ABSTRACT

Municipalities are well positioned to support adaptation of vulnerable people to climate change; however, they seldom integrate climate change into their planning for social development. The building of adaptive capacity for sustainable adaptation requires that municipalities understand and mainstream climate change into their plans, and develop context-specific adaptation strategies that address existing social development issues. A desktop analysis was conducted to compare the planning landscape in six District Municipalities in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, focusing on Municipal Integrated Development Plans (IDPs). A scoring system was developed for comparing the IDPs of the municipalities, based on levels of context-specific information about climate change, mainstreaming of climate change with other development concerns, and vertical integration across district and local municipalities, amongst other themes. Overall, the mainstreaming of climate change in municipal IDPs in the Eastern Cape remains weak, and requires critical attention if sustainable adaptation is to be achieved.

1. Introduction

Climate change cannot be viewed in isolation from social development issues. While all regions of the world are affected by climate change, it is the poorest regions and poorest people who will bear the brunt of the impacts (Reid et al., Citation2009; Harris, Citation2010; Roberts, Citation2013; Spires & Shackleton, Citation2018). The rural poor are particularly vulnerable, as they are heavily dependent on the sectors most directly affected by climate change, such as agriculture, ecosystems and water (DEA, Citation2016). Subnational actors, such as municipalities, are arguably best suited to implement climate change adaptation plans and practices (Roberts, Citation2008; Measham et al., Citation2011; Picketts et al., Citation2014). This is because municipalities have direct interface with communities and their needs. Furthermore, local municipal officials in partnership with communities can ideally develop context-specific adaptation strategies that address the main impacts of climate change in their locality, and should provide tangible benefits directly to the affected local communities (Measham et al., Citation2011; Picketts et al., Citation2014). However, climate change policy and planning documents at the level of municipal governance rarely recognise the key underlying structural drivers of vulnerability, or consider the influence of other stressors poor communities are faced with (Picketts et al., Citation2014). At the same time, municipalities often struggle to integrate climate change perspectives into existing social development planning and functions (Aylett, Citation2014). This is of particular concern in South Africa which remains plagued by the past injustices caused by Apartheid, high levels of poverty and inequality, gender-based violence, and health concerns such as HIV/Aids (NDP, Citation2011). These challenges are intensified in the Eastern Cape, due to it being South Africa’s poorest, and fourth most highly populated province (StatsSA Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Thus, adaptive responses that reduce vulnerability to current, as well as future, climate change are particularly crucial in the Eastern Cape (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014).

Municipal Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) are the core municipal documents in South Africa which provide context-specific solutions to key challenges, in order to achieve long-term sustainable development. However, a critical weakness is that municipal IDPs often have reactive, sector-based, technical approaches to climate change adaptation (Roberts, Citation2008). This reduces the potential to produce more pro-active, long-term climate change adaptation strategies (Measham et al., Citation2011), or to better integrate climate change adaptation into social development policy (Glaas et al., Citation2010). In this context, climate change is seen as competing with, rather than in synergy with, other priorities such as health, nutrition, housing, sanitation and economic growth (Aylett, Citation2014). Other challenges facing local government when it comes to planned adaptation include a lack of coordination between government departments and tiers of government; challenges with ‘up-scaling’ and fundraising for adaptation projects that cannot be measured for success in the present, especially within the target-driven discourse of municipalities; and lastly institutional resistance to change (Spires et al., Citation2014). South African municipalities are characterised by high levels of dysfunction and corruption, and struggle to respond to the pressing service delivery needs within their mandates (Monkam, Citation2014), even without the added pressure of responding to climate change. Within this challenging context, researchers and policy-makers must seek innovative ways to integrate climate change adaptation within municipal plans (Picketts et al., Citation2014; DEA, Citation2016). To do this, it is necessary to understand what municipalities have been doing (or not) with respect to planning for climate change, whether such planning mainstreams climate vulnerability and adaptation options across sectors, and where the gaps and obstacles are.

Given the focus on planning, this research, as a first step, aimed to analyse and compare the IDPs of six district municipalities (DMs) in the Eastern Cape in terms of whether they support sustainable adaptation to climate change. The IDPs of the local municipalities (LMs) falling within the analysed DMs were also reviewed to establish if vertical linkages exist between the DMs and LMs.

The concepts of mainstreaming and sustainable adaptation provided useful lenses through which to do this, as both recognise the links between development and adaptation. Mainstreaming involves incorporating climate change adaptation across all spheres of policies and strategies which aim to alleviate vulnerability, in order to create an enabling policy environment for adaptation to climate change (Kok & De Coninck, Citation2007). Sustainable adaptation recognises issues of social justice, i.e. the structural deficits that shape vulnerability, and the impacts of multiple stressors on poor people, as well the need for environmental integrity (Eriksen et al., Citation2011; Eriksen & Brown, Citation2011). Eriksen et al. (Citation2011:7) argue that ‘fundamental societal transformations are required’ to achieve sustainable adaptation. This highlights the importance of considering climate change actions in relation to social development concerns, especially in vulnerable regions such as the Eastern Cape.

Complementary to this, Lemos et al. (Citation2013) introduce the idea of generic and specific adaptive capacity, and envision these as essential components in formulating climate change adaptation responses that are sustainable in the long term. Generic adaptive capacity is defined as the assets and entitlements that build the ability to cope with a range of stressors, and often involves addressing long-standing social development and inequality issues such as the lack of income, health, power and voice, access to land and resources, and education (Lemos et al., Citation2013). Specific adaptive capacity refers to the conditions that prepare people to cope and recover from specific climatic threats and is essentially about improving risk management (Eakin et al., Citation2014).

Building adaptive capacity to decrease vulnerability entails designing and implementing policies and plans that address both generic and specific adaptive capacity. Given this framing, the assumption behind this research is that, if IDPs reflect a nuanced, well integrated, socially just and mainstreamed understanding of climate change, then this will create an enabling environment for the improvement of the generic and specific adaptive capacity of vulnerable people and build their capacity to cope with and adapt to climate change.

2. Background and context

2.1. Climate change in South Africa

The current evidence of climate change in South Africa has been well established across the literature (IPCC, Citation2014). The Eastern Cape is projected to have higher temperatures, higher frequency of extreme rainfall, and drier conditions particularly in summer and autumn (DEA, Citation2013; LTAS, Citation2013). These projections are crucial in formulating plans which enable particularly vulnerable regions in South Africa to adapt to future climate change impacts.

2.2. Eastern Cape risk and vulnerability context

The Eastern Cape is arguably the province that is most vulnerable to climate change in South Africa (Le Roux & Van Huyssteen, Citation2013). This region has an area of 168 966 km2 and is the fourth most highly populated province in the country, with a population of 6.5 million people (StatsSA, Citation2017b). Factors such as poverty, inequality and climatic variability are equally important in determining the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of an area (Le Roux & Van Huyssteen, Citation2013). The Eastern Cape is the poorest province in South Africa, with 12.7% of households defined as ‘multidimensionally poor’ (StatsSA, Citation2017a), suggesting low generic adaptive capacity to climate change. Furthermore, the Eastern Cape’s highly variable climate makes it difficult to project future climate change in this region (Engelbrecht & Landman, Citation2013). These high levels of uncertainty undermine the opportunity to build-specific adaptive capacity. Consequently, as a result of the Eastern Cape’s high vulnerability status in an uncertain climate, it is critical for local government in this province to plan for adaptation that is mainstreamed and that focuses on vulnerability and the fostering of both generic and specific adaptive capacity.

2.3. Relevant policy and planning landscape

Adaptation to an uncertain climate is crucial in achieving national social development objectives (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014). Section 24 of the Constitution, which is the supreme law of the land, explicitly provides the link between environmental and socio-economic concerns. This link is reinforced in the National Development Plan, which states that climate change is a developmental issue. Furthermore, the National Climate Change Response White Paper (NCCRWP, Citation2011) states the commitments imposed on the country by international conventions such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In terms of the UNFCCC, South Africa has legally binding obligations to mainstream climate change into social, economic and environmental policy (Article 4f). International and national climate change goals and priorities have been successfully incorporated into the Eastern Cape Climate Change Response Strategy (ECCCRS, Citation2011). The ECCCRS identifies that climate change adaptation responses are cross-sectoral in nature. For example, the ECCCRS states that ‘integrated response programmes are required where multiple sectors and departments contribute to a common climate change issue’.

District municipalities tend to represent more marginalised rural areas, have higher levels of unemployment and poverty amongst residents, and less financial and human resources within the municipality, than metropolitan municipalities. Section 83(3) (a) of the Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998, (the Act), provides that a DM must ‘seek to achieve the integrated, sustainable and equitable social and economic development of its area as a whole by ensuring integrated development planning for the district as a whole.’ In order to realise national development goals, the district municipal IDPs set out the priorities, existing conditions, challenges, projects and resources available for the development of the district. Additionally, section 84(1) (a) of the Act specifies that district municipalities should provide a framework IDP for the local municipalities within the district. This suggests that what is incorporated at DM level should be filtered down to LM level.

In terms of planning and implementation, if the international mandate of mainstreaming climate change into development and the drafting of detailed climate change adaptation response strategies are to be achieved at a municipal level, they need to be incorporated across all municipal IDPs. If climate change adaptation strategies are not mentioned in the IDP, there will be no budget afforded to such a strategy. Therefore, planning is a crucial stage in adaptation responses, and needs to be done comprehensively for the effective implementation of climate change adaptation strategies.

3. Methods

As our primary interest for this piece of research is the municipal planning process and evidence of engagement with climate change risk, vulnerability and sustainable adaptation, a desk top review and structured analysis of key planning documents (IDPs) was undertaken. This provided insights into how climate change is dealt with in each municipality and what is being considered or not relative to international best practice. Further research, which could include interviews and focus groups with officials, would be needed to understand why the IDPs look like they do (why there are gaps, minimal integration with poverty and development concerns, limited mention of adaptation strategies, etc.).

3.1. Policies and plans reviewed

The documents that were considered for this paper are provided in .

International, national and provincial legislation and policy, pertaining to climate change and social development, were essential to consider as they provide the overarching principles which inform the objectives of municipal IDPs and guide future actions . Furthermore, they were useful when drafting the key thematic areas used in the analysis of the IDPs.

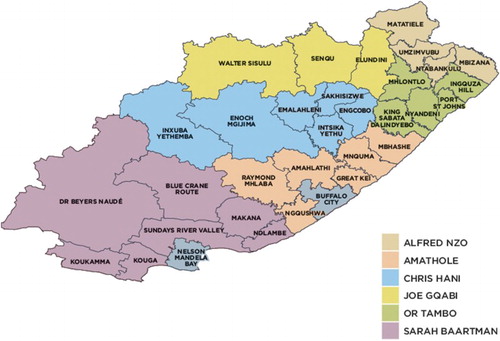

In terms of municipalities, the Eastern Cape consists of: two metropolitan municipalities, Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality and Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality; and six DMs, Sarah Baartman (previously named Cacadu), Joe Gqabi, Amathole, Chris Hani, OR Tambo and Alfred Nzo (). The six DMs are further divided into 37 LMs ().

Figure 2. Map of the district and metropolitan municipalities in the Eastern Cape. Source: Collins & Main, 2013.

Figure 3. Map of the local municipalities in the Eastern Cape. Source: www.municipalities.co.za.

District municipal IDPs are formulated for a period of five years. This is known as the ‘final IDP’. The final IDP is reviewed every year. These yearly revisions are known as ‘IDP reviews’. This study attempted to analyse the IDP reviews as far as possible, because they cover recent responses and solutions to key challenges in the district. The final 2012–2017 IDPs are a five-year plan, describing the district vision of where it will be by 2017. At a DM and LM level, the latest available IDP review at the time that this study was carried out (2014/2015 IDP) was downloaded from the relevant municipal websites. Similarly, the earlier 2011/2012 IDP reviews for each district municipality were downloaded to allow assessment of progress over time. At a DM level, the final IDPs reviews (2016/17) for the five-year plans were scanned for evidence of budgeting for climate change-related activities.

Unfortunately, not all of the municipal websites were updated on a regular basis. This proved problematic in trying to download IDP reviews from specific years for all municipalities. Furthermore, not all strategies and programmes mentioned in certain IDPs were available for public viewing. This meant that it was not possible to compare IDPs reviews from the same year for all municipalities; however all were within the five year planning frame.

3.2. Document analysis

With regard to document analysis, international, national and provincial policies and plans were reviewed in terms of their aims and objectives, particularly with regard to mainstreaming climate change across departments and levels of government and the incorporation of a detailed climate change adaptation strategy.

A method of policy analysis devised by Stokey & Zeckhauser (Citation1978) was used to examine the DM IDPs. According to this method of analysis, one must bear the context of the policy or strategy in mind when interpreting it. Second, one must have constant regard for the underlying Constitutional principles which govern the policy or strategy. Third, the goals of the policy or strategy must be identified. For this study, nine major core themes were developed, using the framing concepts of sustainable adaptation and adaptive capacity as defined above, to draw a conclusion as to whether the district municipal IDP reflected mainstreaming and supported sustainable adaptation to climate change or not (). These nine core themes related to : (1) whether climate change is mentioned in the IDP’s social development sectors; (2) the incorporation of adequate and context-specific information on climate change; (3) evidence of alignment with the UNFCCC and the NCCRWP; (4) types of interventions mentioned in response to climate change; (5) the main developmental concerns in the IDP; (6) whether there is integration of climate change in the IDP’s disaster risk management section; (7) the priority afforded to climate change in the IDP; (8) whether vulnerability and poverty are mentioned in relation to climate change; and (9) whether there have there been improvements over time in terms of mainstreaming climate change in the IDP.

Table 1. Key for the ranking system of the nine core themes.

In order to determine which DMs provided the most conducive environment for sustainable adaptation to climate change, relative to the other DMs in the study, each core theme was rated on a scale from zero to three () with a highest possible score of 27. Once each core theme was scored, the total for each DM was tallied and the scores compared.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Is climate change integrated with social development concerns?

Climate change was not mentioned in any of the sections dealing with the social development concerns of poverty, gender and health in any of the DM IDPs (, row 1). Climate change is only incorporated in environmental sections. This suggests that the ECCCRS’ goal of including multi-sectoral planning for climate change at all levels in the Eastern Cape is not being realised. This situating of climate change solely within the environmental sector is not uncommon and has been mentioned by other authors working at local government level in South Africa (e.g. Pasquini et al., Citation2015; Spires & Shackleton, Citation2018). Such a limiting perspective is seen as a major barrier to advancing adaptation that supports the most vulnerable residents of a country (Conway & Mustelin, Citation2014; Shackleton et al., Citation2015; Spires & Shackleton, Citation2018).

Table 2. Comparison of the six district municipal IDPs in relation to the nine core themes.

4.2. Is there adequate and context-specific information on climate change?

South Africa arguably has the most advanced research, observation and climate modelling programme in Africa (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014). Municipalities need to take advantage of such information. Integration of climate science, impacts and vulnerability is crucial in developing coherent, context-specific adaptation responses which are cognisant of higher level mandates (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014).

In terms of the content of the climate change section in DM IDPs (, row 2), the Alfred Nzo IDP merely mentions climate change as a concern that needs to be addressed. Whilst Joe Gqabi’s IDP states that their planning is guided by the ECCCRS, the focus is limited to the common anthropogenic sources of greenhouse gases, two likely impacts of climate change in the district, and possible ways to mitigate climate change. Similarly, the Sarah Baartman IDP incorporates the ECCCRS risk assessment table, but does not include context-specific information. The Alfred Nzo, Sarah Baartman and Joe Gqabi DMs need to research the issue of climate change more thoroughly, in order to be in a more qualified position to recommend effective adaptation strategies in response to climate change. This depends on ready access to climate information and the capacity to interpret it and make it meaningful at municipal level; something that is often a stalling point (Spires & Shackleton, Citation2018).

On the other hand, Amathole, OR Tambo, and Chris Hani DMs did manage to provide more substantial information on climate change in their respective IDPs. The Amathole IDP includes descriptions of the climate of the district, context-specific climate change impacts and future projections, and possible mitigation opportunities. OR Tambo’s IDP provides clear definitions of key concepts such as global warming, climate change, adaptation and mitigation. This illustrates a more robust understanding of climate change amongst planners. Furthermore, impacts from a global to context-specific level are provided. Chris Hani’s IDP provides the most comprehensive climate change section in comparison to the other districts. Their IDP provides background information to reinforce the severity of climate change, and mentions key overarching conventions and legislation. Furthermore, simple diagrams of the greenhouse gas effect and global warming are incorporated into the climate change section. This suggests that Chris Hani is making a concerted effort to incorporate current understanding and evidence of climate change into their IDP.

4.3. Is climate change mainstreamed?

South Africa has internationally legally binding obligations to mainstream climate change considerations into social, economic and environmental policy. This has not yet been well achieved in the Eastern Cape DMs. However, in February 2012, Chris Hani hosted a District Wide Institutional Planning Session, wherein climate change was prioritised across departments in the name of mainstreaming. Although this has not yet yielded the intended results, mainstreaming of climate change is mentioned in the Chris Hani IDP. In terms of the priorities set out in the NCCRS, Chris Hani is the only municipality which mentions both mainstreaming climate change, and a detailed adaptation response strategy in its IDP. The IDPs of Alfred Nzo and Amathole do not mention mainstreaming of climate change; however, they both include evidence of a climate change response strategy. The remaining DMs, Sarah Baartman, Joe Gqabi and OR Tambo, do not include any of these objectives in their IDP. Therefore, it is fair to draw the conclusion that there is very little reference to and coordination with global and national climate change mandates across the six district municipalities and mainstreaming across sectors is not currently seen as important (, row 3).

4.4. What types of climate change interventions are mentioned?

In terms of responding to climate change, there is more of an emphasis on mitigation than on adaptation overall (, row 4). Mitigation entails reducing the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere, in order to combat climate change (IPCC, Citation2014). It is not unusual that there is a focus on mitigation, given that South Africa’s per capita emissions are high compared to other African countries (Ziervogel et al., Citation2014; Spires & Shackleton, Citation2018). However, climate change to some extent is unavoidable at this stage, and is already altering the course of social development strategies (Adger et al., Citation2003). Therefore, it is increasingly recognised that, in addition to mitigation, adaptation should form part of a central social development imperative (Adger et al., Citation2003; Ziervogel et al., Citation2014). Despite this imperative, not all DMs mention adaptation responses in their IDPs. For instance, Amathole and Joe Gqabi’s IDPs only mention mitigation measures. In addition to mitigation, the IDPs of Sarah Baartman, OR Tambo, and Chris Hani DMs do refer to some adaptation responses. However, the ECCCRS risk assessment table is included in the Sarah Baartman IDP, instead of formulating their own context-specific adaptation plan. The OR Tambo IDP refers to its spatial development framework for information on climate change adaptation responses for the district. By contrast, Chris Hani instils a sense of urgency with the regard to the implementation of adaptation responses. For example, their IDP states that ‘adaptation policies and programmes need to be implemented without delay’. Adaptation is now being afforded the same priority as mitigation in the Chris Hani IDP. Furthermore, Chris Hani recognises the importance of context-specific adaptation responses. A quote by experts during a conference on ‘Competitive Cities and Climate Change’ is included in their IDP, which states that ‘local governments are needed as partners to implement nation-wide climate change response policies, while at the same time designing their own policy responses that are tailored to local contexts.’ Providing context-specific adaptation strategies, which takes into account future climatic projections for the area, is an important step in incorporating both reactive and proactive responses to climate change to ensure sustainable adaptation (Eriksen & Brown, Citation2011; Spires and Shackleton, Citation2018).

4.5. What developmental concerns feature most strongly in the IDPs?

In terms of the main developmental concerns, (, row 5), it is evident that the social development issues of poverty and HIV/Aids are the main priorities in all of the districts. This is not an unusual finding as HIV/Aids and poverty are viewed as major concerns across the Eastern Cape and most African countries (Drimie, Citation2003). Because of their high priority, and indisputable connection, there is evidence of mainstreaming poverty and HIV/Aids across all the DM IDPs, but the link to climate change is missing.

4.6. Is there integration of climate change into the disaster risk management plan?

There is increasing scientific evidence regarding the ways in which climate change will exacerbate the frequency and intensity of natural disasters (Mercer, Citation2010; IPCC, Citation2014; Hallegatte et al., Citation2017). However, the link between climate change and these disasters are not being made in most DM IDPs, with little mention of climate change in the disaster risk management section of the IDPs (, row 6). Moreover, the disaster risk management sections in DM IDPs are all reactive in nature and do not mention proactive adaptation responses. Chris Hani’s IDP is the only one which mentions responses to climate change as a main concern in its disaster management plan. The other municipalities only indirectly manage the impacts of climate change through disaster risk management, by mentioning plans to reduce the effects of natural disasters.

4.7. What priority is afforded to climate change?

The relative priority each DM afforded to climate change was established and assigned a score (, row 9). Chris Hani DM places a high priority on climate change, while Amathole, Sarah Baartman and OR Tambo were found to afford a medium priority to this issue. On the other hand, Alfred Nzo and Joe Gqabi DMs showed limited engagement with climate change. The small size of the DMs and the possible lack of people with the knowledge and capacity to incorporate climate change into the various development sectors across the IDP, may be one of the main reasons why climate change is not prioritised and mainstreamed in the district. However, as shown by Spires & Shackleton (Citation2018) and the Pasquini et al. (Citation2013) there may be multiple barriers preventing the mainstreaming of climate change into IDPs. Further research with officials from these municipalities would be needed to really unpack this.

4.8. Are vulnerability and poverty mentioned in relation to climate change?

Although DMs do not include climate change in sectors dealing with social development issues, most IDPs do make the connection between poverty, vulnerability and climate change in their environmental management sections (, row 8). Joe Gqabi is the only district which does not mention these issues in relation to climate change in their IDP. Although very brief, the Alfred Nzo IDP suggests that vulnerability mapping and climate change needs to be addressed. The OR Tambo IDP indirectly deals with the concepts of vulnerability and poverty, by recognising that climate change ‘is already having and will continue to have far reaching impacts on human livelihoods.’ This was stated as the reason why OR Tambo should focus on both mitigation and adaptation responses. Additionally, it is explicitly stated in the OR Tambo IDP that the harmful impacts of climate change will place a ‘greater burden on particularly impoverished communities.’ In the Chris Hani IDP, poverty is identified as one of the underlying conditions which has the power to magnify or moderate the impacts of climate change. Vulnerability and risk forms the framing in which the impacts of climate change need to be considered in the Amathole IDP. Finally, the Sarah Baartman IDP offers the most attention to the issues of vulnerability and poverty, in comparison to the other districts. It is recognised that the impacts of climate change will affect the environmental, economic and social systems of the district. For this reason, it is emphasised that successful outcomes of development plans, particularly in regard to poverty alleviation and food security, will increase the resilience of vulnerable communities to climate change. In other words, this will build the generic capacity of a community, which has been identified as one of the crucial components in formulating effective adaptation responses to climate change (Eakin et al., Citation2014). It is evident that, on a DM level, the links between vulnerability, poverty and climate change are slowly beginning to form. However, these convergences need to be more explicit in order to simultaneously increase adaptive capacity to climate change, and realise sustainable development goals (Eakin et al., Citation2014).

4.9. Are there improvements from earlier IDPs?

With regard to whether there is progress from earlier IDPs to the latest available IDPs, not all DMs show an improvement concerning the climate change section in their latest IDP (, row 9). For example, Alfred Nzo’s 2014/2015 IDP eliminated all mention of mainstreaming climate change and links with vulnerability, which was present in the 2011/12 IDP. The Amathole 2014/2015 IDP is another example of a district IDP whose climate change section was more comprehensive, and focused on building both generic and specific adaptive capacities, in earlier years. The complexity of climate change was acknowledged and grappled with in the 2011/2012 IDP, but is absent in the 2014/2015 IDP. On the other hand, the Chris Hani, Joe Gqabi and OR Tambo districts show an improvement in terms of the content contained in their latest IDPs. Finally, Sarah Baartman has made no changes to the climate change section from in their 2014/2015 IDP review.

Progress over time is a crucial indicator of a DM that is engaging critically and consistently with the complexity of climate change. However, frequent staff turnover and a lack of institutional memory have been cited as common barriers to continuity in municipal planning for climate change (Spires et al., Citation2014).

4.10. Do DM IDPs inform climate change planning in LM IDPs?

It is important that what is prioritised in DMs is passed down to LMs, to ensure coherency and the fulfilment of higher level mandates, and this includes plans on climate change. On a LM level, only 47% of municipalities refer to climate change in their latest IDPs available on the internet (). It is of concern that 53% of local municipalities do not mention climate change at all.

Table 3. Incorporation of climate change in Eastern Cape local municipal IDPs.

Despite Chris Hani’s IDP having the most comprehensive climate change section, half of the LMs’ IDPs in this district do not mention climate change. Contrastingly, only one of the LMs in the Alfred Nzo DM does not mention climate change, despite Alfred Nzo having the least information on climate change in their IDP. Therefore, there appears to be little effort at ensuring a coherent vertical linkage between the district and local level.

4.11. Is there evidence of financial planning to support climate change adaptation activities?

Mentioning climate change adaptation in the IDP is not enough on its own; if municipalities do not set aside financial resources for climate change related activities, implementation will not happen and it will remain an abstract concept. Out of the IDPs for the six DMs, only three mentioned the need for funding climate change activities, and out of these only one showed evidence of allocating specific funding to climate change.

Alfred Nzo DM’s IDP specified that they were allocating R400 000 to their climate change adaptation strategy in 2016/17, R424 800 in 2017/18 and R449 863 in 2018/19, to be shared amongst all local municipalities in the district (Alfred Nzo DM IDP, 2016/17). The source of this funding was the Equitable Share, a grant that all municipalities receive from National Treasury to use at their discretion. Interestingly, their IDP was one of the weaker ones regarding mention of climate change and adaptation. This suggests they are aware of this gap and taking the necessary steps to amend it.

Chris Hani DM’s IDP mentioned that the municipality had developed a climate change strategy which was adopted by Council in 2012/13, and that one of the decisions taken by Council was to allocate funds for this strategy to each LM; but no details were given of the source or quantity of this funding (Chris Hani DM IDP, 2016/17). Amathole DM’s IDP detailed the assistance that the DM had provided to farmers during the recent droughts, for example through the distribution of rainwater tanks, and reflected that much more was needed, and that many more resources need to be channelled towards preparing farmers and communities for climate change (Amathole DM IDP, 2016/ 17). However no specific funding for climate change adaptation was mentioned. The IDPs for O. R. Tambo DM, Sarah Baartman DM and Joe Gqabi DM made no mention of budget for climate change adaptation in their 2016/17 IDPs. This indicates that planning for climate change in these municipalities is likely to remain at the level of rhetoric or that funding would need to be sought from other sources.

4.12. Can DM IDPs be said to support sustainable adaptation to climate change?

There are varying degrees to which each DM supports adaptation to climate change for the most vulnerable communities. A comparison across all six districts is provided in . The highest possible score was 27. These ratings indicate the ranking of the DMs in this study relative to one another, and do not indicate an objective score relative to all DMs in the country.

Figure 4. Ranking of district municipalities in terms of enabling sustainable adaptation of vulnerable communities to climate change.

In light of the nine core themes, it can be inferred that Chris Hani is the leader in terms of providing the conditions to support sustainable adaptation to climate change. The climate change section in the Chris Hani IDP highlights the significance of climate change, the impacts from a global to context-specific level, and the importance of both mitigation and adaptation measures. Furthermore, the concept of mainstreaming is being supported in the district’s Climate Change Strategy, and evidence of climate change adaptation projects are provided for. The OR Tambo DM is moving towards facilitating sustainable adaptation to climate change. Their IDP shows clear research on the topic of climate change and has explored its impacts from a global to local level. In addition, the link between climate change and human livelihoods and well-being is made. This is a first step towards incorporating climate change into social development issues, which consequently builds generic adaptive capacity. Furthermore, both mitigation and adaptation methods are regarded as essential. However, no direct measures for adaptation have been stipulated in their IDP but it does lay the necessary groundwork for such plans to be formulated.

On the other hand, the Alfred Nzo, Amathole, Sarah Baartman, and Joe Gqabi DMs do not adequately support sustainable adaptation to climate change. This is because climate change is viewed solely as an environmental issue, and there is no evidence of mainstreaming climate change across sectors in their IDPs. In addition, the Joe Gqabi and Amathole IDPs do not mention adaptation responses in the climate change section. Alfred Nzo does not include any interventions to climate change in their IDP, although their budgeting suggests that they are working on this.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The international, national and provincial policy landscape has clear mandates for mainstreaming climate change, and incorporating detailed adaptation responses into all municipal planning processes. However, like in many other parts of the world, these requirements have not been adhered to across DMs in the Eastern Cape. Furthermore, what is incorporated on climate change at district level, does not seem to inform whether or not this issue is mentioned at a LM level. The South African government has provided a set of guidelines for integrating climate change into municipal planning through the Lets Respond Toolkit (DEA, Citation2012). However, a toolkit on its own is clearly insufficient.

More robust and appropriate support, for mainstreaming climate change and adaptation strategies into IDPs is needed. This should take consideration of the limited capacity and resources of small semi-rural municipalities such as the ones reviewed here. Crucially, planning and support for climate change needs to extend to financial planning and the allocation of budget for implementing the practical activities contained in local plans. Increasing the priority of climate change in developing countries’ policies and plans, thus requires much more technical background work (Mertz et al., Citation2009), as well as ‘soft skills’ such as participatory facilitation. Furthermore, for such ideals to be realised, several strategies are needed to inform appropriate adaptation responses: (a) communication and coherency between of all levels of government needs to be improved and climate change mainstreamed across sectors (Dazé et al., Citation2016; Spires & Shackleton, Citation2018); (b) increased participation of local communities in planning processes is essential, so as to understand their perceptions of climate change, the multiple stressors they face and their local practices (Reid et al., Citation2015); (c) the barriers municipalities face need to be fully understood and mechanisms to overcomes them addressed (Pasquini et al., Citation2013); and (d) inputs of climate change specialists with knowledge of the latest state of the art projections and impacts are needed to ensure adequate information to inform adaptation options and the building of specific adaptive capacity (Spires et al., 2013). Moreover, failure to integrate climate change adaptation with development policy and plans, as well as disaster risk reduction, may result in misrepresentations and inefficiencies that threaten long-term sustainable development (Agrawala, Citation2004; Bizikova et al., Citation2007; Lemos et al., Citation2013). Therefore, it is crucial that developing countries like South Africa should prioritise innovative approaches to integrating climate change adaptation into subnational planning and social development processes to create an enabling environment for supporting sustainable adaptation that builds both generic and specific adaptive capacity amongst vulnerable communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adger, WN, Huq, S, Brown, K, Conway, D & Hulme, M, 2003. Adaptation to climate change in the developing world. Progress in Development Studies 3(3), 179–95. doi: 10.1191/1464993403ps060oa

- Agrawala, S, 2004. Adaptation, development assistance and planning: Challenges and opportunities. IDS Bulletin 35(3), 50–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2004.tb00134.x

- Aylett, A, 2014. Progress and challenges in the urban governance of climate change: Results of a global survey. MIT, Cambridge, MA.

- Bizikova, L, Robinson, J & Cohen, S, 2007. Linking climate change and sustainable development at the local level. Climate Policy 7(4), 271–77. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2007.9685655

- Conway, D & Mustelin, J, 2014. Strategies for improving adaptation practice in developing countries. Nature Climate Change 4, 339–42. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2199

- Dazé, A, Price-Kelly, H & Rass, N, 2016. Vertical integration in national adaptation plan (NAP) processes: A guidance note for linking national and sub-national adaptation processes. International Institute for Sustainable Development, Winnipeg, Canada. www.napglobalnetwork.org.

- DEA (Department of Environmental Affairs), 2013. Long-term adaptation scenarios flagship research programme (LTAS) for South Africa. Climate Trends and Scenarios for South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa.

- DEA (Department of Environmental Affairs), 2016. Draft South African national climate change adaptation strategy. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- DEA (Departmental of Environmental Affairs), 2012. Let’s respond toolkit: Guide to integrating climate change risks and opportunities into municipal planning. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Drimie, S, 2003. HIV/aids and land: Case studies from Kenya, Lesotho and South Africa. Development Southern Africa 20(5), 647–58. doi: 10.1080/0376835032000149289

- Eakin, HC, Lemos, MC & Nelson, DR, 2014. Differentiating capacities as a means to sustainable climate change adaptation. Global Environmental Change 27(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.013

- ECCCRS (Eastern Cape Climate Change Response Strategy), 2011. Department of economic development and environmental affairs. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Engelbrecht, FA & Landman, W, 2013. Current climate. In South African vulnerability atlas. Department of Science and Technology, Government Printer, Pretoria, pp. 6–14.

- Eriksen, S & Brown, K, 2011. Sustainable adaptation to climate change. Climate and Development 3(1), 3–6. doi: 10.3763/cdev.2010.0064

- Eriksen, S, Aldunce, P, Bahinipati, CS, Martins, RDA, Molefe, JI, Nhemachena, C, O’Brien, K, Olorunfemi, F, Park, J, Sygna, L & Ulsrud, K, 2011. When not every response to climate change is a good one: Identifying principles for sustainable adaptation. Climate and Development 3(1), 7–20. doi: 10.3763/cdev.2010.0060

- Glaas, E, Jonsson, A, Hjerpe, M & Andersson-Sköld, Y, 2010. Managing climate change vulnerabilities: Formal institutions and knowledge use as determinants of adaptive capacity at the local level in Sweden. Local Environment 15(6), 525–39. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2010.487525

- Hallegatte, S, Vogt-Schilb, A, Bangalore, M & Rozenberg, J, 2017. Unbreakable: Building the resilience of the poor in the face of natural disasters. Climate Change and Development, World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Harris, PG, 2010. World ethics and climate change: From international to global justice. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), 2014. Summary for policymakers. In Barros, VR, Dokken, DJ, Mach, KJ, Mastrandrea, MD, Bilir, TE, Chatterjee, M, Ebi, KL, Estrada, YO, Genova, RC, Girma, B, Kissel, ES, Levy, AN, MacCracken, S, Mastrandrea, PR & White, LL (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, pp. 1–30.

- Kok, MTJ & De Coninck, HC, 2007. Widening the scope of policies to address climate change: directions for mainstreaming. Environmental Science & Policy 10(7), 587–99. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2007.07.003

- Lemos, MC, Agrawal, A, Eakin, H, Nelson, DR, Engle, NL & Johns, O, 2013. Building adaptive capacity to climate change in less developed countries. In Asrar, GR & Hurrell, JW (Eds.), Climate science for serving society: Research, modelling and prediction priorities. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp. 437–57.

- Le Roux, A & Van Huyssteen, E, 2013. The South African socio-economic and settlement landscape. In South African vulnerability atlas. Department of Science and Technology. Government Printer, Pretoria, pp. 15–19.

- LTAS, 2013. The South African long term adaptation scenarios. Department of Environmental Affairs. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Measham, TG, Preston, BL, Smith, TF, Brooke, C, Gorddard, R, Withycombe, G, & Morrison, C, 2011. Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: Barriers and challenges. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 16(8), 889–909. doi: 10.1007/s11027-011-9301-2

- Mercer, J, 2010. Disaster risk reduction or climate change adaptation: Are we reinventing the wheel? Journal of Sustainable Development 22, 247–64.

- Mertz, O, Halsnæs, K, Olesen, JE & Rasmussen, K, 2009. Adaptation to climate change in developing countries. Environmental Management 43(5), 743–52. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9259-3

- Monkam, NF, 2014. Local municipality productive efficiency and its determinants in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 31(2), 275–98. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.875888

- NCCRWP (National Climate Change Response White Paper), 2011. The South African national climate change response white paper. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- NDP (National Development Plan), 2011. The South African national development plan. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Pasquini, L, Cowling, RM & Ziervogel, G, 2013. Facing the heat: Barriers to mainstreaming climate change adaptation in local government in the Western Cape province, South Africa. Habitat International 40, 225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.05.003

- Pasquini, L, Ziervogel, G, Cowling, RM & Shearing, C, 2015. What enables local governments to mainstream climate change adaptation? Lessons from two municipal case studies in the Western Cape, South Africa. Climate and Development 7, 60–70. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2014.886994

- Picketts, IM, Déry, SJ & Curry, JA, 2014. Incorporating climate change adaptation into local plans. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 57(7), 984–1002. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2013.776951

- Reid, H, Alam, M, Berger, R, Cannon, T, Huq, S & Milligan, A, 2009. Community-based adaptation to climate change: An overview. In IIED (Eds.), Participatory learning and action 60: Community-based adaptation to climate change. Russell Press, Nottingham. pp. 11–33.

- Reid, H, Swiderska, K, King-Okumu, C & Archer, D, 2015. Vulnerable communities: Getting their needs and knowledge into climate policy. IIED Briefing, November 2015. IIED, London. http://pubs.iied.org/17328IIED.

- Roberts, D, 2008. Thinking globally, acting locally — institutionalizing climate change at the local government level in Durban, South Africa. Environment & Urbanization 20(2), 521–37. doi: 10.1177/0956247808096126

- Roberts, D, 2013. Cities OPT in while nations COP out: Reflections on COP18. South African Journal of Science 109(5/6), 1–3. Art. #a0014, 3. doi: 10.1590/sajs.2013/a0014

- Shackleton, S, Ziervogel, G, Sallu, S, Gill, T & Tschakert, P, 2015. Why is socially-just climate change adaptation in sub-Saharan Africa so challenging? A review of barriers identified from empirical cases? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 6, 321–344.

- Spires, M, & Shackleton, S, 2018. A synthesis of barriers to and enablers of pro-poor climate change adaptation in four South African municipalities. Climate and Development 10(5), 432–447. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2017.1410088

- Spires, M, Shackleton, S & Cundill, G, 2014. Barriers to implementing planned community-based adaptation in developing countries: A systematic literature review. Climate and Development 6(3), 277–87. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2014.886995

- Statistics South Africa, 2017a. Poverty trends in South Africa: An examination of absolute poverty between 2006 and 2015. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria. Report No. 03-10-06. 138 pp.

- Statistics South Africa, 2017b. Mid-year population estimates 2017. Statistical release P0302. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022017.pdf. Accessed 1 February 2018.

- Stokey, E & Zeckhauser, R, 1978. A primer for policy analysis. Norton & Company, New York.

- Ziervogel, G, New, M, Archer van Garderen, E, Midgley, G, Taylor, A, Hamann, R, Stuart-Hill, S, Myers, J & Warburton, M, 2014. Climate change impacts and adaptation in South Africa. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 5(5), 605–20.