ABSTRACT

The emissions of greenhouse gases together with other anthropogenic activities has caused a change in global climatic conditions with corresponding negative effects on agricultural productivity, biodiversity and other socio-economic indices. Studies reveal that the impacts of climate change are felt most severely by the vulnerable, who have fewer adaptive capacities. In Africa, for example, little is known about local narratives on the ‘causes’ of climate change, and how such narratives influence climate change coping and adaptation strategies in specific local settings. Where do the ‘local’ and the ‘global’ intersect in the search for effective coping measures – and do they? Using a qualitative approach, this paper reveals how local conceptions of climate change appear to be rooted in ‘politics’ and spiritual forces. The paper highlights not only the major points of divergence between local interpretations and ‘Western’ conceptions about climate change, but also important areas of convergence between the two ideational domains.

1. Introduction

The numerous unprecedented changes in weather patterns, observed since the 1950s, have led to widespread consensus about a changing world climatic system (IPCC, Citation2013). The amounts of snow and ice have diminished drastically, sea levels have risen and the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have increased, leading to changes in precipitation and rainfall patterns (IPCC, Citation2007, Citation2013). The emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere together with other anthropogenic activities have caused a change in global climatic conditions with corresponding negative effects on agricultural productivity, biodiversity, ecosystems, human health and other socio-economic indices all over the world (IPCC, Citation2007).

Current global, continental and local discussions on climate change are hugely dominated by the nature and degree of climate change impacts on communities, as well as the various adaptation strategies available to mitigate such impacts (Parry et al., Citation2004; Voigt et al., Citation2004). According to available literature, the missing link between climate-induced impacts and their coping strategies championed so far, especially in the developing world, is the lack of idiographic elements and the interdisciplinary aspects of climate change coping and adaptation policies. Such idiographic nuances and interdisciplinary approaches could cover, among other things, the local interpretations and practices in handling some of the impacts of climate change. This paper goes beyond the orthodoxies of climate change science, especially the dominant discourses pertaining to the causes of climate change, to look at some of key socio-cultural interpretations some rural and peri-urban residents in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa give to climate change. This is achieved by first gauging the level of climate change awareness among community members, before interrogating the meanings residents give to climate change as a phenomenon and how such socio-cultural idiographics and people’s understanding of climate change could influence their response strategies thereof.

2. Climate change evidence: a global panoramic view

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) fourth and fifth assessment reports (AR4 – 2007; AR5 – 2013) reveal that global temperatures and sea levels have been on the rise over the past ten decades, while precipitation and rainfall patterns have been fluctuating and causing many forms of socio-economic problems globally. These views are shared by the African Climate Policy Centre (ACPC, Citation2014), which posits that climate change is widely acknowledged as the most defining challenge of the twenty-first century. Evidence from climate-sensitive indicators such as tree rings, ice cores and boreholes indicates that during pre-historic and medieval times, global warming stood at only 0.05°C per century (Pittock, Citation2009). For instance, at the end of the last glaciation (the period of ice spanning over some 10 000 years ago), the average rate of warming was 5.0°C, representing approximately 0.05°C per century. However, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, global temperatures started rising, and have since kept a rising trend to date (Pittock, Citation2009). Evidence gathered from available natural archives and various forms of temperature estimates by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) indicate that indeed the pre-historic and medieval periods experienced lower temperature values than the twentieth century alone (WMO, Citation2013).

This is corroborated by the IPCC, which notes that temperatures have risen globally at an average of 0.74°C for the past century, with the second half of the century being twice as warm as the entire century (IPCC, Citation2007, Citation2013). Similarly, Pittock (2009:3) estimates the rate of warming over the next century to be more than 5.0°C, which is 100 times more than the warming experienced during the glaciation period. With an estimated increase in global mean temperature and a decrease in average rainfall volumes in the twenty-first century, it is further projected that evaporation would increase globally (see IPCC, Citation2007, Citation2013; Pittock, Citation2009). Despite the difficulty in predicting evaporation rates in specific local areas, it is estimated that globally climate change would adversely affect the water cycle in the twenty-first century, leading to a negative change in the world hydrological regime (Kay & Davies, Citation2008). With a negative change in the global hydrological regime, coupled with increased wind speed and temperature values and declining rainfall volumes, livelihoods are expected to be negatively affected – particularly agriculture – in less developed countries with less developed agricultural infrastructure (Chu et al., Citation2010; Zinyengere et al., Citation2013:120). Literature again shows that since the 1960s snow cover has experienced a decrease of approximately 10%, whilst the Antarctic Peninsula area – the region of ice deposits – has experienced fluctuations in sea-ice levels due to rapid regional warming, leading to a disintegration of several large semi-permanent ice shelves attached to the mainland (IPCC, Citation2001, Citation2007; Pittock, Citation2009). This melting ice is partly contributing to rising sea levels. For example, between 1993 and 2008 global sea levels rose by about 3 mm as a result of factors such as volcanic dust, surface warming and melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, with the net effect of coastal erosions in some of the affected regions (Leary et al., Citation2009).

In sub-Saharan Africa, Shinoda et al. (Citation1999) argue that the droughts in the 1970s and 1980s on the continent, for instance, were primarily characterised by a reduced frequency of rainfall events and general precipitation activities. In a related analysis, Nicholson & Kim (Citation1997) note that the pattern of declining precipitation on the continent since the beginning of the twentieth century is apparent throughout the Sudan-Sahel zone including the Ethiopian Plateau, while the Southern Africa region has remained relatively wet, amidst isolated drought events. Studies project that the world is at risk of experiencing changes in annual average precipitation patterns, increased hail storms, more intense rains leading to flooding, and longer dry spells all because of climate change (Johnston & Schultze, Citation2010). The next section of the paper looks at the scientific explanation of the causes of climate change.

3. What causes climate change? A brief scientific interpretation

As sociologists, the authors of this paper do not have the competence to scientifically explain or critique what is causing changes in global climatic systems. However, drawing on literature from various sources, it is highlighted that apart from natural variations and events, the fast changes in global climatic conditions are anthropogenically induced through modern manufacturing activities, human settlement, deforestation and crude farming practices (IPCC, Citation2013). Through such human activities, some harmful gases called greenhouse gases are emitted into the atmosphere, which react with other natural processes to cause changes in global climatic conditions (Ragab & Prudhomme, Citation2002). Some of these gases, which when emitted into the atmosphere act as a wide ‘blanket’ covering the earth’s surface and obstructing infrared radiation, are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), hydrogen sulphide (H2S), nitrous oxide (N2O), nitrogen oxides (NO and NO2), sulphur dioxide (SO2), chlorofluorocarbons (mainly CFC11 and CFC12), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs, general formula CxFy) and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) (IPCC, Citation2007, Citation2013; Pittock, Citation2009). The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO, Citation2012) indicates that the collective contribution of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and chlorofluorocarbons accounts for approximately 96% of the world‘s radiative forcing. Radiative forcing refers to the net change in the energy balance of the earth system due to some imposed perturbations as a result of greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC, Citation2013:680). These gases are closely linked to anthropogenic activities in the biosphere, soil, oceans and in various industrial processes and when emitted into the atmosphere react with other chemicals to disrupt various weather events, leading to changes in world climatic conditions. However, critics argue that future climatic projections cannot be based solely on future emissions and concentrations of greenhouse gases; rather, the sensitivity of the global weather to the increased concentration levels of some of these gases, the warming and cooling capacity of the natural environment and processes, and the changing trend in atmospheric dust from volcanoes should also be taken into serious account (Ruddiman, Citation2003; James, Citation2005). This notwithstanding, anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases have increased the atmosphere’s ability to absorb the earth’s outgoing infrared radiation, which has caused a worldwide trend of rising temperatures and other forms of changes in climate conditions (DST Citation2011). Thus land degradation and deforestation are negatively affecting the environment, which is gradually losing its resilience and capacity to sequester environmentally hazardous gases (SADC & UNEP, Citation2010:16).

4. Conceptual framework

Climate change impact coping and adaptation strategies in a given locality are to some extent influenced by the level of vulnerability within a given setting and the meanings attached to climate change as a phenomenon. According to Kelly & Adger (Citation2000:328), vulnerability is the ability or inability of individuals and social groupings to respond to, in the sense of cope with, recover from or adapt to, any external stress placed on their livelihoods and well-being. Eriksen & Kelly (Citation2007) see vulnerability as a set of socio-economic, political and physical factors that determine the amount of damage a given event will cause (Eriksen & Kelly, Citation2007:499), while Hufschmidt (Citation2011) sees vulnerability as ‘the conditions determined by physical, social, economic and environmental factors or processes which increase the susceptibility of a community to the impacts of hazards’ (Hufschmidt, Citation2011:623). Hufschmidt’s assertion corroborates Blaikie et al.’s (Citation1994) submission that vulnerability must always be linked with a specific hazard or set of hazards so that vulnerability and exposure in the context of climate change become inseparable. This means that vulnerability to climate change and other environmental related events are somewhat socially, economically and politically constructed and not natural. Social construction of vulnerability as used here refers to how different socio-economic and political characteristics, processes or trends (including knowledge on climate change) influence levels of vulnerability (Kelly & Adger, Citation2000:329). In other words, vulnerability is a function of the sensitivity and exposure of a system to changes in climatic conditions (i.e. the degree to which a system will respond to a given change, including both beneficial and harmful effects, based on knowledge and understanding of such changes), and the ability to adjust the system to enable it cope and adapt to hazards that come with changes in climate (CSIR, Citation2011).

Coping, as used in this paper, refers to a short-term and immediate response to unusual climate or weather events (Berkes & Jolly, Citation2001). According to Davies (Citation1993), coping mechanisms and strategies are a bundle of people‘s immediate responses to adverse effects of climate-induced events. Such mechanisms and strategies often take the form of emergency and panic responses of individuals and households to abnormal weather- and or climate-induced events. Adaptation on the other hand is used here to mean the adjustment in human and to some extent natural systems in response to actual or expected climate stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities (IPCC, Citation2001: cited in SADC & UNEP, Citation2010:25). Such adaptive systems include adjustment in structures to influence processes and practices that can help to counterbalance or moderate the dangers caused by climate variability and finally take advantage of such damage for growth. The key distinction between coping and adaptation, in the context of climate change discourse, is that coping, by definition and application, is a temporary response to climate-induced impacts on livelihoods without any fundamental or structural changes to systems and institutions. Adaptation, on the other hand, entails long-term strategies and permanent structural changes to sources of livelihoods as a means of forestalling future adverse effects of climate change on livelihoods (Davies, Citation1993). Coping with climate change adverse effects therefore means acting to survive in the context of prevailing climate condition, while adaptation entails changing of socio-economic systems, institutions and productive activities to protect livelihoods from future climate events. The two kinds of responses (coping and adaptation) may overlap in one way or the other, but their primary separation point is that in most cases coping mechanisms develop into adaptive strategies.

Drawing on this premise, this paper again uses human capital to analyse how knowledge on climate change and local interpretations, to some extent, can influence coping and adaptation processes. According to Moser (Citation1998, Citation2006) human capital refers to investments in education (both formal and informal), health and nutrition of individuals for sustainable growth and development. Relating human capital development and its utilisation to climate change coping measures, Muttarak & Lutz (Citation2014) argue that the extent to which climate-related events will increase human misery in the future partly depends on people‘s knowledge and understanding of climate change. Thus, to build a long-term resilience against the dangers of climate change – particularly in developing countries – the onus lies on individuals, families, societies and nations to strengthen human capacity through knowledge. Human capital, which centrally revolves around knowledge acquisition through education (both formal and informal), can thus play a crucial role in ameliorating some of the negative impacts of climate and extreme weather events in various ways. Lutz & Skirbekk (Citation2013) indicate that climate education is one of the primary ways through which individuals and families can acquire knowledge, competencies and skills that could boost their coping and adaptive capacity. In other words; climate knowledge, general life skills and abstract thinking can give better understanding and the ability to internalise risk information about weather forecast and warning messages (Muttarak & Lutz Citation2014:43). Thus when disaster occurs (in this case, climate-related disasters), ‘climate-educated’ individuals might be more ready to respond and act upon the event than their ‘uneducated’ counterparts. Again, Burchi (Citation2010) indicates that education increases the acquisition of knowledge and selection of priorities. This enhances one’s ability to plan for the future and improves one’s sense of judicious allocation of scarce resources – one of the key elements in climate change adaptation strategies.

Finally, it is highlighted that a good human capital base (knowledge) influences people’s risk and vulnerability perceptions. If people perceive their risk with regard to climate-related disasters to be real by virtue of their climate education they are more likely to plan for the occurrence of such risks and cope accordingly when they do occur. Risk awareness through education can contribute immensely towards climate change risk and vulnerability reduction (Burchi, Citation2010). Human capital is therefore important in assessing how people‘s awareness about climate change, vis-à-vis local interpretations of the phenomenon, can influence their coping and adaptation strategies in rural and peri-urban South Africa.

5. Methodology

This paper is based on a study that set out to assess, firstly, the level of climate change awareness in the study communities and, secondly, the kind of interpretations local residents give to climate change as a phenomenon and how such interpretations could influence climate change coping and adaptation strategies in the study communities. The study triangulated different qualitative data collection methods to validate the results of the study. The qualitative approach adopted (using focus-group discussions, observations, questionnaires and various interviews) helped the researcher to access the meanings embedded in local idiographic narratives regarding climate change, and how such interpretations could influence local coping and adaptation strategies. A total of 388 respondents participated in the study (a figure at which a theoretical saturation point was reached). Strauss & Corbin (Citation1998:212) indicate that theoretical saturation occurs when the researcher establishes that no new or relevant data seem to be emerging from the respondents, and that enough applicable information has been gathered to satisfactorily answer the research questions. The respondents were selected through a combination of probability (simple random) and non-probability (purposive) sampling methods. The focus persons for the questionnaire administration and interviews were residents (male or female) older than 40 years. It became evident during the focus-group discussions that local and cultural interpretation of climate change is not general knowledge, but is related to the length of time a person has been living in an area, direct experience and the socio-cultural embedment of the person. The older persons (40 or above) were found to capture these key variables – long-term direct experience and socio-cultural embedment – hence their appropriateness. As a qualitative study, the selection of the sample size was not based on established statistical methods and procedures; it was rather determined by the principle of theoretical saturation. A content-analysis process was used to analyse the data by first coding the major themes that emerged. It is important to note that data were not analysed along gender, age or racial lines as those variables constitute another ongoing study in the province.

5.1. The study site

The study area falls within latitude 32′47–33′46 S and longitude 25′29–27′59 E (an area which covers East London and Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa) (SAWS Citation2014). The study communities around East London were Jongilanga, Zozo, Tuba, Phindweni, Phumlani and the Ncera villages (villages 2–7). In Port Elizabeth, the selected communities were Kwanobuhle, Tireville Lapland and Vastrap. Socio-economically, the Eastern Cape Province is one of the poorest regions among the nine provinces of the country, with less than 15% of the total provincial population having an educational level higher than secondary school (Stats SA, Citation2011; Government of SA, Citation2013) – a factor that will come up later in the discussion section. The total population of the province is 6 562 053. Out of this total population, 78.8% are black IsiXhosa-speaking people (amaXhosa), 10.6% are Afrikaans-speaking people (Afrikaners and Coloureds), 5.6% are English-speaking people (mostly Whites), and the remaining 5% constitutes other minority ethnic groups including foreign nationals residing in the province (Government, Citation2013:5). This makes Xhosa the dominant culture in the province.

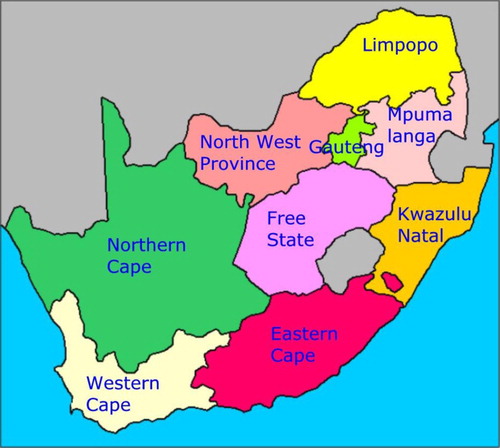

Apart from agriculture, the rest of the provincial economy centres on Port Elizabeth and East London. The metropolitan economies of Port Elizabeth and East London are based primarily on manufacturing, with the most important being automotive manufacturing. The peri-urban settlements serve as a cheap labour hub for the industrial sector in the cities as they are the migration endpoint for both city out-migrants (returnees from the central urban areas) and rural in-migrants (first time migrants from the rural areas) (Iaquinta and Drescher Citation2000). The comparatively poor socio-economic characteristics of rural and peri-urban Eastern Cape residents – whose life, state of mind and culture revolve around land, livestock, cropping, natural resources, social relations and communal solidarity – make them more vulnerable to climate change impacts, hence the critical need to measure residents’ interpretations of climate change against coping and adaptation strategies. is of South Africa, showing the Eastern Cape Province.

Map 1. A Map of South Africa indicating the Eastern Cape Province. Source: www.places.co.za.

6. Results

As mentioned earlier, the paper sets out to analyse the socio-cultural idiographics that shape, first, the understanding and interpretation of climate change as a phenomenon and, secondly, the response to coping and adaptation to climate change in rural and the peri-urban Eastern Cape of South Africa. This analysis is presented under the following themes as emerged from the study: climate change awareness, local climate change interpretations, climate change and religious interpretation and climate change and political interpretation.

6.1. Climate change awareness

The study found that people have noticed changes in climatic conditions in one way or another. Some of the observed changes mentioned by respondents include erratic precipitation and rainfall patterns accompanied by an unexplained wind speed and general decrease in year-on-year rainfall volumes, a new weather pattern with glaring inter- and intra-seasonal weather variations, a new trend of the climate system characterised by extreme weather conditions and temperature values and so on. All these changes, respondents indicated, have negatively affected local agriculture, human settlement and sanitation, ecosystems and livelihoods. A 63-year-old female respondent, Zozo, for example, gave her understanding of climate change as follows:

It is all about erratic rainfall patterns, extremely cold temperatures during winter and extremely hot temperatures during summer. We experience strong winds throughout day and night, which was not the case in the olden days. We even get heavy rains during winter nowadays, and less rains during summer, which was not the case when we were young. We know this area to be a summer rainfall region and not a winter rainfall zone, but things have changed now, why? It is all because of climate change, and that is my understanding.

6.2. Local climate change interpretations: the converging and diverging points

The study found that, given the widespread observations and awareness of the changing local and global climatic conditions, people give different interpretations or explanations of the factors underlying climate change. Out of the total 388 respondents, 139 (35.8%) gave interpretations of climate change causes that are aligned to global scientific explanations of climate change, whilst the remaining 249 (64.2%) attributed the causes of climate change to spiritual, religious, political and neo-liberal forces.

To support the scientific interpretations of climate change by residents, a 69-year-old retired automobile industry worker in the Holomisa section of Kwanobuhle shared his observations and life experiences regarding climate change as follows:

To start with, there are so many changes in climatic conditions today as compared to when I moved into this community in 1971. What is more worrisome to me is the total volume of rainfall in a year and the pattern. What I have noticed these days is that, sometimes it rains heavily for the whole week causing a lot of damage to houses, shacks, cars, animals, gardens, and even drainage and sewerage facilities. After that, we sometimes wait for more than two months without another rain. Again, I have noticed that the weather is sometimes abnormally warm these days. This was not the case when we were growing up. During our days, when it is rainy season, God made sure that He spread the rains over a reasonable period, which was good for both crop and animal production. However, these days, which you people call the days of civilization [referring to the researcher], things have changed so much including climatic conditions. I believe it is because of these factories, cars and heavy machines all over. Sometimes you will wake up in the morning to see a cloud of smoke from the factories covering everywhere. All these are blocking the rains and warming the environment every day.

6.3. Climate change: a religious interpretation

Contrary to the above, the majority of the respondents (64.2%) hold diverging views on the causes of climate change ranging from traditional and ancestral belief systems, Christian doctrines, neocolonialism/neoliberalism to local political gimmicks. It emerged that despite levels of globalisation, with its accompanying rate of information sharing, some people in the Eastern Cape of South Africa (especially in the rural areas) still believe and trust that changes in global climatic conditions are the function of supernatural forces. As many as 68 respondents (representing 17.5% of the total sample) attributed climate change and its associated negative impacts on livelihoods to traditional spiritual forces. A 65-year-old traditional leader in Ncera village 6 stated that:

We are experiencing these funny climatic conditions these days because all the protective spirits around us are angry and they are deserting us. I call the whole climate situation funny because we don’t get rains when we need rains, but it rains heavily when we least expect rains. Again, it sometimes gets hot in winter as if we are in summer and gets cold in summer as if we are in winter. All these are signs to show that the spirits are not happy with us. You people are young and stay in the city so you will not know this, but let me tell you this today maybe I will not be alive the next time you visit this village. There is a female spirit or goddess we call uMamlambo (the mother of the sea or a river, or a dam, or a lake – depending on where she resides) who takes care of the water needs of all people who depend on such water bodies. Unfortunately, the Mamlambo’s of the world today are now very angry with us because people are now encroaching river bodies, lakes, dams, streams and even the sea for all manner of reasons. That is why there are tsunamis, hurricanes and floods. They are telling us to move away.

My conclusions on these funny changes are that the gods and the supernatural powers are angry with us. In the olden days, there was a traditional practice called Ukukhonga. Ukukhonga was a practice whereby the whole community will go to the mountains to pray to God and offer sacrifices to the gods, the spirits and the ancestors to beg for rains. Unfortunately, Ukukhonga does not work these days because the ancestors and the spirits are all angry with us.

Before the Europeans came here to invade our land and culture, we respected and worshipped our ancestors and uQamata (a traditional ‘God’), and they also took good care of us. Today, we have lost total respect for them because of the Whiteman and his modern civilization. The question is, how can we have rains when the ancestors and uQamata are not happy with us? They are angry with us because we have abandoned them in favour of somebody else’s ancestors. How can we abandon people who lived and ate with us before they died, and accept someone else’s ancestors whom we did not even know when they were alive? Jesus, Moses, Joshua, Abraham and the rest, are they also not ancestors? How can we worship Jewish ancestors and turn back to say African ancestral worship is not good? Let them punish us for the neglect.

Speaking from a Christian perspective and guided by the teachings of the Bible, 91 different respondents (23.5% of the total sample) believe that everything in the universe is part of God’s creation and strictly controlled by His powers. Their understanding and interpretation are that climate change is a punishment from God in atonement for the sins, misconducts and ‘immoralities’ of humankind. A 51-year-old woman in Ncera village 3 who combines her subsistence farming with local church activities said:

Hmmm, this whole issue of prolonged droughts, floods all over the world, tsunamis and hurricanes because of changes in global weather and climatic conditions worries me day and night. Sometimes I go down on my knees and cry to God to forgive us our sins because we do not know what we are doing. My children [referring to the researcher and his assistants], we are experiencing all these funny climatic conditions worldwide because of our sins. If you do not believe me, when you get back to your school, ask your teachers to read the book of the Romans 3:23. The Bible says we have sinned so much to the extent that God’s glory is no longer with us.

6.4. Climate change: a political interpretation

The remaining 10.8% of the respondents attribute climate change to political issues. They believe that the ‘uproar’ surrounding climate change is one of the antics of the neocolonialists with their neoliberal ideologies. To them, the whole issue of climate change is another cunning and subtle strategy by the Western powers to subdue poor countries into another form of ‘economic colonialism’. In their view, whatever is happening to global climatic conditions today is an issue of cyclical weather events which have happened before, and therefore is not a new phenomenon. Probably, their line of argument is informed by the political history of the country and as a result most black communities still see anything Western as evil, albeit not being the focus of this article.

7. Discussion

Current global, continental and local discussions on climate change are hugely dominated by the nature and degree of climate change impacts on communities, as well as the various ‘scientific’ adaptation strategies available to lessen such impacts (Parry et al., Citation2004; Voigt et al., Citation2004), without giving much attention to the social dimensions of the phenomenon. Going beyond the orthodoxies of climate change science to highlight the sociological interpretations of climate change in various parts of Africa is important as the successful implementation of climate change coping and adaptation policies in the continent has to first start with changing the mindset of the people on climate change as a phenomenon.

Given the low levels of education in the Eastern Cape Province, where less than 15% of the total provincial population has an educational level higher than secondary school (see Stats SA, Citation2011), the comparatively low scientific knowledge about climatic issues is understandable. However, the strong attachment of climate change to religious, traditional and political forces by most of the people in the province (particularly rural residents) should be a major concern to both local and provincial policy-makers in the context of managing climate change and its related impacts. Such religious and spiritual interpretations of climate change could negatively impact people’s preparedness to accept modern climate change coping and adaptation measures. Most rural residents of the province perceive climate change as not real or scientific. Again, people still believe that anthropogenic factors and scientific explanations as proffered by experts have nothing to do with climate change, but rather climate change is caused by divine authority and some supernatural powers and forces. The core argument here is that, influenced by such perceptions and interpretations, most local residents across Africa with similar perceptions could remain impervious to ‘non-spiritual’ and ‘non-religious’ coping and adaptation strategies to climate change impacts irrespective of their scientific potency. The paper highlights that there is a gap between locally held perceptions and interpretations about climate change and what the realities of the phenomenon are in Africa.

People see climate change as a physical calamity caused by spiritual forces – it could be said that most residents would be more willing to accept climate change coping and adaptation strategies that are closely related to their traditional beliefs and religious doctrines. This means that lack of appropriate climate change education platforms to change the entrenched spiritual and political meanings attached to the realities of climate change could constrain the successful management of climate change in the study communities and communities alike across Africa. People’s proper understandings of climate change as a phenomenon and its knowledge dissemination are critical in coping and adapting to climate change. For one thing, they (knowledge and its dissemination) are part of the key components of climate adaptation policies in local settings, as they can fundamentally compel or constrain political, social and economic actions to address local climate change risks. For instance, good understanding of climate change and its related issues could guide local farmers in making certain decisions relating to when to plant crops and what to plant as well as how various economic activities are organised in those communities.

8. Conclusion

Climate scientists have revealed that the planet earth is warming and changing at an alarming, unprecedented and destructive rate. Among the key climate variables affected by climate change are temperature, rainfall, wind speed and precipitation patterns, leading to widespread melting of ice shelves, increased evaporation, droughts, storm surges, volcanic eruptions and rising sea levels. Agriculture, biodiversity, ecosystem, human health, infrastructure and other sensitive aspects of socio-economic lives of societies are negatively affected globally. Human activities are identified by climate scientists as the primary causes of the changes in global climatic conditions through the emission of greenhouse gasses, especially carbon dioxide.

Despite the scientific explanations of climate change provided by experts, this paper demonstrates that some individuals across various rural and peri-urban settlements in the Eastern Cape of South Africa hold contrary views about the phenomenon. Such individuals see climate change as a physical calamity caused by spiritual forces, even though some of them agree with the scientific interpretations of climate change. That section of the population (those who agree with the scientific explanation of climate change) may have been ‘academically’ enlightened through access to information through various popular media sources and documentary programmes and news reporting in newspapers, television and radio. People’s perception about climate change as a phenomenon and its related risks could motivate how to respond to climate-change-induced events. Thus climate change knowledge could influence what to do – what type of measures to take in order to avoid adverse climate change impacts or how to design responses to such impacts when they do occur. Understanding climatic changes and what the ultimate causes are can help in designing sustainable coping and adaptation strategies in Africa, unless people are too fatalistic and believe it is out of their control.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ profound gratitude goes to the South Africa National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Department of Science and Technology (DST) for funding this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Amos Apraku http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6523-5167

Philani Moyo http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9089-7565

Wilson Akpan http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9684-3752

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACPC, 2014. http://www.uneca.org/acpc/ Accessed 14 June 2014.

- Berkes, F & Jolly, D, 2001. Adapting to climate change: social-ecological resilience in a Canadian western Arctic community. Conservation Ecology 5(2), 18. http://www.consecol.org/vol5/iss2/art18/ doi: 10.5751/ES-00342-050218

- Blaikie, P, Cannon, T, Davies, I & Wisner, B, 1994. At risk: Natural hazards , people's vulnerability and disasters. Routledge, London and New York City.

- Bulkeley H & Betsill M, 2003. Cities and climate change, urban sustainability and global environmental governance. Routledge, New York City.

- Burchi, F, 2010. Child nutrition in Mozambique in 2003: The role of mother's schooling and nutrition knowledge. Economics and Human Biology 8(3), 331–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.05.010

- Chu, J, Xia, J, Xu, C & Singh, V, 2010. Statistical downscaling of daily mean temperature, pan evaporation and precipitation for climate change scenarios in Haihe River, China. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 99, 149–161. doi: 10.1007/s00704-009-0129-6

- CSIR, 2011. Climate risk and vulnerability. CSIR, Pretoria.

- Davies, S, 1993. Are coping strategies a cop out? IDS Bulletin 24(4), 60–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.1993.mp24004007.x

- DST, 2011. South African risk and vulnerability atlas. DST CPD print, Pretoria.

- Eriksen, S & Kelly, PM, 2007. Developing credible vulnerability indicators for climate change adaptation policy assessment. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 12, 495–524. doi: 10.1007/s11027-006-3460-6

- Government SA, 2013. South African yearbook 2012/2013. GCIS, Pretoria.

- Hufschmidt, G, 2011. Comparative analysis of several vulnerability concepts. Natural Hazards 58(2), 621–643. doi: 10.1007/s11069-011-9823-7

- Iaquinta, D & Drescher, A, 2000. Defining peri-urban: Understanding rural-urban linkages and their connection to institutional development. United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Rio de Janeiro.

- IPCC, 2001. Assessment report 3 (AR3): An executive summary. IPCC AR3.

- IPCC, 2007. IPCC assessment report 4. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. http://www.ipcc.ch Accessed 28 July 2012.

- IPCC, 2013. Fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- James, H, 2005. Earth's energy imbalance: Confirmation and implications. Science 308, 1431–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1110252

- Johnston, P & Schultze, R, 2010. Report on climate in Eastern Cape. ECDC, East London.

- Kay, A & Davies, H, 2008. Calculating potential evaporation from climate model data: A source of uncertainty for hydrological climate change impacts. Journal of Hydrology 358, 221–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.06.005

- Kelly, PM & Adger, WN, 2000. Climate theory and practice in assessing vulnerability to climate change and facilitating adaptation. Climate Change 47, 325–52. doi: 10.1023/A:1005627828199

- Kepe, T, 2010. ‘Secrets’ that kill: Crisis, custodianship and responsibility in ritual male circumcision in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Social Science and Medicine 70(5), 729–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.016

- Leary, N, Adejuwon, J, Barros, V, Burton, I, Kulkarni, J, Lasco, R, et al., 2009. Climate change and adaptation. Earthscan Publishers, London.

- Lutz, W & Skirbekk, V, 2013. How education drives demography and knowledge informed projections. Interim report no. IR-13-016. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria.

- Moser, C, 1998. Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies: The asset vulnerability framework. World Development 26(1), 1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10015-8

- Moser, C, 2006. Asset-based approaches to poverty reduction in a globalized context: An introduction to asset accumulation policy and summary of workshop findings. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

- Muttarak, R & Lutz, W, 2014. Is education a key to reducing vulnerability to natural disasters and hence unavoidable climate change? Ecology and Society 19(1), 42–9. doi: 10.5751/ES-06476-190142

- Nicholson, S & Kim, J, 1997. The relationship of the El Niño Southern oscillation to African rainfall. International Journal of Climatology 17, 117–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0088(199702)17:2<117::AID-JOC84>3.0.CO;2-O

- Parry, M, Rosenzweig, C, Iglesias, A, Livermore, M, Fischer, G, 2004. Effects of climate change on global food production under SRES emissions and socio-economic scenarios. Global Environmental Change 14, 53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.008

- Pittock, A, 2009. Climate change: The science impacts and solution. CSIRO Publishers, Collingwood.

- Ragab, R & Prudhomme, C, 2002. Climate change and water resources management in arid and semi-arid regions: Prospects and challenges for the 21st century. Biosystems Engineering 8, 3–34. doi: 10.1006/bioe.2001.0013

- Ruddiman, W, 2003. The anthropogenic greenhouse era began thousands of years ago. Climate Change 6, 261–93. doi: 10.1023/B:CLIM.0000004577.17928.fa

- SADC, UNEP, 2010. Southern African sub-regional framework of climate change: Adaptation and mitigation actions, supported by enabling measures of implementation. not indicated. SADC UNEP.

- SAWS, 2010. At the forefront of weather 1860–2010. SAWS, Pretoria.

- SAWS, 2014. http://www.weathersa.co.za/ec

- Shinoda, M, Okatani, T & Saloum, M, 1999. Diurnal variations of rainfall over Niger in the West African Sahel: A comparison between wet and drought years. International Journal of Climatology 19, 81–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0088(199901)19:1<81::AID-JOC350>3.0.CO;2-F

- Statistics South Africa, 2011. 2011 census report. The South African Government, Pretoria.

- Strauss, A & Corbin, J, 1998. Basics of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Voigt, T, Minnen, J, Erhard, M, Viner, D, Koelemeijer, R, Zebisch, M, 2004. Climate change impacts in Europe: Today and in the future; Draft report. Eueopean Union Agency, Copenhagen.

- WMO, 2013. https://www.wmo.int/media/?q=content/wmo-issues-climate-africa-2013

- WMO, 2012. https://www.wmo.int/pages/index_en.html

- Zinyengere, N, Oliver, C & Hachigonta, S, 2013. Crop response to climate change in Southern Africa: A comprehensive review. Planetary and Global Change 111, 118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.08.010