ABSTRACT

Human–wildlife interaction in Boteti district, Botswana is critical. Wild animals destroy agricultural products and threaten human lives. This paper, therefore, assesses the economic effects of wildlife crop raiding on the livelihoods of arable farmers in Khumaga, Boteti sub-district, Botswana. A total of 119 arable farmers were interviewed using open and closed-ended structured questionnaires in this study. Key informant interviews were also conducted through purposive selection. Findings indicate that wild animals destroy agricultural production at Khumaga leading to food insecurity; sometimes farmers can lose the entire field in single elephant crop raiding. The elephant (Loxodonta africana) was reported by respondents to be a problem animal. In conclusion, decision-makers should ensure that farmers at Khumaga are protected and inducted with mitigation strategies that are effective against wildlife to improve arable farmer’s livelihoods and conservation efforts at Khumaga village and in Botswana.

1. Introduction

Human–wildlife conflict (HWC) in agro-ecosystems is a challenge to wildlife management and conservation throughout the world (Ogra, Citation2009; Hill & Wallace, Citation2012; Barua et al., Citation2013; Gupta, Citation2013; Mc Guinness & Taylor, Citation2014). Negative consequences of HWC include the destruction of food and livestock, and the consequent loss of income, livelihoods and sense of wellbeing. (Hoare, Citation2000; Hill, Citation2004; Linkie et al., Citation2007; Karanth et al., Citation2013; Mc Guinness & Taylor, Citation2014).

In recent years one of the most serious concerns in food production across sub-Saharan Africa has been crop loss due to wildlife crop raiding, more specifically elephants raiding (O’Connell-Rodwell et al., Citation2000; Osborn, Citation2004; Fairet, Citation2012). Crop raiding threatens local agricultural practices and rural food supply and undermines conservation efforts (Osborn & Parker, Citation2002; Hartter, Citation2009). Kansky et al. (Citation2014) claim that sometimes the loss caused by wildlife may seem insignificant at a national level but it is a high cost for the affected individuals and families, many of whom are amongst the least privileged people in the world.

Some scholars (Irigia, Citation1990; Thouless & Tchamba, Citation1992) have estimated crop damage by elephants in monetary terms in Northern Cameroon and in Western Laikipia, Kenya. No comparable information is available for Botswana. Studies by Adams & Hutton (Citation2007) and (Treves, Citation2007) found that the resultant losses often arouse negative perceptions against wildlife, such that people are unlikely to support conservation. These losses sometimes lead to retaliatory attacks on animals, some of which are protected by international instruments.

Scholars (Mulder, Citation2006; Dickman, Citation2010) suggest that reducing wildlife damage alone will fail to produce long-term conflict resolution. It is therefore advisable to carry out a survey to determine how communities want the HWC situation to be addressed (Weladji & Tchamba, Citation2003)

In Botswana, particularly in Ngamiland, Okavango, Chobe enclave and Boteti areas, the issue of wildlife crop raiding is critical (Mosojane, Citation2004; DEA, Citation2010; Sifuna, Citation2010; Gupta, Citation2013). There have been several complaints from the people of Khumaga at Boteti sub-district on the issue of problem animals destroying crops and the property of farmers (DEA, Citation2010). The people of Khumaga are small-scale farmers who entirely depend on subsistence agriculture for their livelihoods but the crops they grow are destroyed by wildlife, leading to food insecurity.

Economic losses of the local people due to crop damage is one of the major issues that triggers HWC and causes problems in achieving long-term conservation in the area (DEA, Citation2010). This is likely to cause the affected community to develop negative attitude towards wildlife conservation as they are vulnerable to the effects of wildlife crop raiding (Nyirenda et al., Citation2012). The main focus of this paper is therefore to address the question: what are the economic effects of wildlife crop raiding on the livelihoods of arable farmers in Khumaga, Boteti sub-district, Botswana.

2. Study area

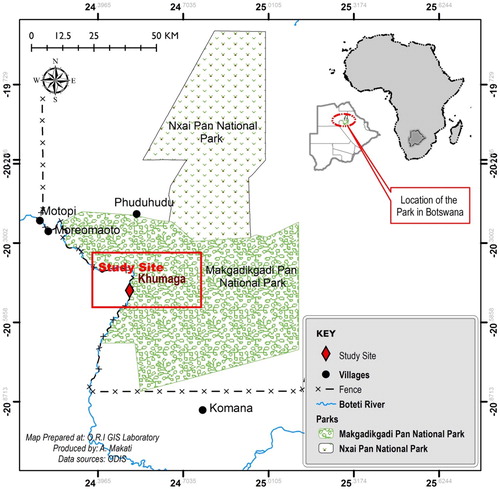

This study was carried out at Khumaga village, which is located in Boteti, in the Central district of Botswana (). The Boteti area is situated in north-central Botswana, a sparsely populated, semi-arid country located in Southern Africa. Boteti has a population of approximately 57 376 people (CSO, Citation2011) and a mean annual rainfall of approximately 350 mm (Ringrose et al., Citation1996). The dominant form of land tenure is communal, although private leasehold livestock ranching is emerging, and state land in the form of game reserves also exists (Ringrose et al., Citation1996). Subsistence agro-pastoralism is the dominant livelihood source, but sources of income include formal and informal employment, and livestock sales (Ringrose et al., Citation1996; DEA, Citation2010). The Boteti river is the only permanent source of water available to wildlife, concentrated just north of Khumaga (Hemson, Citation2004).

Figure 1. Map of the study area showing Khumaga. Map prepared at: Okavango Research Institute (ORI), GIS Laboratory.

The study was narrowed down to Khumaga village. The population of this village is 758 (CSO, Citation2011). The village is on the western side of Makgadikgadi Pan National Park near the Boteti river. Khumaga village is a classic case study because HWC is higher in this area, possibly due to its close proximity to Makgadikgadi Pan National Park (Hemson, Citation2004). This national park’s biological wealth consists of indigenous trees like baobabs and palm trees, large populations of migratory ungulates and predators, and non-migratory animals, birds and reptiles (Valeix et al., Citation2012). The park was established in the 1970s and is surrounded by dense human populations and increasingly degraded subsistence farming land (DEA, Citation2010).

Large animals found in the area include, among others, elephant (Loxodonta africana), gemsbok (Oryx gazella), giraffe (Girraffa camelopardelis), kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus), ostrich (Struthio camelus) and hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius) (DWNP, Citation2014). The carnivores found in the area include lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panthera pardus), brown hyena (Hyaena brunnea), wild dog (Lycaon pictus) and jackal (Canis mesomelas) (Hemson, Citation2004; DWNP, Citation2014).

Khumaga residents share the Boteti river with wildlife (DEA, Citation2010). The river that is used to separate the park from the neighbouring village dried up in the mid-1980s and began to flow again in 2009. Several farm and non-farm economic activities are sources of livelihoods for people living in Khumaga. Farm-based activities include livestock farming, dry land arable farming, molapo or flood recession cultivation and small-scale gardening. Farming is undertaken mostly for subsistence purposes. The major ethnic groups at Khumaga village are Banajwa and Bayei.

3. Methods

3.1 Types of data collected and techniques used

Collection of data for this study was done between January and March 2015. Primary and secondary data sources were used to collect both qualitative and quantitative data. Face-to-face interviews were the main tool used to collect primary data with arable farmers, using open and closed-ended questions; the closed-ended questions had a list of alternative answers to each question. All interviews were conducted in Setswana, which is a national language spoken and understood throughout Botswana.

Indicators used to measure the effects of wildlife crop raiding on livelihoods include but are not limited to: livelihood activities of respondents, types of crops planted, hectares ploughed, hectares destroyed by wildlife, accumulated hectares, expected yield and actual yield per crop per year, and loss per crop in monetary terms per year using Botswana Agricultural Marketing Board (BAMB) rates. Interview data from respondents and key informants were summarised to identify patterns in the effects of wildlife crop raiding on the livelihoods of arable farmers in Khumaga. In-depth interviews were also conducted with key informants to establish the effects of the wildlife crop raiding. Key informants included: Department of Crop Production, Department of Wildlife and National Parks, community leaders (including village chief/headman). Key informants are able to provide more information and a deeper insight into what is going on around them as a result of their personal skills, or position within a society (Marshall, Citation1996).

In-depth interviews with key informants took advantage of their experience and long-term knowledge of livelihood changes in their respective villages over time. The interviews with these key informants also took advantage of their experience in arable farming at Khumaga and their long-term knowledge of human–wildlife interaction. General observations of damage caused by wildlife were also made during the visits to farmers. Even though an open-ended questionnaire was used, interviews progressed in a discussion style.

The main purpose of the questionnaire was to guide discussion during the interview and keep it focused. This method was ideal as free-response questions could be asked to dig deeper about a particular issue (Mbaiwa, Citation2011). In addition a recording device was used to record all the face-to-face household and key informants’ interviews. The recording of interviews was done to capture in detail all the data from respondents, especially that from open-ended questions.

3.2 Sampling design

A sampling frame consisting of 120 active arable farmers from Khumaga village was sourced from the Department of Crop Production in Khumaga. The sampling unit was an active arable farm. Active arable farmers in this study refers to arable farmers who have been ploughing for the past five years continuously up to the time of data collection. The list of active arable farmers was provided by the agricultural demonstrator of Khumaga. In order to collect data on crop raiding, 119 arable farmers were interviewed from the total sample of 120 active arable farmers in Khumaga. The intention was to do a total census but one farmer refused the interview. The results of this study are more precise as the researcher interviewed all active arable farmers, except only one that refused the interview. According to Walton-Roberts et al. (Citation2014), census data are vital for small area assessments. Conducting a census often results in enough respondents to have a high degree of statistical confidence in the survey results. Key informants were also purposively sampled.

3.3 Data management and analysis

Data collected in this study were coded and entered into a Statistical Package for Social Sciences database. Thereafter, data were cleaned in preparation for analysis. Borg & Gall (Citation1989) observed that data analysis involves the rearrangement and manipulation of raw datasets so that they yield the information they hold in as clear a manner as possible. Descriptive analyses were carried out; the information was then used to create a contingency table, which displays the frequency of each of the variables. The mean, median and standard deviation for the data were calculated.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Challenges faced by arable farmers

Crop raiding and environmental conditions make farming difficult and often relatively unproductive at Khumaga village. Interviews with arable farmers at Khumaga indicate that farming is more affected by wildlife crop raiding than other factors. This was indicated by 97% of respondents who strongly agreed that wildlife crop raiding is a challenge to arable farming at Khumaga; 84% agreed that low rainfall is also a challenge to crop production and 60% of respondents disagreed that shortage of machinery is a challenge ().

Table 1. Challenges faced by farmers at Khumaga.

The reason why machinery is not a problem at Khumaga is because of Integrated Support Programme for Arable Agriculture Development (ISPAAD). ISPAAD was introduced in 2008 by the government of Botswana to address challenges facing the country’s arable farmers. The components of ISPAAD include, among others, provision of draught power for arable farmers, portable water and seeds. Subsistence farmers are assisted with 100% subsidy for hybrid seeds to cover a maximum of 5 hectares and open pollinated seeds to cover a maximum of 16 hectares.

The agricultural demonstrator at Khumaga reported wildlife crop raiding, unreliable rainfall and pests including birds to be a problem for crop production. He further said that wildlife, especially elephants, are the most challenging factor as most of his farmers use thorn bush around their fields to protect crops. This concurs with findings of Warner (Citation2008), who observed that despite unpredictable environmental conditions that are beyond farmers’ control, farmers often point to elephant depredation as one of the greatest challenges they face in crop production. Weladji & Tchamba (Citation2003) also found that crop damage affected 86% of households in six months in the Bénoué Wildlife Conservation Area of North Cameroon.

4.2 Crop raiding in the last five years and animals liable for the damage

In order to understand the effects of crop raiding over a period of time, farmers were asked to state whether they had experienced crop raiding in the last five years. Results from the farmers’ interviews indicate that a total of about 85% of respondents had experienced wildlife crop raiding in the last five years (). This suggests that wildlife crop raiding at Khumaga was found to be very high.

Table 2. Number of years that farmers experienced wildlife crop raiding from 2010–14.

Respondents were asked to name the crop raiders in their area. Elephant (Loxodonta africana), hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius), porcupine (Hystrix africaeaustralis), monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops), duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia), jackal (Canis mesomelas) and kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) were reported to raid crops at Khumaga. Respondents (100%, n = 119) ranked the elephant as the most frequent crop raider and the jackal was ranked second with 72% (n = 86) (). Other studies (e.g. Darkoh & Mbaiwa, Citation2005) in the region found that elephant (Loxodonta africana), antelopes such as kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) and hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius) are responsible for crop damage.

Table 3. Ranking of problem animals involved in crop raiding.

Gillingham & Lee (Citation2003) also reported that over 95% of people living next to the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania perceived crop damage from wildlife to be a limiting factor of crop yields. It is not surprising that 85% of arable farmers experienced wildlife crop raiding due to elephants. Several studies examining problem elephants and their crop raiding behaviour have drawn similar conclusions: that elephants consume cultivated crops because of spatial constraints and because they seek the nutrients provided by those crops (Osborn, Citation2004; Codron et al., Citation2006; Rode et al., Citation2006).

Elephants have a high population (10 697 elephants) compared to other crop raiders in the central district (DWNP, Citation2012); Makgadikgadi Pan National Park has about 740 elephants (Chase, Citation2011). As a result, it is not surprising that they cause the highest depredation compared to other animals. However, Naughton-Treves (Citation1998) claims that local communities sometimes complain most about elephants on the basis that they can destroy an entire field in one night, not that they are the most frequent problem animal.

There are other wild animals that can also cause a great deal of crop damage but because they are not as physically imposing as elephants, farmers can easily chase them away and they do not cause as much damage in a single raiding incident. Farmers may perceive them as less destructive than elephants (Naughton-Treves, Citation1998; Warner, Citation2008). Campbell-Smith et al. (Citation2010) state that the potential dangers posed by conflicts with large-bodied species may also negatively influence the local attitude compared to attitudes towards small-bodied animals.

The crops that were commonly grown at Khumaga included millet, maize, sorghum, watermelon, beans and sweet reeds. Some studies have shown that these crops are prone to crop raids (Gillingham & Lee, Citation2003; Chiyo et al., Citation2005). According to Chiyo et al. Citation(2005), crop quality tends to attract elephants more than wild food. This is supported by this study as crop raiding by elephants usually happens when wild crops are also available. In their study in Uganda, Rode et al. (Citation2006) found that the reason why elephants raid crops even though wild plants are available is because crops have low secondary compounds and contain high sodium levels, which is an important nutrient for elephants.

It was noted by arable farmers in Khumaga that: elephants (Loxodonta africana) and hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius) raid all ploughed crops; monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) feed on maize, sweet reeds and watermelon; jackals (Canis mesomelas) feed on watermelon; porcupines (Hystrix africaeaustralis) feed on maize and watermelon; kudus (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) and duikers (Sylvicapra grimmia) feed on beans.

4.3 Amount of crop losses to animals

The measurement of actual crop losses is difficult and controversial (Hill, Citation2002). In relation to crop production and loss due to wildlife crop raiding, costs incurred by arable farmers at Khumaga were assessed by asking respondents how many hectares were ploughed and how many hectares were destroyed each year (). Results indicate that, for the year 2014, 356.5 hectares were ploughed by respondents in total, and 342.5 hectares or 96.1% were destroyed.

Table 4. Hectares ploughed and destroyed.

Crop damage by wildlife also affects the yield for each farmer. Results in show the number of bags expected by farmers for the years 2010 to 2014. Farmers expected a total of 2824.5 bags of millet and 2954.5 bags of maize ().

Table 5. Expected yield per crop each year.

Results in show losses suffered by arable farmers due to wildlife crop raiding, from 2010 to 2014. The greater loss was incurred by farmers in each crop they ploughed. The loss for millet from 2010 to 2014 was 2603 bags or 92.2% ().

Table 6. Loss per crop each year.

These results in –6 show that arable farmers of Khumaga experience persistent wildlife crop raiding that seriously affects their livelihoods. One of the respondents sceptically remarked, ‘We are given seeds and machinery for free by government to plough for her elephants’ when referring to the damage caused by elephants.

In western Laikipia, Kenya, Irigia (Citation1990) recorded damage of between 10% and 24% of the total maize crop. At Lake Mburo National Park, Uganda, animals were reported to also destroy 85% of the crops planted (Kagoro-Rugunda, Citation2004). Thouless (Citation1994) counted crop depredation of maize (45%), followed by beans (13%), wheat (11%), potatoes (5%) and bananas (5%) at Kenya.

shows the condition of wildlife crop raiding at Khumaga over three consecutive days, a day before crop raiding and a day after crop raiding by elephants. Naughton-Treves (Citation1998) contends that elephant raiding can cause entire farms to be abandoned.

4.4 Monetary loss due to crop damage by wildlife

The losses reported by farmers were calculated in monetary terms. As a result, findings in this study indicate that, from 2010 to 2014, farmers lost bags of millet worth P542 829.70 (US$55 041.09) or 92.2% of the expected value (). Based on assumptions from BAMB, the rate for millet per 50 kg is P208.54, maize P150.60 per 50 kg, sorghum P177.30 per 50 kg, beans P700.00 per 50 kg, and groundnuts P643.50 per 50 kg. These results indicate that farmers at Khumaga lost lots of Pula’s worth of crops.

Table 7. Loss per crop in monetary terms per year.

Human–elephant interaction is exclusively negative and includes financial losses as a result of crop raiding. Communities near a protected area boundary suffer a disproportionate amount of damage (Naughton et al., Citation1999; Mosojane Citation2004). Barua et al. (Citation2013) and Kansky et al. (Citation2014) indicate that sometimes the loss caused by wildlife may seem insignificant at a national level but has a high cost for the affected individuals and families, many of whom are amongst the least privileged people in the world. Thouless & Tchamba (Citation1992) also estimated crop damage by elephants in Northern Cameroon to be more than US$200 000, while Irigia (Citation1990) assessed the crop damage in Ol Ari Nyiro Ranch in Western Laikipia, Kenya to be more than US$33 000.

5. Conclusion

The study set out to assess the economic effects of wildlife crop raiding on the livelihoods of the Khumaga community. Though Botswana’s tourism is based on wildlife and wilderness, which needs to be conserved, arable farmers incur costs from wildlife. Results of this study have shown that wildlife crop raiding is one of the contributing factors of poverty in Khumaga village; farmers lose food and a lot of income that could be attained from arable farming each season to crop raiders. In some instances, farmers lose a whole field, particularly to elephants, which inflict heavy losses. Nchanji & Lawson Citation(1998) reported that crop raiding is a serious problem to arable farmers as crop raiding animals can have a devastating impact on the standard of living of farmers whose entire survival is dependent on subsistence agriculture. The majority of arable farmers at Khumaga indicated that they have abandoned molapo farming due to the high incident of wildlife crop raiding.

Elephants are reported to be the most destructive animals in Khumaga. Therefore, decision-makers should ensure that farmers at Khumaga are protected and inducted with mitigation strategies that are effective against wildlife to improve arable farmers’ livelihoods and conservation efforts in Khumaga village. Patrols by Department of Wildlife and National Parks officers are an essential requirement in Khumaga. Innovative methods, such as the use of electric fences and bee hives to keep animals away from farmers’ fields, can help in mitigating HWC in the area. Other strategies, such as early warning systems, thunder flashes, chilli borms, community scouts and a combination of repellents, are reported by some authors to be effective in reducing wildlife crop raiding (O’Connell-Rodwell et al., Citation2000; Sitati et al., Citation2005).

Acknowledgements

A portion of this work (abstract) was presented at the Tropentag Conference on ‘Solidarity in a competing world fair use of resources’, September 18–21, 2016, Vienna, Austria.

We would like to express our gratitude to the people of Khumaga and government officials for providing us with information used in this study. We also wish to express our gratitude to the Southern African Science Service Centre for Climate Change and Adaptive Land Management Project for funding the study. Finally, we wish to thank our colleagues (ORI staff) for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Olekae Tsompi Thakadu http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3903-4198

Reference

- Adams, WM & Hutton, J, 2007. People, parks and poverty: political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conservation and society 5(2), 147–83.

- Barua, M, Bhagwat, SA & Jadhav, S, 2013. The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biological Conservation 157, 309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.014

- Borg, W & Gall, M, 1989. The methods and tools of observational research. In Borg, W & Gall, M (Eds.), Educational research: an introduction. 4th edn. Longman, London. pp. 473–530.

- Campbell-Smith, G, Simanjorang, HV, Leader-Williams, N & Linkie, M, 2010. Local attitudes and perceptions toward crop-raiding by orangutans (Pongo abelii) and other nonhuman primates in northern Sumatra, Indonesia. American Journal of Primatology 72(10), 866–76. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20822

- Chase, M, 2011. Dry season fixed-wing aerial survey of elephants and wildlife in northern Botswana, September-November 2010. Elephants Without Borders, the Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Botswana and the Zoological Society of San Diego, Kasane.

- Chiyo, PI, Cochrane, EP, Naughton, L & Basuta, GI, 2005. Temporal patterns of crop raiding by elephants: a response to changes in forage quality or crop availability? African Journal of Ecology 43(1), 48–55.

- Codron, J, Lee-Thorp, JA, Sponheimer, M, Codron, D, Grant, RC & de Ruiter, DJ, 2006. Elephant (Loxodonta africana) diets in Kruger National Park, South Africa: spatial and landscape differences. Journal of Mammalogy 87(1), 27–34. doi: 10.1644/05-MAMM-A-017R1.1

- CSO, 2011. Population and housing census, 2011. Statistics Botswana, Gaborone.

- Darkoh, M & Mbaiwa, J, 2005. Natural resource utilization and land use conflicts in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Department of Environmental Science and Harry Oppenheimer Okavango Research Centre, University of Botswana.

- DEA, 2010. The Makgadikgadi framework management plan. Volume 2. Technical reports. Department of Environmental Affairs, Gaborone.

- Dickman, A, 2010. Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife conflict. Animal Conservation 13(5), 458–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x

- DWNP, 2012. Community support & outreach division annual report Gaborone.

- DWNP, 2014. Department of wildlife and national park; Problem animal Control Unit. Gaborone.

- Fairet, EMM, 2012. Vulnerability to crop-raiding: an interdisciplinary investigation in Loango National Park. Doctoral dissertation, Ph. D. thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK.

- Gillingham, S & Lee, PC, 2003. People and protected areas: a study of local perceptions of wildlife crop-damage conflict in an area bordering the Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania. Oryx 37(03), 316–25. doi: 10.1017/S0030605303000577

- Gupta, AC, 2013. Elephants, safety nets and agrarian culture: understanding human-wildlife conflict and rural livelihoods around Chobe National Park, Botswana. Journal of Political Ecology 20, 238–54. doi: 10.2458/v20i1.21766

- Hartter, J, 2009. Attitudes of rural communities toward wetlands and forest fragments around Kibale National Park, Uganda. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 14(6), 433–47. doi: 10.1080/10871200902911834

- Hemson, GA, 2004. The ecology of conservation of lions: Human wildlife conflict in semi-arid Botswana. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford.

- Hill, CM, 2002. Primate conservation and local communities—ethical issues and debates. American Anthropologist 104(4), 1184–94. doi: 10.1525/aa.2002.104.4.1184

- Hill, CM, 2004. Farmers’ perspectives of conflict at the wildlife–agriculture boundary: some lessons learned from African subsistence farmers. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 9(4), 279–86. doi: 10.1080/10871200490505710

- Hill, CM & Wallace, GE, 2012. Crop protection and conflict mitigation: reducing the costs of living alongside non-human primates. Biodiversity and Conservation 21(10), 2569–87. doi: 10.1007/s10531-012-0318-y

- Hoare, R, 2000. African elephants and humans in conflict: the outlook for co-existence. Oryx 34(01), 34–8. doi: 10.1017/S0030605300030878

- Irigia, B, 1990. Elephant crop raiding assessment in Ngarua Division of Laikipia District. Unpublished report to the Kenya Wildlife Service.

- Kagoro-Rugunda, G, 2004. Crop raiding around Lake Mburo National Park, Uganda. African Journal of Ecology 42(1), 32–41. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-6707.2004.00444.x

- Kansky, R, Kidd, M & Knight, AT, 2014. Meta-analysis of attitudes toward damage-causing mammalian wildlife. Conservation Biology 28(4), 924–38.

- Karanth, K, Naughton-Treves, L, DeFries, R & Gopalaswamy, A, 2013. Living with wildlife and mitigating conflicts around three Indian protected areas. Environmental Management 52(6), 1320–32. doi: 10.1007/s00267-013-0162-1

- Linkie, M, Dinata, Y, Nofrianto, A & Leader-Williams, N, 2007. Patterns and perceptions of wildlife crop raiding in and around Kerinci Seblat National Park, Sumatra. Animal Conservation 10(1), 127–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00083.x

- Marshall, MN, 1996. The key informant technique. Family Practice 13(1), 92–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.1.92

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2011. Changes on traditional livelihood activities and lifestyles caused by tourism development in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Tourism Management 32(5), 1050–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.002

- Mc Guinness, S & Taylor, D, 2014. Farmers’ perceptions and actions to decrease crop raiding by forest-dwelling primates around a Rwandan forest fragment. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 19(2), 179–90. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2014.853330

- Mosojane, S, 2004. Human-Elephant conflict in the eastern Okavango panhandle. MSc Thesis, University of Pretoria.

- Mulder, MB, 2006. Conflict and coexistence: Elsevier current trends.

- Naughton, L, Rose, R & Treves, A, 1999. The social dimensions of human-elephant conflict in Africa: a literature review and case studies from Uganda and Cameroon. A report to the African Elephant Specialist Group, Human-Elephant Conflict Task Force, IUCN, Glands, Switzerland.

- Naughton-Treves, L, 1998. Predicting patterns of crop damage by wildlife around Kibale National Park, Uganda. Conservation Biology 12(1), 156–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.96346.x

- Nchanji, AC & Lawson, DP, 1998. A survey of elephant crop damage around the Banyang-Mbo Wildlife Sanctuary, 1993–1996. Unpublished report to Cameroon Biodiversity Project and The Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx, New York.

- Nyirenda, VR, Myburgh, WJ & Reilly, BK, 2012. Predicting environmental factors influencing crop raiding by African elephants (Loxodonta africana) in the Luangwa Valley, eastern Zambia. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 6(10), 391–400. doi: 10.5897/AJEST11.180

- O’Connell-Rodwell, CE, Rodwell, T, Rice, M & Hart, LA, 2000. Living with the modern conservation paradigm: can agricultural communities co-exist with elephants? A five-year case study in East Caprivi, Namibia. Biological Conservation 93(3), 381–91. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00108-1

- Ogra, M, 2009. Attitudes toward resolution of human–wildlife conflict among forest-dependent agriculturalists near Rajaji National Park, India. Human Ecology 37(2), 161–77. doi: 10.1007/s10745-009-9222-9

- Osborn, F, 2004. Seasonal variation of feeding patterns and food selection by crop-raiding elephants in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Ecology 42(4), 322–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2028.2004.00531.x

- Osborn, FV & Parker, GE, 2002. Community-based methods to reduce crop loss to elephants: experiments in the communal lands of Zimbabwe. Pachyderm 33, 32–8.

- Ringrose, S, Chanda, R, Nkambwe, M & Sefe, F, 1996. Environmental change in the mid-Boteti area of north-central Botswana: biophysical processes and human perceptions. Environmental Management 20(3), 397–410. doi: 10.1007/BF01203847

- Rode, KD, Chiyo, PI, Chapman, CA & McDowell, LR, 2006. Nutritional ecology of elephants in Kibale National Park, Uganda, and its relationship with crop-raiding behaviour. Journal of Tropical Ecology 22(04), 441–49. doi: 10.1017/S0266467406003233

- Sifuna, N, 2010. Wildlife damage and its impact on public attitudes towards conservation: a comparative study of Kenya and Botswana, with particular reference to Kenya’s Laikipia region and Botswana’s Okavango delta region. Journal of Asian and African Studies 45(3), 274–96. doi: 10.1177/0021909610364776

- Sitati, NW, Walpole, MJ & Leader‐Williams, N, 2005. Factors affecting susceptibility of farms to crop raiding by African elephants: using a predictive model to mitigate conflict. Journal of Applied Ecology 42(6), 1175–82.

- Thouless, C & Tchamba, M, 1992. Emergency evaluation of crop raiding elephants in Northern Cameroon. Report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Thouless, CR, 1994. Conflict between humans and elephants on private land in northern Kenya. Oryx 28(02), 119–27. doi: 10.1017/S0030605300028428

- Treves, A, 2007. Balancing the needs of people and wildlife: when wildlife damage crops and prey on livestock. Tenure Br 7, 1–10.

- Valeix, M, Hemson, G, Loveridge, AJ, Mills, G & Macdonald, DW, 2012. Behavioural adjustments of a large carnivore to access secondary prey in a human-dominated landscape. Journal of Applied Ecology 49(1), 73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02099.x

- Walton-Roberts, M, Beaujot, R, Hiebert, D, McDaniel, S, Rose, D & Wright, R, 2014. Why do we still need a census? Views from the age of ‘truthiness’ and the ‘death of evidence’. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 58(1), 34–47. doi: 10.1111/cag.12065

- Warner, MZ, 2008. Examining human–elephant conflict in southern Africa: causes and options for coexistence.

- Weladji, RB & Tchamba, MN, 2003. Conflict between people and protected areas within the Bénoué wildlife conservation area, North Cameroon. Oryx 37(01), 72–9. doi: 10.1017/S0030605303000140