ABSTRACT

This article considers a developing country which is abundant in a non-renewable natural resource but scarce in industrial goods. The resource can be used for consumption or for exporting ecotourism services. The article examines scenarios in which technical progress, rising demand for tourism services and higher preferences for the environment reduce today's optimal depletion of the resource. Myopic behaviour and future terms-of-trade gains, however, encourage overexploitation of the resource. As a remedy, the article derives the socially optimal subsidy for the conservation of the resource and discusses North–South transfer schemes which save nature via trade in ecotourism services. Numerical examples suggest that under optimistic assumptions a subsidy rate of about 10% would suffice to preserve the natural resource in the developing country for the provision of tourism services. The resulting cost burden would represent less than 0.03% of the Northern GDP.

Significance

The article provides new insights in the future development of (eco-) tourism in developing countries and corresponding policies.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the largest sectors world-wide. The value of world-wide exports of travel services has been continuously growing during the last decades (see Figure A4 in the Appendix). While the growth of tourism is most likely to persist, the natural resourcesFootnote1 that create attractive destinations for tourists are not expanding but in danger of being irretrievably depleted. Natural resources, such as unspoilt beaches, coral reefs, rainforests, savannahs, or natural lakes with their rich biodiversity and wildlife require very long time horizons to recover and cannot be replaced by human activity. Hence, taking into account that unique natural resources are often found in poor developing countries in the sub-tropical and tropical zone, we ask the question whether and how such non-renewable resources can be conserved in order to provide future tourism services, particularly for consumers residing in industrialised or emerging countries.

If natural resources are depleted today, this will not only be harmful from an environmental perspective, but also from an economic welfare perspective. Therefore, the following article focuses on tourism that seeks nature and aims at conserving nature, the so-called ecotourism Footnote2 (ecological tourism). Ecotourism is becoming ever more popular. South Africa, comprising about 20 national parksFootnote3 that attracted almost five million visitors (PMG, Citation2012) in the season 2011/12 with an upward trend, is a prominent example (cf. Figure A5 in the Appendix).Footnote4

It seems, however, that the expected future demand for nature-related tourism services cannot be satisfied because of the exploitation and destruction of nature for today's consumption. Virunga National Park, located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, is Africa's oldest national park but under pressure due to deforestation and plans for oil depletion. Another example is the Brazil Amazon rainforest with its immense biodiversity. This unique natural resource is under pressure because of forest clearance for agriculture, large-scale depletion of soil resources and large-scale hydro power projects that provide the energy for resource extraction and production.

Against this backdrop, the following analysis will show which policy intervention is required to preserve the natural resources for future generations to avoid welfare losses, for both developing and industrialised countries. The analysis focuses on the positive connection between tourism and nature and has a future perspective. To this end, it sketches three scenarios of developments that are expected to enhance future tourism: (1) technological progress and the resulting reduction in transportation costs; (2) population growth in emerging economies and rising global per-capita income resulting in an increasing number of tourists; (3) preference shifts and economic restructuring in developing countries and the resulting less natural resource-intensive production.

We first imagine a developing country (South) which can exploit a non-renewable natural resource for consumption or conserve if for the provision of tourism services. In exchange for exporting tourism services, it imports industrial goods from industrialised or emerging countries (North). We then introduce a South–North framework. This allows us to address the following research questions: How does future tourism affect today's depletion of natural resources? Which policies should be pursued to achieve the social optimum? How can policy costs be shared between the developing countries providing tourism services and the industrialised countries seeking tourism services so that a win-win situation is achieved?

We will see how future tourism influences today's resource use with respect to intertemporal optimality. The anticipation of rising demand for ecotourism services raises today's shadow price of the natural resource and provides incentives to preserve it. However, myopic behaviour and a terms-of-trade effect, that has been neglected so far, work against resource preservation: the overexploitation of the natural resource for the sake of higher consumption today improves the terms-of-trade in favour of the exporters of tourism services in the future. As a solution, we propose a subsidy for resource preservation that mimics the optimal shadow price. We also show that industrialised countries have an economic incentive to support the preservation of the resource by (co-)financing the subsidy.

The following article builds on the discussion paper by Hübler (Citation2015) and proceeds as follows. Section 2 positions the article within the literature. Section 3 introduces ecotourism scenarios based on an economic model, while the Appendix describes mathematical details. Section 4 studies the impact of these scenarios on future tourism in the South and derives the optimal forward-looking policy. Section 5 introduces the North and derives policy options that make both the South and the North better off. The key policy results are illustrated with exemplary numbers. Section 6 concludes with a detailed policy discussion.

2. Literature

This section positions the article within related literature streams.

2.1. Tourism-trade models

This article is closely related to the literature exploring tourism by means of trade models.

Hazari & Sgro (Citation2004) provide an overview of tourism studies based on models of international trade looking at welfare effects, immiseration, immigration, taxation, price discrimination or dynamic growth effects. Several theoretical studies have identified a ‘Dutch Disease’ effect of inward tourism (Copeland, Citation1991; Adams & Parmenter, Citation1995; Nowak et al., Citation2003; Chao et al., Citation2006): on the one hand, as argued by this literature, a tourism boom can have negative effects on other sectors of the economy like agriculture, mining or manufacturing so that the overall economy can end up worse off. Likewise, Hazari & Lin (Citation2011) argue that inward tourism can make the poor worse off. As a consequence of the negative effects of tourism, tourism should be taxed. On the other hand, this literature highlights that in contrast to trade in goods, tourism fosters the demand for local non-tradable goods, for example, services provided by hotels, restaurants and local travel agencies, so that the overall economy can become better off (Copeland, Citation1991). Likewise, Chao et al. (Citation2009) argue that inward tourism can convert non-tradable goods into tradable goods and in this way generate a positive terms-of-trade effect that makes the economy better off. Different to the terms-of-trade effects and sectoral shifts examined in the one-country models of this literature, the following analysis concentrates on the long-term nexus between tourism and the exploitation of natural resources in developing countries and explores a new terms-of-trade effect that has been neglected so far: myopic overexploitation of the natural resource today improves the terms-of-trade in favour of the exporters of tourism services tomorrow. In order to analyse the terms-of-trade effects from a welfare perspective, we introduce a two-country framework.

Environmental aspects of tourism have hardly been addressed by scholars of the trade modelling school. Cerina (Citation2008), as a notable exception, studies tourism related to environmental resources in a dynamic general equilibrium model. The model allows him to examine different abatement policies. Instead of a dynamic model with environmental resources, Beladi et al. (Citation2009) present a static model, in which tourism can be exogenous or endogenous and generates pollution. This allows them to derive the optimal pollution tax taking inward tourism into account. The main difference between these studies and the analysis carried out in the following is that the existing studies focus on the detrimental environmental effects of tourism via pollution. The following analysis, on the contrary, moves the spotlight to the environmentally beneficial side of tourism, even though detrimental effects of tourism are also taken into consideration. This view is especially apposite for ecotourism and the interrelation between economic development, policy intervention and long-term effects of tourism.

2.2. Ecotourism literature

In contrast to the lack of model-based studies of ecotourism, a large literature of case studies of ecotourism has emerged. The following paragraphs provide recent examples focusing on sustainable development of Southern Africa and highlight some challenges.

Rogerson (Citation2007) emphasises the small but increasing role of Southern Africa in world tourism and proposes the development of new policies and initiatives. Ecotourism is deemed to be such an option. Referring to Zimbabwe, Muzvidziwa (Citation2013) defines ecotourism as nature conservation by means of utilisation including consumption and non-consumption values. Krstic et al. (Citation2016) emphasise the importance of tourism for Southern African countries with regard to international competitiveness. Similarly, Snyman (Citation2017) underlines the important role of private sector ecotourism in Southern Africa's sustainable socio-economic development including job creation. Likewise, Dikgang & Muchapondwa (Citation2017) identify significant additional revenues and incentives for nature conservation for adjacent communities generated by national parks in South Africa.

Besides these opportunities, however, ecotourism involves serious challenges. Particularly, Uddhammar (Citation2006) as well as Shoo & Songorwa (Citation2013) point to distributional and managerial difficulties of implementing tourism in a sustainable way. Thus, scholars think about ways to tackle these challenges. Referring to Japan, Hara & Iwamoto (Citation2014) propose an ecotourism certification system. Referring to China, Min (Citation2015) proposes a value compensation mechanism to achieve economic development with the help of ecotourism.

2.3. Economics literature

From a broader perspective, the article is related to three established literature streams in economics: the literature on international trade and the environment, the literature on economic growth and the environment, and the literature on tourism and the environment.

The first literature stream has surveyed under which conditions free trade is good for the environment and under which conditions it can result in the (full) exhaustion of a non-renewable resource (for an overview see Copeland & Taylor (Citation2003); for influential contributions see Grossman & Krueger, Citation1993; Antweiler et al., Citation2001). The literature on trade and the environment assumes that international trade, often in combination with international factor mobility, draws on natural resources to produce goods. In particular, the pollution-haven hypothesis states that globalisation shifts pollution- and resource-intensive production to developing countries with low environmental regulation (e.g. Janicke et al., Citation1997; Levinson & Taylor, Citation2008). In contrast, the following analysis assumes that a developing country is dependent upon a non-renewable natural resource for consumption in autarky. Opening up to trade enables it to preserve part of the resource so that it can export tourism services derived from the natural resource without depleting the resource.

The second literature stream has scrutinised under which conditions economic growth driven by technical progress and population growth can be sustained without instantaneously increasing emissions or without fully exhausting a natural resource (for overviews see Smulders, Citation1999; Xepapadeas, Citation2005). Such a development is sometimes called ‘green growth’. According to the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis (based on Kuznets, Citation1955; e.g. Stern, Citation2004), the following analysis assumes that the preference for environmental quality, in this case for the natural resource, increases in (per-capita) income. This effect is called income effect or (income-induced) technique effect (cf. Antweiler et al., Citation2001). It implies that more of the resource will be preserved for future societies when income rises today. Specifically, the following analysis assumes that exogenous technical progress, population growth and per-capita income growth amplify the supply of and the demand for tourism, which adds a new channel of ‘green growth’.

The third literature stream has studied the impact of tourism on economic performance and growth at the sectoral and macroeconomic level (for overviews see Tisdell, Citation2001; Dwyer & Forsyth, Citation2006; Stabler et al., Citation2010; Matias et al., Citation2011). It has contrasted the benefits of tourism with its negative external effects on the public good, the environment (nature), and sought the optimal level and way of tourism. This literature has also disentangled the drivers of tourism demand and supply in order to forecast future tourism. Transportation costs, population size and income are identified as important drivers of tourism demand (cf. Dwyer & Forsyth, Citation2006, chapter 1). These drivers will be included in the following.

3. Scenarios

Three aspects are expected to significantly change future tourism and as a repercussion today's resource use. To assess these aspects, we formulate scenarios and analyse their impact on the model equilibrium (see Equation (15) in the Appendix). Following the literature using tourism models (Copeland, Citation1991; Hazari & Sgro, Citation2004), we assume the demand for tourism services is given. The model solution follows Jakob et al. (Citation2013).

3.1. Technical progress

Transportation technologies have experienced considerable technical progress. In the future, breakthrough technologies and gradual technical progress can be expected to further reduce travel costs and to reduce emissions stemming from the transport sector as well. This includes direct travel costs in form of monetary payments as well as indirect monetised costs in terms of reduced travel time and risks like accidents. Likewise, upgraded national transportation infrastructure in developing countries can improve access to remote ecotourism areas.

As a consequence, developing countries will be able to provide more tourism services, and consumers of tourism services will obtain more services in value terms given a specific travel cost. As a result, the future (second-period) production possibility frontier, , will shift outward towards the provision of more tourism services, T, relative to the natural resource, E, in the model; i.e. the developing country can provide more units of tourism services net of direct and indirect travel costs. Regarding E, one can imagine rainforests, savannahs, natural lakes, unspoilt beaches, coral reefs, and so forth. Due to their rich biodiversity and their natural uniqueness, these natural resources cannot be replaced by human activity and are hence treated as non-renewable. Due to the technical progress, the optimal subsidy, σ, that will be defined later in Equation (Equation1

(1) ), becomes larger. As a result, the slope of the tangent in will become smaller (less negative). Thus, the tangency point with the production possibility frontier of period one will move to the left, and a smaller amount of the resource will be consumed today, while a larger amount will be preserved for future tourism. At the same time, production and income will rise in the second period because of the technical progress. Thus, in , the production possibility frontier is stretched upwards so that more T can be generated given a specific resource endowment.

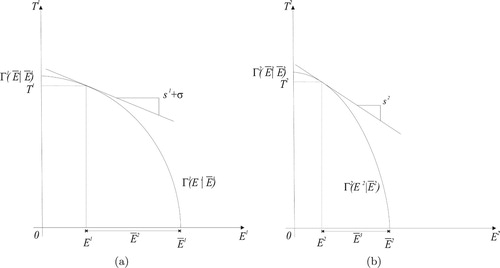

Figure 1. Tourism boom.

Notes: In the forward-looking trade case with booming future tourism, the second-period price for tourism services is even higher than in the forward-looking case. Hence, the slope of the tangent, consisting of the first-period price and the shadow price σ, is even lower in the first period, i.e. less negative, in (a) than in the forward-looking case. As a result, a minor part of the resource stock is consumed in the first period, indicated by

in (a), and the major part is available for tourism and for the second period, indicated by

in (a) and (b).

3.2. Economic growth

In the future, the population of emerging economies will grow, and the per-capita income levels of industrialised as well as emerging economies will increase (OECD, Citation2008; Chateau et al., Citation2011). In the light of projected income and population growth, ecotourism is expected to increase. This expectation follows the environmental Kuznets curve literature (Kuznets, Citation1955; for a more recent and critical discussion see Stern, Citation2004). It can also be derived from the stylised fact that the preference of consumers for enjoying the environment rises with higher per-capita income. This is known as the income effect or the income-induced technique effect in the literature (following Antweiler et al., Citation2001; based on Grossman & Krueger, Citation1993).

These demographic and economic developments will ceteris paribus jointly result in higher demand for tourism services by the rest of the world and thus in a higher future (second-period) world market price for tourism services, , provided by developing countries. In Equation (Equation1

(1) ), a higher

will increase σ and hence also reduce the slope of the tangent in . Again, a smaller amount of the resource will be consumed today, while a larger amount will be preserved for future tourism. Due to the rising demand and higher world market price for future tourism, the slope,

, is flatter than

in , and it is flatter than

in Figure A3(b) in the Appendix as well.

3.3. Preference shift

The preferences of Southern economies can be expected to shift away from natural resource consumption towards natural resource conservation and industrial goods consumption in the course of economic development. This assumption is motivated by the environmental Kuznets curve and the income-induced technique effect, as in the previous subsection. At the micro level, this assumption is also related to the observation that people living in rural low-income economies mainly depend on the exploitation of natural resources for subsistence farming. This dependence on the exploitation of natural resources, however, weakens with economic development and the transition from agriculture to industry. The (marginal) utility drawn from the consumption of the natural resource declines relative to the (marginal) utility drawn from the consumption of industrial goods.

This third mechanism acts in the same direction as the first two mechanisms. Now the marginal utility of future (second-period) industrial goods consumption rises relative to that of today's industrial goods consumption

, so that σ defined by Equation (Equation1

(1) ) increases. Again, more of the resource will be preserved for future tourism. This mechanism is depicted by as well.

Notably, the three aspects positively interact with each other, i.e. they enhance each other in a complementary way, as indicated by their multiplicative connection, which will be taken into account in the following.

4. Policy

Taking into account these future developments, this section shows how a policy instrument can be designed in order to achieve the optimal solution for the developing country in the absence of other market failures. It also provides crude numerical estimates of the policy effects under scrutiny in order to illustrate the relevance of the results.

4.1. Optimal instrument

In reality, we often observe trade with myopic behaviour that neglects future developments of tourism. As a result, the resource stock left for period two is considerably lower than what is socially optimal. The optimal policy instrument, σ, leads from the myopic case to the socially optimal forward-looking case and can be derived by comparing Equation (15) with (12), both detailed in the Appendix. For achieving the forward-looking (social) welfare maximum, the optimal policy supports the provision of tourism services via the following additive (dimensionless) subsidyFootnote5 defined over periods :

(1) The optimal subsidy, σ, manipulates the exogenous relative prices,

, in such a way that tourism services, T, become relatively more valuable. σ adjusts the (theoretical forward-looking) shadow price of tourism services. σ depends on the marginal utilities,

,

and

, which depend on the quantities of the consumed good, I, and the natural resource, E (in a non-linear way). Hence, the optimal subsidy is expressed given a specific reference point with corresponding marginal utilities.Footnote6 The future (second-period) production possibility frontier is denoted

. Higher discounting of the future, reflected by a smaller value of ρ, reduces the value and the relevance of σ. The subsidy rate, σ, is added to the price ratio characterised by Equation (12); it modifies the inverse relative price for tourism services, T, in such a way that the optimal amount of the resource, E, is left for the future.Footnote7

The subsidy rate, σ, consists of two additive components, each multiplied by the discounting factor, ρ. The first additive component, describes the value of future resource consumption for the South. It states that a lower price for tourism services today, a higher marginal utility of resource consumption in the future (relative to the marginal utility of the industrial good today) and a higher reduction of future consumption via consumption today result in a higher σ.

In exchange for consuming the industrial good, the South needs to provide tourism services. Accordingly, the second additive component describes the value of future industrial good consumption for the South. The second component consists of three multiplicative terms which characterise future tourism-related technical progress, (a dimensionless marginal term relating to the scenario of future tourism as described in Section 3.1), the future price for tourism services relative to today's price associated with rising demand,

(a dimensionless price ratio relating to the scenario in Section 3.2), and the resource-rich developing economy's future preference for the industrial good relative to its preference today,

(a dimensionless ratio relating to the scenario in Section 3.3).

As described in the previous section, it is likely that technical progress in transportation will continue, the demand for tourism services and hence their price will increase, and the preferences of developing countries will shift toward consuming industrial goods. If these future developments are not taken into account by developing countries, e.g. because of missing information or political constraints, it will be economically reasonable to subsidise the conservation of natural resources for future tourism by taking the change in the variables relating to the three scenarios in Equation (Equation1(1) ) into account. The case of forward-looking trade without these future developments would then provide the benchmark for the subsidy. Accordingly, if no value is attributed to conserving the natural resource for future tourism at all, e.g. due to extreme poverty, then optimal policy intervention needs to take the absolute values of the variables in Equation (Equation1

(1) ) into account. The case of myopic trade without future developments related to the three scenarios would then provide the benchmark for the subsidy.

4.2. Numerical example

This section illustrates the policies discussed in the last subsection based on the stylised model, particularly Equations (1) and Appendix (15), in an exemplary way. Specifically, it provides admittedly crude estimates of the required subsidy to give an idea of its economic magnitude and policy relevance under alternative assumptions for the South that may either ignore, or account for the value of future tourism.

Let us for simplicity set all prices (price ratios) and marginal utilities to one. Then, based on Equation (15) we obtain , which represents a consumption point as depicted by Figure A2(a) in the Appendix. Based on this consumption point, let us assume that about two thirds or 66% of the resource remaining in period two are used for consumption and the remaining third or 33% for tourism. This assumption translates into

and

in Equation (Equation1

(1) ). When choosing a discount rate for the second period, we need to consider that we project a long future time period onto the second period. Let us assume a low annual discount rate of 1%. Then over 120 years, we obtain

. With these exemplary values, Equation (Equation1

(1) ) yields

. Under these assumptions, the additive subsidy will reduce the original price ratio,

, by 30% to

. This implies a relatively high subsidy rate and a relatively strong policy effect.

However, the assumption that the value of future tourism is not at all acknowledged by the South is extremely pessimistic. Let us instead imagine that the South takes account of for the sake of its own future welfare, but does not anticipate the future developments of tourism described in Section 3. This might be due to poverty reasons or lack of information about the future. Regarding the scenario of technical progress in the tourism sector (Section 3.1), let us assume that one unit of the natural resource conserved today does not generate 0.33 units of future tourism (

) as previously assumed, but 0.5 units (

). Regarding the scenario of demand and prices in the tourism sector (Section 3.2), we refer to Figure A5 in the Appendix. The underlying data yield an average annual increase in the number of tourists heading for South Africa between 1992 and 2012 of about 8.3%. We choose South Africa as an example because tourism seeking for nature and wildlife plays a major role in this country. Under the assumption that the price elasticity of demand for tourism services equals unity, this translates into an annual price increase for tourism services of the same amount. This leads to

. Regarding the scenario on preference shifts (Section 3.3), we may use the decline in the share of agricultural value added in South Africa's GDP as a proxy for the change in marginal utilities of the consumption of the natural resource and industrial goods: according to WDI (Citation2014), this share decreased by about 2.6% annually between 1992 and 2012. This leads to

.

Under these assumptions for the three scenarios, we obtain . Compared to the example above with a shadow price of

, we now find

, i.e. a change by seven percentage points or by 10% compared to the original shadow price of

. This implies that a 10% subsidy would suffice to correct for the unanticipated developments of future tourism. This crude estimate, however, hinges on our assumptions on parameter values and the relevant time horizon.

5. North–South

This section goes beyond the existing models of tourism in a framework of international trade (see Section 2.1) by introducing a two-country North–South perspective. This perspective is necessary for a welfare analysis which accounts for both suppliers and customers of tourism services. The Appendix details the ‘North’, representing advanced countries which seek ecotourism services in the South. The following subsection deals with the terms-of trade-effects of the scenarios introduced in Section 3 considering strategic behaviour of the South. The next subsection deals with different possibilities for North–South burden-sharing regarding the costs of conserving the natural resource today.

5.1. Terms-of-trade

Let us assume that the relative price for tourism services emerges endogenously from the (optimal) solution and is symbolised by .

determines how much of the industrial good the South can import by exporting tourism services, and vice versa how much tourism services the North can import (or consume within the South) for exporting the industrial good. This relation is well-known as the ‘terms-of-trade’. Two cases exist, in which the terms-of-trade are either taken as given or can be strategically manipulated by the South. Note that the manipulation of the terms-of-trade was consciously ruled out when deriving the socially optimal solution.

Let us focus on the case of monopolistic power, while details of price-taking behaviour can be found in the Appendix. Different to the previous analysis, now reacts endogenously to the depletion of the natural resource,

. This means that the South can manipulate the terms-of-trade in its favour because it controls natural resource consumption,

. This case with monopolistic power characterises unique tourist attractions such as the Krueger National Park or the Galapagos Islands. The welfare effects can be expressed as follows:

These equations resemble those in the Appendix describing price-taking behaviour with one notable difference: above, higher current (first-period) Southern resource consumption,

, reduces the supply of tourism services, increases the costs of producing tourism services owing to scarcity and overexploitation, and drives up the price for the specific tourism service in the international market as reflected by the terms

and

. The resulting terms-of-trade change is in favour of the South and to the detriment of the North.

The possibility for the South to influence the terms-of-trade, however, leads to an outcome which is well-known in trade theory: strategic behaviour of a large open economy that exploits monopolistic power in international markets. Like a monopolist, the large open economy restricts trade volumes and hence raises the price of its export goods relative to the price of its import goods. Typical trade policy measures to achieve this are tariffs and quotas. In the model under scrutiny, the South can simply consume more of the natural resource today to achieve this in the future. Consequently, the strategic behaviour creates an incentive for the South to overexploit the natural resource in addition to incentives created by myopic behaviour. Conversely, the North has an additional incentive to support resource conservation in order to avoid strategic behaviour of the South.

5.2. North–South transfer

This section discusses how forward-looking resource conservation can be achieved such that a win-win situation emerges for the North and the South. The first subsection considers the case, in which a North–South transfer is granted for free. The second subsection considers the case, in which a loan is provided with or without interest. The third subsection discusses other burden sharing options. In any case, the transfer payment finances the optimal subsidy derived in Section 4.1. The underlying welfare analysis builds on the model set-up with monopolistic power discussed in the previous subsection.

5.2.1. Conservation grant

In order to incentivise lower natural resource consumption in the first period, it must hold that the Southern first-period utility gain from higher resource consumption is overcompensated by the following North–South transfer:(4)

denotes the difference between the myopic level of natural resource consumption chosen by the South and the forward-looking socially optimal level,

.Footnote8 To achieve the forward-looking social optimum,

, this transfer needs to be granted in form of the socially optimal subsidy, σ, derived in Section 4.1. The implementation of the optimal subsidy guarantees that there will be a welfare gain resulting from that policy over both periods and within the second period.

The North will be willing to grant this transfer if its total welfare gain from larger volumes of tourism services and corresponding lower prices over both periods exceeds the transfer value. From the point of view of the North, we need to look at , i.e. a reduction of resource consumption induced by the transfer, Θ, to obtain a welfare gain:

If Inequalities (Equation4

(4) ) and (Equation5

) both hold, there will be a win-win situation for the South and the North. Given that the North has overcome obstacles like severe poverty and inequality as well as deep-rooted governance failure, it holds that

so that the North attributes a considerably higher value to the future than the South. This will strengthen the incentive of the North to grant the transfer.

5.2.2. Conservation loan

If the North–South transfer is provided as a loan with or without interest, Inequality (Equation4(4) ) must still hold in order to incentivise Southern resource conservation. In addition, the Southern overall welfare gain from resource conservation must cover the repayment of the transfer plus the interest at the rate i:

As long as Θ is used to implement the optimal subsidy σ and i=0, this condition will be fulfilled. When i>0, it will depend on the level of i. Since the transfer is repayed to the North with interest, the loan-based policy will make the North better off (compared to no policy or the grant-based policy). Thus, if Inequalities (Equation4

(4) ) and (Equation6

) hold, there will be a win-win situation for the South and the North.

5.2.3. Burden sharing

The transfer payment, Θ, can in principle be shared between the South and the North following any sharing rule as long as Inequalities (Equation4(4) ) to (Equation6

) are fulfilled. This means that the industrialised and developing countries involved in the demand or supply of tourism services may agree on any solution in between the grant and the loan solution.

A simple linear sharing rule would define the fraction as a loan to be repaid by the South and the remaining fraction

as a grant to be paid by the North.

will decrease if, for example, more emphasis is put on handicaps of developing countries like poverty, inequality, insufficient infrastructure or technological capability.

will increase if the North has a higher time preference and hence discounts the future at a higher rate.

5.2.4. Numerical example

With respect to burden sharing of the policy costs, the following numbers may shed light on the feasibility of the proposed policy. According to WDI (Citation2014), expenditures by international inbound visitors to low-income countries in 2012 amounted to 17.2 billion US$. This constitutes an upper bound of approximately 0.03% of the total GDP of high-income countries and almost 3% of the total GDP of low-income countries. These shares suggest a low fraction ϕ borne by developing countries, for instance, . Against this backdrop, the financial capability and responsibility of bearing the policy costs mainly rest with industrialised countries.

6. Conclusion

This article has analysed the impact of future (eco)tourism, seeking for unique, non-renewable natural resources, on today's conservation of the natural resources. Such resources are often found in developing countries (South), for example in the tropical zone, and create a comparative advantage. By contrast, developing countries have a comparative disadvantage in industrial production that involves capital accumulation and the creation and application of advanced technologies. The opposite applies to industrialised countries (North) that are abundant in capital and advanced technologies but lack unique natural resources.

The article explicitly derived the shadow price for the natural resource that future tourism creates today so that more of the resource is preserved. In contrast to Mananyi (Citation1998) who derives an optimal tax to preserve wildlife amenities, it was shown that the welfare-maximising policy is a subsidy for resource preservation that mimics this shadow price. The resulting welfare gain can be shared between the South (that provides tourism services) and the North (that demands tourism services) so that the South is better off today and in the future and the North is better off in terms of the sum of welfare today and in the future. This means that forward-looking governments in industrialised countries shall anticipate rising preferences of their population for tourism and preserve natural resources in developing countries, whose population might have myopic short-term attitudes and lack information about future developments. This creates a win-win situation, in which ecotourism can save nature.

This insight contrasts with the pollution-haven hypothesis which posits that globalisation enhances pollution- and resource-intensive production in developing countries with low environmental regulation (e.g. Janicke et al., Citation1997; Levinson & Taylor, Citation2008). It adds a new mechanism to the ‘green growth’ hypothesis in the sense that economic growth is possible while simultaneously preserving the environment (e.g. Smulders, Citation1999; Xepapadeas, Citation2005). The analysis of the underlying economic mechanisms contributes to the literature on terms-of-trade effects of tourism (e.g. Copeland, Citation1991; Chao et al., Citation2006): the overexploitation of the natural resource for the sake of higher consumption today accords with a manipulation of the terms-of-trade in favour of the developing countries because the availability of the resource for providing tourism services in the future will be reduced. This terms-of-trade effect encourages overexploitation of the resource by the developing countries. At the same time, it incentivises financial support for resource conservation by the industrialised countries.

Simple numerical illustrations indicate that a subsidy which modifies relative international prices by about 10% may suffice to correct for the unanticipated future development of tourism. However, considerably stronger policy intervention would be necessary to correct for myopia when a developing country does not attribute any value to future tourism or the future value of its natural resource in general. An option to reduce policy costs, not analysed in this article, is international technology transfer (see e.g. Hübler & Finus, Citation2013, in the climate policy context). Advanced environment-friendly technologies are mostly found in the North and can help the South set up environment-friendly forms of tourism more efficiently than with purely financial support.

The policy strategy discussed in this article is more comprehensive than REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation). It is not restricted to carbon emissions, nor to forests. It includes any valuable natural resource such as unspoilt beaches, coral reefs, natural lakes or savannahs, especially those containing rich and unique biodiversity so that any destruction is irreversible. In this sense, the policy strategy is similar to protected area certification (cf. Dudley, Citation2008, Citation2010; Bushell & Bricker, Citation2017), yet with a broader scope dealing with international nature-seeking tourism. A global fund would be required to preserve the natural resources in developing countries, which could be financed by public and private sources in industrialised (OECD) and emerging countries. Different to climate policy, however, it is not necessary that nearly all (industrialised) countries contribute to the fund. If only specific countries are strongly engaged in nature-seeking international tourism, then mainly these countries will have the obligation to contribute to the fund. This simplifies the establishment of a global treaty compared to the climate policy case. The downside of the suggested support for ecotourism is, however, that CO emissions from aviation and other types of transportation will increase (cf. Forsyth & Dwyer, Citation2014).

Northern tourists and firms in the tourism sector might be willing to contribute to the North–South transfer for guaranteed long-term use of the natural resource for tourism purposes in their own interest. Firms might also buy land in the South to host tourists. Southern firms and smallholders in the ecotourism sector and the domain of public or private nature conservation would directly receive transfers and indirectly benefit from the conserved natural resources that attract tourists. Local communities, local transportation companies, tourist guides, the hotel industry and airlines would be among the beneficiaries. In this way, the North–South transfer will boost the Southern and Northern tourism sector and support people and firms related to it.

Yet, the policy implementation involves serious challenges. In the North, the investment might be too costly, long-lasting and risky for single firms. Hence, a coordinated policy strategy is required that collects funding from many donors/investors. Donor firms or countries need to bargain how the costs of subsidising natural resource preservation shall be distributed among them. Likewise, in the South, ecotourism likely generates additional revenues (cf. Dikgang & Muchapondwa, Citation2017) so that a fair distribution of the revenues among households in the local communities is required (cf. Shoo & Songorwa, Citation2013). As pointed out by Uddhammar (Citation2006), ‘friction between local practices and global conservation norms’ can arise, and ‘governance structures, local ownership and institutions for solving disputes and for joint management’ are important for achieving socio-economic development plus nature conservation (also see Wallace & Russell, Citation2004). Obviously, in the South, the transfers must neither trickle away in intransparent governance structures subject to corruption nor support the informal economy subject to unacceptable working conditions. Furthermore, ecotourism might create significant (marginal) environmental damages and socio-economic problems (cf. Herath, Citation2002) that exceed its (marginal) benefits; in this case, ecotourism subsidies would exacerbate the net social cost. One solution could be international ecotourism certificates (cf. Hara & Iwamoto, Citation2014) with strict social, economic and environmental requirements and monitoring. Furthermore, as usual in the domain of international trade, there are winners and losers within countries. In this case, the tourism sector in the South would benefit from the proposed policy, whereas the sector that exploits natural resources for production (and exports) would be worse off. Social transfers within the South could be used to improve this outcome.

Despite its limitations, this stylised conceptual analysis may open a new avenue for future research. One could first collect more historical data on the volumes and costs of tourism travel as well as expert judgements on their future developments focusing on specific developing countries. Drawing upon the model laid out in this article, one could then set up a computable general equilibrium model and calibrate it to the available data. Once more data on ecotourism are available, these can be used for an econometric analysis of possible environmental and social benefits of ecotourism. Finally, the design and implementation of the proposed policy require further research and discussion.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (274.1 KB)Acknowledgments

I thank two anonymous reviewers and Peter Nunnenkamp, formerly at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Germany, for very helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Cultural and historical resources that attract tourists are not further discussed here.

2 Ecotourism is considered for this analysis because it tries to avoid negative external effects for the environment. Otherwise, the negative effects of tourism for the environment might dominate the positive effects. Nonetheless, this analysis is not restricted to ecotourism in its present form, but takes any form of nature-related, nature-conserving tourism into account.

4 Figure A5 in the Appendix depicts the soaring trend in the number of arrivals of (all) foreign travellers to South Africa. Of these foreign travellers 88% came for holiday reasons (Statistics South Africa, Citation2010/12). A large number of visitors came from high-income, industrialised countries, with the UK, the USA and Germany representing the most important home countries of tourists.

5 Taxing tourism is in general not appropriate in this model framework because we do not explicitly look at a negative environmental externality of tourism (cf. Mananyi, Citation1998; Herath, Citation2002). Instead, we look at nature-conserving ecotourism. Nevertheless, the model allows for the possibility that the net subsidy turns into a net tax on tourism if the negative effects of tourism dominate the positive ones. In this case, σ will become negative.

6 Therefore, it is not applicable to add a fixed ad-valorem subsidy to the market price for tourism services.

7 The equation reflects the value of σ evaluated at the forward-looking optimal solution and

. It is

because

and

, i.e. higher first-period resource consumption lowers second-period possibilities for resource consumption and providing tourism services. It must hold that

according to Equation (15) so that the South does not completely dispense with consuming the resource today.

8 The right-hand side of Inequality (Equation4(4) ) can become negative. Yet, in this case, there will be no intrinsic incentive for the South to choose this consumption level, even under myopic behaviour.

References

- Adams, PD, & Parmenter, BR, 1995. An applied general equilibrium analysis of the economic effects of tourism in a quite small, quite open economy. Applied Economics 27(10), 985–94. doi: 10.1080/00036849500000079

- Antweiler, W, Copeland, BR, & Taylor, MS, 2001. Is free trade good for the environment? American Economic Review 91(4), 877–908. doi: 10.1257/aer.91.4.877

- Beladi, H, Chao, C-C, Hazari, BR, & Laffargue, J-P, 2009. Tourism and the environment. Resource and Energy Economics 31, 39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.reseneeco.2008.10.005

- Bushell, R, & Bricker, K, 2017. Tourism in protected areas: developing meaningful standards. Tourism and Hospitality Research 17(1), 106–20. doi: 10.1177/1467358416636173

- Cerina, F, 2008. Tourism, growth and pollution abatement. In Brau, R, Lanza, A & Usai, S (Eds.), Tourism and sustainable economic development. FEEM, Venice, Italy and Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA, USA, 3–27.

- Chao, C-C, Hazari, BR, Laffargue, J-P, Sgro, PM, & Yu, ESH, 2006. Tourism, Dutch disease and welfare in an open dynamic economy. Japanese Economic Review 57(4), 501–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5876.2006.00400.x

- Chao, C-C, Hazari, BR, Laffargue, J-P, & Yu, ESH, 2009. Is free trade optimal for a small open economy with tourism? In Kamihigashi, T & Zhao, L (Eds.), International trade and economic dynamics, Essays in memory of Koji Shimomura. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 49–62.

- Chateau, J, Rebolledo, C, & Dellink, R, 2011. An economic projection to 2050: the OECD ‘ENV-linkages’ model baseline. OECD Environment Working Papers No. 41, OECD Publishing, Paris, France. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg0ndkjvfhf-en. Accessed June 2017.

- Copeland, BR, 1991. Tourism, welfare and de-industrialization in a small open economy. Economica 58(232), 515–29. doi: 10.2307/2554696

- Copeland, BR, & Taylor, MS, 2003. Trade and the environment: Theory and evidence. Princeton, New Jersey, USA Princeton University Press, and Woodstock, Oxfordshire, UK.

- Dikgang, J, & Muchapondwa, E, 2017. The determination of park fees in support of benefit sharing in Southern Africa. Tourism Economics 23(6), 1165–83. doi: 10.1177/1354816616655254

- Dudley, N, 2008. Guidelines for applying protected area management categories. Gland, Switzerland. IUCN, http://www.wild.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/IUCN-Protected-Area-Catagories.pdf. Accessed June 2017.

- Dudley, N, 2010. An international legal regime for protected areas: protected areas and certification. Gland, Switzerland. IUCN, http://www.cbd.int/doc/pa/tools/Protected%20Areas%20and%20Certification.pdf. Accessed June 2017.

- Dwyer, L, & Forsyth, PJ, 2006. International handbook on the economics of tourism. Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA, USA. Edward Elgar Publishing,

- Forsyth, PJ, & Dwyer, L, 2014. Climate change policies, long haul air travel and tourism. Journal of Tourism Economics, Policy and Hospitality Management 2(1), art. 3.

- Grossman, G, & Krueger, A, 1993. Environmental impacts of a North American free trade agreement. In Garber P (Ed.), The U.S.-Mexico free trade agreement. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 13–56.

- Hara, T, & Iwamoto, H, 2014. Tourism policy analysis on an eco-tour guide certification system at a UNESCO world heritage site: the Shirakami Mountain Range in Japan. Journal of Tourism Economics, Policy and Hospitality Management 2(1), art. 1.

- Hazari, BR, & Sgro, PM, 2004. Tourism, trade and national welfare. Amsterdam, The Netherlands.Elsevier Science and Technology,

- Hazari, BR, & Lin, JJ, 2011. Tourism, terms of trade and welfare to the poor. Theoretical Economics Letters 1, 28–32. doi: 10.4236/tel.2011.12007

- Herath, G, 2002. Research methodologies for planning ecotourism and nature conservation. Tourism Economics 8(1), 77–101. doi: 10.5367/000000002101298007

- Hübler, M, 2015. How tourism can save nature. Hannover Economic Papers (HEP) No. 551. http://diskussionspapiere.wiwi.uni-hannover.de/pdf_bib/dp-551.pdf. Accessed May 2018.

- Hübler, M, & Finus, M, 2013. Is the risk of North-South technology transfer failure an obstacle to a cooperative climate change agreement? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 13(4), 461–79. doi: 10.1007/s10784-013-9208-3

- Jakob, M, Marschinski, R, & Hübler, M, 2013. Between a rock and a hard place: a trade-theory analysis of leakage under production- and consumption-based policies. Environmental and Resource Economics 56(1), 47–72. doi: 10.1007/s10640-013-9638-y

- Janicke, M, Binder, M, & Monch, H, 1997. ‘Dirty industries’: patterns of change in industrial countries. Environmental and Resource Economics 9, 467–91.

- Krstic, B, Jovanovic, S, Jankovic-Milic, V, & Stanisic, T, 2016. Examination of travel and tourism competitiveness contribution to national economy competitiveness of sub-Saharan Africa countries. Development Southern Africa 33(4), 470–85. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2016.1179103

- Kuznets, S, 1955. Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review 45(1), 1–28.

- Levinson, A, & Taylor, MS, 2008. Unmasking the pollution haven effect. International Economic Review 49(1), 223–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2354.2008.00478.x

- Mananyi, A, 1998. Optimal management of ecotourism. Tourism Economics 4(2), 147–69. doi: 10.1177/135481669800400203

- Markusen, JR, 1975. International externalities and optimal tax structures. Journal of International Economics 5, 15–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-1996(75)90025-2

- Markusen, JR, Melvin, JR, Kaempfer, WH, & Maskus, K, 1995. International trade: theory and evidence. New York, USA.McGraw-Hill,

- Matias, Á, Nijkamp, P, & Sarmento, M (Eds.), 2011. Tourism economics. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany.Physika-Verlag/Springer-Verlag,

- Min, W, 2015. How to construct system guarantee for economic development of eco-tourism resources based on value compensation. The Anthropologist 22(1), 101–12. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2015.11891861

- Muzvidziwa, VN, 2013. Eco-tourism, conservancies and sustainable development: the case of Zimbabwe. Journal of Human Ecology 43(1), 41–50. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2013.11906610

- Nowak, J-J, Sahli, M, & Sgro, PM, 2003. Tourism, trade and domestic welfare. Pacific Economic Review8(3), 245–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0106.2003.00225.x

- OECD, 2008. Environmental outlook to 2030. Paris, France.OECD Publishing,

- Ollivier, H, 2012. Growth, deforestation and the efficiency of the REDD mechanism. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 64(3), 312–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2012.07.007

- PMG, 2012. South African National Parks on tourism development, growth, transformation, tariff increases. Parliamentary Monitoring Group, South Africa. http://www.pmg.org.za/report/20120821-south-african-national-parks-tourism-development-growth-transformatio. Accessed June 2017.

- Rogerson, CM, 2007. Reviewing Africa in the global tourism economy. Development Southern Africa 22(3), 361–79. doi: 10.1080/03768350701445350

- Shoo, RA, & Songorwa, AN, 2013. Contribution of eco-tourism to nature conservation and improvement of livelihoods around Amani nature reserve, Tanzania. Journal of Ecotourism 12(2), 75–89. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2013.818679

- Smulders, S, 1999. Endogenous growth theory and the environment. In van den Bergh J (Ed.), Handbook of environmental and resource economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA, USA, 610–21.

- Snyman, S, 2017. The role of private sector ecotourism in local socio-economic development in southern Africa. Journal of Ecotourism 16(3), 247–68. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2016.1226318

- Stabler, MJ, Papatheodorou, A, & Sinclair, MT, 2010. The economics of tourism, 2nd ed. Oxon, UK, and New York, USA.Routledge (Taylor and Francis),

- Statistics South Africa, 2010/12. Tourism, 2010/12. South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-51-02/Report-03-51-022010.pdf, http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-51-02/Report-03-51-022012.pdf. Accessed June 2017.

- Stern, DI, 2004. The rise and fall of the environmental Kuznets curve. World Development 32(8), 1419–39. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.03.004

- Tisdell, CA, 2001. Tourism economics, the environment and development: analysis and policy. Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA, USA.Edward Elgar Publishing,

- Uddhammar, E, 2006. Development, conservation and tourism: conflict or symbiosis?. Review of International Political Economy 13(4), 656–78. doi: 10.1080/09692290600839923

- Wallace, G, & Russell, A, 2004. Eco-cultural tourism as a means for the sustainable development of culturally marginal and environmentally sensitive regions. Tourist Studies 4(3), 235–54. doi: 10.1177/1468797604057326

- WDI, 2014. World development indicators. The World Bank, Washington, D.C. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. Accessed June 2017.

- Xepapadeas, A, 2005. Economic growth and the environment. In Mäler K-G & Vincent JR (Eds.), Handbook of environmental economics 3. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1219–71.