ABSTRACT

Urban agriculture has long been endorsed as a means to promote food security and economic wellbeing in African cities. However, the South African context presents mixed results. In order to establish the contributions of urban agriculture to sustainable livelihoods, the sustainable livelihoods framework is applied to a case study on cultivators from Cape Town’s Cape Flats. This study contributes to the empirical literature on urban agriculture by providing a deeper understanding of the benefits cultivators themselves attribute to urban agriculture. The key finding is that cultivators use urban agriculture in highly complex ways to build sustainable livelihoods. NGOs are central to this process. Distrust, crime and a lack of resources are, however, limiting factors. The paper concludes with policy recommendations to support pro-poor urban agriculture in African urban centres.

1. Introduction

Urban agriculture may well provide an income, but this benefit is rarely accessible to the ‘poorest of the poor’. Economically viable urban agriculture requires substantial start-up capital and takes years to realise returns (Reuther & Dewar, Citation2005), which is why urban agriculture’s profitability tends to be directly proportional to the wealth and education of the cultivator (Frayne et al., Citation2016; Rezai et al., Citation2016). This observation has led some to conclude that urban agriculture projects are a waste of development funding (Battersby, Citation2012).

This conclusion is however confounded by a handful of case studies that reveal the considerable empowerment potential of urban agriculture. For example, in the slums of Kibera, Kenya, cultivators built social networks amongst themselves, thereby increasing their access to goods and services (Gallaher, Citation2017). In Botswana, women in a patriarchal context increased their social standing by running their own chicken-farming businesses (Hovorka, Citation2006). These case studies suggest that urban agriculture presents a range of benefits beyond mere economic gains.

By focusing on the economic benefits of urban agriculture, the main body of scholarship has overlooked the complex ways in which urban agriculture empowers economically marginalised people (Slater, Citation2001; Gallaher, Citation2017). Economic gains may not be the sole, or even the primary, benefit of urban agriculture in Africa. The present paper aims to contribute a deeper understanding of the benefits cultivators themselves attribute to urban agriculture by asking ‘What are urban agriculture’s key contributions to livelihoods on Cape Town’s Cape Flats?’

To address this question, a brief review of the literature on urban agriculture in Africa begins the paper, summarising academic discourse on the subject. Thereafter, the sustainable livelihoods framework is outlined to provide a conceptual framework by which to analyse the findings. Based on this analysis, the paper concludes that cultivators in Cape Town value urban agriculture holistically and by no means prioritise profit maximisation. Some of the key benefits cultivators attribute do not even relate to their own wellbeing, rather they seek to uplift their communities and care for the natural environment. The results suggest that urban agriculture’s benefits for the economically marginalised in African cities are broader and more complex than previous studies on economic efficiency and food security suggest, but caution that such benefits are only possible with considerable material support and long-term training, as provided by the NGOs operating in this sector.

2. Diverse perspectives in the literature

Research on urban agriculture in Africa originated with the idea that traditional farming methods could provide food and incomes for resource-constrained urban households (Niñez, Citation1985). This idea gained a broad following, with numerous literature reviews arguing in favour of urban agriculture’s economic and food security benefits (Mougeot, Citation2006; FAO, Citation2012; Poulsen et al., Citation2015). While this assumption was critiqued by some, such arguments were overwhelmed by the sheer volume of material promoting urban agriculture as the solution to African food insecurity (Webb, Citation2011). This assumption is even adopted by the public sector and influences national and municipal policies (City of Cape Town, Citation2007; Taylor, Citation2013; Pereira & Drimie, Citation2016).

In many cases, urban agriculture fails the urban poor (Webb, Citation2011). For example, the poorer and less educated a cultivator is, the less benefit they tend to derive from cultivation, in terms of production volumes, food security and income (Rezai et al., Citation2016). Thus, urban agriculture is unlikely to benefit those who are already marginalised (Frayne et al., Citation2014). However, a handful of case studies suggest the opposite.

Gallaher (Citation2017:180), on ‘sack gardeners’ in the Nakuru slums, Kenya; Hovorka (Citation2005, Citation2006) on chicken farmers in Gaborone, Botswana; and Slater (Citation2001:642) on ‘food gardening’ in Cape Town, South Africa, all demonstrate that economically marginalised women can become financially, socially and politically empowered as a direct result of urban agriculture. The paradoxical results between some case studies finding that urban agriculture is empowering, and others arguing that it only makes the rich richer suggest an intervening variable has not been considered. NGOs appear to be one such variable.

In each of the success stories related above, NGOs were present that invested considerable time and resources into training cultivators and integrating them into supportive networks. When such support is absent, profiteers can exploit the economically vulnerable cultivators, leading to clientelism, debt traps and usury practices (Vervisch et al., Citation2013). Empowering economically marginalised cultivators therefore requires high quality external support that focuses on livelihood sustainability through skills training, social networking and input subsidisation (Banks & Hulme, Citation2012). Evaluating the diversity of livelihood asset bases, and thereby gaining an indication of livelihood sustainability, is made possible through the sustainable livelihoods framework.

3. The sustainable livelihoods framework

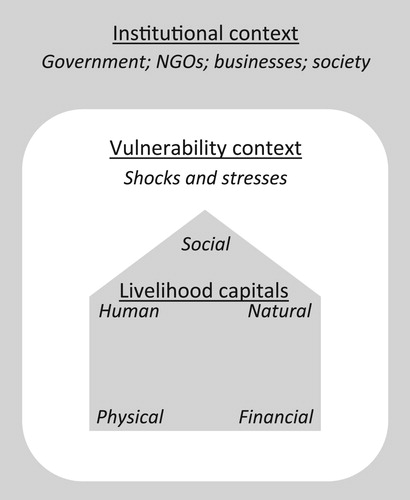

According to Farrington et al’s (Citation1999) interpretation of the sustainable livelihoods framework, five capitals contribute to livelihood sustainability. These are social capital, natural capital, financial capital, physical capital and human capital (). By means of these capitals, an individual is empowered to engage with, benefit from and contribute to society and the natural environment (Bebbington, Citation1999; Morse & McNamara, Citation2013).

Social capital refers to the ‘[f]eatures of social organisation, such as trust, norms and networks that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions’ (Putnam, Citation1993:167). Social capital is particularly important in resource-constrained communities because it provides the foundational trust that is necessary for building networks of reciprocity (Department for International Development, Citation1999). Economically poor households draw on these networks during times of scarcity, and by sharing resources increase the resilience of each household (Woolcock & Narayan, Citation2000; Gallaher, Citation2017).

Natural capital includes natural resources, goods and services (Farrington et al., Citation2002). In Cape Town, open ground is an example of a natural resource that some cultivators utilise. An example of a natural good is the Cape Flats aquifer, a body of water a few metres below ground level (Brodie, Citation2015). Natural services include the myriad flora and fauna that contribute to soil health and prey on the insects that destroy crops. While natural capital may be abundant, oftentimes accessing it requires a combination of financial, physical and human capital (Malan, Citation2015).

Financial capital is an important aspect of sustainable livelihoods, as it can increase one’s capability for accessing other capitals through purchasing them. Financial capital therefore increases both the quantity of capitals one has access to (with more money one can buy more tools), as well as the quality of these capitals (with more money one can buy better tools). Thus, financial capital can significantly increase livelihood sustainability (Department for International Development, Citation1999).

Tools, infrastructure, buildings and agricultural inputs are all examples of physical capital (Department for International Development, Citation1999; Farrington et al., Citation2002). In much of Africa, inadequate or poor-quality infrastructure considerably curtails the economic viability of agricultural production (Reid & Vogel, Citation2006; Vervisch et al., Citation2013). Thus, without external support, it is usually the poorer cultivators that operate least profitably.

Finally, human capital, or one’s skills, education and physical health, play a vital role in livelihood resilience by empowering one to harness natural capitals and expanding opportunities for earning an income (Jacobs, Citation2009; Chirau, Citation2012). Thus, human capital is the cornerstone of livelihood sustainability.

Livelihood sustainability is influenced by external factors such as the political and vulnerability context. The vulnerability context includes stresses and shocks such as a slow decline in annual rainfall or eviction, respectively (Reid & Vogel, Citation2006). The institutional context includes role-players such as government, NGOs and private sector funders (Department for International Development, Citation1999). A supportive institutional context can significantly increase one’s ability to recover from stresses or shocks (Reid & Vogel, Citation2006). NGOs tend to be the most instrumental role-players helping cultivators to overcome economic and socio-political limitations (Slater, Citation2001; Hovorka, Citation2005, Citation2006; Gallaher, Citation2017).

The sustainable livelihoods framework has been referred to, with a hint of cynicism, as a ‘checklist’ of possible elements making up a livelihood (Scoones, Citation2009). ‘Checklist’ implies a lack of linkages between the five livelihood capitals (Dorward, Citation2014). Furthermore, the capitals themselves are criticised for ignoring ‘key issues such as markets, institutions and politics’ (Dorward, Citation2014). In order to address these weaknesses, the present study will highlight the linkages between the capitals in the concluding discussion. Additionally, the possibility of ignoring relevant issues such as markets or politics is counteracted by the qualitative depth of this study’s data, as demonstrated in the methods section that follows.

4. Research methods

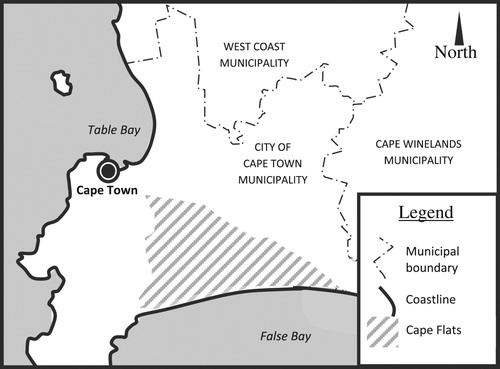

Fieldwork took place on the Cape Flats (), a vast area (630 km2) of council housing and informal shacks resulting from apartheid’s racist town planning (Adelana et al., Citation2010; Brodie, Citation2015). While many Cape Flats residents came to Cape Town seeking work, the unemployment rate is high; on average 29% of working-age adults are unemployed, according to the most recent census results (City of Cape Town, Citation2011).

The social challenges relating to unemployment are being addressed by thousands of NGOs on the Cape Flats (Republic of South Africa, Citation2013) who, along with local and national government departments, promote urban agriculture to improve food security in the area (Battersby & Marshak, Citation2013). External assistance is necessary, as low soil fertility and dry summer winds inhibit the spontaneous adoption of urban agriculture as seen in other African countries (Dyer et al., Citation2015).While many NGOs, such as clinics, crèches and community-based organizations, have a vegetable garden on their premises, extensive desktop research established that only four NGOs actively promoted urban agriculture among households on the Cape Flats by training cultivators and providing ongoing extension services.

These four NGOs differ in term of the size of their membership. The largest had a few thousand members, while the smallest had mere dozens. One of the NGOs tended more towards promoting cultivation groups on common land. A few of these groups belonged to a community-supported agriculture scheme that this NGO administrated. The remaining three NGOs focused on small-scale, individual subsistence cultivation around the home.

The manner in which these four NGOs ran training programmes and provided ongoing support for cultivators was remarkably similar. Key similarities included that all four adopted agro-ecological principles, most notably rejecting petro-chemical inputs. They also encouraged low-tech, small-scale cultivation. Cultivated plots associated with any four of the NGOs would characteristically consist of rows of beds a metre wide, planted with an array of vegetables.

In order to improve community buy-in, each of the NGOs in this study had a base of operations within their target neighbourhood (Poulsen et al., Citation2014). There they sold basic agricultural inputs such as seeds, seedlings and compost to the public. They also stored such inputs, which were complimentary to the training courses for new cultivators. The NGOs made these inputs themselves, or were given them by donors. While the urban agriculture cases in the present study were too small to warrant agricultural loans from government, they received donations of infrastructure and inputs from government, as ratified in the City of Cape Town’s (Citation2007) urban agriculture policy. The NGO running the community-supported agriculture scheme loaned inputs and seedlings to the participating cultivators, who then repaid the loan from their profits.

Fieldwork was prepared for using extensive desktop research and informal discussions with practitioners. In this way, an understanding of the sector was gained that informed the choice of methodology. Following interviews with senior leadership from each of the four NGOs, the researcher was granted access to the records of the four NGOs, which revealed that over 6500 cultivators were being supported on the Cape Flats in 2013 ().

Table 1. NGOs supporting urban agriculture on the Cape Flats in 2013.

At this point, it became clear why previous researchers’ selections of participants had been so limited: traditional methods such as random sampling were impossible. While the contact details of many of these cultivators were available, locating them for interviews was impracticable due to unmarked road networks, informal living arrangements and unpredictable daily routines. Thus, the only viable sampling methods were purposive, as adopted by the vast majority of previous researchers.

The present study combined opportunistic and criterion sampling, which allowed the researcher ‘to take advantage of unforeseen opportunities’, permitting ‘the sample to emerge during fieldwork’ (Patton, Citation1990). Locating cultivators was done with help from the four mentioned NGOs who drew maps, drove the researcher along the extension officers’ routes, provided guides, asked for referrals from locals and in brief utilised all the means by which the extension officers find their way around.

All four NGOs were equally represented. The proportion of cultivators from the largest NGO represented the largest proportion (51%) of the sample. The remaining three represented 25%, 12% and 10% of the sample, respectively, roughly according to the relative size of each NGO’s population of members. The majority of the sample (60%) were women, Xhosa speakers (85%) and over 40 years old (74%). This appears consistent with the profile of the population of cultivators in Cape Town (Tembo & Louw, Citation2013).

To ensure that the sample adequately represented the voices of the Cape Flats cultivators, sampling continued for five months (March to August 2014). A broad selection of cultivators was made, representing many of the areas these NGOs operate in throughout the Cape Flats. Thus, fieldwork took place in Khayelitsha, Lavender Hill, Mitchell’s Plain, Nyanga, Philippi, Mfuleni and Vrygrond.

This study sought to provide qualitative depth regarding the ways in which cultivators use urban agriculture to enhance livelihood sustainability. It did not seek to provide a statistically representative sample. Therefore, in accordance with the principles of qualitative research, data collection continued until no new discussion themes emerged, and until no new information emerged within each theme (Patton, Citation1990). This marked the point of data saturation. Data saturation, not a statistically representative sample size, is qualitative research’s indication of sampling sufficiency (Patton, Citation1990). This was achieved for participants in all four NGOs, confirming that each of the NGOs were sufficiently represented in the present study.

Data collection involved 34 semi-structured in-depth individual interviews and four focus groups. Between four and five cultivators were present at each focus group. The total number of participants from the individual interviews and focus groups equalled 59. The interviews and focus groups were voice recorded and transcribed.

The transcriptions were ordered according to themes relating to the sustainable livelihoods framework. Poignant snippets of these transcriptions are presented in the results below when they provide unexpected or deeper insights into urban agriculture’s contribution to sustainable livelihoods. The individuality of the cultivator quoted is represented by a unique number and an indication of demographics such as gender and age. For example, a young adult female farmer assigned the number 1 would be cited as (F1 ≥ 18)Footnote1. Names are withheld to protect the anonymity of the participants.

5. Results and analysis

Cultivators throughout the Cape Flats found urban agriculture an important livelihood strategy. Considering the variety of cultivators represented in this paper, in terms of gender, age and scale of production, it is notable that a common thread throughout the interviews was a sense of enthusiasm towards this enterprise.

5.1. Social capital

Social capital promotes the smooth operation of society by increasing levels of trust and reciprocity (Putnam, Citation1993). However, social ills like domestic violence, substance abuse and crime can undermine social capital (May & Norton, Citation1997; Slater, Citation2001; Misselhorn, Citation2009; Vervisch et al., Citation2013). According to the cultivators, these social ills are common on the Cape Flats. For example, a female Vrygrond cultivator simply describes these as ‘women’s problems’, stating, ‘On Saturdays in the women’s group, most of the women will cry: My husband is abusing me, […] my child has got a boyfriend, my boy is smoking; and stuff like that’ (F56 ≥ 40).

These social ills have perpetuated through generations, as cultivators recall growing up in abusive homes as children. For example, an elderly Vrygrond woman described life as a child: ‘I was abused by my father, so […] I stayed at my grandmother. She was a woman you don’t stand on, she stands on you. […] She beat me up’ (F5 ≥ 65). For this woman, and many others on the Cape Flats, estrangement from family and domestic violence continue into adulthood.

Abuse continued into this woman’s adult life, at the hand of her husband. Additionally, her children disowned her. Her narrative chokes off as she breaks into tears: ‘It’s like they don’t like me anymore – they don’t let my grandchildren come to me. I gave my daughter what I didn’t have in my life. But I don’t want to talk about that’ (F5 ≥ 65). For many cultivators, close supportive relationships are not found in their biological family.

Poverty also has an isolating effect on individuals. While living conditions in some areas of the Cape Flats may appear disorderly, there is still a strong sense of propriety among many residents. A cultivator from Lavender Hill confirms this, ‘In our area, people are very precise; they are very conservative’ (F18 ≥ 40). This desperation to appear affluent traps many in debt as they buy symbolic artefacts on credit. A mother of seven from Vrygrond explains for example how her two elder sons who work have no money left for their family after paying off the debt on their name-brand shoes and cell phones: ‘They want the name brands; like, they will make a lay-by for the name brands. They don’t want to hear about Pep Stores’ (F1 ≥ 40).

For this woman and many like her who experience long seasons of unemployment, the shame of poverty cuts them off from society. Thus, in an environment where people will bankrupt themselves to appear affluent, or where family members are habitually violent towards each other, social capital is desperately needed.

Cultivators provided many examples of how social capital plugs them into caring relationships and reconnects them to society. Every cultivator that was interviewed provided some example of how they built meaningful relationships as a direct result of urban agriculture. For some, this manifests as time spent and gifts exchanged with biological family. Examples included parents spending time in the garden with their children; adult children exchanging seedlings or preparing harvested produce with their parents; and migrant family members calling home to ask advice on gardening from siblings or parents.

For others, ‘family’ became those with whom they cultivate. One Mfuleni woman shares a common sentiment, namely that her cultivation group is ‘like one family’ as they ‘share everything’ (F7 ≥ 18). This included groups of mixed gender and age. A profound level of mutual respect existed between all group members. Thus, urban agriculture creates bonding capital within families as well as actually creating new ‘families’, which is particularly important for those cultivators whose biological families are non-existent or dysfunctional.

For many, urban agriculture simply provided the self-confidence cultivators need to re-engage with their community. For the vast majority of cultivators, it is both the activity of doing urban agriculture and the accomplishment of producing a crop that allows them to hold their head up in society. Moreover, it is the potential to contribute meaningfully to their community that engenders a sense of self-worth. For example, in Vrygrond, where there is a mix of council housing and informal dwellings, plot sizes can vary. One cultivator with a relatively larger plot sees it as her duty to use the space she has to grow food for her neighbours living in shacks:

Everyone across from me in shacks have so little space that they can't garden. I usually call some of their children to come and assist me in the garden. And usually, when I take out some of the veggies, I call them to come and fetch it and I say they can take it out of the garden and I’m going to give it to your mother. The children get quite excited about that.

The shame resulting from poverty, as well as low levels of formal education, hinder cultivators from engaging meaningfully with government or brokering business deals on the formal market (Vervisch et al., Citation2013). As one of the NGO representatives explains, ‘There’s a whole lot of shaping, educating [and] mentoring that has to happen’ before such people have the confidence and skills to deal with powerful role-players directly. Cultivators confirmed this, and related failed attempts to deal directly with local government. For example, one young man who wanted to request permission to farm vacant land in Nkanini, Khayelitsha remained unable to meet the official in charge, even after numerous trips to the relevant offices:

I interacted with her office, but I was not fortunate in terms of, like, having to talk with her. Each and every time they were referring me to her assistants, which doesn’t help because […] they don’t have the powers […]. We were then giving up on that land (M20 ≥ 18).

5.2. Human capital

Urban agriculture case studies throughout Africa record agricultural experience as a key contributor to a cultivator’s success (FAO, Citation2012). In Cape Town however, this is rarely true. Some cultivators in this study were born in urban townships and had no interest in agriculture as youngsters: ‘I was a township girl, I’m not from the country. […] So what am I going to do with chickens and cows and that sort of stuff?’ (F17 ≥ 65). Others who were born in rural areas found rural methods useless in Cape Town, where the conditions are vastly different: ‘I know about [agriculture], but from the Eastern Cape – in the soil, not the sand’ (M33 ≥ 65). Thus, unlike elsewhere in Africa, rural farming experience is of no notable advantage for Cape Town’s urban cultivators. Success in urban agriculture on the Cape Flats is primarily the result of the high quality training provided by the NGOs in this study.

In addition to receiving formal urban agriculture training, cultivators informally network among themselves. Through these networks, they reinforce what they know, or communicate new lessons they have learned through experience. Some have even begun self-studying to accelerate the learning process. One young man from Khayelitsha expresses his enthusiasm for gaining knowledge: ‘I am a man that wants to learn more so that I can improve my mind and share what I have with other people’ (M14 ≥ 18). Knowledge increases farming expertise, but it also promotes self-esteem, as cultivators are able to share their expertise with their fellows and the surrounding community.

In addition to gains in skills and self-confidence, human capital extends to physical health. On the Cape Flats, residents tend to consume highly processed foods of a low nutritional value (Battersby, Citation2012). The cultivators in the present study believed that urban agriculture not only increased their access to fresh produce, but also changed their attitude towards healthy eating. A Khayelitsha man explained that practicing urban agriculture made him ‘become conscious of what I eat; what I put in my mouth and what I buy’ (M14 ≥ 18). Cultivators feel a sense of duty towards educating those around them to eat healthily too. They explained that in their areas, ‘there are high levels of people that are diabetic. And many other chronic diseases that can be treated if you eat properly; [if you] eat food that is not artificial’ (M14 ≥ 18). Thus, even if a relatively low volume of food is grown, the experience of growing it inspires people to make healthy choices about the food they purchase.

5.3. Financial capital

In urban areas, access to food and other necessities is only possible through cash-based transactions (Farrington et al., Citation2002:19). Thus, the flows of income urban agriculture generates remain a key focus of research in Africa (Battersby & Marshak, Citation2013).

Much of the existing research on urban agriculture in Africa argues that the financial gains from urban agriculture are twofold: one, cultivators are saving money that they no longer need to spend on food; and two, surplus produce may be sold or bartered (Maxwell, Citation1994). While commercialisation of urban agriculture is prevalent in a number of African cities such as Accra, Dakar and Kinshasa (FAO, Citation2012), the same cannot be said for Cape Town.

In Cape Town, only 120 cultivators generate a substantial portion of their income from urban agriculture (Abalimi newsletter Citation42, Citation2015), while the several thousand remaining cultivators are primarily subsistence cultivators. While this has lead to criticism of Cape Town’s urban agriculture sector (Battersby, Citation2012), the contribution urban agriculture makes to household finances is in fact far more complex.

The distinction between ‘commercial’ and ‘subsistence’ cultivators is not at all clear. So-called subsistence cultivators operating at a relatively small scale actually benefit financially in a number of ways. For some, the plot serves as an investment strategy. In many resource-constrained communities, distributing resources, particularly among family members, is common practice. While this creates an informal social safety net that allows family members to ‘get by’ during tough times (Woolcock & Narayan, Citation2000:227), the negative impact is that attempts to save money could be seen as selfish (Portes, Citation1998).

Urban agriculture allows cultivators to ‘save’ money by investing it into a cultivated plot, and then ‘cashing-in’ as needed by selling produce. This may be done in small amounts, more frequently, to make it through the last lean week of the month, or it can provide a lump sum if a season’s crop is sold at once. A man from Lavender Hill explained that after selling his season’s crop, he immediately used the profit to replace broken appliances and to buy non-perishable food in bulk. When he came home, his wife asked, ‘Where did you get all this money from?’ To which he responded, ‘I got it from the yard’ (M8 ≥ 40). While this once-off sale may not have contributed much to his annual budget, it nevertheless enabled him to access extra cash when it was needed, rather than being forced to buy on credit.

Urban agriculture’s financial benefits extend beyond the provision of cash. For example, it is common practice for cultivators to barter their produce for pre-paid electricity vouchers, paraffin fuel, teabags, coffee and sugar. One Lavender Hill cultivator explains, ‘If I don’t have electricity, I ask my neighbour – or bread – […] you know how it goes. So I can give them something from my garden’ (M8 ≥ 40). In so doing, cultivators are not only gaining valuable goods in exchange for surplus produce, but are also strengthening social capital, which may increase their eligibility for asking favours even when they do not have commodities to exchange directly.

While attention has been paid to the financial viability of urban agriculture as a career (Reuther & Dewar, Citation2005), the non-financial exchanges the present paper highlights have been overlooked. The economic benefits of such exchanges may appear insignificant in relation to a cultivator’s annual cash income, but the role these exchanges play in stabilising household cash flows is incredibly important.

5.4. Natural and physical capital

Physical capital, such as tools, machinery and infrastructure, is often a prerequisite for utilising natural capital. A good example is the aquifer a few metres below ground level throughout the Cape Flats (Adelana et al., Citation2010). With the right equipment, this resource is freely available, but resource-constrained households do not have the means to capitalise on this natural good. The expense of gaining reliable, safe access to natural goods is a major hindrance for low-income cultivators. A considerable investment of equipment and education is therefore necessary for cultivators on the Cape Flats to benefit from the natural goods and services that surround them.

A large part of the training cultivators received from the NGOs in this study dealt with harnessing natural capital. All of the NGOs in this study trained cultivators to encourage biodiversity in the garden for pest control, to mulch to retain soil moisture, as well as to make compost to stimulate microbial health in the soil. Donations of physical capital, such as hand tools, also facilitated this work. Larger cultivation groups were eligible to receive more substantial donations from local government, such as borehole installations, perimeter fencing and storage containers (Small, Citation2002).

The cultivators who were trained by these NGOs increased their self-determination and livelihood sustainability as they became increasingly capable of harnessing natural goods and services. As these cultivators became more established, they became less reliant on donations of inputs. This is because they were able to prepare in advance for an upcoming season. They did this by germinating the seeds they harvested from the previous season; by fertilising their soil with their own compost; and by mulching with material that they collected.

Through being taught these basic agro-ecological principles, cultivators gained a deep appreciation for the natural world. For example, one young female cultivator referred to global climate change as ‘a wakeup call’, adding that she ‘would not be happy to be one of those people that are adding to global warming and climate change’ (F16 ≥ 18). Even among small children at a Vrygrond pre-school, a respect for the earth was cultivated through including urban agriculture in the curriculum. The preschool teacher related that pupils tell their parents ‘they must not litter [because] they don’t like [having] plastic bags around’ (F56 ≥ 40). Being trained to value natural goods and services, and to steward them wisely, carries with it not only the benefit of increasing the sustainability of cultivators’ livelihoods, but creates spin-off benefits in which children and adults begin to understand why it is important to look after the natural capital around them.

5.5. Limitations to urban agriculture

This paper focused primarily on the benefits of urban agriculture. It was therefore beyond the scope of the paper to address in any detail the possible negative influences that urban agriculture and its role-players may have had on sustainable livelihoods. There were however a number of challenges cultivators faced. The most commonly mentioned challenges are related below.

The present study found that adverse living conditions inhibit cultivation. For example, an elderly lady from Vrygrond who had joined an urban agriculture training course experienced a major setback as the result of being mugged. She recalls, ‘Last year I had all the veggies you could think of. But then I was mugged and got sick and didn’t have my phone [anymore] and […] [so they] couldn’t phone me. But I thank God I’m alive again’ (F5 ≥ 65). This case illustrates how shocks can severely undermine livelihood sustainability.

Crime was so common for the cultivators that many selected what they cultivated on the likelihood of it being stolen. For example, fruit cultivation is uncommon on the Cape Flats because, ‘these boys, they jump over the fence to get them’ (M35 ≥ 40), but vegetables are common, as ‘they will never climb over a fence to steal a cabbage’ (M26 ≥ 18). The same applies to poultry farming, which has proven lucrative for urban cultivators in other countries (Hovorka, Citation2006). An NGO representative explained however that ‘the moment you put your chickens out […] or have fruit, then people will climb fences to get it’. Thus, through lost opportunities, personal trauma and stolen implements, crime limits urban agriculture’s potential contributions to sustainable livelihoods on the Cape Flats.

Group cultivation is encouraged by the City of Cape Town (City of Cape Town, Citation2007), as well as by the largest of the four NGOs. Some reasons for this include that it can be a more efficient use of resources. However, in practice, these groups can be fraught with ‘internal rivalries, all beautifully covered over’, as an NGO representative described it. Thus, one of the NGOs that was interviewed discontinued with cultivation groups altogether and focused solely on home cultivators. Nevertheless, the well established groups exhibited a good work ethic among the cultivators, the complete absence of hierarchy, democratic decision-making about and transparency when handling money and a habit of sharing meals made from their garden. Such examples show that group cohesion is possible, but it tends to characterise the groups that have been operating for a number of years.

These limitations were the most often repeated hindrances to urban agriculture in the present study. This paper wishes to draw attention to these challenges in order to avoid misrepresenting urban agriculture as a panacea to African urban poverty.

6. Conclusions

This paper set out to answer the question, ‘What are urban agriculture’s key contributions to livelihoods on the Cape Flats?’ In addressing this question, the paper argued that cultivators use urban agriculture in far more complex ways than the body of scholarship suggests. Empirical research on urban agriculture in Africa tends to treat specific aspects of urban agriculture such as its economic viability, its contribution to food security or its social and psychological benefits, in isolation. By applying the sustainable livelihoods framework, the present study incorporates all of these benefits, and moreover, shows that these benefits are deeply interrelated. The key contribution of the present paper is therefore to demonstrate that urban agriculture at any scale of operation can contribute to livelihood sustainability.

Based on the findings, some important lessons may be drawn from Cape Town’s case.

Firstly: The social capital gains that urban agriculture facilitates have direct economic payoffs. For example, cultivators share their surplus goods, thereby indebting their neighbours with an obligation to reciprocate. This increases the likelihood that cultivators receive goods or services from their neighbours in times of need. Even small-scale, ‘subsistence’ cultivation therefore has the potential to provide an inclusive economic benefit.

Secondly: Urban agriculture training is the ideal vehicle for educating people to live healthy lifestyles and care for their natural environment. Thus, cultivators that operate at a small scale, who may not gain any significant food security benefits in a quantitative sense, nevertheless begin to appreciate the value of healthy eating in general. Equally, although a small plot may have no significant ecological benefits, cultivators understand how their everyday choices impact the natural environment.

Thirdly: Urban agriculture is not necessarily empowering for the economically marginalised because resource limitations constrain their capability to harness natural resources. Physical capital such as tools and infrastructure, as well as human capital gains from training, are therefore prerequisites to accessing natural capital (Malan, Citation2015). External support, such as from NGOs, is instrumental in this regard.

Finally: Crime and interpersonal conflict may present some of the greatest limitations to urban agriculture in economically marginalised neighbourhoods. Thus, donations of material inputs and training alone are insufficient for launching an urban agriculture enterprise. If urban agriculture is to play a role in community development, its sustainability requires adequate security as well as long-term support.

The lessons learned from this case are relevant wherever urban agriculture is promoted as a pro-poor development strategy. An urban agriculture sector in which success is defined as profit maximisation marginalises those who have few resources, little formal education and a low social status. The sustainable livelihoods framework shows that all five livelihood capitals are important, and developing these through urban agriculture can contribute to improving livelihood sustainability. Nevertheless, doing so takes time and effort, and usually requires assistance from an external actor such as an NGO. With appropriate institutional support, much potential exists for building sustainable livelihoods by promoting urban agriculture on the Cape Flats, as well as in other African urban centres.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Abalimi, Inity, Soil for Life and the Sozo Foundation, along with the cultivators affiliated with them, for the time and insights they gave to this research. This research was supported by a grant from Stellenbosch University’s Hope Project, through the Food Security Initiative. I would also like to thank the Africa Climate Change Adaptation Initiative (ACCAI) Network and the Open Society Foundation for supporting his fellowship at the Global Change Institute.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

David W Olivier http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6037-9150

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Three age ranges are used: ≥18 (18 to 39), ≥40 (40 to 64) and ≥65.

References

- Abalimi newsletter 42, 2015. http://www.abalimi.org.za/newsletters/nl42.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2017.

- Adelana, S, Xu, Y & Vrbka, P, 2010. A conceptual model for the development and management of the Cape Flats aquifer, South Africa. Water SA 36(4), 461–474. doi: 10.4314/wsa.v36i4.58423

- Banks, N & Hulme, D, 2012. The role of NGOs and civil society in development and poverty reduction. Working paper No. 171. Brooks World Poverty Institute: Manchester.

- Battersby, J & Marshak, M, 2013. Growing communities: Integrating the social and economic benefits of urban agriculture in Cape Town. Urban Forum 24(4), 447–61. doi: 10.1007/s12132-013-9193-1

- Battersby, J, 2012. Urban food security and climate change: A system of flows. In Frayne, B, Moser, C & Ziervogel, G (Eds.), Climate change, assets and food security in Southern African cities. Routledge, London, 35–56.

- Bebbington, AJ, 1999. Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development 27(12), 2021–44. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00104-7

- Brodie, N, 2015. The Cape Town Book. Struik, Cape Town.

- Chirau, TJ, 2012. Understanding livelihood strategies of urban women traders: A case of Magaba, Harare in Zimbabwe. Master’s thesis, Rhodes University, South Africa.

- City of Cape Town, 2007. Urban agriculture policy for the City of Cape Town. Government Printer, Cape Town.

- City of Cape Town, 2011. Census – cape flats planning district. https://www.capetown.gov.za/en/stats/2011%20Census%20%20Planning%20District%20Profiles/Cape%20Flats%20Planning%20District.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2016.

- Department for International Development, 1999. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. DFID, London.

- Dorward, AR, 2014 . Livelisystems: a conceptual framework integrating social, ecosystem, development, and evolutionary theory. Ecology and Society. https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol19/iss2/art44/. Accessed 29 January 2018.

- Dyer, M, Mills, R, Conradie, B & Piesse, J, 2015. Harvest of Hope: The contribution of peri-urban agriculture in South African townships. Agrekon 54, 73-86. doi: 10.1080/03031853.2015.1116400

- FAO, 2012. Growing greener cities in Africa: First status report on urban and peri-urban horticulture in Africa. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Farrington, J, Carney, D, Ashley, C & Turton, C, 1999. Sustainable livelihoods in practice: Early applications of concepts in rural areas. Working Paper No. 42. Overseas Development Institute, London.

- Farrington, J, Ramasut, T & Walker, J, 2002. Sustainable livelihoods approaches in urban areas: General lessons, with illustrations from Indian cases. Working Paper No. 162. Overseas Development Institute, London.

- Frayne, B, McCordic, C & Shilomboleni, H, 2014. Growing out of poverty: Does urban agriculture contribute to household food security in Southern African cities? Urban Forum 25(2), 177–89. doi: 10.1007/s12132-014-9219-3

- Frayne, B, McCordic, C & Shilomboleni, H, 2016. The mythology of urban agriculture. In Crush, J & Battersby, J (Eds.), Rapid urbanisation, urban food deserts and food security in Africa. Springer, Waterloo, 19–31.

- Gallaher, CM, 2017. Regreening Kibera: How urban agriculture changed the physical and social environment of a large slum in Kenya. In WinklerPrins, AMGA (Ed.), Global urban agriculture. CABI, Oxfordshire and Boston, 171–83.

- Hovorka, AJ, 2005. The (re)production of gendered positionality in Botswana's commercial urban agriculture sector. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95(2), 294–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00461.x

- Hovorka, AJ, 2006. The no. 1 ladies’ poultry farm: A feminist political ecology of urban agriculture in Botswana. Gender, Place and Culture 13(3), 207–25. doi: 10.1080/09663690600700956

- Jacobs, C, 2009. The role of social capital in the creation of sustainable livelihoods: A case study of the Siyazama Community Allotment Gardening Association (SCAGA). Master’s thesis, Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

- Malan, N, 2015. Urban farmers and urban agriculture in Johannesburg: Responding to the food resilience strategy. Agrekon 54(2), 51–75. doi: 10.1080/03031853.2015.1072997

- Maxwell, DG, 1994. The household logic of urban farming in Kampala. In Egziabher, AG, Lee-Smith, D, Maxwell, DG, Memon, PA, Mougeot, LJA & Sawio, CJ (Eds.), Cities feeding people: An examination of urban agriculture in East Africa. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, 47–66.

- May, J & Norton, A, 1997. ‘A difficult life’: The perceptions and experience of poverty in South Africa. Social Indicators Research 41(1), 95–118.

- Misselhorn, A, 2009. Is a focus on social capital useful in considering food security interventions? Insights from KwaZulu–Natal. Development Southern Africa 26(2), 189–208. doi: 10.1080/03768350902899454

- Morse, S & McNamara, N, 2013. Sustainable livelihood approach. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Mougeot, LJA, 2006. Growing better cities: Urban agriculture for sustainable development. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa.

- Niñez, V, 1985. Introduction: Household gardens and small–scale food production. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 7(3), 1–5.

- Patton, MQ, 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Pereira, L & Drimie, S, 2016. Governance arrangements for the future food system: Addressing complexity in South Africa. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 58(4), 18–31.

- Portes, A, 1998. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24, 1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Poulsen, MN, Hulland, KRS, Gulas, CA, Pham, H, Dalglish, SL, Wilkinson, RK & Winch PJ, 2014. Growing an urban oasis: A qualitative study of the perceived benefits of community gardening in Baltimore, Maryland. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 36(2), 69–82. doi: 10.1111/cuag.12035

- Poulsen, MN, McNab, PR, Clayton, ML & Neff, RA, 2015. A systematic review of urban agriculture and food security impacts in low-income countries. Food Policy 55, 131–146. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.07.002

- Putnam, RD, 1993. Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

- Reid, P & Vogel, C, 2006. Living and responding to multiple stressors in South Africa–Glimpses from KwaZulu-Natal. Global Environmental Change 16, 195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.01.003

- Republic of South Africa, 2013. Registered NPOs in the Western Cape. http://www.dsd.gov.za/npo/index.php?option=com_docmanandtask=doc_detailsandgid=168andItemid=39 Accessed 21 May 2014.

- Reuther, S & Dewar, N, 2006. Competition for the use of public open space in low-income urban areas: The economic potential of urban gardening in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. Development Southern Africa 23(1), 97–122. doi: 10.1080/03768350600556273

- Rezai, G, Shamsudin, MN, Mohamed Z, 2016. Urban agriculture: A way forward to food and nutrition security in Malaysia. Procedia 216, 39–45.

- Scoones, I, 2009. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1), 171–196. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820503

- Slater, R, 2001. Urban agriculture, gender and empowerment: An alternative view. Development Southern Africa 18(5), 635–50. doi: 10.1080/03768350120097478

- Small, RA, 2002. Lessons from the Cape Flats townships: Ecological micro-farming among the poor in Cape Town. Urban Agriculture Magazine 6, 30–31.

- Taylor, SJ, 2013. The 2008 Food Summit: A political response to the food price crisis in Gauteng province, South Africa. Development Southern Africa 30(6), 760–70. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.860015

- Tembo, R & Louw J, 2013. Conceptualising and implementing two community gardening projects on the Cape Flats, Cape Town. Development Southern Africa 30(2), 224–37. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.797220

- Vervisch, TGA, Vlassenroot, K & Braekman, J, 2013. Livelihoods, power, and food security: Adaptation of social capital portfolios in protracted crises–case study Burundi. Disasters 37(2), 267–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2012.01301.x

- Webb, NL, 2011. When is enough, enough? Advocacy, evidence and criticism in the field of urban agriculture in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 28(2), 195–208. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2011.570067

- Woolcock, M & Narayan, D, 2000. Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. The World Bank Research Observer 15(2), 225–49. doi: 10.1093/wbro/15.2.225