ABSTRACT

Poor living conditions are a consequence of the history of the South African mining industry (SAMI), despite legislation having been implemented to attempt to address this challenge. This paper describes the living conditions of mine workers from eight mines in South Africa in 2014, and assesses changes made over the previous decade. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected at three platinum, two gold, one coal, one diamond, and one manganese mine in 53 interviews with mine management, 11 interviews with labour representatives, 14 focus groups with mine workers, and 875 questionnaires completed by mine workers. The use of single-sex hostels and hostel room occupancy rates has reduced, while the use of living-out allowances (LOAs) has increased. Problems included the high proportions of informal accommodation; a lack of access to water, sanitation, and electricity; and poor roads. While improvements to the living conditions in the SAMI are evident, challenges still remain.

1. Introduction

The workforce of the South African mining industry (SAMI) was traditionally housed in single-sex mining compounds or hostels from the late 1800s (Marais & Venter, Citation2006; Republic of South Africa, Citation2009b). Migrant labourers were employed in the mining industry, and African men had to leave their families in rural parts of South and southern Africa and travel to mining centres, where they lived in these hostels while working at the mines (Bezuidenhout & Buhlungu, Citation2011). The housing and living conditions for many workers in this industry were sub-standard, which had adverse effects on their health, productivity, and social wellbeing (Republic of South Africa, Citation2009b). Organised labour played a role in driving new housing policies and legislation, with campaigns against migrant labour and the hostel system (Bezuidenhout & Buhlungu, Citation2011). Mining firms formally abandoned the preference for hostel accommodation in 1986 (Bezuidenhout & Buhlungu, Citation2011).

A consequence of the history of the SAMI is that most South African mining towns maintain poor social and economic conditions, such as poverty, unemployment, bad housing and infrastructure, prostitution, poor health, and a high influx of single migrant labourers (Cronjé & Chenga, Citation2009). Housing currently available to mine workers, in addition to conventional hostels, includes limited married quarters, Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) houses, mine workers’ own houses in new suburbs, township houses, informal settlements, villages near mines, flats rented from companies, and backrooms (Bezuidenhout & Buhlungu, Citation2011). Mines commonly offer living-out allowances (LOAs) to employees in order to subsidise employees’ accommodation. However, some employees set up minimal housing in informal settlements around the mine, in order to save a portion of the LOA to send to their rural homes.

Policies and legislation relating to the living conditions in the SAMI have been implemented with the aim to improve the housing of mine workers (e.g. Republic of South Africa, Citation1996a, Citation1996b, Citation1997, Citation2002a, Citation2002b, Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2009c, Citation2010). The Mining Charter and its amendment (Republic of South Africa, Citation2002a, Citation2008b) compelled mining companies to ‘convert or upgrade hostels into family units by 2014’, ‘attain the occupancy rate of one person per room by 2014’, and ‘facilitate home ownership options for all mine employees in consultation with organised labour by 2014’. The Framework Agreement for a Sustainable Mining Industry of 2013 ascertained organised labour, organised business, and governments’ commitment to upgrade human settlements in mining towns (Republic of South Africa, Citation2013).

Policy changes can and have also had unintended consequences on mine worker housing. For example, changes in housing policies can result in urban sprawl and constraints to the delivery of basic services (SACN, Citation2017). Other changes in the industry, including a trend toward shift work and outsourcing or contract work, which is associated with lower salaries and fewer benefits, also have an impact on workers’ living conditions (Bezuidenhout & Buhlungu, Citation2011; SACN, Citation2017; Marais et al., Citation2018). Housing developments in remote mining areas have led to the creation of ‘ghost towns’ in the past, and there is a risk of this in the future due to the limited life of mines, and mine downscaling in terms of employment (Cloete et al., Citation2009; Marais & Nel, Citation2016).

A study conducted by Lewis (Citation2003), regarding housing in the SAMI, revealed that the most common housing arrangements at the time were single-sex hostels and LOAs, which accommodated 46% and 31% of the workforce, respectively. Of the single-sex hostel dwellers, 65% resided in a room with seven to eight occupants, 16% resided in rooms with five to six occupants, and 18% with four or fewer occupants (Lewis, Citation2003). Lewis also found that, of those who stayed in off-mine accommodation, 50% lived in houses or brick structures on their own stands and 41% lived in shacks or backyard dwellings, while the rest stayed in local authority houses, self-built houses on local authority land, in flats, or in rooms in houses. The main problems with the housing of off-mine dwellers were the quality of building materials, bulk basic services (such as water, electricity, and sewerage), violence and insecurity, access to and quality of health services and transport, and the perceived permanence of the housing. The main reported deficits for hostel dwellers were overcrowding, a lack of sleep, rest, and privacy, violence and insecurity, and poor access to services such as schools for their children and private cooking facilities.

A study by Marais & Venter (Citation2006) revealed that 67% of the participating mine workers in the SAMI were unhappy with their housing situations, 15% were satisfied, and 19% were happy. Causes for unhappiness included that they did not own houses and that they did not live with their families.

Poor living conditions are associated with various health and safety outcomes and quality of life (Alnsour & Meaton, Citation2014; Burridge & Ormandy, Citation2007; Galobardes et al., Citation2006; Statistics South Africa, Citation2011; Williams et al., Citation2010). These include the spread of infectious disease or infection, owing to overcrowding or a lack of water or sanitation, and illness and accidents (Galobardes et al., Citation2006; Burridge & Ormandy, Citation2007). They may further have an impact on access to education, healthy foods, health care, and recreation facilities, and on physical safety, crime or victimisation, and other stressors (Williams et al., Citation2010).

This paper describes the living conditions of mine workers working at eight mines in South Africa in 2014. Although it was assumed that changes in government policy led to improvements in living conditions, there was a lack of evidence to support this hypothesis. The aim of this research was to assess the living conditions of workers in the SAMI, to assess changes made between the early 2000s and 2014, and to identify remaining shortcomings, with a view to assist in the development of strategies and prioritised interventions to further improve the living conditions of mine workers in South Africa.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a cross-sectional mixed methods study, as both qualitative and quantitative data were gathered, and methodological triangulation was used to verify the results.

2.2. Study population and sample

At the time of the study there were approximately 1700 operating mines and quarries in South Africa, and the industry directly employed close to 500 000 people (Republic of South Africa, Citation2011). The study population comprised all workers employed at eight mines in South Africa; the study mines were identified by commodity, and included those in the platinum (n = 3), gold (n = 2), coal (n = 1), diamond (n = 1), and manganese (n = 1) sectors. The participating mines employed approximately 10% of the SAMI workforce in 2014. The diamond mine was open-pit, while the seven other mines ran underground operations. The mines were located in six of the nine provinces in South Africa, and were purposively selected based on input from professionals with knowledge and understanding of the SAMI. A range of mining sectors was chosen so that this study could best represent the SAMI as a whole. The platinum and gold sectors employ the highest number of people in this industry, so more than one of each of these mines was selected.

The study participants included those in mine management, labour representatives, and mine workers. Those in mine management and the labour representatives were purposively selected based on the roles they played at the mines. Those in mine management included mine managers (general or operational), human resources managers, industrial relations officers, occupational health or wellness managers, safety managers, hostel managers and/or transformation managers, or those in equivalent or representative positions at each mine. Convenience sampling was used to recruit the mine workers that participated in the study, and included unskilled, semi-skilled, and skilled labourers performing work relating to production at the mines. Stakeholder interviews were conducted with 67 individuals in mine management and 18 labour representatives. Focus groups were conducted with 120 mine workers, and questionnaires were completed by 875 mine workers.

2.3. Study tools

The data collection tools developed for this study included a stakeholder interview and focus group question guide, and a questionnaire for mine workers. The interview and focus group guides consisted of open-ended questions to gain insight from the participants regarding their concerns relating to the living conditions of the mine workers at the mines and the services and facilities available to them. The questionnaire consisted of forced-choice questions relating to aspects such as worker demographics, living conditions, access to services and facilities, and lifestyle.

2.4. Study procedures

Data collection took place from June to November 2014. The interviews and focus group responses were voice recorded. The interviews with management and labour were conducted in English. Most of the interviews were held in one-on-one sessions; however, some were held with more than one individual at a time. The focus groups were conducted by trained research assistants who were fluent in the local languages (the languages that were most readily understandable by the participating mine workers). The research assistants also assisted the mine workers to understand and complete the questionnaires, to eliminate any barriers of language and literacy levels.

2.5. Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed, and the focus group responses were translated and transcribed. Thematic content analysis was used to identify main themes that arose. Data from the questionnaires were captured electronically, and basic statistical analyses were performed. A comparison of the data from different sources was conducted.

2.6. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the CSIR Research Ethics Committee and the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (reference and clearance certificate numbers 85/2013 and M140222, respectively). Permission was also provided by the mines to conduct the study at these sites. Voluntary informed consent was gained from each of the research participants. All data gathered in this study remain confidential.

3. Results

3.1. Interviews and focus groups with management, labour representatives, and mine workers

A total of 53 interviews with management, 11 interviews with labour representatives, and 14 focus groups were conducted across the eight mines. Discussions about the living conditions of the mine workers were categorised into the topics of hostel accommodation, other mine accommodation, home ownership schemes, housing outside of the mine, and services and facilities.

3.1.1. Hostel accommodation

The Mining Charter required the mines to convert or upgrade their hostels into single accommodation or family units by 2014. As this was the year in which the study was conducted, the studied mines had either completed these developments or planned to complete them by the end of the year. Some of the studied mines did not have hostel accommodation at all, or only had this for contract workers, while contract workers at some of the other mines were not able to reside in mine accommodation. The study participants generally expressed that the conditions in the hostels had improved. For example, a participant commented that ‘Those in the residences are happier now that there is only one person per room. They get more privacy […] The conditions have improved tremendously’. However, one hostel resident said that, ‘Even where we are staying in the hostel, we don’t like it. […] You can imagine how many years I have stayed away from my family […] Hostels are meant for school kids, not men with families’. Some concerns specific to the mine studied included the food provided, if applicable, and that workers wanted be allowed to have visitors to stay overnight. A problem with the reconverted hostels was that they housed fewer people than the hostels did in the past, which resulted in a shortage of accommodation, and led to more mine workers living in informal settlements. Some expressed the desire for more family accommodation to be provided.

3.1.2. Mine accommodation

Traditional mining villages existed at a number of the participating mines, in which houses were available for mine employees and their families to live in at a very low cost. Conditions here were generally seen to be good. However, this accommodation was generally limited to higher category workers, such as supervisors and managers. Examples of participant responses were:

When I started here I was given two options: either you get an LOA or you are given a mine house. The house where I am living is very safe and I cannot complain about anything. I enjoy staying there

and ‘We don’t all qualify for mine houses. Only those on a higher band get mine houses’.

3.1.3. Home ownership schemes

The management at many of the mines indicated that the mines were either in the process of planning or had already established facilitated home ownership schemes, through which mine workers could buy houses from the mines at subsidised rates. These schemes were particularly seen to assist those whose salaries were too low to qualify for mortgage bonds, but were too high to qualify for RDP or governmental housing. The need was highlighted by comments such as:

The money we get here is too little to afford houses. You find that you are the only one working in your family and you have to support a lot of people with it. How can I build a house with that little money I get? It’s difficult

and ‘We wish for the mine to provide us with houses. Not for us to rent, but the ones that we can be able to own’. It was generally agreed that the home ownership schemes were important mechanisms to improve the living conditions of mine workers. However, challenges that participants noted regarding the home ownership schemes included affordability and the distance of the housing from the mines. A participant stated: ‘It’s a good thing but the lower band employees cannot afford the houses’. Reasons for the far distances included spatial development planning and considerations of the lifespan of the mine, or because the areas close to the mines were tribal lands, so the mines were not able to build there. Some expressed that they wanted to own homes in rural areas. However, as this land belonged to tribal chiefs, it was not possible to obtain financing for these houses. Other workers already had homes in other areas and, as such, did not want to own a second house. A participant commented that: ‘Some of us are coming from different places, and some of us already have bond houses where we come from ’. However, another worker noted: ‘I’m originally from Lesotho. But even if home is Lesotho I would still want to own a house here because I work here’. Other workers wanted the mines to provide them with land or with financing to build their own houses.

3.1.4. Accommodation outside of the mine

The majority of mine workers lived outside of accommodation provided by the mine. Most of the participating mines offered LOAs to these workers. A participant commented, ‘We have moved away from the hostel-type accommodation, and hence the housing allowance that we are giving to people’, and ‘Getting a housing allowance to me is good in terms of freedom’. The main challenge that was noted regarding the use of LOAs was that this allowance was often not used towards decent housing, but was rather used to supplement the mine workers’ incomes. One participant noted, ‘Each person gets an LOA or housing allowance […] but the risk to that is not everyone uses this to get a proper house or apartment to live in’, while another said: ‘Most of us here prefer to stay in the townships because we cannot afford houses in town, and we don’t have money to build beautiful houses, so some of us stay in shacks’. A further comment was:

Hostels are a problem, and the dismantling of hostels brought in another problem, where three or four men are staying in a house […] And for hostel people to save money, a lot of people are staying in outside rooms or other places. Contractor workers are worse off.

Many of the mine workers were migrant labourers who opted to live in cheap, informal housing, such as ‘shacks’ or backrooms, close to the mine, and sent the extra money received from their LOAs to their rural homes. A number of workers expressed that they preferred renting, rather than staying in mine accommodation, as it gave them more freedom of choice. Many mine workers lived in various other forms of housing, including shacks, backrooms, RDP housing, rental rooms or houses, and their own homes in towns or rural areas. Problems that were encountered by many living in informal settlements or townships, and some in rural communities, included a lack of sanitation, water, and electricity, and poor roads. One participant noted, ‘The problems are with those staying outside, in shacks, where there is no sanitation, water and street lights’, and another noted, ‘Sometimes the community grows very fast and you find that some things (services) become limited for the people’.

3.1.5. Services and facilities

The services and facilities that were discussed included transport, health care, schooling, shops, and recreation. The adequacy of the services and facilities available to workers varied from mine to mine and also depended on where the mine workers lived.

Some of the mines provided transport, or transport subsidies, to their workers. Other forms of transport included workers’ private vehicles, public transport, such as buses and minibus taxis, and walking. Some of the roads to the mines were in poor condition, especially when it rained, and accidents and fatalities occurred. The problem of crime was also noted for those who walked to or home from work. These aspects were highlighted in comments, including: ‘The workers do not have enough transport. Some of them suffer, who are staying in the location’, ‘There’s no tar road to the mine. The last time I had an accident. Some of my colleagues had accidents too, on the same road’, and ‘When people have to walk there are muggings happening’.

Health care was also frequently discussed. Mine clinics offered services such as occupational and primary health care. However, it was not always possible for employees’ family members or contract workers to be treated at these facilities. The health care available outside of the mines varied. There were usually clinics available in the areas where the mine workers lived, and mobile clinics also operated. However, health care was difficult to access in certain areas, and the quality of and length of time taken to receive treatment at state services could be problematic. Hospitals were generally available, but the distance from some of the mines was a concern.

Other services that were discussed included schooling, shops, and recreation facilities. In terms of education, adult basic education and training (ABET) was often offered by the mines. There were generally crèches, nursery, primary, and high schools available in the areas surrounding the mines. However, tertiary education facilities, such as colleges or universities, were scarce. Small shops or kiosks were generally available on mine property or surrounding the mine, but the workers often had to travel to nearby towns to access a wider range of services. Recreation facilities, such as sports fields, were often available at the mines, but those in the communities surrounding the mines were not always adequate. A lack of recreation facilities was associated with increased alcohol and substance abuse, and crime.

3.2. Questionnaires completed by mine workers

A total of 875 questionnaires were completed by mine workers across the eight mines. The average response rate to the questions was 95% (±4%). The questions related to demographics, housing, and living conditions.

3.2.1. Demographics

Basic demographic characteristics of the study participants are displayed in . Most were male (89%); the majority (44%) were aged 30–39; and 58% had completed secondary education (Grade 12) or above.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics (n = 875).

Over half of the participants (54%) were married. The majority of the participants (92%) were black Africans. A wide variety of home languages were spoken, of which the most common was Southern Sotho (25%), followed by Setswana (20%), isiXhosa (17%), and isiZulu (10%). Most of the sample (87%) was South African, while the rest came from neighbouring countries. Half (50%) of the participants came from the same province as the mine in which they were working.

According to commodity, 37% of the participants worked at platinum mines, 30% in gold, 13% in diamond, 10% in coal, and 10% in manganese. The majority (82%) of the participants were permanent employees at the mines, while 18% were contract workers. In terms of shifts worked, 42% worked shifts of 12 hours or longer, and 46% worked night shifts in their work schedules.

3.2.2. Housing

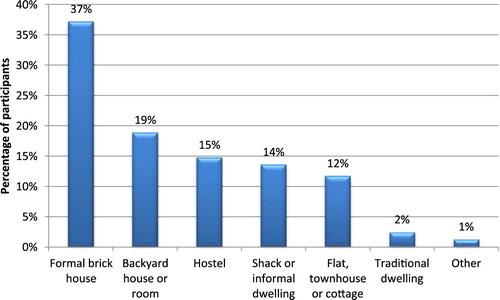

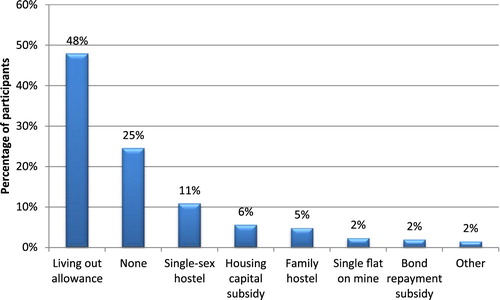

The types of dwellings in which the participants resided are illustrated in . Formal brick dwellings were the most common type (37%), followed by backyard rooms or houses (19%), hostels (15%), shacks or informal dwellings (14%), and flats, townhouses, or cottages (12%). Almost half (48%) reported to receive LOAs, a quarter did not have any housing arrangement with the mine, and 8% received housing capital or bond repayment subsidies (). Of those receiving LOAs, approximately 37% reported living in formal brick houses, 43% in shacks, informal dwellings, or backyard houses or rooms, and the remaining 20% in other accommodation, including flats, townhouses, cottages, and traditional dwellings.

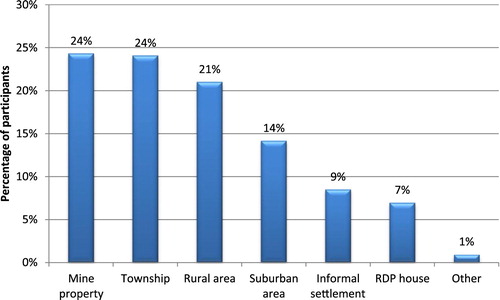

displays the areas in which the dwellings were located, of which the most common were mine property (24%), townships (24%), and rural areas (21%). In terms of housing tenure, 50% of the sample was renting, 32% owned their homes, 16% occupied their dwellings rent free, and 2% had ‘other’ arrangements. The participants were also asked whether they considered their dwellings by the mine to be their permanent homes. Around 41% said they did, while 59% said they did not.

Differences between the housing of contract workers and permanent employees were evident. Contract workers were more likely to reside in shacks, informal dwellings, or backrooms and less likely to stay in formal brick houses or hostels than the permanent employees. Contract workers were also less likely to have a housing arrangement with the mine.

The housing of participants working at mines of different commodities in the study sample also differed. The gold mines had a higher percentage of participants residing in hostels compared to the other commodities; the platinum mines had a higher percentage living in shacks or informal dwellings; and higher percentages stayed in formal brick houses for the coal, diamond, and manganese mines. However, longer travelling distances were also evident for those in coal, diamond, and manganese mines. LOAs dominated for all of the mines except for the diamond (open-pit) mine, where most participants reported having no housing arrangement with the mine.

3.2.3. Living conditions

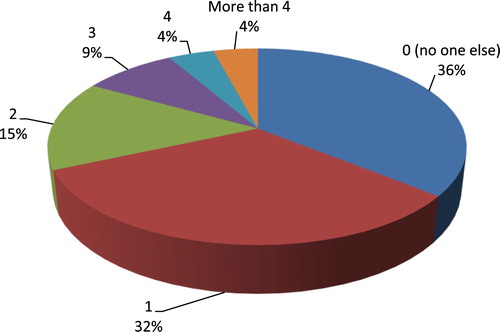

Participants were also asked about the level of crowding in their dwellings, their access to services and facilities, and disturbances they faced near to their dwellings. illustrates the number of people with whom the participants shared their rooms, wherein 36% had their own room, 32% shared a room with one other person, and 32% shared with two or more others. Of those reporting to live in hostel accommodation, 58% did not share a room with anyone else, 17% shared with one other person, 7% with two others, and 18% with three or more other people.

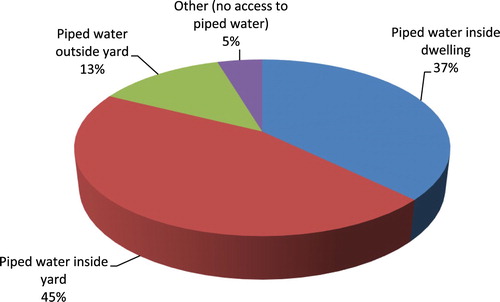

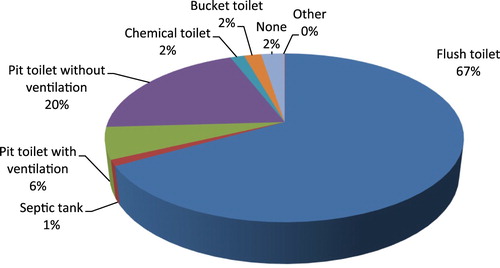

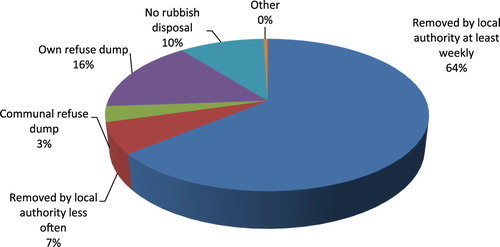

As can be seen in , around 82% of the sample reported access to piped water in their dwellings or in their gardens, while 13% had access to piped water outside of their gardens, and 5% did not have access to piped water. Electricity was the main source of energy that was used for lighting (92%), cooking (88%), and heating (71%), while other sources of fuel included gas, paraffin, and wood. The majority of the participants had flush toilets (67%), while 26% made use of pit toilets (with or without ventilation), and 6% used bucket toilets, chemical toilets, or did not have toilet facilities (see ). The majority of the sample (71%) had their refuse removed by a local authority, while 19% used their own or a communal refuse dump, and 10% had no mode of refuse disposal (see ). Those staying in shacks, informal dwellings, or backrooms reported lower access to services compared to those in formal dwellings and hostel accommodation. Similarly, contract workers had less access to services than permanent workers. Those from the platinum and manganese mines, which also employed higher percentages of contract labour and were more commonly located in rural areas, reported lower levels of access to services than workers from the other mines.

Participants were asked to rate how often they faced various disturbances in the areas of their dwellings, on a scale of ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘seldom’, and ‘never’. Noise and violence or crime, were the most commonly reported disturbances (62% and 57% of the participants indicated these were ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ experienced, respectively). The other disturbances listed were dust or smoke (48%), no drinking water (46%), bad smell (45%), littered environment (44%), and damage to buildings (32%).

In terms of access to health care, 82% of the participants indicated that they had access to what they considered to be proper health care at work, and 75% said they had access to proper health care close to their dwelling. Buses were the most commonly used mode of transport to get to and home from work (22%), followed by minibus taxis (21%). Private vehicles were also common, and 16% drove these, while 5% made use of lift clubs in these vehicles. Around 19% of the participants used company transport to get to and from work, while 14% walked and 3% used a combination of modes of transport.

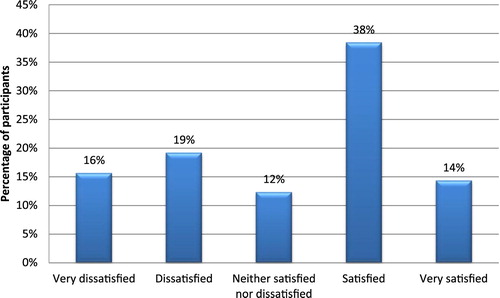

The participants were also asked to rate their levels of satisfaction with their living conditions and their quality of life. Around 35% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their living conditions, 12% were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, and 52% were satisfied or very satisfied (see ). In terms of quality of life, 30% considered theirs to be poor or very poor, 19% as neither poor nor good, and 51% as good or very good. Levels of satisfaction with living conditions and good quality of life reported by permanent employees were 54% and 51%, respectively, compared to 48% for both in contract workers. Satisfaction with living conditions and quality of life was highest for participants at the coal mine and lowest at the platinum mines.

3.3. Comparison of data from literature, interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires

The qualitative data gathered in the interviews and focus groups were compared with the quantitative data gathered in the questionnaires. The housing and living conditions of the participating mine workers were also compared with findings from studies in the SAMI in the past in order to assess general developments. While the study participants were not entirely representative of the SAMI, the data are believed to provide a general depiction of the living conditions of mine workers in South Africa.

Housing arrangements provided in the SAMI include hostel accommodation, facilitated home ownership schemes, and the use of LOAs. When comparing current data to that obtained from a study conducted by Lewis (Citation2003), it is evident that fewer mine workers resided in single-sex hostels in 2014 (11%) compared to the early 2000s (46%), while more workers received LOAs (48%) compared to the previous study (31%). This finding was expected, as a result of industry preferences and Mining Charter requirements for the upgrading and conversion of hostels. The hostel room occupancy rate was considerably lower compared to the past, as Lewis reported only 18% residing in rooms with four occupants or less, compared to 82% in the current study.

Compared to findings from a study relating to living conditions in the SAMI by Marais & Venter (Citation2006), mine workers appeared more satisfied with their living conditions in 2014. This is likely due to policy changes and initiatives that have been implemented by the industry to redress challenges relating to living conditions. However, 35% of the participants in the current study did indicate dissatisfaction with their living conditions. This could be a result of factors such: as not being able to live with families; affordability; a lack of access to services such as water, sanitation, and electricity; poor roads; transport challenges; noise; and crime.

Additionally, challenges with access to health care were indicated in the interviews and focus groups, including a lack of access for contract workers and for mine workers’ family members, and the accessibility of health care in the communities surrounding the mines. In the questionnaires, 82% of the participants reported that they had access to proper health care at work, while 75% reported to have access to proper health care close to their dwellings.

Comparisons between permanent and contract workers, and between participants from mines of different commodities, were also made. Contract workers were more likely to stay in informal dwellings, have less access to services, and report lower quality of life than the permanent employees. Those working at the platinum mines were most likely to stay in informal housing and reported lowest satisfaction with living conditions, compared to the other mines.

4. Discussion

Living conditions in the mining areas of South Africa are shaped by government and mine policies and regulations, as well as personal choices. This is evidenced by changes in living conditions in the SAMI that have occurred since the early 2000s.

Legislation aimed at reducing occupancy rates in hostels and the provision of LOAs has resulted in fewer mine workers residing in mine hostels and more workers residing in informal settlements surrounding the mines. The reduction of hostel occupancy rates is important to safeguard worker privacy and freedom, but has resulted in fewer being able to stay in hostel accommodation. Additionally, an unintended result is that many workers opt to live in sub-standard conditions in order to save money received from the LOA. As workers move away from hostels, reduced access to services and amenities, travelling distances, transport challenges, and crime are factors that can affect health, safety, and wellbeing.

A lack of decent and affordable housing, particularly family housing, for mine workers to rent or buy was a challenge in this study. A number of mine workers expressed the wish to own houses in mining areas. Home ownership schemes proposed by mines are a means to assist with this. However, the uptake of these appeared to be low; many of these plans were still in the development phase, and affordability and the location of the houses were problems noted by the study participants. Migrant workers were also less likely to want to own houses close to the mine. The migrant workforce in the SAMI is steadily decreasing, but still plays a significant role in the mining industry. It is evident that some workers who live away from their families while working at the mines and who opt to live outside of hostel accommodation may set up second families in mining areas, which can increase financial and social strains.

Important differences in living conditions between mines and between worker groups were also observed. A variation in living conditions between different mine types was evident, such as the higher percentage living in hostel accommodation in the gold mines, in informal dwellings in the platinum mines, and in formal dwellings further away from the mines in the coal, diamond, and manganese sectors. While differences were noted across commodities, some of these findings could also result from attributes of the specific mines sampled. Differences in the location of the mines in relation to urban centres, municipal or tribal authorities, and differences in socioeconomic status and income of the workers at mines of different commodities are also likely contributors. In terms of worker status, contract workers were more likely to live in informal settlements and have less access to services than permanent employees. Contract workers can experience greater challenges as a result of receiving fewer benefits, such as housing and transport, and generally lower pay than permanent employees.

Successful collaboration between relevant stakeholders, including companies, the government, and the local community, is important for implementation of development goals. The mining sector in South Africa is currently dealing with sustainability-related concerns, including financial pressures, retrenchments, and labour unrest, and mines increasingly need to balance the needs of the workers with production pressures. Workforce needs include housing and service delivery. Mines have a responsibility in terms of Social and Labour Plans to uplift mining communities; however, the involvement of municipalities is vital for successful community development. The government should also play a role in these interventions and in the development of a holistic strategy for mining towns (SACN, Citation2017). In addressing sustainability in mining, Littlewood (Citation2014) noted that multi-stakeholder partnership is vital and that planning and decision-making should be transparent and participatory.

Further research would assist in developing solutions to address challenges facing the SAMI. The future of mining needs to be considered, and the effects that these changes could make should be evaluated. Additionally, a comparison of living conditions between the local and global mining industry could help to provide direction to housing strategies in the SAMI. Meanwhile, continued monitoring and evaluation in the current context remains necessary. The broader study from which this paper was based examined effects of the living conditions on mine worker health and safety. Further publication of these findings is warranted.

5. Conclusion

While there have been improvements to the living conditions of mine workers in the SAMI, various challenges still remain, and some new ones have developed as a consequence of policy changes. Some of the changes made include the upgrading or conversion of hostels into single accommodation or family units, to provide more privacy and dignity to the mine workers. The preference for single-sex hostel accommodation has been abandoned, and more mine workers are making use of LOAs. Mine workers are seen to reside in various types of dwellings in addition to hostels, such as formal brick houses, flats or townhouses, backyard flats or houses and shacks, in towns, townships, informal settlements, or rural areas. Many mines have implemented facilitated home ownership schemes in order to assist mine workers to own their own homes, and this is seen as a way to improve the quality of life of mine workers in the SAMI. Problems relating to the living conditions of mine workers included not living with families, affordability, distance away from the mines, transport issues, noise, and violence or crime. A lack of services such as water, electricity, and sanitation was also an issue at many of the mines. Access to adequate health care was also sometimes a challenge, especially for contract workers and the family members of mine workers.

Industry initiatives have highlighted the importance of partnerships, such as with government, in improving the living conditions in the SAMI. It is anticipated that compliance with these initiatives and continued commitment to the improvement of the living conditions and education and awareness of mine workers will contribute to improved health, safety, productivity, and wellness, and reduced instability in the SAMI.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Mine Health and Safety Council [project number SIM 130901] and the Young Researchers’ Establishment Fund [project number YREF 2014 024] for funding this study. We would like to thank the mines and each of the participants that were involved with the study for their input. We would also like to acknowledge Sophi Letsoalo and Siphe Ngobese, from the CSIR, and Yazini April, from the Human Sciences Research Council, for their roles as research assistants. Appreciation is also expressed to Sizwe Phakathi and Schu Schutte for acting as co-supervisors of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jodi Pelders http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4671-1951

Gill Nelson http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7815-3718

References

- Alnsour, J & Meaton, J, 2014. Housing conditions in Palestinian refugee camps, Jordan. Cities (London, England) 36, 65–73.

- Bezuidenhout, A & Buhlungu, S, 2011. From compounded to fragmented labour: Mineworkers and the demise of compounds in South Africa. Antipode 43(2), 237–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00758.x

- Burridge, R & Ormandy, D, 2007. Health and safety at home: Private and public responsibility for unsatisfactory housing conditions. Journal of Law and Society 34(4), 544–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6478.2007.00404.x

- Cloete, J, Venter, A & Marais, L, 2009. ‘Breaking new ground’, social housing and mineworker housing: The missing link. Town and Regional Planning 54, 27–36.

- Cronjé, F & Chenga, S, 2009. Sustainable social development in the South African mining sector. Development Southern Africa 26(3), 413–27. doi: 10.1080/03768350903086788

- Galobardes, B, Shaw, M, Lawlor, DA, Lynch, JW & Smith, GD, 2006. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 60(1), 7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531

- Lewis, P, 2003. Housing and occupational health and safety in the South African mining industry. Final Report. Safety in Mines Research Advisory Council. SIM 02-09-01.

- Littlewood, D, 2014. ‘Cursed’ communities? Corporate social responsibility (CSR), company towns and the mining industry in Namibia. Journal of Business Ethics 120(1), 39–63. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1649-7

- Marais, L, Burger, P & van Rooyen, D, 2018. Mining and community in South Africa: From small town to iron town. London: Routledge.

- Marais, L & Nel, E, 2016. The dangers of growing on gold: lessons for mine downscaling from the free state goldfields, South Africa. Local Economy 31(1-2), 282–98. doi: 10.1177/0269094215621725

- Marais, L & Venter, A, 2006. Compound, but … mineworker housing needs in post-apartheid South Africa. Africa Insight 36(1), 53–62.

- Republic of South Africa, 1996a. The constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Act No. 108 of 1996.

- Republic of South Africa, 1996b. The mine health and safety act. Act No. 29 of 1996. Department of Minerals & Energy.

- Republic of South Africa, 1997. Housing act. Act No. 107 of 1997. Government Gazette. No. 18521. Department of Human Settlements.

- Republic of South Africa, 2002a. Broad-based socio-economic empowerment charter for the South African mining industry. Act No. 53 of 2003. Department of Minerals & Energy.

- Republic of South Africa, 2002b. Mineral and petroleum resources development act. Act No. 28 of 2002. Department of Minerals & Energy.

- Republic of South Africa, 2008a. Mineral and petroleum resources development amendment act. Act No. 49 of 2008. Department of Minerals & Energy.

- Republic of South Africa, 2008b. Publication of the amendment of the broad-based socio-economic empowerment charter for the South African mining and minerals industry. Government Gazette, 20 September 2010, No. 33573. Department of Mineral Resources.

- Republic of South Africa, 2009a. Codes of good practice for the South African minerals industry. Government Gazette, No. 32167, Vol. 526. Department of Trade and Industry.

- Republic of South Africa, 2009b. Publication of the housing and living conditions standard for the minerals industry. Government Gazette, 29 April 2009, No. 32166. Department of Minerals & Energy.

- Republic of South Africa, 2009c. Simplified guide to the national housing code. Volume 1. Department of Human Settlements.

- Republic of South Africa, 2010. Revised social and labour plan guidelines. Pretoria: Department of Mineral Resources. http://www.dmr.gov.za/guidelines-revised-social-and-labour-plans/summary/119-how-to/221-guidelines-revised-social-and-labour-plans-.html.

- Republic of South Africa, 2011. Labour percentages per commodity. Department of Mineral Resources. http://www.dmr.gov.za/labour-statistics/viewdownload/145/570.html.

- Republic of South Africa, 2013. Framework agreement for a sustainable mining industry entered into by organised labour, organised business and government.

- SACN, 2017. Spatial transformation: Are intermediate cities different? Johannesburg: South African Cities Network.

- Statistics South Africa, 2011. Census 2011 statistical release (revised). P0301.4. Pretoria, South Africa.

- Williams, DR, Mohammed, SA, Leavell, J & Collins, C, 2010. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186(1), 69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x