ABSTRACT

Despite the development interventions that have been adopted to help the countries caught in a downward spiral of impoverishment, their problems still persist. This paper focuses on the role that traditional foreign aid and the more recent bottom–up approach of supporting social entrepreneurs are playing to tackle the situation of extreme poverty in Zimbabwe. Drawing upon a narrative inquiry, 35 stories were collected to bring fresh insights regarding the realities of such interventions as they are experienced by the local people. The evidence shows the main shortcomings of the current development models and suggests that the improvement of a declining economy such as Zimbabwe would need the interaction of various factors, so that some interventions will appear significant only when the conditions of primary importance exist in the environment. Additionally, the engagement of local people seems to be a key aspect to the success of some of the support measures.

1. Introduction

Jeffrey Sachs, in his book The end of poverty, argued on how those who live in developed countries should help those caught in a downward spiral of impoverishment, at least to gain a foothold on the bottom rung from which they can then proceed to climb on their own (Sachs, Citation2005). To do this, he defended the establishment of a Big Plan – United Nations Millennium Declaration – that included in-depth diagnosis on the causes of poverty, key investments for removing them and financial plans using aid systems (Sachs, Citation2005). The target year for reaching the objectives – the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – was 2015. Nevertheless, there is no common view concerning such achievement.

The opponents to the traditional aid-based development model have long criticised its lack of effectiveness, especially in many of the declining economies in African countries. One of the main arguments is that where the political environment is perceived as unfavourable – as often found in countries with declining economies – supporting economic and social progress with traditional aid has no positive effect and is even wasted at best (Easterly, Citation2006, Citation2009; Moyo, Citation2009). In other sources the notion that poor countries can grow and develop on their own is supported (Collier, Citation2007; Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2011). Thus, from this point of view, any aid given to encourage development should start from below, that is, helping directly particular agents by using a bottom–up approach.

One of the most famous advocates of the bottom–up approach is the American economist William Easterly. His leading argument is that the best way of helping poor countries is through supporting the action of ‘searchers’ (Easterly, Citation2006), whom he identified as a kind of entrepreneur in the social sector. From Africa, his counterpart Dambisa Moyo, a native of Zambia, is widely recognised for criticising the traditional aid policy, while defending the promotion of internal solutions with social entrepreneurs as relevant protagonists (Moyo, Citation2009). Certainly, social entrepreneurs are gaining recognition for opening new avenues to the way developing and underdeveloped countries can meet some of their social needs (Urban, Citation2008; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2012), to the extent that most of the countries with high levels of poverty are trying to stimulate their activities with diverse support measures (Seelos, et al., Citation2006; Seelos & Mair, Citation2009; Haugh & Talwar, Citation2016). Yet, there are still doubts about the type of support that may work out better in each country.

In this article, we seek to illuminate this issue in the context of Zimbabwe by investigating how people perceive and experience both the support to social entrepreneurs and foreign aid as alternatives to fighting poverty. Concretely, drawing upon a narrative inquiry (Andrews et al., Citation2008), 35 people’s stories were collected and analysed through a thematic approach. The remainder of the article is structured as follows. In the next section we summarise how the foreign aid debate has been framed so far. Then, we look at the particularities of social entrepreneurs in developing and underdeveloped countries as they have been identified in the literature. In the following section, we explain the research methodology and context. We then present the findings of the study and, finally, we discuss them highlighting some concluding remarks.

2. The role of foreign aid in tackling poverty and promoting economic growth

Foreign aid has proven to be a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. For more than 60 years, it has been the main way the international community has tried to stimulate economic growth and address the problem of poverty in Africa (Sachs, Citation2005). Yet, literature is highly ambiguous regarding its outcomes. Aid-related success has been clear in areas such as the eradication of diseases or famine after wars and natural disasters (Becerra et al., Citation2014). But then, some components of foreign aid have led to adverse results, harming the economies of countries that they were trying to help (Easterly & Pfutze, Citation2008; Moyo, Citation2009; Easterly & Williamson, Citation2011). In this respect, there has been a lengthy debate among scholars concerning the pros and cons of food aid, as it is one of the most significant components of foreign aid (e.g. Gupta et al., Citation2004; Giella, Citation2016).

Evidence on how well food aid is targeted at those with the greatest need is mixed. While there are studies that recognise successful experiences (e.g. OECD, Citation2005; WFP, Citation2011), cases of food aid’s ineffectiveness and misuse are also large (e.g. Jayne et al., Citation2002; Barrett, Citation2010; Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2011). Banerjee & Duflo (Citation2011), for instance, referring to misuse of food aid have noted cases in which donors’ ‘strategic’ interests – colonial past and political or commercial alliances – were more important to decisions on their contributions than the real need existent in less developed countries. On other occasions, misconduct appears to be associated with the governments of recipient countries. Particularly, scholars have stressed the clientelism that surrounds the delivery of food aid in the African context, with public officials targeting urban ‘middle class’ populations while food assistance is hardly accessible to poorer rural households (Easterly & Pfutze, Citation2008; Moyo, Citation2009; Easterly & Williamson, Citation2011).

The impact of food aid on government revenues and economic activity of recipients has also been noted in both positive and negative terms. For example, Gupta et al. (Citation2004) make the point on the favourable effects of food aid in providing critical budget support and alleviating spending pressures on it to offset the adverse consequences of food shortages. But if food aid does not respond to the requirements of the targeted populations, or it is intertwined with corruptive institutions, aid might produce traumatic consequences by creating a long-term dependency syndrome in which the whole food sector might be negatively affected (Ouattara, Citation2007). Changes in consumption patterns, collapse of national prices, diminishing local food production, disruption of local markets and disincentives to produce food have all been acknowledged as possible adverse results (Sinyolo et al., Citation2017).

More broadly, for any component of foreign aid, its impact on growth and poverty reduction has been recognised to be mediated by the political institutions and governance of recipient countries. In fact, insights regarding the extrinsic value of political institutions have reshaped the terms of aid effectiveness debate as both policymakers and researchers have become increasingly concerned with the negative effects of poor governance (Ilorah, Citation2008; Molenaers et al., Citation2015). To address the challenge, the point here has been the establishment of political conditionalities. The punitive rhetoric that accompanies this approach shows that aid providers could sanction cases of human rights violations and democratic decay. Yet, in many post-2000 political conditionalities, democratic governance has turned to be both an objective and a condition for aid (Fisher, Citation2015).

Aligned with conditionality, during the last years, there has been a significant sectoral shift in aid (Petterson, Citation2007). Aid is thus targeted at specific public expenditure sectors, which often include social infrastructure, health, education or agriculture (Mawdsley et al., Citation2018). Even though this modality has been more effective on average than previous forms of aid, problems also occur, for example, when recipient governments divert funds from one specific sector to others – the so-called ‘fungibility problem’ (Petterson, Citation2007). In such cases, donors may end up financing something completely different from what was initially intended.

Overlooking recipient countries’ social customs seems to be behind many failures on foreign sectoral aid. In Altaf’s (Citation2011) study, she provides evidence of how some social sector development programmes were designed with conceptual frameworks that reflected an inadequate knowledge of the cultural realities of recipient countries; consequently, they became inappropriate and failed to attain the expected results. Such outcomes echo the ideas of development of the Nobel Prize laureate Amartya Sen (Citation1999), who argued that development – and development aid – should be understood more widely than in physical terms; not just referring to an economic dimension but also a socio-cultural one. Lastly, a recent research stream, framed in what Mawdsley et al. (Citation2018) describe as ‘beyond aid agenda’, is bringing new insights that are invalidating the myth of foreign aid working from an exclusive economic perspective, in cultural isolation. While this form of aid is not exempt from criticism (Mawdsley et al., Citation2018), a peculiar feature is its enthusiastic welcome to new actors on both sides as contributors in development funding – mainly the private sectors – and on the side of the recipient countries as small producers or entrepreneurs. Therefore, this view partially supports the thesis of the bottom–up approach and the importance ascribed to social entrepreneurs (Easterly, Citation2006; Moyo, Citation2009). To this issue we turn now.

3. The role of social entrepreneurs in developing and underdeveloped countries

Despite the conceptual disagreements that remain among scholars, in a very broad sense the social entrepreneur is normally referred to as a particular type of agent who offers solutions to a range of social problems through innovative ways (Bornstein, Citation2007; Zahra et al., Citation2009; Huybrechts & Nicholls, Citation2012). The distinctiveness with respect to traditional entrepreneurs comes mainly from the fact that the initiatives pursue a social value to further the economic effects on the transactional parties (Austin et al., Citation2006). Thus, while behaving as entrepreneurs in terms of dynamism, personal involvement and innovative practices, social entrepreneurs’ peculiarity is found in their drive to generate social impact by tackling problems previously overlooked by business, governmental and non-governmental organisations. Precisely, due to their social drive, previous works have attributed the role of catalysts for social change and transformation to social entrepreneurs (e.g. Seelos & Mair, Citation2009; Zahra et al., Citation2009); and such role has reinforced their recognition in developing and underdeveloped countries (Haugh & Talwar, Citation2016).

The complexity and magnitude of the social problems in less developed countries (e.g. constraints in healthcare services, lack of basic service provision such as access to clean drinking water, electricity, local transport) permeate a certain distinctiveness in social entrepreneurs’ role and activities, when compared with their counterparts in developed areas (Urban, Citation2008; Kerlin, Citation2009; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2012; Littlewood & Holt, Citation2015). Referring to the context of South Africa, for example, Littlewood & Holt (Citation2015) have shown how the environment influences the social needs and the range of activities that may be organised under the form of social enterprise. In the same context, Karanda & Toledano (Citation2012) identified notable social enterprises in sectors such as security, basic health or education. It is important to note that such sectors have been traditionally targeted by foreign sectoral aid through some of its programmes but, alternatively, are often the ground for public services or private businesses in developed economies.

In countries with high levels of poverty, mention is also made of the participative role that social entrepreneurs play with poor and marginalised communities (Urban, Citation2008; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2012; Rivera-Santos et al., Citation2015). When talking about this role, Rivera-Santos et al. (Citation2015) highlight how social entrepreneurs from sub-Saharan Africa are rebuilding rural communities by engaging poor and disadvantaged groups in a more inclusive manner. Their capacities to discover and understand the needs of the poor are noticeable since most of them have been exposed to poverty situations. Similarly, Seelos et al. (Citation2006) had already emphasised social entrepreneurs’ transformative impact within poor communities in the context of helping them to escape from the poverty–conflict trap and contributing to achieving the MDGs. A remarkable argument in this respect is that social entrepreneurs are more advantageous, when compared to centralised policy planning, because they often enjoy greater freedom of action to decide quickly when needed (Seelos et al., Citation2006; Seelos & Mair, Citation2009).

The strong ethnic and religious identities that prevail among the inhabitants of Southern and sub-Saharan Africa are also noted to be influencers of the caring role that social entrepreneurs play within their communities (Karanda & Toledano, Citation2012; Rivera-Santos et al., Citation2015). In some countries, a Christian identity built on the example of Jesus’s compassion for the needy and outcasts influences social entrepreneurs’ orientation in tackling problems with a special sensitiveness. In other countries, the typically sub-Saharan African Ubuntu approach, grounded in an interdependent view of the world, has an impact on how social entrepreneurs emphasise the inclusion of communities (Rivera-Santos et al., Citation2015).

However, despite the significant role of social entrepreneurs in poor communities, its practice can also become extremely difficult. Indeed, the success of the new social enterprises remains constrained due to a number of macroeconomic and structural factors (Masendeke & Mugova, Citation2009; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2012; Littlewood & Holt, Citation2015). Deficient infrastructures and lack of skills among emerging young social entrepreneurs are critical issues (Ligthelm, Citation2008). But political uncertainty, conflicts, crime, immigration and economic incompetence are also problems that make the entrepreneurial process harder than in other parts of the world (Masendeke & Mugova, Citation2009; Littlewood & Holt, Citation2015). Thus, even though there may be a number of potential social entrepreneurs, the African context suffers from lack of an appropriate ecosystem for social entrepreneurship to grow (Stam, Citation2015). As a consequence, social entrepreneurs’ support measures have been justified. In Southern Africa, so far, two main tendencies stand out in support of social entrepreneurs. First, the creation of public programmes, which provide counselling in doing business plans and access to initial capital (Cho & Honorati, Citation2014). Second, the development of a critical mass of non-profit organisations that enhances social enterprises’ marketing activities (Ashoka, Citation2017). Yet, while some types of support may become highly valued for communities that are very proactive, others may need a different approach. In any case, increased attention is being given to the development of this private social sector, which is being acknowledged as an engine of social transformation.

4. Research methodology

This research adopts an exploratory perspective and employs a narrative approach. Narrative inquiry is considered to be appropriated for getting insights into social investigations that deal with complex and many layered topics (Czarniawska, Citation2004; Andrews et al., Citation2008). By focusing in the constitutive role of language (verbal and non-verbal) the narrative approach emphasises people’s stories, placing them in the heart of the research. Such stories or narratives are seen as contributors to the ways people contextualise situations in terms of both how a situation is conceived (what it is considered to ‘be’), and what might be deemed to be appropriate courses of action (Toledano & Anderson, Citation2017). Therefore, in our study, versions of truth are produced in the process of narratives or counter narratives that emerge to explain, with diverse details, people’s experiences about the impact that foreign aid and the support to social entrepreneurs have to help Zimbabwe’s development. The main socio-economic aspects concerning this country and the strategies used in gathering and analysing the information are presented in the following sections.

4.1. Research setting: Zimbabwe’s economic profile

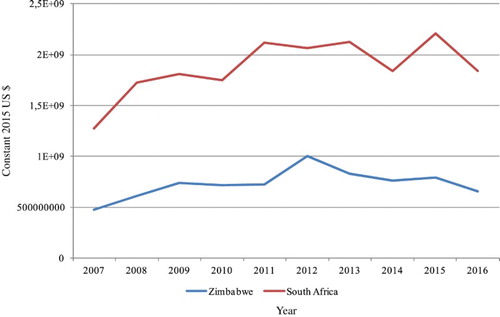

Zimbabwe is one of the lowest income countries in Southern Africa. Despite that it once enjoyed a well-developed infrastructure and financial system (Chikowore, Citation2010), its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has remained depressed for decades, declining rapidly from 2005 to 2008 and falling well below the GDP of other Southern African countries such as South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, Mozambique or Namibia. Since then it has continued to rise annually, although at a very slow pace as compared to these countries. In 2016 Zimbabwe’s GDP reached US$16 620 billion, but this was still 17 times less than its neighbour South Africa (see ).

Table 1. World Development Indicators of Zimbabwe and other Southern African’s countries (2005–16).

In terms of Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, as shown in , during the past years Zimbabwe only surpassed Mozambique, with the exception of the period 2007–9 when its figures fell. This was attributed, in part, to a deteriorating political/economic situation that led to the adoption of a multi-currency system as the national currency. On the contrary, South Africa, Botswana and Namibia have been leading the Southern Region as an indication of the performance of their economies.

Regarding the national poverty headcount ratio, the available data for 2011 coded it at 72.3 per cent (World Bank, Citation2016a), which meant that for every 100 people, 72 were living below the national poverty datum line. Besides, due to the low monthly salaries for a great part of the civil servants (normally below $500) and the continued increase of unemployment rate (more than 90% in 2016) (World Bank, Citation2016b), we might well affirm that most of the country’s citizens are currently living in a situation of worsened poverty.

Fighting poverty in Zimbabwe has been one of the goals of foreign aid. While South Africa has always received higher development assistance than Zimbabwe, the contributions to this country in the last decade (2007–16) have averaged about $729 494 000 per year (see ). Considering that Zimbabwe’s population in 2016 was about 15 million inhabitants, one can recognise that the flows of aid to Zimbabwe have been quite significant.

Figure 1. Net official development assistance and official aid received in Zimbabwe and South Africa (2007–16). Source: Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Geographical Distribution of Financial Flows to Developing Countries, Development Co-operation Report, and International Development Statistics database. oecd.org/dac/stats/idsonline.

Countries such as Germany, Sweden, Japan or Australia have been supporting Zimbabwe’s development considerably, in addition to the United Kingdom that has been the second-largest bilateral donor after the United States (see ).

Table 2. Top 10 donors for Zimbabwe (comprehensive data on total flows of aid to Zimbabwe, 2007–16, US dollars, millions (0)).

Various economic and social activities have been supported, especially in the health sector (UNICEF, Citation2015). The rural communities also benefit through some Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) projects and some efforts have been made to support entrepreneurial initiatives – including social entrepreneurial projects (Masendeke & Mugova, Citation2009). Yet Zimbabwe is still in one of the lowest positions on the ranking of ease of doing business (World Bank, Citation2018), so the need for consolidating such support seems to be evident.

4.2. Data collection and analysis

The evidence used in this article was gathered over a six-month period (November 2015 to April 2016). Following previous studies that utilised narrative framework (Silverman, Citation2000; Hamilton, Citation2006), personal contacts were used to identify potential informants. Specifically, one of the researchers who was familiar with the context maintained informal communication with several acquaintances. Two of them (a religious leader and a small enterprise owner) were key links to accessing the respondents who participated in this research. For the purpose of this study, it implied achieving a target of respondents that, in general, could give us an overall picture of what the implementation of foreign aid and social entrepreneurs’ support in Zimbabwe is entailing, not so much from an ‘expert perspective’ but from the common understanding derived from a direct or indirect experience. This meant that our ‘ideal respondents’ may not know the logic, dynamic and elements involved in the process of receiving foreign aid and social enterprise support. Ultimately, what matters was that they were aware of Zimbabwe’s experience as a country that has long been targeted as a receiver of international aid and other development measures.

In total, we collected stories from 35 individuals, including the two people known by one of the researchers. Nonetheless, apart from this exception, the respondents were not acquainted with the researchers, but they were contacted through other people who knew them. The decision about who and how many to include in our sample was purposive (Patton, Citation1990; Hamilton, Citation2006). On the one hand, a provincial basis was taken into account so as to draw up a meaningful picture from an important part of Zimbabwe. On the other, an effort was made to ensure that the data collected were relative to diverse activity profiles, so that a range of people depicting different roles was included (see ).

Table 3. Sample profile.

It took three months for one of the researchers to contact all the respondents and explain the intentions of the study. The researcher clarified that the aim was to listen to personal stories that may help us to grasp Zimbabweans’ personal opinion on how their situation – and Zimbabwe as a country – was improving or may improve with foreign aid or supporting social entrepreneurs. Nonetheless, such terms were not used but, alternatively, replaced by ‘donor community’ and ‘income generating projects for basic goods/services’, respectively, which could be clearly understood among Zimbabwe’s population.

The narrative interview was the main technique employed to collect information. As the narrative interview focuses on the respondents’ own experiences, the study did not use set scripts, but rather allowed the questions to ‘flow from the course of the dialogue’ (Thompson et al., Citation1989: 138). Respondents told their stories in different ways. Some spoke in English and some in Shona – a vernacular language also spoken by one of the researchers. Some were good storytellers, but others needed more prompting by the interviewer to get the stories. The interviews began with open ended questions and conversational devices such as, ‘Can you tell me about yourself?’, ‘Can you tell me about your daily life routines?’ and ‘Can you narrate one of your typical days?’ Then, depending on their experiences and the depth of the stories they were telling, we asked more specific questions. Some of them were: ‘Please tell me how you feel about the donor community work in your locality’; ‘Can you give me some examples?’, ‘How would you describe the role of income generating projects?’, ‘Could you tell me what may be a support alternative for you or your community if any?’ The interviews took place in different settings, such as private houses (personal and family houses), businesses premises, churches and even under trees. They lasted between 45 minutes and one hour each and were recorded and later transcribed.

A thematic approach was used for data analysis. Our tasks entailed the reading and re-reading of the transcribed interviews to give us a full understanding of the themes related to the research topic (Eisenhardt & Graebnerm, Citation2007). To this end the analysis process involved underlining sentences with the same words and ideas that had been repeated or occurred and re-occurred. Every interpretative attempt – including translations from Shona – was made to honour the spirit, imagery and tone of all the conversations and dialogues that occurred through the interviews. Moreover, to ensure credibility of our interpretations, we presented the transcripts of the quotes used in this article and our initial interpretations to some of the interviewees, asking for their comments. This also helped us to refine the data, and most importantly to ensure that the understanding was mutual. Because of the political situation in ZimbabweFootnote1 and for ethical reasons, all verbatim quotes from interviews are mentioned anonymously.

5. Research findings

5.1. Narratives on foreign aid

The narratives on foreign aid serve in many ways to support Moyo’s (Citation2009) and Easterly’s (Citation2006) critical views that although foreign aid had good intentions, it may not always be implemented in the most effective way, nor may it be well designed to produce the results intended without damaging, somehow, the recipient countries. Both themes were clearly identified in our narratives (see ).

Table 4. Themes, key issues and narratives on traditional foreign aid.

First, in terms of foreign aid’s implementation, our evidence confirmed the literature’s concerns regarding its ineffectiveness in countries with poor governance. This was recognised as the respondents recalled, in several ways, what they perceived as corrupt and/or inappropriate practices in the process of distributing foreign aid. For example, it was common to hear NGOs’ complaints to the donor sector because of their pressures to prove aid impact. The problem can be clearly perceived in the following allegations made by an NGO manager: ‘Quite often the donor sector gets impatient to see the impact on the ground, so that we, sometimes, deliver the help they give us, whether food, clothes or medicines, without an appropriate study of the situation’ (Interview 13). However, counter narratives also emerged against local NGOs, which were blamed for contributing to the poor results of foreign aid. The following quote from one of the rural unemployed interviewees is illustrative of this perception: ‘Local NGOs drive nice cars and travel overseas, so the executives must be enjoying high salaries, instead of delivering the funds received to the people with real needs’ (Interview 21). Still other interviewees stressed Zimbabwe government’s opportunistic practices and charged it for the politicisation of food aid. As one interviewed SME owner said: ‘Many people here support the ruling political party because that is the only way they can receive food aid and anyone linked with opposition parties is bound to starve to death for no food is given to them’ (Interview 30).

Second, the narratives shed light on donors’ misconceptions to designing food aid and their consequent destabilising effects in Zimbabweans’ lives. Such misconceptions and subversive effects were so vividly expressed that they often appeared to overshadow any other positive effect that food aid could have in the communities. The most commonly reported complaints were related to lack of knowledge in terms of providing appropriate food or the utilisation of feeding channels. For example, one of our interviewees who had been receiving nourishment through local aid agencies for more than 10 years made the following comment: ‘It is true that food aid has come from time to time, but the rice we receive at times from aid agencies is food that we cannot allow ourselves to eat everyday as a staple food’ (Interview 3). The interviewee’s story made it clear that the type of food that aid agencies were distributing was inappropriate; using his own words, the food was ‘too much lush’. Because they could not afford to eat normally such food, their children were not used to eating it and did not like its taste. Even though they tried to sell the donated rice to other villagers, they failed because the people around had no resources to buy it, nor did they value it as a staple food, preferring maize instead.

In addition, narratives revealed that despite that food aid had prevented many people from starving, there was also a negative feeling attached to it; over time, it had created a kind of dependency syndrome among a great part of the population. This unresolved tension was strongly expressed by one of the social entrepreneurs interviewed, who in dialogue with the researcher explained his perception of the situation through the following example:

Suppose there are monkeys living on trees near your camping site; in their context, they are enjoying themselves, since this is their normal habitat. Looking for food is normal for them and they have their own survival skills. Say a person comes to their habitat with bananas; this is luxury food that they could also enjoy it. While some monkeys may not dare to eat bananas others might eat and enjoy them. Then, the person will be able to entice monkeys to come down the trees, so that they will receive bananas from the ground, that is, from where human normal habit is. Then, one might give them bananas for some time till they get used to eating bananas while they are seated on the ground. However, in essence, that person will have changed the monkeys’ lifestyles. Therefore, the giving of bananas is changing the lifestyle of the monkeys, which may not have happened in the same way if that person had considered giving the staple food to the monkeys while they were on the trees. (Interview 26)

5.2. Narratives on social entrepreneurs’ support

A prominent aspect of the narratives on social entrepreneurs’ support is the fact that most of the interviewees could easily recognise themselves as potential beneficiaries. When telling their stories, the fact that they had received such support became less relevant, as did the issue of whether they were initially categorised as small individual business owners, unemployed or religious leaders. Rather, the important point was that most of them recognised that, in some periods, they had behaved as social entrepreneurs in the widest sense of the expression (Bornstein, Citation2007). This meant that, at times, they had undertaken initiatives to face the closest and greatest challenges in their communities by using some entrepreneurial approaches. During the interviews, when the types of support to social entrepreneurs were discussed, two typical themes were repeated: the need for a proper social entrepreneurial ecosystem and the need for investing in human and social capital (see ).

Table 5. Themes, key issues and narratives on social entrepreneurs’ support.

The need for social entrepreneurial ecosystem was mainly related to lack of basic infrastructure and services such as solar energy/generators, internet access and common medium of transport. We listened to stories that explained the inconveniences of not having electricity and a feeling of despair was evident in some instances. As one of the social entrepreneurs interviewed said: ‘I feel my business is so vulnerable at times, just because I cannot access any infrastructure that is basic. I think that solar powered invertors may solve some of the problems, at least, to reduce some vulnerability’ (Interview 28).

Linked to this problem, narratives also shed light on the importance of access to the internet, especially to small individual business owners from the city. The need for information to manage their tasks was emphasised in their accounts of trying to leave the country in search of better business and life conditions. In addition, bicycles were referred to as helpful means of transport to move easily around the villages. In this respect, one of the rural unemployed interviewees affirmed: ‘Transport is a challenge where society has food challenges so bicycles can serve communities in terms of making access to food easier’ (Interview 2).

The second prominent theme in the interviewees’ narratives, as mentioned earlier, highlighted the importance of training and knowing the right people to facilitate the social business creation process. Narratives seemed then to suggest the need for interplay of human and social capital.

In terms of human capital, the most usual comments were related to the prospect of improving the small local entrepreneurs’ competitive situation through different training measures. Some religious leaders, for example, spoke about the importance of educating for detaching from a dependency mentality and increasing self-confidence among the population. Several interviewees insisted on the need to learn to be self-sufficient through agriculture, while others stressed the need for better know-how in entrepreneurial transactions. In addition, because AIDS is one of the greatest challenges that limit human potential capabilities in Zimbabwe, knowledge about the risks of contagious diseases was also suggested as a relevant theme to include in any educational measure addressed to the Zimbabweans’ youth.

Nonetheless, important as the measures for improving human capital may be, it became clear that advances in entrepreneurial competitiveness within Zimbabwe’s social businesses sector required not only specific training but also the development of a proper social network. Underlying the comments about learning experiences that might improve people’s knowledge was the idea of increasing the connections with other economic and social agents, so that the small social entrepreneurs’ bargains may fructify. As some of the stories suggested, it seems that Zimbabweans have become more aware of the importance of putting differences aside and working from strong networks for the benefit of the whole country.

6. Discussion and conclusions

Over a number of decades, many governments and aid activists have shared a common faith that foreign aid programmes can contribute to the transformation of African countries caged in the poverty trap (Sachs, Citation2005). Yet, the interest in helping Africa by using a bottom–up approach has gained recognition in the past years (Easterly, Citation2009; Moyo, Citation2009), particularly, the support to social entrepreneurs (Masendeke & Mugova, Citation2009; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2012). The present study has made efforts to shed light on Zimbabweans’ perceptions about both foreign aid and social entrepreneurs’ support as tools aimed at helping Zimbabwe to get out of poverty.

Concerning foreign aid, from the narratives emerges a negative picture. The evidence reveals that in terms of aid implementation, the support is perceived as insufficient and ineffective, despite that some informants recognised its contribution to the improvement of their lives. Primarily, the corruptive political role in the implementation of foreign aid was stressed as one of the major problems. Respondents made it clear that while Zimbabwe lacks an accountable and transparent governance, it is probable that the good intentions of foreign aid ends up in failure, bearing out what most critics have noted (Easterly & Pfutze, Citation2008; Moyo, Citation2009; Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2011). But then, respondents also complained about the donors because they disregarded local customs. In this respect, our evidence confirms the importance of considering the recipients’ social customs in aid programmes (Sen, Citation1999; Altaf, Citation2011) and how the fact of disregarding them may produce destabilising effects in local people’s lifestyles (Ouattara, Citation2007). The narratives raise concerns with the way in which Zimbabweans’ idiosyncrasy and culture are left out of the aid conceptual framework, especially when foreign aid takes the form of food aid. Misconceptions from donors (e.g. giving food to the poor is always helpful) can have unintended and unfortunate effects. This, in fact, raises questions with respect to what some aid does; whether it is meant to improve people’s situation or to change their natural condition. As the narratives seem to suggest, it is possible that food aid – or any other modality of foreign aid – might change the recipient people to be who the donors expect them to be; but the same people may then fail after that process of change. However, while they might fail they may not go back to being as the original group.

Concerning the support to social entrepreneurs, the interviewees’ stories suggest that there is need for providing aggregate assistance on social entrepreneurship in broad terms, as it is articulated in recent literature related to entrepreneurial ecosystems (Stam, Citation2015). The narratives revealed a gap between the current individual support approach that prevails in Zimbabwe (e.g. personal financial loans) and the existence of an appropriate context – especially adequate infrastructure – for people to create and work from formal social businesses. Relating to a more social business-friendly context, the emphasis was also put into expanding people’s freedom of choice and action; evidence showed, for instance, the concern for expanding opportunities to get knowledge and contacts that could help to create innovative social initiatives. This suggests that local people regard not only economic aspects of development but also its human and social dimensions (Sen, Citation1999; Altaf, Citation2011). Indeed, there was something about the whole rhetoric that pointed out towards an empowerment-oriented support approach. Thus, it would be necessary to consider both context – as a space with history and idiosyncrasy – and local people – as capable people although with needs of developing their capacities – for social entrepreneurs could lead the paths for Zimbabwe’s development.

Despite these clues, it is difficult to draw outright conclusions about the best way to help Zimbabwe to get out of poverty. But one thing seems to be clear: since Zimbabwe’s poverty involves complex and interconnected factors, it is almost impossible to be solved with a single strategy from outside. The narratives have shed some light on the roles that different development measures might play in Zimbabwe. For instance, the requirements for ordinary ongoing human life in devastating situations may require direct help that foreign aid may well provide if the weaknesses noted above are considered. Alternatively, the social transformation that Zimbabwe’s poor economy calls for demands the improvement of its productive capacity, which implies improving the entrepreneurial context and empowering potential social entrepreneurs.

Finally, the qualitative approach adopted in this study also calls for modest interpretations of the results. However, it is worth mentioning that while the sample of the respondents was purposive (Patton, Citation1990; Hamilton, Citation2006), their stories often embedded a general idea about what is experienced among important parts of the country. In fact, the strength of the analysis is that the key turning points of the narratives exhibit thickness of expectation and a strong presence of the ‘we’. In this sense, our evidence has also shown the value of narrative as a tool for uncovering and understanding hidden elements of foreign aid and the support to social entrepreneurs. Adopting this approach has permitted us to look beyond the traditional samples. Indeed, new stories might be narrated in other contexts. Thus, further studies may continue to deepen these qualitative insights, while others complement them from a quantitative and confirmatory point of view.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 There is concern about speaking openly of issues that may affect political decisions in Zimbabwe. The dominant ruling party has led the country with the same president, Robert Mugabe, since its independence in 1980. Yet, an emergency situation was declared on 14 November 2017, when the army took over the city of Harare with the objective of removing the president. Such goal was peacefully achieved one week later, on 21 November; yet the new political future remains uncertain.

References

- Altaf, SW, 2011. So much aid, so little development: Stories from Pakistan. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Andrews, M, Squire, C & Tamboukou, M, 2008. Doing narrative research. Sage, London.

- Ashoka, 2017. Ashoka support networks. https://www.ashoka.org/en/program/ashoka-support-network-0. Accessed 15 February 2018.

- Austin, J, Stevenson, H & Wei-Skillern, J, 2006. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30(1), 1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x

- Banerjee, A & Duflo, E, 2011. Poor economics: A radical rethinking of the way to fight poverty. Public Affairs, New York.

- Barrett, CB, 2010. Measuring food insecurity. Science 327(5967), 825–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1182768

- Becerra, O, Cavallo, E & Noy, I, 2014. Foreign aid in the aftermath of large natural disasters. Review of Development Economics 18(3), 445–60. doi: 10.1111/rode.12095

- Bornstein, D, 2007. How to change the world: Social entrepreneurs and the power of new ideas. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Chikowore, G, 2010. Contradictions in development aid: The case of Zimbabwe. http://www.realityofaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/ROA-SSDC-Special-Report4.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2018.

- Cho, Y & Honorati, M, 2014. Entrepreneurship programs in developing countries: A meta regression analysis. Labour Economics 28(C), 110–30. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2014.03.011

- Collier, P, 2007. The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Czarniawska, B, 2004. Narratives in social science research. Sage, London.

- Easterly, W, 2006. The white man's burden: Why the West's efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Easterly, W, 2009. How the millennium development goals are unfair to Africa. World Development 37(1), 26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.02.009

- Easterly, W & Pfutze, T, 2008. Where does the money go? Best and worst practices in foreign aid. Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(2), 29–52. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.2.29

- Easterly, W & Williamson, C, 2011. Rhetoric versus reality: The best and worst of aid agency practices. World Development 3(11), 1930–49. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.027

- Eisenhardt, KM & Graebner, ME, 2007. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal 50(1), 25–32. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Fisher, J, 2015. Does it work? –work for whom? Britain and political conditionality since the Cold War. World Development 75, 13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.005

- Giella, A, 2016. An introduction to U.S. foreign aid and international food aid programs. Nova science publishers, New York.

- Gupta, S, Clements, B & Tiongson, ER, 2004. Foreign aid and consumption smoothing: Evidence from global food aid. Review of Development Economics 8(3), 379–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9361.2004.00239.x

- Hamilton, E, 2006. Whose story is it anyway?: Narrative accounts of the role of women in founding and establishing family businesses. International Small Business Journal 24(3), 253–71. doi: 10.1177/0266242606063432

- Haugh, HM & Talwar, A, 2016. Linking social entrepreneurship and social change: The mediating role of empowerment. Journal of Business Ethics 133(4), 643–58. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2449-4

- Huybrechts, B & Nicholls, A, 2012. Social entrepreneurship: Definitions, drivers and challenges. In Volkmann, CK, Tokarski, KO & Ernst, K (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship and social business: An introduction and discussion with case studies (pp. 31–48). Springer-Gabler, Wiesbaden.

- Ilorah, R, 2008. Trade, aid and national development in Africa. Development Southern Africa 25(1), 83–98. doi: 10.1080/03768350701837796

- Jayne, TS, Strauss, J, Yamano, T & Molla, D, 2002. Targeting of food aid in rural Ethiopia: Chronic need or inertia? Journal of Development Economics 68(2), 247–88. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(02)00013-5

- Karanda, C & Toledano, N, 2012. Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: A different narrative for a different context. Social Enterprise Journal 8(3), 201–15. doi: 10.1108/17508611211280755

- Kerlin, JA, 2009. Social enterprise: A global perspective. University Press of New England, Lebanon.

- Ligthelm, AA, 2008. A targeted approach to informal business development: The entrepreneurial route. Development Southern Africa 25(4), 367–82. doi: 10.1080/03768350802316138

- Littlewood, D & Holt, D, 2015. Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: Exploring the influence of environment. Business and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315613293

- Masendeke, A & Mugova, A, 2009. Zimbabwe and Zambia. In Kerlin, JA (Ed.), Social enterprise: A global perspective (pp. 114–38). University Press of New England, Lebanon.

- Mawdsley, E, Murray, WE, Overton, J, Scheyvens, R & Banks, G, 2018. Exporting stimulus and “shared prosperity”: Reinventing foreign aid for a retroliberal era. Development Policy Review 36(51), 25–43. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12282

- Molenaers, N, Dellepiane, S & Faust, J, 2015. Political conditionality and foreign aid. World Development 75, 2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.001

- Moyo, D, 2009. Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is a better way for Africa. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

- OECD, 2005. The development effectiveness of food aid. Does tying matter? OECD publishing. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3043.pdf. Accessed 13 February 2018.

- Ouattara, B, 2007. Foreign aid, public savings displacement and aid dependency in Côte d’Ivoire: An aid disaggregation approach. Oxford Development Studies 35(1), 33–46. doi: 10.1080/13600810601167579

- Patton, MQ, 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage, Newbury Park.

- Petterson, J, 2007. Foreign sectoral aid fungibility, growth and poverty reduction. Journal of International Development 19, 1074–98. doi: 10.1002/jid.1378

- Rivera-Santos, M, Holt, D, Littlewood, D & Kolk, A, 2015. Social entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa. The Academy of Management Perspectives 29(1), 72–91. doi: 10.5465/amp.2013.0128

- Sachs, J, 2005. The end of poverty: Economic possibilities for our time. The Penguing Press, New York.

- Seelos, C & Mair, J, 2009. Hope for sustainable development: How social entrepreneurs make it happen. In Ziegler, R (Ed.), An introduction to social entrepreneurship -voices, preconditions, contexts (pp. 228–46). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, Cheltenham.

- Seelos, C, Ganly, K & Mair, J, 2006. Social entrepreneurs directly contribute to global development goals. In Seelos, C, Ganly, K & Mair, J (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship (pp. 235–75). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Sen, A, 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Silverman, D, 2000. Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. Sage, London.

- Sinyolo, S, Mudhara, M & Wale, E, 2017. The impact of social grant dependency on smallholder maize producers’ market participation in South Africa: Application of the double-hurdle model. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 20(1), 1–10. doi: 10.4102/sajems.v20i1.1474

- Stam, E, 2015. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies 23(9), 1759–69. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

- Thompson, CJ, Locander, WB & Pollio, HR, 1989. Putting consumer experience back into consumer research: The philosophy and method of existential phenomenology. Journal of Consumer Research 16: 133–146. doi: 10.1086/209203

- Toledano, N & Anderson, A, 2017. Theoretical reflections on narrative in action research. Action Research. https://doi.org/10.1177.1476750317748439

- UNICEF, 2015. Annual report Zimbabwe. https://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/Zimbabwe_2015_COAR.pdf. Accessed 21 February 2018.

- Urban, B, 2008. Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: Delineating the construct with associated skills. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 14(5), 346–64. doi: 10.1108/13552550810897696

- WFP, 2011. Eight examples of effective food aid. World food programme. http://www.wfp.org/stories/eight-examples-effective-food-aid. Accessed 13 February 2018.

- World Bank, 2016a. Poverty headcount ratio. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC Accessed 2 March 2016.

- World Bank, 2016b. Unemployment data 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.PRIM.ZSAccessed 2 March 2016.

- World Bank, 2018. Doing business. Measuring business regulations. http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/zimbabwe. Accessed 21 February 2018.

- Zahra, SA, Gedajlovic, E, Neubaum, DO & Shulman, JM, 2009. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing 24(5), 519–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.007