ABSTRACT

This paper evaluates the progress made by Zambia on the third Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of increasing the political participation of women in urban areas. Based on Nancy Fraser's framework of redistribution-recognition-participatory parity we demonstrate that women's political participation in Zambia is thwarted by a range of historical, economic, socio-cultural and political factors along with specific factors in urban areas such as long work hours, the informal economy and lack of familial support. It concludes that without the introduction of gender-specific quotas within local bodies in Zambia, the newly instituted Sustainable Development Goals will see growing difficulty in achieving progress.

1. Introduction

Zambia's Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2014, at 0.586, places the country in the mid-level category in the area of human development. Zambia ranks 139th out of 188 countries and territories. With regards to gender equality indicators, Zambia's Gender Inequality Index (GII) is 0.587, and its Gender Development Index (GDI) is 0.917, both also ranking Zambia 139th out of 188 countries in their respective categories; its Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) is 0.426 (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], Citation2015). Zambia amended its Constitution in 2016, reaffirming and recognising equal rights for women and men, aligning statutory law with various international laws further undermining customary law. Zambia has seen some improvements in women's representation. For the first time since its independence in 1964, Zambia elected in 2015 a female vice president, Inonge Wina, and a female chief justice, Irene Chirwa Mambilima. As of 2016, the proportion of seats held by women in the Zambian Parliament had marginally increased to 18 per cent from 11 per cent in 2014 (The World Bank, Citation2016) (see Table A1). Following the most recent tripartite elections in 2016, seven women have been appointed as cabinet ministers (Lusaka Times, Citation2016a). However, the general scenario appears to be one of women’s dismissal considering Zambia’s failure to match up with the achievements of its Southern African Development Community (SADC) counterparts.

Despite signing the SADC Gender Protocol, with the 2015 deadline of ensuring 50 per cent women’s representation across all levels of politics, Zambia's progress in achieving gender equity and equality has moved at a slow pace (Lowe Morna et al., Citation2015). Observations based on the 2016 tripartite elections indicate the worsening situation of women candidates due to exorbitant nomination fees (Jimmy Carter Centre, Citation2016). In addition, the most recent figures on women's participation indicate a further decline from 7 per cent in 2009 to 6 per cent in 2015, 44 per cent short of the SADC goal of 50 per cent women's representation in local government (Lowe Morna et al., Citation2015). In fact, Zambia is one of the few countries that have seen a decline in the numbers of women in local government in 2015. Moreover, the country did not introduce quotas for the 2016 elections. In comparison to this, three other countries in the SADC (Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa) have come to achieve the 50 per cent gender representation target (see Table A2). Originally aligned to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development is a unique sub-regional instrument. It harmonises goals for African and global development with 28 specific targets clustered into groups such as constitutional and legal rights; governance (representation and participation); education and training; productive resources and employment, economic empowerment; gender-based violence; health; HIV/AIDS; peace building and conflict resolution; media, information and communication; and implementation of 50/50 parity by 2015. Similarly, Zambia has signed and ratified the African Charter on Human and People's Rights (Maputo Protocol) of the African Union (AU), which stipulates that state parties enforce affirmative action to ensure gender parity in the political process (African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, Citation2003). Zambia's failure to make progress similar to its African counterparts such as Egypt, Rwanda, South Africa and Uganda is attributed to the lack of special measures such as legally mandated quotas or seats for women in Parliament (UNDP, Citation2013).

Historically, Articles 2 and 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948 recognised equal political rights irrespective of sex (United Nations, Citation1948) and in 1966, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) reiterated the same principles (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Citation1966). The Convention on the Political Rights of Women was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) (United Nations, Citation1953) in 1953 and was a precursor to the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which the UNGA adopted in 1979. CEDAW moved the right of political participation another step towards de facto equality by affirming the obligation of State Parties to take affirmative action to accelerate the participation of women in politics and their representation in other public decision-making positions. Currently, almost all African countries have ratified CEDAW, except for Sudan and Somalia (Klugman & Twigg, Citation2015). Before the adoption of the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development, the SADC Council of Ministers endorsed the SADC Gender Policy (2007) and the SADC Heads of State and Government also signed the Declaration on Gender and Development in September 1997. Article 12 of the SADC (Citation2008) stipulates that ‘States Parties shall endeavour that, by 2015, at least fifty percent of decision-making positions in the public and private sectors are held by women including the use of affirmative action measures’ (Southern African Development Community, Citation2012).

The last century was marked by rapid shifts and movements towards urban centres from rural areas. Urban centres are at the centre of economic growth and opportunities, presumably leading to improved living standards, education and health facilities. There is a common assumption that as women become urbanised they have greater access to resources and greater autonomy over their lives (The World Bank, Citation2012). For women, urbanisation has meant moving away from stagnant rural agrarian economies and traditional barriers presented by patriarchal social mores and a patriarchal cultural ethos towards greater employment possibilities, lower fertility levels and social mobility. Global cities are centres of devalorisation of the economy marked by feminisation of the labour force for women specifically from developing countries or ethnic minority communities (Sassen, Citation1997). Traditional restrictions on women's mobility along with reproductive responsibilities reinforce home-based informal economic activities (Chant & Mcilwaine, Citation2013). The assumptions underpinning modernisation and development that urbanisation will lead to women's emancipation remain an unfulfilled promise, as urban areas are marked by increasing inequalities, poor housing and sanitation conditions, and increasing productive and reproductive burdens on women with the emergence of female-headed households and nuclear families with near-absent formal child care facilities. The exclusion of women in the political arena emerges from what Sylvia Chant refers to as the ‘urban penalty’ (Citation2007:25). Greater democratisation and decentralisation of power have resulted in women's increasing concentration at lower echelons of governmental organisations without any possibility of recognition or leadership roles (Chant & Mcilwaine, Citation2013).

In 2015, an estimated 41 per cent of Zambia's population lived in urban areas, largely concentrated in eight major towns in the Copperbelt Province (The World Bank, Citation2002, Citation2016). The 1991 Local Government Act empowered 22 city and municipal authorities, which aimed to address the dysfunctional administrative structures that had resulted from the centralisation of authority. Resources did not back these progressive moves, and as a result, minimal or no qualitative improvements were noted in urban governance. Women's representation remains a serious concern, as witnessed by the latest available data from SADC indicating that in 2014, at local levels, women continue to have poor representation in decision-making. Out of 1422 councillors in Zambia, only 82 (6 per cent) were women, although the number of female chief executives has increased from 3 in 2012 to 17 in the 103 councils most recently (Gender Links For Equality and Justice, Citation2015).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) signed on 25–27 September 2015 mark the global consensus on how to achieve gender equality. Specifically, Goal 11 relates to making cities safe, inclusive and resilient and Goal 5 includes 34 indicators on gender equality (The United Nations, Citation2015). The SDGs build on the achievements of the MDGs, specifically the third goal recognised political participation of women as an important stepping-stone for the overall emancipation of women (though it does not specifically address urban governance). Since committing to the MDGs, this study highlights that Zambia has seen marginal improvements in the number of seats held by women in political office at all levels of governance (Tables A1 and A2). This is an indication of the country's failure to implement and encourage women's political participation. Based on the case study of Zambia, this article critically evaluates the reasons for the poor participation of urban women in politics, especially in light of the SDGs’ and MDGs’ impetus on gender equality. First, based on Nancy Fraser's three-layered conceptual framework of redistribution, recognition and participatory parity we argue that international policy approaches emphasise redistribution strategies without giving adequate consideration to recognition and representation. Second, the paper evaluates the reasons for Zambia's limited progress on political participation of women in urban areas. Third, it concludes with reflections on re-strategising with greater impetus on recognition, representation and participatory parity for the realisation of the SDGs related to greater political participation of women.

2. Women's political participation in Zambia: tripartite arrangement of redistribution-recognition-representation

Originally, the redistribution-recognition dilemma proposed by Fraser (Citation1995) placed the question of inequality within the binary opposition of cultural and economic injustice. This twofold classification is based on Jürgen Habermas's propositions that political institutions belong to the economy, which produces inequality, whereas in John Rawls’ terms, they are part of ‘the basic structure’ of society. The redistribution standpoint views injustice as emanating from economic structures of a society, whereas the recognition standpoint views inequality as having its basis in culture. Therefore, approaches to address injustices also vary as approaches based on redistribution focus on economic injustice whereas recognition focuses on representation, interpretation and communication. Nancy Fraser postulates that the goals of such social policies are deeply limited if they prioritise economic injustice over a cultural basis for such injustice. Cultural struggles for recognition of the Dalits of India, Blacks of South Africa and the United States of America, and the Aboriginals of Australia pre-date any questions of material inequality. In fact, material inequality is the result of cultural devaluation of these groups as naturally inferior to the dominant groups of whites, Brahmins or men. Based on this dual opposition, Fraser regards questions of sex and gender, gender clearly having its basis in cultural-valuation, as does race in the United States. From the purely redistributive lens, gender justice requires explicit recognition of women's unremunerated productive and reproductive work, which in essence is the basis for the continued discrimination against women in society. However, politics of recognition require a nuanced understanding in terms of class, race and gender. Intersectionality is an important dimension of feminist analysis, as women are not only disadvantaged because of their gender but also because of their race, caste, religion, aboriginal and ethnic status (Crenshaw, Citation1991). Seen through the prism of recognition, urban penalties are an additional caveat to existing inequalities suffered by women owing to their inferior status. Urbanisation further ruptures the protracted division of labour in poor countries. Women are allocated the additional burdens of paid work along with unpaid familial responsibilities (Brouder & Sweetman, Citation2015). Subsequently, Nancy Fraser added ‘participatory parity’ to ensure the equal participation of all adult members of society as peers; not only addressed based on legal equality but also in terms of shared material resources and intersubjective meaning associated with human equality as intrinsic to institutions (Fraser, Citation1996, Citation2005). She advocates the establishment of alliances with progressive forces who believe in gender-just social policy and with forces who believe in politics of recognition. From the Fraserian lens, gender mainstreaming in the political arena falls into the category of redistribution to bring about greater economic efficiency without considering structural barriers women face in seeking recognition and representation.

As evident from the early origins of gender mainstreaming strategies traced back to Esther Boserup's work first published as Women's Role in Economic Development in 1970, which set the stage for the United Nations Decade for Women (1976–85) (Boserup, Citation2013), policymakers made decisions based on colonial biases that underlie the non-recognition of women's contribution to agriculture and industry. Gender mainstreaming originated in the context of the 1985 Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi and the UN Decade for Women, which marked the conceptual shift from the women in development approach to the gender and development approach by making visible women's poor social status and undervalued role in the economy (Moser, Citation1993). The women in development approach of the 1970s placed undue emphasis on investing in women to improve development outcomes (Razavi & Miller, Citation1995) whereas the gender and development approach focused on gender as a social and cultural category and encapsulated the prevailing power relations in society as a serious impediment to realising women's capabilities (Kabeer, Citation1994). The impetus for women's political participation came from the World Bank in its 2001 report titled Engendering Development through Gender Equality in Rights, Resources, and Voice, which endorsed the view that greater rights and public participation of women lead to better business and productive economies (The World Bank, Citation2001). Two studies were influential in shaping the World Bank's gender approach to corruption and political governance: Dollar et al. (Citation1999) and Swamy et al. (Citation2001), which seem to indicate a negative relationship between women's representation in political governance and corruption in parliaments. Such overarching conclusions have come into question. For example, Sung (Citation2003) contends that corruption cannot be a hindrance to women's participation, as liberal democracy is a prerequisite to both gender equality and government accountability.

3. Zambia's urban governance: mainstreaming gender in politics

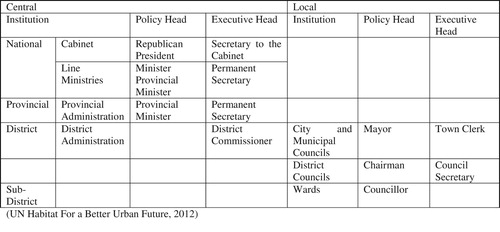

Zambia comprises the nine provinces of Copperbelt, Central, Northern, Southern, Eastern, Western, Lusaka, Northwestern and Luapula, each headed by a Provincial Minister or Deputy Minister appointed by the President. There are 72 local authorities or councils in each of these provinces. The Department of Local Government Administration facilitates the coordination of the nine provincial offices (Commonwealth Network Zambia, Citation2016). At the end of the one-party political system in the 1990s, the Government of Zambia launched its attempts at local governance. The Local Administration Act of 1980 was made redundant in December 1991; a new Act came into force, called the Local Government Act (Cities and Local Government, Citation2015). The national decentralisation policy in 2002 was brought forth to enhance governance by giving citizens more authority and power in decision-making at the local level (European Commission, Citation2012). However, progress has been slow due to the continued dependence of local governments on the central government administration and their reliance on the support of civil society organisations (The Hunger Project, Citation2013). Local governments are called councils, and as of October 2012 there were 89 councils – 4 city councils, 15 municipal councils and 70 district councils – with a total of 1422 wards (Commonwealth Local Government Forum, Citation2016). City councils are located in those urban districts which have more population and diversification in terms of economic activities; while the municipal councils cover the suburban regions (see ).

Figure 1. Multi-level government in urban Zambia. Source: UN Habitat For a Better Urban Future (2012).

In terms of gender representation, local governance is specifically important, as it is more accessible for women to participate in decision-making and become leaders. Additional barriers have been created with the implementation of conditionalities such as the need of municipal councillors to have a proven certificate of 12 years’ schooling and the heavy registration fees to be paid to the Zambian Electoral Council equivalent to 100–200 euros. The absence of party-based quotas to ensure the presence of women in all levels of party governance does indeed thwart women's political participation (Momba, Citation2005). Currently, there are discussions within the Zambian government to introduce legislated quotas and affirmative action for women in politics (Lusaka Times, Citation2016b).

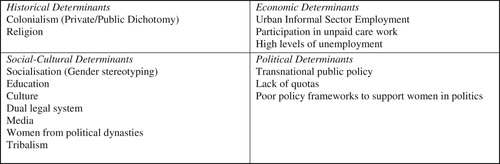

As Fraser (Citation1995) has argued, gender justice struggles must be embedded in a tripartite framework of redistribution, recognition and participatory parity. Based on this conceptual framework, we clearly locate gender-based exclusion of women in urban governance in Zambia as entrenched in historical colonial antecedents and structural realities of transnational public policy, dual legal systems, economic privation, social and cultural conceptions of feminine behaviour, media stereotypes and political exigencies (depicted in ). This study largely draws on secondary sources of information to draw out the multiple and intersecting reasons why women still remain at the margins of Zambia's urban politics.

3.1. Historical continuities and discontinuities

Existing evidence suggests that historically there was little urban development in the Zambian copper belts, except for the copper mining, smelting and trading in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (Siegel, Citation1988). Early urbanisation is linked to the British South Africa Company's control of mines in the copper belts of then Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). Zambia was one of the world's largest copper producers under colonial rule, with the development of railways in 1903 further facilitating trade. By the 1929–1939 the region had a mining boom, which lasted until the Great Depression. It brought more Europeans and a larger African labour force to the area, making the twin settlements of Nkana-Kitwe easily the largest town in Northern Rhodesia with 80 000 inhabitants, including nearly 10 000 Europeans (Steel, Citation1957). Officially, Northern Rhodesia became a British colony in 1924, as initially it had been subject to the British South Africa Company since the 1890s. The capitalist modes of production and colonial influence altered the autonomy, authority and power of women as colonial economic and mining policies strictly reinforced gender-specific roles (Geisler, Citation2006). The residents of Copperbelt were from the matrilineal Bantu ethnic groups, especially those of Northern and Central Zambia (Evans, Citation2015), as well as the Bemba ethnic group (Taylor, Citation2006). The matrilineal nature of their kinships implied that women enjoyed a relatively higher status; specifically their status improved with age and childbirth (see Evans, Citation2015).

The early origins of discriminatory gender practices are traced to the nexus between colonial government and the mining industry. The initial reluctance of colonialists to hire married labourers gave way to the recruitment of married men, as they found that married labourers were more efficient and stable because they had wives to take care of them; they were well fed and looked after and were more likely to be responsible to their families (Parpart, Citation1986a, Citation1986b). Under the colonial administration, gender hierarchy was strictly ensured by restrictions on women's economic activities so that no disruption resulted in the supply of stable and cheap male labour to the companies (Chauncey, Citation1981). In 1930, legislation was passed prohibiting women from working, and only small numbers had jobs as nurses, welfare workers and teachers. Mostly, women engaged in informal work such as beer brewing, gardening and providing domestic and sexual services, which reflects their ingenuity in carving out a niche for themselves. The British South Africa Company, which ruled Zambia from 1898 to 1924, set up Native Commissioner Courts where company officials adjudicated all kinds of disputes between African men and women, particularly marriage, divorce and abduction cases. These courts enforced Bantu customary laws which previously were not codified but were legitimised by the colonial rule. These newly codified laws reinterpreted custom in ways that enhanced traditional male authority with practices such as restrictions on women moving to urban areas (Parpart, Citation1994).

The Zambian independence movement provided some openings for women's branches of nationalist parties such as the United National Independence Party (UNIP), which organised rural and urban protests. The UNIP Women's Brigade participated in literacy drives to aid voter registration, and helped organise town funerals, mass demonstrations, rallies and boycotts (Parpart, Citation1986a; Geisler, Citation2004). The Women's Brigade in the UNIP was limited to supporting men's political activities, and the Christian ideals of the ideal mother and wife were strongly reinforced (Geisler, Citation2004:24). The downturn in the copper process in the mid-1970s resulted in a decline in the Zambian economy which resulted in job losses, wage cuts, inflation, consumer shortages and riots over the subsequent decade (Ferguson, Citation1999; Larmer & Fraser, Citation2007). These economic changes did not alter any existing gender division of labour, as Evans (Citation2012) notes that a change in women's employment patterns occurred only in the 1990s.

3.2. Post-independence era politics

Since it declared independence, Zambia has had three political parties under six different ruling governments: the first under the leadership of Kenneth Kaunda of UNIP in a one-party state (1964–91); Fredrick Chiluba (1991–2002) of the Movement for Multi-party Democracy (MMD); Levi Manawasa who died in office (2002–8) of the MMD; Rupiah Banda (2008–11, United National Independence Party (UNIP)); Michael Sata who died in office (2011–4) of the Patriotic Front (PF); and the current president Edgar Chagwa Lungu of the PF (Sardanis, Citation2014). The Women's Brigade, which was later renamed the ‘Women's League’, was established by Kenneth Kaunda as an appurtenance of the UNIP with no leadership structure or decision making for women. The male members were the authorities, setting the agenda for their meetings, discussion points and the venue for these meetings. Following the 1991 elections and the end of one-party rule, a new generation of younger educated women began to contest traditional notions of subservience imposed on women. These groups were seen as the cause of moral and economic decay and endangering national identity and so they received a backlash from not only men but also older women in the Women's League who were in defence of traditionalism. The Women's League was comprised of older-generation urban women with low formal education. Most were small-scale marketers in the urban informal sector that relied on the protection of their party membership and excluded professional women from participating (Geisler, Citation2006). With the change of government in 1991, the new government at the time assured women of an end to marginalisation of women in politics and the previously excluded professional women were encouraged to participate. To achieve this, the National Women's Lobby Group (NWLG) was formed in 1991, a non-partisan group, comprised of lawyers, gender activists and so on, that would advance the cause of women in politics. The NWLG, however, received criticism from the ousted UNIP of sidelining women from the party, whereas in the new government under the MMD, the chairperson of the party's Women's Development Committee did not support the NWLG (Geisler, Citation2006).

Although women were not given priority in either of the UNIP and MMD governments, many hoped that a new government would not only put an end to corruption but also enforce affirmative action when it came to the advancement of women especially in political affairs. The newly elected PF, which won the elections on 23 September 2011, condoned MMD gender policy and also admitted the failures of their predecessors to harmonise international protocols like the CEDAW signed by the MMD in 1985 (Raicheva-Stover & Ibroscheva, Citation2014). Subsequently, President Michael Sata appointed the country's first ever woman inspector general as well as other women to prominent positions, such as: the Chiefs of the Anti-Corruption Commission and the Drug Enforcement Commission; Chief Justice; and Deputy Chief Justice. Only 10.5 per cent of Cabinet Ministers were women and they were appointed to portfolios such as local government, housing, early education, minister of chiefs and environmental protection and traditional affairs (see Raicheva-Stover & Ibroscheva, Citation2014:66). President Michael Sata said during an interview that he did not support the advancement of legal provisions such as quotas in reserving seats for women and believed that women should compete equally with men and not obtain seats served on a silver platter (Lusaka Times, Citation2013).

3.3. Dual legal systems of Zambia

One of the complexities when it comes to domestication of international treaties for African states is that of a dualistic approach. The Zambian constitution reinforces the legal validity of statutory law over customary law. Zambia's new constitution proclaims that it is the supreme law of Zambia, and if any other law is inconsistent with the constitution that other law shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void (Article 1, Clause 3). Similarly, international laws such as CEDAW stress legal obligations on the part of the member states which have ratified the treaty. However, CEDAW has stressed legal reforms without addressing the questions of culture and religion, which sanction women's subordination. The SADC Protocol on Gender and Development was signed and adopted by the Heads of State and Government, with the exception of Botswana (which signed it in 2017) and Mauritius. The importance of the SADC protocol emanates from the shared cultural heritage of the African nations; a deeper understanding of the environment in which they are applied that provides a sense of African solidarity; and finally the SADC protocol was signed much later in 2008, unlike CEDAW, which has had a greater time available for member states to ratify and implement it. The statutory law has precedence in legal terms in all post-colonial states. However, the challenge of harmonisation remains with persisting tensions between written statutory laws which uphold universal values versus local customary laws that are often antagonistic to gender equality.

3.4. Economic factors

Recent estimates suggest that there is near gender parity in employment rates in Zambia, with 57.1 per cent of males and 58.7 per cent of females employed in rural areas and 42.9 per cent of males and 41.3 per cent of females employed in urban areas. However, an area of concern is that a total of 83.9 per cent of the population is employed in the informal sector and 16.1 per cent in the formal sector. In rural areas, 92.2 per cent of the population is employed in the informal sector and 7.8 per cent in formal employment whereas in urban areas 72.4 per cent is employed in the informal sector and 27.6 per cent is employed in the formal sector. However, analysis by sex shows that the unemployment rate for males decreased from 8.1 per cent in 2008 to 6.3 per cent in 2012. It however increased to 8.4 per cent in 2014. The unemployment rate for females increased from 7.7 per cent in 2008 to 9.2 per cent in 2012, and later decreased to 6.5 per cent in 2014 (Central Statistical Office, Citation2016). In Zambia, 80.3 per cent of women in comparison to 62.9 per cent of men work in the informal sector in urban areas (ILO, Citation2013). The informal economy as such is a contested concept in sub-Saharan Africa, originally conceptualised by the British anthropologist Keith Hart, based on Clifford Geertz’s binary analysis of the firm economy versus the bazar or pasar. Hart undertook fieldwork amongst Frafra migrants in Ghana based on which he characterised the informal economy as marginal living, inefficiency and financial transactions based on trust. Thus the precarious situation of women in Zambia in the informal sector highlights that a majority of women undertake activities that are ‘survivalist’ and labour-intensive in nature and which do have ramifications on their political participation and agency.

3.5. Education

Education empowers women to participate in various political activities. It provides them with the confidence to articulate and communicate their views and participate in activities of charitable organisations and religious establishments, which are arenas for networking for political activities (Burns et al., Citation2001). Historically, Zambian women suffered a disadvantage in education as colonial and missionary education placed a premium on male education and labour market participation, whereas females’ education was seen as a hindrance to their ability to manage their marital households (Evans, Citation2016). There is a common assumption that urbanisation improves education and life options for young women and improves community participation amongst women (Birch & Wachter, Citation2011). Zambian education since the implementation of the MDGs has seen progress, especially at the primary level, with more girls proceeding to higher levels of education. Even though the provinces with the greatest strides in female education reveal that urban areas experienced the highest increase in the number of educated girls, there have been cases of female dropouts in urban areas; however, the dropout rates in rural areas are higher than those in urban areas (World Health Organisation, Citation2016). Albeit these improvements will take time to connect to women's political participation as the exclusion of women from politics is reinforced as they lack education and finances, which places them behind their male counterparts (Osei-Hwedie, Citation1998).

3.6. Political dynasties and tribalism

Ethnic and tribal identities still matter in Zambian politics, as reflected by the continued victory of certain parties in specific provinces (Posner, Citation2005). These political and social wedges are not ‘gender neutral’, as women leaders inherit their power from familial connections. Osei-Hwedie (Citation1998) illustrates that in the 1996 general elections, of the 16 women MPs, eight women were Bemba speakers, followed by five (31 per cent) Lozi speakers, two (13 per cent) Nyanja speakers and one (6 per cent) Tonga speaker. These women are embedded in patronage politics, clearly demonstrated by the lack of gender agendas in their or their party's political campaigns (Ferguson, Citation1999). Although women benefit from their respective political dynasties, men still maintain real control of the political parties’ agendas for the most part (Hoogensen & Solheim, Citation2006). Political reform and economic crisis in Africa have weakened the capacity of patronage networks to mobilise political support; they have led, not necessarily to a repudiation of patronage politics by African women, but rather to greater space, at least for some women, within the hidden public (Beck, Citation2003:152).

3.7. Political factors

A range of factors have contributed to the improvements to women's participation in politics such as aid, post-conflict treaties and constitutions including gender equality clauses and the establishment of parties with female heads, including Dr Inonge Mbikusita-Lewanika, who started the National Party in Zambia in 1991 (Ndlovu & Mutale, Citation2013). Female elites also act as pressure groups to adapt international laws on quotas, win female votes and combat Islamic influence on equality norms (Tripp, Citation2015). Tripp & Kang (Citation2008) conclude, based on their empirical analysis, that reserved seats and voluntary party quotas play a vital role in improving women's representation in national parliaments. Six presidents, including the incumbent president, have governed Zambia. This means that each ruling party has come with its own agenda and policies and has at times weakened different strategies put in place with respect to education, health, gender issues etc.

3.8. Media

Two aspects of the media are critical for women politicians: the amount and the nature of coverage (Campus, Citation2013:39). In the most recent election, 2016, The Media Institute of South Africa noted that media had a tendency to ignore women, with 81 per cent of media space reserved for men, leaving only 19 per cent of the space for women. Of this 19 per cent, only 5 per cent of coverage was about women candidates (Zambia Elections Information Centre, Citation2016). Twange (Citation2014) carried out a study from September 2011 to September 2012 on 18 women members of parliament (MPs) in the widely circulated Post and Zambia Daily Mail, private and government-owned newspapers respectively, to see how much coverage female MPs were given and what topics were present in the press coverage. The two papers had covered 126 stories in total, with the Post covering 69 per cent and the Daily Mail covering 31 per cent; a third of the women received no coverage apart from demographic characteristics such as marital status, age, education etc. in the Post. For the most part, women politicians received coverage for their stances on stereotypically female issues such as health and education.

4. Concluding remarks

Gender mainstreaming is a toolbox, which provides a comprehensive approach to substantive equality for women across the world. Feminists have pointed to the variations in the normative and technical understanding of gender mainstreaming owing to economic, social and cultural realities of individual countries (Booth & Bennett, Citation2002) and the excessive focus on techniques promoted by the AU, European Union (EU), SADC and UNDP leaves little scope for transformatory feminist politics (Hafner-Burton & Pollack, Citation2002; Daly, Citation2005). In light of global advancements in women's political participation, it is indeed noteworthy to recall, as Dahlerup & Freidenvall (Citation2005) do, that the incremental track followed by Scandinavian countries took almost 100 years, whereas African countries are on a fast track in terms of women's representation. Therefore, recent gender mainstreaming initiatives do have intrinsic importance and cannot be merely sidelined as technical measures. As Nancy Fraser poses the question, ‘how can we integrate claims for redistribution, recognition and representation so as to challenge the full range of gender injustices in a globalising world?’ (Fraser, Citation2005:306). Fraser's threefold approach to gender justice is indeed a valuable instrument in recognising that redistribution or achieving economic efficiency on the basis of quotas is only one aspect of emancipation, which should be embedded in wider questions of recognition and representation.

Zambia's limited success in achieving the MDGs and the SADC targets is a result of multifarious factors juxtaposed against pre-colonial notions of gender differences; colonial imperialist policies which actively dissuaded women's paid work; and post-colonial realities of lopsided urban development along with various cultural stereotypes represented in the media and the persistence of political dynasties and tribal norms. More importantly, quotas should be visualised as more than an economic redistribution strategy emanating from transnational agencies and should be embedded in the questions of reconciling historical disadvantages along with the existing structural realities of women's privation and exclusion due to non-recognition of precarious unpaid work along with the cultural and political glass ceiling. For the achievement of the SDGs requires many progressive steps such as quotas along with a range of training programmes to improve women's political skills. On the surface, the legislative and policy improvements do translate to the presence of more women in traditional male bastions of politics. These improvements are a stepping-stone for addressing more nuanced and subjective dimensions of political empowerment and its importance to society.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the O.P. Jindal Global University for supporting this study. All errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. KN wrote this article with the support of a Research Excellence Fellowship, Central European University, Budapest, the Open Society Foundation and O.P. Jindal Global University, India.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Keerty Nakray http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3835-2218

References

- African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, 2003. Protocol to the African charter on human and people’s rights on the rights of women in Africa. [Online]. http://www.achpr.org/instruments/women-protocol/ [Accessed 1 December 2016].

- Beck, L, 2003. Democratization and the hidden public: The impact of patronage networks on Senegalese women. Comparative Politics 35, 147–169. doi: 10.2307/4150149

- Birch, L & Wachter, M, 2011. Global urbanization. University of Pennsylvania Press, Pennsylvania.

- Booth, C & Bennett, C, 2002. Gender mainstreaming in the European Union: Towards a new conception and practice of equal opportunities. European Journal of Women’s Studies 9, 430–66. doi: 10.1177/13505068020090040401

- Boserup, E, 2013. Woman’s role in economic development. Routledge, London.

- Brouder, A, & Sweetman, C, 2015. Introduction: Working on gender equality in urban areas. Gender and Development 23, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2015.1026642

- Burns, N, Schlozman, L & Verba, S, 2001. The private roots of public action: Gender, equality and political participation. Harvard University Press, Massachussets.

- Campus, D, 2013. Women political leaders and the media. Palgrave MacMillan, London.

- Central Statistical Office, 2016. Selected socio-economic indicators report 2015. [Online] http://www.zamstats.gov.zm/phocadownload/Dissemination/2015%20Selected%20Socio-economic%20Indicators%20Final.pdf [Accessed 16 March 2018].

- Chant, S, 2007. Gender, cities and the millennium development goals in the global south. Gender Institute, LSE. http://www.lse.ac.uk/genderInstitute/pdf/CHANT%20GIWP.pdf

- Chant, S & Mcilwaine, C, 2013. Gender, urban development and the politics of space. 4 June. http://www.e-ir.info/2013/06/04/gender-urban-development-and-the-politics-of-space/ Accessed 25 December 2016.

- Chauncey, G, 1981. The locus of reproduction: Women’s labour in the Zambian Copperbelt, 1927–1953. Journal of Southern African Studies 7, 135–164. doi: 10.1080/03057078108708024

- Cities and Local Government, 2015. UCLG country profiles Republic of Zambia. UCLG, Lusaka.

- Commonwealth Local Government Forum, 2016. Commonwealth local government forum. [Online]. http://www.clgf.org.uk/ [Accessed 1 January 2016].

- Commonwealth Network Zambia, 2016. Provinces in Zambia. [Online]. http://www.commonwealthofnations.org/info/regions-in-zambia/ [Accessed 12 December 2016].

- Crenshaw, K, 1991. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43, 1241–99. doi: 10.2307/1229039

- Dahlerup, D & Freidenvall, L, 2005. Quotas as a ‘fast track’ to equal representation for women. International Feminist Journal of Politics 7, 26–48. doi: 10.1080/1461674042000324673

- Daly, M, 2005. Gender mainstreaming in theory and practice. Social Politics 12, 433–450. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxi023

- Dollar, D, Fisman, R & Gatti, R, 1999. Are women really the ‘fairer’ sex? Corruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization (The World Bank Development Research Group) 46(4), 423–29. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00169-X

- European Commission, 2012. Civil society: Improving service delivery and local governance in Zambia. EuropeAid, Lusaka.

- Evans, A, 2012. World development report 2012: Radical redistribution or just tinkering within the template? Development 55, 134–37. doi: 10.1057/dev.2011.115

- Evans, A, 2015. History lessons for gender equality from the Zambian Copperbelt, 1900–1990. Gender, Place and Culture 22, 344–62. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2013.855706

- Evans, A, 2016. For the elections, we want women!’: Closing the gender gap in Zambian politics. Development and Change 47, 388–411. doi: 10.1111/dech.12224

- Ferguson, J, 1999. Expectations of modernity: Myths and meanings of urban life on the Zambian Copperbelt. University of California, Berkeley.

- Fraser, N, 1995. From redistribution to recognition? Dilemmas of justice in a “Post-Socialist” age. New Left Review 212, 68–93.

- Fraser, N, 1996. Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition and participation. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, 1–60. Stanford University, California.

- Fraser, N, 2005. Mapping the feminist imagination: From redistribution to recognition to representation. Constellations: An International Journal of Critical and Democratic Theory 12(3), 295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1351-0487.2005.00418.x

- Geisler, G, 2004. Women and the remaking of politics in Southern Africa. NORDISKA AFRIKAINSTITUTET, Uppsala.

- Geisler, G, 2006. ‘A second liberation’: Lobbying for women’s political representation in Zambia, Botswana and Namibia. Journal of Southern African Studies 32, 69–84. doi: 10.1080/03057070500493787

- Gender Links for Equality and Justice, 2015. Zambia: Zambia still committed to women empowerment. [Online]. http://genderlinks.org.za/news/zambia-still-committed-to-women-empowerment-2015-06-04/ [Accessed 19 December 2016].

- Hafner-Burton, E, & Pollack, M, 2002. Gender mainstreaming and global governance. Feminist Legal Studies 10, 285–98. doi: 10.1023/A:1021232031081

- Hoogensen, G, & Solheim, O, 2006. Women in power: World leaders since 1960. Praeger, Westport, CT.

- International Labour Organization, 2013. Statistical update on employment in the informal economy. ILO Department of Statistics. http://laborsta.ilo.org/applv8/data/INFORMAL_ECONOMY/2012-06-Statistical%20update%20-%20v2.pdf.

- Jimmy Carter Centre, 2016. Election observation mission Zambia, general elections and referendum 2016. Carter Centre, Atlanta.

- Kabeer, N, 1994. Reversed realities: Gender hierarchies in development thought. Verso, London.

- Klugman, J, & Twigg, S, 2015. Gender at work in Africa: Legal constraints and opportunities for reform. Oxford Human Rights Hub, Oxford. http://wappp.hks.harvard.edu/files/wappp/files/oxhrh-working-paper-no-3-klugman.pdf.

- Larmer, M & Fraser, A, 2007. Of cabbages and King Cobra: Populist politics and Zambia's 2006 election. African Affairs 106(425), 611–37. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adm058

- Lowe-Morna, C, Dube, S, & Makamure, L, 2015. SADC gender protocol 2015 barometer. Annual. Gender Links, Johannesburg.

- Lusaka Times, 2013. President Sata rejects quota system that favours women. https://www.lusakatimes.com/2012/03/08/president-sata-rejects-quota-system-favours-women/ [Accessed 31/1/2016].

- Lusaka Times, 2016a. Women’s Lobby hails President Lungu for appointing women to cabinet. [Online]. https://www.lusakatimes.com/2016/09/29/womens-lobby-hails-president-lungu-appointing-women-cabinet/ [Accessed 2 December 2016].

- Lusaka Times, 2016b. Legislation to ensure quotas for women in politics underway. [Online]. https://www.lusakatimes.com/2016/11/17/legislation-ensure-quotas-women-politics-underway/ [Accessed 21 December 2016].

- Momba, J, 2005. Women and youth participation. Eisa Research Report 17. Political Parties and the Quest for Democratic Consolidation in Zambia, Lusaka.

- Moser, C, 1993. Gender planning and development theory, practice and training. Routledge, New York and London.

- Ndlovu, S & Mutale, S, 2013. Emerging trends in women’s participation in politics in Africa. American International Journal of Contemporary Research 3(11), 72–79.

- Osei-Hwedie, B, 1998. Women’s role in post-independence Zambia politics. Atlantis 22(2), 85–96.

- Parpart, J, 1986a. The household and the mine shaft: Gender and class struggles on the Zambian Copperbelt. Journal of Southern African Studies 13, 36–56. doi: 10.1080/03057078608708131

- Parpart, J, 1986b. Women and the state in Africa. Working Paper 117 Halifax, Canada 1–50.

- Parpart, J, 1994. ‘Where is your mother?’: Gender, urban marriage, and colonial discourse on the Zambian Copperbelt, 1924–1945. The International Journal of African Historical Studies 27, 241–71. doi: 10.2307/221025

- Posner, D, 2005. Institutions and ethnic politics in Africa. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Raicheva-Stover, M & Ibroscheva, E, 2014. Women in politics and media: Prespectives from nations in transition. Bloomsbury Academic, New York and London.

- Razavi, S & Miller, C, 1995. From WID to GAD: Conceptual shifts in the women and development discourse. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Geneva.

- SADC, 2008. SADC framework for achieving gender parity in political and decision making positions by 2015. https://www.sadc.int/files/3813/5435/8903/FINAL-_SADC_Framework_for_Achieving_Gender_Parity_in_Political_and_Decision_Making_Positions_by_2015.pdf

- Sardanis, A, 2014. Zambia: The first 50 years. I.B. Tauris and Company Limited, New York.

- Sassen, S, 1997. Informalization in advanced market economies. International Labor Organization, Geneva.

- Siegel, B, 1988. Bomas, missions and mines: The making of centers on the Zambian Copperbelts. African Studies Review 31(3), 61–84. doi: 10.2307/524073

- Southern African Development Community, 2012. Women in politics and decision-making. SADC, Gaborone.

- Steel, RW, 1957. The Copperbelt of Northern Rhodesia. Geography 42(2), 83–92.

- Sung, H, 2003. Fairer sex or fairer system? Gender and corruption revisited. Social Forces 82, 703–23. doi: 10.1353/sof.2004.0028

- Swamy, A, Knack, S, Lee, Y & Azfar, O, 2001. Gender and corruption. Journal of Development Economics 64(1), 25–55. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00123-1

- Taylor, SD, 2006. Culture and customs of Zambia. Greenwood Press, London.

- The Hunger Project, 2013. Participatory local democracy gender focused, community led development for all. [Online]. https://localdemocracy.net/countries/africa-southern/zambia/ [Accessed 1 December 2013].

- The United Nations, 2015. Sustainable development goals 17 goals to transform our world. [Online]. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ [Accessed 1 January 2016].

- The World Bank, 2001. Engendering development through gender equality in rights, resources and voice. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- The World Bank, 2002. Upgrading of low income settlements country assessment report. The World Bank. http://web.mit.edu/urbanupgrading/upgrading/case-examples/overview-africa/country-assessments/reports/Zambia-report.html.

- The World Bank, 2012. Towards gender equality in East Asia and the Pacific: A comparison to the world development report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- The World Bank, 2016. Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments. [Online]. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS?locations=ZM [Accessed 10 November 2016].

- Tripp, M, 2015. Women and power in post-conflict Africa. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Tripp, M & Kang, A, 2008. The global impact of quotas: On the fast track to increased female legislative representation. Political Science. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1041&context=poliscifacpub.

- Twange K, 2014. Zambian women MPs: An examination of coverage by the post and Zambia Daily Mail. In Women in politics and media: Perspectives from nations in transition, by Maria Raicheva-Stover & Elza Ibroscheva, 65–81. Bloomsbury Academic, Norfolk.

- UNDP, 2013. Millennium development goals 2013. UNDP, Lusaka.

- United Nations, 1948. Universal declaration of human rights. [Online]. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ [Accessed 26 December 2016].

- United Nations, 1953. Convention on the political rights of women New York. [Online]. http://www.un.org.ua/images/Convention_on_the_Political_Rights_of_Women_eng1.pdf [Accessed 26 December 2016].

- United Nations Development Programme, 2015. Human development report 2015, UNDP, New York.

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 1966. International covenant on civil and political rights. [Online]. http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx [Accessed 26 December 2016].

- World Health Organization, 2016. MDG Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education. [Online]. http://www.aho.afro.who.int/profiles_information/index.php/Zambia:MDG_Goal_2:_Achieve_universal_primary_education [Accessed 1 January 2017].

- Zambia Elections Information Centre, 2016. Zambia elections 2016 - ZEIC launches citizens pre-election report. [Online]. http://allafrica.com/stories/201608110992.html [Accessed 1 January 2017].