tourism is often adopted for its long-term commercial value, providing a unique selling proposition, while improving the business’s reputation by positive publicity and increasing the overall corporate financial performance (Ashley & Mitchell, Citation2006; Meyer, Citation2007; Garay & Font, Citation2012).

4. Study area and methodology

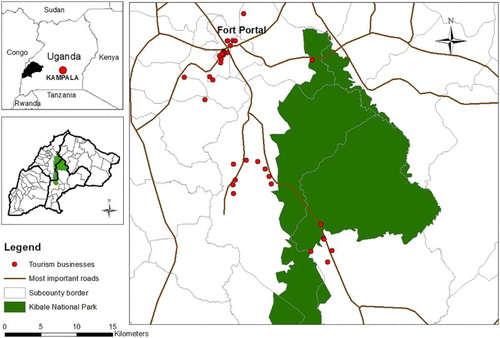

Tourism in Uganda largely focuses on the western part of the country, as this region encloses most comparative advantages and tourism attractions. National policy arrangements that should compensate communities for tourism and conservation costs, such as human-wildlife conflicts, have achieved mixed outcomes in western Uganda (Ahebwa et al., Citation2012). In this regard, this paper focuses on western Uganda, and more precisely, on the region around Kibale National Park (KNP, ). KNP is a popular destination for its primate tracking activities, and the area is included in the itineraries of most international tourists visiting Ugandan national parks (Adiyia et al., Citation2015). In 2012, KNP attracted more than 10 000 visitors, ranked fourth among national parks in Uganda (UBOS, Citation2013). KNP’s surroundings are characterised by limited off-farm livelihood options, high population densities between 270 and 315 inhabitants/km2, an annual population growth of 3.3%, and ca. 45% of the households living under the international poverty line of US$2/day (Adiyia et al. Citation2017). Since the opening of KNP in 1993, small-scale tourism accommodationsFootnote5 have popped up in the urban environment of Fort Portal and in a more rural environment near the park’s entrance (Adiyia et al., Citation2014).

During fieldwork (July–September 2013), information was collected from 77 semi-structured interviewsFootnote6 with tourism businesses and their suppliers. The following stratified sample design was utilised to collect data. First, a complete register of established tourism businesses was created by consulting local district offices, non-participant observation, snowball sampling, and the Bradt tour guide (Briggs & Roberts, Citation2010). Subsequently, information from established tourism businesses was collected by semi-structured interviews with business owners, managers or managing directors to inquire about the establishing mechanisms and impacts on regional development of supply chain linkages and community partnerships. lists all interviewed tourism businesses for this research. Based on an extensive literature review, the authors tabulated different types of supply chain linkages and community partnerships that were used as a conceptual framework to create the interview protocol to identify local linkages in the field (). In a next step, information from tourism businesses was cross-checked by interviewing their suppliers and local representatives of community partnerships. Further, seven focus group interviews with community members in the vicinity of selected tourism businesses were conducted to crosscheck information. All respondents were able to choose the language of the interview. Most interviews were conducted in English, but some interviews were conducted in the local language (Rutooro, Rukiga) with the support of a translator. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, read and coded with qualitative data analysis software NVivo® 10.

Table 1. List of interviewed tourism businesses in the study area.

Table 2. Different types of supply chain linkages and community partnerships.

5. Results

5.1. Supply chain linkages

Evidence from interviews with tourism businesses shows that food supply and cultural tourism linkages are dominantly present in the study area in terms of supply chain linkages. Interviews with tourism businesses reveal that basic food items, such as fruit and vegetables, are commonly procured from farmers and intermediary suppliers (so-called ‘middle men’) on local markets. In the decision-making of food procurement, ‘getting value for money’ is unanimously referred to by all tourism businesses as the most dominant variable in the decision-making of food procurement. Yet, business owners confirm the existence of several demand- and supply-related challenges for local food procurement, such as inconsistencies in quality and quantity to meet the standards of international tourists. In addition, business owners indicate that price fluctuations of food items are common as a result of the agricultural seasonality and the local negotiating culture. More specialised food items, such as meat, fish, spices, pastas and rice are not locally produced or do not meet the targeted tourist standards. They are therefore bought in local supermarkets in Fort Portal that import products from the capital (Kampala), or are directly purchased by the tourist businesses themselves in Kampala. The decision-making process of purchasing building materials is analogous with the decision-making of food procurement: basic items are purchased in Fort Portal, while more specialised items are not found in the area and are for that reason imported from Kampala.

We would like to go straight to the farmers but the inconsistency on that … Because the farming itself is not even consistently able to provide you with produce. You have to use various farmers to get consistent produce. Because they don’t use cycles so they can have continuous produce. (supply officer lodge, tourism accommodation)

It could be good if they came into our village and bought yellow bananas and vegetables, but they don’t. They buy bananas and vegetables from town. (focus group Kyaninga village)

Every time you do business with someone, it’s as if you do business with him for the first time. You have to renegotiate from first, volume doesn’t get you even buying power. Because the local suppliers only focus very much on today and not tomorrow … They just want to move the product that they have today. (manager hotel)

We prefer to get more local suppliers and we have tried them, but they fail. It’s not easy to find one person who can deliver every time, the same quality, the same quantity. (manager guesthouse).

A lot of our staff are from this area, so we told them: ‘tell your friends and your family that if they can grow things and bring them up, we will buy them’. (manager lodge)

The lodge used to pay for their [the cultural group’s] transport, but there was a query from Kampala about the money that goes [is spent], so it [the payment] stopped. (manager lodge)

Some time back we used to go to the lodges, and we negotiate about the price. We tell that they pay like 10 000 [Ugandan Shilling] per tourist, but now, [there is] no negotiating [anymore] because of the competition. There is too much competition. So now, when we go and dance, we put the basket and everybody puts in [money] from the bottom of his or her hearth in the basket to donate for us. (Cultural Performance Group)

5.2. Community partnerships

Interviews with business owners suggest that the majority of tourism businesses are involved in establishing community partnerships.Footnote7 However, several focus group interviews and interviews with representatives of community partnerships contradict the continuous commitments of tourism businesses, while revealing that most businesses are only very occasionally engaged in a community project:

The needs to help communities are here, but people are not willing to. Those [tourism business owners] are businesspeople, not people out to help the country. They’re just here to make money, they’re not here for community development … That’s business … I’m not criticizing, that’s just what they are. (NGO with a tourism accommodation)

Let me put it this way: are we pro getting involved with the community? No, we are a private business and I think that’s all about the bottom line, unfortunately, at this point. Will we be doing it in the future? Maybe, yes, because from a management perspective I’m pro. (manager lodge)

The unique thing about us is how far it goes back. My granddad was here, my dad was here, I’m here. (…) Most of them [business owners] have no desire to live in that place or to have anything to do with the locals, but they probably have some sort of local community project because they feel obliged rather than driven to do it. (lodge owner)

The mzei [old respected man] initiated so many things with the community here. (…) He sensitized the community to come up with a craft center, and he bought an expensive sideboard to sell the crafts without charging anything. He was trying to attract the community to participate in tourism. (…)These [new] people don’t allow the community to interact with the tourists. You know, for them, they want to make more money for their company, more money, more money. (local tour guide, Amabere Caves)

They [new owners] have adopted different cultures from where they grew up. These people they went abroad and now they have just come because of the death of their dad. So they are not associated with the community, they don’t want to know more about the community and their problems, you know. (Focus group interview, Kaliango)

6. Discussion

Results on supply chain linkages show that these linkages aim to deliver short-term profits to both buyers and suppliers. These linkages can be considered as a network of loosely constructed relationships, based on business-to-business transactions with a short-term vision, while local markets function as an informal platform for procuring basic food supply linkages. In addition, results show that supply-related inconsistencies jeopardise the existence of these linkages, and stimulate the replacement of informal linkages with local farmers towards semi-formal linkages with local intermediary suppliers as strategic mechanisms for consistent product prices, qualities and quantities.

Accordingly, our findings are in line with Pillay & Rogerson (Citation2013:56) who argue that the food supply chain ‘is articulated mainly through a network of intermediaries with linkages that only marginally incorporate the region’s groups of poor agricultural producers’. Evidence from interviews also indicates that a strict top-down model of managing tourism businesses strengthens the creation of a tourism value chain with limited opportunities for local entrepreneurs. Accordingly, our findings mirror previous research that identified constraints in establishing local supply chain linkages in sub-Saharan African countries (e.g. Rogerson, Citation2012; Pillay & Rogerson, Citation2013).

Yet, results found several ‘windows of opportunity’ for local suppliers to connect to the tourism value chain. First, findings on the intermediary role of staff employees in food procurement of tourism businesses underline the role of qualitative cooperation mechanisms such as trust and familiarity in building relation-based linkages (Beritelli, Citation2011). Accordingly, the tourism sector enables opportunities for local communities to connect with the informal sector. Second, it was noted that willingness among established tourism businesses existed to connect to local farmers. Third, analysis shows that the intermediaries between local farmers and tourism businesses, the so-called ‘middle persons’, are part of local communities and procure food items from farmers that lack the financial means to transport their produce to the market. As such, intermediaries connect local farmers that would else be excluded from the market, and thus from supply chain linkages with tourism businesses.

Results on community partnerships reveal that most tourism businesses pretend being continuously engaged in these partnerships to strengthen their marketing position. Despite that the term ‘partnership’ suggests an agreement between both parties, most initiatives were formed on occasion or for a single time. As such, businesses move away from purely philanthropic actions and focus on ‘second generation CSR’, while incorporating CSR as an integral part of the business’s long-term strategy. Furthermore, results suggest that the role of external donors and NGOs is key in establishing consistent and continuous community linkages with the private sector, since only few foreign businesses with core competencies in community development facilitate continuous and consistent community partnerships. This result should be interpreted with caution, since both the study area and tourism literature are strewn with numerous examples of deteriorated small-scaled projects initiated by well-intentioned NGOs that (1) were heavily reliant on donor funding and collapsed when funding ended, (2) were not incorporated in the market regulation mechanisms of the mainstream tourism industry, and (3) did not take into account local livelihood-based survival contexts (Meyer, Citation2009). In addition, it is clear that the degree of local embeddedness strongly influences the decision-making of businesses with core competencies in tourism to get involved in community partnerships. In the literature, these businesses are called ‘social enterprises’ or ‘social activitist’, referring to enterprises that have implemented the practice of doing business differently by their passion to contribute to regional development (Spenceley & Meyer, Citation2012).

As such, our findings show that these social enterprises can act as a developing agent that balance commercial and developmental objectives. Accordingly, the tourism sector could play a pivotal role in ongoing changing modes of consumption towards more ethical and responsible consumption and production among all stakeholders (Saarinen, Citation2014). In this regard, tourism businesses have started to include local communities in their value chains by developing ‘inclusive business models’ (IBMs), which can be referred to as ‘profitable core business activities that also tangibly expand opportunities for the poor and disadvantaged in developing countries’ (Business Innovation Facility, Citation2011:1). It is critical for local development purposes that IBMs redefine existing core competencies as such that small enterprises and local communities are maximally involved in local supply chains. Therefore, a business should identify all ‘societal needs, benefits and harms that could be embodied in the firm’s product’ (Porter & Kramer, Citation2011:76). In addition, in order to successfully tap into the value chain, it is equally important to (1) resolve the lack of communication between buyers and suppliers, (2) create a skilled entrepreneurial attitude in the minds of local suppliers and an awareness in local communities to develop quality products, (3) govern the value chain in a way that stimulates local suppliers to overcome barriers to enter the tourism sector.

7. Conclusion

Building on the model of Meyer (Citation2007), this paper analysed the regional development potential of supply chain linkages and community partnerships in western Uganda. Evidence from semi-structured interviews with tourism businesses, suppliers, community projects and focus group interviews confirm that supply chain linkages are partially based on informal trust-based relations in which buyers primarily aim at getting (1) value for money and (2) consistent product prices, qualities and quantities. However, supply-related inconsistencies of local produce undermine the existence of supply chain linkages with local farmers, and favour business linkages with local intermediary suppliers, dominantly shaping the regional development potential of supply chain linkages in western Uganda. Results on community partnerships suggest that most businesses do not move beyond the absolute minimum partnership intensity that is required to be able to be strategically used for marketing purposes and obtain a unique selling proposition. In addition, our findings suggest that moving beyond tokenistic efforts and the involvement in continuous community partnerships is strongly influenced by the degree of local embeddedness of businesses that have a passion to contribute to regional development. The importance of local embeddedness in communities supports Niewiadomski (Citation2013) who argues that, as businesses move away from operator-owning to consortium management practices, they become less embedded in and therefore less committed to local communities.

Furthermore, partnerships are difficult to establish when power imbalances and different goals and values exist among different parties, in this case tourism businesses and local communities. While the development perspective places human wellbeing of local communities to the front, business growth and economic development are likely to be the top priorities of the private sector perspective. Progress can only be made by increasing overlapping areas of interest and decreasing tensions that arise from competing values. Currently, CSR initiatives of tourism businesses in other destinations of economically less developed countries generally deal with the symptoms of maldevelopment rather than dealing with its the causes. In the meanwhile, it is clear that local farmers in western Uganda and other parts in Sub-Saharan Africa should raise their game to participate in the food supply chain of tourism businesses. Under current supply chain management practices, limited progress can be made in terms of regional development potential. Despite the willingness of tourism businesses to cooperate with local suppliers, structural collaborations between both parties are hampered by short-term thinking, and lack of entrepreneurship and strategic thinking of local suppliers. Awareness among suppliers of hotel and restaurant product requirements, health and safety regulations and tourist preferences is not sufficient to deal with existing limitations of supply chain management practices. Local producers in western Uganda need a total shift of attitude that moves away from (donor) dependency thinking towards perceiving farming as a business with career possibilities, while becoming accountable entrepreneurs to supply the tourism sector. The government has a role to develop this shift from kindergarten onwards. In addition, local farmers and farmers’ associations need financial credit to invest in upgrading their production for the tourism sector, and good infrastructure that connects farmers to their suppliers and buyers. Governmental incentives, such as providing marketing materials for promotion purposes, tax benefits and the accreditation of tourism businesses that purchase from local farmers, could be given to encourage the private sector to include local SMMEs in their supply chains.

8. Critical reflections and scope for further research

The role of the private sector has been foregrounding in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the new standards of international development policy and practice (Banks et al., Citation2016; Hughes & Scheyvens, Citation2016). Businesses, governments and civil society have become ‘equally called upon to pursue a more sustainable path forward’ in the post-2015 development era, driven by the belief that governments have failed in their attempts to clear the planet from under-development, inequalities and poverty (Scheyvens et al., Citation2016:371). Yet, our results show that the regional development outcome of community ‘partnerships’ is by far smaller than its (theoretical) development potential. To maximise local value chain linkages, regional development needs to be in the interest of the consumers as well. A high consumer demand and the willingness to pay (extra) for responsible tourism practices would definitely be an incentive to increase socio-environmental performances of the private sector.

Let us go a step further and question whether the consumer is willing to capture momentum and fulfil its role towards narrowing the gap between the regional development potential and the regional development outcome of tourism in economically less developed areas. Consumers prefer to deal with a favourable version of local reality, instead of having a persistent urge to face the actual reality. Although there exists a general understanding of thinking globally, while contributing towards more local and responsible consumption patterns, the reflection to change personally is often lacking, postponed or becomes temporarily ‘blurry’ during the holidays.

Finally, this research shows that the classical value chain approach does not grasp all dimensions of development. Power issues and failing modes of (neoliberal) governance induce uneven development outcomes of the chain as well. Moreover, it is not straightforward to use value chain analysis as a tool to evaluate economic success, as not all products can be locally produced and procured. This paper exposes the complexity of locating responsibility among different stakeholders of the value chain in suggested paths for (regional) development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Local value chain linkages can be defined as ‘a variety of ways in which well-established businesses can build economic links with micro-entrepreneurs, small enterprises and residents in their local economy’ (Ashley & Mitchell, Citation2006:1).

2 The authors refer to the primary source for further details.

3 In this regard, core competencies refer to ‘unique disciplines that confer competitive advantage, motivating customers to buy a company’s goods and services over a competitor’ (Robinson, Seaf, & Kantor, Citation1998:2).

4 Community partnerships cover ‘all initiatives that a company undertakes to support the neighbouring community’ (Meyer & Goodwin, Citation2006:14).

5 Other tourism businesses such as tour operators, restaurants and non-park-related tourist attractions are only scarcely present in the tourismscape (Adiyia et al., Citation2014).

6 The sample contains 34 accommodations, two tour operators, one restaurant, four tourist attractions, 24 local suppliers and 12 community projects.

7 Examples of community partnerships comprise building an orphanage for HIV positive children, setting up community awareness projects around agriculture, general hygiene or HIV, building primary schools, developing schools for tour guiding, etc.

8 Examples of external donors that work in the study area are Adventist Development Relief Agency (ADRA), Youth Encouragement Services (YES) and Kwataniza.

References

- Adiyia, B, Vanneste, D, Van Rompaey, A & Ahebwa, W, 2014. Spatial analysis of tourism income distribution in the accommodation sector in western Uganda. Tourism and Hospitality Research 14(1–2), 8–26. doi: 10.1177/1467358414529434

- Adiyia, B, Stoffelen, A, Jennes, B, Vanneste, D & Ahebwa, WM, 2015. Analysing governance in tourism value chains to reshape the tourist bubble in developing countries: The case of cultural tourism in Uganda. Journal of Ecotourism 14(2–3), 113–29. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2015.1027211

- Adiyia, B, Vanneste, D & Van Rompaey, A, 2017. The poverty alleviation potential of tourism employment as an off-farm activity on the local livelihoods surrounding kibale national park, western uganda. Tourism and Hospitality Research 17(1), 34–51. doi: 10.1177/1467358416634156

- Ahebwa, W, van der Duim, R & Sandbrook, C, 2012. Tourism revenue sharing policy at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda: A policy arrangements approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 377–94. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.622768

- Anderson, W & Juma, S, 2014. Linkages at tourism destinations: Challenges in Zanzibar. ARA Journal of Tourism Research 3(1), 27–41.

- Ashley, C & Mitchell, J, 2006. Tourism business and the local economy: Increasing impact through a linkages approach. ODI Briefing Paper. Overseas Development Institute.

- Banks, G, Scheyvens, R, McLennan, S & Bebbington, A, 2016. Conceptualising corporate community development. Third World Quarterly 37(2), 245–63. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1111135

- Beritelli, P, 2011. Cooperation among prominent actors in a tourist destination. Annals of Tourism Research 38(2), 607–29. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.11.015

- Bramwell, B & Meyer, D, 2007. Power and tourism policy relations in transition. Annals of Tourism Research 34(3), 766–88. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.03.009

- Briggs, P & Roberts, A, 2010. Uganda (p. 528). Bradt Travel Guide, Guilford, CT.

- Business Innovation Facility, 2011. What is inclusive business? Business Innovation Facility and Innovations Against Poverty, London.

- Garay, L & Font, X, 2012. Doing good to do well? Corporate social responsibility reasons, practices and impacts in small and medium accommodation enterprises. International Journal of Hospitality Management 31(2), 329–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.04.013

- Gereffi, G & Korzeniewicz, M, 1994. Commodity chains and global capitalism. Praeger Publishers, Westport.

- Harrison, D, 2015. Development theory and tourism in developing countries: What has theory ever done for us?, International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 11, 53–82.

- Hjalager, A, Tervo-Kankare, K & Tuohino, A, 2016. Tourism value chains revisited and applied to rural well-being tourism. Tourism Planning & Development 13(4), 379–95. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2015.1133449

- Holden, A, 2013. Tourism, poverty and development (p. 216). Routledge, New York.

- Hughes, E & Scheyvens, R, 2016. Corporate social responsibility in tourism post-2015: A development first approach. Tourism Geographies 18(5), 469–82. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2016.1208678

- Kaplinsky, R & Morris, M, 2000. A handbook for value chain research (p. 113). IDRC, Ottawa.

- Kauppila, P, Saarinen, J & Leinonen, R, 2009. Sustainable tourism planning and regional development in peripheries: A Nordic view. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 9(4), 424–35. doi: 10.1080/15022250903175274

- Kirsten, M & Rogerson, CM, 2002. Tourism, business linkages and small enterprise development in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 19(1), 29–59. doi: 10.1080/03768350220123882

- Korutaro, B, Ahebwa, W & Katongole, C, 2013. Provision of services for “a value chain analysis of the Ugandan tourism sector”. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Kampala.

- Meyer, D, 2007. Pro-poor tourism: From leakages to linkages. A conceptual framework for creating linkages between the accommodation sector and ‘poor’ neighbouring communities. Current Issues in Tourism 10(6), 558–83. doi: 10.2167/cit313.0

- Meyer, D, 2009. Pro-poor tourism: Is there actually much rhetoric? And, if so, whose? Tourism Recreation Research 34(2), 197–9. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2009.11081591

- Meyer, D & Goodwin, H, 2006. Caribbean tourism, local sourcing and enterprise development: Review of the literature. Pro-Poor Tourism Partnership, working paper 18.

- Ministry of Tourism, 2013. Uganda Vision 2040: Accelerating Uganda’s Socioeconomic Transformation. Report of Ministry of Tourism.

- Mitchell, J, 2012. Value chain approaches to assessing the impact of tourism on low-income households in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 457–75. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2012.663378

- Mitchell, J & Ashley, C, 2006. Can tourism help reduce poverty in Africa? ODI Briefing Paper (March 2006).

- Mitchell, J & Ashley, C, 2010. Tourism and poverty reduction: Pathways to prosperity. Earthscan, London, UK.

- Mitchell, J & Faal, J, 2008. The Gambian tourist value chain and prospects for pro-poor tourism (p. 68).

- Mitchell, J, Font, X & Li, S, 2015. What is the impact of hotels on local economic development? Applying value chain analysis to individual businesses. Anatolia 26(3), 347–58. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2014.947299

- Niewiadomski, P, 2013. The globalisation of the hotel industry and the variety of emerging capitalisms in Central and Eastern Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies 18, 1–22.

- Nyaupane, GP & Poudel, S, 2011. Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 38(4), 1344–66. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.006

- Pillay, M & Rogerson, CM, 2013. Agriculture-tourism linkages and pro-poor impacts: The accommodation sector of urban coastal KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Applied Geography 36, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.005

- Porter, M, 1980. Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and companies. Free Press, New York.

- Porter, ME & Kramer, MR, 2011. Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review 89(1/2), 62–77.

- Porter, ME & Kramer, MR, 2002. The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review 80(9), 56–69.

- Robinson, S, Seaf, S & Kantor, L, 1998. The case of outsourcing partnerships: Branding and repositioning food and beverages. Arthur Anderson Hospitality and Leisure Executive Report. Arthur Anderson, New York.

- Rogerson, C, 2012. Tourism – agriculture linkages in rural South Africa: Evidence from the accommodation sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 477–95. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.617825

- Romero, I & Tejada, P, 2011. A multi-level approach to the study of production chains in the tourism sector. Tourism Management 32(2), 297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.02.006

- Saarinen, J, 2014. Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability 6(1), 1–17. doi: 10.3390/su6010001

- Scheyvens, R, 2011. Tourism and poverty. Routledge, New York.

- Scheyvens, R, Banks, G & Hughes, E, 2016. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustainable Development 24(6), 371–82. doi: 10.1002/sd.1623

- Singh, E, 2012. Linkages between tourism and agriculture in South Pacific SIDS: The case of Niue. Doctoral Dissertation. New Zealand Tourism Research Institute.

- Snyman, S, 2014. The impact of ecotourism employment on rural household incomes and social welfare in six southern African countries. Tourism and Hospitality Research 14(1-2), 37–52. doi: 10.1177/1467358414529435

- Spenceley, A & Meyer, D, 2012. Tourism and poverty reduction: Theory and practice in less economically developed countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 297–317. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2012.668909

- Thomas-Francois, K, Von Massow, M & Joppe, M, 2017. Strengthening farmers–hotel supply chain relationships: A service management approach. Tourism Planning & Development 14, 198–219. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2016.1204359

- Torres, R, 2003. Linkages between tourism and agriculture in Mexico. Annals of Tourism Research 30(3), 546–66. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00103-2

- UBOS, 2013. 2013 Statistical Abstract (p. 264).

- Vanneste, D & Cabus, P, 2007. Networks of firms in Flanders (Belgium): Characteristics and territorial impacts. In Pellenbarg, P & Wever, E (Eds.), International business geography case studies of corporate firms. Routledge, New York.