ABSTRACT

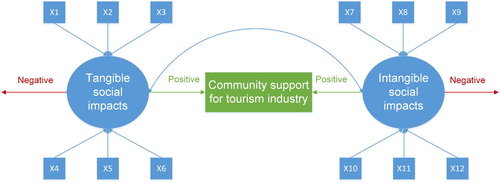

Residents living in communities with tourism activities form a vital part of the tourism industry; without their support, the industry will likely fail. It is the understanding of the Social Exchange Theory that residents should receive a form of physical award for accepting visitors into their environment, however, with the case of South Africa, there are various factors that inhibit the flow of such benefits. Regardless, the residents remain supportive. It was therefore determined that the intangible social impacts of tourism also play a vital role in fostering community support. To better manage both the tangible and intangible social impact perceptions, a framework was successfully developed by means of structural equation modelling (SEM). This novel framework may aid tourism managers to predict and strategically manage the social impact perceptions of tourism in a developing country such as South Africa in order to foster the vital community support for this industry.

Abbreviations: SEM: Structural equation modelling

1. Introduction

To date, the greatest number of social impact studies have focussed on the tangible aspects of tourism, such as economic contribution, job creation, and infrastructure development, as described for instance by Gursoy et al. (Citation2010), Hritz & Ross (Citation2010), Jurowski & Gursoy (Citation2004), Kibicho (Citation2008), Lapeyre (Citation2010), Muganda et al. (Citation2010), as well as Saarinen (Citation2010). However, South Africa (and perhaps other developing countries) exhibits a uniquely challenging situation where these tangible social impacts do not necessarily sift down to community level (Kuvan & Akan, Citation2005). This can be ascribed to the fact that South Africa is a developing country with prevailing socio-political, economic, and cultural limits (Tosun, Citation2000), together with a 25.5% (14 million people) unemployment rate in 2015 (STATSSA, Citation2016).

The fact that residents do not perceive a significant degree of tangible benefits from the tourism industry raises concerns, especially when taking into account that residents’ goodwill and support for the tourism industry is of utmost importance for the sustainability of the latter (Williams & Lawson, Citation2001; Gursoy et al., Citation2002; Jurowski & Gursoy, Citation2004; Kuvan & Akan, Citation2005; Park et al., Citation2012). To be more sustainable, one should strive toward maximising the positive impacts of tourism and minimising the negative (Kreag, Citation2007). Considering that residents do not receive significant tangible benefits from tourism, one might expect their support and goodwill to be withheld. The latter is not the case in South Africa (Kruger et al., Citation2010; Slabbert et al., Citation2012; Saayman et al., Citation2013; TREES, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). A study by Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016) revealed how intangible social impacts play a significant role in fostering residents’ support for the tourism industry (Scholtz & Slabbert, Citation2016). However, measuring residents’ tangible and intangible social impact perceptions proved difficult, therefore the need for a new social impact framework was discovered which would assist tourism managers and developers to properly manage and predict the social impact perception outcomes of tourism activities within a community.

2. Literature review

Various models and frameworks have been developed over the years to measure and better understand the social impacts of tourism. Smith's model of cross-cultural contact (Pearce, Citation1994) argued that the social impact of tourism is directly linked to the types of tourist who visit a destination (Woodside et al., Citation2009). The larger the groups, the greater their social impact. This model shares similarities with Doxey's Irridex model which, on the other hand, states that residents of an area that is strongly tourism-driven, portray different mental attitude phases towards tourists that vary between ‘euphoria’ and ‘antagonism’ according to their perception of the social impacts of tourism (Godfrey & Clarke, Citation2000). The limitations of this model include the following aspects: not all communities are homogeneous as people hold different political, religious, and social views; the model does not take the types of tourist and differences in culture into consideration; residents’ level of participation in tourism is not measured (Holden, Citation2006). Butler's tourist-area life cycle theory also reveals that as the growth and demand for tourism increase in an area, the more significant the impacts can be in the community, and the more negative (Butler, Citation1980). Another framework, known as the Social Representation Theory, measures communities as a collection of thoughts regarding certain aspects to obtain a representative opinion; however, community members’ attitudes and perceptions can be quite diverse, depending upon their respective cultures (Wagner et al., Citation2007; Moscardo, Citation2008). This is especially true for South Africa, seeing as this country is noticeably diverse in terms of culture – it boasts 11 official languages and is commonly referred to as the ‘Rainbow Nation’ (SAHO, Citation2014). A study by Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2017) also revealed how South African communities differ. Therefore, this framework is not fully compatible with a South African community structure. Pérez & Nadal (Citation2005) went further in their line of reasoning and divided community members into what they termed Host Community Perception Clusters, but this concept still does not fully capture the understanding of residents’ social impact perceptions. None of the mentioned models and frameworks can predict or provide adequate insights concerning the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism in a developing country such as South Africa.

2.1. The social exchange theory in understanding social impact perceptions

One of the fundamental, more simplified theories is the Social Exchange Theory (Gursoy et al., Citation2002; Jurowski & Gursoy, Citation2004; Wischniewski et al., Citation2009). This theory states that there should be a form of compensation when a particular individual or population is required to tolerate unwarranted activities (Devan, Citation2006). In this instance, the latter comprises the residents living in communities where there are well-established tourism industries. Such residents might have to live with negative impacts catalysed by tourism activities, including an excessive use of facilities causing traffic congestion or longer queues in shops (Godfrey & Clarke, Citation2000), or even unwanted activities such as crime and prostitution (Kim & Petrick, Citation2005). Through the social exchange theory, Andereck et al. (Citation2005) revealed that residents who perceive positive economic contributions also perceived greater tourism benefits and were more knowledgeable about the greater tourism impacts. Many other authors also made use of the social exchange theory to explain how residents react to the social impact of tourism (Ap, Citation1992; Gursoy et al., Citation2002; Ko & Stewart, Citation2002; Woosnam et al., Citation2009). However, the social exchange theory is concerned with the exchange of material or symbolic resources between people or groups (Sharpley, Citation2014). A study by Slikker & Koens (Citation2015) revealed how residents of the slums in Dharavi (in Mumbai, India) became less excited about the heavy presence of tourists over time as they did not experience significant benefits from tourism, yet they did not become negative with the tourists. Therefore, the social exchange theory did not apply here. Researchers such as Andereck et al. (Citation2005), Rasoolimanesh et al. (Citation2015), and Sharpley (Citation2014) argue the shortcomings of the social exchange theory, stating that other aspects such as place identity and attitudes, for instance, will also impact resident perceptions.

When taking into account that residents, to a great extent, only receive marginal quantities of tangible benefits from tourism, but continue to support this industry, it is highly possible that they receive benefits that might be intangible in nature (Richards & Palmer, Citation2010). This theory, as well as the other mentioned theories and frameworks, however, do not distinguish between the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism. As suggested earlier, in the unique South African situation, it would be prudent to make such a distinction when measuring the social impacts of tourism. This distinction was successfully made in a published study by Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016) where the word ‘tangible’ was defined as ‘something that one can possess as physical property, such as a higher income’ while ‘intangible’ refers to something which does not have a physical presence. Wren (Citation2003:44) furthermore states that intangibles are things that are more difficult to ‘see, perceive, or measure’, but that still carry value. The author names goodwill as an example of an intangible impact. It is something that can be experienced, but not easily measured or simply purchased for a fixed sum of money. Intangible benefits might also include social impacts such as community pride or protection of local cultures as compensation, for instance (Ntloko & Swart, Citation2008). This indicates that there might be more to intangible social impacts than previously thought and that such impacts could play a more significant role in fostering community support for tourism in a developing country, such as South Africa, than previously assumed.

This was found to be true in the studies by Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016, Citation2017) on which this current paper's framework will be constructed. These studies focus on the social impact perceptions of three South African communities with significantly tourism orientated economies, as well as comparisons between these communities. The communities included: Clarens (Free State Province), Jeffreys Bay (Eastern Cape Province), and Soweto (Gauteng Province) – these will be discussed in more detail in the method section.

2.2. Research context and hypotheses

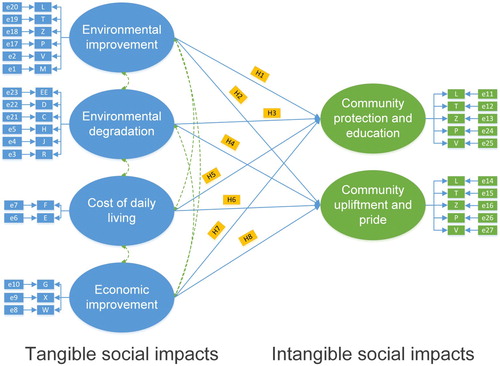

From the study by Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016), four tangible and two intangible social impact latent variables were discovered and published. The tangible latent variables included Environmental improvement, Environmental degradation, Cost of daily living, and Economic improvement; while Community protection and education, and Community upliftment and pride were found as intangible social impact latent variables (these factors will be discussed in more detail in the method section). The results of these factor analyses were compared to previous studies in Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016), where the largest finding was that the factor Economic improvement was rated significantly lower than in many other studies on social impact such as those done by Godfrey & Clarke (Citation2000), and Simpson (Citation2008), for example. The factor Cost of daily living was supported by previous studies that also showed that the cost of living is continually increasing (Godfrey & Clarke, Citation2000; Frauman & Banks, Citation2011). This was strange because based on the social exchange theory, the residents should have become more negative towards the tourism industry instead of displaying their goodwill as they continued to do (Saayman, Citation2000; Saveriades, Citation2000). The most significant finding from that study was that the intangible social impact factor Community upliftment and pride, obtained the highest mean value, meaning that the social exchange theory does not explain the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism efficiently and that the intangible social impacts of tourism might play a more significant role in residents’ perceptions than previously thought. Scholtz & Slabbert’s (Citation2016) paper can be summarised as displayed in (The factor analyses will be displayed in the Method section).

Figure 1. Authors’ compilation based on the findings of Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016).

This study, however, did not yet assist in the measuring and prediction of the social impact perceptions of residents. It also does not take into account how the various latent variables might influence one another, which would allow for better strategic management of social impact perception outcomes.

Therefore, a further study was done on the same data to confirm that factor and examine the differences between the three communities. Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2017) revealed that the communities’ data could successfully be pooled together and factorised and that there were clear differences between these communities. The communities differed in terms of some socio-demographic aspects such as average age (Clarens & Jeffreys Bay = 12 years; Soweto = 19 years), influence of tourism on their personal lives (Clarens experienced more positive impacts, Jeffreys Bay and Soweto less positive), as well as involvement in the tourism industry (37% in Clarens, 17% in Jeffreys Bay and 10% in Soweto). These differences, however, were not found as influential in residents’ perceptions of the tangible and intangible social impacts, yet it was discovered that residents from these three communities do differ regarding their tangible and intangible social impact perceptions in general. It was also found that the various tangible and intangible impact perceptions influence each other significantly. This study, therefore, revealed that tourism managers and promoters cannot approach all communities equally when measuring the tangible and intangible social impact of tourism, as each community views these tangible and intangible social impact latent variables differently, and their perceptions of these impacts also influence their perceptions of the other impacts significantly.

It was, consequently, deemed important to create a framework which could be applied to various communities in a developing country such as South Africa which would assist in the understanding and predicting of residents’ social impact perceptions over a broader spectrum of communities. Without other literature to indicate direction, except for the findings of Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2017), it was decided to set up the hypotheses as listed in to be incorporated into a novel social impact measurement framework which will take tangible and intangible social impact perceptions into account, and which could also be used in various strongly tourism-orientated communities in a developing country such as South Africa.

Table 1. Hypothesis for the framework.

3. Method

This section will, firstly, provide background to the initial studies and then, secondly, continue with the development of the tangible and intangible social impacts framework.

3.1. Initial method and results

This research forms part of a process that commenced with an article titled ‘The relevance of the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism on selected South African communities’ (Scholtz & Slabbert, Citation2016). An exploratory research design was used in the latter because research on this approach to the topic was, to the researchers’ knowledge, non-existent.

3.1.1. Questionnaire development

In the study, a quantitative approach was used in the form of a non-standardised questionnaire which was devised from various other studies (Ntloko & Swart, Citation2008; Gursoy et al., Citation2010; Oberholzer et al., Citation2010; Monterrubio et al., Citation2011; Viviers & Slabbert, Citation2012). The questionnaire consisted of two main sections: Section A measured socio-demographic information, such as age, length of stay in community, and level of education; while Section B focused on thirty-one specific social impact statements (17 tangible, 12 intangibles), listed on a 5-point Likert scale (where ‘1’ = strongly disagree and ‘5’ = strongly agree). A Likert scale was used as it can measure to what extent the respondents agree with the social impact perception statements. The Likert scale statements were simplified as far as possible to ensure understanding amongst the maximum number of respondents who were from different cultural and language backgrounds. Face validity was obtained by requesting other experts in the field of sociology and tourism to review the questionnaire.

3.1.2. Sampling

The questionnaires were distributed using convenience sampling (non-probability) after the communities were stratified. The strata were selected based on their proximity to tourist-dense areas – it is the understanding that the residents living in these strata will feel the social impacts of tourism the strongest. For instance, those who live close to popular beaches, restaurants, and other forms of attractions, were included. Convenience sampling was selected as sampling method within the strata as an updated list of residents living in the sample area could not be obtained, and it is very difficult to approach people only at their homes seeing as their movements are very dynamic. Therefore any available, willing residents in the selected strata were sampled. Distribution took place in three South African communities with established tourism industries, derived from the specific attributes of each community. Fieldworkers approached people in malls, shops, on the streets and at their homes, where a screening question was used to determine if they were residents. The fieldworkers included various university students who could at least communicate in Afrikaans, English or an African language which is predominant in the regions where the surveys took place. The researchers trained the fieldworkers on how to approach respondents, distribute the questionnaires, as well as the extent to which they could assist respondents in completing the questionnaires. Fieldworkers assisted residents who struggle with understanding English, or any other statements made in the questionnaire in general.

The communities sampled included Clarens, Soweto, and Jeffreys Bay in South Africa. In Clarens (population of 751Footnote1), 251(n) questionnaires were collected between 24 and 26 August 2012. Clarens is a popular tourist destination due to its picturesque surroundings, interesting shops, art galleries, and street cafes (Clarens, Citation2015). Many homes in this community are holiday homes, meaning that many potential respondents could not be reached during the survey. Soweto (population of 1 271 6281) was chosen for its historical and cultural appeal – the citizens here played a role in the abolishment of apartheid. Other attractions such as Nelson Mandela's home and traditional pubs (known locally as shebeens or taverns) are found here (SA-Venues, Citation2016). A total of 375(n) questionnaires were collected here between 13 and 16 September 2012. The third community, Jeffreys Bay (population of 27 1071, 417 questionnaires obtained) is a coastal town, world-renowned for its surfing opportunities. This town is also bordered by nature reserves and rivers (Jeffreys Bay Information, Citation2014). This survey took place from 7 to 13 October 2012. The data from the three communities was pooled to form a total sample of 1043 questionnaires. Krejcie & Morgan (Citation1970) recommend that one should obtain a sample size of at least (S) 384 for a population (N) of 1 000 000 to have a representative sample. For this reason, we deemed the pooled sample as adequate.

The questionnaires were captured in Microsoft Excel© for initial analysis, while the statistical program, Statistical Package for Social Sciences or SPSS (2012 edition) was used for further statistical analysis. These analyses consisted of two stages: the first was intended to compile the socio-demographic profile of the residents using descriptive statistics, while the second was designed to determine if the social impacts statements could be clustered into tangible and intangible social impacts using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses.

3.2. Exploratory phase

In the first paper by Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016), two principal component exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) were used to categorise the social impact statements into tangible and intangible social impacts. The EFAs made use of Oblimin Rotation with Kaiser's normalisation (see ). Initially, four tangible and three intangible social impact factors were extracted. The former social impacts accounted for 55.6% of the total variance while the latter ones accounted for 50.37% of the explained variance. The Kaizer-Meyer-Olkin measure of sample adequacy was 0.84, indicating that patterns of correlation were compact and, therefore, yielded distinct and relative factors (Field, Citation2005).

Table 2. Tangible and intangible social impacts factor analyses.

The tangible social impact factors were: Environmental improvement (), Environmental degradation (

), Cost of daily living (

), and Economic improvement (

), while the intangible factors were: Community upliftment and pride

and Community protection and education (

. Due to a low reliability coefficient (0.40), the third intangible social impact factor, Community disruptions, was omitted (Lee, Citation2011).

3.3. Confirmatory phase

The second phase of the study was published by Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2017), in a paper titled ‘Tourism is not just about the Money: A comparison of Three South African Communities’. The method and results of this study will be discussed here.

To determine whether the data from the communities could be successfully pooled, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. According to , the model-data-fit for the three communities fit. The CMIN/DF (minimum value of discrepancy divided by value of freedom) obtained a value of 4.555 (which is between the suggested values of 2 and 5), while the relative fit measure, CFI (component fit index), recorded a value of 0.860 (the closer to 1, the better). The RMSEA (root mean square of approximation), which is the fit measure based on non-central chi-square distribution, obtained a value of 0.058 (a value below 0.08 is good). The RMSEA's lower and higher limits of a 90% confidence interval were 0.055 and 0.062, respectively (Hooper et al., Citation2008; Arbuckle, Citation2012). The results were published in Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2017) where it was found that the data could successfully be pooled. To determine how these latent variables influence one another, the researchers made use of structural equation modelling (SEM).

Table 3. Model-data-fit.

3.4. The relationship between the tangible and intangible social impacts

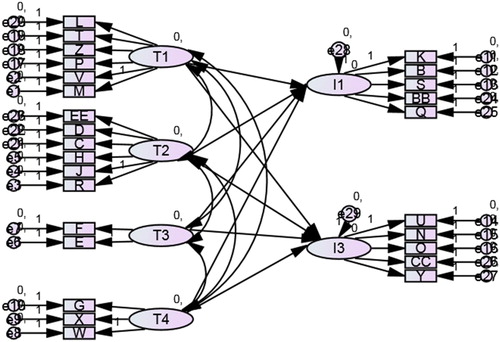

In this section, the researchers made use of SEM to determine the causal relations among measures as well as latent variables between the tangible and intangible social impacts of the sample communities (Mueller & Hancock, Citation2010). SEM was used as it assists researchers to study real-life phenomena (Nunkoo et al., Citation2013) by ‘testing measurement, functional, as well as predictive hypotheses that approximate world realities’ (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012). According to Karimimalayer & Anuar (Citation2012), it is a powerful multivariate technique that assists researchers in measuring the direct and indirect effects, as well as performing test models with multiple dependent variables. Instead of using various single regression analyses to measure the effects between various variables, a SEM makes use of numerous regression calculations concurrently. Although it is mostly used as a confirmatory technique, it may also be used in exploratory research. Many other studies, including Nunkoo & Ramkissoon (Citation2012), Nunkoo et al. (Citation2012), as well as Vargas-Sanchez et al., (Citation2011), for instance, also successfully used SEM to test their theoretical models or frameworks. The researchers commenced by using the tangible and intangible social impact latent variables to create a theoretical framework (see ). The analyses undertaken to develop the said framework, as well as the final framework, were carried out with the computer software known as AMOS v 21.0.0.

The theoretical model indicates the following latent variables as tangible social impacts: T1 symbolises environmental improvement, T2 environmental degradation, T3 the cost of daily living, while T4 symbolises economic improvement. On the other hand, I1 (community protection and education) and I3 (community upliftment and pride) all represented the latent variables for intangible social impact. No previous studies could be found, except for Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016, Citation2017), that measured the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism; therefore, it was decided to explore the influence of all latent variables on each other in order to explore all possible latent variable interactions, as shown with the hypotheses developed in in the literature section.

4. Results

This section will report on the relationships between the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism on the three sample communities, as well as discuss whether the hypotheses in are supported or rejected. The hypotheses listed in are illustrated in .

Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was selected to estimate the models because it has been indicated by Olsson et al. (Citation2000) as the most robust technique. displays the ML estimates, where it was found that only two of the eight paths were not statistically significant, thereby occasioning their rejection.

Table 4. Maximum likelihood (ML) estimates – regression weights of structural part of the model.

From , it was found that the following hypotheses were supported:

H1 falls within the 5% significance level with a standardised path coefficient of .946 (p < 0.001), thereby confirming the hypothesis which states that there is a direct relationship between environmental improvement and community protection and education.

H2, also within the 5% significance level with the standardised path coefficient of .963 (p < 0.001), confirms the hypothesis which states that perceived environmental improvement will positively influence community upliftment and pride.

H3 yielded a fairly low standardised path coefficient of .239 (p < 0.001). Stated, differently, residents who believe that tourism contributes to environmental degradation will more likely feel that tourism will positively influence community protection and education, but to a less significant extent.Footnote2

H5 was supported at p-value = 0.035 and a negative standardised path coefficient value of −.105 (p < 0.001). Residents who experience an increase in the cost of living, furthermore perceive a slight decline in the contribution which tourism makes to community protection and education.

H6, with a significant p-value of .007, and a low positive standard path coefficient .139 (p < 0.007), indicates that an increase in the daily cost of living as a result of tourism will influence a slight increase in community upliftment and pride.

H8 was confirmed at the 5% significance level, with a negative, low standardised path coefficient at −.204 (p = 0.004). In other words, residents perceive a slight decrease in community upliftment and pride in areas where higher levels of economic improvement are experienced.

5. Discussion

Although this study, in its totality, revealed a plethora of findings, only the findings applicable to the development of the social impact framework are discussed.

The overall finding is that the proposed framework does contribute towards the prediction of local communities’ social impact perceptions from both a tangible and intangible social impact point of view. This is especially important in a developing country such as South Africa where other, dated frameworks and models cannot comprehensively assist one to understand the social impacts of tourism in a country experiencing so many challenges and such a wide variety of cultures and beliefs. When the authors examined the specific hypotheses formulated for this study, the majority of hypotheses were supported.

Firstly, the tangible social impact factor, environmental improvement, was found to positively impact the two intangible social impact factors: community protection and education as well as community upliftment and pride. Similar findings were made by Besculides et al. (Citation2002) where community members felt that protecting the environment where the residents live, helps protect their culture regarding cultural and religious sites, as well as their distinct cultural atmosphere. Researchers such as Cooper & Hall (Citation2008) and Andereck et al. (Citation2005) found that improved surroundings and the development of recreational facilities to entertain visitors can also provide recreation and relaxation to the residents and influence positive, educational interactions with visitors. Further, it raised awareness amongst younger members of the community to also appreciate their cultural lifestyle. Therefore, improving the environment using, for instance, a greening initiative, as well as building tourism facilities and developing infrastructure in line with ecotourism guidelines, should form an integral part of tourism planning processes. From taking care of the environment in which residents live, it follows that community protection and education, as well as community upliftment and pride, will be enhanced. In totality, tourism development should lean more towards community-based tourism.

Secondly, it was also found that the tangible social impact factor, the cost of daily living, also influenced both of the intangible social impact factors mentioned, but in different manners. An increase in the cost of daily living fosters community upliftment and pride, which means that residents might feel proud that their community is worth more (in an economic sense). This is explained in a publication by Eldred (Citation2012) where the author states that civic pride and community spirit increases the value of a neighbourhood. Also, increased value of a neighbourhood (higher prices) can also positively influence community pride. In contrast, an increase in the cost of daily living exercises a negative influence on residents’ perceptions of community protection and education. Studies by Godfrey & Clarke (Citation2000), Goeldner & Ritchie (Citation2003) and Frauman & Banks (Citation2011) corroborate the latter situation by revealing how the cost of living is rising and how it inhibits residents’ chances of taking part in tourism activities, and possible degrade their lifestyles seeing as they have to cut back on spending on items they might have been used to purchasing. During tourism planning and development in such communities, measures should be taken to ensure that residents can afford everyday living by helping them achieve a higher income. This could be achieved by mostly employing mainly residents in the tourism industry and by inculcating skills where there are none, rather than outsourcing to skilled workers. This will also minimise economic leakage from the community. Tourism marketers should furthermore market the destination as a value for money, premium holiday destination, which in turn will foster a sense of community pride. The importance of incorporating community members into the tourism industry has been revealed by authors such as Jurowski & Gursoy (Citation2004), Kuvan & Akan (Citation2005) as well as almost any tourism textbook.

Thirdly, the intangible social impact factor, community protection and education, was positively influenced by the tangible social impact factor, environmental degradation. In essence, this means that residents will continue to experience community protection and education, regardless of environmental degradation. It should also be noted that the standardised path coefficient is low, and therefore that the direct effect between these two social impacts will be less significant. The descriptive statistics did, however, indicate that respondents felt that tourism does not contribute to environmental degradation and, therefore, indicated a positive response. Fourthly, residents observed a decrease in community upliftment and pride (intangible social impact factor) when economic improvement (a tangible social impact factor) was observed. A possible reason for this could be that only a small number of residents personally experienced economic improvement, rather than the community as a whole. This situation was also found in Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016), and Tosun (Citation2000), for instance. Tourism should, therefore, be managed in such a manner that a larger number of residents will be able to experience economic improvement. This, again, reinforces the importance of relying on the local human resources to provide the impetus for the local tourism industry to develop a more sustainable economic system. Consequently, the intangible social impact, community upliftment and pride, will increase.

Lastly, it was found that economic improvements as a result of the tourism industry did not influence residents’ perceptions of tourism's contribution towards community protection and education. It might be the case that residents did not necessarily view economic improvements as a contributing factor about community protection and education. It might also be the situation that those residents (who usually make up the majority of people) who did not perceive significant economic improvements, were not able to view tourism as a contributing factor to community protection and education. This is corroborated in a study by Andereck et al. (Citation2005) which found that that those who do perceive the tangible social impact, economic improvements, are not influenced to see the negative impacts in a better light, meaning that this tangible social impact does not influence residents’ support for the industry. This strengthens the argument made in Scholtz & Slabbert (Citation2016) which stated that tangible benefits might not always be the most important social impact.

When measuring social impact on a community, the findings of this research should be taken into account; the role of intangible impacts should be regarded as equally important to that of tangible impacts. From the latter, the role of the tangible and intangible social impacts becomes apparent, consequently endorsing this remodelled framework, especially for the South African situation.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the researchers devised a remodelled approach to measuring the social impacts of tourism to understand and predict these in a developing country such as South Africa. This was achieved by distinguishing between the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism. To the researchers’ knowledge, this was the first time that a study of its kind has been undertaken; therefore, various contributions were made to this field of knowledge.

Firstly, this study contributes towards an innovative approach towards the understanding, measuring, and analysing of the social impacts of tourism by distinguishing between the tangible and intangible social impacts. The significance of this is that it takes South Africa's unique situation into consideration. Secondly, it contributes towards the understanding of the social impacts of tourism in three diverse South African communities with well-established tourism industries. Thirdly, this research reveals the importance of the intangible social impacts of tourism, especially in a developing country. This fills a gap in the current literature, in so far as the majority of social impact studies have concentrated on the tangible social impacts of tourism. The fourth contribution is that this study revealed that the intangible social impacts of tourism might well, in some cases, play a more important role in fostering community support for the tourism industry, compared to the tangible ones, thereby pointing to the importance of also managing the intangible social impacts.

The final, and probably the most important contribution is the practical use of this framework. It should ultimately assist tourism managers, marketeers, and developers to better understand and predict the social impacts of tourism in a developing country such as South Africa with its diversity of cultures. It can also be applied to other communities that are similar to those which formed part of this study, to help manage the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism towards fostering community support. Proper management is likely to contribute ultimately to a more sustainable tourism industry, thereby ensuring the success of this industry for a country that strongly depends on it. The reason why it can be applied to other communities was because this research examined communities that are diverse in terms of their economies and cultural composition, yet the confirmatory factor analysis could group them together – regardless of their different views. It was found that their differences did not impact their perceptions significantly, but rather that their tangible and intangible social impact perceptions influenced other tangible and intangible social impact perceptions.

This study has found that in a developing country such as South Africa, goodwill is not necessarily solely bought with money, but can also be earned through the appreciation of other unseen benefits.

Acknowledgements

The researchers firstly thank the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa for funding this project, secondly the community members of Clarens, Jeffreys Bay, and Soweto, and lastly the fieldworkers who distributed the questionnaires.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 STATSSA (Citation2016)

2 Please note that the descriptive statistics indicated that respondents felt that tourism did not contribute to environmental degradation and, therefore, indicated a positive response.

References

- Andereck, KL, Valentine, KM, Knopf, RC & Vogt, CA, 2005. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research 32(4), 1056–76. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

- Ap, J, 1992. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research 19(4), 665–90. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(92)90060-3

- Arbuckle, JL, 2012. IBM® SPSS® Amos™ user’s guide. http://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/documentation/amos/21.0/en/Manuals/IBM_SPSS_Amos_Users_Guide.pdf Accessed 5 April 2016.

- Bagozzi, RP & Yi, Y, 2012. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40, 8–34. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

- Besculides, A, Lee, ME & McCormick, PJ, 2002. Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 29(2), 303–19. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00066-4

- Butler, RW, 1980. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 24, 5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

- Clarens, 2015. Clarens. http://www.clarens.co.za/ Accessed 9 April 2016.

- Cooper, S & Hall, M, 2008. Contemporary tourism: An international approach. Elsevier, London.

- Devan, J, 2006. Social exchange theory. http://www.istheory.yorku.ca/Socialexchangetheory.htm Accessed 12 January 2016.

- Eldred, GW, 2012. Investing in real estate. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

- Field, AP, 2005. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Frauman, E & Banks, S, 2011. Gateway community resident perceptions of tourism development: Incorporating importance-performance analysis into a limits of acceptable change framework. Tourism Management 32(1), 128–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.01.013

- Goeldner, CR & Ritchie, JRB, 2003. Tourism: Principles, practices, philosophies. 9th edn. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey.

- Godfrey, K & Clarke, J, 2000. The tourism development handbook: A practical approach to planning and marketing. Cassell, New York.

- Gursoy, D, Jurowski, C & Uysal, M, 2002. Resident attitudes: A structural modelling approach. Annals of Tourism Research 29(1), 79–105. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00028-7

- Gursoy, D, Chi, CG & Dyer, P, 2010. Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of the sunshine coast, Australia. Journal of Rural Studies 22(2), 117–28.

- Holden, A, 2006. Tourism studies and the social sciences. Routledge, New York.

- Hooper, D, Couglan, J & Mullen, MR, 2008. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6(1), 53–60.

- Hritz, N & Ross, C, 2010. The perceived impacts of sport tourism: An urban host community perspective. Journal of Sport Management 24(2), 119–38. doi: 10.1123/jsm.24.2.119

- Jeffreys Bay Information, 2014. Jeffreys bay information. http://www.jeffreysbay-information.co.za/ Accessed 9 April 2015.

- Jurowski, C & Gursoy, D, 2004. Distance effects on residents’ attitude towards tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 31(2), 296–312. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2003.12.005

- Karimimalayer, MAA & Anuar, MK, 2012. Structural equation modeling vs multiple regression: The first and second generation of multivariate techniques. Engineering Science and Technology: An International Journal 2(2), 326–9.

- Kibicho, W, 2008. Community-based tourism: A factor-cluster segmentation approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 16(2), 211–31. doi: 10.2167/jost623.0

- Kim, SS & Petrick, JF, 2005. Residents’ perceptions on impacts of the FIFA 2002 world cup: The case of Seoul as a host city. Tourism Management 26(1), 25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.013

- Ko, D & Stewart, WP, 2002. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management 23(5), 521–30. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00006-7

- Kreag, G, 2007. The impact of tourism. http://www.seagrant.umn.edu/downloads/t13.pdf Accessed 7 July 2015.

- Krejcie, RV & Morgan, DW, 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30(3), 607–10. doi: 10.1177/001316447003000308

- Kruger, M, Saayman, A, Saayman, M, Slabbert, E & Laurens, M, 2010. Profile, social and economic impact of innibos arts festival 2010. Institute for Tourism and Leisure Studies, Potchefstroom.

- Kuvan, Y & Akan, P, 2005. Residents’ attitudes toward general and forest-related impacts of tourism: The case of Belek, Antalya. Tourism Management 26(5), 691–706. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.02.019

- Lapeyre, R, 2010. Community-based tourism as a sustainable solution to maximise impacts locally? The Tsiseb conservancy case, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 757–72. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2010.522837

- Lee, I, 2011. Transformations in e-business technologies and commerce: Emerging impacts. Idea Group, Hershey, PA.

- Monterrubio, JC, Ramírez, O & Ortiz, JC, 2011. Host community attitudes towards sport tourism events: Social impacts of the 2011 Pan American games. E-review of Tourism Research 9(2), 33–46.

- Moscardo, G, 2008. Building community capacity for tourism development. CABI, Wallingford.

- Mueller, RO & Hancock, GR, 2010. Structural equation modelling. In Hancock, GR & Mueller, RO (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences. Routledge, New York, NY.

- Muganda, M, Sahli, M & Smith, KA, 2010. Tourism’s contribution to poverty alleviation: A community perspective from Tanzania. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 629–46. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2010.522826

- Ntloko, NJ & Swart, K, 2008. Sports tourism event impacts on the host community: A case study of red bull big wave Africa. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 30(2), 79–93. doi: 10.4314/sajrs.v30i2.25991

- Nunkoo, R & Ramkissoon, H, 2012. Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Annals of Tourism Research 39(2), 997–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.11.017

- Nunkoo, R, Ramkissoon, H & Gursoy, D, 2012. Public trust in tourism institutions. Annals of Tourism Research 39(3), 1538–64. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.04.004

- Nunkoo, R, Ramkissoon, H & Gursoy, D, 2013. Use of structural equation modeling in tourism research: Past, present, and future. Journal of Travel Research 52(6), 759–71. doi: 10.1177/0047287513478503

- Oberholzer, S, Saayman, M, Saayman, A & Slabbert, A, 2010. The socio-economic impact of Africa’s oldest marine park. Koedoe 52(1), 1–9. doi: 10.4102/koedoe.v52i1.879

- Olsson, UH, Foss, T, Troye, SV & Howell, RD, 2000. The performance of ML, GLS, and WLS estimation in structural equation modeling under conditions of misspecification and nonnormality. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 7(4), 557–95. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0704_3

- Park, DB, Lee, KW, Choi, HS & Yoon, Y, 2012. Factors influencing social capital in rural tourism communities in South Korea. Tourism Management 33(6), 1511–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.005

- Pearce, PL, 1994. Tourist-resident impacts: Examples, explanations, and emerging solutions. In Theobald, W (Ed.), Global tourism: The next decade. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

- Pérez, EA & Nadal, JR, 2005. Host community perceptions: A cluster analysis. Annals of Tourism Research 32(4), 925–41. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.11.004

- Rasoolimanesh, SM, Jaafar, M, Kock, N & Ramayah, T, 2015. A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tourism Management Perspectives 16, 335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2015.10.001

- Richards, G & Palmer, R, 2010. Eventful cities: Cultural management and urban revitalisation. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

- Saarinen, J, 2010. Local tourism awareness: Community views in Katututra and King Nehale Conservancy, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 713–724. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2010.522833

- Saayman, M, 2000. En route with tourism. 2nd edn. Leisure Consultants and Publications, Potchefstroom.

- Saayman, A, Saayman, M & Scholtz, M, 2013. The socio-economic impact of Namaqua National Park on surrounding communities. Tourism Research in Economic Environs & Society, Potchefstroom.

- SAHO (South African History Online). 2014. South Africa’s diverse culture artistic and linguistic heritage. http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/south-africas-diverse-culture-artistic-and-linguistic-heritage Accessed 18 July 2017.

- Saveriades, S, 2000. Establishing the social tourism carrying capacity for the tourist resorts of the east coast of the Republic of Cyprus. Tourism Management 21(2), 147–156.

- SA-Venues, 2016. Map of Soweto, Gauteng. http://www.sa-venues.com/maps/gauteng/soweto.php Accessed 15 November 2015.

- Scholtz, M, & Slabbert, E, 2016. The relevance of the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism on selected South African communities. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 14(2), 107–28. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2015.1031796

- Scholtz, M & Slabbert, E, 2017. Tourism is not just about the money: A comparison of three South African communities. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6(3), 1–21.

- Sharpley, R, 2014. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of research. Tourism Management 42, 37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

- Simpson, MC, 2008. Community benefit tourism initiatives – A conceptual oxymoron? Tourism Management 29(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.005

- Slabbert, E, Manners, B, Viviers, PA, Botha, K & Saayman, M, 2012. Bemarkingsprofiel en gemeenskapspersepsie rakende Aardklop Nasionale Kunstefees 2012. Tourism Research in Economic Environs & Society, Potchefstroom.

- Slikker, N & Koens, K, 2015. “Breaking the silence”: Local perceptions of slum tourism in Dharavi. Tourism Review International 19, 75–86. doi: 10.3727/154427215X14327569678876

- STATSSA, 2016. Statistics by place. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=964 / Accessed 13 May 2015.

- Tosun, C, 2000. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management 21(6), 613–33. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

- TREES, 2014a. An analysis of the diamonds & dorings festival 2014: Attendees, local business owners & community members. Tourism Research in Economic Environs & Society, Potchefstroom.

- TREES, 2014b. An analysis and economic impact of the 2015 Comrades Marathon: Participants, spectators as well as local residents & businesses. Tourism Research in Economic Environs & Society, Potchefstroom.

- Vargas-Sanchez, A, Porras-Bueno, N & Plaza-Mejia, MA, 2011. Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism: Is a universal model possible? Annals of Tourism Research 38(2), 460–80. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.10.004

- Viviers, PA & Slabbert, E, 2012. Towards an instrument measuring community perceptions of the impacts of festivals. Journal of Human Ecology 40(3), 197–212. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2012.11906538

- Wagner, W, Duveen, G, Farr, R, Jovchelovitch, S, Lorenzi-Cioldi, F, Marková, I & Rose, D, 2007. Theory and method of social representations. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2640 Accessed 9 April 2016.

- Williams, J, & Lawson, R, 2001. Community issues and resident opinions of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 28(2), 269–90. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00030-X

- Wischniewski, J, Windmann, S, Juckel, G & Brüne M, 2009. Rules of social exchange: Game theory, individual differences, and psychopathology. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 33(3), 305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.008

- Woodside, AG, Megehee, C & Ogle, A, 2009. Advances in culture, tourism and hospitality research. Emerald Group, Bingley.

- Woosnam, KM, Norman, WC & Ying, T, 2009. Exploring the theoretical framework of emotional solidarity between residents and tourists. Journal of Travel Research 48(2), 245–58. doi: 10.1177/0047287509332334

- Wren, A, 2003. The project management A-Z: A compendium of project management techniques and how to use them. Gouwer Publishing Limited, Aldershot.