ABSTRACT

This article explores the city-campus dynamic in East London’s inner city in the light of international experiences and investigates the place-based opportunities for higher education institutions to play a more instrumental role in shaping the economic development and the urban built environment in this struggling former industrial city. At a wider national level, the article is intended as a case study that will allow scholars and planners to reflect on whether South Africa’s higher education and city planning policy frameworks and approaches are designed to respond effectively to recent economic change in cities and regions and are positively aligned with local place-based development challenges. The article highlights the potential for the use of both anchor and innovation district strategies in the city, but does not prescribe a particular model or solution.

1. Introduction

Universities based in cities have become major players in the economy and planning of those cities. According to Campell et al. (Citation2005), they have become drivers of the urban economy and growth. In other words, universities and other higher education institutions (HEIs) are the new anchors of development that steer the growth processes of the city and the region. However, the city of East London, which is now part of the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality in the Eastern Cape in South Africa, has never had its own university. This has had a negative impact on the growth and development of the city because HEIs, especially universities, have been anchors of development in many successful cities. The satellite campuses of various universities within the city of East London have done little towards improving the place where they are located. The major question is whether these satellite’s lack of contribution to place-making can be attributed to their self-interest or the city’s unresponsive attitude. This article argues that the city of East London is endowed with many HEIs that can, and should, anchor the development of the city, which has been experiencing both economic and infrastructural decline.

In 1927, the East London Technical College was established on the edge of the central business district (CBD) next to the city’s two most prestigious public schools, Clarendon High School for Girls and the boys-only Selborne College. The technical college offered a range of mainly part-time professional, technical and arts and crafts courses to city residents. It was the only HEI in East London until the mid-1980s, when the city council and the business chamber persuaded Rhodes University to set up a satellite campus in the city. One of the reasons that East London was never able to establish its own city university, as the neighbouring motor city of Port Elizabeth did in the mid-1960s, was because it became wedged between the two apartheid ‘homelands’ (Ciskei and Transkei), which were both promised their own universities by the apartheid government in the 1960s. Indeed, by the late 1970s, the Eastern Cape region had created universities for all its racial and ethnic groupings – Rhodes University in Grahamstown for white, English speakers; the University of Port Elizabeth for white Afrikaners and English speakers; the historical mission college of the University of Fort Hare (UFH) in Alice mainly for black Xhosa speakers from the Ciskei; and the new University of the Transkei for black Xhosa speakers from the Transkei. The organisation and focus of HE in the region at that time was thus fundamentally shaped by the political imperatives of apartheid, rather than by the region’s educational and economic needs (see Bank & Qebeyi, Citation2017; Bank, Citation2018).

In the early 1960s, middle-class residents in East London had argued that the city should be given a university of its own, especially after its rapid economic and demographic growth after the Second World War. In the 1950s, East London was one of the fastest-growing industrial centres in South Africa, outstripping the southern Transvaal between 1950 and 1954 (cf. Houghton, Citation1960: 212; Bank, Citation2018). Some argued that a university would help the city and region sustain its economic growth; others argued that all maturing urban centres required university-level institutions of higher learning. The call for more HEIs fell on deaf ears because the apartheid plan was already being developed in the region. For three decades, the city suffered economically as a result of not having a university and then, finally, when the performance of the city economy reached an all-time low in the 1980s, the city chamber of business begged the city to try to persuade Rhodes University to come to its rescue. Rhodes somewhat reluctantly agreed and, by the end of the 1990s, there were 2000 students studying for degrees with Rhodes in the city. The campus developed primarily in response to the needs of the business community, which supported it, and focused mainly on subjects such as law, business management, accounting, economics and basic primary education. Most of the students in this first phase of the campus’s development were part time and had day jobs in the city and its surrounding areas (Bank, Citation2018).

This changed fundamentally after 2000, when the HE landscape in South Africa and the region was reviewed and restructured. The University of Port Elizabeth became the new Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University as a result of the merger of several HEIs in that city. But, in East London, Rhodes was stripped of its East London campus, while both UFH and the Walter Sisulu University (WSU) – a comprehensive university that included the former University of the Transkei and the former Border Technikon – acquired city campuses there. Fort Hare took over Rhodes’s East London facility in its entirety, while WSU absorbed the old technical college and also acquired new buildings for expansion in the CBD. By 2004, when the merger process was complete, the inner city was cluttered with satellite campuses. In addition to the new faculties and buildings associated with Walter Sisulu and Fort Hare, a small branch campus of the University of South Africa (UNISA) was also set up in the inner city, while the Buffalo City Public Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) College was also located in the inner city. The coastal industrial city of East London, which had been unable to establish a significant HE presence in the previous century, now had three university campuses – albeit satellite ones – and a further education and training college.

In 2002, the number of students attending HE facilities in the inner city stood at around 3000 in total (2000 at Rhodes and about a 1000 at others). By 2016, the number had risen to more than 15 000. In 2002, the majority of students in the city were studying part time and commuting to and from the centre to attend evening classes. By 2016, almost all of the students were full time and the vast majority lived in and around the city centre. They were a dominant presence in the city centre, but a virtually invisible constituency as far as the local authority and business community were concerned, until the middle of 2015, when many of them rose up during the #FeesMustFall protests and brought the city to a standstill for almost a week. The mayor and the city council, together with leaders from the business community, joined the university authorities in lambasting the students for occupying and barricading city streets and for their ‘irresponsible and self-destructive’ actions (cf. Daily Dispatch, 27 October 2015). On the list of grievances outlined by the students during the protests, the reduction of fees featured prominently, as it did on student manifestos across the country. Other important grievances related to the quality of the university-supplied and private residences offered to students and the quality of the neighbourhood in which most of them lived in the inner city. Their collective cry related not only to the lowering of fees but also protested against a feeling of being trapped in a crime-ridden inner city. They felt that neither the universities nor the metropolitan authorities had their best interests at heart. The neighbourhood aspect of their political demands was reflected in the fact that students from all institutions joined forces on barricades blocking key inner-city arteries to express their grievances and solidarity (cf. Bank, Citation2018).

This article explores the city-campus dynamic in East London’s inner city in the light of international experiences and investigates the place-based opportunities for HEIs to play a more instrumental role in shaping the built environment and economic profile of a struggling former industrial city such as East London. Indeed, in the same period during which thousands of students arrived in the city, tens of thousands of industrial jobs were being lost in the city-region as a result of the impact of post-apartheid neo-liberal economic policies and, later, the global financial crisis of 2008. The downswing started with the closure of the former homeland industrial parks in Dimbaza and Butterworth on the outskirts of the city after 1995, when apartheid-government subsidies for regional industry were withdrawn. Without support from the state, many of the factories closed, leaving more than 50 000 people jobless in the East London hinterland. In the city itself, a well-established local textile industry that had been operating since the 1930s was swept aside by Indian and Chinese competition, leaving thousands more jobless (Bank, Citation2018).

In 2000, the city finally announced the opening of a new industrial development zone (IDZ) next to the harbour to attract industry back to the city. The move helped to maintain the auto-manufacturing sector anchored by Mercedes-Benz South Africa and slowed the pace of factory closures. But, after 2008, not even the IDZ could stop the city’s industrial sector from collapsing. Notwithstanding the substantial investment in the IDZs, they still failed to meet expectations. Between 2002 and 2014, the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) transferred R6.9 billion to the zones to fund their operations and capital infrastructure.

Table 1 summarises elements of IDZ performance in relation to expenditure as an indication of the success of the programme. The data indicates that, arguably, none of the IDZs justified their relative investment. The ELIDZ failed to raise private investment to match that provided by the public purse: the private sector contributed only 83 cents for every rand of government expenditure. Every direct job created at the ELIDZ cost the state R1895 000. In addition, none of its investors generated exports (cf. Bank, Citation2018). The performances of Coega and the East London IDZ raise significant questions about the success of these capital-intensive projects in terms of rapidly creating jobs and opportunities in the city and what other opportunities these cities might turn to in order to reshape their economic futures.

The urban deindustrialisation crisis that gripped East London and its industrial hinterland after apartheid was similar to the crises that had unfolded in many northern cities several decades earlier with the flight of industrial production to Asia and the hollowing out of inner cities as workers left or populations moved to the suburbs. Apartheid planning had kept some of these processes at bay in cities like East London, which benefitted from industrial subsidies, but this changed after 1995 (cf. Beall et al., Citation2002). In the wake of the urban crisis in northern industrial cities, a raft of new policies and approaches were adopted to enable them to adapt and change with the times. Many of these policies and approaches have focused on how HEIs can help to transform post-industrial cities or attract new talent and opportunities for development. However, in the case of East London and other struggling industrial cities in southern Africa, government policies have been largely shaped by a belief in the prospect of re-industrialisation, and a refusal to engage with the wider urban crisis of late capitalism and to consider alternative modes of economic and social development. Many of the new strategies that have been adopted elsewhere are based on creative public sector investment strategies and the growth of non-industrial sectors, such as education, services and tourism. This article will consider how some of these strategies and approaches have emerged, before returning to East London and the possible role of HE and non-industrial sectors in the city’s redevelopment. The primary aim of the discussion is to raise awareness of alternative opportunities for investment in place-based development outside of the current IDZ focus, which has proved costly and generated few long-term benefits for the city.

2. Universities and the city-regions

In a recent high-level report, An Avalanche is Coming: Higher Education and the Revolution Ahead, Barber et al. (Citation2013) argued that a ‘major crisis’ is developing in HE because current delivery models fail to meet global requirements. They claim that high levels of unemployment across the world, especially among the youth and university graduates, show that universities are not connecting effectively with wider society and the economy. They also argue that university ranking systems are increasingly shaping HE priorities, with most universities actively trying to climb these tables in order to attract more research funding and better students while not necessarily prioritising the employability of their graduates in their urban and regional contexts. Barber et al. argue for greater recognition of a wider diversity of types and forms of HEI that perform different functions and meet different needs, creating a pluri-versity rather than uni-versity system. They believe that such diversity would allow for greater responsiveness to local economic and social challenges. In fact, they suggest that:

There are two essential outputs of a classic university: research and degrees [though it should be pointed out that it is perfectly plausible to do one without the other] … We can add a third university output which has become increasingly important in recent decades: the role of universities in enhancing the economic prospects of a city or region. (25)

In the international development literature, there has been a growing recognition that universities have had an important role to play in urban and regional development for quite some time. The view that universities are somehow ‘mired’ in places from which they cannot escape has increasingly given way to the idea of universities as agents for the transformation of place (cf. Perry, this issue). As job losses affected large industrial cities in Britain and the US Rust Belt, inner-city precincts entered a downward spiral of poverty, crime and urban decay. In Britain, the creation of the metropolitan university model was a response to this inner-city decline. The aim of the new institutions was to help impoverished inner-city communities recover by combining opportunities for academic study with community outreach and engagement. In the US, the state attempted to strengthen the role of inner-city community colleges to slow down ghettoisation and inner-city decay. In both cases, universities were seen as enabling centres for poor communities to rebuild capacity. In South Africa, a similar community engagement function was imposed on all universities after 2000 to assist their surrounding communities.

Metropolitan universities in Britain and community colleges in America did help to re-articulate the role of universities as socially engaged with local, poorer neighbourhoods, rather than simply serving the interests of national elites and the middle class. In US, the creation of Land Grant universities during the nineteenth century was a response to the idea that HE was becoming privatised and only accessible to wealthy, upper-middle-class Americans. The Land Grant system aimed to extend access to HE geographically to every corner of the country and to allow those with academic ability to study close to home at lower low cost. The Land Grant system also explicitly set out to modernise and transform the American countryside through the application of science, innovation and technology to social and economic development (Rossi, Citation2014).

In recent years, how the role and function of inner-city universities is viewed has changed significantly. In the 1990s, a new vision of universities as place-makers emerged in Britain as ideas of regional development became prominent in the policy discourse under the Labour government of Prime Minister Tony Blair. From around 1997, universities were seen as potential drivers of a new knowledge economy in struggling regions, such as the British Midlands and industrial North. The goal was now to link HEIs across regions and cities by integrating their missions with those of private and public stakeholders in order to foster regional innovation. New institutional structures were created to facilitate partnerships among government, industrial and university partners. John Goddard and his colleagues at Newcastle University embraced the new approach in the north-east of Britain by advocating a new ‘civic university’ model that allowed the university to lead place-based development. The underlying premises of this work were also articulated in a number of position papers for the European Union (cf. Goddard & Vallance, Citation2013).

Some efforts to realign universities so that they had a greater impact on local development were successful, but problems with the model also emerged. For example, many firms and universities reaped greater benefits by engaging with partners and peers globally rather than regionally. It was also found that the most intense competition between institutions was often regional, which made it difficult for them to work together. Many universities felt their reputations would be compromised or diluted through regional collaboration with adversaries. Competition between universities, as has also been the case in East London, can act as a major barrier to place-based development. The fact that universities are reputation-driven institutions that attract resources and students on the basis of their unique identity makes inter-institutional co-operation difficult. But perhaps even more of an issue at British institutions has been the perception that enforced partnerships and redefined roles and responsibilities represent an assault on academic freedom and critical thinking. Many academics oppose what they view as a new managerialism within modern British universities. Bill Readings (Citation1996) was one of the first to suggest that the additional pressure placed on academics to adopt broader public engagement mandates was bound to leave universities ‘in ruins’ as they became ‘captured’ by other agendas, especially private interests. Outspoken critics, like Frank Furedi (Citation2004), have argued that privatisation and other external pressures have basically extinguished robust debate and academic rigour at many universities, leading to what Furedi calls their ‘infantilisation’ and impotence as progressive institutions of social change.

Notwithstanding such concerns, the new public engagement agenda has continued to gain support from governments in the global North, although the geographical scale has shifted from the regional- to the city-scale since the global financial crisis of 2008. Policymakers have increasingly argued that universities are more effective agents of change within their primary geographic locations – like their host cities – rather than their broader regions, where co-operation can be difficult. British policymakers have sought, for example, to promote the idea of ‘science cities’, stressing the urban rather than regional scale. Charles et al. (Citation2014) argued that the scalar shift from region to city represents an attempt to overcome difficulties that had been experienced by regional bodies and co-ordinating institutions in earlier policy frameworks. Using the Greater Manchester and Newcastle metropolitan areas as case studies, they showed how local universities had become part of a new city-region policy articulation, but still concluded that ‘under post-crisis austerity, changing funding mechanisms and more pressures to compete, universities find it difficult to meet expectations’ and also that ‘institutions find themselves in a far more competitive environment with less incentive to collaborate’ (Citation2014: 18). They suggested that insufficient attention had been given to the tight financial constraints within which many universities operate and how difficult it can be for institutions with little third-stream income to deviate from their primary teaching and learning mandates (25).

In the US, the conception of universities as agents of place-based transformation has been largely focused at the precinct or neighbourhood level in the twenty-first century. The transformation of university-aligned precincts such as Silicon Valley, which is associated with Stanford University, or the new Boston Innovation District, which is associated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), have emerged as shining examples of the potential place-based agency of universities in terms of promoting urban development (cf. McWilliams, Citation2015). Based on these and other cases, including the former Rust Belt, steel city of Pittsburgh, urban geographer Richard Florida predicted the rise of a new creative class in university-city precincts that would positively transform urban America in the twenty-first century. He suggested that mayors and business leaders needed to focus on working closely with university chancellors and academics to transform the quality of inner-city neighbourhoods and, by extension, entire cities and regions. He predicted that, if these players could combine forces and bring talent, technology and tolerance together, new cities would be created based on new economic forms (Florida, Citation2004, Citation2017).

Florida’s predictions appear to have come true in Barcelona, Boston and San Francisco, where new inner-city precincts have attracted talent and capital and new jobs have been created. The question that remained, however, was: would the creative class model work across the board, including in lagging, bankrupt cities such as Detroit, Cleveland or St Louis, where capital had fled and talent was moving and staying away. Many argued that the Silicon Valley-style technology-driven urban regeneration model had little capacity for broad-based urban transformation because it was elitist and exclusionary. Inclusive development is undermined when real-estate capital follows innovation and job creation to drive up property prices beyond levels that are locally affordable, creating gentrification and driving locals out of their historic neighbourhoods. If this tendency is not controlled and managed, the benefits of inner-city urban growth projects can be lost. The evidence nevertheless also suggests that improved, dynamic university–city relations can still be powerful mechanisms for creating new jobs and economic activity, if they are managed responsibly and combined with other development strategies, including re-industrialisation or tourism development. The evidence suggests that in de-industrialising cities, public sector entities, like hospitals and government departments, can combine with HEIs to drive new urban growth. Where private capital is still reluctant to invest, collaboration between public sector anchors can lay the platform for urban renewal in declining precincts in old industrial cities.

3. The East London inner city and the city-campus dynamic

East London’s city centre developed rapidly at the end of the nineteenth century and again as the city was industrialised after the Second World War. The key public anchor institutions in the city centre, such as the city hall, the public library, market square and main commercial anchors, had already been established by the turn of the twentieth century, when the city was still a small trading port. The city grew rapidly from the 1940s as new suburbs and townships were created to accommodate the growing urban population. This energy revived the city centre as old civic buildings were repainted and refurbished and the old high street was modernised. At this time, many Victorian buildings were torn down and replaced by multi-storey, modern, glass-and-iron high-rise buildings. The council built new offices in the city centre. However, with the arrival of apartheid planning the mood in the city changed as new towns were created in the Transkei and Ciskei, shifting the focus of development in the region away from East London, its harbour and city centre (Bank & Qebeyi, Citation2017).

By the 1970s, the future of East London as a city was shrouded in political uncertainty. Many wondered whether it would be absorbed by the surrounding ethnic homelands. This destroyed business confidence. The city’s plight was compounded by the apartheid economic policy of industrial decentralisation, which incentivised white industry to move away from the cities to industrial parks in homeland towns. Between the 1970s and the 1990s, East London declined as an industrial city and urban centre. After democracy, the fortunes of the city were partially restored when the Ciskei town of Bisho, 50 km outside East London, was made the new administrative headquarters of the Eastern Cape Province. From the late 1990s, a large black middle class, many of whom were employed in the civil service, settled in the city, reviving its real-estate and retail sectors. Although it took a while for this middle class to commit fully to the city, by 2000 the adoption of East London as a home-coming city for the new black middle class was in full swing, with the construction of several suburban malls and the growth of a black property market in the city (Bwalya & Seethal, Citation2015; Bank, Citation2011, Citation2018).

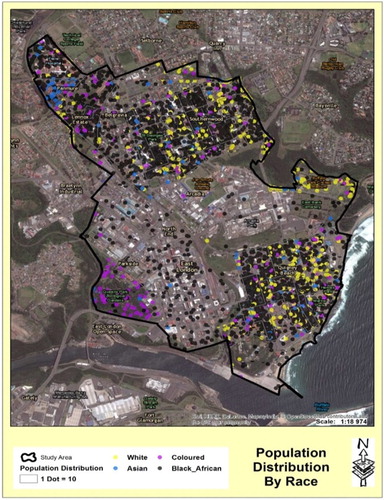

By 2010, more middle-class black families were buying new homes in East London than whites. This trend started in the inner city, where properties were cheaper in the mid-1990s, but spread across the entire city after 2000 (ibid). The inner-city suburbs of Quigney and Southernwood had been white-dominated in the early 1990s but were over 50% black by the early 2000s. In 2014, 80% of the population of these suburbs was black and many residents were also relatively young (see ). Meanwhile, the drift of wealthy residents, black and white, to the urban edge had negative implications for the city centre, which entered a downward social and economic spiral. Like many city centres in South Africa, a lack of investment in infrastructure, together with commercial and retail decentralisation and the rise of slumlords, meant that the inner city became increasingly crime-ridden and economically depressed.

In 2015, during the #FeesMustFall protests at the University of Fort Hare and Walter Sisulu University, the inner city was taken over by students, who built barricades and bonfires on Fleet, Oxford and Curry Streets, making the area a no-go zone for almost a week. They argued that universities and the city council had been treating them poorly. They said that the city did not seem to care if they were raped or assaulted on their way home from lectures and that the university had promised them transport, internet and other services which had not been delivered. They also complained that accommodation in the inner city was generally over-priced and that city store-owners who depended on them for business treated them badly. Meanwhile, some local residents complained that the downward slide in the inner-city suburbs was a result of the influx of so many students. They said that they did not know their neighbours anymore and that the students were just ‘passing through’. Bwalya and Seethal (Citation2015, Citation2016) reported that local residents associated the presence of the students with a range of problems in their neighbourhoods, such as rising crime, drug houses and prostitution. The city council seemed to support this view and frequently blamed the students for the inner city’s problems, accusing them of causing crime and instability. Contrary to these suggestions, our research found that most students shared many of the same concerns as local homeowners and tended to stay locked up in their residences after dark because of the dangers associated with their neighbourhood (cf. Bank, Citation2018).

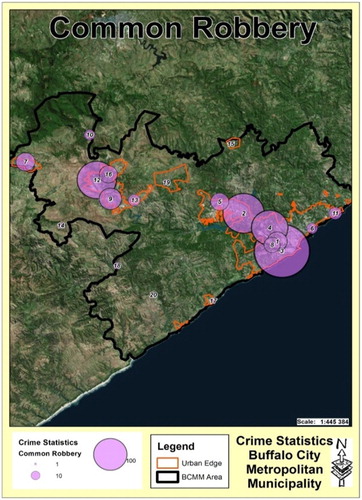

demonstrates the concentration of common crime in the inner city in 2015. The figure shows that the highest incidence of common crime was in the city centre. This is where most students live. highlights the demographic composition of the inner city by race, supporting the observation that the racial composition of the inner city has changed since the 1990s.

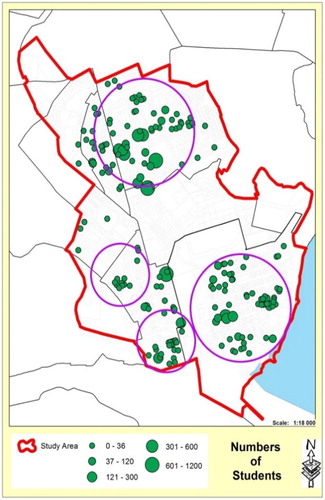

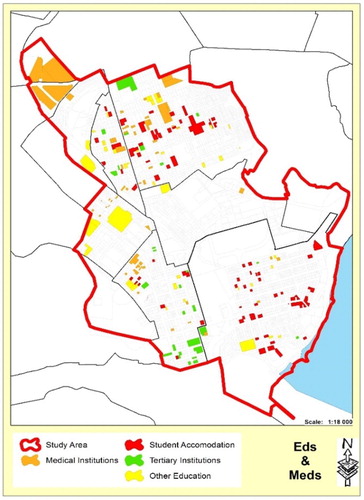

The 2011 census data also show that the inner city has a youthful population relative to the other parts of the city. provides a spatial outline of students in Quigney and Southernwood, as well as in the CBD. In 2015, there were well over 10 000 students in the inner city, with about half of them living in official residences, while the other half lived in rented rooms. shows the location of HE and medical facilities in the city centre and surrounding suburbs.Footnote1 It shows a very high concentration of the ‘Eds and Meds’ – education and medical institutions – in the city centre. In cities like Detroit, public sector anchors, especially Eds and Meds, have been critical to the creation of anchor strategies for inner city renewal and regeneration. The anchor strategy entails that anchor institutions have the capacity to shape their surroundings, enhance the quality of life for residents and drive regional economic performance because of their size and relative importance to the local economy (Dever et al., Citation2014: 1). Their local rootedness and community links are such that they are acknowledged as playing a key role in local development and economic growth, representing the ‘sticky capital’ around which economic growth strategies can be built. The starting point for these strategies has often been to consider whom these institutions pay and employ. The goal, then, is to ensure that as many of these people as possible, together with the students and clients, live and spend their resources within the inner city. One of the first challenges in many of the US cities has been to persuade middle-class students to move into the city centre, which has already occurred in the case of East London.

Figure 4. Eds and Meds in the city centre.

Note: We would like to thank Dean Peters for generating these charts for the Ford report.

Table 1. Expenditure and performance indicators for IDZs in South Africa for 2002/2003–2013/2014.

In October 2015, a survey of more than 3000 matric scholars was conducted by the former white, C-model school and black township schools in the main Eastern Cape cities of East London, King William’s Town, Mthatha and Port Elizabeth.Footnote2 The survey explored the post-school educational aspirations of the scholars and their views of the cities in which they lived and the local universities. In East London, 600 scholars, mostly black and Xhosa-speaking, were asked what they thought of the city centre: 50% described the place as ‘overcrowded and dangerous’, while a further 29% said it was ‘dirty and run-down’. Only 10% felt that the city centre was vibrant and dynamic and only 6% felt it would be a safe place to live and study. Scholars in Port Elizabeth and Mthatha had a more positive view of the inner city than their peers in East London. This is a problem for both the city and the local HEIs because it means that, in general, only those students who could not afford to move out of the city chose to live in East London’s city centre.

In East London, it was also revealed that only 15% of the scholars who wanted to go to university chose the University of Fort Hare or WSU (in other words, the local choices), while 25% said they would prefer to go to Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in neighbouring Port Elizabeth and the rest had aspirations to study outside the Eastern Cape. A total of 71% of the students stated that Port Elizabeth was the most appealing city in the province, while 22% said that they still preferred East London, despite the perceived dangers of the city centre. In the longer term, over 70% of the 600 East London scholars interviewed saw themselves settling in other cities in South Africa (25% favoured Cape Town, 20% Durban and 17% Johannesburg). Only 10% viewed Port Elizabeth as the place they would like to end up and a mere 7% looked forward to remaining in East London. By contrast, more than 25% of the scholars interviewed in Port Elizabeth saw themselves settling in their own city. In Mthatha, the figure was even lower than in East London, with 3% wanting to stay on there.

The results of the scholar survey show that, despite new investment in an expanded HE sector in East London’s inner city, neither the universities nor the precinct in which they are located are seen as attractive by talented youth in the city. Overall, the results show that the scholars preferred to study in larger cities than college towns due to the lifestyle attractions and part-time employment opportunities on offer in those places. The perception that East London was unable to offer students access to an attractive, vibrant place with lifestyle and job opportunities, together with access to good-quality HE, meant that it was unable to compete with Port Elizabeth and other cities outside the Eastern Cape. The negative perception of the city was reinforced by the finding that only 7% of those who had signed up to go to university believed that they would end up living in East London.

Analysis of the different models available for city-campus development has shown that cities with certain characteristics are better placed than others to take advantage of a positive city-campus dynamic. First, the location of universities within the existing urban fabric, especially in the city centre, is a distinct advantage. Campuses located outside the city centre, on the urban edge, are more difficult to integrate into the city socially, physically and economically. Second, the availability of vacant land, especially government-owned land close to campus is a distinct asset, since it offers ready opportunities for city-campus expansion. Third, another significant advantage is the existence of other public sector anchors, such as museums, hospitals and government departments, in the vicinity of the campus to support urban regeneration projects. In the case of Detroit, urban regeneration has been predicated on an anchor strategy involving Wayne State University, the Henry Ford hospital, the Detroit Institute of Arts and other museums and galleries. The presence of students in the inner city, as well as business and public sector partners, strengthens the mix in terms of stimulating urban regeneration.

In the case of East London, many of these opportunities are present. The greatest asset for the city is the proximity of the different campuses to one another within the inner city. However, there is currently no co-ordination among the colleges and universities concerning knowledge production, residential accommodation, use of sports facilities and other issues of common concern. None of the universities is especially committed to the city, nor does the municipal authority appear to favour the universities. In fact, UFH, WSU and UNISA have always operated in silos and in competition with each other instead of planning and engaging in collaboration and support for each other’s niche areas of specialisation. The presence of these institutions in the city has generated neither a profitable nor a significant stimulus for growth and development in the city to the extent that would be expected from such a competitive advantage. The WSU–Fort Hare–UNISA library project in the inner city is the only significant collaboration among the universities. The project took years to broker and experienced delays over various institutional disagreements. If one includes the Buffalo City TVET and the city hospitals that also have accommodation, recreation and educational needs, there is considerable scope for partnership and collaboration among the institutions in the city centre. The absence of collaboration undermines the potential for cost-effective, efficient delivery of HE in the city, as well as much of its potentially beneficial economic impact.

Another opportunity for inner-city regeneration is presented by the existence of a large lot of well-located vacant land, which could be used for student housing and catalytic projects such as an innovation district and business school. The concept of innovation districts has been hailed as one of the new strategies for redevelopment of declining cities especially the post-industrial cities that have been plagued by a plethora of challenges and faced a downward spiral in their economies. In cities like Boston and Barcelona, vacant inner-city land has been converted into multi-use zones for new start-up companies and projects for recreation, heritage and sports and tourism development. These options are possible in East London, where 12 hectares of unused, former Transnet land, known as the Sleeper Site, is located within a few hundred metres of all the campuses and hospitals in the city centre. The land connects the CBD to the beach front and is approximately the same size as the existing CBD. The Sleeper Site belongs to Buffalo City municipality, but has not yet been allocated for development. The city needs to invest in the local economy so that jobs are created and investment is attracted into the innovation hub. The city must draft zoning plans that promote a dynamic physical realm that strengthens proximity and knowledge spill-overs. The city authorities in East London need to take a leadership role in the development of the Sleeper Site since the land belongs to them. In addition to these initiatives, the city must also explore ways of connecting the inner city as a knowledge production zone to the industrial development zone on the west bank of the Buffalo River. The university sector could collectively be seen as a science park for the industrial development zone. This would facilitate close communication and co-operation among the business, industry and HEIs in the city. Opportunities exist to expand the universities’ science and engineering faculties and a business school is needed in the city.

4. Conclusion

The blindness to opportunity in the case of Buffalo City is a product of historical and political factors that resulted from the city not being able to establish its own metropolitan university during the economic and industrial boom of the early apartheid years. In Port Elizabeth, the University of Port Elizabeth was created in the 1960s and later reconstituted as the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University by merging a number of HEIs into a comprehensive city-based and committed university. This did not happen in East London despite the fact that the National Working Group for Higher Education reported in 2002 that the city could become a significant economic growth node in the province but would ultimately need better HE to achieve this. The recommendation to establish a metropolitan university was ignored in favour of a series of satellite campuses in the city. This has meant that Fort Hare and WSU arrived in the city without regarding themselves as being universities of the city. They feel that they have developed their Buffalo City campuses because of the demand for HE in the city and not because the city is their home. With their main campuses elsewhere – in Alice and Mthatha, respectively – the universities of Fort Hare and Walter Sisulu have continued to primarily embrace their rural base, which is connected to forms of African nationalism that view rurality, cultural authenticity and rural development as primary focal priorities for these universities. These identity and ideological issues have cultivated an anti-urbanism that constitutes a barrier to greater urban participation in what was historically seen as a white settler city (see Bank, Citation2018).

In the case of Fort Hare, the power of Alice within the liberation narrative of South Africa as the alma mater of the ANC makes it difficult for the university to claim the city as its primary home and future growth node. This was clearly articulated again during the Fort Hare centenary of 2016, when Fort Hare re-affirmed the importance of its historic home in Alice, making its mother campus the site of all significant centenary celebrations. The East London campus was largely ignored, despite significant new investment there, such as the R200 million for the joint WSU, Fort Hare and UNISA library, and a growing urban student population. WSU has adopted a similar attitude to East London, where an increasing number of its students are based; indeed, in the past three years student numbers have increased by approximately 20%. The failure to take advantage of the multiple opportunities offered by the city-campus dynamic in this struggling secondary city in South Africa is a serious problem for the development of the region. Indeed, in the wider context of the collapse of the productive economy in the region and the far-reaching economic impact of deindustrialisation, there is an urgent need to rethink the roles and functions of HE in the city and its relationship to inner-city regeneration and regional economic development in general. The new black middle class in the city has a strong association with both Fort Hare and WSU and also associates strongly with the city today. However, the identity of these institutions has not been brought into the city. As urban anchors, they could help transform the entire image of the city as a new progressive African city. However, given the poverty and joblessness situation in the Eastern Cape and the positive outcomes associated with the metropolitan university model in Port Elizabeth, a case might also be made for the creation of a new comprehensive, metropolitan university in the East London city centre, which would drive the growth and development of the city.Footnote3

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The results represented in and were collected by teams of Fort Hare students who worked the city centre street by street between July and October 2015 to collect this information. They were employed on the Ford Foundation-funded centenary City-Campus-Region Project, run at the Fort Hare Institute of Social and Economic Research (HSRC). Francis Sibanda was the research manager and Leslie Bank was the project leader on the Ford Project, which ran from mid-2015 to the end of 2016. The authors express special thanks to Justin Visagie at the HSRC for his work on assembling in the article. Justin Visage was a former research director in the Department of Economic Affairs in the Eastern Cape.

2 In October 2015, 3000 questionnaires were administered to matric students who were about to sit their final examinations in East London, King Williams Town, Mthatha and Port Elizabeth. The scholar survey was also part of the Ford-funded City-Campus-Region Project.

3 Pillay and Cloete (Citation2002) came to a similar conclusion at the end of their exploration of different scenarios for HE in the Eastern Cape on the eve of the merger process.

References

- Bank, L, 2011. Home spaces, street styles: Contesting power and identity in the South African city. Pluto Press, London.

- Bank, L, 2018. Beyond auto-freedom: Urbanism, city building and universities on the South African periphery. HSRC Press, Cape Town ( in press).

- Bank, L & Qebeyi, M, 2017. Imonti modern: Picturing the life and times of the South Africa location. HSRC Press, Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Barber, M, Donnelly, K & Rivzi, S, 2013. The avalanche is coming: Higher education and the revolution ahead. Institute for Public Policy Research, London.

- Beall, J, Crankshaw, O & Parnell, S, 2002. Uniting a divided city: Governance and social exclusion in Johannesburg. Routledge, London.

- Blanke, J, 2015. CNN Interview on the Global Competitiveness Report 2014-2015 at World Economic Forum on 4 October 2015.

- Bwalya, S & Seethal, C, 2015. Spatial integration in residential suburbs in east London, South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies 34(2), 20–34.

- Bwalya, S & Seethal, C, 2016. Neighbourhood context and social cohesion in southernwood, east London, South Africa. Urban Studies 44(4), 35–50.

- Campbell, R, Rosenwald, EJ, Polshek, JS, Blaik, O & Bollinger LC, 2005. Universities as urban planners. Bulletin of the American Academy, New York.

- Charles, D, Kitagawa, F & Uyarra, E, 2014. Universities in crisis? New challenges and strategies in two English city-regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 38(4), 1–15.

- Dever, B, Blaik, O, Smith, G & McCarthy, G, 2014. (Re)Defining successful anchor strategies. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper, Cambridge, USA.

- Florida, R, 2004. The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic Books, New York.

- Florida, R, 2017. The New urban crisis: How our cities are increasing inequality, deepening segregation and failing the middle class – and what can we do about it. Basic Books, New York.

- Furedi, F, 2004. Where have All the intellectuals gone. Continuum, London.

- Goddard, J & Vallance P, 2013. The university and the city, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Houghton, DH, ed. 1960. Economic development in a plural society: Studies in the border region of South Africa. Oxford University Press, Cape Town.

- McWilliams, D, 2015. The flat white economy: How the digital economy transformed London and other cities of the future. Duckworth Overlook, London.

- Pillay, P & Cloete, N, 2002 Strategic Co-operation scenarios: Post-school education in the eastern cape. Published by Centre for Higher Education Transformation, Johannesburg.

- Porter, M, 1995. The competitive advantage of the inner city. Harvard Business Review, May-June 1995, pp. 55–71.

- Readings, B, 1996. University in Ruins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rossi, A, 2014. Ivory tower. Documentary. Samuel Goldwyn Films, Los Angeles.