ABSTRACT

Effective management of waste and the promotion and management of recycling activities are necessary for sustainable and liveable cities. A key but unrecognised element in promoting recycling is the efforts of waste pickers who make a living from recycling mainline recyclables. This article aims to describe the approaches used on 10 landfills in South Africa to manage waste pickers’ access to recyclables and their daily activities on the landfills. A multiple case study design and cross-case analysis were used in this study. The sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) was used to analyse and explain the data. The results showed that waste management policies and practices directly influence the waste pickers’ access to recyclable waste and their livelihoods. Finally, some inclusionary and exclusionary practices are highlighted that could guide inclusive, participatory and co-productive practices for waste pickers in South Africa towards increased recognition, access, dignity and income.

1. Introduction

Good waste management is necessary to build sustainable cities. According to the World Bank, it is necessary to improve solid waste management as the pace of waste generation is increasing to the point where it will double by the year 2025 (Hoornweg et al., Citation2013; World Bank, Citation2016). Globally, 1.3 billion tonnes of waste are generated per year, and it is expected that by the year 2025, 2.2 billion tonnes of waste will be generated per year (World Bank, Citation2016). In contrast with the sophisticated waste management practices in developed countries, many developing countries still struggle to dispose of waste generated, mainly due to the burden on municipal budgets and the lack of knowledge and skills of the officials responsible for waste management (Fergutz et al., Citation2011; Guerrero et al., Citation2013).

In South Africa, 54.425 tonnes of waste are generated per day – the 15th highest in the world (World Bank, Citation2016). The Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) states that in South Africa in 2011 only approximately 10% of waste was recycled. The unrecycled balance (98 million tonnes) ended up in landfills (DEA, Citation2012). It is therefore not surprising that South Africa’s landfill areas are rapidly running out of space (Chvatal & Smit, Citation2015). In 1998, the South African Government drew up the National Waste Management Strategy to achieve an integrated waste management solution. The responsibility of managing landfills was given to the local municipalities under the Municipal Systems Act (Act 32, 2000). The focus of the waste management strategy includes the three ‘Rs’, i.e. reduce (waste minimisation), re-use and recycle (Garner, Citation2009; Chvatal & de Smit, Citation2015).

A key, but unrecognised element, in promoting recycling are the efforts by an estimated 60 000 to 90 000 South African waste pickers who make a living from recycling mainline recyclables, either on the streets or on the landfill sites. The waste pickers’ recycling activities are at the lower end of the recycling value chain and yet, over the years, have played a key role in the recycling process (Viljoen, Citation2014; Chvatal & de Smit, Citation2015; Samson, Citation2015). The waste pickers’ activities enabled municipalities to save between R309.2 and R748.8 million on air space in 2014 (Godfrey et al. Citation2016), but the financial importance of their contribution to municipalities has yet to be valued and supported by the recycling sector.

The barriers to entering informal waste picking are considered to be low, however, various other barriers are hindering the waste pickers’ access to, collection and selling of recyclable waste (Viljoen, Citation2014). Inclusionary policies and practices towards waste pickers in the waste management plans of municipalities are becoming critical. The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) (Citation2016) clearly states that no development can be regarded as sustainable if it is not inclusive and participatory and if the affected stakeholders are not able to make decisions on aspects that affect their lives.

This article aims to describe the different waste management practices used on 10 landfills in South Africa to manage waste pickers’ access to recyclables and their daily activities on the landfills. It further assesses the positive and negative externalities that these management practices have on the livelihoods and quality of life of landfill waste pickers.

2. Method

A multiple case study design and cross-case analysis was used in this study. Case study research is a strategy that focuses on understanding the dynamics present within a single setting (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Khan & Van Wynsberghe, Citation2008), and combines data collection methods, such as archives, interviews, questionnaires and observations (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Baxter & Jack, Citation2008). Case study research further aims to answer the questions ‘why’ or ‘how’. Analysing multiple case studies enables the researcher(s) to explore differences and similarities within and between cases, from which new knowledge can emerge. It is important to recognise that case studies do not allow for broad generalisations (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008).

The results described in this article use data and cross-case analyses of 10 landfills in South Africa. Data was collected through questionnaires and qualitative interviews with landfill waste pickers (LWP), municipal waste managers and municipal workers, as well as Buy Back Centre (BBC) representatives and observations. The selected landfills were visited and data were collected from a total of 373 LWP between April 2015 and April 2016. On each landfill, the sample size exceeded 50% of the LWP.

In order to facilitate the cross-case analysis, the sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) was used as illustrated in .

Figure 1. The dimensions of the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF). Source: Adapted from DFID (Citation1999) and Scoones (Citation2009).

Livelihoods can be seen as a means of activities, to make a living (Chambers, Citation1995; Scoones, Citation2009). The SLF offers a unique and comprehensive framework to collect diverse data and provide an integrated analysis of complex and highly dynamic contexts and cases (Scoones, Citation2009). The SLF further focuses on factors and processes that either constrain or enhance impoverished people’s ability to make a living in an economically, ecologically and socially sustainable manner (Krantz, Citation2001).

3. Results

This section starts with a summary of some key characteristics of the 10 landfill sitesFootnote1 and the number of landfill waste pickers on the sites. This is followed by the cross-case analysis of the 10 landfills according to the five dimensions identified in the SLF ().

Table 1. Overview of the sites.

3.1. Dimension 1: vulnerability context

The vulnerability context refers to the external environment in which people exist that affects their livelihoods, such as the broader political and policy settings and socioeconomic conditions. The affected persons have very little control over the external environment (Chambers, Citation1995; DFID, Citation1999; Scoones, Citation2009; Nzeadibe & Mbah, Citation2015).

The activities of LWP must be seen against the background of South Africa’s high unemployment rate (currently 26.7%) (StatsSA, Citation2018) and one of the highest inequality and crime rates in the world (Bhorat, Citation2015). Being unable to find employment, many of these individuals endeavour to eke out a living in an informal urban economy (Neves & Du Toit, Citation2013).

The LWP are operating next to, instead of in conjunction with, the formal waste management system. No clear guidelines or policies exist which could guide local governments on how to incorporate the informal waste pickers into the local government systems (Godfrey et al., Citation2016). Each municipality currently decides how it manages, includes or excludes the waste pickers’ activities. This was evident from the 10 landfills we visited.

On the positive side, the municipality associated with landfill GR built a material recovery facility (MRF) next to the landfill where waste is delivered onto a hard surface. The waste pickers have the opportunity to collect and sort the recyclable waste and separate what they regard as valuable. What is left is then taken to the landfill. The waste is easily accessible and there is a building where the waste pickers can sort and store the recyclable waste and which provides shade, toilets and water to the waste pickers.

At the other extreme are landfills that have no access control, no water or toilets available to the workers; as noted by one of the participants: ‘ … we have to go to the bush’. Due to the lack of supervision on landfills such as OU and PR, gangsters and substance users are present who steal the earnings from, in particular, the women. One of the women shared that the ‘nyaope (a drug) boys always here causing trouble’. Participants confirmed that they are ‘surrounded by a lot of addicts’ and ‘the “skollies” (gangsters) are dangerous’.

One of the greatest risks on the landfill sites was identified as the danger of being run down by the trucks. Participants noted that ‘the trucks can hit you if you're not careful’ and ‘when trucks come in, people rush and push each other’. This is less the case on the MRF on GR landfill as the waste pickers have to wait until waste is dumped on the hard surface before they can access and sort the recyclables.

To prevent waste pickers being hit by trucks and tractors, the landfill managers on PO, VR and BN have appointed ‘pointers’ to separate the trucks dumping the waste from the areas being worked on by the waste pickers. The study by Blaauw et al. (Citation2015) confirmed this practice of using pointers to safeguard waste pickers.

Working on the landfill further poses a number of health risks. Being cut by needles, glass and tins was highlighted by many of the waste pickers, particularly as they are exposed to these objects without wearing gloves or protective clothing. Comments made by the participants were: ‘cutting your fingers or stepping on a nail’ and ‘we get hurt if we don’t have gloves’. In a study by Van Heerden (Citation2015), who bought gloves for the street waste pickers with whom he interacted, found that they preferred to work without gloves as they ‘feel’ their collections when they scratch between the waste. Similar findings were shared by the waste managers who provided gloves and masks to the waste pickers. The researchers also observed that the masks given to the waste pickers on landfill ST were hanging around their necks but were not being used.

More health risks mentioned by the waste pickers are being in contact with rotten food and polluted water, ‘ … . eating rotten food and drinking the wrong things’. This includes being in contact with ‘nappies and aborted babies’, and encountering ‘snakes’. A female waste picker shared how she scarred her face when ‘burning the plastic’ (to get access to the copper). Some shared that they develop chest problems due to the dust, smoke-polluted air, inhaling of chemicals and rotten objects and because of the cold weather in winter. This may lead to the development of illnesses: ‘We get TB easily from the smoke and the chemicals’ and ‘skin rashes’.

Concerns were raised about substance abuse and fighting on the landfills. A few comments from the pickers allude to these risks: ‘The boys can stab you when they are drunk’. One shared that they fight and ‘a friend has been stabbed to death’. Another summed up his life on the landfill as: ‘It’s nice but dangerous. You need to be cautious’.

On the sites such as GR, ST, VR and PO, there are officials on the landfills who implement rules and prevent fighting and substance use on the landfill, while on the OU landfill, there was only one female official responsible for recording the volume of incoming waste, who was not able to, and does not have the mandate to, intervene.

Weather conditions such as rain and extreme cold and heat affect the waste picking activities directly. The heat in summer was mentioned as affecting their functioning on the landfill if they do not have access to shade. A participant mentioned she gets ‘hot and becomes disorientated’. It is only the MRF at landfill GR that provides shelter against these harsh conditions.

In summary, it is quite evident that waste pickers are vulnerable. Some vulnerabilities are inherent to waste picking (such as dirt, pollution and toxic objects) and cannot be changed by management practices, but factors such as protection against cold and heat and criminal behaviour can be managed.

3.2. Dimension 2: livelihood assets

The livelihood assets refer to the assets, resources and capacities of the people within their context. In the SLF, reference is made to the different inter-related assets such as physical, financial, human, natural and social assets (DFID, Citation1999; Scoones, Citation2009; Nzeadibe & Mbah, Citation2015).

3.2.1. Physical assets

The main physical asset is the recyclable waste on the landfill that provides a livelihood for the waste pickers. It is not only the recyclable waste that is of value, but also the access to food, clothes, shoes, jewellery, wood, household objects such as pots, pans, curtains, mattresses and other furniture that it provides. Some 50% of the waste pickers confirmed that they were dependent on the food they accessed on the landfills. On the OU landfill, the waste pickers shared that they refer to the landfill as ‘oumies’ (‘old madam’), who is seen as the provider of all their needs – ‘sy gee vir ons alles’ one participant commented. The waste pickers, as well as other community members (who do not recycle) collect clothes, food, household goods and firewood from the landfill. Electronic and electrical goods, such as kettles, irons, and cell phones, were mentioned as being collected either for their own use, or to be sold or burnt for the valuable metal parts in them. Of importance to the waste pickers was the easy access to the recyclables and goods, which related directly to how the landfill and waste pickers are managed.

Other physical assets for the waste pickers were the basic facilities accessible to them as described in .

Table 2. Basic facilities present at the landfill sites for the waste pickers.

Landfills such as PR, BO, BR and OU had none of the facilities available to the LWP. Having access to shade under which they can sort and store their recyclable waste was valued by the participants at the MRF at the GR landfill. They explained that it allowed them to store their recyclables during the night and they could continue sorting recyclable waste when it rained and when it was very hot or cold. The participants confirmed that access to basic facilities helped to build their dignity.

3.2.2. Human assets

The profiles of the LWP provide some interesting information regarding their age.

Just more than 42% of the LWP in the survey were younger than 35 years of age. The average age of the waste pickers was 39, with the youngest being 18 years old and the oldest aged 71. The importance of the ages of the LWP is that it illustrates that waste picking on landfills is accessible to young and old, if they are physically able to do the work.

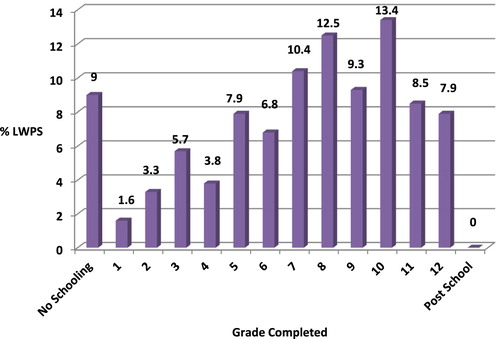

The profiles of the LWP further showed that most participants have very low levels of education, which might explain their inability to access work in the formal economy. shows the highest school educational attainment of the waste pickers in the study.

Figure 2. Highest school qualifications of landfill waste pickers. Source: Research data.

LWPs, landfill waste pickers.

Of the total number of respondents, 9% did not have any schooling, while 43.7% obtained some secondary level education, which ranged from grade 8 to 12. Less than 8% completed matric. From the qualitative question asked as to why they had not completed school, the following themes emerged (see ): Financial difficulties, persistent poverty, family problems and behavioural problems were given as the most prominent reasons for not completing school. These findings are supported by Schenck et al. (Citation2016) and Nzeadibe and Mbah (Citation2015), who also encountered low levels of education amongst the waste pickers and not being able to access formal work.

Table 3. Reasons for not attending school or leaving school before Gr 12.

Waste picking is then one of the few options to earn an income as will be discussed in the next section.

3.2.3. Financial assets

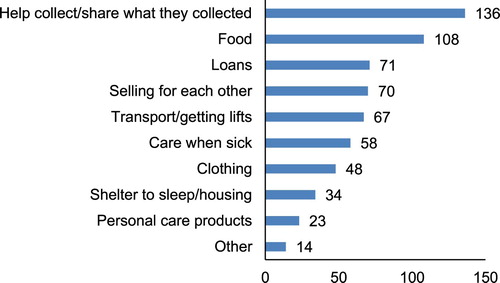

The participants shared that the reason for being on the landfill was to earn a living and waste picking was in many instances ‘the only choice/option’ they had, given the low barriers required. A further significant benefit from collecting recyclables, shared by the waste pickers, was the access to a ‘daily income’ or ‘quick money’. They explained that the income received was not stable and differed daily. Their income depended on factors such as the volume of recyclable waste delivered to the landfill, the accessibility to the recyclable waste, the weather, their health and the fluctuating prices of the recyclable waste. For these reasons, the waste pickers’ actual income in the week before the interview was captured ().

The median income for a good and bad week was R500 (42.34 USD)Footnote2 and R200 (16.93 USD), respectively. There was also a large difference between the mean income for a good week R768.15, (65.04 USD) and a bad week-R288.69 (24.44 USD). The maximum earnings indicated for the previous week was R2000 (169.34 USD). On average the waste picker could earn around R770 (65.20 USD) in a good week. In a bad week, the average earnings would be in the region of R290 (24.55 USD).

For the greater majority of participants, the income they earned by collecting and selling recyclables was their only income. Preventing them to access the recyclable waste would imply the removal of their livelihood.

3.2.4. Social assets

Social assets/capital are defined as the relationships and networks developed by people to survive and improve their livelihoods (DFID, Citation1999; Adama, Citation2012; Neves & Du Toit, Citation2013).

Two sets of important relationships became clear in the study: The one social network was the family network as support, but also as an added responsibility, increasing the waste pickers’ vulnerability. The 331 participants reported a total number of 1 178 dependants who relied on their income ().

Table 4. Total, mean and median number of dependents (n = 331).

The mean number of dependents, who depended on the LWP’s income, excluding the waste picker, was four. The maximum number of dependents was 15 and the median number of dependents was three.

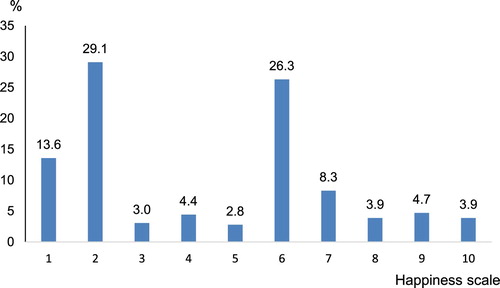

A second social network existed among the waste pickers as explained in .

From previous studies (Viljoen, Citation2014; Van Heerden, Citation2015; Schenck et al., Citation2016), it emerged that the waste pickers were self-employed and worked independently but were supportive of each other. The results of this study confirmed the collaboration between the waste pickers on the landfill sites, with 68% reporting that they supported each other. Much of this support was transactional collaboration such as help collecting and carrying their recyclable waste or selling on behalf of each other, but they made it very clear that they did not work as a collective or shared their earnings.

3.3. Dimension 3: institutional processes and policies

This dimension refers to analysing the organisations, institutions, processes and policies affecting the livelihoods of people (DFID, Citation1999; Scoones, Citation2009). It is these institutions and policies that determine the sustainability of their livelihoods, and how and when the LWP can access, collect and sell the recyclable waste.

Institutions such as the municipality or the private waste management company responsible for managing the landfill, as well as the BBCs, played the most significant role in the lives of the LWP. Without the existence of the BBCs, it would not be possible to collect and sell recyclable waste (Viljoen et al., Citation2012). On visiting the different BBCs, it emerged that there were complex price structures depending on a variety of factors, such as transport costs, quality of recyclable waste and global macro-economic price fluctuations.

The inclusionary and exclusionary practices on the 10 landfills could be summarised in three groups: The uncontrolled, medium controlled and controlled sites as observed by the researchers.

3.3.1. Uncontrolled landfill sites

The management of landfills BO, PR, OU and BR was limited. The only officials on the BO, BR and OU landfills were women who recorded the number of incoming trucks. No-one controlled or restricted access and there was free movement of LWP and other people on the landfills. There were no weighbridges, water, toilets or shade at the landfills.

Discussions with the LWP on the OU landfill revealed gangsters who used substances and robbed, in particular the women, of their earnings.

On the other hand, the uncontrolled landfills provided an advantage to the LWP of freedom of movement and collection. The LWP on these landfills shared that they also collected over weekends to increase their income.

3.3.2. Controlled landfills

Landfills PO and ST outsourced their landfills, while VR was managed by the municipality. These landfills had controlled access. On all three of these landfills there were previously an unmanageable number of LWP present. However, gangsterism and unsafe conditions became hazardous for the LWP and community, and it was therefore decided, with the best of intentions by the municipalities, to fence the landfill and provide controlled access. Only restricted numbers of LWP were permitted. On these landfills, provision was made for water and sanitation. On landfill VR, provision was made for shaded space where the waste pickers could sort and store their recyclable waste, but the facility was far from the dumping area on the landfill and, as a result, was not used by the LWP.

A further restriction implemented by the PO management was that only men were allowed to collect recyclable waste on the landfill ‘to make things less complicated’, according to the landfill manager, and ‘easier to manage’. The positive side of these management approaches was that there was control, order, safety and more dignified working conditions. On the downside, these policies were exclusionary and have had an impact on the income of the LWP. On the ST landfill, for example, at 7:30 in the morning the first 40 pickers at the gate were provided with ‘day-glow’ jackets and given access to the landfill after they had registered with their identity documents. The ‘day-glow’ jackets made them visible and indicated that they had the right to be on the landfill. At 15:00 in the afternoon, all pickers had to leave the landfill so that the waste could be covered. These rules gave the LWPs the opportunity to recover their recyclable waste and, at the same time provided safety measures to prevent being run over by the tractors. The pickers shared that the ST landfill’s ‘first-come first-serve’ policy had resulted in their having to leave home as early as 3:00 am to ensure access to the landfill. Some lived close to the landfill, while others lived an hour’s walk from the landfill. These circumstances created additional vulnerabilities.

In addition, it was shared that a limited volume of recyclable waste could be recovered before 15:00 when the LWP had to leave the landfill as some of the trucks delivering the waste only arrived at the landfill after 11:00. This resulted in a lower income for the LWP and a shortened life span of the landfill. The MRF at the GR landfill was built to get the waste pickers off the landfill site and increase their access to the recyclable waste. All waste is taken to the MRF where the pickers can recover the recyclable waste and other valuables. The MRF is fenced and has strict access control. Access is also on a ‘first come, first serve’ basis and 20 waste pickers need to sign in by producing their identity documents. At 14:00 each day, the front loader clears the surface and the waste not recovered goes to the landfill. After the removal of the waste, pickers can continue sorting the recyclables until the BBC picks them up around 17:00 with their sorted recyclables, but they cannot take out more recyclables. This practice restricts the amount of recyclable waste they can recover ().

Officials, who managed the weighbridge and recorded the volume of waste coming in and going out of the landfill, mentioned that they monitored the activities of the waste pickers to ensure order. The officials indicated that they had the mandate to implement some disciplinary measures, such as banning a waste picker from the site if he or she did not adhere to the ‘rules’ of the MRF.

The MRF in particular provides dignity to the waste pickers, as facilities such as water, toilets and shade are available and waste pickers can collect recyclable waste in all weather conditions. They can store their recyclables at the MRF without the risk of it being stolen. The first-come first-serve method used and the providing of identity documents can be regarded as exclusionary.

3.3.3. Semi-controlled sites

The BN, BS and BO sites could be regarded as semi-/medium controlled sites with staff present who controlled waste entering and exiting the landfill, but who did not manage the waste pickers. Toilets and water were available to waste pickers on the BN and BS landfills, but no shade. Waste pickers created their own shade as shown in .

Figure 6. Landfill waste pickers protecting themselves against the sun at the BN landfill site. Source: Authors.

At none of the 10 landfills could we find active participatory decision-making platforms between the management and the waste pickers. This only took place on the ST landfill, where waste pickers had an elected committee which were consulted on behalf of the waste pickers.

3.4. Dimension 4: livelihood strategies

Livelihood strategies refer to the activities and decisions people make in order to achieve their livelihood goals (DFID, Citation1999; Nzeadibe & Mbah, Citation2015). The reasons for the waste pickers to be on the landfills were explored in the following sections.

3.4.1. Reasons for being on the landfill

The waste pickers were asked what the reasons were for being a waste picker. The following themes appeared from the qualitative data:

Theme 1 spoke of the only opportunity available to earn an income. Comments included: ‘I had no other option’; ‘there was work and money to be made’; ‘I cannot find another job’; and ‘I need to earn to support my family’.

Low skills and lack of qualifications made the waste pickers less fit for formal employment in the current competitive economic climate. Some workers explained that they knew they would never get a formal job as they were ‘too old’, were unemployable as they had ‘never been employed’ or ‘had been in prison’.

Theme 2 refers to the absence of barriers to access waste picking: A participant mentioned that ‘I didn’t have an ID, so I cannot work in the formal sector’. Not having an ID can be a barrier on controlled landfills which require IDs for access to the landfill. Further comments were: ‘ … I cannot work (formally) with TB’; ‘The metro police arrested people who were selling on the streets so I came this side (the landfill) because I didn’t want to go to jail’.

Barriers such as lack of qualifications, poor health and regulations did not prevent the waste pickers from using the opportunity the landfills offered.

In Theme 3, the comments highlighted the fact that being on the landfill and earning a living helped ‘to avoid life of crime’ or ‘to sit and do nothing at home’. To work and have an income was ‘better than being on the road and getting up to mischief’.

Theme 4 provided reasons why the waste pickers came to the landfill and indicated that some used it ‘to have extra income’. Some of the waste pickers who were seasonal workers did waste picking in the off-season to get an ‘income when not (sheep) shearing’.

Theme 5 referred to those who preferred to be waste pickers in order to be independent and to be their ‘own boss’.

3.4.2. Waste picking routine

The waste pickers explained that it was their routine to go to the landfill daily, as this was their workplace or ‘their job’. If they did not recycle daily, there would be no income and food for their families. They arrived at the landfills as early as possible. On the controlled access landfills (ST, PO, VR GR), they could not enter before the gates opened at 7:30 am, while on the landfills with no access control, they could enter and leave at any time and on any day. Some workers slept on the landfills in temporary structures. Most of the pickers left the landfills after the BBCs had picked them and their recyclables up in the afternoon around 17:00 h. On all the landfills in this study, the waste pickers were paid daily ().

3.4.3. Waste picking activities

Not all LWP collect all recyclable waste available on the landfill site. The waste pickers mentioned that they mainly collected those items which the BBCs buy from them. Landfill VR was, for example, the only landfill where waste pickers collected bones, which were supplied to the BBCs for the bone meal milling company close to the town. Waste pickers were selective in the type of recyclables they collected because of the different prices paid for the different recyclables. It was noticed that the pickers on the ST landfill did not collect the cardboard boxes. Due to the limited time they had available to access the waste, they would rather go for the scrap metal and polyethylene terephthalate (PET plastic), which provided the best income. If they could spend more time collecting, they would take the cardboard boxes. An adjustment in the management practice could allow for greater productivity and income for the waste pickers.

Besides the recyclable waste, some waste pickers collected other products for their own or for family use or to sell. These products included bricks, clothes, blankets, cool drink crates, electric appliances, food, computers, heavy loading bags, leather and wood.

From the 365 waste pickers who indicated to whom they sold their waste, the majority (92%) depended on buy-back centres to buy their recyclable waste. Another 8% sold their waste products to private individuals. On the PR and BR landfill sites there were informal buyers who bought from the waste pickers and then sold to the formal BBCs. This added another link in the recycling chain and, according to the waste pickers, negatively affected their income. The waste pickers indicated that their recyclables were being collected by the BBCs and other buyers, as the landfills were too far out of town for the waste pickers to deliver their recyclables. By collecting the recyclable waste from the LWP, the BBCs ensured that the waste was sold to the particular BBC or individual.

3.5. Dimension 5: livelihood outcomes

Livelihood outcomes refer to the achievements or the output of the strategies of the waste pickers (Nzeadibe & Mbah, Citation2015). According to Scoones (Citation2009), livelihood strategies should result in: (1) Creating working days; (2) reducing poverty; (3) enhancing the well-being of the person; (4) developing capacity; and (5) should be able to assist in recovering from setbacks or unexpected problems. The livelihood outcomes will be discussed according to Scoones’ (Citation2009) outcomes.

3.5.1. Outcome 1: creation of working days

Collecting and selling recyclable waste on the landfills create regular working days for the waste pickers in order to ensure a daily income. It depends on the waste pickers how many days per week they want to work and it depends on the management of the landfill whether they allow the waste pickers on the landfills over weekends. Some of the waste pickers indicated that they worked seven days a week. Working on the landfill allowed for some flexibility, as mothers said that they were able to attend to their families in the morning and see their children off to school, after which they could come to the landfill. The men usually started earlier and left later. Some of the waste pickers also mentioned that this allowed them to have a choice when and how often they want to work.

3.5.2. Outcome 2: poverty reduction

The informal economy is mainly seen as a subsistence strategy (Nzeadibe & Mbah, Citation2015; Radchenko, Citation2017). The current income of the waste pickers assists them to sustain themselves and their families, as supported by Turner at al. (Citation2014). It is argued that factors such as good governance, maximum access to recyclables and dignified protective working conditions can assist in increasing their income and possible movement out of poverty.

3.5.3. Outcome 3: enhance the subjective well-being (SWB) of the landfill waste pickers

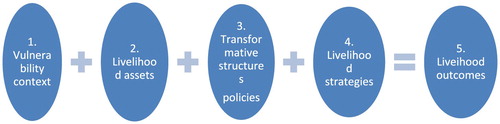

Scoones (Citation2009) argues that a livelihood should enhance well-being. One of the questions asked of the waste pickers was to determine how happy they were (on a scale of 1 to 10 with 10 being very happy and 1 being not happy) with their life on the landfill, given the working conditions described in the study. shows the results of the subjective experiences shared by the waste pickers.

The self-reported happiness of the waste pickers mirrors the harsh reality of their lives. Half (52,9%) of the respondents indicated subjective well-being values of 5 and less. The mean score was 6.2 for the whole research population, with the median being 5.

Well-being, according to Hicky & Du Toit (Citation2007), is linked to many factors, such as working conditions, sense of agency, social relations and income. These aspects were confirmed by the waste pickers.

The waste pickers’ unhappiness included the following themes:

Lack of safety:

‘Unhappy about violence among other waste pickers’ and ‘Corruption – there are nyaope smokers. We don’t work peacefully’.

Lack of support:

‘Nobody really cares about us and don’t help us’.

‘I have no choice. The place is not conducive for people’.

‘I get paid daily’.

‘I am self-employed, work when I want’,

‘Nobody tells me what to do’.

‘Being able to assist my mother with her income’, and ‘Just happy I can provide for my kids and send money home’.

Experience of social support:

‘I like it here. I have many friends’, and ‘We help each other out a lot’.

3.5.4. Outcome 4: develop capabilities

One of the major factors in poverty reduction is the growth of people’s capabilities (Scoones, Citation2009; Rodrik, Citation2015; Radchenko, Citation2017). This was also confirmed by the waste pickers. The waste pickers shared that the skills needed to recycle were learned ‘on the job’. They learned from each other and from the BBCs what was of value and how recyclables should be salvaged and sorted. They gained knowledge regarding the prices paid for the recyclables, the fluctuation in the prices and, in particular they learned which BBCs were willing to pay the best prices for various items.

3.5.5. Outcome 5: recover from setbacks

A livelihood is sustainable when it is able to recover from setbacks. (DFID, Citation1999; Turner et al., Citation2014; Rodrik, Citation2015). The volume of waste generated is on the increase and waste recycling is becoming more critical and necessary. The biggest threat to the livelihoods of the waste pickers is linked to waste management of municipalities in general, including the management of the landfills, the threat of closing the landfills, technology and the possibility of policies and practices that could make waste pickers obsolete. This study showed that careful consideration should be given to decisions made regarding the waste pickers. Not all waste pickers, for instance, would be able to pick waste on the kerbsides (if that is an option) due to limited physical health, strength and safety. The studies by Schenck et al. (Citation2016) and Viljoen (Citation2014) also showed that women were less able to operate as street waste pickers. This study showed that MRFs could be considered as more viable and dignified options.

4. Discussion and conclusion

This article attempted to provide an overview of the management of 10 landfills in South Africa and the effect that the various ways of non/governance has on the livelihoods of the waste pickers. Using the SLF as an analysis framework, the article describes complexities, strengths and vulnerabilities in the livelihood of the waste pickers and how this could be improved if well managed by the municipalities. The SLF further emphasised the complex interplay of the relationships between the role players involved in the landfills. The analysis further highlighted the following lessons learnt from the 10 case studies:

All actions or non-actions by municipalities have consequences on the livelihoods and dignity of the LWP. Uncontrolled landfills may provide sufficient waste, food and household necessities, but the working conditions are harsh and undignified and, in addition, in many cases there are no provision for shade, toilets and access to water. A ‘free for all’ landfill site results in fierce competition, gangsterism and increased risks for the waste pickers and the community members.

Controlled landfills and MRFs, on the other hand, minimise the risks, ensure more dignified working conditions and make the landfill more accessible to the public. However, the critical, unintended consequences emerging from the case studies are that a landfill, where access and numbers are formally controlled, results in the exclusion of some waste pickers, as well as time constraints limiting access to recyclable waste and income. The limited time for recyclable waste recovery causes shorter lifespan of the landfills. Waste diversion from the landfills can increase with well researched and planned management.

This study also supports Fergutz et al. (Citation2011), Guerrero et al. (Citation2013), Chen and Ijjasz-Vasques (Citation2016) and Lindell’s (Citation2010) findings that municipalities should commit to clear guidelines, sufficient budgets and well-trained municipal staff which should enhance the:

Recognition of the value and service waste pickers add to the recycling chain;

Ease of access to the waste;

Negotiations for fair prices for the waste they collect;

Creation of safe spaces for working and storing; and

The creation of systems, processes and structures through which the waste pickers can participate in the decision-making processes which may impact their livelihoods and well-being.

To facilitate inclusion and participation requires respect for the LWP, respect for human rights and democratic governance (Lindell, Citation2010; Dugarova, Citation2015; Radchenko, Citation2017). Fergutz et al. (Citation2011) therefore propose policies and practices that facilitate inclusive ‘co-production’ between local government, business and the informal waste pickers. This research has shown that waste management policies and practices directly influence the waste pickers’ access to recyclable waste and their livelihoods (Blaauw et al., Citation2015; Chvatal & Smit, Citation2015; Nzeadibe & Mbah, Citation2015; Godfrey et al., Citation2016).

4.1. Recommendations

Many recommendations can be made on how landfills and the waste pickers working on them can be managed and controlled, but no ‘one fits all’ approach is possible. It is therefore recommended that integrated and participatory processes be respectfully facilitated between each municipality, landfill management, BBCs and waste pickers to work out the best policies and practices to enhance increased recycling opportunities, enhance the dignity of the workers and to benefit all role players. It would, in particular, be beneficial to facilitate participatory processes to be able to plan and implement recycling and the diversion of waste from the landfills with the knowledge and expertise from also those at the lower end or coalface of the recycling value chain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Catherina J Schenck http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5299-5335

Phillip F Blaauw http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8750-4946

Elizabeth C Swart http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7786-3117

Jacoba M M Viljoen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6087-9684

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Abbreviations were used to indicate the landfill sites for anonymity.

References

- Adama, O, 2012. Urban livelihoods and social networks: Emerging relations in informal recycling in Kaduna Nigeria. Urban Forum 23(4), 449–66. doi: 10.1007/s12132-012-9159-8

- Baxter, P & Jack, S, 2008. Qualitative case study methodology study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 13(4), 544–59.

- Bhorat, H, 2015. Is South Africa the most unequal society in the world? Conversation 30 September 2015.

- Blaauw, PF, Viljoen, JMM, Schenck, CJ, & Swart, EC, 2015. To “spot” and “point”: Managing waste pickers’ access to landfill waste in the North-West Province. Africagrowth Agenda 12(2), 18–21.

- Chambers, R, 1995. Poverty and livelihoods: Whose reality counts? Discussion paper 347. Institute for Development Studies IDS, Brighton UK.

- Chen, M & Ijjasz-Vasques, E, 2016. A virtuous circle: Integrating waste pickers into solid waste management. The World Bank. Voices: Perspectives on development. https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/virtuous-circle-integrating-waste-pickers-solid-waste-management Accessed 14 May 2017.

- Chvatal, JA & de Smit, AV, 2015. Waste management policy: Implications for landfill waste salvagers in the Western Cape. International Journal of Environment and Waste Management 16(1), 1–29. doi: 10.1504/IJEWM.2015.070480

- Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), 2012. National waste information baseline report. Department of Environmental Affairs, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Department of International Development (DFID), 1999. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets, DFID, London.

- Dugarova, E, 2015. Social inclusion, poverty eradication and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United National Research Institute for Social Development, (UNRISD), Geneva.

- Eisenhardt, KM, 1989. Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Research 14(4), 532–50. doi: 10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- Fergutz, O, Dias, S, & Mitlin, D, 2011. Developing urban waste management in Brazil with waste picker organisations. Environment and Urbanisation 23(2), 597–608. doi: 10.1177/0956247811418742

- Garner, E, 2009. An assessment of waste management practices in South Africa: A case study of Marian Hill landfill site, eThekwini Municipality. Unpublished Master’s dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal Durban.

- Godfrey, L, Strydom, W, & Phukubye, R, 2016. Integrating the informal sector into the South African waste and recycling economy in the context of extended producer responsibility. Council for Science and Industrial Research (CSIR) Briefing note series. Pretoria.

- Guerrero, LA, Maas, G, & Hogland, W, 2013. Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste Management 33(1), 220–32. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2012.09.008

- Hicky, S, & Du Toit, A, 2007. Adverse incorporation, social exclusion and chronic poverty. Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC), Working Paper 81, Bergen, Norway.

- Hoornweg, D, Bhada-Tata, P, & Kennedy, C, 2013. Environment: Waste production must peak this century. Nature. www.nature.com/news/environment-waste-production-must-peak-this-century-1.14032. 13 October 2013 Accessed 19 May 2016.

- Khan, S, & Van Wynsberghe, R, 2008. Cultivating the under mined: Cross case analysis as knowledge mobilisation. Qualitative Social Research 9(1). Art 34.

- Krantz, L, 2001. The sustainable livelihood approach to poverty reduction: An introduction. Swedish International Cooperation Development Agency (SIDA), Stockholm.

- Lindell, I, 2010. Introduction: The changing politics of informality – collective organizing, alliances and scales of engagement. In Lindell, I (Ed.), Africa’s informal workers: Collective agency, alliances and transnational organising in urban Africa (pp. 1–32). Zed Books, London.

- Neves, D, & Du Toit, A, 2013. Rural livelihoods in South Africa: Complexity, vulnerability and differentiation. Journal of Agrarian Change 13(1), 93–115. doi: 10.1111/joac.12009

- Nzeadibe, TC, & Mbah, PO, 2015. Beyond urban vulnerability: Interrogating the social sustainability of a livelihood in the in the informal economy of Nigerian cities. Review of African Political Economy 42(144), 279–98. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2014.997692

- Radchenko, N, 2017. Informal employment in developing economies: Multiple heterogeneity. Journal of Development Studies 53(4), 495–513. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2016.1199854

- Rodrik, D, 2015. The past, present and future of economic growth. In Allen, F (Ed.), Toward a better global economy (pp. 1–63). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Samson, M, 2015. Accumulation by dispossession and the informal economy-struggles over knowledge, being and waste at a Soweto garbage dump. Society and Space 33(5), 813–30.

- Schenck, CJ, Blaauw, PF, & Viljoen, JMM, 2016. The socio economic differences between landfill and street waste pickers in the free state province, South Africa. Development Southern Africa 33(4), 532–47. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2016.1179099

- Scoones, I, 2009. Livelihoods perspectives in rural development. Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1), 171–96. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820503

- Statistics South Africa (StatsSA), 2018. Work and labour force. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id = 737&id = 1. Accessed 23 March 2018.

- Turner, S, Cilliers, J, & Hughes, B, 2014. Reducing poverty in Africa: Realistic targets for the post 2015 MDG’S and Agenda 2063. Africa Futures Paper 10, Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, South Africa.

- United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), 2016. Policy innovations for transformative change: Implementing the 2030 agenda for social development. UNRISD, Geneva.

- Van Heerden, A, 2015. Valuing waste and wasting value: Rethinking planning with informality by learning from skarrellers in Cape Town’s southern suburbs. Unpublished Master’s dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Viljoen, JMM, 2014. Economic and social aspects of street waste pickers in South Africa. (Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of Economics & Econometrics, University of Johannesburg). https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za Accessed 6 July 2016.

- Viljoen, JMM, Schenck, CJ, & Blaauw, PF, 2012. The role and linkages of buy back centres in the recycling industry: Pretoria and Bloemfontein, South Africa. Acta Commercii 12(1): 1–12 doi: 10.4102/ac.v12i1.125

- World Bank, 2016. Waste not, want not – solid waste at the heart of sustainable development. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/03/03/waste-not-want-not---solid-waste-at-the-heart-of-sustainable-development Accessed 13 May 2017.