ABSTRACT

Inclusive businesses are complex partnerships between commercial entities and smallholders/low-income communities, to include the latter in commercial agricultural value chains. IBs offer income opportunities for both partners, but are also regarded as empowering the smallholders/communities. To date, IB inclusiveness has been assessed mainly through basic quantitative measurements. However, these measures neglect the complexities of the overall value creation process, and of the inclusion of the beneficiaries within this process. This paper aims at providing a more holistic methodology by assessing the level of inclusiveness based on four dimensions: ownership, voice, risk and reward. Case studies in South Africa show that inclusion of low-income communities lags behind the intended level. Lack of financial resources and skills, reinforced by power imbalance, result in smallholder ownership being limited to land, the community’s voice being compromised, risk being transferred to the smallholder communities and rewards being disappointing for the beneficiaries.

1. Introduction

Ways to facilitate smallholder inclusion in commercial value chains have been discussed, conceptualised and developed in various ways over the last decades (Gradl et al., Citation2012; Arias et al., Citation2013). One way of fostering smallholder inclusion is through partnerships between commercial entities and smallholders/low-income communities. Evolving from more basic outgrower schemes (Bijman, Citation2008), recent developments have led to complex business partnerships that combine multiple standard instruments (collective organisation, equity, lease/management contracts, mentorship, and supply contracts) into unique business structures (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2017a). These complex inclusive businesses (IBs) are hailed to overcome some of the limitations of the more basic instruments, while increasingly providing smallholders and low-income communities with access to commercial value chains.

To determine the impact of IBs, existing measurements, such as the Impact Reporting and Investment Standards (IRIS) and the BCtA Results Reporting Framework (BCtA, no date), predominantly focus on business-related parameters. Particularly concerning agricultural IBs, indicators generally encompass the number of smallholders reached, training provided, and agricultural revenue generated. These indicators are subsequently viewed as comprising an indicator for the developmental impact of the IB (Wach, Citation2012). Such methodologies neglect the complexities of beneficiary inclusion in the overall value creation process within the IB (Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010). Methods of beneficiary empowerment and value-sharing are mostly ignored.

The objective of this methodological paper is to provide deeper insight into, and understanding of, the ‘inclusive’ side of inclusive businesses. Inclusion here refers to the level of participation of the low-income beneficiaries in the value creation process within the IB. The paper aims to offer a methodology to answer the question posed by Wach (Citation2012:3): ‘when is business “inclusive” and when is it simply business?’. This requires a methodological approach to assess the organisational set-up of an IB for the holistic assessment of beneficiary inclusion throughout the value creation process within the IB. Four dimensions of inclusiveness are central to the proposed assessment: ownership, voice, risk and rewards (Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010). The methodology thus measures inclusiveness of the architectural structure by appraising how the smallholders/low-income communities share in the financing and decision-making of the IB, looking beyond how they share in the benefits created by the IB. For each of these dimensions, a distinction is made between institutional inclusiveness and the inclusiveness that is achieved in the actual implementation of the IB. This distinction is critical, as the achieved inclusiveness in practice often lags behind the plans (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2017a). This methodology is then applied to 14 IBs in South Africa. The empirical results illustrate if and how beneficiary inclusion is achieved.

The next section details the methodology, outlines the scoring mechanism, and describes the case studies. Section 3 presents the results for each of the four dimensions. These findings are discussed in Section 4, contextualising the results in the wider debate on the role IBs can play in development. Before concluding, the paper presents recommendations aimed at increasing the level of inclusiveness of IBs.

2. Methodology

To determine the level of inclusiveness of a particular IB structure, four dimensions have been selected to indicate how value creation within the IB is shared between the smallholders/low-income communities and the commercial agribusiness: ownership, voice, risk and rewards (Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010). Each of these dimensions can contribute to overall economic growth, while reducing inequality. Whereas these dimensions are related, they do not necessarily correlate.

To gain further insight into the specifics of these broad dimensions, each dimension is divided into three categories, resulting in 12 categories, overall. The score per category ranges from one (low inclusiveness) to five (high inclusiveness), providing a score for each of the four dimensions varying between three and 15 (). The scoring of each of the 12 categories is done on two levels: institutional set-up and implementation. The institutional set-up score indicates the envisaged level of inclusiveness that can be achieved by the particular IB structure. However, the actual application often lags behind, resulting in a different level of inclusiveness in practice (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2017a; Lahiff et al., Citation2012). Thus, the second score relates to the effective implementation of the IB.

Table 1. Scoring mechanism per category.

The 14 IBs to which this methodology is applied are situated across South Africa and represent a diverse range of sub-sectors (). Using a snowball sampling method, the IBs retained for this study have been selected for their unique set-up, implementing complex combinations of standard instruments: collective organisation, equity, lease/management contracts, mentorship, and supply contracts. These instruments each affect the way in which beneficiaries are integrated in the value-creation process, and have a significant impact on the level of inclusiveness. The studied IBs have been in operation for a number of years, presenting a minimum level of sustainability. This results in better insights into the potential and actual levels of inclusiveness in each of these different structures.

Table 2. Case study description.

Data collection took place between October 2013 and March 2015. To determine the details of the IB structure, semi-structured interviews were conducted with all stakeholders: commercial partner, smallholder representatives, financers, government officials, and other actors, where applicable. Further information was obtained through interviews with randomly selected beneficiaries, which highlighted how these beneficiaries understood and experienced their inclusion. This aspect was important to measure the inclusion of the IB structure in its implementation. These interviews, combined with printed material, made an in-depth case analysis possible. For a detailed description of each of the case studies, see Chamberlain and Anseeuw (Citation2017a).

A few notes need to be made regarding the scoring mechanism. Firstly, the presented assessment relates to the set-up and implementation of an IB as overall business operation. It does not assess absolute numbers, such as the amount of rent received, the value of assets owned, or the number of beneficiaries trained. Whereas this allows for comparing IBs of different sizes, it might exaggerate the extent of inclusion; stakeholders implement a minimum of value-sharing, but generate a high score. Related to this point is the fact that the methodology is not an impact assessment or evaluation; it does not compare a before and after situation, nor does it analyse the performance of the IB or look at either positive or negative effects of the IB. Thirdly, this assessment largely relates to the overall degree of equality within the IB partnership; it does not evaluate the impact on the individual beneficiaries. This is relevant to those IBs that incorporate a collective organisation, the majority of the cases. Whereas the IB, as a partnership, might have a relatively high inclusiveness, this does not necessarily trickle down to the individual members, as became clear from interviews with the individual beneficiaries in a number of IBs. This lack of individual impact is observed particularly where large collectives are involved (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2017b). Furthermore, existing inequalities within a collective are likely to have an effect on the level of impact at an individual level (Sabates-Wheeler Citation2008). Thus, whereas certain smallholders might be impacted upon positively, others could consider the impact of IBs as negative. Lastly, spin-off effects of the IB through community linkages are not included, as these do not pertain to the internal structure of the IB. The methodology presented here aims to provide insight into the value-sharing potential of the structure of IBs as a combination of standard instruments; it is not an overall or individual impact assessment.

3. Results

The methodology outlined in the previous section is applied to 14 case studies, for which the four inclusiveness dimensions are presented here in individual sub-sections. These results are linked to the standard instruments that constitute an IB, namely: collective organisation, equity, lease/management contracts, mentorship and supply contracts.

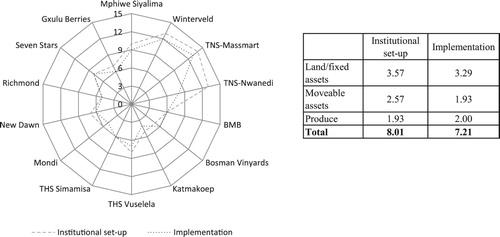

3.1. Ownership

On paper, ownership levels are high where individual smallholders actively farm with a certain level of independence (first quadrant in ). These cases include a mentorship, which by definition leaves full ownership with the mentee (Terblanché, Citation2011). A combination of a mentorship with a supply contract affects the inclusiveness negatively since the smallholder loses ownership over (part of) his or her crop. Subsequent equity in the off-taker partly compensates this loss. Intermediate levels of inclusiveness occur where collective organisations are part of the institutional structure. In our study, all these organisations own the land on which the IBs operate. Either individual landowners have chosen to temporarily transfer their land to the collective, or the collective itself holds the land title. But, whereas the land is owned by the (collective of) smallholders, the moveable assets and produce are at best shared with the commercial partner. Inclusiveness from an ownership perspective is particularly low where land is leased out to a commercial partner. These landowners do not participate in the farming activities. Although this relieves them of any responsibility (financially or operationally), their inclusion is severely limited. In effect, instruments with higher levels of inclusiveness do not compensate for the dominant lease instrument.

In the actual IB implementation, the ownership levels are lower than those on paper, especially where smallholders operate independently (). Often, these individuals lack the financial means to establish their own farms and depend on short-term land leases from the government. The South African government places stringent conditions on these leases, requesting the lessee to share responsibility of the farming activities with a mentor or strategic partner. Due to these land ownership limitations, fixed asset ownership is only achieved collectively, by those smallholders who are organised in a collective. Better results can be achieved when moveable assets are considered, but once again, limited financial means prohibit individual smallholders, as well as beneficiary collectives, from accumulating productive assets. In contrast, produce ownership for individual smallholders, although still very low, is higher than envisaged where beneficiaries are able to produce both independently and under contract for a commercial off-taker, a point strongly illustrated by Mphiwe Siyalima.

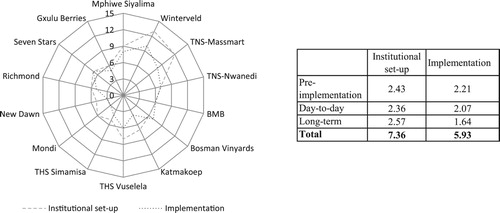

3.2. Voice

In line with the ownership dimension, individually operating smallholders are, on paper, able to obtain the highest participation in decisions pertaining to ‘their’ land (). Asset ownership gives them the right to participate in decisions affecting these assets (Baumann, Citation2000; de Koning & de Steenhuijsen Piters, Citation2009). Some inclusive instruments can assist in obtaining a higher level of decision-making power for smallholder farmers, while others potentially sideline them from meaningful participation. Mentoring NGOs can express the interests of smallholders and open information channels (Cheyns, Citation2014). Collective organisations are seen to increase the overall voice of the beneficiaries, although the individual’s voice is compromised (Hall et al., Citation2004; Baden, Citation2014). Beneficiaries who belong to such collective organisations, mostly on the left-hand side of the spider web in , are in a lesser position to individually influence what happens during both the design and implementation of the project: individual voices are represented through the (democratic) election of the members’ representatives (e.g. Mondi, Gxulu Berries), or individual members have the option to exit the collective at the end of the IB contract (WUFA, THS cases).

The influence on the farming activities further reduces when the IB incorporates a supply or lease/management contract. Whereas a supply contract transfers decision-making power partially to the off-taker, lease arrangements in this study place all the decision-making power with the commercial lessor. However, the limited period of these contracts does give the beneficiary (collective) the option to alter the IB’s construction in the long term. Beneficiaries who have temporarily transferred their individual land to a collective organisation (i.e. THS) can equally opt out of the collective at the end of the agreement, and thus retain the power as to the long-term decisions for activities on their land.

In practice, many cases demonstrate that less decision-making power is transferred to the farmers than was expected. Several reasons can be identified. Firstly, the inherent, significant power discrepancies between the often small-scale farmers and the generally large-scale off-takers or business partners, lead to farmers’ voice, although improved, remaining inferior. This entrenched power disparity is particularly the case in South Africa, historically characterised by biased (racial) relationships (Cochet et al., Citation2015). But whereas several individual beneficiaries, particularly in the Mondi case, remark that they accept, and appreciate, operational control by the commercial partner over the IB, they are frustrated by their lack of voice in the collective organisation and their ability to influence the decisions made by their representatives. Secondly, the lack of financial capacity often does not allow for greater voice, as financial dependency renders the beneficiaries dependant on the commercial partners in any case. This is particularly an issue for those beneficiaries with land access through a short-term lease who lack opportunities for accumulation and are not in a position to make any medium- to long-term plans for ‘their’ farms, as illustrated by Mphiwe Siyalima. Thirdly, the lack of capacity in general, and of capacity transfer in particular, does not allow these voice biases to be overcome. Indeed, whereas IBs, in theory, are designed to develop the beneficiaries’ skills, especially in mentorship and equity constructions, in practice this is often not a priority for the commercial partner (see also 3.4). It also transpires that beneficiary empowerment often takes longer than planned, certainly in the framework of large community set-ups.

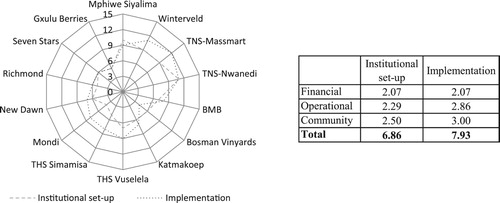

3.3. Risk

The risk aversion attitude of the smallholder farmers (van Averbeke & Mohamed, Citation2006; Patt et al., Citation2010) is confirmed by the cases: the average risk score for the institutional set-up is the lowest of the four different dimensions (). Risk aversion is particularly the case where beneficiaries enter into lease/management agreements where all activities and decisions, and thus also the risks, are transferred to the commercial partner. Individually operating smallholders are the most exposed, especially to the operational risks related to the uncertain farming activities. Whereas these risks can be mitigated by a supply contract or a mentorship, joining a collective organisation adds alternative risks.

In practice, however, risk is related to the effective implementation of the IB. illustrates the point that the average implementation score is higher than the institutional set-up. The power and information asymmetry allows the commercial partner to thus transfer risk to the less influential smallholders, resulting in the highest score for this dimension, when looking at the implementation. Even in set-ups where the commercial partner is fully responsible for the farming operation, it is still able to allocate a share of the operational risks to the smallholders, for example through a profit-share clause in a lease agreement. Most beneficiaries can only gain access to an IB through a collective organisation, further increasing their actual risk exposure through internal and external tensions, such as the free-rider challenge, and the control and influence cost problems (Ortmann & King, Citation2007; de Koning & de Steenhuijsen Piters, Citation2009).

The wishes of individual members do not align with those of the collective, causing friction that can negatively impact on the performance of the IB. In some cases, these frictions extend to the external community in which the IB operates, such as observed in the Seven Stars Trust case. Thus, whereas a collective organisation reduces individual risk exposure, the added complexity nullifies this benefit and in practice results in a higher overall risk to the IB.

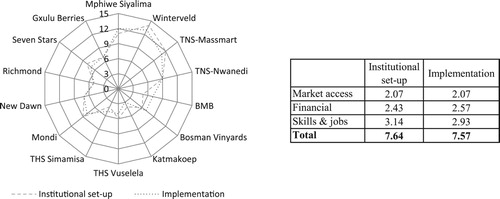

3.4. Rewards

The anticipated rewards, both monetary and non-monetary, for the beneficiaries comprise a main driver for the stakeholders supporting IBs. Our study confirms this anticipation, with rewards being the second-highest scoring dimension of inclusiveness, both in structure and implementation (). In theory, inclusive instruments contribute in different ways. Mentorships and equity allow beneficiaries to directly gain access to knowledge and information. This transfer of knowledge is envisaged in most of the IBs covered in this study. Collective organisations enable their members to reach certain thresholds, either related to off-take volumes, by enhancing the ability to negotiate conditions/margins, or by legitimising demands, such as access to public services or jobs. Equity, lease agreements and supply contracts each ensure a degree of certainty of rewards in the form of an asset base, secure market access or regular rental income, respectively.

This study also illustrates the point that IBs can place pressure on potential benefits. This is often related to the extent and use of benefits, particularly in the framework of larger collectives, and to the inherent nature of the set-up of these IBs where engagement of the smallholders – and with it, the benefits – are limited.

Two observations were made regarding the application of financial proceeds from the IB, in the form of both monetary income and asset growth. Firstly, in collective organisations, monetary rewards can be marginal for individual beneficiaries, notwithstanding that the overall rewards for the collective as a whole are considerable, such as in the New Dawn and Richmond cases. Thus, whereas the inclusiveness score shows that the IB generates collective income, the individual beneficiaries often do not experience any benefits. During fieldwork interviews, individual community members of these IBs often expressed frustration with their lack of benefits, confirming academic criticism that questions the core essence of such set-ups for beneficiaries (Lahiff et al., Citation2012; Binswanger-Mkhize, Citation2014). This pressure on potential individual rewards relates to the misalignment of priorities of a collective with that of its individual members, or where the collective’s priorities differ from those of the (equity) partners. Particularly in cases where the first years of the partnership are marked for (re)development of the farm, cash flows are invested in asset growth instead of dividends to individual beneficiaries, as observed in most of the studied IBs. Collective rewards without individual distribution potentially threaten the developmental objective for, and support by, the individual community members of these IBs. Therefore, the Seven Stars Trust, which engages with individual landowners, has prioritised financial rewards to its members, resulting in both an asset growth for the collective (funded by government grants) and cash payments for the individuals. Payments to individual members are further delayed if their (collective) equity is financed through loans that need to be repaid before dividends can be declared, such as with Blue Mountain Berries. In contrast, the THS cases illustrate the fact that individuals can benefit directly from financial streams, despite being part of a collective. It needs to be said, though, that it is the commercial partner who fully controls these payments, refusing the cooperatives the right to generate assets to allow for diversification of income-earning activities or build community infrastructure. Furthermore, although direct payment to the individual beneficiary results in a higher inclusivity score, this score does not reveal the disappointingly low amounts received by the individual beneficiaries.

Secondly, the engagement of smallholders and community members in the IB tends to be limited. This is attributable to, among other things, a lack of capacity, the initial structure of the IB, and the unequal power relations between smallholders and commercial entities. As a result, the social benefits for the smallholders are often minimal. For example, despite significant promises, job creation for beneficiaries remains limited due to the protection of rights of existing workers (Richmond), a lack of skills to engage in more senior positions (Mondi), and an unwillingness among the beneficiaries to engage in low-skill labour activities (Seven Stars Trust). Equally, skills development programmes have either been absent or have been disappointing in their results (New Dawn). Low commitment not only on the side of the commercial partner to invest in skills development, but also from the beneficiaries selected for training programmes, have led to unsatisfactory outcomes.

Thus, in practice, the rewards for the smallholders and beneficiaries are often less advantageous than were expected (). It thus happens that beneficiaries observe economic activity on ‘their’ land, but reap little, if any, rewards for themselves.

4. Discussion

Assets create dependencies between a smallholder and the agribusiness partner, and as such form the basis of an IB and the institutional set-up of that IB (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2017b). Johnson et al (Citation2016:296) confirm that ‘assets can influence the design, implementation, and outcomes of programs by determining who participates (and who does not participate) in the programs as well as how and how much they benefit’. Furthermore, assets are important, considering the positive relationship between asset ownership and development (Carter & Barrett, Citation2006; Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2011). Assets provide people with a means by which to earn an income, which allows them to structurally reduce their levels of poverty (Carter & Barrett, Citation2006). In particular, a more equal distribution of assets seems to drive development (Birdsall & Londoño, Citation1997; Deininger & Olinto, Citation2000). However, as demonstrated in Section 3, the smallholders reviewed here mostly enjoy ownership of land. Full ownership does not go much beyond this, with fixed and mobile assets and produce shared with a commercial partner, if it all. The dependency of these commercial partners thus does not stretch further than the smallholders’ land. This confirms the lack of resources and skills of the smallholders that are needed to independently, as collective or individual, operate their land. There is no additional asset base beyond land that allows smallholders to enter onto a path to accumulation, which questions the potential for IBs to drive development. Indeed, ownership needs to be combined with effective capacitation of the beneficiaries, and the commercial partner needs to take cognisance of the need for short-term financial rewards for these beneficiaries (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2018).

Whereas ownership implies access to a resource, voice refers to the ability to use and control this resource. Power asymmetry allows for the more powerful partner to influence the terms of the contract to its own favour (Argyres & Liebeskind, Citation1999), in effect breaking the relationship between ownership and voice. Smallholder farmers and low-income communities are particular groups whose voice is often not heard (Stringer et al., Citation2008; James & Sulemana, Citation2014). Their low socio-economic status (Friedmann, Citation1992; Béné, Citation2003) and the existing power barriers (Cheyns, Citation2014; Nelson & Tallontire, Citation2014) are among the challenges that smallholders face when dealing with other stakeholders in the commercial value chain. By definition, commercial agribusinesses that enter into an IB have a particular interest in the inclusion of smallholders, albeit their prime motivation ranges from mere access to smallholders’ resources, to philanthropic reasons. Thus, an IB in theory offers opportunities to empower beneficiaries by allowing them to gain access to the decision-making processes. Nevertheless, challenges in practice have been found, specifically regarding compromising the smallholders’ voice to the benefit of more powerful stakeholders either inside a collective of beneficiaries, or vis-à-vis the commercial partner (Bernard & Spielman, Citation2009; Hendrickson et al., Citation2014). The context where collective organisation is imposed on low-income communities that has been observed in many of the IBs does not allow for a strong, united voice, with only the relatively small and established cooperative in the SST being able to represent their members’ interests. Not only are individual members side-lined, through the inherent power imbalance, the commercial partner in an IB can abuse its power to exclude the smallholders’ collective from several decision-making processes, as observed in among others the THS cases. Our study shows that equal decision-making is rarely obtained, even in cases where ownership should ensure the beneficiaries a position to exert an impact on the activities of the IB in general (e.g. Katmakoep Boerdery), and on their assets (particularly land) specifically. The motivation and commitment of the commercial partner to beneficiary development plays a significant role in the engagement of the beneficiaries in the IB (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2017b). The result is that, despite ownership over resources, the smallholders are denied control over these assets (Béné, Citation2003; Fréguin-Gresh & Anseeuw, Citation2014). Insufficient beneficiary empowerment places a question mark over the long-term ability of the beneficiaries to become independent players with increased participation in the agricultural sector, and hence the attainment of true transformation of the primary agricultural production structure as envisaged by the South African government (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2018).

Poor smallholders are highly risk-averse, considering the immediate and severe impact that harvest failure would have on their livelihoods (Dercon, Citation2004). As part of their risk-minimisation strategy, they limit themselves to low-risk activities, which also tend to be low-income activities. This diverts these households from higher-earning activities that could effectively break the poverty trap (Dercon, Citation1998; Kamanga et al., Citation2010). Market imperfection is often cited as a reason for the risk-aversion strategy: poor smallholders do not have access to risk-mitigating insurance, and lack collateral to obtain credit (Patt et al., Citation2010; Dercon & Christiaensen, Citation2011). IB participation can potentially serve as a risk reduction strategy: it can diversify the smallholders’ activities, enable access to inputs or credit to obtain these inputs, and spread risk over a collective (either with other smallholders or with a commercial partner). Conversely, commercial engagement incurs risks related to a potentially higher level of financial investment, and working with a more powerful partner (Berdegué et al, Citation2008; Sivramkrishna & Jyotishi, Citation2008). Considering the information asymmetry between smallholder farmers and commercial agribusiness, it is likely that both decision making and decision control lies with the commercial partner, as confirmed by the analysis of the voice dimension. Our study observed that individual beneficiaries can certainly experience alleviated risk in the framework of an IB, even when they operate as individual smallholders. Financial exposure of the beneficiaries is minimised through grant funding or favourable financing. The operational expertise of the commercial partner restricts the operational risk, albeit with the loss of decision-making power. Nevertheless, the risks related to the highly complex and multilevel constructions in practice place severe strains on the beneficiaries. Collective organisations are often established specifically for the IB. The leadership thus needs to build a cohesive collective, manage its multifaceted internal affairs and IB matters, and must establish its position in a potentially volatile environment of excluded community members. This makes for an uncertain business partner. An equally important finding is that the commercial partner indeed seems to be able to transfer an unequal share of the IB-related risk to the beneficiaries. This is illustrated by the THS cases where individual landowners effectively rent out their land, but their income depends fully on the overall production of a collective organisation, whose supply for THS is negligible. shows that the implementation scores, only for this dimension, are higher than the institutional set-up scores.

For IBs to become a pathway to rural development and poverty reduction, not only do the beneficiaries need to have a fair share in ownership, voice and risks, the rewards from the IB need to enable them to gain a way out of poverty. It is often argued that access to assets alone will not result in income growth, but that this needs to be combined with market access (Sabates-Wheeler Citation2008). This aspect refers to both input and output markets (da Silva & Ranking, Citation2013). Access to input markets can generate higher farm productivity, and access to crop markets allows for the absorption of bulk production, although not always at a more favourable pricing (Kirsten & Sartorius, Citation2002). Through participation in a network (the IB), participants gain access to new knowledge through repeated interaction with other members in the network (Inkpen & Tsang, Citation2005). Thus, IB participation grows the social capital of the beneficiaries, allowing them to potentially become independent farmers. This is a particularly strong argument in support of IBs, as these are characterised by a large knowledge gap between the beneficiaries and the agribusiness. Reality shows that the transfer of social benefits is subordinate to the economic performance of the IB.

Overall, despite the fact that smallholders and low-income communities are integrated into commercial agricultural value chains, their effective inclusion in the IB processes remains limited, certainly in the implementation. Inclusion takes time, requiring a long-term commitment from both partners, and the corresponding management of the beneficiaries’ expectations.

5. Conclusion

Applying an in-depth, holistic methodology, this paper analyses four dimensions, i.e. ownership, voice, risk and reward, which characterise the degree and the manner in which smallholder farmers/low-income communities are included in complex IBs. A variance in levels of inclusiveness results from the instruments that are combined in the IBs. The analysis shows that the complexities of the value creation process within an IB obstruct the effective inclusion of the beneficiaries, as collective but particularly as individual, even where the IB performs positively as a project. Indeed, IBs can be profitable, but benefits for smallholder farmers/low-income communities remain often marginal.

Firstly, although these beneficiaries have a certain level of asset ownership, this does not necessarily mean they have control over their assets. Ownership does not extend much beyond land, with moveable assets and produce, at best, being shared with a commercial partner. Beneficiaries regularly become mere rent-seekers. Secondly, while the beneficiaries might have a fair share in the decision-making processes within the IB on paper, they need to be empowered to become relevant negotiators. Practice shows a large divide between commercial partner and beneficiary, both in skills required for the management and operation of the farm, and in overall business acumen and financial participation. Effectively, the decision management and decision control are both in the hands of the commercial partner. Thirdly, the beneficiaries limit their risks through participation in an IB, through partnering with a technically/financially strong company, or through favourable funding. Whereas individuals could further reduce their personal risks by entering a collective, the overall risks might increase due to the complexities of managing a collective organisation. Nevertheless, in practice the more powerful commercial partner is often able to transfer risk to the smallholders during the implementation of the IB. Lastly, benefits for individuals are limited and slow to materialise. Farm development requirements, non-involvement in the IB, and lack of commitment to skills development hamper the rewards for the individual beneficiaries. Overall, this impairs the local economic development impact that IBs might have, certainly in the short term. The most significant benefit seems to come from gaining market access for beneficiaries who (initially) are not able to operate independently. Conversely, the commercial partner is able to control the IB, prioritising the business aspect over the developmental facet of the partnership (Chamberlain & Anseeuw, Citation2018).

Considering the long time required for achieving beneficiary capacitation and positive cash flow, IBs might become more inclusive in the future, aligning the implementation scores to the institutional set-up scores. A longitudinal study of IBs seems to be necessary for gaining a better understanding of the empowerment process of the beneficiaries (Kirsten et al., Citation2016). Recommendations to increase the developmental and transformative impact of IBs are outlined in Chamberlain and Anseeuw (Citation2018).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Argyres, NS & Liebeskind, JP, 1999. Contractual commitments, bargaining power, and governance inseparability: incorporating history into transaction cost theory. Academy of Management Review 24(1), 49–63. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.1580440

- Arias, P et al., 2013. Smallholder integration in changing food markets. FAO, Rome.

- van Averbeke, W & Mohamed, S, 2006. Smallholder farming styles and development policy in South Africa: The case of Dzindi irrigation scheme. Agrekon 45(2), 136–57. doi:10.1080/03031853.2006.9523739.

- Baden, S, 2014. Collective action, gender relations and social inclusion in African agricultural markets. Policy brief 64. Future Agricultures Consortium, Brighton.

- Baumann, P, 2000. Equity and efficiency in contract farming schemes: The experience of agricultural tree crops. Working paper 139. Overseas Development Institute, London.

- BCtA, no date. Measuring value of Business Call to Action initiatives: A results reporting framework. BCtA, New York.

- Béné, C, 2003. When fishery rhymes with poverty: A first step beyond the old paradigm on poverty in small-scale fisheries. World Development 31(6), 949–75. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00045-7.

- Berdegué, JA, Biénabe, E & Peppelenbos, L, 2008. Innovative practice in connecting small-scale producers with dynamic markets. IIED, London.

- Bernard, T & Spielman, DJ, 2009. Reaching the rural poor through rural producer organizations? A study of agricultural marketing cooperatives in Ethiopia. Food Policy 34(1), 60–69. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.08.001.

- Bijman, J, 2008. Contract farming in developing countries. An overview. Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Binswanger-Mkhize, HP, 2014. From failure to success in South African land reform. African Journal of Agriculture and Resource Economics 9(4), 253–69.

- Birdsall, N & Londoño, JL, 1997. Asset inequality matters An assessment of the World Bank’s approach to poverty reduction. American Economic Review 87(2), 32–7.

- Carter, MR & Barrett, CB, 2006. The economics of poverty traps and persistent poverty: An asset-based approach. The Journal of Development Studies 42(2), 178–99. doi:10.1080/00220380500405261.

- Chamberlain, WO & Anseeuw, W, 2017a. Contract farming as part of a multi-instrument inclusive business structure: A theoretical analysis. Agrekon, Taylor & Francis 56(2), 158–72. doi:10.1080/03031853.2017.1297725.

- Chamberlain, WO & Anseeuw, W, 2017b. Inclusive businesses in agriculture. What, how and for whom? Critical insights based on South African cases. SUN MeDIA MeTRO, Stellenbosch.

- Chamberlain, WO & Anseeuw, W, 2018. Inclusive businesses and land reform: Corporatization or transformation? Land 7(1), 18 doi:10.3390/land7010018.

- Cheyns, E, 2014. Making ‘minority voices’ heard in transnational roundtables: The role of local NGOs in reintroducing justice and attachments. Agriculture and Human Values 31(3), 439–53. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9505-7.

- Cochet, H, Anseeuw, W & Fréguin-Gresh, S, 2015. South Africa’s agrarian question. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Deininger, K & Olinto, P, 2000. Asset distribution, inequality, and growth. Policy Research Working Paper 2375. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Dercon, S, 1998. Wealth, risk and activity choice: cattle in Western Tanzania. Journal of Development Economics 55(1), 1–42. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(97)00054-0

- Dercon, S, 2004. Growth and shocks: evidence from rural Ethiopia. Journal of Development Economics 74, 309–29. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.01.001.

- Dercon, S & Christiaensen, L, 2011. Consumption risk, technology adoption and poverty traps: evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Development Economics 96(2), 159–73. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.08.003.

- Fréguin-Gresh, S & Anseeuw, W, 2014. Integrating smallholders in the South African citrus sector. In da Silva, CA & Rankin, M (Eds.), Contract farming for inclusive market access. FAO, Rome, 79–104.

- Friedmann, J, 1992. Empowerment: The politics of alternative development. Blackwell, Oxford.

- Gradl, C et al., 2012. Growing business with smallholders. A guide to inclusive agribusiness. GIZ, Bonn.

- Hall, DC, Ehui, S & Delgado, C, 2004. The livestock revolution, food safety, and small-scale farmers: why they matter to us all. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 17, 425–44. doi: 10.1007/s10806-004-5183-6

- Hendrickson, MK et al., 2014. Choice and voice: creating a community of practice in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Agriculture and Human Values 31, 665–72. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9532-4.

- Inkpen, AC & Tsang, EWK, 2005. Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer. The Academy of Management Review 30(1), 146–65. doi: 10.5465/amr.2005.15281445

- James, HS & Sulemana I, 2014. Case studies on smallholder farmer voice: An introduction to a special symposium. Agriculture and Human Values 31(4), 637–41. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9554-y.

- Johnson, N et al., 2016. Gender, assets, and agricultural development: lessons from eight projects. World Development, Elsevier Ltd 83, 295–311. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.009.

- Kamanga, BCG et al., 2010. Risk analysis of maize-legume crop combinations with smallholder farmers varying in resource endowment in central Malawi. Experimental Agriculture 46(01), 1–21. doi:10.1017/S0014479709990469.

- Kirsten, J & Sartorius, K, 2002. Linking agribusiness and small-scale farmers in developing countries: is there a new role for contract farming? Development Southern Africa 19(4), 503–29. doi: 10.1080/0376835022000019428

- Kirsten, J et al., 2016. Performance of land reform projects in the North West province of South Africa: changes over time and possible causes. Development Southern Africa, Taylor & Francis 33(4), 442–58. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2016.1179104.

- de Koning, M & de Steenhuijsen Piters, B, 2009. Farmers as shareholders: A close look at recent experience. Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) (Bulletin), Amsterdam.

- Lahiff, E, Davis, N & Manenzhe, T, 2012. Joint ventures in agriculture: lessons from land reform projects in South Africa. IIED/IFAD/FAO/PLAAS, London/Rome/Cape Town.

- Meinzen-Dick, R et al., 2011. Gender, assets, and agricultural development programs: A conceptual framework. CAPRi Working paper 99. CAPRI, Washington, DC.

- Nelson, V & Tallontire, A, 2014. Battlefields of ideas: changing narratives and power dynamics in private standards in global agricultural value chains. Agriculture and Human Values 31(3), 481–97. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9512-8.

- Ortmann, GF & King, RP, 2007. Agricultural cooperatives I: History, theory and problems. Agrekon 46(1), 40–68. doi:10.1080/03031853.2007.9523760.

- Patt, A, Suarez, P & Hess, U, 2010. How do small-holder farmers understand insurance, and how much do they want it? Evidence from Africa. Global Environmental Change 20, 153–61. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.10.007.

- Sabates-Wheeler, R, 2008. Asset inequality and agricultural growth: How are patterns of asset inequality established and reproduced? In Bebbington, AJ et al. (Eds.), Institutional pathways to equity. The World Bank, Washington, DC, 45–72.

- da Silva, CA & Ranking, M, 2013. Contract farming for inclusive market access. FAO, Rome.

- Sivramkrishna, S & Jyotishi, A, 2008. Monopsonistic exploitation in contract farming: Articulating a strategy for grower cooperation. Journal of International Development 20, 280–96. doi:10.1002/jid.1411.

- Stringer, LC, Twyman, C & Gibbs, LM, 2008. Learning from the South: Common challenges and solutions for small-scale farming. The Geographical Journal 174(3), 235–50. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2008.00298.x.

- Terblanché, SE, 2011. Mentorship a key success factor in sustainable land reform projects in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 39, 55–74.

- Vermeulen, S & Cotula, L, 2010. Making the most of agricultural investment: A survey of business models that provide opportunities for smallholders. IIED/FAO/IFAD/SDC, London/Rome/Bern.

- Wach, E, 2012. Measuring the ‘inclusivity’ of inclusive business. IDS Practice Papers 2012 (9), 1–30. doi:10.1111/j.2040-0225.2012.00009_1.x doi: 10.1111/j.2040-0225.2012.00009_2.x